Abstract

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) join amino acids to their cognate tRNAs to initiate protein synthesis. Class II ARS possess a unique catalytic domain fold, possess active site signature sequences, and are dimers or tetramers. The dimeric class I enzymes, notably TyrRS, exhibit half-of-sites reactivity, but its mechanistic basis is unclear. In class II histidyl-tRNA synthetase (HisRS), amino acid activation occurs at different rates in the two active sites when tRNA is absent, but half-of-sites reactivity has not been observed. To investigate the mechanistic basis of the asymmetry, and explore the relationship between adenylate formation and conformational events in HisRS, a fluorescently labeled version of the enzyme was developed by conjugating 7-diethylamino-3-((((2-maleimidyl)ethyl)amino)carbonyl)coumarin (MDCC) to a cysteine introduced at residue 212, located in the insertion domain. The binding of the substrates histidine, ATP, and 5′-O-[N-(l-histidyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine to MDCC-HisRS produced fluorescence quenches on the order of 6–15%, allowing equilibrium dissociation constants to be measured. The rates of adenylate formation measured by rapid quench and domain closure as measured by stopped-flow fluorescence were similar and asymmetric with respect to the two active sites of the dimer, indicating that conformational change may be rate-limiting for product formation. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer experiments employing differential labeling of the two monomers in the dimer suggested that rigid body rotation of the insertion domain accompanies adenylate formation. The results support an alternating site model for catalysis in HisRS that may prove to be common to other class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.

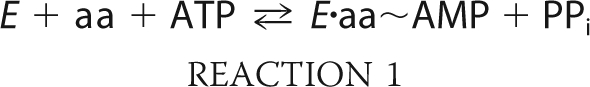

The aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs)2 comprise two distinct classes of enzymes, all of which catalyze a two-step reaction to generate aminoacyl-tRNA for protein synthesis (1, 2) (Reactions 1 and 2).

|

|

During the first of two partial reactions in aminoacylation, the cognate amino acid is condensed with ATP to form an aminoacyl-adenylate. This half reaction proceeds by an associative mechanism in which the stereochemistry of the α-phosphate undergoes inversion (3). The adenylate then undergoes a subsequent attack by the cognate tRNA, with the amino acid undergoing transfer to the 3′-terminal adenosine. Aminoacyl transfer requires the activation of 2′ or 3′ of the terminal hydroxyl, and its rate may be accelerated by a number of different mechanisms, including proton transfer to the adenylate, and proton shuttling to the 2′-OH and then to neighboring active site residues (4, 5). Many ARSs can activate their cognate amino acids in the absence of tRNA, allowing the two partial reactions to be studied individually. Notably, there are significant gaps in our understanding of how the adenylation and aminoacyl transfer half reactions are integrated into the overall reaction schemes of ARSs.

Class I and class II enzymes can be broadly distinguished by their oligomeric structure. The former are generally monomeric, whereas the latter are typically dimeric or tetrameric (6). Notable exceptions to this pattern are the class Ic tyrosyl- and tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetases, both of which form obligatory dimers (7, 8). Both have been described as possessing half-of-sites reactivity (9, 10), but the picture is more complex. Consistent with half-of-sites reactivity, TyrRS binds one mole of tyrosine per dimer and retains a single mole of adenylate per mole of dimers when the E·Ade complex is purified away from unreacted substrates by size-exclusion chromatography (11). However, the steady-state kinetics of TyrRS show no evidence of cooperativity, the second binding site becomes accessible to substrates when the first site is occupied by adenylate, and TyrRS clearly binds 2 mol of tRNA in the crystal (7, 12).

On the basis of these and other observations involving the rate of hydrolysis of the on-enzyme adenylate, Fersht (13) proposed that the second site of TyrRS possesses weak catalytic activity and that TyrRS is asymmetric in solution. The impact of this potential asymmetry in the activation reaction on the complete TyrRS catalytic cycle remains to be explored. TrpRS also exhibits half-of-sites reactivity, and a detailed analysis of the aminoacyl transfer reaction by pre-steady state kinetics proposed both random and ordered versions of alternating site catalysis as models of the enzyme (14). In the class II ARSs, the tetrameric SepRS represents the single example where half-of-sites reactivity has been demonstrated experimentally (15).

Despite this apparent class distinction, recent work on HisRS, a class IIa ARS that is well characterized with respect to structure (16–19), tRNA recognition, and reaction kinetics (4, 20), highlighted several functional attributes that are reminiscent of class I TyrRS. Like TyrRS, HisRS retains only 1 mol of adenylate per dimer when subjected to size-exclusion chromatography (4). A detailed pre-steady-state analysis of mutants of tRNAHis or HisRS compromised with respect to tRNA identity suggested that, in the complete aminoacylation reaction, formation of aminoacyl adenylate in the second active site is contingent upon a productive aminoacyl transfer reaction in the first (20). These and other data led to the proposal of an alternating site model for HisRS (20) that is analogous to the “flip flop” catalysis suggested for class II PheRS (21, 22) and class Ic TrpRS (14). This raises the possibility that the catalytic cycles of dimeric class II enzymes and dimeric class Ic enzymes share some common feature.

Alternating catalysis requires a mechanism for coupling events between active sites, presumably through conformational changes propagated between these active sites. To investigate these events, a version of HisRS was developed that featured the site-specific incorporation of extrinsic environmentally sensitive fluorescent probes, allowing the adenylation reaction to be followed by stopped-flow fluorometry. Comparison of the kinetics of substrate-induced fluorescence changes to the kinetics of product formation determined by rapid quench suggests that adenylation rates are asymmetric with respect to the two active sites of the dimer, and that conformational changes linked to the insertion domain may be rate-limiting for product formation. The implications of these results for a previous model (20) of alternating site catalysis in HisRS are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General Chemicals and Reagents

Unless otherwise noted, chemicals were provided by Fisher Scientific and Sigma. HEPES “ultra pure” from Calbiochem was used in fluorescence experiments to reduce background fluorescence. Restriction endonucleases and enzymes for molecular biology were obtained from New England Biolabs. The maleimide-conjugated versions of AlexaFluor 488 (AF488), QSY-7, and 7-diethylamino-3-((((2-maleimidyl)ethyl)amino)carbonyl)coumarin (MDCC) were obtained from Invitrogen. The 5′-O-[N-(l-histidyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine (HSA) was purchased from RNA-TEC (Leuven, Belgium). Oligonucleotides for site-directed mutagenesis were purchased from Operon Technologies. Radioactive stocks were purchased from Amersham Biosciences, whereas nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography resin was purchased from Qiagen. All solutions were prepared in autoclaved Milli Q water ultrafiltered through a 0.45-μm filter (Millipore).

