Abstract

The cytotoxic complex, [PtCl(Am)2(ACRAMTU)](NO3)2 (1) ((Am)2 = ethane-1,2-diamine, en; ACRAMTU = 1-[2-(acridin-9-ylamino)ethyl]-1,3-dimethylthiourea), is a dual platinating/intercalating DNA binder that, unlike clinical platinum agents, does not induce DNA cross-links. Here, we demonstrate that substitution of the thiourea with an amidine group leads to greatly enhanced cytotoxicity in H460 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in vitro and in vivo. Two complexes were synthesized: 4a (Am2 = en) and 4b (Am = NH3), in which N-[2-(acridin-9-ylamino)ethyl]-N-methylpropionamidine replaces ACRAMTU. Complex 4a proves to be a more efficient DNA binder than complex 1 and induces adducts in sequences not targeted by the prototype. Complexes 4a and 4b induce H460 cell kill with IC50 values of 28 and 26 nM, respectively, and 4b slows tumor growth in a H460 mouse xenograft study by 40% when administered at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg. Compound 4b is the first non-cross-linking platinum agent endowed with promising activity in NSCLC.

Introduction

The transition metal complex cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II), also known as cisplatin (Figure 1), and its second-generation derivatives have become the mainstay of life-prolonging treatment for many tumors.1 Despite the therapeutic success of cisplatin when administered alone or as a component of combination regimens, severe toxicities and cellular resistance limit the clinical utility of this drug.2 Resistance to platinum drugs, perhaps the most serious drawback, is multifactorial in nature, which complicates the design of compounds able to circumvent the underlying resistance mechanisms.2 While certain tumors tend to acquire resistance after treatment with platinum, other forms of the disease are inherently chemoresistant. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), for instance, a major cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, is notoriously insensitive to treatment with classical cytotoxic agents, including platinum-based drugs.3 Despite the poor clinical prognosis of the disease, dual-agent regimens containing cisplatin (or less toxic carboplatin) in combination with a non-platinum agent are currently the only treatment options for patients with advanced NSCLC.4, 5 This sobering fact demonstrates the urgent need for novel chemotypes to combat this aggressive form of cancer.

Figure 1.

Structures of cisplatin and the hybrid agent, PT-ACRAMTU (1).

It has now become a widely accepted notion that in order to overcome the problem of tumor resistance to platinum drugs it is necessary to design agents that damage DNA radically differently than the classical cross-linkers.6 The rationale behind this approach is that novel types of cytotoxic lesions may evade the cellular DNA repair machinery and/or trigger cancer cell death by alternate mechanisms at the genome level. Platinum–acridinylthiourea conjugates, represented by the prototype, [PtCl(en)(ACRAMTU-S)](NO3)2 (1) (“PT-ACRAMTU”; en = ethane-1,2-diamine, ACRAMTU = 1-[2-(acridin-9-ylamino)ethyl]-1,3-dimethylthiourea) (Figure 1), are a class of cationic DNA-targeted hybrid agents designed toward this goal.7 Unlike the clinical cross-linking agents, compound 1 damages DNA by a dual mechanism involving monofunctional platinum binding to guanine (80%) or adenine (20%, 5–10% of which are previously unknown minor-groove adducts), and intercalation of the acridine moiety into the base pair step adjacent to the site of platination.8–11 These adducts and the structural perturbations they produce in DNA do not mimic cisplatin’s.12, 13

Despite its charged nature and inability to induce DNA cross-links, two features violating the classical chemical requirements for antitumor activity in cisplatin-type complexes,14 compound 1 showed a strong cytotoxic effect in a broad range of solid tumors in vitro similar, or superior, to that of the clinical drug, particularly in NSCLC cell lines of different genetic backgrounds.7, 15 Unfortunately, the compound’s cytotoxicity did not translate into inhibition of tumor growth in vivo (unreported data). These findings prompted several structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies with the ultimate goal of generating an analogue endowed with clinically useful antitumor activity. Modifications were made to the linker geometry,15 the spectator ligands on the metal center,16 and the intercalating portion of the molecule.17 However, none of the derivatives showed a major advantage over compound 1 and some of the modifications compromised the compounds’ aqueous solubility. We now report the groundbreaking discovery of an intriguingly simple chemical modification that has a dramatic effect on the biocoordination chemistry and biological activity of this type of conjugate: the replacement of thiourea sulfur with amidine nitrogen as the donor atom connecting the metal and intercalator moieties. The newly designed compound is the first example of this type of hybrid agent able to slow progression of an aggressive form of cancer in vivo.

Results

Design and Synthesis

Because the modifications pursued previously did not have the desired effect, structurally less invasive ways of modulating the reactivity of platinum were explored. Of particular interest in this context were the consequences of replacing the sulfur atom in complex 1 with sp2 (imino) nitrogen. The goal was to design a compound containing a suitably modified acridine derivative, whose geometry would closely mimic that of ACRAMTU, which was accomplished by introducing an amidine group.

The desired acridine, N-[2-(acridin-9-ylamino)ethyl]-N-methylpropionamidine, was synthesized and introduced as a ligand in one step (Scheme 1) by addition of the secondary amino group in N-(acridin-9-yl)-N′-methylethane-1,2-diamine across the activated CN bond18 of platinum-bound propionitrile (EtCN). Amidination reactions were performed with the appropriate platinum precursors (3a, 3b) derived from complexes [PtCl2L2] (L2 = en, 2a; L = NH3, 2b) to afford the corresponding platinum–acridine hybrids, which were isolated in their fully protonated form as the water soluble dinitrate salts, 4a and 4b. The structure of 4a, as determined by X-ray crystallography, confirms the formation of the desired amidine coordinative linkage and overall complex geometry, which shows platinum in a square planar environment defined by a single chloro leaving group, a bidentate en non-leaving group, and amidine nitrogen (Figure 2). Crystal data and selected bond lengths and angles for complex 4a are summarized in Table S2 and Table S3. A comparison of the molecular structures of 4a and 1 reveals a critical difference between the amidine and thiourea coordination modes: while the bond angle at the donor atom (N1) in 4a is 129.6(4)°, the corresponding angle at sulfur in 1 is considerably more acute (103.8(4)°).19 The opening of this bond angle in 4a relieves steric hindrance in the coordination sphere of the metal, which has previously been identified as a rate-limiting factor in reactions of complex 1 with DNA nitrogen.19, 20

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Target Compoundsa

a Reagents and conditions: (i) EtCN/H2O, 70 °C, 2 h. (ii) 1. AgNO3, DMF, r.t.; 2. N-(acridin-9-yl)-N′-methylethane-1,2-diamine, DMF, −10 °C, 7 h; 3. HNO3, MeOH.

