Abstract

Microbial pathogens have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for evasion of host innate and adaptive immunities. PFam54 is the largest paralogous gene family in the genomes of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease bacterium. One member of PFam54, the complement-regulator acquiring surface proteins 1 (BbCRASP-1), is able to abort the alternative pathway of complement activation via binding human complement regulator factor H (FH). The gene coding for BbCRASP-1 exists in a tandem array of PFam54 genes in the B. burgdorferi genome, a result apparently of repeated gene duplications. To help elucidate the functions of the large number of PFam54 genes, we performed phylogenomic and structural analyses of the PFam54 gene array from ten B. burgdorferi genomes. Analyses based on gene tree, genome synteny, and structural models revealed rapid adaptive evolution of this array through gene duplication, gene loss, and functional diversification. Individual PFam54 genes, however, do not show high intra-population sequence polymorphisms as genes providing evasion from adaptive immunity generally do. PFam54 members able to bind human FH are not monophyletic, suggesting that human FH affinity, however strong, is an incidental rather than main function of these PFam54 proteins. The large number of PFam54 genes existing in any single B. burgdorferi genome may target different innate-immunity proteins of a single host species or the same immune protein of a variety of host species. Genetic variability of the PFam54 gene array suggests that universally present PFam54 lineages such as BBA64, BBA65, BBA66, and BBA73 may be better candidates for the development of broad-spectrum vaccines or drugs than strain-restricted lineages such as BbCRASP-1.

Keywords: Borrelia burgdorferi, Complement-Regulator Acquiring Surface Protein-1, Lyme disease, Factor H, immune evasion, cspA

Introduction

A microbial pathogen must overcome innate and adaptive immunity of its vertebrate host to ensure successful infection, reproduction, and transmission (Ewald, 1994; Frank, 2002). The selective pressure for resisting host defence is expected to be especially strong for an obligate parasite. Lyme disease, the most common vector-borne disease in Europe and North America, is caused by spirochetes of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.l.) species group (Piesman and Gern, 2004; CDC, 2007). This bacterial species group consists of more than ten genospecies defined by sequence clusters on gene phylogenies, such as B. burgdorferi sensu stricto found in both Europe and North America, B. afzelii and B. garinii in Eurasia, and B. bissettii in North America (Baranton et al., 1998). B. burgdorferi is an obligate parasite maintained in a transmission cycle consisting of small mammals and birds as reservoirs and Ixodes ticks as vectors (Piesman and Gern, 2004). Adaptation of B. burgdorferi to a life of obligate parasitism is apparently facilitated by a large proportion of surface located lipoprotein genes in its genome, which are required for tissue attachment, invasion, and immune escape (Fraser et al., 1997; Casjens et al., 2000; Brooks et al., 2006).

One mechanism by which B. burgdorferi may evade the host defence is through the production of a variety of complement-regulator acquiring surface proteins (CRASPs) (Kraiczy et al., 2001). The CRASPs were identified and defined by their affinity for factor H and its alternatively spliced variants, which negatively regulate complement activation in humans (Kindt et al., 2007). At least five CRASP genes, which are not obviously homologous to one another, have been identified in B. burgdorferi strain B31, and their products were named as BbCRASP-1 through -5 respectively (Bykowski et al., 2008). These BbCRASPs differ in their expression profiles during the tick-vertebrate transmission cycle of B. burgdorferi; yet the molecular and cellular processes in which most BbCRASP paralogs in B31 function remain unknown (Brissette et al., 2008; Bykowski et al., 2008).

BbCRASP-1, encoded by the bba68 (cspA) gene in the B31 strain, is perhaps the best characterized CRASP. In vitro study using a cspA mutant and human serum showed that BbCRASP-1 is both necessary and sufficient to provide B31 with resistance to host killing by the complement system (Brooks et al., 2005). An in vivo study based on mice and humans, however, showed no detectable transcripts or protein product of cspA during mammalian infection (McDowell et al., 2006). These observations suggest that cspA is expressed only briefly during mammalian infection and is not expressed during long-term infection in either tick or mammals (von Lackum et al., 2005). A high-resolution atomic structure of BbCRASP-1 has been determined, which suggested that it binds factor H (FH) and its alternatively spliced variant factor H-like protein 1 (FHL-1) through a cleft formed between two BbCRASP-1 molecules (Cordes et al., 2005; Cordes et al., 2006). Evolutionarily, BBA68 is a member of the largest paralogous gene families, PFam54, in the B31 genome (Casjens et al., 2000). There are eleven apparently intact genes, located on four linear plasmids, in this family. Six of these PFam54 genes (along with two truncated family members) exist in a tandem gene array on the lp54 plasmid (Casjens et al., 2000). These PFam54 paralogs differ greatly in their FH/FHL-1 affinity, based on the finding that none of the PFam54 proteins in the European B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain ZS7 is able to bind human FH/FHL-1 except for the BBA68 ortholog (Kraiczy et al., 2006). The inability to interact with human FH/FHL-1 has been demonstrated for BBA69, the evolutionarily most closely related paralog of BbCRASP-1 in strain B31 (McDowell et al., 2005). It appears, therefore, that PFam54 paralogs have diverged considerably in their functions. One PFam54 homolog in B. afzelii has been found to bind strongly to human FH, but not FHL-1, while no PFam54 homolog in a B. garinii strain has strong FH affinity (Wallich et al., 2005). PFam54 homologs with strong FH/FHL-1 binding ability have also been identified in B. spielmanii strains (Herzberger et al., 2008). It is not clear whether PFam54 homologs in multiple strains are phylogenetically orthologous to BbCRASP-1. One would expect that if the FH/FHL-1 affinity were essential for Borrelia to survive in its host, various PFam54 homologs with such a function would be maintained as orthologs during B. burgdorferi diversification. In other words, we expect the FH/FHL-1 binding function to be monophyletic on a PFam54 gene tree.

Here we investigate the evolutionary history of the PFam54 homologs from ten B. burgdorferi s.l. strains. Evolutionary computation helps the elucidation of gene functions in at least three ways. First, functional annotation of genes can be more reliably transferred among orthologs, and evolutionary analysis is essential for distinguishing between orthologs and paralogs in multiple genomes (Eisen and Fraser, 2003). Orthologs – gene copies due to the divergence of species or strains – are expected to maintain the same functions in different strains, while paralogs – gene copies due to duplication in a single genome – often diverge in their molecular functions (Fitch, 2000). Second, structure of a novel protein can be modelled based on the structure of its homologs (Zvelebil and Baum, 2008). Furthermore, binding sites of a protein molecule may be identified by analysis of evolutionary conservation of individual residues (Landau et al., 2005; Mihalek et al., 2006). Third, functionally important sites within genes can be revealed by testing the presence of selective constraints and adaptive changes at individual codons and on individual branches of an evolutionary tree (Yang et al., 2000). Using a phylogenomic approach, we are able to clarify the orthologous and paralogous relations among members of the PFam54 gene family in ten B. burgdorferi s. l. genomes. We built three-dimensional models of representative PFam54 paralogs, which suggested structural mechanisms of their FH/FHL-1 affinity. Intriguingly, our comparative analysis of the PFam54 gene array reveals high rates of gene duplication, gene loss, and adaptive sequence evolution. We propose that the large differences in the PFam54 gene array among B. burgdorferi genospecies may be a consequence of the differences in host species composition. Similarly, variability of the PFam54 gene array within a genospecies may reflect host specialization of clonal groups coexisting in the same ecological niche.

