SUMMARY

Formation of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) requires agrin, a factor released from motoneurons, and MuSK, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase that is activated by agrin. However, how signal is transduced from agrin to MuSK remains unclear. Here we report that low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-related protein (LRP) 4 (LRP4) functions as a co-receptor of agrin. LRP4 is specifically expressed in myotubes and is concentrated at the NMJ. The extracellular domain of LRP4 interacts with neuronal, but not muscle, agrin. Expression of LRP4 enables agrin binding activity and MuSK signaling in cells that otherwise does not respond to agrin. Suppression of LRP4 expression attenuates agrin binding activity, agrin-induced MuSK tyrosine phosphorylation and AChR clustering in muscle cells. LRP4 also interacts with MuSK in a manner that is stimulated by agrin. Finally, we showed that LRP4 becomes tyrosine-phosphorylated in agrin-stimulated muscle cells. These observations identify LRP4 as a functional co-receptor of agrin that is necessary for agrin-induced MuSK signaling and AChR clustering.

INTRODUCTION

The NMJ is a cholinergic synapse that conveys signals from motor neurons to muscle cells. It has served as an informative model of synaptogenesis because of its simplicity and accessibility (Sanes and Lichtman, 1999; Sanes and Lichtman, 2001). NMJ formation requires communication between presynaptic motor neurons and postsynaptic muscle fibers (Brandon et al., 2003; Fu et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008; Sanes and Lichtman, 2001). Agrin is a main nerve-derived organizer of postsynaptic differentiation at the NMJ (McMahan, 1990). Mice lacking agrin displayed severe deficits in NMJ formation (Gautam et al., 1996). Introduction of agrin into denervated muscles elicits formation of postsynaptic apparatus (Bezakova et al., 2001; Gesemann et al., 1995; Herbst and Burden, 2000; Jones et al., 1997). MuSK is a component of the agrin receptor complex (DeChiara et al., 1996; Jennings et al., 1993; Lin et al., 2001; Valenzuela et al., 1995; Yang et al., 2001). MuSK mutant mice do not form the NMJ and prepattern of aneuronal AChR-rich sites in the central region (Kim and Burden, 2008; Lin et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). Moreover, agrin induces rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of MuSK in cultured muscle cells (Glass et al., 1996a). Agrin is no longer able to induce AChR clusters in MuSK−/− myotubes and the agrin sensitivity can be restored by the introduction of wild-type MuSK (Glass et al., 1996a; Zhou et al., 1999). These observations provide evidence that agrin functions by stimulating MuSK. A fundamental gap in our understanding of agrin/MuSK signaling, despite of its essential role for NMJ formation and maintenance (Hesser et al., 2006; Kim and Burden, 2008), is poor understanding of how signals are transmitted from agrin to MuSK because the two proteins do not interact directly (Glass et al., 1996a). A hypothetical molecule MASC (myotube associated specificity component) was proposed to serve as a binding partner for agrin to transduce signals to MuSK (Glass et al., 1996a). Despite extensive studies, the identity of this co-receptor of agrin remains unclear.

LRP4 [or MEGF7 for multiple epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domain 7] is a member of the LDLR family, and contains a large extracellular N-terminal region that possesses multiple EGF repeats and LDLR repeats, a transmembrane domain and a short C-terminal region without an identifiable catalytic motif (Johnson et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2006; Yamaguchi et al., 2006). It was identified by a motif trap screen of genes encoding proteins with multiple EGF domains (Nakayama et al., 1998). Remarkably, LRP4 is required for NMJ formation as well as the development of the limb, lung, kidney, and ectodermal organs (Johnson et al., 2005; Simon-Chazottes et al., 2006; Weatherbee et al., 2006). Mice lacking LRP4 die at birth with deficits that resemble the phenotype observed in MuSK mutant mice (Weatherbee et al., 2006). The phenotypic similarity suggested that LRP4 plays a role in MuSK signaling (Weatherbee et al., 2006). However, molecular mechanisms of how LRP4 regulates NMJ formation remain unclear.

Here we provide evidences that LRP4 functions as a co-receptor of agrin. LRP4 is expressed specifically in myotubes and concentrated at the NMJ. The extracellular domain of LRP4 binds to neuronal, but not muscle, agrin. LRP4 also interacts with MuSK in a manner enhanced by agrin. Suppression of LRP4 expression attenuated agrin binding activity, agrin-induced MuSK tyrosine phosphorylation and AChR clustering in muscle cells. LRP4 expression, on the other hand, reconstitutes agrin binding and MuSK activation by agrin in cells that would otherwise not respond to agrin. These observations identify LRP4 as a key component of the receptor complex of agrin.

RESULTS

LRP4 is expressed specifically in myotubes and concentrated at the NMJ

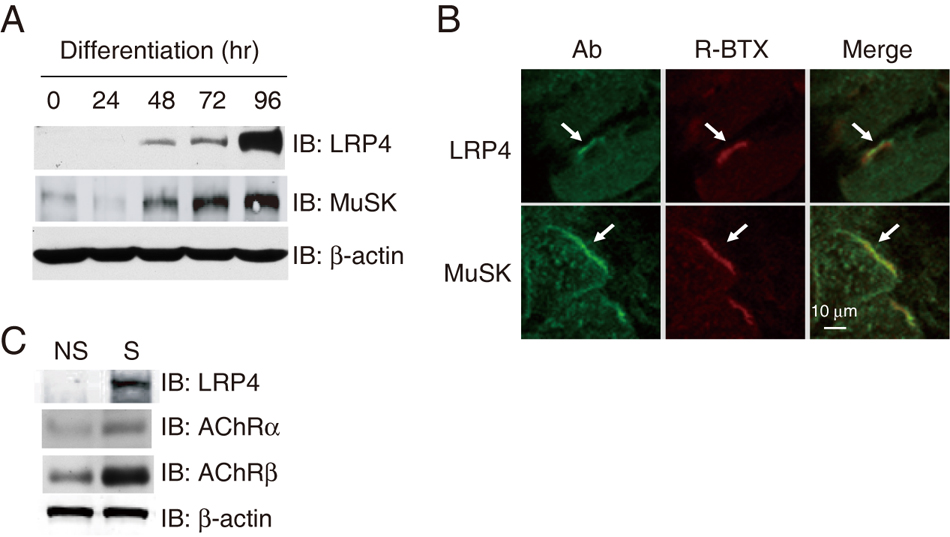

Because neuronal agrin binds only to myotubes, but not myoblasts (Glass et al., 1996b), we characterized the expression of LRP4 in developing myotubes. C2C12 myoblasts were switched fusion medium to induce muscle differentiation. Under these conditions, myotubes began to form 48 hr after medium switch (Luo et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2003; Si et al., 1996). Developing myotubes were collected and LRP4 expressed analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-LRP4 antibody. As shown in Figure 1A, LRP4 was barely detectable in myoblasts, but its expression gradually increased as myotubes matured. As control, expression of MuSK was examined in same preparations, whose expression was known to be regulated by muscle differentiation (Glass et al., 1996b; Ip et al., 2000; Valenzuela et al., 1995) (Figure 1A). These results indicate that LRP4, like MuSK, is expressed in well differentiated myotubes, but not myoblasts. Next, we investigated LRP4 distribution in vivo by staining muscle sections with anti-LRP4 antibody. The immunoreactivity of LRP4, as well as MuSK, showed a pattern of labeling similar to that of rhodamine-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (R-BTX) that labels AChRs (Figures 1B), suggesting that LRP4, like MuSK, is enriched at the NMJ. This notion was supported by results from immunoblot analysis of LRP4 expression of muscles. Hemi-diaphragms were divided into three regions: the central, narrow region, where NMJs are enriched, as synaptic region; the region close to ligaments to the ribs as non-synaptic region; and the middle in between. The AChR was enriched in the synaptic, but not non-synaptic, region (Figure 1C). In agreement with results of immunostaining, LRP4 was readily detectable in the synaptic region where AChRs were enriched. However, little, if any, LRP4 was found in the non-synaptic region. Together these results demonstrated that LRP4 is specifically expression in myotubes and is enriched at the NMJ, suggesting a role of LRP4 in NMJ formation.

Figure 1. LRP4 is specifically expressed in myotubes and concentrated at the NMJ.

(A) Temporal expression pattern of LRP4 during muscle differentiation. C2C12 myoblasts were switched to the differentiation medium. Muscle cells were collected at indicated times and lyzed. Lysates (30 µg of protein) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by immunoblotting using indicated antibodies.

(B) Colocalization of LRP4 with R-BTX in muscle sections. Diaphragm sections were incubated with polyclonal antibodies against LRP4 or MuSK, which h was visualized by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody. R-BTX was included in the reaction to label postsynaptic AChRs. Arrows indicate co-localization of LRP4 or MuSK with AChRs.

(C) Enrichment of LRP4 in synaptic regions of muscles. Synaptic (S) and non-synaptic (NS) regions of hemi-diaphragms were isolated and homogenized. Homogenates (30 µg of protein) were analyzed for LRP4 or AChR (as control) using specific antibodies. Samples were also probed for β-actin to indicate equal loading.