Construction of Extrinsically Labeled HisRS Variants

The wild-type hisS gene encodes five cysteines, at positions 88, 130, 196, 241, and 283 (23). A subset of these (88, 196, and 241) is labeled by maleimide-linked fluorescence probes (data not shown). Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was employed to substitute readily labeled cysteines with functionally benign amino acid replacements, employing structural information and alignments with other HisRS orthologs to guide the choice of substitutions. Starting with pWY30 (24), a pQE30 derivative that encodes the gene for Escherichia coli histidyl-tRNA synthetase, QuikChange mutagenesis was used in a serial fashion to substitute Cys-88 with valine, Cys-196 with serine, and Cys-241 with leucine. The resulting “Cys-lite” variant of HisRS (denoted herein as clHisRS) carries all three substitutions (C88V, C196S, and C241L) and could not be labeled with maleimide probes. To generate versions of clHisRS useful as fluorescently labeled reporter proteins, additional cysteines were introduced at solvent-accessible positions proximal to substrate binding sites on the enzyme, producing the mutant proteins N212C clHisRS, L276C clHisRS, N368C clHisRS, and L402C clHisRS. The sequences of all the resulting mutant plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing. For experiments that employed labeled HisRS heterodimers, a version of N212C clHisRS was constructed using QuikChange in a plasmid background that does not encode a His6 affinity tag. To assess the functional consequences of these substitutions, steady-state pyrophosphate exchange and aminoacylation assays were performed (25). The final constructs in the clHisRS background were also evaluated for their ability to report on substrate binding and/or chemistry by virtue of induced fluorescence changes.

Preparation of Protein and tRNA Stocks

His6-tagged wild type, and His6-tagged N212C clHisRS HisRS were prepared as described previously (4, 20, 24) with only minor variations. Untagged wild-type and N212C clHisRS were purified as described previously (26), employing Q-Sepharose and hydroxyapatite chromatography. Individual fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and fractions judged to be greater than 99% pure were pooled and dialyzed at 4 °C into Buffer A (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol). Following the addition of 50% glycerol, protein stocks were stored at −20 °C until labeling. Yields of 30 mg of purified protein per liter of bacterial cell culture were typically obtained. The in vitro transcribed tRNAHis substrate was prepared from pWY40 as described previously (4, 24, 25). A specific acceptance of 900–1200 pmol of [14C]histidine accepted/A260 absorbance unit was routinely obtained. Aminoacylation assays to test the specific acceptance of the tRNA preparations were performed as described in Ref. 25.

Labeling of N212C-clHisRS

Preparations of N212C clHisRS (containing or lacking the His6-affinity tag) stored in 50% glycerol were dialyzed against Buffer A with 0.1 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride overnight to remove β-mercaptoethanol present in the storage buffer. MDCC (ϵ419 = 50,000 m−1 cm−1) was dissolved in DMSO to a final concentration of 14–16 mm. The labeling was performed according to the manufacturer's directions for 1 h at room temperature under conditions of 10-fold excess of label to monomer, and then terminated by dialyzing protein against the Buffer A with 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol overnight at 4 °C. This procedure was sufficient to remove unbound dye from the preparation. The labeling efficiency was calculated from the ratio of MDCC to HisRS monomer, based on the extinction coefficients for the two species, and taking into account the contribution of the dye to the absorbance at A280,

where Ax = absorbance value of the dye at the absorption maximum wavelength, and ϵ = molar extinction coefficient of the dye or reagent at the absorption maximum wavelength. Labeling efficiencies of >92% were routinely obtained.

Steady-state Fluorescence Measurements

Steady-state measurements were obtained using a QM-6 (Photon Technology International) fluorometer equipped with a 75-watt xenon arc lamp at 25 °C. Samples were excited at 429 nm, and emission was measured between 447 and 487 nm using a 2 nm bandpass filter on the excitation and 4 nm bandpass on the emission channels. In a typical experiment, 1 ml of 100 nm MDCC-conjugated protein in Buffer A was added to a 2-ml stirred-cell quartz fluorometer cuvette (Starna Cells Inc., Atascadero, CA) in a temperature-controlled holder. The titrating substrates were added from concentrated stocks (typically 100 mm), and the final fluorescence values were corrected for dilution. The histidine and ATP titrations were analyzed assuming an excess of substrate relative to the bound fraction, with the fraction bound calculated according to the standard hyperbolic function,

|

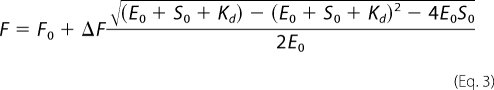

where F is the fraction bound, S is the substrate concentration, and Kd equals the equilibrium dissociation constant. The data from HSA titrations, where [E] > Kd, were fit instead to the following quadratic function,

|

where F0 is the starting fluorescence, ΔF is the total fluorescence change, E0 is the initial concentration of enzyme, and S0 the initial concentration of substrate.