Materials and Methods

Genomic sequences and ortholog identification

Sequences of the PFam54 gene array, located near one terminus of the on lp54 plasmids, have been determined in at least ten B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains based on either whole-genome or targeted sequencing. Genome sequences were downloaded from GenBank for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31 (accession AE000783) (Fraser et al., 1997; Casjens et al., 2000), B. afzelii PKo (CP000395), and B. garinii PBi (CP000013) (Glockner et al., 2004; Glockner et al., 2006). We obtained draft genome sequences of four strains: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains N40, JD1, and 297, and B. bissettii strain DN127 (Casjens, 2008). We obtained from GenBank sequences of the CRASP-1 cluster for three additional strains: B. afzelii MMS (AJ78368), B. garinii ZQ1 (AJ786369), and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto ZS7 (AJ784964 & CP001199) (Wallich et al., 2005; Kraiczy et al., 2006). Also included are sequences of five CRASP-1 homologs from five Borrelia spielmanii strains (AM749200-AM749204) (Herzberger et al., 2008).

To identify genome-wide PFam54 homologs, we used the BBA68 protein sequence from strain B31 as a query in a PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) search against a database of all predicted ORFs from the seven published or draft Borrelia genomes with an e-value cutoff of 10−5. BBA68 homologs, including all ORFs of the PFam54 gene arrays from strains MMS, ZQ1, and ZS7, were aligned using ClustalW (Larkin et al., 2007). Protein maximum likelihood tree reconstruction was carried out using the PHYLIP program PROML on 100 bootstrapped alignments, followed by tree summarization using CONSENSE (Felsenstein, 1989). Orthologous genes were identified by first running the program NOTUNG (Chen et al., 2000) to infer events of gene duplication and gene loss based on parsimonious reconciliation of the PFam54 gene tree with the strain tree. The strain tree, shown on the leftmost side of Figure 2, is based on a current understanding of B. burgdorferi genospecies phylogeny (Qiu et al., 2008). Our working definition of a set of orthologs is a clade on the reconciled gene tree – including the lost genes – that closely resembles the strain phylogeny. Visualization of the PFam54 gene array was achieved by using customized PERL scripts written based on the Bio::Graphics modules of the BioPerl (bioperl.org) library. Nucleotide sequences of the PFam54 gene arrays from draft genomes (N40, JD1, 297, and DN127) were deposited in GenBank under accessions XXXXX-XXXXXX (Note to Journal: sequence submission in progress).

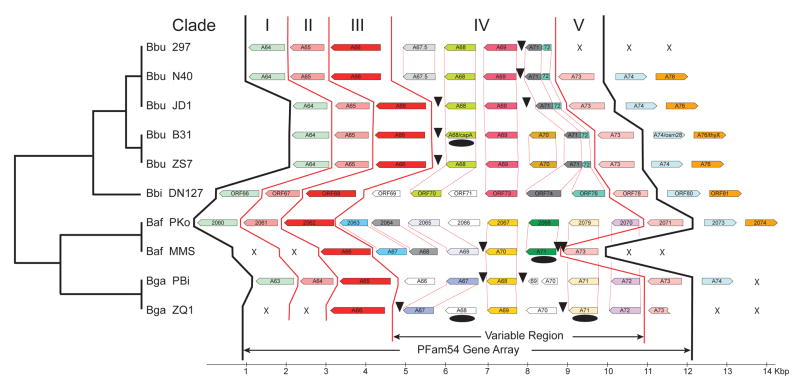

Figure 2. Synteny map of lp54 ends containing the PFam54 gene array.

Genomes are arranged in a phylogenetic order with, from top to bottom, five B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains, one B. bissettii strain, two B. afzelii strains, and two B. garinii strains. One-to-one orthologous ORFs, based on the gene phylogenies (Figure 1), share the same colour and ORFs with no clear orthologs are coloured black. The lp54 plasmid of B. burgdorferi is conserved in gene order except in the region consisting of BbCRASP-1 homologs. An array of close BbCRASP-1 homologs (Figure 1B), a region sandwiched by more distantly related homologs (bba64, bba65, and bba66 on one side, and bba73 on the other side), is the most variable region. The gene content variability of the PFam54 gene array is caused by frequent gene duplication, sequence diversification, and gene loss (indicated by arrows).

PAML tests of positive selection

A phylogenetic tree of the BBA68 ortholog dataset was constructed in MrBayes and rooted using the PBi gene BGA66 sequence as an outgroup. The BBA68 dataset and corresponding gene tree were used for PAML tests of positive natural selection under Branch Site and Site models (Yang, 2007). In the Branch Site model, the foreground branch (hypothesized to be under positive selection) was set as the ancestral branch of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. The Branch Site model was run twice: 1) allowing positive selection on the foreground branch, and 2) fixing the foreground branch at KA/KS = 1, representing neutral evolution. These two fittings were compared in a nested likelihood ratio test at one degree of freedom. Site model involved fitting the M1a (nearly neutral model) and M2a (selection model) models onto the BBA68 ortholog gene tree and performing a likelihood ratio test with two degrees of freedom.

Homology modelling

The BbCRASP-1 from Borrelia burgdorferi (PDB identifier: 1W33) (Cordes et al., 2005) was used as the structural template for modelling representative PFam54 proteins, which were aligned to the template by using the fold recognition program FUGUE (Shi et al., 2001) with highly significant z scores ranging from 14.48 to 35.90 (Supplement Table 1). The modelling was performed using the model building programs, MODELLER (Sali, 1995) and NEST (Petrey et al., 2003). Loop refinement was done with Loopy (Xiang et al., 2002) and the prediction of side-chain conformations with SCWRL3.0 (Canutescu et al., 2003) and SCAP (Xiang et al., 2007). The monomer models of BBA68 paralogs and orthologs were structurally superimposed with the experimentally determined structure of BbCRASP-1 using CE (Shindyalov and Bourne, 1998). Electrostatic profiles were calculated at salt concentration of 0.1 M KCl and contoured at +1 kT/e (blue) and −1 kT/e (red) using the program GRASP (Nicholls et al., 1991).

In this study, we have assumed that functional structures of PFam54 proteins are homodimers according to earlier studies (Cordes et al., 2005; Cordes et al., 2006). The modelled dimers were analyzed for their structural and biophysical properties, including the electrostatics, hydrophobicity, and shape, using the surface property analysis tools in the program GRASP (Nicholls et al., 1991). Analysis of homodimer interface of BbCRASP-1 and its homologs, including the complementarities of molecular surface, electrostatic potential and hydrophobicity, was carried out using the online classPPI server (Tsuchiya et al., 2006). Surface exposed residues, marked as those residues whose solvent accessible area is more than 30% of the maximum solvent accessibility on the surface, were identified with the SPDBViewer (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