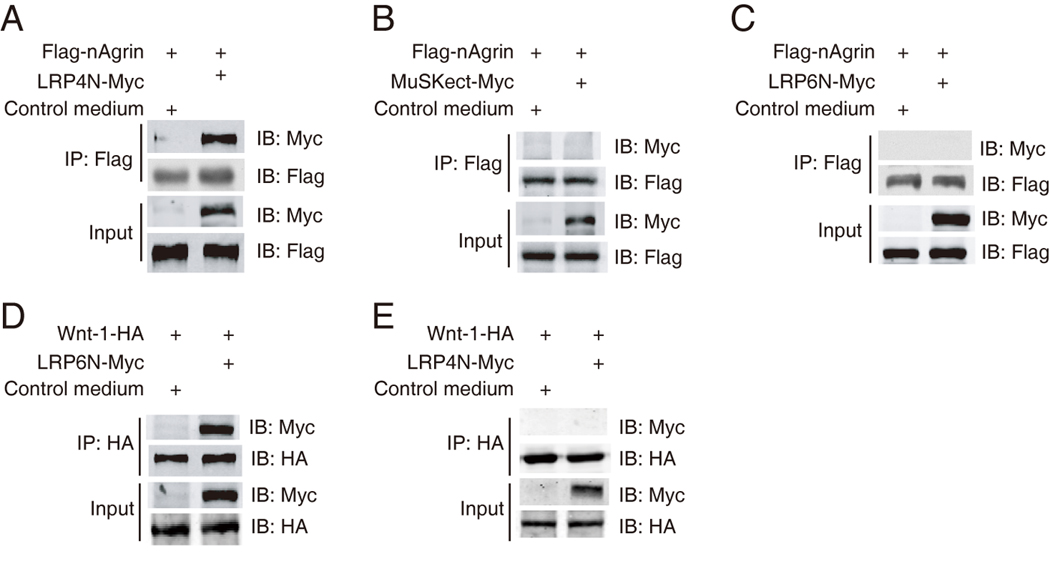

The LRP4 extracellular domain binds to neuronal agrin

Next, we determined whether agrin binds to LRP4. A secreted form of neuronal agrin, Flag-nAgrin, was generated that comprised the C-terminus of neuronal agrin fused with the Flag epitope, and a secreted form of LRP4 (i.e., LRP4N–Myc), which consisted of the LRP4 extracellular domain tagged by the Myc epitope. Flag-nAgrin was immobilized on beads and incubated with LRP4N-Myc. As shown in Figure 2A, LRP4N–Myc was precipitated with neuronal agrin, suggesting that the two proteins interact in solution. In contrast, Flag-nAgrin did not precipitate MuSKect–Myc, which consisted of the extracellular region of the kinase (Figure 2B), in agreement with previous findings that agrin and MuSK do not directly bind to each other (Glass et al., 1996a). Moreover, Flag-nAgrin did not interact with LRP6N-Myc, which comprised Myc-tagged extracellular domain of LRP6, a homologous member of the LRP family whose extracellular structural organization resembles that of LRP4 (Figure 2C). As control, LRP6N-Myc was able to interact with Wnt-1-HA when the two proteins were incubated together (Figure 2D), indicating proper folding and specific binding of LRP6N-Myc. Furthermore, LRP4N-Myc did not co-precipitate with Wnt-1-HA (Figure 2E), suggesting that the two proteins do not interact. These results demonstrate that agrin binds specifically to the extracellular domain of LRP4, but not that of MuSK, or LRP6 and on the other hand, Wnt-1 interacts with LRP6, but not LRP4. In support of this notion, the extracellular domain of LRP4 was able to neutralize neuronal agrin and thus prevented it from stimulating MuSK tyrosine phosphorylation and AChR clustering (Figure S1).

Figure 2. The LRP4 extracellular domain interacts with neuronal agrin.

(A)–(C) Interaction of LRP4 and neuronal agrin in solution. Beads were conjugated with Flag-nAgrin, which were subsequently incubated with condition media of HEK293 cells expressing LRP4N-Myc (A), MuSKect-Myc (B), LRP6N-Myc (C), or empty vector (control). Bound proteins were isolated by bead precipitation, resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. Flag-nAgrin interacted with LRP4N-Myc (A), but not MuSKect-Myc (B) or LRP6N-Myc (C).

(D) Interaction of Wnt-1 and LRP6N. Beads were conjugated with Wnt-1-HA, which were subsequently incubated with LRP6N-Myc. Bound LRP6N-Myc was revealed by immunoblotting.

(E) No interaction between Wnt-1 and LRP4N. Beads were conjugated with Wnt-1-HA, which were subsequently incubated with LRP4N-Myc. Bound LRP4N-Myc was revealed by immunoblotting.

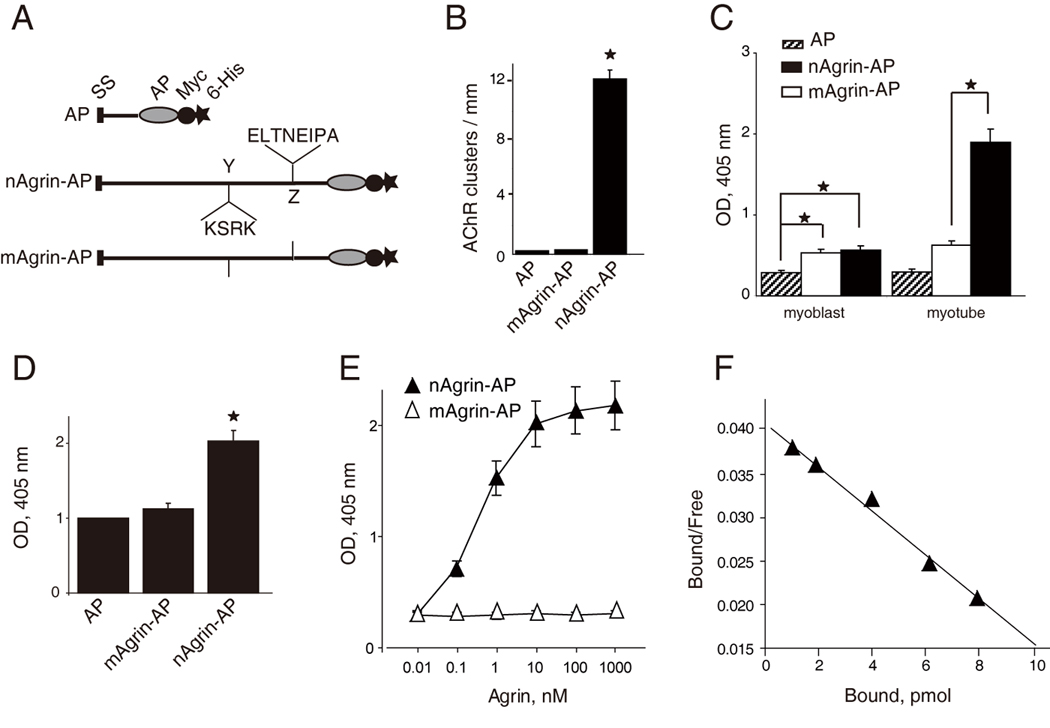

To determine whether the interaction is direct, we produced recombinant agrins, nAgrin-AP and mAgrin-AP, which contained the C-terminal region of neuronal and muscle agrin, respectively. They were fused with the heat-insensitive human placental isozyme of alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Flanagan and Cheng, 2000) (Figure 3A). The activity of the AP recombinant proteins was tested in AChR cluster assays. As shown in Figure 3B, nAgrin-AP was able to stimulate AChR clustering in C2C12 myotubes, indicating proper folding of the recombinant neuronal agrin protein. In contrast, mAgrin-AP or AP alone had little effect on AChR clustering. Next, we characterized the binding activity of the AP proteins to muscle cells by in-cell assays as described in Experimental Procedures. AP binding to myoblasts or myotubes was minimal (Figure 3C). mAgrin-AP binding to myoblasts was higher than that of AP alone, presumably because myoblasts express alpha-dystroglycan to which muscle agrin is known to interact (Bowe et al., 1994; Campanelli et al., 1996; Campanelli et al., 1994; Gee et al., 1994; Gesemann et al., 1996; Hopf and Hoch, 1996; Sugiyama et al., 1994). The mAgrin-AP binding to myotubes was higher in comparison with that in myoblasts because alpha-dystroglycan expression was increased during muscle differentiation. nAgrin-AP binding to myoblasts was similar to that of mAgrin-AP (Figure 3C). However, nAgrin-AP binding was significantly higher in myotubes than in myoblasts (Figure 3C), in agreement with earlier reports (Glass et al., 1996a) and the LRP4 expression pattern in developing muscle cells (Figure 1). These results demonstrate differential ability of recombinant muscle and neuronal agrins in binding to myotubes. Having established that nAgrin-AP was able to bind to myotubes and stimulate AChR clustering, we next characterized the interaction between LRP4 and nAgrin-AP. LRPN4-Myc was purified and immobilized on plates and incubated with purified nAgrin-AP. After wash, the AP activity bound to immobilized LRPN4-Myc was assayed by a modified ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). In comparison with control (AP alone), there was a significant increase in AP activity when nAgrin-AP were incubated with LRP4N-Myc (Figure 3D), suggesting direct interaction between the two proteins, i.e., independent of a third protein. Quantitatively, the interaction between neuronal agrin and LRP4 was dose-dependent, saturable, and of high affinity (Kd values of 0.5 ± 0.053 nM) (Figure 3E and 3F). This affinity is comparable to that (0.1–0.5 nM) of LRP6 for Dkk1 and Dkk2 (Bafico et al., 2001; Mao et al., 2001; Semenov et al., 2001). In contrast, muscle agrin, which lacks four and eight amino acid inserts at the Y and Z sites, respectively (Figure 3A) and is 1000 times less potent than neuronal agrin in stimulating AChR clusters (Gesemann et al., 1995; Reist et al., 1992), did not appear to bind to LRP4 (Figure 3D). The binding of LRP4N-Myc to muscle agrin was minimal even at high concentrations (Figure 3E). Together, these results suggest LRP4 binds specifically to neuronal agrin with high affinity. These results indicate that LRP4 binds to neuronal, but not muscle, agrin in a manner that is concentration-dependent, saturable and of high affinity.

Figure 3. High-affinity and specific interaction between of LRP4-neuronal agrin.

(A) Schematic diagrams of AP constructs. Neuronal or muscle agrin was fused to AP in pAPtag-5. The fusion proteins contain a signal peptide (SS) in the N-terminus, and two additional tags (Myc and His) in the C-terminus. Neuronal agrin contains 4- and 8-amino acid residue inserts at the Y and Z sites, respectively.

(B) Functional characterization of agrin-AP recombinant proteins. C2C12 myotubes were stimulated with AP alone, mAgrin-AP or nAgrin-AP for 18 hr. AChR clusters were assayed as described in Experimental Procedures. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 4; *, P < 0.05 in comparison with AP or mAgrin-AP.

(C) Differential binding activities of mAgrin-AP and nAgrin-AP to myoblasts and myotubes. C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes were incubated AP alone, mAgrin-AP or nAgrin-AP for 90 min at room temperature. Endogenous AP was inactivated by heating and bound AP was assayed by staining with BCIP/NBT. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 6; *, P < 0.05.

(D) Direct interaction between LRP4 and neuronal agrin. LRP4-Myc was purified and coated on Maxi-Sorp Immuno Plates, which were incubated with nAgrin-AP or mAgrin-AP. AP activity was measured with pNPP as substrate. Control, condition medium of HEK293 cells transfected with the empty pAPtag-5. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 3; *, P < 0.05 in comparison with AP or mAgrin-AP.