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of 4a with selected atoms labeled. Nitrate counter ions are not shown. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

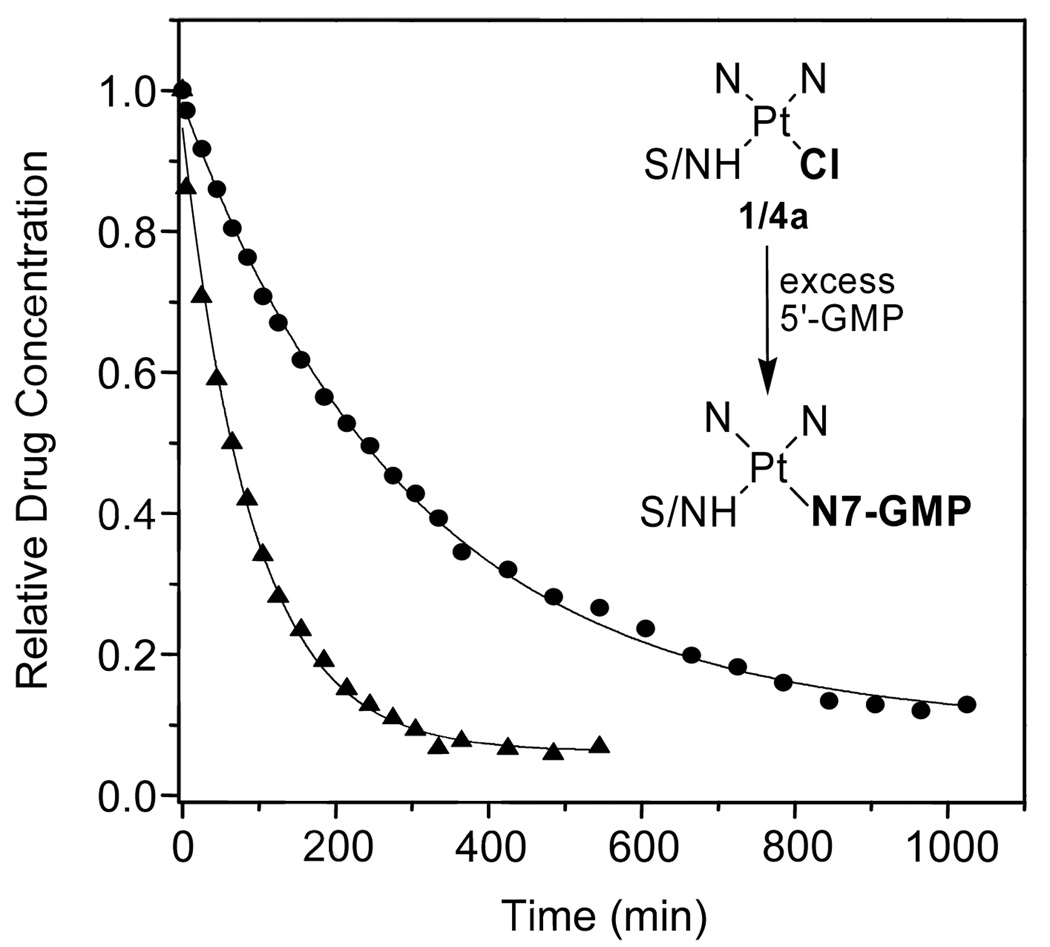

Kinetics of DNA Platination

To test the effect of the modification made to the prototypical agent on the metal’s reactivity with DNA, the reactions of 1 and 4a were initially monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy in a simple model system mimicking DNA nitrogen. Compound 4a reacts significantly faster with 5′-guanosine monophosphate (5′-GMP) than compound 1 (Figure 3 and Figure S1). From pseudo-first-order treatment of the kinetic data, rate constants (kobs, 37 °C) of 1.77 × 10−4 s−1 and 4.93 × 10−5 s−1 were calculated, which correspond to half lives of 65 min and 234 min for 4a and 1, respectively. Detailed analysis of the 1H NMR data indicates that compound 4a forms monoadducts, in which guanine-N7 has selectively substituted the chloro ligand, whereas the platinum–amidine linkage proves to be resistant to nucleophilic attack by nucleobase nitrogen in the presence of excess nucleotide, in complete analogy to complex 1.20,22 A 2-D [1H,15N] heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence (HMQC) NMR study performed with 15N-labeled complex (4a′) supports this mechanism and suggests that adduct formation is most likely preceded by aquation of the Pt–Cl bond, which is commonly observed in platinum drug–DNA interactions21 (Figure S2 and Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Progress of the reaction of 1 (circles) and 4a (triangles) with the mononucleotide 5′-GMP at 37 °C monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The inset shows a scheme of the reaction monitored. The data plotted is the mean of two experiments.