Results

Five major lineages of PFam54 proteins

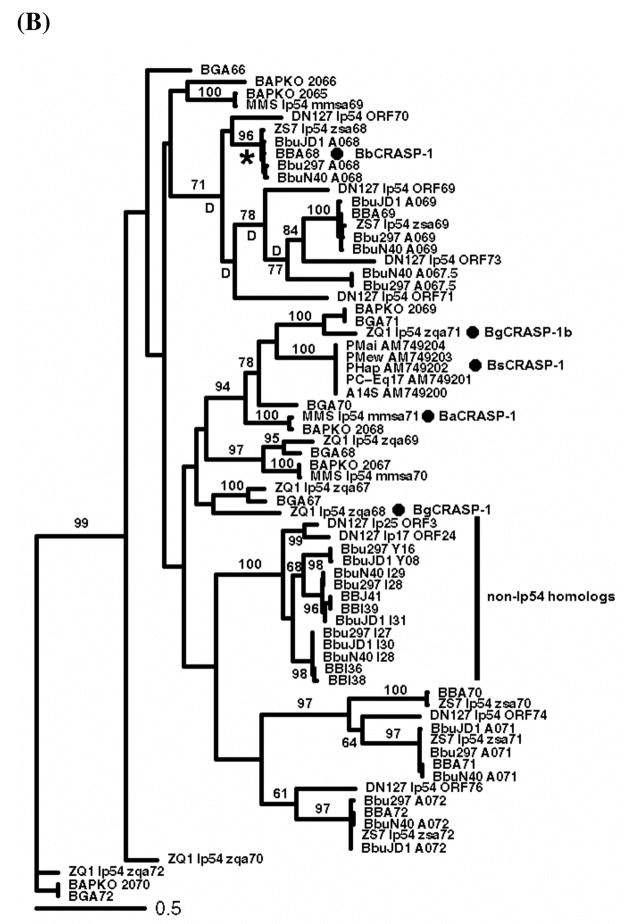

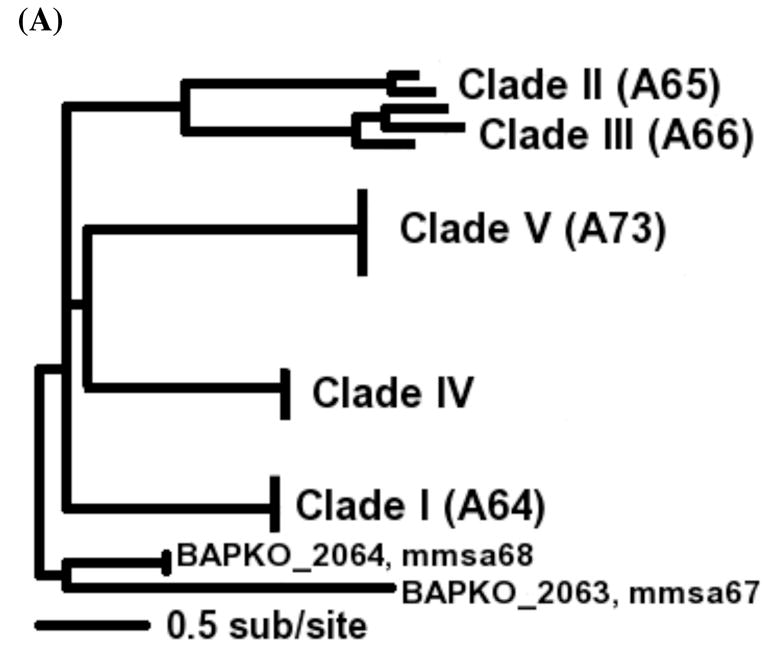

Figure 1 shows two maximum likelihood trees of PFam54 proteins obtained from a PSI-BLAST search of seven Borrelia complete genome sequences and three additional PFam54 gene arrays. These likelihood-based trees are consistent with a PFam54 tree from a previous study based on protein sequence distances (Hughes et al., 2008). The present gene phylogenies show additional phylogenetic information by providing bootstrap support values for the branches and by including PFam54 proteins from DN127, a close outgroup of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. The Figure 1A tree reveals five major clades separated from each other by a genetic distance of at least one amino acid substitution per site. Clades I, II, III, and V consist of genes that are orthologous to stain B31 genes bba64, bba65, bba66, and bba73, respectively. Each of these clades comprises one gene from each genome, forming a strictly 1:1 orthologous group. (Absence of orthologs from some strains in these four clades is because these genes were not within the sequenced genomic regions. For example, orthologs of bb64 and bba65 were not sequenced in strains MMS and ZQ1, and the bba73 ortholog was not in the draft genome assembly of strain 297.)

Figure 1. Protein trees of PFam54 homologs.

(A) A PROML tree of all BbCRASP-1 homologs showing five major clades. The tree is rooted on four B. afzelii sequences based on the assumption that the most recent common ancestor of these ten strains possessed all five clades. (B) A majority-rule consensus tree of Clade IV homologs. Branch support values were obtained by running PROML with 100 bootstrapped alignments. Branches without bootstrap values are not significant (bootstrap values < 60). “*” denotes the ancestral branch of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto BbCRASP-1 orthologs and was fixed as the foreground branch in the PAML test for detection of lineage specific positive selection. “D” labels nodes where gene duplication occurred, as inferred by NOTUNG. The gene tree shows that FH/FHL-1 binding proteins recognized as BaCRASP-1, BgCRASP-1, and BsCRASP-1 (Wallich et al., 2005; Herzberger et al., 2008) are not exclusive orthologs of BbCRASP-1.

Clade IV consists of the closest homologs of BbCRASP-1 (Figure 1B) and has previously been reported as the TIGR new paralogous gene family “fam_b_bugdorferi_b31.pep35” (Hughes et al., 2008). This is a larger clade that has multiple members in each genome, defying simple 1:1 orthology. The Clade IV ORFs are located on lp54 in the PFam54 gene array (see next section), with the exception of a sub-clade consisting of all non-lp54 members of PFam54 (Figure 1B). This sub-clade contains ORFs from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. burgdorferi bissettii but none from B. garinii or B. afzelii. It is not clear if their absence in the two later genomes is factual or due to the incompleteness of these genome sequences. Nonetheless, Clade IV sequences exist in all of the sampled genomes.

Based on the strict 1:1 orthology of bba64, bba65, bba66, and bba73 in all strains and the universal presence of the Clade IV genes, it is reasonable to assume that the most recent common ancestor of all Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. strains contained genes from these five major clades. Therefore, we rooted the entire PFam54 protein tree by using four B. afzelii homologs (BAPKO_2063, BAPKO_2064, mmsa67, and mmsa68) as outgroup sequences. These four sequences are distant homologs of BbCRASP-1 and their orthologs are present only in B. afzelii strains and not universally. It appears that these sequences represent two most basal PFam54 lineages that were lost in all genospecies except in B. afzelii (Figure 1A).

Evolutionary variability of the PFam 54 gene array

Based on the gene phylogeny of PFam54 homologs (Figure 1), we identified orthologous gene sets in the ten genome comparison set. Figure 2 is a display of the synteny of the PFam54 genes on lp54 plasmids and we assigned the same colour to genes sharing 1:1 orthology. It is apparent from the synteny map that bba68 is located in a region consisting of an array of rather closely related paralogous Clade IV genes (Figures 1 and 2). This region is flanked by more distant Clade I, II, III, and V homologs that are highly conserved in gene order: orthologs to B31 genes bba64-bba65-bba66 on one side and bba73 on the other side. In fact, the overall synteny of lp54 plasmids is highly conserved among all known Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. strains outside of this variable region. All the genes in this cluster share the same coding strand, and it is possible that these genes form a polycistronic operon; however, it is not known whether they are in fact co-transcribed. For ease of discussion, we call the region from bba64 to bba73 (inclusive) the “PFam54 gene array” and the central region consisting of variable numbers of Clade IV paralogs (including bba68) the “PFam54 variable region” (Figure 2).

