Abstract

Different physiological adaptations for anoxia resistance have been described in the animal kingdom. These adaptations are particularly important in organs that are highly susceptible to energy deprivation such as the heart and brain. Among vertebrates, turtles are one of the species that are highly tolerant to anoxia. In mammals however, insults such as anoxia, ischemia and hypoglycemia, all cause major histopathological events to the brain. However, in mammals even ischemic or anoxic tolerance is found when a sublethal ischemic/anoxic insult is induced sometime before a lethal ischemic/anoxic insult is induced. This phenomenon is defined as ischemic preconditioning. Better understanding of the mechanisms inducing both anoxic tolerance in turtles or ischemic preconditioning in mammals may provide novel therapeutic interventions that may aide mammalian brain to resist the ravages of cerebral ischemia. In this review, we will summarize some of the mechanisms implemented in both models of tolerance, emphasizing physiological and biochemical similarities.

INTRODUCTION

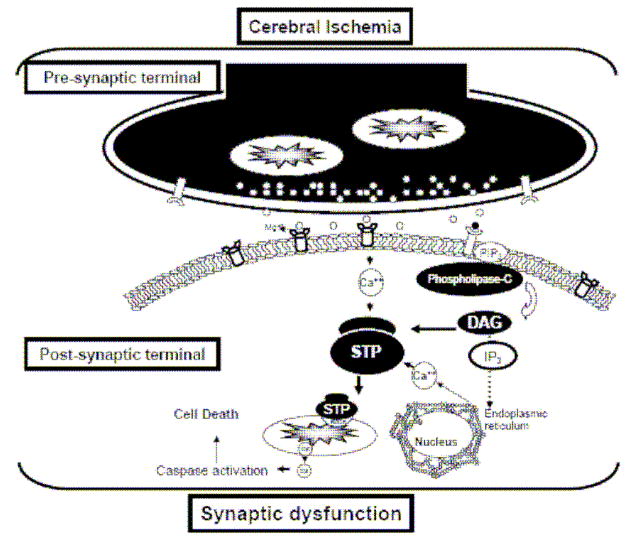

Different physiological adaptations for anoxia resistance have been described in the animal kingdom. These adaptations are particularly important in organs that are highly susceptible to energy deprivation such as the heart and brain. This vulnerability is especially evident in brain that, among body tissues, has the highest energy requirements and may be the most vulnerable to energy failure. It is well accepted that at least in mammals, brain is approx 3% of the body mass, yet it receives approx 15% of the total cardiac output and uses 20% of the body oxygen (Sokoloff 1989). In mammals, insults such as anoxia, ischemia and hypoglycemia, all cause the brain to become isoelectric within few minutes (Heiss et al. 1976; Astrup et al. 1977). If these insults are continued, the loss of electrical activity is followed by depletion of high energy intermediates, while lactate increases (Lowry et al. 1964), and by the loss of ion gradients (depolarization) (Hansen 1985). As ion gradients are lost, for example in ischemia, neurons release the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate which may amplify or cause irreversible pathologies during energy failure (Greenmayre 1986; Choi 1987) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a simplified cerebral ischemia induced cascade on synaptic dysfunction. Energy deprivation upon an ischemic insult promotes an exacerbated release of excitatory neurotransmitters that in turn overactivate glutamate receptors with a consequent cytosolic calcium overload that initiates aberrant signaling pathways that promote mitochondrial dysfunction and further synaptic dysfunction. DAG, diacylglycerol; STP, signal transduction pathway; Cyt c, cytochrome c.

Following these initial stages, the mechanisms leading to neuronal cell death after cerebral ischemia become more complex. A well established fact in this field is that cells continue to die over days and months after a stroke, a phenomenon that has been defined as delayed cell death. Although not clearly defined, neuronal cell death may result from either apoptosis, necrosis or a cell death mechanisms that is a mixture of these processes (Martin et al. 1998; Liou et al. 2003; Lo et al. 2003).

In addition numerous studies support the hypothesis that the reperfusion phase following cerebral ischemia contributes substantially to ischemic injury (Watson et al. 1989; Siesjo et al. 1991; Choi 1993; Chan 1994) and that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a central role (Abe et al. 1995; Ankarcrona et al. 1995; Schinder et al. 1996; White et al. 1996; White et al. 1997; Fiskum et al. 1999; Friberg et al. 2002).

In contrast to this susceptibility to energy deprivation in mammalian brain, the turtle brain is remarkably resistant to anoxia. Turtle brain survives anoxia by maintaining ATP levels necessary to avoid the loss of ion homeostasis and the uncontrolled release of excitotoxic neurotransmitters (Lutz et al. 2004; Nilsson et al. 2004). This delicate balance is achieved by increased glycolysis (Pasteur effect) and by decreasing energy demand.

Although mammalian brains are highly sensitive to loss of energy supply, as occurs during cerebral ischemia, in the last 20 years there has been a large number of studies demonstrating a unique mammalian brain adaptation that provide a metabolic state of resistance against cerebral ischemia, which is referred to as ischemic preconditioning (IPC). This state is reached when a brief (“sublethal”) ischemic episode, followed by a period of reperfusion, increase an organ’s resistance to injury (ischemic tolerance) following a subsequent ischemic event. This induction of tolerance against ischemia resulting from sublethal ischemic or anoxic insults has gained attention as a robust neuroprotective mechanism against conditions of stress such as anoxia/ischemia in heart and brain (Murry et al. 1986; Schurr et al. 1986; Kitagawa et al. 1990; Kato et al. 1992; Lin et al. 1992; Alkhulaifi et al. 1993; Lin et al. 1993; Walker et al. 1993; Perez-Pinzon et al. 1997c) and has the unique advantage over the non-vertebrate anoxia tolerance animal models in that it protects against ischemia, not just anoxia (see below). This is of particular importance in the field of stroke, because stroke remains the leading cause of disability and the third leading cause of death in USA and the Western world.