RET Sample Preparation

HisRS heterodimers (N212C clHisRS) conjugated with donor and acceptor fluorophores were generated for resonance energy transfer (RET) experiments. AlexaFluor488 and QSY7-maleimide were chosen as the donor-acceptor pair for the assay based on the predicted distance between the monomer N212 residues. QSY-7, the fluorescence acceptor, absorbs light in the fluorescence range but emits none itself, making it useful for “single color” fluorescence resonance energy transfer experiments. Such chromophores have been referred to colloquially as “black hole quenchers.” The preparation of AF488-conjugated (His6)- clHisRS and QSY-7-conjugated (untagged) clHisRS was accomplished using the procedure described above for MDCC-N212C clHisRS. The doubly conjugated heterodimeric HisRS was prepared by combining AF488:(His6)-N212C clHisRS and QSY-7: (untagged) N212C clHisRS in a 1:4 ratio and then dialyzing for 3 h in Buffer A plus 4 m urea. The urea was slowly removed by sequential dialyzes of ∼3 h each in 3 m urea, 2 m urea, 1 m urea, and 0.5 m urea, followed by three dialyses of at least 4 h each in Buffer A lacking urea. Re-associated heterodimers were isolated from excess untagged homodimer using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography, as described above and previously (27). Although this method does not specifically prevent the formation and capture of His6-tagged homodimers, the excess of unlabeled species present during renaturation biases the resultant mixture heavily in favor of heterodimeric species. Additionally, the His6-tagged species is chosen such that any homodimeric species that are recovered cannot effect the experimental signal (i.e. homodimeric AF488-N212C clHisRS cannot undergo RET). Absorbance wavelength scans were performed to ensure the homogeneity of the heterodimer population and compute the stoichiometry of label incorporation. The stoichiometry was determined by comparing protein (A280 nm, ϵ280 = 127,097) and probe concentrations (AlexaFluor 488: Absmax = 493 nm, ϵ493 = 72,000; and QSY-7: Absmax = 560 nm, ϵ 560 = 92,000) of the final eluted fractions from the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column isolation. The final preparations were checked in aminoacylation assays to assess the effect of the extrinsic probe on ARS function. Additional heterodimers composed of the wild-type and R259H mutant versions of HisRS were constructed by use of the denaturation/renaturation protocol described above for construction of the fluorescent heterodimers. The resulting Wt/R259H heterodimer constructs were characterized by active site titration. Notably, the residual R259H homodimer that might copurify under these conditions is kinetically invisible under the timescale of the assay employed.

Steady-state RET

Emission spectra (500–600 nm) were collected at 20 °C with an excitation wavelength of 460 nm using a Photon Technology International QM-6 fluorometer equipped with a 75-watt xenon arc lamp as an excitation source. Slit widths were 2 nm. Substrate (histidine and/or ATP) was added, and the steady-state measurements were repeated. Control experiments used AF488-conjugated homodimers or substituted histidinol for histidine. Fluorescence emission intensities were normalized to one based on the emission of heterodimer in the absence of substrate. Transfer efficiency, E, was calculated as E = 1 − ΙDA/ΙD, where ΙDA is the intensity of the donor in the presence of acceptor, and ΙD is the intensity of the donor in the absence of acceptor (28).

Pre-steady-state Measurements

Pre-steady-state fluorescence measurements were performed on a SX.18MV stopped-flow spectrofluorometer (Applied Photophysics, Surrey, UK) with 425 nm excitation and 455 nm cutoff filters and a 2 mm bandpass filter on the monochrometer. All reactions were performed at 25 °C in Buffer A. Fluorescence transients were monitored over 20 s, and the results from 4–6 traces of a single concentration in a titration series were averaged before fitting the data numerically. Rapid quench experiments were carried out using an RQF-3 (Kintek) as described previously (4, 20). Active site titrations were performed as described before (25, 29).

Pre-steady-state Data Analysis

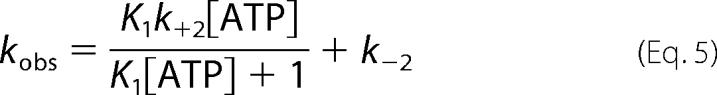

The analysis of ATP titrations of histidinol-saturated MDCC-N212C clHisRS was based on Scheme 1, where E* represents an isomerized state of HisRS with altered fluorescence properties. Based on the lack of an observable fluorescent transient when ATP is titrated against apo-enzyme or enzyme saturated with non-cognate amino acid, the binding of ATP to histidinol-saturated HisRS to form the initial collision complex is presumed to be in rapid equilibrium relative to the subsequent isomerization step (30). Additionally, the dependence of kobs on [ATP] was uniformly described by a hyperbolic function, which is the hallmark of a two-step binding reaction. Progress curves for ATP titrations were fit to a double-exponential function of the following form,

kobs1 and kobs2 were presumed to reflect isomerization events accompanying amino acid activation (see “Discussion”) in active sites 1 and 2 (arbitrary designation) of the HisRS dimer, and were independently fit to the following hyperbolic function.

SCHEME 1.

|

RESULTS

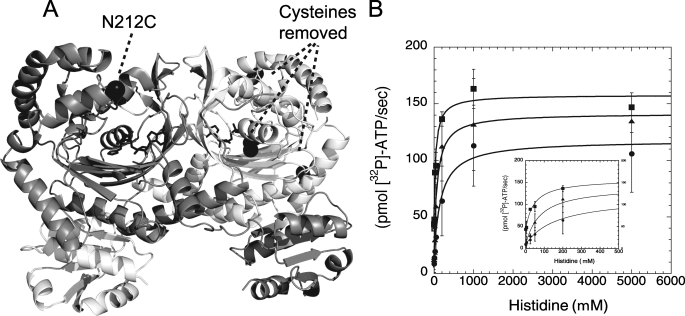

Design of a Modified HisRS Readily Labeled with Fluorescence Probes and Equilibrium Fluorescence Measurements