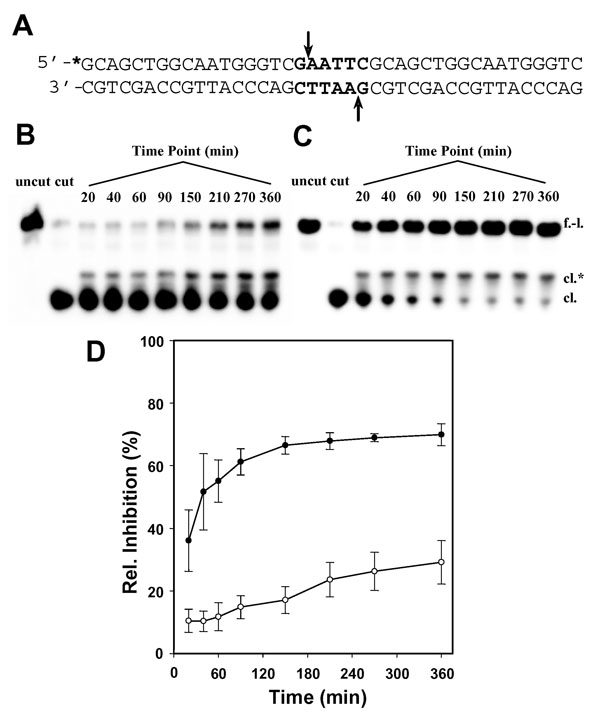

To compare the kinetics of DNA adduct formation by 1 and 4a in a biologically more relevant structural context, a restriction enzyme cleavage inhibition assay was developed. This assay takes advantage of the fact that adducts formed by complex 1 at an endonuclease’s restriction site inhibit enzymatic DNA strand scission.13 A 40-base-pair double-stranded DNA fragment (Figure 4(A)) was designed containing the central palindromic sequence, G↓AATTC, the recognition sequence of EcoRI, where the arrow marks the site of enzymatic cleavage. Cytosine (C) was chosen as the 5′ flanking base to produce the sequence 5′-CG, a previously established major target site of complex 1,13 which was also detected for complex 4a (vide infra). Briefly, this sequence was incubated with both platinum complexes, and the reactions were quenched at appropriate time intervals. Thiourea was used as the quenching reagent, because it rapidly replaces chloride on platinum, preventing the metal from further reacting with the probe sequence, without reversing existing monofunctional DNA adducts.13 Samples were then digested with EcoRI and the products separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and quantified densitometrically. Based on the relative band intensities calculated for the full-length probe and the cleaved fragment on the gels (Figure 4(B–D)), complex 4a protects the GpA phosphodiester linkage from endonucleolytic cleavage more efficiently than complex 1. In addition to the higher level of inhibition caused by 4a (70%) relative to 1 (30%), the new derivative shows rapid initial binding with an apparent half life of less than 20 min. While binding of 4a is virtually complete at the 2.5 h time point, 1 has not reached its maximum binding level after 6 h of incubation. The data also shows that platination of nucleobase nitrogen by 4a is considerably faster in double-stranded DNA than in 5′-GMP. This can be attributed to accumulation of platinum on the biopolymer, producing high effective concentrations of electrophile. For comparison, the first DNA binding step of cisplatin, the formation of monoadducts, proceeds with a half life of ~2 h, followed by closure to the bifunctional cytotoxic lesion on the same time scale.21

Fig. 4.

DNA binding efficiency of 1 and 4a monitored by a restriction enzyme cleavage inhibition assay. (A) Sequence of the 40-base-pair probe with the EcoRI restriction site highlighted. The asterisk denotes the radioactive label. (B,C) Denaturing polyacrylamide gels for the enzymatic digestion of DNA incubated for the indicated time intervals at a platinum-to-nucleotide ratio of 0.1 at 37 °C with 1 and 4a, respectively. The lanes labeled ‘uncut’ and ‘cut’ are controls for the undigested and digested unplatinated 40-mer, respectively. Bands are labeled ‘f.-l.’ for the full-length form and ‘cl.’ for the cleaved 18-nucleotide fragment. The band of intermediate mobility labeled ‘cl.*’, which disappears upon addition of NaCN to the mixture prior to electrophoretic separation (not shown), was assigned to platinum-modified cleaved product. (D) Time course of EcoRI inhibition as the result of DNA damage by 1 (open circles) and 4a (filled circles) based on relative integrated band intensities (arbitrary units) determined densitometrically for the full-length form. Plotted data represent the mean ± S.D. of three individual experiments for each complex.

