Abstract

We searched for deletions in the germline genome among 498 aggressive prostate cancer cases and 494 controls from a population-based study in Sweden (CAPS) using Affymetrix SNP arrays. By comparing allele intensities of ∼500,000 SNP probes across the genome, a germline deletion at 2p24.3 was observed to be significantly more common in cases (12.63%) than in controls (8.28%), P=0.028. To confirm the association, we genotyped this germline copy number variation (CNV) in additional subjects from CAPS and from Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH). Overall, among 4,314 cases and 2,176 controls examined, the CNV was significantly associated with prostate cancer risk (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.06-1.48, P = 0.009). More importantly, the association was stronger for aggressive prostate cancer (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.08-1.58, P = 0.006) than for non-aggressive prostate cancer (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.98-1.45, P = 0.08). The biologic impact of this germline CNV is unknown as no known gene resides in the deletion. Results from this study represent the first novel germline CNV that was identified from a genome-wide search and was significantly, but moderately associated with prostate cancer risk. Additional confirmation of this association and functional studies are warranted.

Keywords: Germline, CNVs, deletion, prostate cancer, association, aggressive

Introduction

A consistent finding of genetic susceptibility to prostate cancer suggests that there are altered germline DNA sequences that affect the function and/or expression of specific genes. These germline alterations include single nucleotide substitutions (SNPs), and deletions/gains of a string of nucleotides such as copy number variations (CNVs). While the importance of SNPs and their associations with disease risk are well established, there is an increasing appreciation for a potential role of CNVs in disease risk (1-6). CNVs are found to be common in the genome; however, their associations with risk of common diseases are under-studied. This gap is largely due to a lack of high-throughput and cost effective methods for detecting germline CNVs in the genome and for genotyping target CNVs in large numbers of cases and controls.

In this study, we report association findings of prostate cancer risk with a common germline CNV at 2p24.3, detected from a genome-wide analysis and confirmed using a simple PCR method among a large number of prostate cancer patients and control subjects from Sweden and the U.S.

Methods

Study subjects

Subjects in the discovery stage of a genome-wide association study

Subjects were a subset of men from CAPS (CAncer of the prostate in Sweden), a population-based case-control study in Sweden (7-8). Prostate cancer patients were identified and recruited from four of the six regional cancer registries in Sweden. These case subjects were classified as having aggressive disease if they met any of the following criteria: T3/4, N+, M+, Gleason score sum ≥ 8, or PSA > 50 ng/ml; otherwise, they were classified as non-aggressive disease. Control subjects were recruited concurrently with case subjects. We selected 498 aggressive prostate cancer cases and 494 unaffected controls matching the age distribution of cases for the discovery stage of genome-wide association study.

Subjects in the confirmation stage

Two study populations were included for the confirmation stage. The first were the remaining subjects from CAPS, including 733 aggressive cases, 1,619 non-aggressive cases, and 1,287 controls from Sweden. The second study population was a hospital-based prostate cancer case-control study of European Americans from Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) (9). It included 1,527 cases and 482 controls of European descent (by self report). We defined more aggressive and less aggressive disease based on tumor stage and Gleason score. Tumors with a Gleason score of 7 or higher or stage pT3 or higher or N+ or M1 (i.e., either high-grade or non—organ-confined disease) were defined as more aggressive. Tumors with a Gleason score of 6 or lower and stage pT2/N0 (i.e., cancer confined to the prostate) were defined as less aggressive. The study received institutional approval and complied with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations. The study received institutional approval.

Genotyping of germline CNVs

Detection of germline deletions in the genome

Germline CNVs were inferred from SNP intensity data of the Affymetrix 500K SNP arrays among 498 aggressive prostate cancer cases and 494 controls of CAPS (8). The dChipSNP computer software was used to estimate DNA copy number from allele intensity for each of the ∼500,000 SNPs (10). We used the following criteria to define a germline deletion: 1) DNA copy number ≤ 1.5 and ≤ 0.5 for a hemizygous and homozygous deletion, respectively, 2) a homozygous genotype (expected in a hemizygous deletion) or no genotype call (expected in a homozygous deletion), and 3) must involve at least three consecutive SNPs with a minimum physical length of 1 kb. We focused on germline deletions only in this study because SNP information can be used to improve the quality of defining deletions.