The present review examines similarities and differences among the mechanisms that promote both types of adaptations to anoxia in the turtle brain and to ischemia in the mammalian brain.

A key difference between anoxic and ischemic tolerance is that in the former, glucose is required. Thus, during cerebral anoxia in turtles, an enhanced glycolytic rate (Pasteur effect) is essential for the initial phases of tolerance. This is evident from studies demonstrating that inhibition of glycolysis with iodoacetic acid (IAA) (Sick et al. 1982b) or cerebral ischemia (Sick et al. 1985) or oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD) in vitro (as it would occur in ischemia) (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1992b) promote anoxic depolarization in turtle brains which although at a lower rate, then resemble the mammalian brain. In IPC, the Pasteur effect does not play a major role in ischemic resistance, since glucose is not available during cerebral ischemia.

A key factor required for both anoxic and ischemic tolerance is time. Turtle brains buy time by their intrinsic low metabolic rate, rapid inhibition of electrical activity and immediate increase in glycolytic rate upon anoxia. In mammalian ischemic tolerance, time is required after the induction of the sublethal insult before the right metabolic machinery is in place to promote tolerance against the lethal ischemic insult. This state of ischemic tolerance can now be achieved pharmacologically (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1996; Lange-Asschenfeldt et al. 2003; Raval et al. 2003; Raval et al. 2005).

Once ischemic tolerance is induced several mechanisms occur which are similar to anoxia tolerance in turtles. Thus, in this review we will focus on a) the common triggering mechanisms; and b) the two main sites where protection occurs (synaptic and mitochondrial sites).

a) Triggering mechanisms

a.1. Adenosine

Liu et al. (Liu et al. 1992) suggested that endogenous adenosine mediates IPC in cardiac muscle, since adenosine A1 receptor blockers eliminated the protective effect of IPC. Furthermore, acadesine (5-amino-4-imidazolecarboxamide riboside, AICAR), which increases local levels of adenosine delayed the natural decay of preconditioning (i.e., IPC protection was prolonged beyond 1 h) (Tsuchida et al. 1993; Tsuchida et al. 1994; Burckhartt et al. 1995). IPC was also enhanced by dipyridamole, which blocks adenosine uptake (Miura et al. 1992).

Recent evidence in brain also suggests that adenosine is involved in IPC (Figure 2). Supporting a role of adenosine also are findings that the nearly complete protection produced by IPC in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus 3 days after 6 min of global cerebral ischemia was abolished by DPCPX (1 mg/kg) (an adenosine A1 receptor antagonist). Infusion of cyclopentyl adenosine (CPA) (1 mg/kg) (an adenosine A1 receptor agonist) 15 min prior to ischemia, produced 70% protection of CA1 cells after 3 days of reperfusion (Heurteaux et al. 1995). We also demonstrated that both anoxic and ischemic preconditioning were neuroprotective via the adenosine A1 receptor in rat hippocampal brain slices (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1996; Lange-Asschenfeldt et al. 2003).

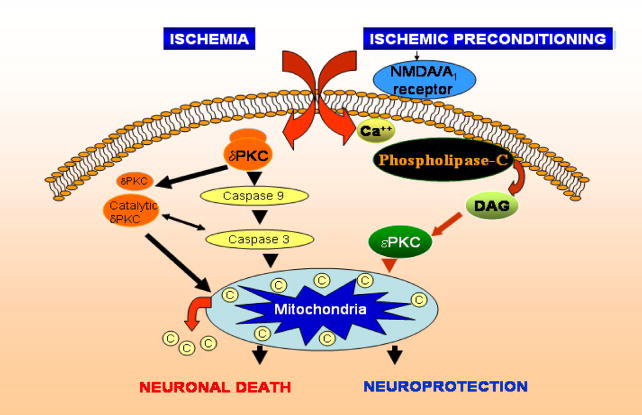

Figure 2.

Simplified scheme depicting the basic signaling pathways defined in ischemic preconditioning in mammals. Triggering pathways include activation of the NMDA and adenosine A1 receptors which in turn are involved in activating the epsilon isoform of protein kinase C. This pathway is known to protect mammalian neurons from excitotoxicity and against mitochondrial dysfunction.

In turtles, adenosine plays a critical role in anoxia tolerance in the early stages of the insult. Upon the induction of anoxia there is significant rise in extracellular adenosine levels in turtle brain (Nilsson et al. 1992), and blockade of the adenosine A1 receptors pharmacologically provokes anoxic depolarization in the turtle brain in vitro (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1993). This rise in extracellular adenosine levels provoke an increase in cerebral blood flow early in anoxia (Hylland et al. 1994), a reduction in membrane K+ leakage (Pek et al. 1997a), a reduction in glutamate efflux (Milton et al. 2002), and a down regulation in NMDA receptor activity and whole cell conductance (Buck et al. 1998).

a.2

Activation of the K+ATP channel, likely plays a role in at least some of the mechanisms of IPC. This is because blockade of the K+ATP channel abolished preconditioning and the protection afforded by adenosine and R-PIA (Schulz et al. 1994; Van Winkle et al. 1994). In contrast, a K+ATP channel opener (RP-52891, aprikalim) increased ischemic tolerance (Auchampach et al. 1992; Gross et al. 1992). Activation of K+ATP channel with bimakalin (agonist) during a preconditioning ischemic episode reduced the time necessary to produce preconditioning in dogs (Yao et al. 1994).

Recent evidence in brain also showed that transient infusion of K+ATP channel antagonist prior to ischemia can block IPC protection after forebrain ischemia (Heurteaux et al. 1995) or an agonist can emulate IPC in hippocampal slices (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1999a). However, the precise K+ATP channel involved remains undefined.