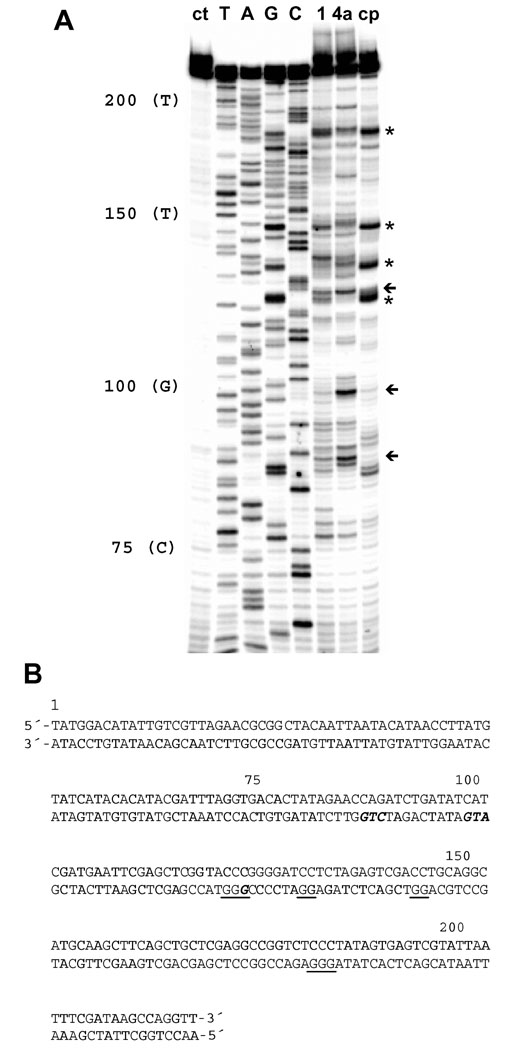

DNA adduct profile

In addition to the pronounced kinetic effect, substitution of the thiourea with an amidine group alters the DNA sequence specificity of platinum. A DNA polymerase inhibition assay coupled with PCR-amplified primer extension was used to detect differences in the irreversible damage produced by 1, 4a, and cisplatin. The phosphorimage of the footprinting gel is shown in Figure 5. In the 221-base-pair restriction fragment chosen as the template,16 cisplatin produces intense damage at (G)n sites (n ≥ 2), consistent with the formation of 1,2 GG intrastrand cross-links, the drug’s preferred binding mode.21 In contrast, complex 1 induces adducts with purine bases at the preferred intercalation sites of ACRAMTU.13 In the sequences 5′-CGGGT (bases 126–123) and 5′-TAGAGG (bases 137– 132), for instance, complex 1 produces stop sites at G or A of the pyrimidine/purine steps (underlined), but not in adjacent Gs. This is in agreement with a mechanism, in which the intercalating moiety dictates the sequence-specificity of platination, a hallmark of the DNA damage produced by complex 1.13 Likewise, 4a does not target cisplatin-specific sequences, however, the compound shows a damage profile distinct from that of complex 1. Complex 4a produces its most intense damage in the sequences 5′-CGG (bases 126–124), 5′-ATG (bases 102–100), and 5′-CTG (bases 90–88), where the apparent stop sites are underlined. The latter two damage sites are weak or virtually absent for complex 1 and cisplatin. Interestingly, DNA strand extension by Taq DNA polymerase in these two sequences appears to be terminated at T. This is atypical, since the stop sites in this assay are usually observed at the platinum-modified nucleobase (G or A). Although platination of thymine-N3 has been observed in mononucleotide models,23 this binding mode is unknown in biologically relevant DNA and seems an unlikely scenario adjacent to highly nucleophilic guanine-N7. Nevertheless, this binding mode cannot be completely ruled out and deserves further study.

Figure 5.

DNA polymerase inhibition assay for detection of DNA damage caused by 1, 4a, and cisplatin. (A) Phosphorimage of the sequencing gel showing inhibition of primer extension by Taq DNA polymerase resulting from platination of nucleobases. Lane assignments (from left to right): untreated damage control (ct); T, A, G, and C dideoxy sequencing lanes, giving the sequence on the platinum-modified template (bottom) strand, which reads 5′ to 3′ from top to bottom of the gel; lanes showing the PCR products resulting from Taq pol inhibition by adducts formed by 1, 4a, and cisplatin (cp) on the template strand. Asterisks and arrows indicate characteristic stop sites for cisplatin and complex 4a, respectively. (B) Sequence of the 221-base-pair restriction fragment with characteristic damage sites for cisplatin underlined and sequences targeted by complex 4a highlighted in bold, italicized letters.

Biological activity

The newly synthesized conjugates 4a and 4b were studied, along with the prototype, 1, for their cytotoxic effect in the human leukemia cell line, HL-60, and the NSCLC cell line, NCI-H460. The results of the cell proliferation assay are summarized in Table 1. In HL-60 cells, complex 4a showed moderate activity similar to 1, based on an IC50 value in the micromolar range. Complex 4b, in which the en nonleaving group was replaced with solubility-enhancing ammine ligands, was approximately 6-fold more potent in this cell line than 4a. All three compounds performed significantly better in H460 cells. This cell-line specific enhancement is most pronounced for compound 4a, which proves to be 100-fold more active in the solid tumor cell line than in the leukemia cell line. Most strikingly, complexes 4a and 4b were an order of magnitude more cytotoxic in H460 cells than complex 1. This is significant, since complex 1 has previously demonstrated only slightly better activity in this cell line than cisplatin (IC50 of 0.63 µM in clonogenic survival assays15).

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity Data

| IC50 (μM) ± SEMa | ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | HL-60 | NCI-H460 |

| 1 | 3.95 ± 0.24 | 0.35 ± 0.017 |

| 4a | 2.97 ± 0.11 | 0.028 ± 0.0024 |

| 4b | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.026 ± 0.0022 |

Concentrations of compound that reduce cell viability by 50%, determined by cell proliferation assays. Cells were incubated with platinum for 72 h. Values are means of four experiments ± the standard error of the mean.