Confirmation of germline deletions using quantitative PCR

Three subjects with the deletion and one subject without the deletion at 2p24.3 were selected for independent confirmation by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (11).

Mapping breakpoints of the germline deletion at 2p24.3

Subjects who were inferred to have the germline deletion at 2p24.3 (N = 100) were selected for the breakpoint analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). Based on the putative breakpoints deduced from the allele intensity of the SNP probes of Affymetrix 500K SNP arrays, PCR primers were designed based on the flanking genomic sequence of the target CNV. We then sequenced the PCR products using dye-terminator chemistry (BigDye, ABI, Foster City, CA) and determined the exact breakpoints.

Measurement of germline deletion at 2p24.3

We used a regular PCR method to measure the germline 2p24.3 deletion among all cases and controls from CAPS and JHH. Deleted and wild-type genotypes at the CNV can be detected simultaneously based on the different lengths of PCR products. The primer set is available upon request. The same PCR conditions were used as described above.

Statistical analysis

Tests for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) were performed separately among case patients and control subjects using Fisher’s exact test. Haplotype blocks were estimated using a computer program Haploview (12), and a default Gabriel method(13) was used to define a haplotype block. Differences in the carrier frequencies of the deletion between case patients and control subjects were tested using a chi-square test with 1 degree of freedom (two-sided). Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated using an unconditional logistic regression with adjustment for age and geographic region (for CAPS only).

Results and Discussion

We identified 1,740 deletions in the genome that have a frequency of > 1 % in 498 prostate cancer cases and 494 controls. We then compared the frequencies of these deletions in cases and controls (Supplementary Figure 2) and identified 76 unique putative deleted regions that were associated with prostate cancer risk (P < 0.05). To reduce the measurement errors in defining DNA copy numbers and to identify a subset of putative deletions with high confidence to be true CNVs, we examined the distributions of DNA copy numbers among the subjects. This second step identified seven independent regions where three groups of subjects carrying 2, 1, and 0 copies were distinguishable with high confidence. To rule out artifactual copy number changes due to technical issues (e.g. mutations in restriction enzyme sites of Sty or Nsp used in the Affymetrix SNP array protocol can lead to reduced DNA copy number) we developed a qPCR assay as an independent molecular method to further confirm the deletions. One region at 2p24.3 was selected for a qPCR analysis because it was the only deletion that had frequency greater than 5% in the controls. The concordance in detecting the germline deletion using the SNP array and the qPCR analysis was 100% in three subjects with the deletion and one subject without the deletion. Among the subjects in the GWAS whose DNA copy number could be reliably determined, the deletion was found in 60 of 475 cases (12.63%) and 40 of 483 controls (8.28%). The difference was statistically significantly, with a nominal P of 0.028.

This germline deletion at 2p24.3 involves six consecutive SNPs in the Affymetrix 500K SNP arrays (one on Nsp and five on Sty arrays) and spans 3,670 bp between rs16861868 (14,656,949 bp) and rs2380618 (14,660,690) (Fig 1a). It overlaps with a known CNV region [locus 166 of the Database of Genomic Variants (2) and CNP119 of the UCSC Genome Browser on Human May 2004 Assembly] (14-16). However, the reported frequencies from these studies, ranging from 0.1% to 6%, are considerably lower than what we observed in our study. This discrepancy could be due to different genotyping platforms and the criteria used to define CNV in different studies, as well as geographic differences of study subjects (17). It is also interesting to note that none of the six SNPs was associated with prostate cancer risk (P > 0.05) in the subjects of our CAPS GWAS study.