Recently, two ATP-sensitive potassium channels have been described. One of these channels resides in the plasma membrane; the other resides in the mitochondrial inner membrane. The mtK+ATP has been suggested to be the key channel involved in ischemic preconditioning, since the mtK+ATP blocker 5HD prevented IPC protection (Auchampach et al. 1992; Schultz et al. 1997). It has been hypothesized that opening of the mtK+ATP channel may depolarize mitochondrial membrane potential promoting an increase in the electron transport chain rate, and thus increasing ATP production (Inoue et al. 1991).

Because of the high bioenergetic component of ion pumping in brain, a reduction in ion permeability, often termed as “channel arrest”, has been proposed to be key for turtle brain survival during anoxia (Sick et al. 1982b; Lutz et al. 1985; Hochachka 1986). Much evidence supports this hypothesis and will be further described later in this review. However, K+ membrane conductances in turtle brain are believed to play a role in channel arrest. In an ingenious experiment, Chih et al. (Chih et al. 1989) tested whether there was a change in the rate of K+ leakage in normoxic vs anoxic turtle brains when the Na+-K+-ATPase pump was inhibited with ouabain. The rates of K+ leakage were significantly lower in brains subjected to 2 h of anoxia than in normoxic brains, supporting the suggestion that reduced ion leakage is an important mechanism for energy conservation during anoxia. These studies were followed by Pek and Lutz (Pek et al. 1997b), who determined that in the turtle cerebral cortex, intracellular to extracellular K+ flux is reduced by about 50% over the first hour of anoxia and plateaus at about 30% of the normoxic flux over the next few hours. Further, they determined that opened K+ATP channels and activated adenosine A1 receptors mediated this down-regulation of K+ flux.

b) Sites of protection

Numerous studies support the hypothesis that reperfusion following cerebral ischemia contributes substantially to ischemic injury (Watson et al. 1989; Siesjo et al. 1991; Choi 1993; Chan 1994) and that synaptic (Benveniste et al. 1989; Crepel et al. 1993) and mitochondrial dysfunction play a central role (Abe et al. 1995; Ankarcrona et al. 1995; Schinder et al. 1996; White et al. 1996; White et al. 1997; Fiskum et al. 1999; Friberg et al. 2002).

b.1: Synaptic protection

The link between synaptic dysfunction and brain ischemia is evident by the fact that about 50% of long-term survivors of cardiac arrest or transient ischemic attack exhibit impaired mental abilities, manifested as learning impairment, memory disturbance, concrete thinking, impaired attention and concentration, and reduced capacity to plan, initiate and carry out mental activities (Roine et al. 1993; Hankey 2003).

Cortical infarcts in focal cerebral ischemia models lead to an enhanced mode of synaptic plasticity, long term potentiation (LTP) in the area surrounding the ischemic core (Hagemann et al. 1998). In addition, previous studies demonstrated that GABAA receptor-mediated decreases in electrophysiological activities precede the morphologic deterioration in post-ischemic CA1 hippocampal neurons (Shinno et al. 1997). Seizures and altered synaptic plasticity (LTP) linked to cognitive deficits strongly suggest that alterations of synapses per se may be involved in these post-ischemic complications.

Finally, anoxic insults can elicit another form of LTP (Hsu et al. 1997). Anoxic LTP involves post-ischemic over-activation of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic responses (Kawai et al. 1998). Since it has been postulated that over-activation of NMDA receptors may promote cell death, it was proposed that this type of synaptic derangement was key in delayed neuronal death (Kawai et al. 1998).

Excitotoxicity

Many groups have demonstrated that IPC promotes tolerance by ameliorating different aspects of neuronal excitotoxicity. For example, glutamate release during ischemia was ameliorated by cortical spreading depression (CSD) (Douen et al. 2000) and by hypoxia/hypoglycaemia (Johns et al. 2000) preconditioning. Decreases in glutamate release was accompanied by increases in GABA release, which is suggested to be neuroprotective (Johns et al. 2000), and linked to down-regulation of the glial glutamate transporter isoforms EAAT2 and EAAT1 (Douen et al. 2000). IPC also promoted an increase in GABA release and upregulation of GABAA receptors in the hippocampus (Sommer et al. 2002).

In a recent study, we found that IPC promoted a robust release of GABA in rats after lethal ischemia compared with controls (Dave et al. 2005). We also observed that the activity of glutamate decarboxylase (the predominant pathway of GABA synthesis in the brain) was higher in the IPC group compared with control and ischemic groups. Because GABAA receptor up-regulation has been shown to occur following IPC, and GABAA receptor activation has been implicated in neuroprotection against ischemic insults, we further tested the hypothesis that GABAA or GABAB receptor activation was neuroprotective during ischemia or early reperfusion by using an in vitro model (organotypic hippocampal slice culture). Only administration of the GABAB agonist baclofen during test ischemia and for 1 h of reperfusion provided significant neuroprotection, but not the GABAA agonist. We concluded that increased GABA release in preconditioned rats after ischemia might be one of the factors responsible for IPC neuroprotection and that GABAB receptor may be the GABA receptor activated after IPC.

IPC-induced neuroprotection also appears to involve changes at the postsynaptic level. For example, IPC induced a small, transient down-regulation of GluR2 mRNA expression and greatly attenuated subsequent ischemia-induced GluR2 mRNA and protein down-regulation and neuronal death (which would promote AMPA receptors to be calcium permeable) (Tanaka et al. 2002). In addition, IPC was able to inhibit the induction of anoxic LTP in hippocampal slices (Kawai et al. 1998). These results suggested that protection by IPC may involve inhibition of postischemic overactivation of NMDA receptors.

