Abstract

The INI1/SMARCB1 protein product (INI1), a component of a transcription complex, was recently implicated in the pathogenesis of schwannomas in two members of a single family with familial schwannomatosis. Tumors were found to have both constitutional and somatic mutations of the SMARCB1 gene and showed a mosaic pattern of loss of INI1 expression by immunohistochemistry, suggesting a tumor composition of mixed null and haploinsufficient cells. To determine if this finding could be extended to all tumors arising in familial schwannomatosis, and how it compares with other multiple schwannoma syndromes [sporadic schwannomatosis and neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2)] as well as to sporadic, solitary schwannomas, we performed an immunohistochemistry analysis on 45 schwannomas from patients with multiple schwannoma syndromes and on 38 solitary, sporadic schwannomas from non‐syndromic patients. A mosaic pattern of INI1 expression was seen in 93% of tumors from familial schwannomatosis patients, 55% of tumors from sporadic schwannomatosis, 83% of NF2‐associated tumors and only 5% of solitary, sporadic schwannomas. These results confirm a role for INI1/SMARCB1 in multiple schwannoma syndromes and suggest that a different pathway of tumorigenesis occurs in solitary, sporadic tumors.

Keywords: Schwannoma, NF2, Schwannomatosis, INI1, SMARCB1, expression

The SMARCB1 (also known as INI1, hSNF5 and BAF47) is a tumor suppressor gene that maps to chromosome band 22q11.2. Biallelic inactivation of SMARCB1 is frequent in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) and malignant RT; aggressive malignant tumors of the central nervous system and kidneys in children. Constitutional mutations of SMARCB1 can be seen in rare familial cases of AT/RT (5). The protein encoded by SMARCB1, the INI1 protein, is a subunit of the SWI/SNF ATP‐dependent chromatin‐remodeling complex and is ubiquitously expressed in all cell types examined (8). AT/RTs occurring both sporadically and in the context of a tumor suppressor gene syndrome, show diffuse loss of expression of INI1 by immunohistochemistry, a feature often used in the pathologic diagnosis of these tumors 9, 10.

SMARCB1 lies in the candidate region for familial schwannomatosis, a form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas without vestibular nerve involvement 6, 7. In a recent report (2), constitutional and somatic mutations of the SMARCB1 gene were found in tumors from a single kindred with familial schwannomatosis. The loss of nuclear INI1 protein expression by immunohistochemistry was seen in four separate tumors from two members of this family. However, in contrast to the immunostaining pattern of INI1 in AT/RT, the loss of INI1 expression was seen in only a subset of tumor cells suggesting a mosaic makeup of null and haploinsufficient cells. Furthermore, several previous studies have identified somatically acquired mutations in the neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) gene in familial schwannomatosis tumors 4, 6), but in tumors from this family, no molecular evidence of NF2 involvement was seen, raising the question of how representative this family may be. Here, we report an expansion of these results to other familial schwannomatosis kindreds as well as the analysis of the INI expression pattern in tumors associated with other multiple schwannoma syndromes (sporadic schwannomatosis and NF2) and in solitary, sporadic schwannomas.

We analyzed the INI1 expression in 83 schwannomas representing the four distinct clinical subgroups: familial schwannomatosis (15 tumors from 10 patients in 5 families), sporadic schwannomatosis (18 tumors from 11 patients), NF2‐associated schwannomas (12 tumors from 12 patients) and solitary, sporadic schwannomas (38 tumors from 38 patients). All the schwannomas included in the study were non‐vestibular, in order to eliminate possible site‐related bias. The diagnosis of patients was established by review of the medical record in accordance with published guidelines 1, 7. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB).

Briefly, formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissue sections were immunostained using a commercial INI1 antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) along with appropriate controls: AT/RT as the negative control, and medulloblastoma and normal cortex as the positive controls. Antigen retrieval was achieved by microwaving, steaming in a Borg Decloaker RTU for 48 minutes (primary body antibody concentration 1:50) or by using the Ventana BenchMark XT Autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA), with the Ventana “Ultra View Universal DAB Detection Kit” and heat‐induced epitope retrieval (HIER) (primary antibody concentration of 1:25).