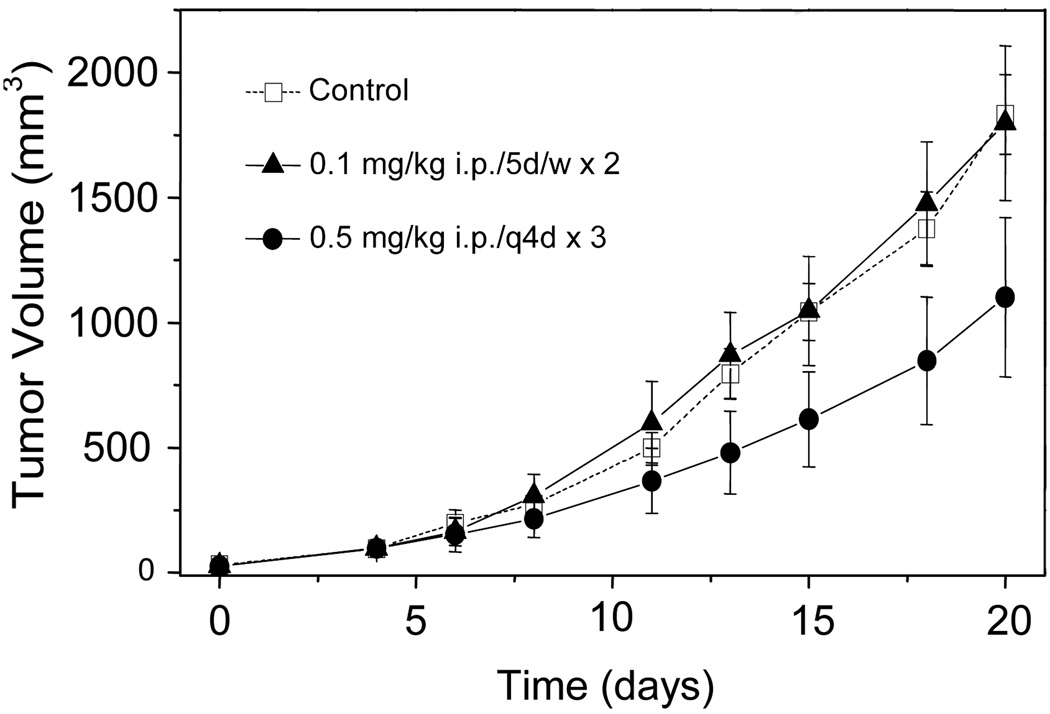

The antitumor activity of compound 4b was evaluated against H460 bilateral tumors implanted into athymic nude mice. Complex 4b was selected for this study, because it was slightly more soluble in biological media than 4a. Complex 4b was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) according to the following dosing schedules: (A) 0.1 mg/kg, five days per week for two consecutive weeks (5d/w×2), and (B) 0.5 mg/kg, three doses given at 4-day intervals (q4d×3). The tumor volumes recorded in both treatment groups and in untreated control animals are plotted vs. days of treatment in Figure 6. At the end of the study, the tumors measured 1834 ± 160, 1798 ± 309, and 1102 ± 319 mm3 (means ± S.E.M.) for the control animals and animals treated according to schedules A and B, respectively. Based on these data, the low-dose treatment (A) had no effect on tumor growth. However, treatment at the higher dose (B), which is close to the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of compound 4b, slowed the tumor growth rate significantly (P < 0.01) compared to the control group, which led to a reduction in the mean terminal tumor volume by 40%.

Figure 6.

Effect of 4b on H460 NSCLC tumors xenografted into nude mice. Growth curves are shown for untreated control animals (open squares), and mice treated according to schedule A (filled triangles) and schedule B (filled circles). Measurement of tumor volumes began on day 0, and treatment began on day 4. Each data point represents the mean of 5 tumor volumes ± S.E.M.

Discussion

PT-ACRAMTU (1) and its analogues were designed as DNA-targeted agents structurally and functionally different from cisplatin. Although complex 1 has a high noncovalent affinity for DNA (positive charge, intercalator), its reaction with nucleobase nitrogen proved to be relatively sluggish.20 Efficient formation of irreversible DNA adducts is one of the prerequisites for biological activity in these hybrid agents. Intercalation alone is only moderately cytotoxic, as demonstrated for both platinum-free intercalators and conjugates containing unreactive platinum moieties.16, 19 The goal was, therefore, to devise a chemical modification that would accelerate this crucial step without altering the pharmacophore’s previously optimized core structure. This was achieved by changing a sulfur donor in the metal coordination sphere into imino nitrogen.

The consequences of this chemical modification are manifest in a greatly enhanced DNA binding kinetics and an altered DNA damage profile compared to the prototype. While the exact mechanism and the associated rate laws are yet to be determined, amidine nitrogen appears to accelerate associative substitution reactions, most likely due to steric factors favoring nucleophilic attack on the metal. Hydrogen bonding between the imino hydrogen of the complex and exocyclic groups of the DNA bases, such as guanine-O6,21 may also contribute to the rate enhancement. Efficient DNA binding of the new derivatives is most likely a major contributor to the greatly improved biological activity in rapidly proliferating H460 cells. However, subtle structural differences at the target level that may render specific lesions induced by 4a and 4b more cytotoxic than those induced by 1 cannot be ruled out.

Complexes 4a and 4b are remarkably cytotoxic in H460 NSCLC cells. The only platinum-based agent known to inhibit H460 cell growth with similar potency in the nanomolar concentration range is BBR3464,24 a trinuclear platinum complex currently in clinical trials against various cancers. Cisplatin is at least 20-fold less potent than the non-classical agents in H460 cells with IC50 values typically in the micromolar range.15, 24 The high cell kill potential of the new hybrids in H460 cells translates into pronounced antitumor activity. This was demonstrated for compound 4b in the corresponding tumor xenograft, in which the agent slowed tumor growth at a sublethal dose close to the MTD. The high cytotoxic potency of compound 4b is documented by the fact that it is tolerated at doses an order of magnitude lower than those commonly applied for cisplatin when administered i.p.24 Because complex 4b is quite toxic at doses of 0.5 mg/kg, which results in significant weight loss in the test animals (Figure S4), further modifications of the new lead are necessary to minimize adverse effects and improve its therapeutic index. On the other hand, our new agent shows significantly improved cytotoxic potential compared to the ‘classical’ monofunctional, complex, cis-[Pt(NH3)2(pyridine)Cl]+, which requires high doses to produce an appreciable antitumor effect in vivo.25 A recent study in kidney cell lines demonstrates that relatively higher intracellular levels of this agent, mediated by organic cation transporters, are required to achieve a cytotoxic effect similar to that produced by the clinical agent, oxaliplatin.26

Non-cross-linking DNA-targeted agents, such as 4a and 4b, have great potential in the treatment of cancers insensitive to cisplatin because their adducts may evade DNA repair mechanisms. A growing body of evidence suggests that a correlation exists between the expression levels of nucleotide excision repair (NER) genes in NSCLC and progression of the disease: NSCLC patients with an excision repair-efficient tumor phenotype respond extremely poorly to platinum treatment.27–30 The NER pathway is responsible for the repair of platinum–DNA intrastrand cross-links, the putative cytotoxic lesions of cisplatin,31 which compromises the drug’s efficacy in affected cancers. NER recognizes and removes chemically irreversible bulky lesions that severely distort and destabilize duplex DNA.32 Unlike cisplatin’s major adduct, which severely bends DNA and reduces its thermal and thermodynamic stability,33 the monofunctional intercalative binding mode established for complex 1 (and also expected for 4a and 4b) causes local helix unwinding, but no bending, and increases the thermal stability of the modified duplex.9, 12 Therefore, the latter non-classical adducts may be poor substrates for NER and circumvent the associated resistance mechanism in affected cancer cells, which might explain why this type of hybrid agent performs better than cisplatin in NSCLC cells. Future biochemical assays will address this intriguing possibility.

In conclusion, the discovery of compounds 4a and 4b demonstrates the unique potential of metallodrugs in oncology. It shows how subtle tuning of the substitution chemistry of a transition metal can be exploited to enhance the biological activity of a DNA-targeted therapeutic agent. Platinum complexes like the newly designed agents that act by a mechanism at the DNA target level different from that of cisplatin and its analogues have great pharmacological potential. The new pharmacophore combines high target affinity and reactivity with the ability to induce cytotoxic lesions unknown for current clinical DNA-targeted agents, making it a promising candidate for the treatment of aggressive, chemoresistant cancer.