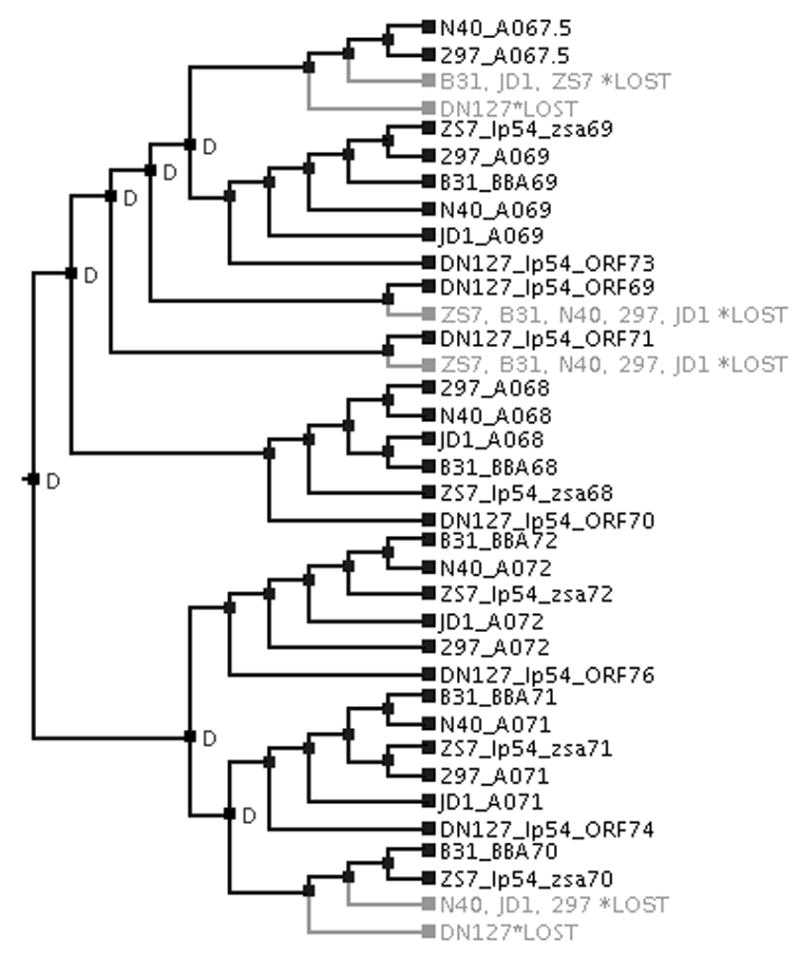

Genes within the PFam54 variable region lack clear synteny among genospecies and even within the same genospecies. For example, among the five B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains, N40 and 297 share a syntenic PFam54 gene array, B31 and ZS7 share a different array, and JD1 has a unique array. B. bissettii DN127 is a close outgroup of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, and it has a six-gene PFam54 variable region. The gene phylogeny suggests that among these DN127 ORFs, ORF70 is orthologous to strain B31 bba68 (coding for BbCRASP-1), ORF73 orthologous to bba69, ORF74 orthologous to bba71, and ORF76 orthologous to bba72. The B31 genes bba71 and bba72 appear to be truncated versions of ORF74 and ORF76, respectively. DN127 ORF69 and ORF71 have no orthologs in B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Parsimonious reconciliation of gene and strain trees suggests seven gene duplication events and six gene loss events in the PFam54 variable region during the evolution of the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. bissettii lineage (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gene tree reconciled with strain phylogeny.

The Clade IV gene tree (excluding non-lp54 homologs as well as homologs from B. garinii, B. afzelii, and B. spielmanii; see Figure 1B) was reconciled with a strain tree (shown in Figure 2) using the program NOTUNG (Chen et al., 2000). “D” indicates where ancestral gene duplication has occurred. Gene lineages that were subsequently lost were colored grey. In total, seven gene-duplication and six gene-loss events have occurred during the evolution of BbCRASP-1 close homologs.

Surprisingly, we found no 1:1 orthology of any genes in the PFam54 variable region between the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto–B. bissettii lineage and the B. garinii–B. afzelii lineage (Figure 2). Similar to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, the gene order of the PFam54 gene array varies among strains of the same B. garinii or B. afzelii genospecies. Synteny variability in these strains may be explained by six gene losses (two in afzelii and four in B. garinii) (Figure 2). Among the large number of PFam54 paralogs in B. garinii and B. afzelii, only bga68, bga71, and bga72 are present in both genospecies. To summarize, we conclude that the PFam54 gene array, especially its central region, has evolved rapidly during B. burgdorferi s.l. evolution through frequent gene duplications, sequence diversifications, and gene losses. Variability of the PFam54 gene array is associated with genospecies divergence as well as genetic differentiation among clonal groups within the same genospecies.