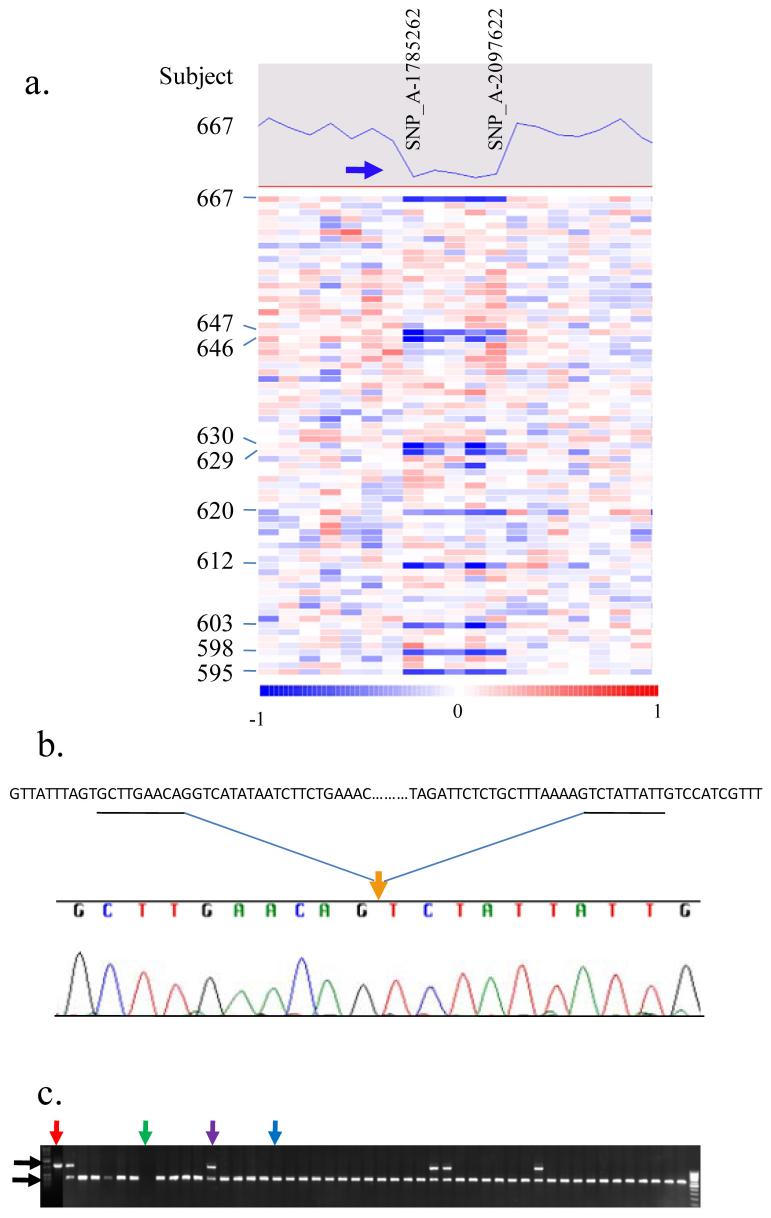

Figure 1.

Detection of a germline deletion at chromosome 2p24.3. 1a, Examples of results from Affymetrix 500K SNP arrays (only Sty array is shown). Allele intensity data of a number of SNPs at 22p24.3 for subject 667 are shown at the top. A heat map of these SNPs generated using dChip for subject 667 and other subjects is shown below. Evidence for a deletion involving five consecutive SNPs is observed (blue bars) in multiple subjects. 1b, An example DNA sequence illustrates the location of the 5,947 bp deletion (orange arrow) that occurs in all 80 samples examined. 1c, Gel electrophoresis displays PCR fragments representing the deletion (1,136 bp, top, black arrow) and the wild type (590 bp, bottom, black arrow) of this CNV locus. Red, purple, and blue arrows indicate subjects with the homozygous deletion, hemizygous deletion, and homozygous wildtype, respectively. A green arrow indicates the negative control.