(E) Dose-dependent interaction between LRP4 and neuronal Agrin. Purified LRP4-Myc was coated on Maxi-Sorp Immuno Plates, which were incubated with nAgrin-AP or mAgrin-AP. AP activity was measured with pNPP as substrate. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 4; *, P < 0.05.

(F) Scatchard plot of data in E. Y axis represents the ratio of bound to free nAgrin-AP whereas X axis represents the concentration of bound nAgrin-AP.

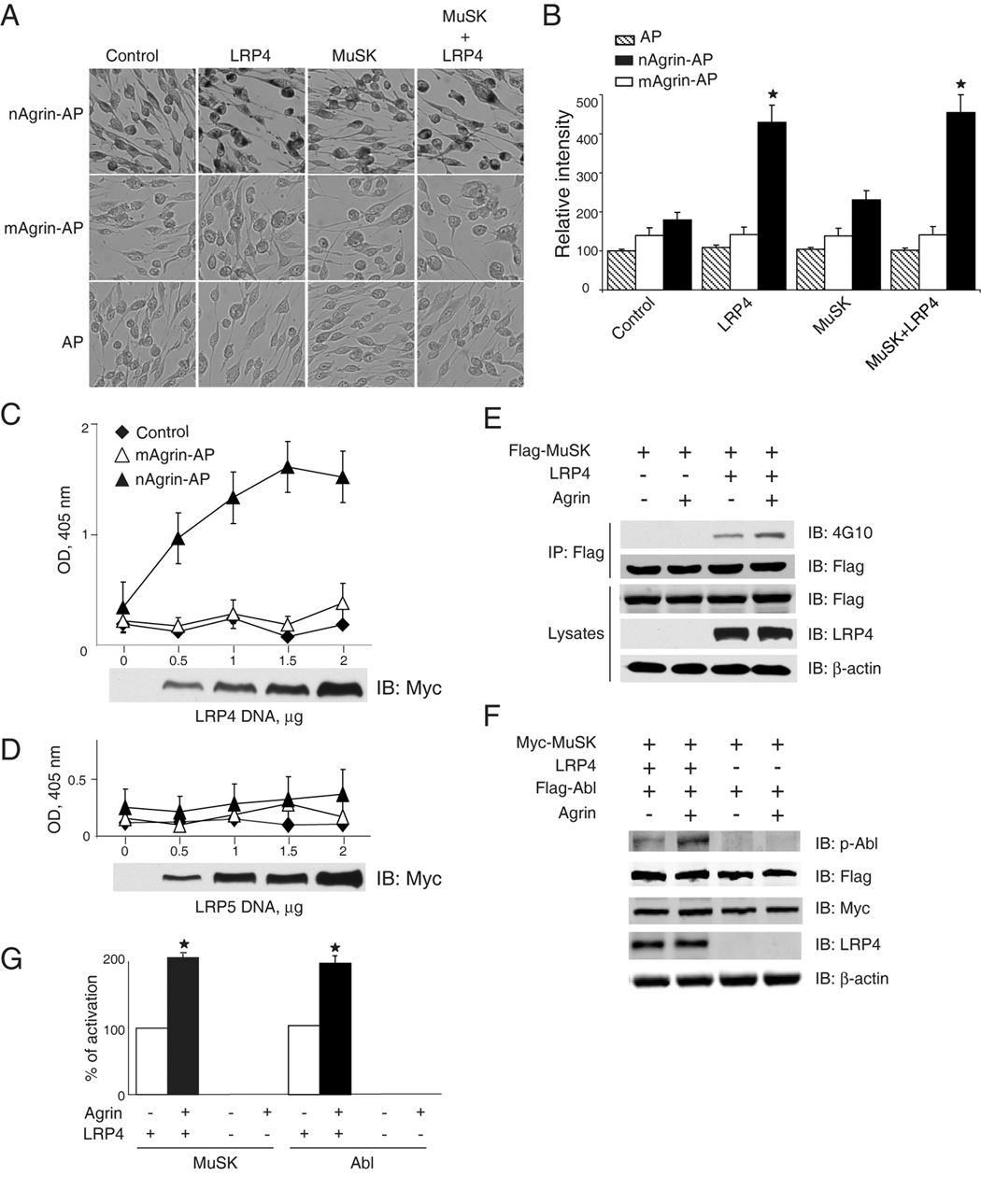

Reconstitution of neuronal agrin binding and signaling in transfected cells

To determine whether agrin binds to LRP4 in vivo, we expressed exogenous LRP4 in C2C12 myoblasts that, unlike myotubes, do not bind neuronal agrin (Glass et al., 1996a) (Figure 3C). Myoblasts were transfected with full length LRP4 or the empty vector (as control). Intact transfected myoblasts were incubated with AP alone, nAgrin-AP or mAgrin-AP. The AP activity bound to cell surface was measured in situ after heat inactivation of endogenous AP. As shown in Figure 4A and 4B, when incubated with AP alone, control and LRP4-transfected myoblasts show no difference in AP activity. However, nAgrin-AP binding was significantly higher to LRP4-transfected myoblasts in comparison with control, indicating that LRP4 enables myoblasts to interact with neuronal agrin. By contrast, transfection of MuSK had no consistent effect on binding to nAgrin-AP, in agreement with earlier observations that agrin does not bind to MuSK (Glass et al., 1996a) (Figure 2B). In addition to myoblasts, HEK293 cells were able to bind to nAgrin-AP after LRP4 transfection (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Expression of LRP4 enables binding activity for neuronal agrin and MuSK signaling.

(A) Neuronal, but not muscle, agrin bound to intact C2C12 myoblasts transfected with LRP4. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected by empty vector (control), LRP4 and/or Flag-MuSK. 36 hr after transfection, myoblasts were incubated with AP alone, mAgrin-AP or nAgrin-AP for 90 min at room temperature. Endogenous AP was inactivated by heating and bound AP was visualized in cells by staining with BCIP/NBT.

(B) Quantification of data in A. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 6; *, P < 0.05 in comparison with mAgrin-AP of the same group or nAgrin-AP in the control group.

(C, D) nAgrin-AP bound to HEK293 cells expressing LRP4, but not those expressing LRP5. HEK293 cells were transfected without (control) or with LRP4-Myc (C) or LRP5-Myc (D). 36 hr after transfection, transfected cells were incubated with nAgrin-AP or mAgrin-AP. In some experiments, control cells were incubated with nAgrin-AP. After heat inactivation of endogenous AP, lysates were assayed for transfected AP using pNPP as substrate. Lysates were also subjected to immunoblotting to reveal the expression of different amounts of LRP4-Myc (C) and LRP5-Myc (D). Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 6.

(E, F) LRP4 expression enabled MuSK and Abl activation by agrin in HEK293 cells. Cells were transfected with LRP4 and/or Flag-MuSK (E) or Flag-Abl (F). 36 hr after transfection, cells were treated without or with neuronal agrin for 1 hr and were then lyzed. In E, lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibody, and resulting immunocomplex was analyzed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10. In F, active Abl was revealed by immunoblotting with specific phospho-Abl antibody. Lysates were also blotted for Flag and/or Myc, LRP4, or β-actin to indicate equal amounts of proteins.

(G) Quantitative analysis of data in E and F. MuSK and Abl phosphorylation was quantified by using the ImageJ software. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 3; *, P < 0.05 in comparison with control.

The in situ binding activity generated by transfected LRP4 had the following characters. First, it was dose-dependent. Increase in LRP4 expression in transfected HEK293 cells led to higher nAgrin-AP binding activity (Figure 4C). Probably due to rate-limiting surface integration of overexpressed LRP4, nAgrin-AP binding was not further increased in cells transfected with 2 µg of DNA. Earlier studies have reported that overexpressed LRP4 is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (Lu et al., 2007; Obermoeller-McCormick et al., 2001). Notice that the blot reveals total, but not surface, LRP4 (Figure 4C). Second, LRP4 binding was specific for neuronal agrin because the amount of mAgrin-AP bound to transfected myoblasts and HEK293 cells was minimal, and not concentration-dependent (Figure 4A–4C). Notice that mAgrin-AP, like nAgrin-AP, also contained the AP and the Myc and His tags. Inability of mAgrin-AP to bind to LRP4-transfected cells indicate that binding to LRP4 does not involve the AP or tags. Third, the binding activity was LRP4 specific. Expression of LRP5, another member of the LRP family (Herz and Bock, 2002), did not increase agrin binding in transfected cells (Figure 4D). Last, nAgrin-AP binding was similar between cells transfected with LRP4 alone and those co-transfected with LRP4 and MuSK (Figure 4A and 4B), indicating that the neuronal agrin binding activity is mainly contributed by LRP4 although LRP4 and MuSK could interact in muscle cells (see below). Taken together, these results demonstrate the ability of LRP4 to reconstitute agrin binding in cells that otherwise do not interact with agrin.

Next, we determined if LRP4 was able to reconstitute MuSK signaling in cells that do not respond to agrin. MuSK is a receptor tyrosine kinase whose activation has been shown to be upstream of all known agrin signaling cascades (Fuhrer et al., 1997; Glass et al., 1997; Glass et al., 1996a; Herbst and Burden, 2000; Luo et al., 2002; Strochlic et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 1999). Therefore we first examined whether LRP4 expression enables MuSK activation by agrin in HEK293 cells that do not express LRP4 (Figure 4E). Flag-MuSK was transfected into HEK293 cells with or without LRP4 and transfected cells were stimulated with neuronal agrin. As shown in Figure 4E and 4G, agrin was unable to elicit MuSK tyrosine phosphorylation in HEK293 cells transfected with MuSK alone. Intriguingly, LRP4 co-expression enabled agrin to activate MuSK, indicating that LRP4 could be an agrin receptor able to stimulate MuSK. Basal tyrosine phosphorylation of MuSK, i.e., in the absence of agrin, was increased by LRP4, which could suggest a role of LRP4 in MuSK auto-activation, presumably by its direct interaction with the kinase (see below). Agrin-induced AChR clustering requires the intracellular tyrosine kinase Abl (Finn et al., 2003). To further investigate the role of LRP4, we examined Abl activation by anti-phospho-Abl antibody in cells co-expressing LRP4 and MuSK. As shown in Figure 4F and 4G, active Abl was barely detectable in cells transfected with Myc-MuSK alone, regardless of agrin stimulation. In contrast, agrin elicited a significant increase in phospho-Abl in cells co-expressing LRP4 and Myc-MuSK. Together, these results indicate that LRP4 expression enables binding activity for neuronal agrin, MuSK activation, and initiation of intracellular signaling in cells that otherwise do not respond to agrin.