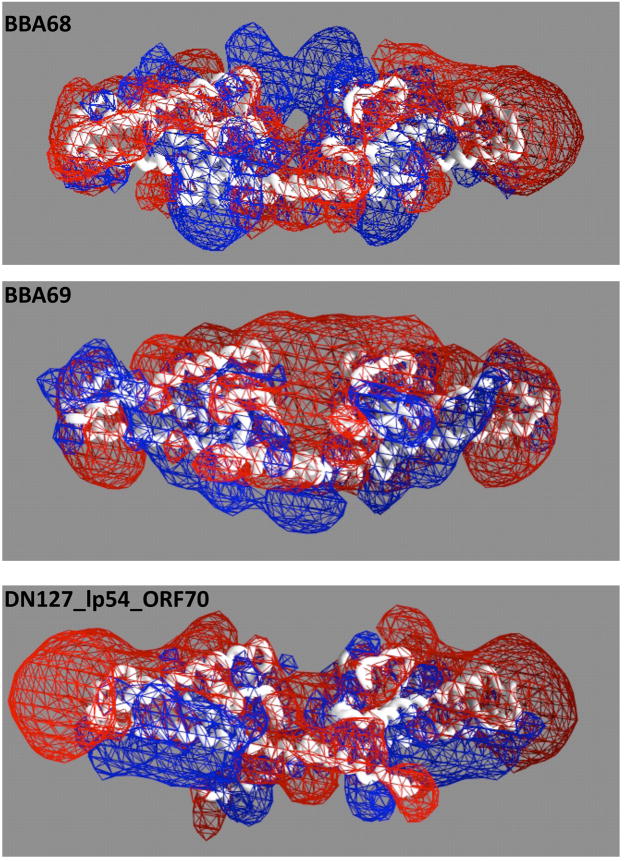

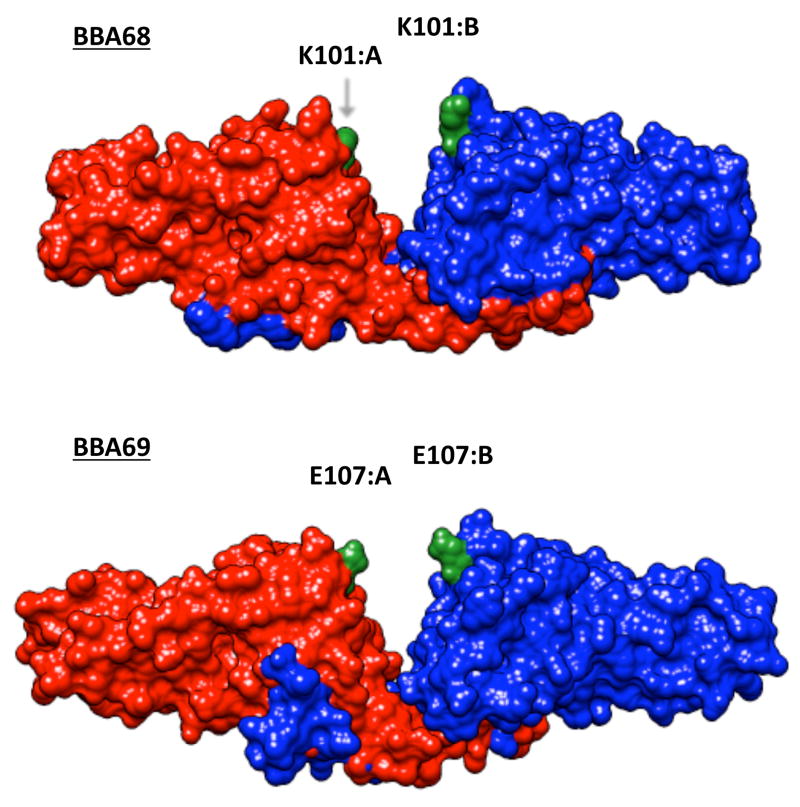

Unique positive charges in the FH/FHL-1 binding cleft

It was proposed that the FH/FHL-1 binding site is a homodimer cleft (Cordes et al., 2006). We therefore focused on the putative binding cleft and its surface exposed residues, defined as residues whose solvent accessible area is more than 30% of the maximum solvent accessibility on the surface. There are eight surface exposed residues within the suggested FH/FHL-1 binding cleft of BbCRASP-1, including Lysine 96, Lysine 99, Lysine 101, Threonine 107, Proline 112, Lysine 136, Glutamic acid 137 and Lysine 151. These eight surface exposed residues are located in two discontinuous regions and are well conserved among BbCRASP-1 orthologs (Figure 4). We have built homology models for over thirty PFam54 proteins. Model quality scores, including the FUGU alignment score, the Prosa score of sequence-template compatibility, the structural similarity score measured by root mean square deviation (RMSD), and the sequence identity and similarity scores, were provided in Supplement Table 1. Homology models of PFam54 proteins in a homodimer configuration suggest a strong positive potential at the binding cleft of BbCRASP-1 that is largely unique to the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto orthologs and absent even in its closest paralog (BBA69) or its closest non-B. burgdorferi sensu stricto ortholog (DN127_lp54_ORF70) (Figure 5A). The lack of positive electrostatic potential in the putative FH binding cleft of BBA69 may explain its demonstrated lack of FH affinity (McDowell et al., 2005). Furthermore, the entrance to the BBA69 cleft is made smaller by a protruding Glutamic acid 32 as shown by a surface structure display (Figure 5B). The monomer models of BBA69 and DN127_lp54_ORF70 are among the most reliable PFam54 models in the present study because of their relatively high sequence identities (49.2% and 69.9%, respectively) to the template. Such sequence identities are near or above the accepted 50% threshold of obtaining accurate Cα positions using comparative modelling (Bordoli et al., 2009).

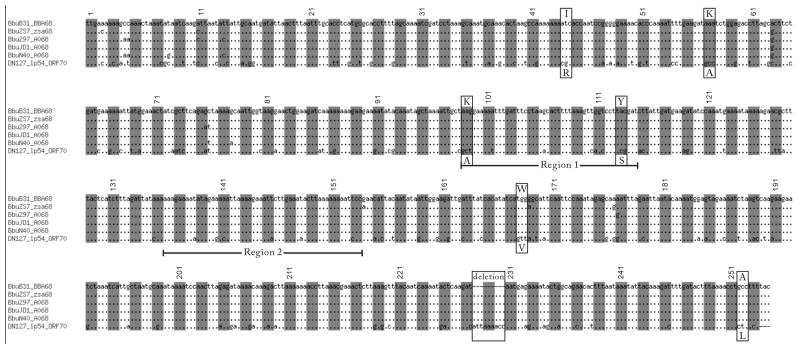

Figure 4. BbCRASP-1 ortholog alignment.

Codon triplets were delineated by shades and numbered. Two underlined regions denote putative FH binding sites extracted from the BbCRASP-1 structure (Cordes et al., 2005). Six codon sites (boxed) were identified in the PAML Branch Site test to be influenced by positive natural selection during the divergence between B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. bissettii. These positive selected sites invariably show base transversion at two or three codon sites between these two genospecies – a highly unlikely event under neutral expectations. A three-codon deletion (not an insertion as determined by using an PBi outgroup sequence) is also boxed.

Figure 5. Surface structures of BbCRASP-1 and its homologs.

Molecular surfaces of BBA68 (PDB accession 1W33) (Cordes et al., 2005) and its paralogs in B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31. The dimmer structures of BBA68 paralogs were derived from homology models of each sequence. (A) Electrostatic potentials at the putative binding cleft, showing that BBA68 is unique in having a binding cleft that is positively charged. All structures are represented as Cα backbone traces and oriented with the binding cleft directed upwards. Electrostatic potentials were calculated and visualized in GRASP (Petrey et al., 2003) at physiological salt concentration. The equipotential contours are fixed at −1 kT/e (red) and +1 kT/e (blue). (B) Molecular surfaces of the BBA68 and BBA69 dimers, showing additional structural variations at the putative binding cleft that may explain their differential FH/FHL affinity.

Positive selection in BbCRASP-1 orthologs

The unique positive charge localized around the putative binding cleft of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto BbCRASP-1 orthologs is not seen in the B. bissettii ortholog or other PFam54 family members. We therefore hypothesize that this charge state may be the result of adaptation, so we examined the nucleotide sequences of BBA68 orthologs for evidence of lineage-specific positive selection. The positive selection test was applied to the ancestral branch of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (marked by an asterisk in Figure 1). The improvement in the log likelihood score is significant (P=0.025) in the PAML Branch Site Model, supporting the presence of lineage-specific positive selection. The improvement in the Site Model is also significant (P=0.018), lending support to site-specific positive selection. We have mapped the amino acid sites identified as under positive selection onto the BbCRSP-1 structure (PDB identifier: 1W33) (Cordes et al., 2005). Figure 4 shows the sequence location of the putative binding cleft regions and six positively selected residues identified in the Branch Site and Site models using the Bayes Empirical Bayes method (Yang et al., 2005). Examination of the nucleotide alignment (Figure 4) revealed that these PAML tests have effectively identified all codon changes that involved double or triple nucleotide transversions between the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains and B. bissettii DN127, which are highly improbably evolutionary events under neutral expectations. Two positively selected sites, Lysine 99 and Tyrosine 113, are located within the putative binding cleft (Figure 4). Both models reported positive selection on Lysine 99. The amino acid change at this site represents a change from a non-charged Valine to a positively charged state and involved substitution of three nucleotides (from GCT to AAG, one transition and two transversions), strongly suggesting adaptive evolution. Positive selection was also found in the dimerization region (Alanine 257 at the C-terminus), yet this substitution does not significantly alter the electrostatic properties. Four positively selected residues, Isoleucine 44, Alanine 73, Tryptophan 168, and Threonine 229, were found outside the putative cleft region of the BbCRASP-1 molecule. Lastly, we note that the three-codon (coding for Ile-Lys-Thr) deletion (determined by using PBi BGA66 as an outgroup sequence) at alignment positions 228–230 represents the largest sequence difference between B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and its outgroup sequences and may cause functional differences.

Discussion

BbCRASP-1 is one of at least five classes of surface proteins of the Lyme disease pathogen B. burgdorferi that play a role in escaping the host complement defence system (Kraiczy et al., 2004; Bykowski et al., 2008). To assist the functional characterization of BbCRASP-1 and its paralogs, we performed a phylogenomic study of the BbCRASP-1 gene-containing PFam54 gene array in ten B. burgdorferi genomes. Our main findings are that PFam54 paralogs have diverged greatly in their sequences, structural characteristics, and functions, and that individual B. bugdorferi strains vary substantially in their PFam54 gene content.