To investigate the conformational changes within the enzyme active site, an engineered variant of HisRS was generated by site-directed mutagenesis that could be labeled with an extrinsic environmentally sensitive fluorophore at a unique location (Fig. 1A). As described under “Experimental Procedures,” the strategy involved removal by site-directed mutagenesis of cysteines in the native polypeptide that could be readily labeled with maleimide conjugated probes, followed by introduction of new cysteines at positions in proximity to substrates. The most useful variant produced by this approach was N212C clHisRS, where the residue substituted (Asn-212) is located within an α-helical segment in the insertion domain that lies proximal to the HisRS active site (19). By comparison, the other three mutants labeled at stoichiometries substantially below one MDCC dye molecule/polypeptide chain, exhibited minimal fluorescence changes upon substrate binding, or both. These were not characterized further in this study. The activities of unconjugated N212C clHisRS and MDCC-N212C clHisRS were investigated by employing both pyrophosphate exchange and aminoacylation assays. In the pyrophosphate exchange assay, N212C clHisRS and MDCC-N212C clHisRS exhibited modest kcat effects (1.2- and 1.5-fold decreases, respectively), whereas Km (histidine) values showed a marginally greater effect (1.7- and 3.8-fold increases, respectively) (Fig. 1B). In the aminoacylation reaction, by contrast, the effect of the MDCC modification was more significant, decreasing the rate of transfer by 12-fold relative to wild-type enzyme without significantly increasing Km (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Preparation and characterization of the N212C clHisRS reporter system. A, ribbon diagram of E. coli HisRS (pdb: 1KMM). Monomers are colored dark gray and white with histidyl ∼adenylate displayed in both active sites. The white monomer shows mutated cysteines, the dark gray monomer shows introduced cysteine at position 212 (generated in silico). Not shown are L276C, N368C, and L402C. B, pyrophosphate exchange assay for clHisRS and variants, at 37 °C and pH 7.5. Reaction mixtures contained 10 nm enzyme (dimer), 1–5000 μm histidine, 2 mm ATP, 10 mm potassium fluoride, and 2 mm [γ-32P]pyrophosphate in Buffer A. The initial velocity versus substrate curves for wild-type HisRS (■) N212C clHisRS (▴), and MDCC-N212C clHisRS (●) are shown.

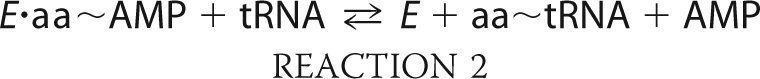

Equilibrium Measurements

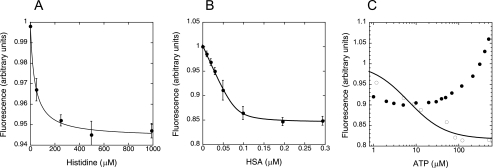

To validate MDCC-N212C clHisRS as a useful reporter of the adenylation reaction, equilibrium fluorescence studies were performed. The results of these experiments are summarized in Fig. 2 and Table 1. Titration of MDCC-N212C clHisRS with histidine produced a 6% fluorescence quench, with a calculated Kd of 88 ± 8.4 μm (Fig. 2A). No fluorescence changes were observed upon titrations with ATP alone. Titration of the histidyl-adenylate analogue HSA into MDCC-HisRS showed that the inhibitor binds much more tightly than histidine, with a Kd of 12.7 nm (Fig. 2B). A stoichiometry of 1.65 ± 0.27 molecules of HSA bound per dimer indicates the apo-enzyme is capable of binding 2 mol of HSA per active site of the dimer, consistent with crystallographic studies in which the electron density for the authentic histidyl-adenylate substrate was found in both active sites (17).

FIGURE 2.

Substrate binding by fluorescently labeled HisRS. A, relative fluorescence change associated with histidine titration into 100 nm MDCC labeled HisRS (monomer). Data are fit to a hyperbolic binding equation (Equation 2, “Experimental Procedures”). B, relative fluorescence change plotted against HSA concentration. Data are fit to a quadratic binding equation (Equation 3, “Experimental Procedures”). C, relative fluorescence changes associated with ATP titration into 100 nm MDCC-N212C clHisRS (monomer) saturated with 2 mm histidinol (○) and 2 mm histidine (●). The fit for the histidinol data is to the hyperbolic binding equation (Equation 3, “Experimental Procedures”).

TABLE 1.

Equilibrium constants determined from steady state fluorescence at 25 °C and pH 7.5

| Substrate | Concentration range | % Fluorescence quench at saturation | Equilibrium dissociation constant |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | % | μm | |

| Histidine | 25–2000 | 6 | 88 ± 8.4 |

| ATP (when titrated into HisRS:HisOH | 1–2000 | 11 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| HSA | 0.01–1.4 | 15 | 0.0127 ± 0.008 |

When ATP was titrated into MDCC-conjugated HisRS saturated with the histidine analog histidinol, an additional 11% quench in fluorescence intensity was observed. An apparent Kd of 2.5 ± 0.1 μm could be calculated for this binding event (Fig. 2C). The absence of a fluorescence signal with ATP alone suggests that either ATP binding alone is either weak or fails to elicit structural changes detectable by fluorescence. When MDCC-N212C clHisRS pre-saturated with the authentic substrate histidine was titrated with ATP, a more complicated set of fluorescence signals was observed. At concentrations of ATP in the range of 1–100 μm, a quench in fluorescence was observed. As ATP was increased above 250 μm, the sign of the fluorescence change reversed, and an enhancement was observed (Fig. 2C). Thus, when HisRS is saturated with histidine or histidinol, ATP binding produces a robust fluorescence change that may be indicative of significant structural changes. In addition, the productive adenylation reaction appears to be characterized by at least one additional fluorescence state.

Asymmetric Conformational Changes Accompany Amino Acid Activation

To obtain rates associated with elementary steps of amino acid activation, stopped-flow experiments that featured rapid mixing of the HisRS·histidine complex with ATP were carried out. However, as seen in steady state, analysis of the results was complicated by multiple fluorescent states along the reaction pathway. At concentrations below 500 μm ATP, a transient fluorescent decay was observed (data not shown). As concentrations of ATP approached 500 μm, the amplitude of the signal steadily decreased until the transient could not be reliably distinguished from the background signal (data not shown). As a consequence of the complex change in fluorescence sign relative to substrate concentration, it was not possible to process the stopped-flow data featuring histidine analytically, and thereby extract elementary rate constants.

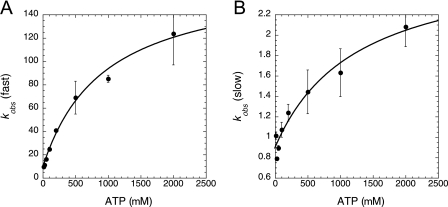

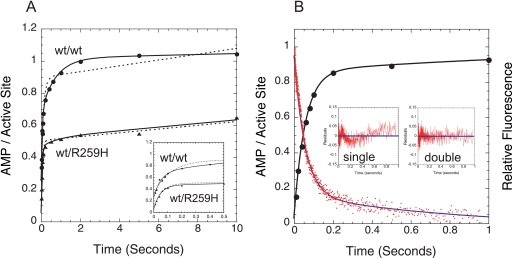

By contrast, the data obtained when the HisRS·histidinol complex was rapidly mixed with Mg-ATP were more straightforward to interpret. When MDCC-N212C clHisRS was rapidly mixed with histidinol or ATP alone, no fluorescence transients were observed (data not shown). However, rapid mixing of MDCC-N212C clHisRS preincubated with 2 mm histidinol with varying (12.5 μm to 2 mm) concentrations of ATP produced progress curves that were most accurately described by double exponentials. Fitting to a double exponential increased R2 and decreased the magnitude of the residuals. Significantly, each of the two rates observed for the biphasic stopped-flow progress curves were hyperbolically dependent on ATP concentration (Fig. 3), suggesting that both transients are likely to be reporting on a two-step process where the binding of ATP is in rapid equilibrium with an enzyme·substrate complex that is undergoing a first order transformation.