Decrease of LRP4 levels attenuates neuronal agrin binding, MuSK activation, and induced AChR clustering in muscle cells

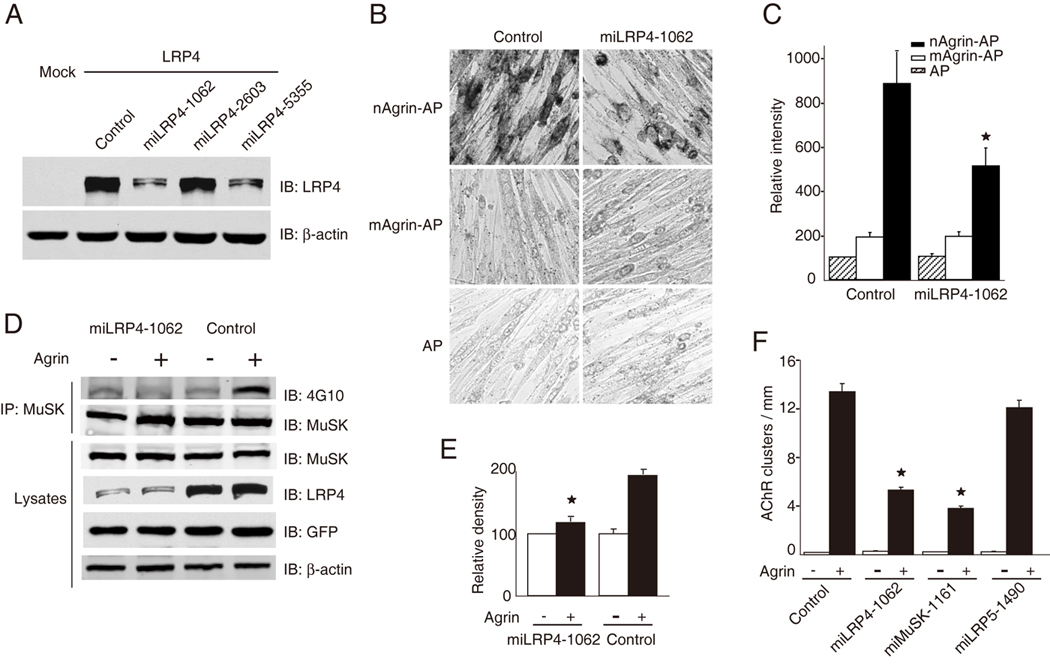

We next determined if LRP4 is necessary for agrin/MuSK signaling by a loss-of-function approach. To this end, we generated several microRNA constructs of LRP4. As shown in Figure 5A, miLRP4-1062 was most potent in inhibiting LRP4 expression. First, we determined if repression of LRP4 affects agrin binding to intact muscle cells. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with miLRP4-1062 or the control miRNA that encoded scramble sequence, and resulting myotubes were incubated with AP, mAgrin-AP or nAgrin-AP and assayed for AP activity by in-cell staining. In comparison with control miRNA, miLRP4-1062 did not appear to alter binding activity of AP and mAgrin-AP to myotubes (Figure 5B and 5C). However, myotubes transfected with miLRP4-1062 had lower levels of nAgrin-AP staining in comparison with those transfected with the control vector (Figure 5B and 5C), indicating a necessary role of endogenous LRP4 for neuronal agrin binding. Second, we tested whether LRP4 is required for agrin to stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation of MuSK. MuSK was precipitated from myotubes transfected with control miRNA or miLRP4-1062 and assayed for tyrosine phosphorylation. Expression of miRNA constructs was indicated by the presence of GFP that was encoded by the parental vector. As shown in Figure 5D, transfection of miLRP4-1062 reduced expression of endogenous LRP4, but not MuSK or β-actin. Remarkably, agrin-induced MuSK tyrosine phosphorylation was attenuated in myotubes transfected with miLRP4-1062 in comparison with control miRNA (Figure 5E). These results suggest that MuSK activation is impaired when LRP4 levels were reduced.

Figure 5. Suppression of LRP4 expression attenuates neuronal agrin binding, MuSK activation, and induced AChR clustering.

(A) Characterization of LRP4-miRNA constructs. HEK293 cells were transfected with LRP4 and LRP4-miLRP4 constructs or control miRNA that encoded scrambled sequence. Cell lysates were analyzed for LRP4 expression by immunoblotting with anti-LRP4 antibody. β-Actin was used as loading control. miLRN4-1062 was most potent in inhibiting LRP4 expression.

(B) Repression of LRP4 expression reduced neuronal agrin binding to myotube surface. C2C12 myotubes were transfected with control (scramble) miRNA or miLRP4-1062. Cells were incubated with AP, mAgrin-AP or nAgrin-AP, which was visualized in cell as described in Figure 3A.

(C) Quantitative analysis of data in B. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 6; *, p < 0.05 in comparison nAgrin-AP with control.

(D) MuSK activation by neuronal agrin was diminished in C2C12 myotubes transfected with miLRP4-1062. C2C12 myotubes were transfected with control miRNA or miLRP4-1062. 36 hr later, myotubes were treated without or with agrin for 1 hr and cells were then lyzed. MuSK was isolated by immunoprecipitation and blotted with the anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10. Lysates were also blotted for MuSK, LRP4, GFP (encoded by miRNA constructs), and β-actin to indicate equal amounts of proteins.

(E) Quantitative analysis of data in D by ImageJ software (mean ± SEM, n = 3; *, P < 0.05 in comparison with control).

(F) Neuronal agrin-induced clustering of AChRs was inhibited in C2C12 myotubes transfected with miLRP4-1062. C2C12 myotubes were transfected by control miRNA, miLRP4-1062, miMuSK-1161, or miLRP5-1490. AChR clusters were induced by neuronal agrin and quantified as described in Experimental Procedures (mean ± SEM, n = 5; *, p < 0.05 in comparison with control). miMuSK-1161 and miLRP5-1490 were able to suppress expression of respective proteins in transfected cells (data not shown).

Finally, we investigated whether LRP4 is necessary for agrin-induced AChR clustering. Myoblasts were transfected with control miRNA or miLRP4-1062, or miRNA constructs against MuSK and LRP5 that reduced expression of MuSK and LRP5, respectively (data not shown). Transfected myotubes were stimulated without or with agrin and AChR clusters in GFP-expressing myotubes scored as described previously (Zhang et al., 2007). Expression of these miRNA constructs did not appear to alter basal AChR clusters. However, the number of agrin-induced AChR clusters was reduced in myotubes transfected with miLRP4-1062 (Figure 5F), suggesting a necessary role of LRP4 in agrin-induced clustering. Similar reduction was observed in myotubes expressing miMuSK-1161, as expected. Transfection with miLRP5-1490, however, had no effect on agrin-induced AChR clustering, in agreement with the observation that LRP5 does not bind to neuronal agrin (Figure 4D).