A gene phylogeny of PFam54 proteins from nine of the ten genomes used in the present study has been reported earlier (Hughes et al., 2008). While it has been argued in that study that the genes in the PFam54 variable region comprise a paralogous gene family (“b31_pep_35” according to a TIGR reclassification) distinct from and nonparalogous to other PFam54 genes, it is necessary to note that classification of genes and bacterial strains is hierarchical in nature and depends often on arbitrary cutoff values of sequence divergence based on a gene tree. A statistically more robust criterion of determining sequence homology is based on BLAST e-values, which are a measure of chance sequence similarity. All sequences included in the current study showed BLASTp e-values of 10−5 or lower with BbCRASP-1 and were therefore considered homologs within the former TIGR paralogous gene family PFam54. We improved upon an earlier phylogenetic analysis of PFam54 proteins of (Hughes et al., 2008) by (i) providing bootstrap support values for the branches, (ii) including a B. bissetti strain DN127, a close outgroup of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, (iii) identifying orthology among PFam54 genes through the inference of gene duplication and loss events, (iv) comparing the gene order among genomes, and (v) mapping the FH/FHL-1 binding ability of PFam54 homologs onto the PFam54 gene tree. In the following, we discuss the hypothesis that PFam54 genes may be associated with host specificity of B. burgdorferi clonal groups, and implications of the variability of the PFam54 gene array to its potential as vaccine and drug target.

The polyphyletic and incidental nature of human FH/FHL-1 affinity of PFam54 proteins

Molecular and cellular functions of BbCRASP-1, including the significance of their FH/FHL-1 affinity, are still in debate (Bykowski et al., 2008). BbCRASP-1 was shown to be the only family member in B. burgdorferi sensu stricto able to bind human factor H, and even BBA69, its most closely related homolog, has no factor H affinity (McDowell et al., 2005; Kraiczy et al., 2006). Strong human factor H binding activity has been demonstrated for PFam54 homologs in B. afzelii and B. spielmanii, but not in B. garinii (Wallich et al., 2005; Herzberger et al., 2008). These authors suggested orthology between the FH/FHL-1 binding PFam54 homologs and BbCRASP-1, and named them accordingly as BaCRASP-1 and BsCRASP-1. Gene phylogeny shows, however, that the PFam54 homologs able to bind human FH/FHL-1 are not phylogenetically monophyletic and there is no strictly 1:1 orthology between BaCRASP-1, BsCRASP-1, and BbCRASP-1 (Figures 1 and 2). In fact, since the bba67.5-bba68-bba69 lineage emerged after the split of the B. bissettii-B. burgdorferi sensu stricto lineage from the B. afzelii-B. spielmanii-B. garinii lineage, PFam54 homologs between these two lineages show many-to-many orthology relationships to each other. In other words, except for the BGA72/BAPKO_2070/zqa72 lineage, all Clade IV homologs in B. afzelii and B. garinii are all phylogenetically orthologous to BbCRASP-1 (Figure 1B). Because Clade IV homologs duplicated and diversified independently in the B. bissettii-B. burgdorferi sensu stricto lineage and the B. afzelii-B. spielmanii-B. garinii lineage, it is likely that homologs between these two lineages have evolved substantially different molecular functions.

It is possible that the FH/FHL-1 affinity evolved independently in multiple gene lineages. Equally likely, the polyphyletic nature of human FH/FHL-1 affinity suggests that such a molecular function is an incidental rather than the main function of some PFam54 proteins. Humans are end targets and not reservoir hosts of B. burgdorferi. It is hard to imagine that the strong affinity of some PFam54 proteins to human FH/FHL-1 is a function evolved specifically as an adaptation to human infection. This evolutionary reasoning does not preclude the possibility that PFam54 proteins function as FH binding proteins in B. burgdorferi reservoir hosts, such as the white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) in northeast U.S. It will be interesting to test this hypothesis by combined computational and experimental approaches on the binding specificities of individual PFam54 proteins to FH sequences of natural reservoir species of B. burgdorferi. For example, a model of FH/FHL-1 binding by BbCRASP-1 has been proposed based on structural computation (Cordes et al., 2006). Since a large number of FH sequences from non-human species are now available from genome sequencing projects, it is conceivable that sequence variation of both FH and BbCRASP-1 can be mapped on such a binding model.

Structural variation at putative FH/FHL-1 binding cleft

In addition to the phylogenetic evidence, variation in the binding specificity of BbCRASP-1 paralogs is supported by studies of molecular structures. The binding site on BbCRASP-1 for FH/FHL-1 was first localized at three discontinuous regions consisting of residues 73–101, 132–159, and 197–224 (McDowell et al., 2005). Later, a study mapping the amino acid variability among CRASP-1 paralogs on the BbCRASP-1 structure suggested that a homodimer cleft was the most likely FH/FHL-1 binding location, based on a sequence variation within the cleft associated with FH/FHL-1 binding ability (Cordes et al., 2006). Most recently, a site-mutagenesis study supported the importance of residues 132–159 in FH/FHL-1 binding (Kraiczy et al., 2009). Our evolutionary tests revealed seven sites influenced by positive natural selection during genospecies divergence (Figure 4). Five of these positively selected sites were not located within regions considered important for FH/FHL-1 binding.

Our structural models of BbCRASP-1 paralogs support their hypothesis by showing structural variations, especially the charge state variation, within the putative binding cleft. For example, we hypothesize that the observed lack of binding between BBA69 and FH could be due to the presence of the Glutamic acid 31 residue at the entrance to the binding cleft (Figure 5B). This substitution may change BBA69 to a non-FH/FHL-1 binder for two reasons: Glutamic acid 31 is bulky and blocks the entrance to the binding cleft and it carries a negative charge, which changes the electrostatic profile of the binding cleft making it more negative (Figure 5A). This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the interaction of FH with some FH binding proteins is known, in part, to be a charge mediated interaction, since it can be inhibited by heparin (Kraiczy et al., 2003; Alitalo et al., 2004).

Contrasting patterns of adaptive evolution: innate vs. adaptive response genes

Functional divergence among PFam54 paralogs is also supported by tests of positive natural selection based on rates of nucleotide substitutions. This is based on the expectation that nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions are fixed at a higher rate than synonymous substitutions at codon sites that contribute to species adaptation (Hurst, 2002). Previously, the presence of positive selection was detected among the divergence of BbCRASP-1 paralogs, supporting their adaptive function differentiation (Cordes et al., 2006). Here, we show additional evidence of positive selection during the evolution of BbCRASP-1 orthologs that is associated with the divergence of B. burgdorferi s.l. genospecies. In particular, we present evidence of lineage specific positive selection at the surface exposed Lysine 99 shared by all B. burgdorferi sensu stricto BbCRASP-1 orthologs (Figure 4). Lysine 99 might be a key determinant of FH/FHL-1 binding because it sits at the entrance of the putative binding cleft where it contributes to the positive potential created by it and four other lysine residues, Lysine 96, Lysine 101, Lysine 136, and Lysine 151.

Further evidence for adaptive evolution of the PFam54 genes includes the high variability of the PFam54 variable region within a single B. burgdorferi genospecies. For instance, the PFam54 gene array varies in its paralog content within two strains of B. garinii, two strains of B. afzelii, and five stains of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (Figure 2). Strains 297, N40, JD1, B31, and ZS7 belong respectively to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto ospC clonal groups K, E, C, A, and B2, respectively, and their multilocus phylogeny has been resolved (Margos et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2008). The PFam54 gene array type of four strains (B31, ZS7, N40, and 297) is phylogenetically consistent, with B31 and ZS7 sharing one type and 297 and N40 sharing another type. According to the parsimonious reconciliation of gene and strain trees, the unique JD1 array type is due to the loss of both bba67.5 and bba70 (Figure 3). The ZS7 clonal group (ospC-B2) is a Europe-specific lineage and the B31 clonal group is found in both Europe and North America (Qiu et al., 2008). Yet these two isolates have not diverged in their PFam54 gene array. As more B. burgdorferi genomes become available, evolution history of the PFam54 gene array will be better resolved.