FIGURE 3.

Stopped-flow kinetic studies of HisRS·histidinol binding of ATP. Rates of transient fluorescent changes associated with ATP binding to 100 nm MDCC-labeled clN212C HisRS saturated with 2 mm histidinol, as measured by stopped-flow fluorometry. In a typical experiment, one syringe contained 0.5 μm MDCC-labeled HisRS and 2 mm histidinol, whereas the variable syringe contained 0.025 to 10 mm Mg2+-ATP. Reactions were performed at 25° C and pH 7.5. A, plot of kobs(fast) extracted from the biphasic progress curves. B, plot of kobs(slow) extracted from the biphasic progress curves. Error bars represent ± S.E.

The hyperbolic dependence of kobs on substrate allowed k−2, k+2, and a KdATP to be extracted for each (25). When the data were analyzed according to a two-step rapid equilibrium model (Scheme 1), the limiting values for the “fast” exponential were k−2(fast) = 8.4 + 2.9 s−1, k+2(fast) = 164 ± 16 s−1, and KdATP = 0.94 ± 0.23 mm (Fig. 3 and Table 2). For the slow exponential, the respective values were k−2 (slow) = 0.89 ± 0.06 s−1, k+2(slow) = 1.9 ± 0.5 s−1, and Kd′ATP = 1.25 ± 0.7 mm.

TABLE 2.

Rate constants for amino acid activation determined by pre-steady-state kinetics

| Reaction conditions (substrate concentrations) | Method | Rate constant of active site #1 | Rate constant of active site #2 | Kd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | s−1 | mm | ||

| 2 mm Histidine 100 μm ATP | Rapid quench | 18 ± 4.7 | 0.68 ± 0.16 | NDa |

| 2 mm Histidine 200 μm ATP | Rapid quench | 33.8 ± 7.3 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | ND |

| 2 mm Histidinol 100 μm ATP | Stopped flow | 24.7 ± 1.7 | 1.1 ± 0.07 | ND |

| 2 mm Histidinol 200 μm ATP | Stopped flow | 40.8 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.08 | ND |

| 2 mm Histidinol | Stopped flow | (kf): 164 ± 16 | (kf): 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.94 ± 0.2 |

| 0.025–10 mm ATP | (krev): 8.4 ± 3 | (krev): 0.89 ± 0.06 | 1.25 ± 0.7 |

a ND, not determined.

Conformational Changes Are Rate-limiting for Product Formation

Depending on the physical or chemical process that serves to limit the rate of the adenylation reaction, the rates of fluorescence changes associated with substrate binding could be either equal to, or faster than, the rate of adenylation chemistry. To correlate the rate of conformational change observed by stopped-flow fluorescence with the rate of product formation, the production of AMP was measured under pre-steady state conditions by rapid chemical quench flow. MDCC-N212C clHisRS was mixed with a stoichiometric excess of histidine, [α-32P]ATP, and pyrophosphatase, and then quenched by addition of 3 m sodium acetate. The accumulation of AMP was followed by TLC and autoradiography.

In the absence of tRNAHis, the kinetics of histidyl-adenylate formation were biphasic, and the amplitude term of each exponential was equivalent to one active site of the HisRS homodimer (Fig. 4A). At an ATP concentration of 100 μm, fitting of the progress curve of AMP production to a double exponential produced rate constants of kobs1 = 18.1 ± 4.7 s−1 and kobs2 = 0.68 ± 0.16 s−1. These were within a factor of two of the values determined by stopped-flow fluorometry at the equivalent substrate concentrations (Fig. 4B and Table 2). When ATP concentrations were raised to 200 μm, the biphasic rates increased to kobs1 = 33.8 ± 7.3 s−1 and kobs2 = and 2.6 ± 1.3 s−1, respectively, which are also close to the values determined by stopped-flow.

FIGURE 4.

Product formation of AMP by wild-type and heterodimeric HisRS and comparison of formation of AMP by rapid quench with ATP binding by stopped-flow fluorescence. A, rapid quench progress curves for the production of AMP by the wild-type MDCC-N212C clHisRS homodimeric enzyme (●) or wt/R259H heterodimeric HisRS (▴). 10 μm HisRS (dimer) and 2 mm histidine were mixed with 200 μm [α-32P]ATP. Single and double exponential fits (with an additional linear phase, as noted under “Results”) are represented as dotted and solid lines, respectively. B, comparison of the rate of AMP produced per active site (●), as measured by rapid chemical quench, to the rate of stopped-flow fluorescence at equivalent concentrations of ATP (100 μm). The curve for the latter, shown in red, represents the average of five independent injections. Both data sets were fit to the bi-exponential equation (“Experimental Procedures”, Equation 4) by non-linear regression. The residuals for fits to single or double exponential equations are shown below.

The detection limits and sensitivity requirements of monitoring adenylate formation by chemical quench flow using TLC separation of α-32P-labeled nucleotide constrained the concentrations of ATP over which the rate of amino acid activation could be measured. At concentrations >200 μm, the resolution of AMP from total nucleotide becomes increasingly difficult (data not shown). Accordingly, the rapid quench assay could not be employed at concentrations >200 μm in ATP. In all progress curves where AMP production was monitored in the absence of tRNA, the double exponential term was followed by a linear term that is an order of magnitude less than the rate of the slow site. Previously, we have proposed that this rate represents the rate of reiterative adenylate synthesis and destruction in site 2 of the dimer (20).