In contrast to mammals, the turtle brain limits the exacerbated increases in excitatory neurotransmitters during anoxia (Nilsson et al. 1991; Milton et al. 1998). This decrease in excitatory neurotransmitter release may be due to the effect of channel arrest. As described above, changes in K+ conductances (Pek et al. 1997b) may play a role in the electrical activity depression observed in turtle brain during anoxia (Feng et al. 1988a; Feng et al. 1988b; Perez-Pinzon et al. 1991). Another explanation for this depression of electrical activity is that there is a 40% decrease in the density of voltage gated Na+ channels in the anoxic turtle cerebellum in vitro (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1992c) which correlated to an elevation in the action potential threshold (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1992a).

Another mechanism by which the turtle brain may reduce energy expenditure during anoxia is by releasing more of the inhibitory neurotransmitters. For example, extracellular GABA is elevated at approx 2 hours of anoxic exposure (Nilsson et al. 1991). In addition, there is an increase in GABAA receptor density, that continues to increase for at least 24 hours (Lutz et al. 1995). These changes in extracellular neurotransmitter levels are accompanied by a reduction in the NMDA glutamate receptor activity in the anoxic turtle brain (Bickler et al. 2000).

b.2: Mitochondrial dysfunction

In recent years a specific cellular site, namely mitochondria, has received special attention as a key player in cell death pathways (Fiskum et al. 1999; Murphy et al. 1999; Liou et al. 2003). This is evidenced by numerous studies that support the hypothesis that reperfusion following cerebral ischemia contributes substantially to ischemic injury (Watson et al. 1989; Siesjo et al. 1991; Choi 1993; Chan 1994) and that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a central role (Abe et al. 1995; Ankarcrona et al. 1995; Schinder et al. 1996; White et al. 1996; White et al. 1997; Fiskum et al. 1999; Friberg et al. 2002).

For example, following cerebral ischemia, a prominent change in redox activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain components has been observed (Welsh et al. 1982; Welsh et al. 1991; Rosenthal et al. 1995; Perez-Pinzon et al. 1997a; Perez-Pinzon et al. 1997b; Rosenthal et al. 1997). Previous studies suggested that this hyper-oxidation may result from loss of electron carriers from mitochondria following cerebral ischemia, such as cytochrome c (Perez-Pinzon et al. 1999b). The loss of cytochrome c from mitochondria might affect respiratory chain activity and/or trigger the apoptotic cascade (Nitatori et al. 1995; Charriaut-Marlangue et al. 1996). The release of cytochrome c has been linked to apoptosis (Ankarcrona et al. 1995; Schinder et al. 1996; Kluck et al. 1997; Yang et al. 1997).

Mitochondria isolated from ischemic brain exhibited decreases in “state 3” respiratory rates of approximately 70% with NAD-linked respiratory substrates (Sciamanna et al. 1992). Cafe et al. (Cafe et al. 1994) showed that non-synaptosomal mitochondria were insensitive to ischemia itself; however, mitochondria became dysfunctional in the late reperfusion phase. Mitochondria from synaptic terminals were greatly affected by ischemia, but partially recovered during reperfusion. Sims and Pulsinelli (Sims et al. 1987) also reported that the rate of oxygen consumption decreased in the CA1, CA3 and CA4 regions in the late reperfusion phase. Mitochondrial dysfunctions are reported in core and penumbra regions after MCAO (Kuroda et al. 1996; Anderson et al. 1999). Isolated mitochondria exhibited decrease in ADP stimulated respiration during early reperfusion period (Kuroda et al. 1996). However, activities of mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) complex I, II–III, and IV were preserved in penumbra as well as in the core region during early reperfusion following MCAO (Canevari et al. 1997). During late reperfusion phase following MCAO, the activity of mitochondrial ETC complex I is decreased (Davis et al. 1997). In summary, there are two phases of mitochondrial dysfunctions. In the first phase (early reperfusion), mitochondrial dysfunctions are mild (decreased activity of complex IV). However, in the second phase (late reperfusion), mitochondrial dysfunction is more pronounced.

IPC significantly protected against delayed cell death, and this protection was correlated with mitochondrial protection against the deficits in respiration affecting complexes I – IV (Dave et al. 2001; Perez-Pinzon et al. 2002). As described above, many studies have demonstrated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the resulting oxidative stress play a pivotal role in neuronal cell death (Flamm et al. 1978; Fridovich 1979; Siesjo et al. 1985; Kontos 1989; Vlessis et al. 1990; Hall et al. 1993). There are two major regions in the electron transport chain where ROS are produced. One is complex I and the other is complex III (Chance et al. 1956). Since oxidative stress is implicated in the pathophysiology that ensues after cerebral and cardiac ischemia (Kannan et al. 2000), one can surmise that a key mechanism by which IPC protects hippocampus against delayed neuronal cell death is by protecting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, diminishing ROS production and by limiting pro-apoptotic molecules to be released from mitochondria. In fact, all three mechanisms have been observed to occur in different models of IPC. The first one was demonstrated by our group (described above) (Dave et al. 2001; Perez-Pinzon et al. 2002). In addition, hypoxic preconditioning 24 h prior to OGD significantly reduced cell death from 83% to 22% in the necrotic model and 68% to 11% in the IPC model (Arthur et al. 2004). In this IPC model, the activity of the antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, and Mn superoxide dismutase were significantly increased. Furthermore, superoxide and hydrogen peroxide concentrations following OGD were significantly lower in the IPC group. Finally, cytochrome c release from mitochondria to the cytosol was suppressed in the ischemia-tolerance-induced hippocampal CA1 region (Nakatsuka et al. 2000).