Experimental Section

Synthesis and Product Characterization

1H NMR spectra of the target compounds and intermediates were recorded on Bruker Advance 300 and DRX-500 instruments operating at 500 and 300 MHz, respectively. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advance 300 instrument operating 75.5 MHz. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in parts per million (ppm) relative to internal standards trimethylsilane (TMS), or 3-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propanesulfonic acid sodium salt (DSS) for samples in D2O. 195Pt NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX-500 MHz spectrometer at 107.5 MHz. Aqueous K2[PtCl4] was used as external standard, and 195Pt chemical shifts are reported vs [PtCl6]2−. The target compounds (4a and 4b) were fully characterized by gradient COSY and 1H-detected gradient HMQC and HMBC spectra recorded on a Bruker DRX-500 MHz spectrometer. Elemental analyses were performed by Quantitative Technologies Inc., Madison, NJ. All reagents were used as obtained from commercial sources without further purification unless indicated otherwise. Solvents were dried and distilled prior to use.

Synthesis of complex 3a

The complex [PtCl2(en)] (200 mg, 0.613 mmol) was heated under reflux in dilute HCl (pH 4) with propionitrile (2.7 mL, excess) until the yellow suspension turned into a colorless solution (~2 h). Solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the pale yellow residue was dissolved in 7 mL of dry methanol. The solution was passed through a syringe filter, and the colorless filtrate was added directly into 140 mL of vigorously stirred dry diethyl ether, affording 3a as an off-white microcrystalline precipitate, which was filtered off and dried in a vacuum. Yield 210 mg (90%). 1H NMR (D2O) δ 2.88 (2H, q, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.64 (4H, m), 1.30 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz). 13C-{H} NMR (D2O) δ 122.9, 48.7, 48.4, 12.3, 9.2. 195Pt NMR (D2O) δ–2711. Anal. (C5H13Cl2N3Pt) C, H, N.

Synthesis of complex 3b

This precursor was synthesized analogously to 3a starting from [PtCl2(NH3)2] (300 mg, 1 mmol) and propionitrile (4.2 mL). Yield: 295 mg (83%). 1H NMR (D2O) δ 2.89 (2H, q, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.31 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz). 13C-{H} NMR (D2O) δ 121.9, 12.3, 9.2. 195Pt NMR (D2O) δ-2467. Anal. (C3H11Cl2N3Pt) C, H, N.

Complexes 3a′ and 4a′ containing 15N-en were synthesized accordingly starting from [PtCl2(15N-en)]. 3a´: 1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 6.11 and 5.86 (2H, d of t, NH2 trans to Cl, 1J(1H–15N) = 75 Hz, 3J(1H–1H) = 5.3 Hz), 6.01 and 5.76 (2H, d of t, NH2 trans to N, 1J(1H–15N) = 75 Hz, 3J(1H–1H) = 5.2 Hz), 2.93 (2H, q, J = 7.6 Hz), 2.57 (4H, m), 1.33 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz). 4a´: 1H NMR (DMF-d7) δ 13.92 (1H, s), 9.90 (1H, s), 8.70 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 8.07 (4H, m, overlap), 7.63 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 6.26 (NH, 1H, s), 5.82 and 5.53 (2H, d of t, NH2 trans to Cl, 1J(1H–15N) = 74.5 Hz, 3J(1H–1H) = 5.0 Hz and 5.1 Hz), 5.47 (2H, d of t, NH2 trans to N, 1J(1H–15N) = 75 Hz, 3J(1H–1H) = 5.1 Hz), 4.51 (2H, t, J = 6.3 Hz), 4.10 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz), 3.21 (3H, s), 3.12 (2H, q, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.68 (4H, s), 1.33 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz).

Synthesis of Complex 4a

Precursor complex 3a (170 mg, 0.45 mmol) was converted to its nitrate salt by reaction with AgNO3 (75 mg, 0.44 mmol) in 10 mL of anhydrous DMF. AgCl was filtered off, and the filtrate was cooled to −10 °C. N-(acridin-9-yl)-N′-methylethane-1,2-diamine8 (117 mg, 0.47 mmol) was added to the solution, and the suspension was stirred until it turned into an orange-red solution (~7 h). The reaction mixture was added dropwise into 200 mL of cold dichloromethane, and the resulting yellow slurry was vigorously stirred for 30 min. The precipitate was recovered by membrane filtration, dried in a vacuum overnight, and dissolved in 40 mL of methanol containing 1 mol equiv of HNO3. After removal of the solvent by rotary evaporation, the crude product was recrystallized from hot ethanol, affording 4a as a microcrystalline solid. Yield 169 mg (52%). 1H NMR (DMF-d7) δ 13.92 (1H, s), 9.90 (1H, s), 8.70 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 8.07 (4H, overl m), 7.63 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.78 (2H, s), 5.48 (2H, s), 4.51 2H, t, J = 6.3 Hz), 4.10 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz), 3.21 (3H, s), 3.12 (2H, q, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.68 (4H, s), 1.33 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz). 13C-{H} NMR (DMF-d7) δ 170.4, 159.0, 140.6, 135.7, 128.2, 124.3, 119.4, 113.5, 50.1, 49.4, 49.2, 47.5, 28.0, 11.4. 195Pt NMR (DMF-d7) δ –2494. UV/Vis (H2O): λmax 413, ɛ = 10571. Anal. (C21H31ClN8O6Pt·H2O) C, H, N.