The observations reported thus far leave open the formal but unlikely possibility that the double exponential observed is characteristic of both active sites in the dimer, rather than a consequence of an asymmetric dimer. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the amino acid activation activity of a heterodimeric HisRS construct in which one active site of the dimer contains a substitution that largely abolishes activation function. Previous experiments have shown that the R259H substitution reduces the rate of amino acid activation by over three orders of magnitude relative to wild type (17). Under enzyme and substrate concentrations that were equivalent to those of parallel experiments performed on the wild-type homodimer, the amplitude of amino acid activation by the wt/R259H heterodimer was one-half that of the wild-type homodimer (Fig. 4A). With respect to the rate of amino acid activation, the progress curve of the wt/R259H heterodimer could be fit either by single or double exponential equations, with the latter providing a slightly (R2 = 0.997 versus 0.996) improved fit. However, the amplitude of the second exponential phase was <10% of the total signal, strongly suggesting that the activity of the heterodimer is more accurately described as mono-exponential. (The second phase could well represent residual activity present in the R259H subunit.) This was in marked contrast to the wild-type homodimer, which was significantly better described by a double exponential (Fig. 4A). Here, the amplitude for the two exponential phases was nearly 1:1, with the observed rate constants clearly separated by over an order of magnitude (Table 2). Critically, the rate constant for the first, faster exponential of the wild-type homodimer (18.1 s−1) was equivalent to the 17.7 s−1 observed for the wt/R259H construct, strongly supporting the assignment of this rate and amplitude to the functional active site of the heterodimer. These and the foregoing experiments support the conclusion that the two exponentials seen in wild-type HisRS represent distinct rates in each of the two active sites, rather than multiple rates in both sites.

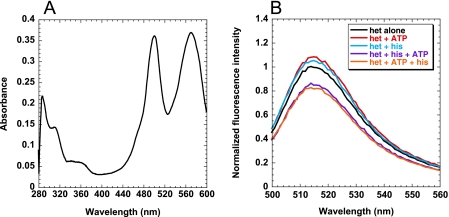

Steady-state RET Experiments

The observation of a fluorescence change per se upon rapid mixing of HisRS·histidinol and ATP is consistent with a potential conformational change but does not define its structural basis. In view of the location of the MDCC probe, one hypothesis is that the fluorescence change is reporting on the movement of the insertion domains, which occurs upon assembly of the histidine binding site (18). To gain addition additional evidence for this proposal, N212C clHisRS heterodimers were engineered with fluorescent donor and acceptor on the respective subunits of the dimer. Separate pools of labeled donor and labeled acceptor molecules were prepared, mixed together, and renatured by following the protocol described under “Experimental Procedures.” The fluorescence probes (AF488 as donor and QSY-7 as a non-fluorescence emitting quencher) were selected on the basis of the 64-Å predicted R0 for this fluorescence resonance energy transfer pair, which is close to the 69-Å Asn-212 to Asn-212′ distance observed in the crystal structure of HisRS from Thermus thermophilus (19). The labeling stoichiometry (donor:acceptor quencher) of the final eluate from nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column isolation was 1:1 (Fig. 5A). Control plateau aminoacylation assays demonstrated that the decreases in aminoacylation activity of the HisRS RET heterodimer relative to wild type were of the same magnitude as MDCC-N212C clHisRS (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

RET by the AF488:QSY-7-labeled clN212C HisRS heterodimer. A, absorbance scan of extrinsically labeled HisRS heterodimer, prepared as described in “Experimental Procedures.” The peaks at 280, 495, and 580 nm correspond to the absorbance of protein tyrosine residues, AF488 donor, and QSY-7 acceptor, respectively. Calculation of molar concentrations using respective extinction coefficients yielded a 1:1:1 ratio. B, steady-state resonance energy transfer of the AF488:QSY-7-labeled N212C clHisRS heterodimer. The wavelength of excitation light was 460 nm, and emission spectra were measured 500–600 nm. Plots shown include AF488:QSY-7 N212C clHisRS heterodimer alone, AF488:QSY-7 N212C clHisRS heterodimer plus 50 μm ATP, AF488:QSY-7 N212C clHisRS heterodimer plus 50 μm histidine, AF488:QSY-7 N212C clHisRS heterodimer plus 50 μm ATP and 50 μm histidine, and AF488:QSY-7 N212C clHisRS heterodimer plus 50 μm histidine followed by 50 μm ATP.

Incubation of 50 nm HisRS heterodimer with 50 μm histidine or 50 μm ATP alone displayed no significant quench of donor fluorescence from that of the heterodimer alone (Fig. 5B). When both histidine and ATP were included, however, transfer efficiencies of 17.6% and 13.9% were observed for the binding of amino acid first or ATP binding first, respectively. Incubation of the AF488-labeled homodimer with both histidine and ATP showed no significant quench, indicating that the signal observed is the result of an authentic RET event (data not shown). Although these efficiencies are too low to permit an accurate measurement of the Asn-212 to Asn-212′ distance, the development of a fluorescence resonance energy transfer signal in response to the binding of productive substrates suggests that the distance between these reporters decreases when a productive reaction occurs. This suggests that the binding of productive substrates is associated with a conformational change that brings the insertion domains of the two subunits closer together.

DISCUSSION

Here, fluorescence and rapid quench experiments were conducted to obtain equilibrium dissociation constants for histidine, ATP and HSA, and to follow the rate of conformational changes associated with assembly of the active site of the adenylation reaction. These studies revealed two important properties of the HisRS-catalyzed adenylation reaction. First, HisRS was found to exhibit asymmetry with respect to the rate of catalysis, catalyzing adenylation in the two active sites at rates differing by at least two orders of magnitude. Second, comparisons of the rates of rapid quench and stopped-flow fluorescence suggest that the rate of chemistry proceeds no faster than the rate of fluorescence change. The differential rates of adenylate synthesis observed in the HisRS dimer may be a consequence of inherent structural features of the enzyme, whereby formation of a single adenylate in site 1 impedes substrate recruitment and/or chemistry in site 2.