To map the deletion boundaries, we designed a set of PCR primers flanking the putative breakpoints deduced from the allele intensity of the SNP probes of Affymetrix 500K SNP arrays. Genomic DNA samples from 100 subjects who carried the deletion CNV were amplified using these PCR primers and the resulting fragments were directly sequenced. We found that all 100 subjects carried the same 5,947 bp nucleotide deletion between 14,662,627 bp and 14,668,573 bp (Fig 1b). Because of the uniform boundaries of the CNV, we were able to design a single set of primers to amplify two possible different lengths of PCR fragments, one representing the deleted allele and the other representing the wild-type (non-deleted) allele, in a single reaction to identify DNA samples with homozygous deletion, hemizygous deletion, or no deletion (marked by red, purple, and blue arrows, respectively, in Fig 1c).

We then used this PCR method to genotype this germline deletion among the remaining subjects from CAPS (2,386 cases and 1,213 controls) and all study subjects from JHH (1,453 cases and 480 controls). Within the CAPS and JHH study populations, the germline deletion was in HWE among controls and cases respectively (P ≥ 0.05). While the germline deletion was higher in both sets of cases than in controls, the difference was only statistically significant in the JHH population (P = 0.03, two-sided) (Table 1). When all 4,314 cases and 2,176 controls were examined, the deletion was significantly associated with prostate cancer risk (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.06-1.48, P = 0.009). Importantly, a stronger association of the germline deletion with prostate cancer risk was found among aggressive cases (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.08-1.58, P = 0.006) than among non-aggressive cases (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.98-1.45, P = 0.08) in the combined data from CAPS and JHH. However, the difference in ORs was not statistically significant (P = 0.33).

Table 1.

Frequencies of germline CNP at 2p24.3 in prostate cancer cases and controls

| Association test |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases |

Controls |

% of deletion carrier |

|||||||

| WW | WD | DD | WW | WD | DD | Cases | Controls | P-value | |

| All cases | |||||||||

| CAPS-GWAS | 415 | 56 | 4 | 443 | 39 | 1 | 12.63% | 8.28% | 0.03 |

| Remaining CAPS | 2103 | 276 | 7 | 1078 | 129 | 6 | 11.86% | 11.13% | 0.52 |

| JHH | 1278 | 169 | 6 | 441 | 37 | 2 | 12.04% | 8.13% | 0.02 |

| Total | 3796 | 501 | 17 | 1962 | 205 | 9 | 12.01% | 9.83% | 0.009 |

| Aggressive cases | |||||||||

| CAPS-GWAS | 415 | 56 | 4 | 443 | 39 | 1 | 12.92% | 8.28% | 0.03 |

| Remaining CAPS | 647 | 95 | 1 | 1078 | 129 | 6 | 12.88% | 11.13% | 0.23 |

| JHH | 849 | 110 | 6 | 441 | 37 | 2 | 12.02% | 8.13% | 0.02 |

| Total | 1911 | 261 | 11 | 1962 | 205 | 9 | 12.46% | 9.83% | 0.006 |

| Non-aggressive cases | |||||||||

| CAPS-GWAS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 443 | 39 | 1 | -- | 8.28% | -- |

| Remaining CAPS | 1456 | 181 | 6 | 1078 | 129 | 6 | 11.38% | 11.13% | 0.83 |

| JHH | 415 | 56 | 0 | 441 | 37 | 2 | 11.89% | 8.13% | 0.05 |

| Total | 1871 | 237 | 6 | 1962 | 205 | 9 | 11.49% | 9.83% | 0.08 |

The functional impact of this CNV is not clear as no known gene resides in the ∼6kb deletion. However, there are only two genes, AY928977 and FAM84A, located within 100kb of this CNV. AY928977 is a spliced fusion transcript between the first 14 exons of the anthrax toxin receptor I gene (ANTX1) and novel neuroblastoma gene 1 (NNG1) (18). However, the ANTX1-NNG1 fusion transcript is less likely to play an essential role in carcinogenesis dues to its limited expression in only one neuroblastoma cell line and its sublines, but not in 70 primary neuroblastoma tumors (18). FAM84A is a component of extracellular matrices (EMC) and has been found to be up-regulated in several tumors (19), including prostate cancers. Notably, exogenous FAM84A expression was found to increase cell motility in NIH3T3 cells and may contribute to metastasis (19). The impact of this CNV on the expression of FAM84A is unclear since it is not within the proximal regulatory promoter of FAM84A. However, it is likely that uncharacterized distal regulatory elements that either activate or suppress FAM84A expression exist within this CNV. Additionally, the existence of yet identified small regulatory RNAs in this CNV is another testable hypothesis. Therefore, despite the lack of direct functional evidence of the involvement of this CNV, there remains the potential for this CNV to impact prostate carcinogenesis.