Interaction between LRP4 and MuSK

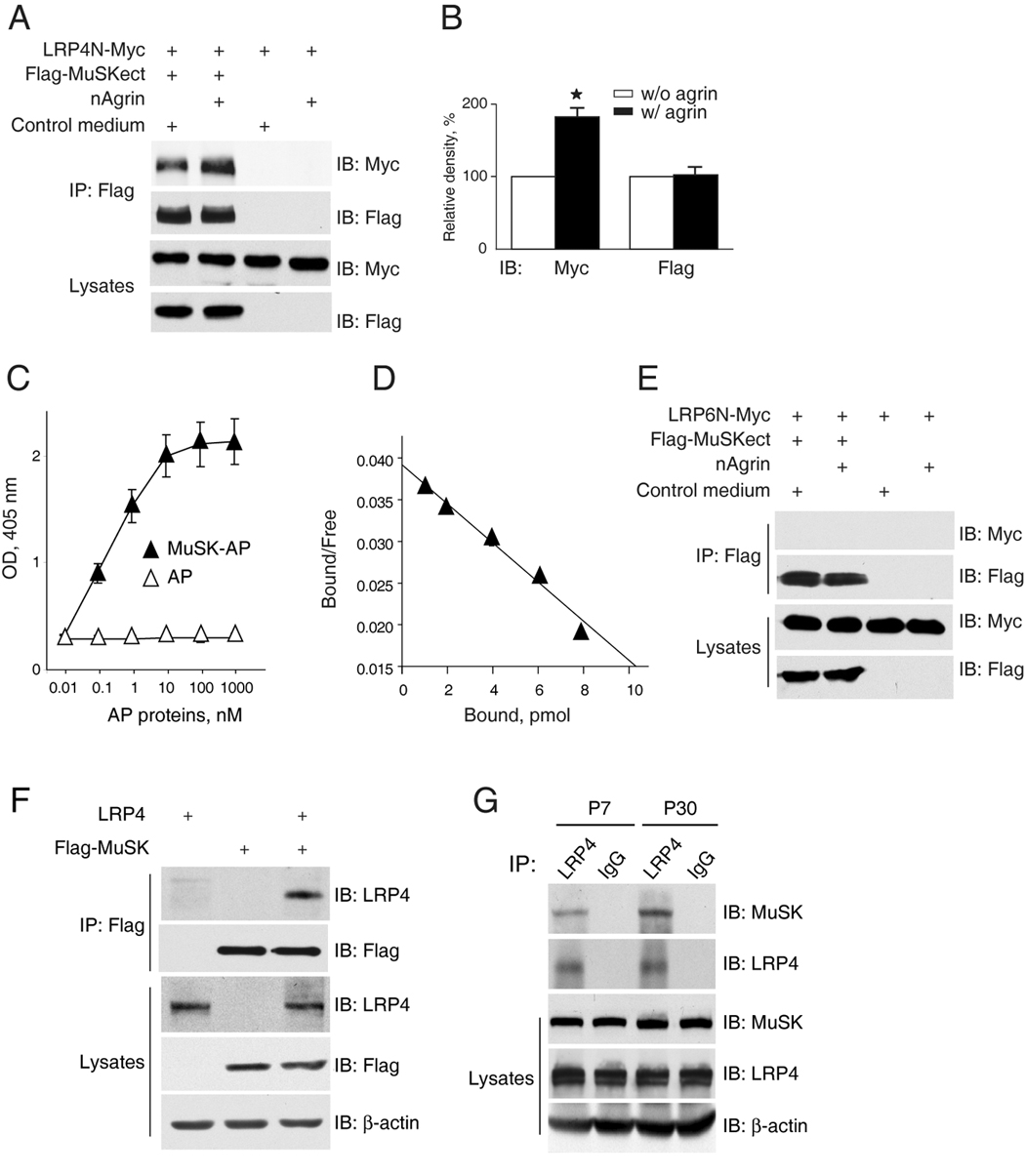

In a working model, LRP4 serves as a co-receptor that binds to agrin and, together with MuSK, stimulates AChR clustering. To examine the relationship among agrin, LRP4 and MuSK, we determined whether LRP4 interacts with MuSK and if so, if the interaction is regulated by agrin. Secreted Flag-MuSKect, which comprised the entire extracellular region of MuSK fused with the Flag epitope, was incubated with LRP4N–Myc in the absence or presence of agrin. Flag-MuSKect alone was able to co-precipitate with LRP4N–Myc (Figure 6A and 6B), indicative of direct binding between the extracellular domains of MuSK and LRP4. Quantitatively, the interaction between MuSK and LRP4 was dose-dependent and saturable, and of high affinity (Kd values of 0.45 ± 0.041 nM, Figure 6C and 6D). Interestingly, the amount of LRP4 co-precipitated with Flag-MuSKect was increased by agrin (Figure 6A and 6B). In contrast, as control, LRP6N-Myc failed to co-precipitate with Flag-MuSKect regardless of the presence or absence of agrin (Figure 6E). These observations suggest that LRP4 and MuSK form a complex in the absence of the ligand agrin; however, agrin, via binding to LRP4, enhances the LRP4-MuSK interaction. To test this hypothesis further, we examined if full length MuSK and LRP4 interact with each other in cells. LRP4 and Flag-MuSK were co-transfected into HEK293 cells. MuSK was precipitated from cell lysates by a Flag antibody and the resulting immunocomplex was analyzed for LRP4. As shown in Figure 6F, LRP4 co-precipitated with MuSK in transfected cells, in support of the notion that the two proteins interact in transfected cells. Moreover, the LRP4-MuSK association was detectable in mouse muscle homogenates (Figure 6G), suggesting in vivo interaction of the two proteins.

Figure 6. Direct interaction between LRP4 and MuSK.

(A) Increased LRP4-MuSK interaction in the presence of neuronal agrin. Flag-MuSKect immobilized on beads were incubated with condition media of cells expressing the extracellular domains of LRP4 (LRP4N-Myc) or the empty vector (control) in the presence or absence of neuronal agrin. Precipitated LRP4 was analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Myc antibody. Reaction mixtures were also blotted directly for Flag and Myc to demonstrate equal amounts of proteins.

(B) Quantitative analysis of LRP4N-Myc and Flag-MuSK. Data shown were mean ± SEM, n = 3; *, p < 0.05 in comparison with the no-agrin group.

(C) Dose-dependent interaction between LRP4 and MuSK. Purified LRP4-Myc was coated on Maxi-Sorp Immuno Plates, which were incubated with MuSK-AP. Bound AP was measured with pNPP as substrate. Data shown were mean ± SEM. n = 4.

(D) Scatchard plot of data in C. Y axis represents the ratio of bound to free MuSK-AP whereas X axis represents the concentration of bound MuSK-AP.

(E) No interaction of LRP6 and MuSK extracellular domains. Experiments were done as in A except condition medium of cells expressing the extracellular domain of LRP6 was used.

(F) Co-immunoprecipitation of LRP4 and MuSK. HEK293 cells were transfected with LRP4 and/or Flag-MuSK. Lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibody, and resulting immunocomplex was analyzed for LRP4 and Flag. Lysates were also probed to indicate equal amounts of indicated proteins.

(G) Interaction of LRP4 with MuSK in mouse muscles. Mouse muscles of indicated ages were homogenized, and homogenates were incubated with rabbit anti-LRP4 antibody or rabbit normal IgG. Precipitates were probed for MuSK and LRP4. Homogenates were also probed directly for MuSK, LRP4, and β-actin (bottom panels).

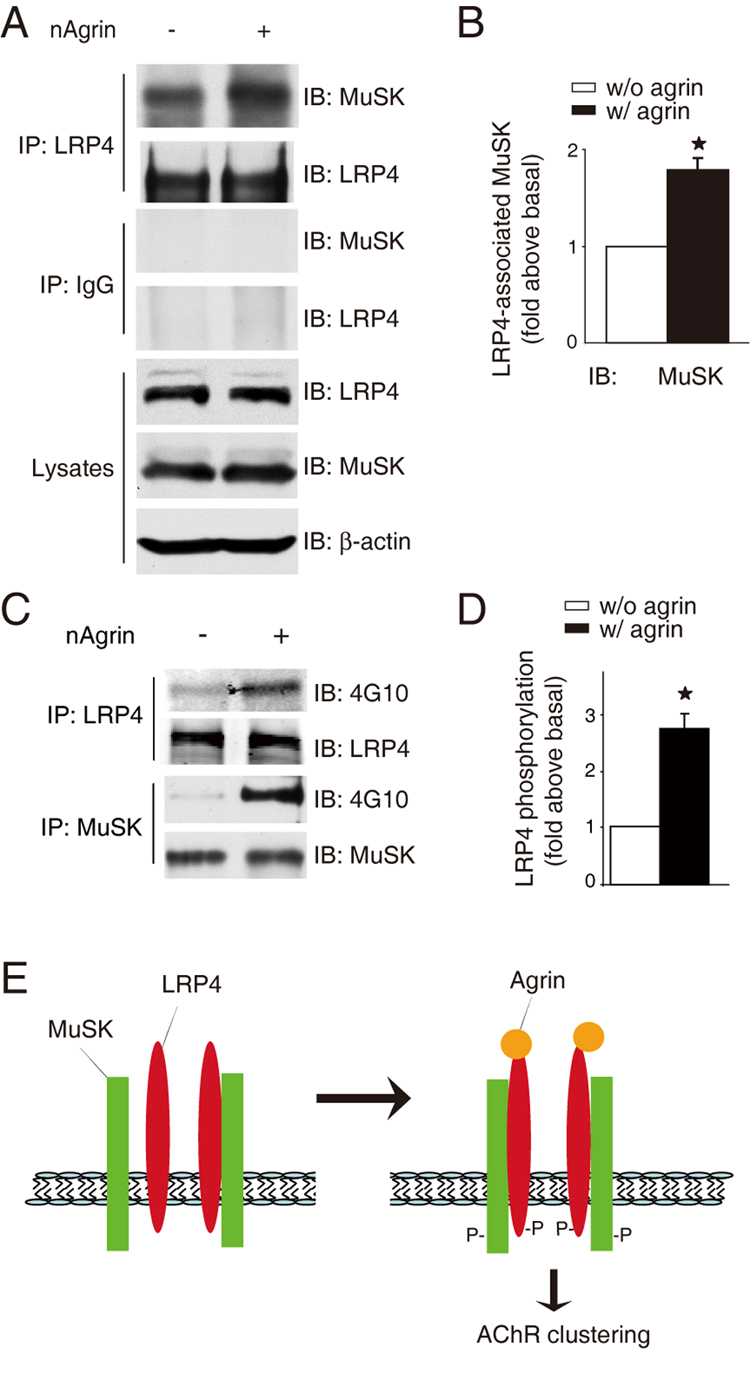

Neuronal agrin stimulates LRP4 interaction with MuSK and tyrosine phosphorylation

To further investigator the role of LRP4 in agrin signaling, we examined whether the LRP4-MuSK interaction in muscle cells is regulated by neuronal agrin. C2C12 myotubes were treated without or with agrin for 1 hr. Myotubes were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-LRP4 antibody and resulting precipitates were probed for MuSK. As shown in Figure 7A, MuSK co-precipitated with LRP4 from cells in the absence of agrin, suggesting basal interaction of the two proteins and in agreement with in vitro binding results (Figure 6A–D). The co-precipitation was increased in agrin-stimulated myotubes (Figure 7A and 7B). These observations indicate that LRP4 and MuSK form a complex in a manner that is up-regulated by agrin.

Figure 7. Agrin stimulates the LRP4-MuSK interaction and LRP4 tyrosine phosphorylation.

(A) Agrin stimulated the interaction between endogenous LRP4 and MuSK. C2C12 myotubes were stimulated without or with neuronal agrin. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-LRP4 antibody (top panels) or rabbit normal IgG (middle panels). Resulting precipitates were probed for MuSK or LRP4. Lysates were also probed with antibodies against LRP4, MuSK, or β-actin to demonstrate equal amounts (bottom panels).

(B) Quantitative analysis of data in A by using the ImageJ software (mean ± SEM, n = 3; *, P < 0.05 in comparison with the no-agrin group).

(C) Agrin stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of LRP4 in muscle cells. C2C12 myotubes were treated without or with agrin for 1 hr. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies against LRP4 and MuSK, respectively. Resulting precipitates were probed with anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody 4G10, or antibodies against LRP4 and MuSK, respectively, to indicate equal amounts of precipitated proteins.

(D) Quantitative analysis of data in C. Data shown were mean ± SEM, n = 3; *, p < 0.05 in comparison with no-nAgrin.

(E) A working model. In the absence of neuronal agrin, LRP4 could interact with MuSK and this interaction is increased by agrin stimulation. Such interaction is necessary for MuSK activation and downstream signaling that leads to AChR clustering. P, phosphorylation.

LRP4 has a large intracellular domain containing six tyrosine residues. Recent evidence indicates that LRP4, immunopurified from the brain, could be phosphorylated on serine residues presumably by CaMK II (Tian et al., 2006). Other members of the LRP family, LRP5 and LRP6, become phosphorylated upon activation of the Wnt canonical pathway (Ding et al., 2008). Unlike LRP5 and LRP6, LPR4 has a NPXY motif in the intracellular region that may be phosphorylated by a tyrosine kinase (Herz and Bock, 2002). Having demonstrated that LRP4 interacts with MuSK and the interaction is enhanced by agrin, we determined whether LRP4 itself becomes phosphorylated on tyrosine residues. C2C12 myotubes were stimulated with neuronal agrin for 1 hr and lysates were subjected immunoprecipitation of LRP4 and MuSK, respectively. Resulting precipitates were probed with the anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody 4G10. As shown in Figure 7C and 7D, LRP4 as well as MuSK became tyrosine-phosphorylated in agrin-stimulated myotubes. This result suggests a role of LRP4 in agrin signaling.