A Fluorescence-based ARS Reporter System That Reports on the Adenylation Reaction

The intrinsic tryptophan signal associated with HisRS is weak, motivating the development of a modified version of HisRS that can be readily labeled by extrinsic fluorescence probes. Systems based on extrinsic probes have the advantage that the observed signal reflects changes in the chemical environment of the probe at a specified location in the structure, as opposed to reflecting the summed effects of tryptophan distributed throughout the structure. The absorbance maximum of MDCC is at a longer wavelength than either tryptophan or nucleotides, eliminating potential inner filter effects associated with ATP or tRNA. Steady-state pyrophosphate exchange and aminoacylation assays demonstrated that the multiple substitutions and conjugation with MDCC had minimal effect on the activation reaction, but did confer an ∼12-fold decrease on aminoacylation function. This suggests a potential steric clash between the probe and the tRNA acceptor stem, a possibility that remains to be explored in further work.

By several different criteria, MDCC-N212C clHisRS accurately reports on the activation reaction. In addition to the strong fluorescence signals associated with histidine, ATP, and HSA binding, the equilibrium dissociation constants for histidine and HSA measured here compare favorably with the Kd for histidine measured by equilibrium dialysis for Salmonella typhimurium HisRS (31) and the KI for inhibition of ProRS by its respective prolylsulfamoyl adenylate analog (32). The conclusion that MDCC-labeled HisRS faithfully monitors the binding of small substrates like histidine and ATP is also supported by the agreement of the forward, reverse, and apparent equilibrium constants determined by stopped-flow fluorometry with values determined in other systems. Owing to the complex nature of the signals associated with the authentic adenylation reaction substrates (histidine and ATP), experiments here focused on using histidinol. With this substrate analog, the two forward rates of adenylation measured by stopped-flow experiments (164 and 1.8 s−1, respectively) and apparent Kd for ATP (0.94 and 1.3 mm) bracket corresponding values determined for other ARSs using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. In ThrRS, the forward rate of aminoacylation measured by stopped-flow fluorometry was 29 s−1, and the Kd for ATP from the ThrRS·Thr complex was 450 μm (30). In IleRS, the comparable values are 60 s−1 and 70 μm (33). Notably, the system with the most similar values is LysRS, where use of the chemically blocked substrate l-lysine amide (which, like histidinol, is capable of binding but not adenylate formation) gives rise to a fluorescence change with a forward rate of 221 s−1, and a Kd for ATP of 575 μm (34).

The finding of similar values for these parameters by use of both intrinsic and extrinsic probes argues that, for the adenylation reaction at least, any structural perturbations associated with conjugation by MDCC have limited functional consequences. Further validation of the MDCC-HisRS system is provided by the equivalence (at equal substrate concentrations) between the rates of formation of AMP measured by rapid quench and the rates of conformational change measured by stopped-flow fluorometry (Fig. 4B). To a first approximation, this suggests that the forward rate of adenylation is limited by the rate of conformational change in the active site. In view of the results of the RET experiments, one component of this conformational change is likely to be a rigid body rotation of each insertion domain toward its respective active site, which may serve to sequester the unstable histidyl adenylate away from potentially hydrolytic solvent molecules.

The Rates of Formation of Adenylate in the Two Active Sites of HisRS Are Asymmetric

A striking feature of HisRS-catalyzed amino acid activation is that the progress curves are bi-exponential, whether the reaction is followed by rapid quench or stopped-flow fluorometry. Possible explanations for this behavior include (i) each active site intrinsically possesses two different rates of amino acid activation; (ii) the HisRS preparations are composed of two populations, one of which is more active than the other; or (iii) the dimer is inherently asymmetric, with one active site exhibiting faster kinetics than the other. The model that the HisRS preparation contains two different populations is disfavored, because such a mixed population would show altered steady-state kinetics (i.e. a non-linear Lineweaver-Burk plot), multiple rates for aminoacyl transfer, and perhaps resolve as two distinct species by chromatography. None of these has ever been observed. Alternatively, the two exponentials could represent two discrete events in a single active site, such as ATP binding followed by a first order conformational change. However, kobs1 and kobs2 both vary in a hyperbolic fashion with increasing ATP, suggesting that each fluorescence change is described by a two-step mechanism. In addition, the close correspondence between the rapid quench and stopped-flow data argues that each exponential is associated with the formation of product.

In contrast, several independent lines of evidence argue for the inherent asymmetry of the dimer and a differential rate of adenylate synthesis in the two different subunits. First, the amplitudes of the two exponentials in rapid quench experiment are each equivalent to 1 mol per mol of dimers, and parallel what is observed in an active site titration experiment (data not shown). Second, the HisRS·adenylate complex obtained after spin chromatography of the complete reaction with substrate excess possesses 1 mol of adenylate per mol of dimers, suggesting that the second molecule is not held as tightly as the first (4). Finally, drastically reducing the ability of one of the two subunits in the dimer to catalyze adenylate by mutation eliminates the second, slower exponential while leaving the rate of the first exponential virtually unchanged (Fig. 4A). We also demonstrated previously that tRNAHis and HisRS variants compromised at identity determinants are uniformly reduced in their ability to depress the rate of adenylate formation (20). The burst kinetics of AMP formation and amplitude of 1 mol of AMP per mol of dimers observed in these experiments provide evidence that, in the presence of tRNA, the formation of the second mole of adenylate is delayed until after the first mole of aminoacyl-tRNA has formed. Accordingly, cognate tRNA can be seen to perform two notable functions during aminoacylation. In addition to serving as the substrate to which the cognate amino acid is attached, tRNA also serves to attenuate the rate of adenylate synthesis in the first subunit, and to accelerate the rate of adenylate synthesis in the second subunit. In the context of the complete aminoacylation reaction, where cognate tRNA can exert its effect, adenylate synthesis occurs no faster than the ∼2 s−1 rate that governs overall aminoacylation.

Do All Dimeric ARSs Share Similar Properties for Activation?