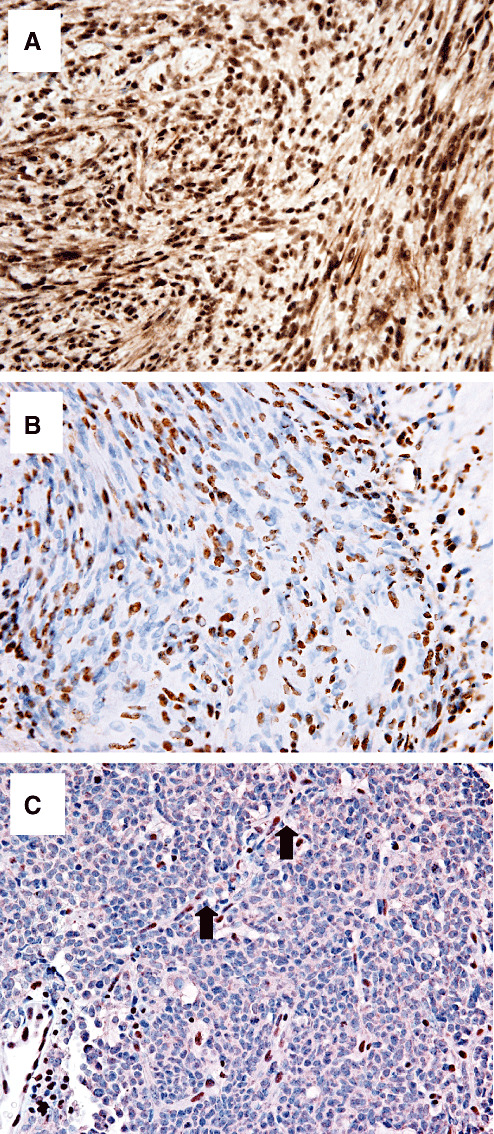

The INI1 immunostaining was interpreted as showing either a diffuse positive nuclear staining consistent with retained expression (Figure 1A) or a mosaic pattern of mixed positive and negative nuclei, consistent with the loss of expression in a subset of tumor cells (Figure 1B). In cases with a mosaic pattern, there was both considerable intertumoral and intratumoral variability, ranging from <10% to >50% immunonegative nuclei. A diffuse immunonegative pattern, as typically observed in AT/RT (Figure 1C) was not seen in any of the schwannoma samples. In most mosaic cases, the negative and positive cells were intimately intermixed.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of INI1 in schwannomas. A. Solitary, sporadic schwannoma showing diffuse immunopositive staining. B. Schwannoma from a familial schwannomatosis patient showing a mosaic pattern with a subset of immunonegative tumor cells intimately intermixed with immunopositive nuclei. C. Negative control, atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor shows diffuse immunonegative tumor; immunopositive capillary endothelial cell nuclei provide an internal positive control (arrows).

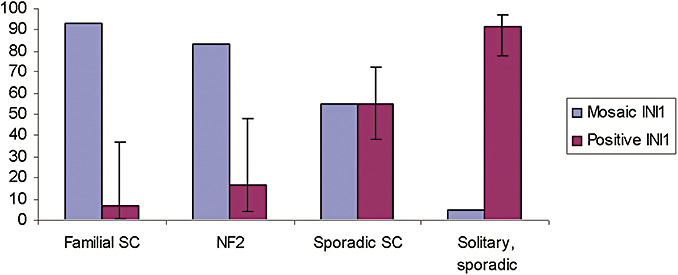

The mosaic pattern was observed in most cases of familial schwannomatosis (14/15; 93%) and NF2‐associated schwannomas (10/12; 83%) and in some cases of sporadic schwannomatosis (10/18; 55%) but was found only in a few of the solitary, sporadic schwannomas (2/38; 5%) (Figure 2). We used generalized estimating equations methodology to calculate standard errors and 95% confidence intervals for the proportions with INI1 positive in each of the groups. The estimates and 95% confidence intervals for positive, diffuse INI1 staining were: 7% for familial schwannomatosis (1%, 37%), 55% for sporadic schwannomatosis (38%, 72%), 17% for NF2 (4%, 48%) and 92% for solitary sporadic schwannomas (78%, 97%). For the mosaic pattern of INI1 staining, the estimates and 95% confidence intervals were 93% for familial schwannomatosis, 45% for sporadic schwannomatosis, 83% for NF2 and 8% for solitary, sporadic schwannomas.

Figure 2.

Distribution of patterns of INI1 expression in schwannomas clinical subtypes. Most of the schwannomas of hereditary type, neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) and familial schwannomatosis (familial SC) have a mosaic pattern of staining, in contrast to the diffuse pattern of solitary, sporadic schwannomas. Sporadic schwannomatosis (sporadic SC) tumors show both patterns of staining; SC = schwannomatosis.