DISCUSSION

Major findings of this paper are as follows. First, LRP4 is specifically expressed in myotubes, but not myoblasts and is concentrated at the NMJ (Figure 1). Second, it is both necessary and sufficient to bind to agrin and to activate MuSK signaling that leads to AChR clustering. Using three different assays (in solution, on solid phase, and in cells), we demonstrate that neuronal agrin was able to interact directly with the extracellular region of LRP4 (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4). The binding activity of LRP4 was specific because 1) LRP4 binding to muscle agrin was minimal; 2) the binding is concentration-dependent and of high affinity with a sub-nanomolar Kd; and 3) neuronal agrin did not bind to LRP5 or LRP6, two other members of the LRP family that are highly homologous to LRP4. Third, expression of LRP4 enabled binding activity for neuronal agrin and MuSK signaling in cells that otherwise did not respond to agrin (Figure 4). Fourth, suppression of LRP4 expression attenuated agrin binding activity and agrin-induced MuSK phosphorylation and AChR clustering in muscle cells (Figure 5). Fifth, LRP4 could interact with MuSK in a manner that is increased by agrin (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Finally, LRP4 became tyrosine-phosphorylated in muscle cells in response to agrin stimulation (Figure 7). These observations indicate that LRP4 can bind to agrin and transmit signals to MuSK, suggesting that it may serve as a functional receptor for agrin. Based on these observations, we propose a working hypothesis where LRP4 interacts with MuSK at basal levels in the absence of the ligand. Upon agrin stimulation, the interaction was increased to activate MuSK and subsequent downstream signal cascades for AChR clustering (Figure 7E).

Despite the essential role of MuSK in NMJ formation, mechanisms of how it is activated and how it acts to control NMJ formation remain elusive. Recent studies have shed light on intracellular pathways downstream of MuSK. They are thought to involve the adapter protein Dok-7 (Okada et al., 2006), and several enzymes including Src-family kinase (Ferns et al., 1996; Mittaud et al., 2001; Mohamed et al., 2001; Qu and Huganir, 1994; Wallace, 1991), Abl (Finn et al., 2003), casein kinase 2 (Cheusova et al., 2006), geranylgeranyl transferase I (GGT) (Luo et al., 2003), GTPases of the Rho family (Weston et al., 2003; Weston et al., 2000), and Pak1, a serine/threonine kinase that is activated by Rho GTPases (Luo et al., 2002). Although agrin is known to activate MuSK, the two proteins, however, do not interact directly. The MASC co-receptor was hypothesized that has to be myotubes specific and is able to transmit signal from agrin to MuSK (Glass et al., 1996a). Remarkably, LRP4 is a protein specifically expressed in myotubes, not in myoblasts (Figure 1), fulfilling a requirement of MASC. Second, LRP4 is able to reconstitute agrin binding and MuSK signaling in cells that otherwise do not respond to agrin (Figure 4). Third, LRP4 is required for agrin binding and induced MuSK signaling and AChR clustering in muscle cells (Figure 5). Fourth, genetic studies have demonstrated that phenotypes of LRP4 mutant mice are similar to those in MuSK mutant (Weatherbee et al., 2006). LRP4 mutants die at birth with defects in both pre- and post-synaptic differentiation and in particular, the rapsyn-dependent scaffold fails to assemble in LRP4 mutants. These results provide strong evidence that LRP4 satisfies essential criteria of serving a functional co-receptor of agrin.

The identification of LRP4 as a co-receptor for agrin could provide insight into mechanisms of how agrin stimulation leads to AChR clustering. First, bridging agrin and MuSK, LRP4 could transmit signal to MuSK and thus activate intracellular cascades that have been identified, leading to AChR clustering. Second, LRP4 may regulate MuSK activity. MuSK and LRP4 co-precipitate in vitro and in muscle cells in the absence of agrin (Figure 6 and Figure 7), and tyrosine phosphorylation of MuSK is increased in cells co-expressing LRP4 (Figures 4E and 4G). These observations may suggest that LRP4 promotes MuSK auto-activation, presumably by regulating MuSK dimerization. Exactly how LRP4 regulates MuSK function and the stoichiometry of the LRP4-MuSK interaction warrant further investigation. Third and alternatively, LRP4 itself may function as a signal transducer. The juxtamembrane cytoplasmic region of LRP4 contains a NPXY motif. This motif in LDLR, LRP1 and LRP2 has been shown to serve as a docking site for cytoplasmic adaptor proteins through a phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain (Herz and Bock, 2002). Intriguingly, LRP4 becomes tyrosine phosphorylated upon agrin stimulation (Figure 7C and 7D). It would be interesting to investigate whether tyrosine phosphorylation of LRP4 is necessary for agrin signaling and AChR clustering and whether phosphorylated LRP4 binds to PTB domain-containing proteins. One such protein is Dok7, which is essential for NMJ formation (Okada et al., 2006).

Wnt signaling is implicated in synapse formation (Ciani and Salinas, 2005). Wnt-7a released from granule cells induces axon and growth cone remodeling in mossy fibers (Hall et al., 2000). In C. elegans, Wnt signaling positions NMJs by inhibiting synaptogenesis (Klassen and Shen, 2007). NMJ formation in Drosophila requires Wnt signaling (Mathew et al., 2005; Packard et al., 2002). However, it remains unclear whether Wnt signaling regulates mammalian NMJ formation. Wnt ligands act by binding to the receptor complex of Frizzled and LRP5/6 (Cadigan and Liu, 2006; He et al., 2004; Malbon and Wang, 2006; Schulte and Bryja, 2007). Subsequently, signal is believed to be transmitted to the adapter protein Dishevelled (Dvl), which interacts with Frizzled, to initiate intracellular canonical and non-canonical pathways. Intriguingly, MuSK, like Frizzled, interacts with both a LRP protein (i.e., LRP4) and Dvl (Luo et al., 2002). In addition, MuSK contains an extracellular CRD domain that is highly homologous to that in Frizzled that interacts with Wnt (Glass et al., 1996a; Valenzuela et al., 1995). Moreover, a number of Wnt signaling molecules including APC and β-catenin have been implicated in MuSK cascades (Li et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2007). These observations raise a question whether the agrin-LRP4-MuSK signaling is regulated by a Wnt ligand that may interact with LRP4 and/or MuSK. We showed that LRP4 does not bind Wnt-1 (Figure 2E). This, however, does not exclude possible involvement of one of the 18 other Wnt proteins in mouse (Clevers, 2006)(The Wnt Homepage: www.stanford.edu/~rnusse/wntwindow). On the other hand, the “Wnt signaling” molecules (including Dvl, APC, and β-catenin) may simply function in a manner independent of Wnt signaling in mammalian NMJ formation.

It is of interest to note that the phenotypes of MuSK and LRP4 mutant mice are more severe than those of agrin mutant. In LRP4 or MuSK mutants, but not agrin mutants, AChR clusters are absent when clusters begin to assemble at E13.5 and the rapsyn-dependent scaffold fails to assemble (Lin et al., 2001; Weatherbee et al., 2006). These observations could suggest the existence of a signaling pathway that requires MuSK and/or LRP4, but not agrin. This pathway may regulate the formation of aneuronal AChR clusters prior to the arrival of motoneuron terminals or assembly of rapsyn-dependent scaffold. It may be regulated by a ligand that could interact with MuSK and/or LRP4. In light of the above discussion, such ligand may be a Wnt protein.

Agrin is expressed in the brain (Cohen et al., 1997; Mann and Kroger, 1996; O'Connor et al., 1994). Suppression of its expression impairs dendritic development and synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons (Bose et al., 2000; Ferreira, 1999). Agrin-deficient neurons appear to be resistant to excitotoxic injury and agrin heterozygous mice are less sensitive to kainic acid-induced seizure and mortality (Hilgenberg et al., 2002). Agrin is thought to bind to the a3 subunit of Na+/K+-ATPase in neurons and thus regulates their function (Hilgenberg et al., 2006). LRP4 expression is enriched in the brain and could interact with postsynaptic scaffold proteins including PSD-95 and SAP97 (Lu et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2006; Weatherbee et al., 2006). The identification of LRP4 as a co-receptor of neuronal agrin may shed light on molecular mechanisms of how agrin and LRP4 work in the brain.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and antibodies

Taq DNA polymerase, T4 DNA ligase, and restriction enzymes were purchased from Promega. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit antibodies and enhanced chemifluoresent (ECL) reagents for Western blotting were from Amersham. Rhodamine-αBTX (R-BTX) was from Molecular Probes. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Operon Biotechnologies. Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies were purchased from Sigma (Flag M2, F3165); Torrey Pines Biolabs (GFP, TP401); Upstate Biotechnology (4G10, 05–1050); Cell Signaling (Phospho-c-Abl, 2861); Novus (β-actin, NB600-501). Rabbit anti-MuSK antibodies were described previously (Luo et al., 2002). Rabbit anti-LRP4 antibody was described previously (Lu et al., 2007). Rat anti-AChR α-subunit (mAb35) antibody was a gift from Dr. Richard Rotundo. Rat anti-AChR β-subunit (mAb124) antibody was a gift from Dr. Jon Lindstrom.