Reaction schemes in which the progress in each subunit is dependent on the status of the other subunit have been described as “flip-flop” mechanisms (35). In addition to severe negative cooperativity, these systems exhibit Michaelis-Menten behavior under steady-state conditions, i.e. the asymmetry of the system is occult. ARSs uniformly conform to classic Michaelis-Menten kinetics under steady-state conditions, and positive or negative cooperativity in aminoacylation kinetics is not observed, save for special cases involving mutations in the dimeric interface (36). When asymmetries have been observed, they have been confined to amino acid binding, or differences in the rate of adenylation reaction measured under pre-steady-state conditions. Among the dimeric class I enzymes, Tyr- and TrpRS bind 1 mol of amino acid in the absence of ATP, and two in its presence (9, 37). Similarly, the class II dimeric enzyme PheRS binds only 1 mol of amino acid in the absence of ATP and 2 mol in its presence (38). Both active sites are capable of hydrolyzing ATP during the burst phase of adenylate production; however, affinities between the two sites differ by a factor of 10–15. Similarly, the biphasic progress curve seen in stopped-flow fluorescence of class I MetRS from Bacillus stearothermophilus corresponds to a biphasic rapid chemical quench progress curve observed for adenylate production, with rates that differ by 2.5 orders of magnitude between the two active sites (39). These observations suggest that the asymmetry reported here is not, strictly, a consequence of the class II dimeric structure. Rather, it appears to be a characteristic property of both class I and class II multimeric ARSs.

This study suggests that the asymmetry observed in HisRS and, by extension, other ARSs, may largely be a consequence of the absence of the tRNA in the activation reaction. Each subunit is capable of performing adenylation chemistry, but the absence of the tRNA prevents the coupling between the two subunits that normalizes the rate of amino acid activation to the overall rate of aminoacylation. In the context of the full reaction, tRNA plays a crucial role in coordinating the activities of the two subunits. In vivo, this coupling could serve a biological useful function, preventing the excessive consumption of ATP by reiterative adenylate synthesis and destruction under conditions where no cognate tRNA is available to accept amino acid. In view of the high ATP consumption associated with protein synthesis, such a mechanism provides a connection between protein synthesis and the overall energy charge of the cell (40). The coupling mechanism described here illustrates the critical role of the ARSs in maintaining this regulatory circuit.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 GM54899 (to C. S. F.) and F32 GM19739 (to M. L. B.).

- ARS

- aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

- AF488

- AlexaFluor 488

- HSA

- 5′-O-[N-(l-histidyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine

- HisRS

- histidyl-tRNA synthetase

- MDCC

- 7-diethylamino-3-((((2-maleimidyl)ethyl)amino)carbonyl)coumarin

- RET

- resonance energy transfer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eriani G., Delarue M., Poch O., Gangloff J., Moras D. (1990) Nature 347, 203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibba M., Soll D. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 617–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.First E. A. (2005) in ( Ibba M., Francklyn C., Cusack S. eds) in The Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases, pp. 328–352, Landes Bioscience, Georgetown, TX [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guth E., Connolly S. H., Bovee M., Francklyn C. S. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 3785–3794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minajigi A., Francklyn C. S. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17748–17753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cusack S. (1997) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 881–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedouelle H. (2005) in The Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases ( Ibba M., Francklyn C., Cusack S. ed) pp. 111–124, Landes Biosciences, Georgetown, TX [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter C. W., Jr. (2005) in The Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases ( Ibba M., Francklyn C., Cusack S. ed) pp. 99–110, Landes Bioscience, Georgetown, TX [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakes R., Fersht A. R. (1975) Biochemistry 14, 3344–3350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fersht A. R., Mulvey R. S., Koch G. L. E. (1975) Biochemistry 14, 13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fersht A. R. (1975) Biochemistry 14, 5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaremchuk A., Kriklivyi I., Tukalo M., Cusack S. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 3829–3840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward W. H., Fersht A. R. (1988) Biochemistry 27, 1041–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trézéguet V., Merle M., Gandar J. C., Labouesse B. (1986) Biochemistry 25, 7125–7136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauenstein S. I., Hou Y. M., Perona J. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21997–22006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnez J. G., Harris D. C., Mitschler A., Rees B., Francklyn C. S., Moras D. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 4143–4155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnez J. G., Augustine J. G., Moras D., Francklyn C. S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7144–7149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu X., Janson C. A., Blackburn M. N., Chhohan I. K., Hibbs M., Abdel-Meguid S. S. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 12296–12304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aberg A., Yaremchuk A., Tukalo M., Rasmussen B., Cusack S. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 3084–3094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guth E. C., Francklyn C. S. (2007) Mol. Cell 25, 531–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dibbelt L., Pachmann U., Zachau H. G. (1980) Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 4021–4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dibbelt L., Zachau H. G. (1981) FEBS Lett. 129, 173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman R., Gibson B., Donovan D., Biemann K., Eisenbeis S., Parker J., Schimmel P. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 10063–10068 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan W., Augustine J., Francklyn C. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 6559–6568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francklyn C. S., First E. A., Perona J. J., Hou Y. M. (2008) Methods 44, 100–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francklyn C., Harris D., Moras D. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 241, 275–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward W. H., Fersht A. R. (1988) Biochemistry 27, 5525–5530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakowicz J. R. (1999) Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, pp. 369–370, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fersht A. R., Ashford J. S., Bruton C. J., Jakes R., Koch G. L., Hartley B. S. (1975) Biochemistry 14, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bovee M. L., Pierce M. A., Francklyn C. S. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 15102–15113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Natale P., Schechter A. N., Castronuovo Lepore G., De Lorenzo F. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 62, 293–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heacock D., Forsyth C., Shiba K., Musier-Forsyth K. (1996) Bioorg. Chem. 24, 273–289 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pope A. J., Lapointe J., Mensah L., Benson N., Brown M. J., Moore K. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31680–31690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takita T., Akita E., Inouye K., Tonomura B. (1998) J. Biochem. 124, 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazdunski M., Petitclerc C., Chappelet D., Lazdunski C. (1971) Eur. J. Biochem. 20, 124–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Commans S., Blanquet S., Plateau P. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 8180–8189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazat J. P., Merle M., Graves P. V., Merault G., Gandar J. C., Labouesse B. (1982) Eur. J. Biochem. 128, 389–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fasiolo F., Ebel J. P., Lazdunski M. (1977) Eur. J. Biochem. 73, 7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blanquet S., Fayat G., Waller J. P., Iwatsubo M. (1972) Eur. J. Biochem. 24, 461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atkinson D. E. (1968) Biochemistry 7, 4030–4034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]