Schwannomatosis is a recently recognized, third form of neurofibromatosis characterized by the presence of multiple non‐vestibular schwannomas, often associated with pain, and typically without vestibular involvement (7). Over two‐thirds of schwannomatosis patients have no family history (sporadic schwannomatosis) (7). Non‐vestibular schwannomas may occur also in the context of NF2 and as sporadic, solitary tumors in the general population. Clinical distinction of schwannomatosis from early forms of NF2 or from sporadic, solitary cases may be challenging. While biallelic inactivation of NF2 occurs in all forms of schwannomas (3), only NF2 patients harbor constitutional NF2 mutations in non‐neoplastic tissues. Our previous work has defined a candidate region for schwannomatosis locus in close proximity to the NF2 gene on chromosome 22q, a region that includes the SMARCB1/INI1 locus.

Our study of the INI1 expression in 83 syndromic and solitary, sporadic schwannomas confirms and expands the findings reported by Hulsebos et al (2). We found a mosaic pattern of the INI1 expression in most familial schwannomatosis schwannomas, confirming its involvement in the pathogenesis of these tumors. The mosaic pattern is suggestive of two populations of cells intermixed within the tumor mass. Surprisingly, this pattern was not limited to schwannomatosis, but was also found in NF2‐associated cases, suggesting that INI1 loss may also play a role in the pathogenesis of NF2‐associated schwannomas. In contrast, solitary sporadic schwannomas retained the INI expression, implicating different pathways of tumorigenesis in hereditary syndromes and in solitary tumors. Sporadic schwannomatosis‐associated tumors appear to be heterogeneous; some show INI1 loss of expression; similar to the familial schwannomatosis tumors, while others retain the INI1 expression; similar to sporadic solitary tumors. Further work is needed to determine if multiple tumors (or multiple samples from the same tumor) in sporadic schwannomatosis have the same INI expression pattern. Molecular analysis of the tumors to elucidate the underlying molecular alterations in all types of schwannomas is warranted and additional efforts are needed to correlate the expression patterns on INI1 protein to underlying SMARCB1/INI1 molecular alterations as well as to analyze possible cointeraction of NF2 and SMARCB1/INI1 that may explain the observed similarity of the INI1 expression pattern in NF2 and familial schwannomatosis tumors.

From a clinical standpoint, the different patterns of INI1 staining may be helpful in distinguishing familial and sporadic schwannomatosis; especially while definitive molecular diagnostics is not yet available. Although the mosaic pattern of INI1 staining is not definitive for a familial form of the disease, a diffuse, positive INI1 staining is suggestive that the patient will not become a founder of the familial form of the disease.

In summary, this is the first study to report the alterations of the INI1 expression in a large series of schwannomatosis and NF2‐associated tumors, and while it elucidates the role of SMARCB1 in various forms of schwannoma, it also raises many additional questions. The underlying molecular mechanism and sequence of events that lead to the formation of tumors with the mixed population of cells also remain unclear. Further studies are necessary to correlate the underlying molecular changes in SMARCB1 to the INI1 expression patterns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Children's Tumor Foundation (ASR) and from the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (MM). The authors thank Drs Michael Lawlor and Pavan Auluck for their help with the graph.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, Korf B, Marks J, Pyeritz RE et al (1997) The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA 278:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hulsebos TJM, Plomp AS, Wolterman RA, Robanus‐Maandag EC, Baas F, Wesseling P (2007) Germline mutation of INI1/SMARCB1 in familial schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet 80:805–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jacoby LB, MacCollin M, Barone R, Ramesh V, Gusella JF (1996) Frequency and distribution of NF2 mutations in schwannomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 17:45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jacoby LB, Jones D, Davis K, Kronn D, Short MP, Gusella J, MacCollin M (1997) Molecular analysis of the NF2 tumor‐suppressor gene in schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet 61:1293–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Janson K, Nedzi LA, David O, Schorin M, Walsh JW, Bhattacharjee M et al (2006) Predisposition to atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor due to an inherited INI1 mutation. Pediatr Blood Cancer 47:279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacCollin M, Willett C, Heinrich B, Jacoby LB, Acierno JS Jr, Perry A et al (2003) Familial schwannomatosis: exclusion of the NF2 locus as the germline event. Neurology 60:1968–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacCollin M, Chiocca EA, Evans DG, Friedman JM, Horvitz R, Jaramillo H et al (2005) Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology 64:1838–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muchardt C, Yaniv M (2001) When the SWI/SNF complex remodels the cell cycle. Oncogene 28:3067–3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perry A, Fuller CE, Judkins AR, Dehner LP, Biegel JA (2005) INI1 expression is retained in composite rhabdoid tumors, including rhabdoid meningiomas. Mod Pathol 18:951–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sigauke E, Rakheja D, Maddox DL, Hladik CL, White CL, Timmons CR, Raisanen J (2006) Absence of expression of SMARCB1/INI1 in malignant rhabdoid tumors of the central nervous system, kidneys and soft tissue: an immunohistochemical study with implications for diagnosis. Mod Pathol 19:717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]