Synthesis of Complex 4b

This analogue was prepared as described for 4a starting from 293 mg (0.83 mmol) of 3b, 132 mg (0.79 mmol) of AgNO3, and 197 mg (0.79 mmol) of N-(acridin-9-yl)-N′-methylethane-1,2-diamine. Yield: 315 mg (57%). 1H NMR (DMF-d7) δ 13.93 (1H, s), 9.92 (1H, s), 8.68 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 8.03 (4H, overl m), 7.62 (t, J = 7.2 Hz), 6.27 (1H, s), 4.53 (3H, s), 4.49 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 4.16 (3H, s), 4.10 (2H, t, J = 6.3 Hz), 3.20 (3H, s), 3.15 (2H, q, J = 7.6 Hz), 1.33 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz). 13C-{H} NMR (DMF-d7) δ 170.3, 159.3, 140.8, 135.9, 126.5, 124.5, 119.6, 113.6, 50.8, 47.8, 28.3, 11.5. 195Pt NMR (DMF-d7) δ –2264. UV/Vis (H2O): λmax 413, ɛ = 9224. Anal. (C19H29ClN8O6Pt·2.5H2O) C, H, N.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectra in arrayed experiments were collected at 37 °C on a Bruker 500 DRX spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance broadband inverse probe and a variable temperature unit. Reactions were performed in 5-mm NMR tubes containing 2 mM complex and 6 mM 5′-GMP (10 mM phosphate buffer, D2O, pH* 6.8). The 1-D 1H kinetics experiments were carried out as a standard Bruker arrayed 2-D experiment using a variable-delay list. Incremented 1-D spectra were processed exactly the same, and suitable signals were integrated. Data were processed with XWINNMR 3.6 (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). The concentrations of platinum complex at each time point were deduced from relative peak intensities, averaged over multiple signals to account for differences in proton relaxation, and the data were fitted to the equation, y = A0 × e−x/t (where A0 = 1 and t−1 = kobs), using Origin 7 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Details of the 2-D HMQC experiments are described in the Supporting Information.

Restriction Enzyme Cleavage Assay

The top and bottom strands of the 40-base-pair DNA fragment were synthesized and HPLC-purified by IDT Inc. (Coralville, IA). The top strand was radioactively labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (EPICENTRE Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) prior to annealing with the complementary strand in reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl). Conjugates 1 and 4a were incubated with labeled probe at 37 °C at a platinum-to-nucleotide ratio of 0.1, and the samples withdrawn at various time points from the mixtures were treated with thiourea (5-fold the concentration of platinum) at 4 °C for 30 min. Unmodified and platinum-modified DNA samples were reacted with 60 units of EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) at 37 °C for 40 min in enzyme buffer provided by the vendor. Digested and undigested fragments were separated on polyacrylamide gels (12% acrylamide, 8 M urea) and quantified on a BioRad FX-Pro Plus phosphorimager (Hercules, CA) using the BioRad Quantity One software (version 4.4.1).

DNA Polymerase Inhibition Assay

The 221-base-pair NdeI/HpaI restriction fragment from plasmid pSP73 was generated by PCR amplification and purified according to a published protocol.16 Appropriate amounts of DNA (10 µg/50 µL) were incubated with complexes 1, 4a, and cisplatin at a platinum-to-nucleotide ratio of 0.0075 in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at 37 °C for 24 h. All other manipulations and experimental conditions of this assay were adopted from previously optimized protocols,16 including 5′ end-labeling of primer, PCR protocols for dideoxy sequencing and footprinting reactions using Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), and details of the gel electrophoresis and documentation.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity studies were carried out according to a standard protocol17 using the Celltiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Stock solutions of 1, 4a, and 4b were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and serially diluted with media prior to incubation with cancer cells. IC50 values were calculated from non-linear curve fits using a sigmoidal dose-response equation in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Xenograft Study

H460 xenografts were established in nude athymic female mice via bilateral subcutaneous injections. Treatment began when the average tumor volume was approximately 100 mm3. The tumor-bearing mice were randomized depending on tumor volume into three groups of five test animals each: one control group receiving vehicle only, one group treated at 0.1 mg/kg 5d/w×2 (A), and one group treated at 0.5 mg/kg q4d×3 (B). Animal weights and tumor volumes were measured and recorded for 17 days after the first dose was administered. Tumor volumes were determined using the formula: V (mm3) = d2 × D/2, where d and D are the shortest and longest dimension of the tumor, respectively, and are reported as the sum of both tumors for each test animal. At the end of the study, all animals were euthanized and disposed off according to Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). The study was performed by Washington Biotechnology Inc. (Simpsonville, MD), PHS-approved Animal Welfare Assurance, # A4912-01. Statistical analysis of the growth curves was done using a non-linear polynomial random-coefficient model in SAS Proc Mixed (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Supplementary Material

Analytical data and NMR spectra for the new compounds; selected bond lengths and angles and crystal data for 4a; time-dependent NMR spectra for the reactions of 1 and 4a with 5′-GMP; results of the [1H-15N] HMQC experiments, including experimental details; plot of mouse weights vs. treatment days for xenograft study of complex 4b. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. L. Douglas Case (Department of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University School of Medicine) for assistance with the statistical analysis of the in vivo data and Dr. Yongqing Wang and Dr. Sean O’Neill (Washington Biotechnology Inc.) for helpful discussions. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute through grant CA101880. We thank the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs and the Department of Chemistry of WFU for supporting the in vivo evaluation of compound 4b.

Abbreviations

- ACRAMTU

1-[2-(acridin-9-ylamino)ethyl]-1,3-dimethylthiourea)