Despite the important role of mitochondria in cell death pathways, not much has been done in the turtle brain during anoxic conditions. In turtle brain, cytochrome aa3 appeared more reduced than rat cytochrome aa3 in normoxia, which may be due either to lower affinity for O2 or to enhanced substrate supply (Sick et al. 1982a). These results were suggestive that the resistance to anoxia observed in turtles is likely due to differences in redox activities of cytochrome aa3 and/or in substrate use play a role in the relative insensitivity of turtle brain to O2 deprivation (Sick et al. 1982a). In turtle heart, Cai and Storey (Cai et al. 1996) reported the upregulation of mitochondrial genes for NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 5 and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 after prolonged anoxia in turtles, which, if translated into protein levels, would suggest increase efficiency of the electron transport chain of mitochondria and may render brain mitochondria resistant to ‘lethal’ ischemia.

Conclusions

There are some similarities in some of the neuroprotective strategies involved in both anoxic tolerance in turtle brain and ischemic tolerance in mammalian brain. For example, adenosine release and activation of adenosine receptors have been proven to play a role in both models of tolerance.

Although electrical activity depression and “channel arrest” are well established as a strategy for tolerance in turtle brains during anoxia, it is not clear in ischemic preconditioning in mammals. However, both types of tolerance attempt to shift excitotoxicity by limiting glutamate release and enhancing GABA release. This strategy appears well established in turtle brain, but in ischemic tolerance in mammals remain controversial.

Finally, much evidence suggests that IPC targets brain mitochondria as a site for neuroprotection given the fact that this organelle is highly sensitive to cerebral ischemia and that it can elicit the apoptotic pathway during the reperfusion phase. Turtle brain mitochondria in turn, may be spared from anoxic stress by enhancing the glycolytic capacity and better maintenance of ion homeostasis.

Although the turtle brain is a remarkable model of anoxic tolerance, the fact that it does not resist ischemic insults suggests that it is a good model for the development of novel therapeutic interventions in hypoxic/anoxic pathologies, but not in stroke. Ischemic preconditioning is better suited for the development of therapies against stroke. Finally, a new ischemic tolerance model that has recently emerged is the arctic ground squirrel. We recently demonstrated that these species’ brain is able to survive a clinically relevant model of ischemia, cardiac arrest (Dave et al. 2006). This finding is even more remarkable because brain ischemic resistance was found in euthermic conditions.

Peter L. Lutz

Peter was my mentor in graduate school and continued to mentor me as I continued my professional academic career. To me Peter was the old fashion scientist, more interested in understanding globally how the world works. I think he really disliked the super specialization of science, but to survive, he managed to keep up. Sadly, today’s scientific environment is not conducive for this approach to science.

Peter’s interests were not limited to science as every time I would meet him outside the laboratory enclaves (most likely at a bar/pub!) the conversations began with science, but ended up in politics, philosophy or religion. These were lively conversations/arguments and highly stimulating and motivated me to go home with the need to read few books before I met him again to continue our arguments. And this is how he faced science, with the same fervor and enthusiasm, with the same skepticism and always trying to connect the dots, even when they seemed impossible to connect! Speculation was his nature. He did not mind to be wrong or that you cannot publish speculative ideas, but he loved to speculate. It was part of his vivid imagination and curiosity. I surely miss Peter and Peter’s personality.

I surely miss his friendship! But he will remain a part of me.

Figure 3.

My mentor and friend, Dr. Peter L. Lutz in Edinburgh, Scotland during my first scientific conference in Europe.