In sum, the genetic variability of the PFam54 genes appears to be driven by three mechanisms of adaptive evolution, including structural and functional diversification among paralogs following gene duplication, maintenance of strain-specific PFam54 gene arrays, and adaptive sequence divergence between orthologs. There is, however, no evidence for balancing selection maintaining a large number of alleles at individual PFam54 loci. There are no excessive amino acid polymorphisms at the bba68 locus among five B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains (Figure 4). Host genes involved in innate defence mechanisms (e.g., FH genes) are more conserved than genes used for adaptive immunity. This is presumably because molecular targets of host innate responses are generic, rather than specific, molecular characteristics of microbial pathogens. For example, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) activate inflammatory responses upon binding molecules common to many pathogen species such as bacterial lipopolysacchrides. Most TLR-related genes are indeed under purifying rather than positive natural selection during primate evolution (Nakajima et al., 2008). Outer surface protein loci, such as ospC and vlsE in B. burgdorferi, which contribute to the escape from host adaptive immunity, in contrast, show strong balancing selection within local pathogen populations (Zhang et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1999).

We conclude that patterns of adaptive evolution of pathogen immune-response genes are indicative of their molecular functions. Genes providing escape from host innate responses, such as PFam54 genes, evolve under purifying selection within populations but vary adaptively with host species differences. In contrast, genes providing escape from host adaptive immunity, such as ospC, maintain high intra-population allelic diversity but perhaps do not contribute to host specificity as suspected (Brisson and Dykhuizen, 2004; Hanincova et al., 2006).

Concluding remarks

We started expecting that PFam54 gene encoding key complement resistance would be maintained as orthologs in all B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. We ended by concluding the high genetic variability and non-orthologous relationships of FH/FHL-1 binding genes in the PFam54 gene array on lp54, a plasmid that otherwise has highly conserved gene synteny. Genetic diversity of the PFam54 gene array is contributed by a large number of apparently functionally distinct paralogs and strain-specific paralog contents. Gene phylogeny shows no exclusive orthology between BbCRASP-1, BaCRASP-1, and BsCRASP-1 proteins, suggesting that their affinity to human FH/FHL-1 proteins may be an incidental rather than the main function of these molecules. Humans are accidental, non-reservoir host of B. burgdorferi. It is more likely that the adaptive diversification of BbCRASP-1 paralogs and strain-specific PFam54 gene arrays are maintained by molecular variation of the complement-resistance mechanisms in natural reservoir species of B. burgdorferi. It has been proposed that the large number of FH binding proteins in the B. burgdorferi genome may be responsible for its ability to infect a wide range of vertebrate host species in the wild (Stevenson et al., 2002). Indeed, it has been demonstrated that B. burgdorferi genospecies prefer different host species and reactivity to the host complement killing was associated with such host specificity (Kurtenbach et al., 2002). The PFam54 gene array variability revealed in the present study thus suggests the intriguing possibility that different BbCRASP-1 paralogs may target the same component of the complement system in various host species and some fortuitously also have this function in humans. For the development of broad-spectrum vaccines and drugs based on PFam54 genes, our results suggest that the universally present PFam54 gene lineages such as bba64, bba65, bba66, and bba73 are perhaps better candidates than csp-1/bba68 (encoding BbCRASP-1). This is because besides these four genes, other BbCRASP-1 paralogs have limited phylogenetic distributions and are often present in a strain- or genospecies-specific manner. Gene products of bba65, bba66, and bba73 were shown to be surface localized (Hughes et al., 2008). All these four conserved genes are up-regulated in infected mouse tissues, suggesting their important roles in establishing infection in mammals including human (Gilmore et al., 2008).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Levy Vargas for informatics support and Dr Lia Di for assisting graphic illustrations. We thank three anonymous reviewers for providing highly constructive comments and suggestions for the original draft. JH is supported by the MBRS-RISE program at Hunter College funded by grant GM60665 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Other supports from this work include a grant from the Lyme Disease Association, Inc. (to SES, CMFL, and BJL) and NIH grants including GM083722 (to WQ), AI056480 (to BJL), AI49003 (to SRC), AI47553 (to SES), and RR03037 (to Hunter College).