Constructs

Original agrin constructs were gifts from Zach Hall. Agrin-AP constructs were generated by fusing neuronal and muscle agrin (aa 1145–1940) (Ferns et al., 1993) with AP in pAPtag-5. To generate Flag-MuSK, the MuSK DNA was generated by PCR and subcloned in EcoRI/XbaI sites in pFlag-CMV1 downstream of an artificial signal peptide sequence and a Flag epitope. LRP4-Myc was generated by subcloning the full length LRP4 DNA into NheI and HindIII sites in pcDNA3.1-MycHis (Invitrogen) with 3 Alanines insert after amino acid 1746. LRP4N-Myc was generated by subcloning LRP4 extracellular domain DNA into NheI and NotI sites in pcDNA3.1-MycHis. LRP5 DNA was amplified with pCMV-Sports6-LRP5 (Open Biosystems) as template and subcloned into XbaI and NotI sites in pcDNA3.1-MycHis to generate LRP5-Myc. LRP4-, LRP5- and MuSK-miRNA constructs were generated using the BLOCK-iT™ Pol II miR RNAi Expression Vector Kit (Invitrogene, K4936-00). Oligonucleotide sequences for miRNA constructs were: for mi-MuSK-1161 5'-TGCTG TAACA CAGCA GAGCC TCAGC AGTTT TGGCC ACTGA CTGAC TGCTG AGGCT GCTGT GTTA-3' (sense), 5'- CTGTA ACACA GCAGC CTCAG CAGTC AGTCA GTGGC CAAAA CTGCT GAGGC TCTGC TGTGT TAC -3' (antisense); for mi-LRP5-1490 5'- TGCTG ATCAC AGGGT GCAAC ACAAT GGTTT TGGCC ACTGA CTGAC CATTG TGTCA CCCTG TGAT -3' (sense), 5'- CCTGA TCACA GGGTG ACACA ATGGT CAGTC AGTGG CCAAA ACCAT TGTGT TGCAC CCTGT GATC -3' (antisense); for mi-LRP4-1062: 5’-TGCTG TTAAC ATTGC AGTTC TCCTC AGTTT TGGCC ACTGA CTGAC TGAGG AGATG CAATG TTAA-3’ (sense), 5’-CCTGT TAACA TTGCA TCTCC TCAGT CAGTC AGTGG CCAAA ACTGA GGAGA ACTGC AATGT TAAC-3’ (antisense), for mi-LRP4-2603: 5’-TGCTG AATAC ATGTA CCCGC CCATG GGTTT TGGCC ACTGA CTGAC CCATG GGCGT ACATG TATT-3’(sense), 5’-CCTGA ATACA TGTAC GCCCA TGGGT CAGTC AGTGG CCAAA ACCCA TGGGC GGGTA CATGT ATTC-3’ (antisense), for mi-LRP4-5355: 5’-GCTGT AGCAC AGCTG ATTAT ACACG GTTTT GGCCA CTGAC TGACC GTGTA TACAG CTGTG CTA-3’(sense), 5’-CCTGT AGCAC AGCTG TATAC ACGGT CAGTC AGTGG CCAAA ACCGT GTATA ATCAG CTGTG CTAC-3’ (antisense). The authenticity of all constructs was verified by DNA sequencing. The following constructs were described previously: MuSK-AP (Wang et al., 2008); pcDNA-LRP4 (Lu et al., 2007); Wnt1-HA(Zhang et al., 2007); and Wnt1-Myc, LRP6-N-Myc, and mfz8CRD-IgG (Tamai et al., 2000).

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293 cells and mouse C2C12 muscle cells were maintained and transfected as previously described (Zhang et al., 2007). In some experiments, myotubes were transfected with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668-019). The cells were incubated with a mixture of DNA, lipofectamine and serum-free medium for 8 hr before being switched to the fusion medium. The DNA: lipofectamine ratio in the mixture was 1 µg: 2µl. The optimal volume of the mixture for 24-well dishes was 200 µl per well with 2 µg plasmid DNA.

Recombinant protein production and purification

To produce recombinant proteins, HEK293 were transfected with respective plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were switched to Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with reduced concentration (0.05%) of fetal bovine serum, and secreted proteins were harvested 24 hr later. nAgrin-AP, mAgrin-AP, or MuSK-AP recombinant proteins, which contained 6-His-tags that were encoded by pAPtag-5, were purified by affinity chromatography using TALON Resins (BD Biosciences).

Binding assays

Solution binding assay

Flag-nAgrin was immobilized to protein A Sepharose beads (that were preabsorbed with anti-Flag antibody), which were incubated with 1 ml (0.5 nM) of LRP4N-Myc, MuSKect-Myc, or LRP6N-Myc condition medium, and Flag-nAgrin-bound proteins were isolated by bead precipitation and resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by immunoblot with anti-Myc antibody. In some experiments, LRP4N-Myc, LRP6N-Myc or MuSKect-Myc was incubated with Wnt-1-HA immobilized on beads. LRP4 and LRP6 that were co-precipitated with Wnt-1 were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Myc antibody.

Solid phase binding assay

Maxi-Sorp Immuno Plates (Nunc) were coated with purified LRP4-Myc at 4°C overnight, and then incubated with 1% BSA in PBS to block non-specific binding. Coated wells were incubated with purified AP fusion proteins and the AP activity was measured using pNPP as substrate.

Intact cell binding assays

Live C2C12 myoblasts or myotubes in 15-mm dishes were incubated at room temperature for 90 min with 500 µl of 5 nM nAgrin-AP, mAgrin-AP or AP. Cells were washed three times with the HABH buffer (0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.1% NaN3, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 in Hank’s balanced salt solution) and fixed in 60% acetone, 3% formaldehyde in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) for 15 sec. Fixed cells were washed once in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl, incubated at 65°C for 100 min to inactivate endogenous AP, washed again in the AP buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.4/0.1 M NaCl/5 mM MgCl2) and stained at room temperature overnight with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP) (165 µg/ml)/nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) (330 µg/ml) in the AP buffer. Digital photographs of stained cells were analyzed by using the NIH ImageJ software. In some experiments, Agrin-AP-bound cells were lyzed in the lysis buffer (1% Triton-X100, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0). After the inactivation of the endogenous AP, lysates were assayed for AP activity using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) as substrate.

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and AChR clustering assays

These assays were performed as previously described (Luo et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2008). Unless otherwise indicated, the final concentration of recombinant neuronal agrin was 1 nM to stimulate muscle cells. Band intensity of immunoblot was analyzed by using the ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