- COSY

correlated spectroscopy

- HMBC

heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation

- HMQC

heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence

- MTD

maximum tolerated dose

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabik CA, Dolan ME. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and toxicity associated with platinating agents. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2007;33:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosaert J, Quoix E. Platinum drugs in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;87:825–833. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wakelee H, Dubey S, Gandara D. Optimal adjuvant therapy for non-small cell lung cancer--how to handle stage I disease. Oncologist. 2007;12:331–337. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-3-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soria JC, Le Chevalier T. Is cisplatin still the best platinum compound in non-small-cell lung cancer? Ann. Oncol. 2002;13:1515–1517. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Momekov G, Bakalova A, Karaivanova M. Novel approaches towards development of non-classical platinum-based antineoplastic agents: design of platinum complexes characterized by an alternative DNA-binding pattern and/or tumor-targeted cytotoxicity. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:2177–2191. doi: 10.2174/0929867054864877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guddneppanavar R, Bierbach U. Adenine-n3 in the DNA minor groove - an emerging target for platinum containing anticancer pharmacophores. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2007;7:125–138. doi: 10.2174/187152007779313991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martins ET, Baruah H, Kramarczyk J, Saluta G, Day CS, Kucera GL, Bierbach U. Design, synthesis, and biological activity of a novel non-cisplatin-type platinum-acridine pharmacophore. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:4492–4496. doi: 10.1021/jm010293m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baruah H, Rector CL, Monnier SM, Bierbach U. Mechanism of action of non-cisplatin type DNA-targeted platinum anticancer agents: DNA interactions of novel acridinylthioureas and their platinum conjugates. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry CG, Baruah H, Bierbach U. Unprecedented monofunctional metalation of adenine nucleobase in guanine- and thymine-containing dinucleotide sequences by a cytotoxic platinum-acridine hybrid agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9629–9637. doi: 10.1021/ja0351443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barry CG, Day CS, Bierbach U. Duplex-promoted platination of adenine-N3 in the minor groove of DNA: challenging a longstanding bioinorganic paradigm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1160–1169. doi: 10.1021/ja0451620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baruah H, Wright MW, Bierbach U. Solution structural study of a DNA duplex containing the guanine-N7 adduct formed by a cytotoxic platinum-acridine hybrid agent. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6059–6070. doi: 10.1021/bi050021b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budiman ME, Alexander RW, Bierbach U. Unique base-step recognition by a platinum-acridinylthiourea conjugate leads to a DNA damage profile complementary to that of the anticancer drug cisplatin. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8560–8567. doi: 10.1021/bi049415d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connors TA, Cleare MJ, Harrap KR. Structure-Activity-Relationships of the Anti-Tumor Platinum Coordination-Complexes. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1979;63:1499–1502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess SM, Mounce AM, Sequeira RC, Augustus TM, Ackley MC, Bierbach U. Platinum-acridinylthiourea conjugates show cell line-specific cytotoxic enhancement in H460 lung carcinoma cells compared to cisplatin. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005;56:337–343. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0987-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guddneppanavar R, Choudhury JR, Kheradi AR, Steen BD, Saluta G, Kucera GL, Day CS, Bierbach U. Effect of the diamine nonleaving group in platinum-acridinylthiourea conjugates on DNA damage and cytotoxicity. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2259–2263. doi: 10.1021/jm0614376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guddneppanavar R, Saluta G, Kucera GL, Bierbach U. Synthesis, biological activity, and DNA-damage profile of platinum-threading intercalator conjugates designed to target adenine. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:3204–3214. doi: 10.1021/jm060035v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kukushkin VY, Pombeiro AJ. Additions to metal-activated organonitriles. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1771–1802. doi: 10.1021/cr0103266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ackley MC, Barry CG, Mounce AM, Farmer MC, Springer BE, Day CS, Wright MW, Berners-Price SJ, Hess SM, Bierbach U. Structure-activity relationships in platinum-acridinylthiourea conjugates: effect of the thiourea nonleaving group on drug stability, nucleobase affinity, and in vitro cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2004;9:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guddneppanavar R, Wright MW, Tomsey AK, Bierbach U. Guanine binding of a cytotoxic platinum-acridin-9-ylthiourea conjugate monitored by 1-D 1H and 2-D [1H-15N] NMR spectroscopy: Hydrolysis is not the rate-determining step. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelasco A, Lippard SJ. Anticancer activity of cisplatin and related complexes. In: Clarke MJ, Sadler PJ, editors. Topics in Biological Inorganic Chemistry. Vol 1. New York: Springer; 1999. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baruah H, Day CS, Wright MW, Bierbach U. Metal-intercalator-mediated self-association and one-dimensional aggregation in the structure of the excised major DNA adduct of a platinum-acridine agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4492–4493. doi: 10.1021/ja038592j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margiotta N, Habtemariam A, Sadler PJ. Strong, rapid binding of a platinum complex to thymine and uracil under physiological conditions. Angew Chem Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:1185–1187. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manzotti C, Pratesi G, Menta E, Di Domenico R, Cavalletti E, Fiebig HH, Kelland LR, Farrell N, Polizzi D, Supino R, Pezzoni G, Zunino F. BBR 3464: A novel triplatinum complex, exhibiting a preclinical profile of antitumor efficacy different from cisplatin. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:2626–2634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollis LS, Amundsen AR, Stern EW. Chemical and Biological Properties of a New Series of Cis-Diammineplatinum(II) Antitumor Agents Containing 3 Nitrogen Donors - Cis-[Pt(NH3)2(N-Donor)Cl]+ J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:128–136. doi: 10.1021/jm00121a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovejoy KS, Todd RC, Zhang S, McCormick MS, D'Aquino JA, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Giacomini KM, Lippard SJ. cis-Diammine(pyridine)chloroplatinum(II), a monofunctional platinum(II) antitumor agent: Uptake, structure, function, and prospects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8902–8907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803441105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray J, Simon G, Bepler G. Molecular predictors of chemotherapy response in non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:545–549. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weaver DA, Crawford EL, Warner KA, Elkhairi F, Khuder SA, Willey JC. ABCC5, ERCC2, XPA and XRCC1 transcript abundance levels correlate with cisplatin chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Mol. Cancer. 2005;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujii T, Toyooka S, Ichimura K, Fujiwara Y, Hotta K, Soh J, Suehisa H, Kobayashi N, Aoe M, Yoshino T, Kiura K, Date H. ERCC1 protein expression predicts the response of cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;59:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soria JC. ERCC1-tailored chemotherapy in lung cancer: the first prospective randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:2648–2649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zamble DB, Mu D, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Lippard SJ. Repair of cisplatin–DNA adducts by the mammalian excision nuclease. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10004–10013. doi: 10.1021/bi960453+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dip R, Camenisch U, Naegeli H. Mechanisms of DNA damage recognition and strand discrimination in human nucleotide excision repair. DNA Repair. 2004;3:1409–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poklar N, Pilch DS, Lippard SJ, Redding EA, Dunham SU, Breslauer KJ. Influence of cisplatin intrastrand crosslinking on the conformation, thermal stability, and energetics of a 20-mer DNA duplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Analytical data and NMR spectra for the new compounds; selected bond lengths and angles and crystal data for 4a; time-dependent NMR spectra for the reactions of 1 and 4a with 5′-GMP; results of the [1H-15N] HMQC experiments, including experimental details; plot of mouse weights vs. treatment days for xenograft study of complex 4b. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.