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

EW carried out the homology modelling and drafted the manuscript. JH carried out the genome PSI-BLAST search, produced sequence alignments, and performed PAML analyses. YAH carried out gene tree-strain tree reconciliation using Notung. SS and SRC participated in the coordination of the study, conceptual discussion and development of the manuscript. SRC, CMF, BJL, and SES conceived the idea to sequence the genomes of N40, JD1, 297, and DN127, raised the necessary funds, and assembled a Borrelia genome sequencing and analysis team. EFM participated in the sequencing and performed the gene functional annotation of the N40, 297 and DN127 genomes. WQ conceived of this study, participated in its design and coordination, and co-drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alitalo A, Meri T, Chen T, Lankinen H, Cheng ZZ, Jokiranta TS, Seppala IJ, Lahdenne P, Hefty PS, Akins DR, Meri S. Lysine-dependent multipoint binding of the Borrelia burgdorferi virulence factor outer surface protein E to the C terminus of factor H. J Immunol. 2004;172:6195–201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranton G, Marti Ras N, Postic D. Molecular epidemiology of the aetiological agents of Lyme borreliosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:850–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordoli L, Kiefer F, Arnold K, Benkert P, Battey J, Schwede T. Protein structure homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL workspace. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1–13. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette CA, Cooley AE, Burns LH, Riley SP, Verma A, Woodman ME, Bykowski T, Stevenson B. Lyme borreliosis spirochete Erp proteins, their known host ligands, and potential roles in mammalian infection. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008;298(Suppl 1):257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson D, Dykhuizen DE. ospC diversity in Borrelia burgdorferi: different hosts are different niches. Genetics. 2004;168:713–22. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CS, Vuppala SR, Jett AM, Akins DR. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins. Infect Immun. 2006;74:296–304. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.296-304.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CS, Vuppala SR, Jett AM, Alitalo A, Meri S, Akins DR. Complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 imparts resistance to human serum in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 2005;175:3299–308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykowski T, Woodman ME, Cooley AE, Brissette CA, Wallich R, Brade V, Kraiczy P, Stevenson B. Borrelia burgdorferi complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins (BbCRASPs): Expression patterns during the mammal-tick infection cycle. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008;298(Suppl 1):249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canutescu AA, Shelenkov AA, Dunbrack RL., Jr A graph-theory algorithm for rapid protein side-chain prediction. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2001–14. doi: 10.1110/ps.03154503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S. Four ss genomes. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S, Palmer N, van Vugt R, Huang WM, Stevenson B, Rosa P, Lathigra R, Sutton G, Peterson J, Dodson RJ, Haft D, Hickey E, Gwinn M, White O, Fraser CM. A bacterial genome in flux the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:490–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Lyme disease--United States, 2003–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Durand D, Farach-Colton M. NOTUNG: a program for dating gene duplications and optimizing gene family trees. J Comput Biol. 2000;7:429–47. doi: 10.1089/106652700750050871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes FS, Kraiczy P, Roversi P, Simon MM, Brade V, Jahraus O, Wallis R, Goodstadt L, Ponting CP, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Wallich R, Lea SM. Structure-function mapping of BbCRASP-1, the key complement factor H and FHL-1 binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296(Suppl 40):177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes FS, Roversi P, Kraiczy P, Simon MM, Brade V, Jahraus O, Wallis R, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Wallich R, Lea SM. A novel fold for the factor H-binding protein BbCRASP-1 of Borrelia burgdorferi. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:276–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JA, Fraser CM. Phylogenomics: intersection of evolution and genomics. Science. 2003;300:1706–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1086292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald PW. Evolution of Infectious Disease. Oxford University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP-Phylogeny Inference Package. Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch WM. Homology a personal view on some of the problems. Trends Genet. 2000;16:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SA. Immunology and Evolution of Infectious Disease. Princeton University Press; Princeton and Oxford: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum KA, Dodson R, Hickey EK, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb JF, Fleischmann RD, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage AR, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams MD, Gocayne J, Venter JC, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–6. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore RD, Jr, Howison RR, Schmit VL, Carroll JA. Borrelia burgdorferi expression of the bba64, bba65, bba66, and bba73 genes in tissues during persistent infection in mice. Microb Pathog. 2008;45:355–60. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glockner G, Lehmann R, Romualdi A, Pradella S, Schulte-Spechtel U, Schilhabel M, Wilske B, Suhnel J, Platzer M. Comparative analysis of the Borrelia garinii genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6038–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glockner G, Schulte-Spechtel U, Schilhabel M, Felder M, Suhnel J, Wilske B, Platzer M. omparative genome analysis: selection pressure on the Borrelia vls cassettes is essential for infectivity. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–23. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanincova K, Kurtenbach K, Diuk-Wasser M, Brei B, Fish D. Epidemic spread of Lyme borreliosis, northeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:604–11. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.051016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberger P, Siegel C, Skerka C, Fingerle V, Schulte-Spechtel U, Wilske B, Brade V, Zipfel PF, Wallich R, Kraiczy P. Identification and characterization of the factor H and FHL-1 binding complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia spielmanii sp. ov. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JL, Nolder CL, Nowalk AJ, Clifton DR, Howison RR, Schmit VL, Gilmore RD, Jr, Carroll JA. Borrelia burgdorferi surface-localized proteins expressed during persistent murine infection are conserved among diverse Borrelia spp. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2498–511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01583-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst LD. The Ka/Ks ratio: diagnosing the form of sequence evolution. Trends Genet. 2002;18:486–487. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02722-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindt TJ, Goldsby RA, Osborne BA. Immunology. 6. W. H. Freeman and Company; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hanssen-Hubner C, Kitiratschky V, Brenner C, Besier S, Brade V, Simon MM, Skerka C, Roversi P, Lea SM, Stevenson B, Wallich R, Zipfel PF. Mutational analyses of the BbCRASP-1 protein of Borrelia burgdorferi identify residues relevant for the architecture and binding of host complement regulators FHL-1 and factor H. Int J Med Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hellwage J, Skerka C, Becker H, Kirschfink M, Simon MM, Brade V, Zipfel PF, Wallich R. Complement resistance of Borrelia burgdorferi correlates with the expression of BbCRASP-1, a novel linear plasmid-encoded surface protein that interacts with human factor H and FHL-1 and is unrelated to Erp proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2421–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hellwage J, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Brade V, Zipfel PF, Wallich R. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi: mapping of a complement-inhibitor factor H-binding site of BbCRASP-3, a novel member of the Erp protein family. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:697–707. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Rossmann E, Brade V, Simon MM, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Wallich R. Binding of human complement regulators FHL-1 and factor H to CRASP-1 orthologs of Borrelia burgdorferi. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118:669–76. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Brade V, Zipfel PF. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi by acquisition of human complement regulators FHL-1/reconectin and Factor H. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1674–84. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1674::aid-immu1674>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtenbach K, De Michelis S, Etti S, Schafer SM, Sewell HS, Brade V, Kraiczy P. Host association of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato--the key role of host complement. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:74–9. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau M, Mayrose I, Rosenberg Y, Glaser F, Martz E, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margos G, Gatewood AG, Aanensen DM, Hanincova K, Terekhova D, Vollmer SA, Cornet M, Piesman J, Donaghy M, Bormane A, Hurn MA, Feil EJ, Fish D, Casjens S, Wormser GP, Schwartz I, Kurtenbach K. MLST of housekeeping genes captures geographic population structure and suggests a European origin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8730–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800323105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Harlin ME, Rogers EA, Marconi RT. Putative coiled-coil structural elements of the BBA68 protein of Lyme disease spirochetes are required for formation of its factor H binding site. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1317–23. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1317-1323.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Hovis KM, Zhang H, Tran E, Lankford J, Marconi RT. Evidence that the BBA68 protein (BbCRASP-1) of the Lyme disease spirochetes does not contribute to factor H-mediated immune evasion in humans and other animals. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3030–4. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.3030-3034.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalek I, Res I, Lichtarge O. Evolutionary trace report_maker: a new type of service for comparative analysis of proteins. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1656–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Ohtani H, Satta Y, Uno Y, Akari H, Ishida T, Kimura A. Natural selection in the TLR-related genes in the course of primate evolution. Immunogenetics. 2008;60:727–35. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls A, Sharp KA, Honig B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins. 1991;11:281–96. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrey D, Xiang Z, Tang CL, Xie L, Gimpelev M, Mitros T, Soto CS, Goldsmith-Fischman S, Kernytsky A, Schlessinger A, Koh IY, Alexov E, Honig B. Using multiple structure alignments, fast model building, and energetic analysis in fold recognition and homology modeling. Proteins. 2003;53(Suppl 6):430–5. doi: 10.1002/prot.10550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piesman J, Gern L. Lyme borreliosis in Europe and North America. Parasitology. 2004;129(Suppl):S191–220. doi: 10.1017/s0031182003004694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WG, Bruno JF, McCaig WD, Xu Y, Livey I, Schriefer ME, Luft BJ. Wide Distribution of a High-Virulence Borrelia burgdorferi Clone in Europe and North America. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1097–104. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.070880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. Mol Med Today. 1995;1:270–7. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(95)91170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Blundell TL, Mizuguchi K. FUGUE: sequence-structure homology recognition using environment-specific substitution tables and structure-dependent gap penalties. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:243–57. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension (CE) of the optimal path. Protein Eng. 1998;11:739–47. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, El-Hage N, Hines MA, Miller JC, Babb K. Differential binding of host complement inhibitor factor H by Borrelia burgdorferi Erp surface proteins: a possible mechanism underlying the expansive host range of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 2002;70:491–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.491-497.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya Y, Kinoshita K, Nakamura H. Analyses of homo-oligomer interfaces of proteins from the complementarity of molecular surface, electrostatic potential and hydrophobicity. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2006;19:421–9. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lackum K, Miller JC, Bykowski T, Riley SP, Woodman ME, Brade V, Kraiczy P, Stevenson B, Wallich R. Borrelia burgdorferi regulates expression of complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 during the mammal-tick infection cycle. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7398–405. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7398-7405.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallich R, Pattathu J, Kitiratschky V, Brenner C, Zipfel PF, Brade V, Simon MM, Kraiczy P. Identification and functional characterization of complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 of the Lyme disease spirochetes Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2351–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2351-2359.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang IN, Dykhuizen DE, Qiu W, Dunn JJ, Bosler EM, Luft BJ. Genetic diversity of ospC in a local population of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Genetics. 1999;151:15–30. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Soto CS, Honig B. Evaluating conformational free energies: the colony energy and its application to the problem of loop prediction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7432–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102179699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Steinbach PJ, Jacobson MP, Friesner RA, Honig B. Prediction of side-chain conformations on protein surfaces. Proteins. 2007;66:814–23. doi: 10.1002/prot.21099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–91. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen AM. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–49. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wong WS, Nielsen R. Bayes empirical bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1107–18. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JR, Hardham JM, Barbour AG, Norris SJ. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvelebil M, Baum JO. Understanding Bioinformatics. Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.