Abbreviations

- IPC

ischemic preconditioning

- OGD

oxygen-glucose deprivation

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- CSD

cortical spreading depression

- MCAo

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- ETC

electron transport chain

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- IAA

iodoacetic acid

- CPA

cyclopentyl adenosine

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abe K, Aoki M, Kawagoe J, Yoshida T, Hattori A, Kogure K, Itoyama Y. Ischemic delayed neuronal death: A mitochondrial hypothesis. Stroke. 1995;26:1478–1489. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.8.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhulaifi AM, Pugsley WB, Yellon DM. The influence of the time period between preconditioning ischemia and prolonged ischemia on myocardial protection. Cardioscience. 1993;4:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MF, Sims NR. Mitochondrial respiratory function and cell death in focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1189–1199. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankarcrona M, Dypbukt JM, Bonfoco E, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Lipton SA, Nicotera P. Glutamate-induced neuronal death: A succession of necrosis or apoptosis depending on mitochondrial function. Neuron. 1995;15:961–973. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur PG, Lim SC, Meloni BP, Munns SE, Chan A, Knuckey NW. The protective effect of hypoxic preconditioning on cortical neuronal cultures is associated with increases in the activity of several antioxidant enzymes. Brain Res. 2004;1017:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrup J, Symon L, Branston NM, Lassen NA. Cortical evoked potential and extracellular K+ and H+ at critical levels of brain ischemia. Stroke. 1977;8:51–57. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchampach JA, Grover GJ, Gross GJ. Blockade of ischemic preconditioning in dogs by the novel ATP dependent potassium channel antagonist sodium 5-hydorxydecanoate. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:1054–1062. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste H, Jorgensen MB, Sandberg M, Christensen T, Hagberg H, Diemer NH. Ischemic damage in hippocampal CA1 is dependent on glutamate release and intact innervation from CA3. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:629–639. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickler PE, Donohoe PH, Buck LT. Hypoxia-induced silencing of NMDA receptors in turtle neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3522–3528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03522.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck LT, Bickler PE. Adenosine and anoxia reduce N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor open probability in turtle cerebrocortex. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:289–297. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckhartt B, Yang XM, Tsuchida A, Mullane KM, Downey JM, Cohen MV. Acadesine extends the window of protection afforded by ischaemic preconditioning in conscious rabbits. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29:653–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafe C, Torri C, Gatti S, Adinolfi D, Gaetani P, Rodriguez YBR, Marzatico F. Changes in non-synaptosomal and synaptosomal mitochondrial membrane-linked enzymatic activities after transient cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Res. 1994;19:1551–1555. doi: 10.1007/BF00969005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, Storey KB. Anoxia-induced gene expression in turtle heart. Upregulation of mitochondrial genes for NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 5 and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0083t.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canevari L, Kuroda S, Bates TE, Clark JB, Siesjo BK. Activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes after transient focal ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1166–1169. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199711000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PH. Oxygen radicals in focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Pathol. 1994;4:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1994.tb00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Williams G. The respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation. Adv Enzymol. 1956;17:65–134. doi: 10.1002/9780470122624.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charriaut-Marlangue C, Margaill I, Represa A, Popovivi T, Plotkine M, Ben-Ari Y. Apoptosis and necrosis after reversible focal ischemia: an in situ DNA fragmentation analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol. 1996;16:186–194. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih CP, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Ion leakage is reduced during anoxia in turtle brain: a potential survival strategy. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R1562–1564. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.6.R1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BH. Oxygen, antioxidants and brain dysfunction. Yonsei Med J. 1993;34:1–10. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1993.34.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Ionic dependence of glutamate neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1987;7:369–379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00369.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepel V, Hammond C, Krnjevic K, Chinestra P, Ben-Ari Y. Anoxia-induced LTP of isolated NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic responses. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1774–1778. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave KR, Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Raval AP, Prado R, Busto R, Saul I, Perez-Pinzon MA. Ischemic preconditioning ameliorates excitotoxicity by shifting glutamate/gamma-aminobutyric acid release and biosynthesis. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:665–673. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave KR, Prado R, Raval AP, Drew KL, Perez-Pinzon MA. The arctic ground squirrel brain is resistant to injury from cardiac arrest during euthermia. Stroke. 2006;37:1261–1265. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217409.60731.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave KR, Saul I, Busto R, Ginsberg MD, Sick TJ, Perez-Pinzon MA. Ischemic preconditioning preserves mitochondrial function after global cerebral ischemia in rat hippocampus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1401–1410. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Whitely T, Turnbull DM, Mendelow AD. Selective impairments of mitochondrial respiratory chain activity during aging and ischemic brain damage. Acta Neurochir. 1997;Suppl 70:56–58. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6837-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douen AG, Akiyama K, Hogan MJ, Wang F, Dong L, Chow AK, Hakim A. Preconditioning with cortical spreading depression decreases intraischemic cerebral glutamate levels and down-regulates excitatory amino acid transporters EAAT1 and EAAT2 from rat cerebal cortex plasma membranes. J Neurochem. 2000;75:812–818. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng ZC, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Suppression of evoked potentials with continued ion transport during anoxia in turtle brain. Am J Physiol. 1988a;255:R478–484. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.3.R478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng ZC, Sick TJ, Rosenthal M. Orthodromic field potentials and recurrent inhibition during anoxia in turtle brain. Am J Physiol. 1988b;255:R485–491. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.3.R485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskum G, Murphy AN, Beal MF. Mitochondria in neurodegeneration: acute ischemia and chronic neurodegenerative diseases. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:351–369. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamm ES, Demopoulos HB, Seligman ML, Poser RG, Ransohoff J. Free radicals in cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1978;9:445–447. doi: 10.1161/01.str.9.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg H, Wieloch T. Mitochondrial permeability transition in acute neurodegeneration. Biochimie. 2002;84:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Hypoxia and oxygen toxicity. Adv Neurol. 1979;26:255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenamyre JT. The role of glutamate in neurotransmission and in neurologic disease. Arch neurol. 1986;43:1058–1063. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520100062016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GJ, Auchampach JA. Blockade of ATP-sensitive potassium channels prevents myocardial preconditioning in dogs. Circ Res. 1992;70:223–233. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann G, Redecker C, Neumann-Haefelin T, Freund HJ, Witte OW. Increased long-term potentiation in the surround of experimentally induced focal cortical infarction. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:255–258. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ED, Braughler JM. Free radicals in CNS injury. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;71:81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankey GJ. Long-term outcome after ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16 Suppl 1:14–19. doi: 10.1159/000069936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AJ. Effect of anoxia on ion distribution in the brain. Physiol Rev. 1985;65:101–148. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1985.65.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss WD, Hayakawa T, Waltz AG. Cortical neuronal function during ischemia. Effects of occlusion of one middle cerebral artery on single-unit activity in cats. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:813–820. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500120017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurteaux C, Lauritzen I, Widmann C, Lazdunski M. Essential role of adenosine, adenosine A1 receptors, and ATP-sensitive K+ channels in cerebral ischemic preconditioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4666–4670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW. Defense strategies against hypoxia and hypothermia. Science. 1986;231:234–241. doi: 10.1126/science.2417316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KS, Huang CC. Characterization of the anoxia-induced long-term synaptic potentiation in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:671–681. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylland P, Nilsson GE, Lutz PL. Time course of anoxia-induced increase in cerebral blood flow rate in turtles: evidence for a role of adenosine. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:877–881. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue I, Nagase H, Kishi K, Higuti T. ATP-sensitive K channel mitochondrial inner membrane. Nature. 1991;352:244–247. doi: 10.1038/352244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns L, Sinclair AJ, Davies JA. Hypoxia/hypoglycemia-induced amino acid release is decreased in vitro by preconditioning. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:134–136. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan K, Jain SK. Oxidative stress and apoptosis. Pathophysiology. 2000;7:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4680(00)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Araki T, Murase K, Kogure K. Induction of tolerance to ischemia: alterations in second-messenger systems in the gerbil hippocampus. Brain Res Bull. 1992;29:559–565. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90123-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Nakagomi T, Kirino T, Tamura A, Kawai N. Preconditioning in vivo ischemia inhibits anoxic long-term potentiation and functionally protects CA1 neurons in the gerbil. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:288–296. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa K, Matsumoto M, Tagaya M, Hata R, Ueda H, Niinobe M, Handa N, Fukunaga R, Kimura K, Mikoshiba K, et al. ‘Ischemic tolerance’ phenomenon found in the brain. Brain Res. 1990;528:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90189-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluck RM, Bossywetzel E, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: A primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275:1132–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos HA. Oxygen radicals in CNS damage. Chem Biol Interact. 1989;72:229–255. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda S, Katsura K, Hillered L, Bates TE, Siesjo BK. Delayed treatment with alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butyl nitrone (PBN) attenuates secondary mitochondrial dysfunction after transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neurobiol Disease. 1996;3:149–157. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1996.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Raval A, Dave K, Pérez-Pinzón M. Adenosine-induced ischemic preconditioning neuroprotection requires activation of epsilonPKC isozyme in the organotypic hippocampal slice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:264. [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Dietrich WD, Ginsberg MD, Globus MY, Busto R. MK–801 (dizocilpine) protects the brain from repeated normothermic global ischemic insults in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:925–932. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Globus MY, Dietrich WD, Busto R, Martinez E, Ginsberg MD. Differing neurochemical and morphological sequelae of global ischemia: comparison of single- and multiple-insult paradigms. J Neurochem. 1992;59:2213–2223. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou AK, Clark RS, Henshall DC, Yin XM, Chen J. To die or not to die for neurons in ischemia, traumatic brain injury and epilepsy: a review on the stress-activated signaling pathways and apoptotic pathways. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:103–142. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Downey JM. Ischemic preconditioning protects against infarction in rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1107–1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo EH, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:399–415. doi: 10.1038/nrn1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O, Passonneau J, Hassels-Berger J, Schultz D. Effect of ischemia on known subtrates and co-factors of the glycolytic pathway in brain. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:18–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz P, Rosenthal M, Sick T. Living without oxygen: Turtle brain as a model of anaerobic metabolism. Mol Physiol. 1985;8:411–425. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz PL, Leone-Kabler SL. Upregulation of the GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor during anoxia in the freshwater turtle brain. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R1332–1335. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.5.R1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz PL, Nilsson GE. Vertebrate brains at the pilot light. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;141:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Al-Abdulla NA, Brambrink AM, Kirsch JR, Sieber FE, Portera-Cailliau C. Neurodegeneration in excitotoxicity, global cerebral ischemia, and target deprivation: A perspective on the contributions of apoptosis and necrosis. Brain Res Bull. 1998;46:281–309. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton SL, Lutz PL. Low extracellular dopamine levels are maintained in the anoxic turtle (Trachemys scripta) striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:803–807. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199807000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton SL, Thompson JW, Lutz PL. Mechanisms for maintaining extracellular glutamate levels in the anoxic turtle striatum. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1317–1323. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00484.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Ogawa T, Iwamoto T, Shimamoto K, Iimura O. Dipyridamole potentiates the myocardial infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning. Circulation. 1992;86:979–985. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AN, Fiskum G, Beal MF. Mitochondria in neurodegeneration: bioenergetic function in cell life and death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:231–245. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka H, Ohta S, Tanaka J, Toku K, Kumon Y, Maeda N, Sakanaka M, Sakaki S. Cytochrome c release from mitochondria to the cytosol was suppressed in the ischemia-tolerance-induced hippocampal CA1 region after 5-min forebrain ischemia in gerbils. Neurosci Lett. 2000;278:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00894-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson GE, Lutz PL. Release of inhibitory neurotransmitters in response to anoxia in turtle brain. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R32–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson GE, Lutz PL. Adenosine release in the anoxic turtle brain: a possible mechanism for anoxic survival. J Exp Biol. 1992;162:345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson GE, Lutz PL. Anoxia tolerant brains. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:475–486. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitatori T, Sato N, Waguri S, Karasawa Y, Araki H, Shibanai K, Kominami E, Uchiyama Y. Delayed neuronal death in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of the gerbil hippocampus following transient ischemia is apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1001–1011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01001.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pek M, Lutz PL. Role for adenosine in channel arrest in the anoxic turtle brain. J Exp Biol. 1997;200:1913–1917. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.13.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon M, Basit A, Dave K, Busto R, Veauvy C, Saul I, Ginsberg M, Sick T. Effect of the first window of ischemic preconditioning on mitochondrial dysfunction following global cerebral ischemia. Mitochondrion. 2002;2:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1567-7249(02)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon M, Bedford J, Rosenthal M, Lutz P, Sick T. Soc for Neuroscience. Vol. 17. 1991. Metabolic adaptations to anoxia in the isolated turtle cerebellum; p. 1269. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Born JG. Rapid preconditioning neuroprotection following anoxia in hippocampal slices: role of K+ATP channel and protein kinase C. Neuroscience. 1999a;89:453–459. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Chan CY, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Membrane and synaptic activity during anoxia in the isolated turtle cerebellum. Am J Physiol. 1992a;263:R1057–1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.5.R1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Lutz PL, Sick TJ, Rosenthal M. Adenosine, a “retaliatory” metabolite, promotes anoxia tolerance in turtle brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:728–732. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Mumford PL, Carranza V, Sick TJ. Calcium influx from the extracellular space promotes NADH hyperoxidation and electrical dysfunction after anoxia in hippocampal slices. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol. 1997a;18:215–221. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199802000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Mumford PL, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Anoxic preconditioning in hippocampal slices: role of adenosine. Neuroscience. 1996;75:687–694. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Mumford PL, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Antioxidants, mitochondrial hyperoxidation and electrical activity recovery after anoxia in hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1997b;754:163–170. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Rosenthal M, Lutz PL, Sick TJ. Anoxic survival of the isolated cerebellum of the turtle Pseudemis scripta elegans. J Comp Physiol B. 1992b;162:68–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00257938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ, Lutz PL, Pablo J, Mash D. Downregulation of sodium channels during anoxia: a putative survival strategy of turtle brain. Am J Physiol. 1992c;262:R712–715. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.4.R712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Xu GP, Born J, Lorenzo J, Busto R, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Cytochrome c is released from mitochondria into the cytosol following cerebral anoxia or ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol. 1999b;19:39–43. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Xu GP, Dietrich WD, Rosenthal M, Sick TJ. Rapid preconditioning protects rats against ischemic neuronal damage after 3 but not 7 days of reperfusion following global cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997c;17:175–182. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval AP, Dave K, Mochly-Rosen D, Sick T, Perez-Pinzon M. εPKC is required for the induction of tolerance by ischemic and NMDA - mediated preconditioning in the organotypic hippocampal slice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:384–391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00384.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval AP, Dave KR, Perez-Pinzon MA. Resveratrol mimics ischemic preconditioning in the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005 doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600262. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roine RO, Kajaste S, Kaste M. Neuropsychological sequelae of cardiac arrest. Jama. 1993;269:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Feng ZC, Raffin CN, Harrison M, Sick TJ. Mitochondrial hyperoxidation signals residual intracellular dysfunction after global ischemia in rat neocortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol. 1995;15:655–665. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Mumford PL, Sick TJ, Perez-Pinzon MA. Mitochondrial hyperoxidation after cerebral anoxia/ischemia - Epiphenomenon or precursor to residual damage? Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;428:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinder AF, Olson EC, Spitzer NC, Montal M. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary event in glutamate neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6125–6133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06125.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JE, Qian YZ, Gross GJ, Kukreja RC. The ischemia-selective K-ATP channel antagonist, 5- hydroxydecanoate, blocks ischemic preconditioning in the rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1055–1060. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Rose J, Heusch G. Involvement of activation of ATP-dependent potassium channels in ischemic preconditioning in swine. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1341–1352. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr A, Reid KH, Tseng MT, West C, Rigor BM. Adaptation of adult brain tissue to anoxia and hypoxia in vitro. Brain Res. 1986;374:244–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciamanna MA, Zinkel J, Fabi AY, Lee CP. Ischemic injury to rat forebrain mitochondria and cellular calcium homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1134:223–232. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90180-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinno K, Zhang L, Eubanks TH, Carlen PL, Wallace MC. Transient ischemia induces an early decrease of synaptic transmission in CA1 neurons of rat hippocampus: Electrophysiologic study in brain slices. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:955–966. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199709000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sick TJ, Chasnoff EP, Rosenthal M. Potassium ion homeostasis and mitochondrial redox status of turtle brain during and after ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:R531–540. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.248.5.R531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sick TJ, Lutz PL, LaManna JC, Rosenthal M. Comparative brain oxygenation and mitochondrial redox activity in turtles and rats. J Appl Physiol. 1982a;53:1354–1359. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.6.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sick TJ, Rosenthal M, LaManna JC, Lutz PL. Brain potassium ion homeostasis, anoxia, and metabolic inhibition in turtles and rats. Am J Physiol. 1982b;243:R281–288. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1982.243.3.R281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siesjo BK, Bendek G, Koide T, Westerberg E, Wieloch T. Influence of acidosis on lipid peroxidation in brain tissues in vitro. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5:253–258. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siesjo BK, Smith ML. The biochemical basis of ischemic brain lesions. Arzneimittelforschung. 1991;41:288–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims NR, Pulsinelli WA. Altered mitochondrial respiration in selectively vulnerable brain subregions following transient forebrain ischemia in the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1987;49:1367–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L. Circulation and energy metabolism of the brain. Raven Press, Ltd; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Fahrner A, Kiessling M. [3H]muscimol binding to gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors is upregulated in CA1 neurons of the gerbil hippocampus in the ischemia-tolerant state. Stroke. 2002;33:1698–1705. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016404.14407.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Calderone A, Jover T, Grooms SY, Yokota H, Zukin RS, Bennett MV. Ischemic preconditioning acts upstream of GluR2 down-regulation to afford neuroprotection in the hippocampal CA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2362–2367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261713299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida A, Liu GS, Mullane K, Downey JM. Acadesine lowers temporal threshold for the myocardial infarct size limiting effect of preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:116–120. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida A, Yang XM, Burckhartt B, Mullane KM, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Acadesine extends the window of protection afforded by ischaemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:379–383. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkle DM, Chien GL, Wolff RA, Soifer BE, Kuzume K, Davis RF. Cardioprotection provided by adenosine receptor activation is abolished by blockade of the KATP channel. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H829–839. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.2.H829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlessis AA, Widener LL, Bartos D. Effect of peroxide, sodium, and calcium on brain mitochondrial respiration in vitro: potential role in cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. J Neurochem. 1990;54:1412–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DM, Walker JM, Yellon DM. Global myocardial ischemia protects the myocardium from subsequent regional ischemia. Cardioscience. 1993;4:263–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson BD, Ginsberg MD. Ischemic injury in the brain. Role of oxygen radical-mediated processes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;559:269–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb22615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh FA, Marcy VR, Sims RE. NADH fluorescence and regional energy metabolites during focal ischemia and reperfusion of rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:459–465. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh FA, Vannucci RC, Brierley JB. Columnar alterations of NADH fluorescence during hypoxia-ischemia in immature rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1982;2:221–228. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1982.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial depolarization in glutamate-stimulated neurons: An early signal specific to excitotoxin exposure. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5688–5697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05688.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondria accumulate Ca2+ following intense glutamate stimulation of cultured rat forebrain neurones. J Physiol-London. 1997;498:31–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Liu XS, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado AM, Cai JY, Peng TI, Jones DP, Wang XD. Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: Release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science. 1997;275:1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Gross GJ. A comparison of adenosine-induced cardioprotection and ischemic preconditioning in dogs: Efficacy, time course, and role of KATP channels. Circulation. 1994;89:1229–1236. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]