Data of multiple groups was analyzed by ANOVA, followed by a student-Newman-Keuls test. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare data between two groups. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Values and error bars in figures denote mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Zach Hall for original constructs of agrin and MuSK, Dr. Xi He for Wnt, LRP6 and Frizzled constructs, and Dr. Jon Lindstrom and Dr. Rick Rotundo for anti-AChR antibodies. We are grateful to members of the Mei and Xiong laboratories for discussion. This work was support in part by grants from NIH (L.M. and W.C.X) and Muscular Dystrophy Association (L.M.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bafico A, Liu G, Yaniv A, Gazit A, Aaronson SA. Novel mechanism of Wnt signalling inhibition mediated by Dickkopf-1 interaction with LRP6/Arrow. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:683–686. doi: 10.1038/35083081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezakova G, Helm JP, Francolini M, Lomo T. Effects of purified recombinant neural and muscle agrin on skeletal muscle fibers in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1441–1452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose CM, Qiu D, Bergamaschi A, Gravante B, Bossi M, Villa A, Rupp F, Malgaroli A. Agrin controls synaptic differentiation in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9086–9095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09086.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowe MA, Deyst KA, Leszyk JD, Fallon JR. Identification and purification of an agrin receptor from torpedo postsynaptic membranes: a heteromeric complex related to the dystroglycans. Neuron (USA) 1994;12:1173–1180. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon EP, Lin W, D'Amour KA, Pizzo DP, Dominguez B, Sugiura Y, Thode S, Ko CP, Thal LJ, Gage FH, Lee KF. Aberrant patterning of neuromuscular synapses in choline acetyltransferase-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:539–549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00539.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Liu YI. Wnt signaling: complexity at the surface. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:395–402. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanelli JT, Gayer GG, Scheller RH. Alternative RNA splicing that determines agrin activity regulates binding to heparin and alpha-dystroglycan. Development. 1996;122:1663–1672. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanelli JT, Roberds SL, Campbell KP, Scheller RH. A role of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins and utrophin in agrin-induced AChR clustering. Cells. 1994;77:663–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheusova T, Khan MA, Schubert SW, Gavin AC, Buchou T, Jacob G, Sticht H, Allende J, Boldyreff B, Brenner HR, Hashemolhosseini S. Casein kinase 2-dependent serine phosphorylation of MuSK regulates acetylcholine receptor aggregation at the neuromuscular junction. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1800–1816. doi: 10.1101/gad.375206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani L, Salinas PC. WNTs in the vertebrate nervous system: from patterning to neuronal connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:351–362. doi: 10.1038/nrn1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NA, Kaufmann WE, Worley PF, Rupp F. Expression of agrin in the developing and adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 1997;76:581–596. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara TM, Bowen DC, Valenzuela DM, Simmons MV, Poueymirou WT, Thomas S, Kinetz E, Compton DL, Rojas E, Park JS, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo. Cell. 1996;85:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Xi Y, Chen T, Wang JY, Tao DL, Wu ZL, Li YP, Li C, Zeng R, Li L. Caprin-2 enhances canonical Wnt signaling through regulating LRP5/6 phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:865–872. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferns M, Deiner M, Hall Z. Agrin-induced acetylcholine receptor clustering in mammalian muscle requires tyrosine phosphorylation. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;132:937–944. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.5.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferns MJ, Campanelli JT, Hoch W, Scheller RH, Hall Z. The ability of agrin to cluster AChRs depends on alternative splicing and on cell surface proteoglycans. Neuron (USA) 1993;11:491–502. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90153-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A. Abnormal synapse formation in agrin-depleted hippocampal neurons. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 24):4729–4738. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn AJ, Feng G, Pendergast AM. Postsynaptic requirement for Abl kinases in assembly of the neuromuscular junction. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:717–723. doi: 10.1038/nn1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JG, Cheng HJ. Alkaline phosphatase fusion proteins for molecular characterization and cloning of receptors and their ligands. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:198–210. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu AK, Cheung ZH, Ip NY. Beta-catenin in reverse action. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:244–246. doi: 10.1038/nn0308-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer C, Sugiyama JE, Taylor RG, Hall ZW. Association of muscle-specific kinase MuSK with the acetylcholine receptor in mammalian muscle. Embo J. 1997;16:4951–4960. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam M, Noakes PG, Moscoso L, Rupp F, Scheller RH, Merlie JP, Sanes JR. Defective neuromuscular synaptogenesis in agrin-deficient mutant mice. Cell. 1996;85:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee SH, Montanaro F, Lindenbaum MH, Carbonetto S. Dystroglycan-α, a dystrophin-associated glycoprotein, is a functional agrin receptor. Cells. 1994;77:675–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesemann M, Cavalli V, Denzer AJ, Brancaccio A, Schumacher B, Ruegg MA. Alternative splicing of agrin alters its binding to heparin, dystroglycan, and the putative agrin receptor. Neuron (USA) 1996;16:755–767. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesemann M, Denzer AJ, Ruegg MA. Acetylcholine receptor-aggregating activity of agrin isoforms and mapping of the active site. Journal of Cell Biology. 1995;128:625–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DJ, Apel ED, Shah S, Bowen DC, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Sanes JR, Yancopoulos GD. Kinase domain of the muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase (MuSK) is sufficient for phosphorylation but not clustering of acetylcholine receptors: required role for the MuSK ectodomain? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8848–8853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DJ, Bowen DC, Stitt TN, Radziejewski C, Bruno J, Ryan TE, Gies DR, Shah S, Mattsson K, Burden SJ, et al. Agrin acts via a MuSK receptor complex. Cell. 1996a;85:513–523. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DJ, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, DiStefano PS, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD. The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation and is a functional receptor for agrin. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1996b;61:435–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AC, Lucas FR, Salinas PC. Axonal remodeling and synaptic differentiation in the cerebellum is regulated by WNT-7a signaling. Cell. 2000;100:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Semenov M, Tamai K, Zeng X. LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development. 2004;131:1663–1677. doi: 10.1242/dev.01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst R, Burden SJ. The juxtamembrane region of MuSK has a critical role in agrin-mediated signaling. Embo J. 2000;19:67–77. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J, Bock HH. LIPOPROTEIN RECEPTORS IN THE NERVOUS SYSTEM. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2002;71:405–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesser BA, Henschel O, Witzemann V. Synapse disassembly and formation of new synapses in postnatal muscle upon conditional inactivation of MuSK. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenberg LG, Ho KD, Lee D, O'Dowd DK, Smith MA. Agrin regulates neuronal responses to excitatory neurotransmitters in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;19:97–110. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenberg LG, Su H, Gu H, O'Dowd DK, Smith MA. Alpha3Na+/K+-ATPase is a neuronal receptor for agrin. Cell. 2006;125:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf C, Hoch W. Agrin binding to alpha-dystroglycan. Domains of agrin necessary to induce acetylcholine receptor clustering are overlapping but not identical to the alpha-dystroglycan-binding region. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:5231–5236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip FC, Glass DG, Gies DR, Cheung J, Lai KO, Fu AK, Yancopoulos GD, Ip NY. Cloning and characterization of muscle-specific kinase in chicken. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:661–673. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings CGB, Dyer SM, Burden SJ. Muscle-specific trk-related receptor with a kringle domain defines a distinct class of receptor tyrosine kinases. Proceeding of National Academy of Science, USA. 1993;90:2895–2899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EB, Hammer RE, Herz J. Abnormal development of the apical ectodermal ridge and polysyndactyly in Megf7-deficient mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3523–3538. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Meier T, Lichtsteiner M, Witzemann V, Sakmann B, Brenner HR. Induction by agrin of ectopic and functional postsynaptic-like membrane in innervated muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2654–2659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N, Burden SJ. MuSK controls where motor axons grow and form synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:19–27. doi: 10.1038/nn2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen MP, Shen K. Wnt signaling positions neuromuscular connectivity by inhibiting synapse formation in C. elegans. Cell. 2007;130:704–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XM, Dong XP, Luo SW, Zhang B, Lee DH, Ting AK, Neiswender H, Kim CH, Carpenter-Hyland E, Gao TM, et al. Retrograde regulation of motoneuron differentiation by muscle beta-catenin. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:262–268. doi: 10.1038/nn2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Burgess RW, Dominguez B, Pfaff SL, Sanes JR, Lee KF. Distinct roles of nerve and muscle in postsynaptic differentiation of the neuromuscular synapse. Nature. 2001;410:1057–1064. doi: 10.1038/35074025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Tian QB, Endo S, Suzuki T. A role for LRP4 in neuronal cell viability is related to apoE-binding. Brain Res. 2007;1177:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z, Wang Q, Zhou J, Wang J, Liu M, He X, Wynshaw-Boris A, Xiong W, Lu B, Mei L. Regulation of AChR Clustering by Dishevelled Interacting with MuSK and PAK1. Neuron. 2002;35:489–505. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZG, Je HS, Wang Q, Yang F, Dobbins GC, Yang ZH, Xiong WC, Lu B, Mei L. Implication of geranylgeranyltransferase I in synapse formation. Neuron. 2003;40:703–717. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00695-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malbon CC, Wang HY. Dishevelled: a mobile scaffold catalyzing development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2006;72:153–166. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)72002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann S, Kroger S. Agrin is synthesized by retinal cells and colocalizes with gephyrin. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;8:1–13. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0039. [corrected] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. LDL-receptor-related protein 6 is a receptor for Dickkopf proteins. Nature. 2001;411:321–325. doi: 10.1038/35077108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew D, Ataman B, Chen J, Zhang Y, Cumberledge S, Budnik V. Wingless signaling at synapses is through cleavage and nuclear import of receptor DFrizzled2. Science. 2005;310:1344–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.1117051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahan UJ. The agrin hypothesis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1990;55:407–418. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1990.055.01.041. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittaud P, Marangi PA, Erb-Vogtli S, Fuhrer C. Agrin-induced activation of acetylcholine receptor-bound Src family kinases requires Rapsyn and correlates with acetylcholine receptor clustering. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14505–14513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed AS, Rivas-Plata KA, Kraas JR, Saleh SM, Swope SL. Src-class kinases act within the agrin/MuSK pathway to regulate acetylcholine receptor phosphorylation, cytoskeletal anchoring, and clustering. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3806–3818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03806.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M, Nakajima D, Nagase T, Nomura N, Seki N, Ohara O. Identification of High-Molecular-Weight Proteins with Multiple EGF-like Motifs by Motif-Trap Screening. Genomics. 1998;51:27–34. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor LT, Lauterborn JC, Gall CM, Smith MA. Localization and alternative splicing of agrin mRNA in adult rat brain: transcripts encoding isoforms that aggregate acetylcholine receptors are not restricted to cholinergic regions. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:1141–1152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01141.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermoeller-McCormick LM, Li Y, Osaka H, FitzGerald DJ, Schwartz AL, Bu G. Dissection of receptor folding and ligand-binding property with functional minireceptors of LDL receptor-related protein. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:899–908. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Inoue A, Okada M, Murata Y, Kakuta S, Jigami T, Kubo S, Shiraishi H, Eguchi K, Motomura M, et al. The muscle protein Dok-7 is essential for neuromuscular synaptogenesis. Science. 2006;312:1802–1805. doi: 10.1126/science.1127142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard M, Koo ES, Gorczyca M, Sharpe J, Cumberledge S, Budnik V. The Drosophila Wnt, wingless, provides an essential signal for pre- and postsynaptic differentiation. Cell. 2002;111:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01047-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Huganir RL. Comparison of innervation and agrin induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the acetylcholine receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:6834–6841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06834.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reist NE, Werle MJ, McMahan UJ. Agrin released by motor neurons induces the aggregation of acetylcholine receptors at neuromuscular junctions. Neuron (USA) 1992;8:865–868. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90200-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Development of the vetebrate neuromuscular junction. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1999;22:389–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:791–805. doi: 10.1038/35097557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte G, Bryja V. The Frizzled family of unconventional G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenov MV, Tamai K, Brott BK, Kuhl M, Sokol S, He X. Head inducer Dickkopf-1 is a ligand for Wnt coreceptor LRP6. Curr Biol. 2001;11:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si J, Luo Z, Mei L. Induction of acetylcholine receptor gene expression by ARIA requires activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:19752–19759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Chazottes D, Tutois S, Kuehn M, Evans M, Bourgade F, Cook S, Davisson MT, Guenet JL. Mutations in the gene encoding the low-density lipoprotein receptor LRP4 cause abnormal limb development in the mouse. Genomics. 2006;87:673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strochlic L, Cartaud A, Cartaud J. The synaptic muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) complex: new partners, new functions. Bioessays. 2005;27:1129–1135. doi: 10.1002/bies.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama J, Bowen DC, Hall ZW. Dystroglycan binds nerve and muscle agrin. Neuron (USA) 1994;13:103–115. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407:530–535. doi: 10.1038/35035117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian QB, Suzuki T, Yamauchi T, Sakagami H, Yoshimura Y, Miyazawa S, Nakayama K, Saitoh F, Zhang JP, Lu Y, et al. Interaction of LDL receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) with postsynaptic scaffold proteins via its C-terminal PDZ domain-binding motif, and its regulation by Ca/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2864–2876. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela DM, Stitt TN, DiStefano PS, Rojas E, Mattsson K, Compton DL, Nunez L, Park JS, Stark JL, Gies DR, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase specific for the skeletal muscle lineage: expression in embryonic muscle, at the neuromuscular junction, and after injury. Neuron (USA) 1995;15:573–584. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BG. The mechanism of agrin-induced acetylcholine receptor aggregation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Biol. 1991;331:273–280. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1991.0016. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jing Z, Zhang L, Zhou G, Braun J, Yao Y, Wang ZZ. Regulation of acetylcholine receptor clustering by the tumor suppressor APC. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1017–1018. doi: 10.1038/nn1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhang B, Wang YE, Xiong WC, Mei L. The Ig1/2 domain of MuSK binds to muscle surface and is involved in acetylcholine receptor clustering. Neurosignals. 2008;16:246–253. doi: 10.1159/000111567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherbee SD, Anderson KV, Niswander LA. LDL-receptor-related protein 4 is crucial for formation of the neuromuscular junction. Development. 2006;133:4993–5000. doi: 10.1242/dev.02696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston C, Gordon C, Teressa G, Hod E, Ren XD, Prives J. Cooperative regulation by Rac and Rho of agrin-induced acetylcholine receptor clustering in muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6450–6455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston C, Yee B, Hod E, Prives J. Agrin-induced Acetylcholine Receptor Clustering Is Mediated by the Small Guanosine Triphosphatases Rac and Cdc42. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;150:205–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi YL, Tanaka SS, Kasa M, Yasuda K, Tam PP, Matsui Y. Expression of low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (Lrp4) gene in the mouse germ cells. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Arber S, William C, Li L, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Birchmeier C, Burden SJ. Patterning of muscle acetylcholine receptor gene expression in the absence of motor innervation. Neuron. 2001;30:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Luo S, Dong XP, Zhang X, Liu C, Luo Z, Xiong WC, Mei L. Beta-catenin regulates acetylcholine receptor clustering in muscle cells through interaction with rapsyn. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3968–3973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4691-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD, Sanes JR. Distinct domains of MuSK mediate its abilities to induce and to associate with postsynaptic specializations. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1133–1146. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D, Yang Z, Luo Z, Luo S, Xiong WC, Mei L. Muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase endocytosis in acetylcholine receptor clustering in response to agrin. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1688–1696. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4130-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.