Although we report one of the first germline CNVs associated with prostate cancer risk in general populations, we acknowledge this study has several important limitations. First, the overall statistical evidence for the prostate cancer association is moderate. Therefore, it remains possible that the association finding is due to chance alone. Second, the observed association results could be affected by measurement error because the PCR method used to measure the germline deletion has not been extensively evaluated. However, when measuring the germline deletion, we observed an excellent concordance rate (98%) between the PCR method and Affymetrix SNP arrays among ∼1,000 subjects, providing some assurance. Finally, our study on global germline CNVs is incomplete because only a small fraction of germline deletions in the genome were systematically evaluated among a small number of case and control subjects. Additional genome-wide studies on germline CNVs using higher-resolution SNP arrays among a large number of cases and controls are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study is supported by National Cancer Institute CA129684, CA105055, CA106523, and CA95052 to J.X., CA112517 and CA58236 to W.B.I., Department of Defense grant PC051264 to J.X, Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden) to HG and Swedish Academy of Sciences (Vetenskapsrådet) to HG.

The authors thank all the study subjects who participated in the CAPS study and urologists who included their patients in the CAPS study. We acknowledge the contribution of multiple physicians and researchers in designing and recruiting study subjects, including Dr. Hans-Olov Adami (for CAPS) and Drs. Bruce J. Trock, Alan W. Partin, and Patrick C. Walsh (for JHH).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Troge J, et al. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004;305:525–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:949–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–54. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuzun E, Sharp AJ, Bailey JA, et al. Fine-scale structural variation of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:727–32. doi: 10.1038/ng1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrad DF, Andrews TD, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Pritchard JK. High-resolution survey of deletion polymorphism in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:75–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarroll A, Hadnott TN, Perry GH, et al. Common deletion polymorphisms in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:86–92. doi: 10.1038/ng1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng SL, Augustsson-Balter K, Chang B, et al. Sequence variants of toll-like receptor 4 are associated with prostate cancer risk: results from the CAncer Prostate in Sweden Study. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2918–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duggan D, Zheng SL, Knowlton M, et al. Two genome-wide association studies of aggressive prostate cancer implicate putative prostate tumor suppressor gene DAB2IP. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1836–44. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng SL, Sun J, Cheng Y, et al. Association between two unlinked loci at 8q24 and prostate cancer risk among European Americans. JNCI. 2007;99:1525–33. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin M, Wei LJ, Sellers WR, Lieberfarb M, Wong WH, Li C. dChipSNP: significance curve and clustering of SNP-array-based loss-of-heterozygosity data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1233–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W, Chang BL, Li T, et al. Germline copy number polymorphisms involving larger than 100 kb are uncommon in normal subjects. Prostate. 2007;67:227–33. doi: 10.1002/pros.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Smith AJ, Tsalenko A, Sampas N, et al. Array CGH analysis of copy number variation identifies 1284 new genes variant in healthy white males: Implications for association studies of complex diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2783–94. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto D, Marshall C, Feuk L, Scherer SW. Copy-number variation in control population cohorts. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:R168–73. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, et al. PennCNV: An integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17:1665–74. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidd JM, Newman TL, Tuzun E, Kaul R, Eichler EE. Population stratification of a common APOBEC gene deletion polymorphism. PLoS Genet. 2007;20:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberthuer A, Skowron M, Spitz R, et al. Characterization of a complex genomic alteration on chromosome 2p that leads to four alternatively spliced fusion transcripts in the neuroblastoma cell lines IMR-5, IMR-5/75 and IMR-32. Gene. 2005;363:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi T, Masaki T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Furukawa Y, Nakamura Y. A gene encoding a family with sequence similarity 84, member A (FAM84A) enhanced migration of human colon cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.