Abstract

When we are anesthetized, we expect consciousness to vanish. But does it always? Although anesthesia undoubtedly induces unresponsiveness and amnesia, the extent to which it causes unconsciousness is harder to establish. For instance, certain anesthetics act on areas of the brain’s cortex near the midline and abolish behavioral responsiveness, but not necessarily consciousness. Unconsciousness is likely to ensue when a complex of brain regions in the posterior parietal area is inactivated. Consciousness vanishes when anesthetics produce functional disconnection in this posterior complex, interrupting cortical communication and causing a loss of integration; or when they lead to bistable, stereotypic responses, causing a loss of information capacity. Thus, anesthetics seem to cause unconsciousness when they block the brain’s ability to integrate information.

How consciousness arises in the brain remains unknown. Yet, for nearly two centuries our ignorance has not hampered the use of general anesthesia for routinely extinguishing consciousness during surgery. Unfortunately, once in every 1000–2000 operations a patient may temporarily regain consciousness or even remain conscious during surgery (1). Such intraoperative awareness arises in part because our ability to evaluate levels of consciousness remains limited. Nevertheless, progress is being made in identifying general principles that underlie how anesthetics bring about unconsciousness (2–6) and how, occasionally, they may fail to do so.

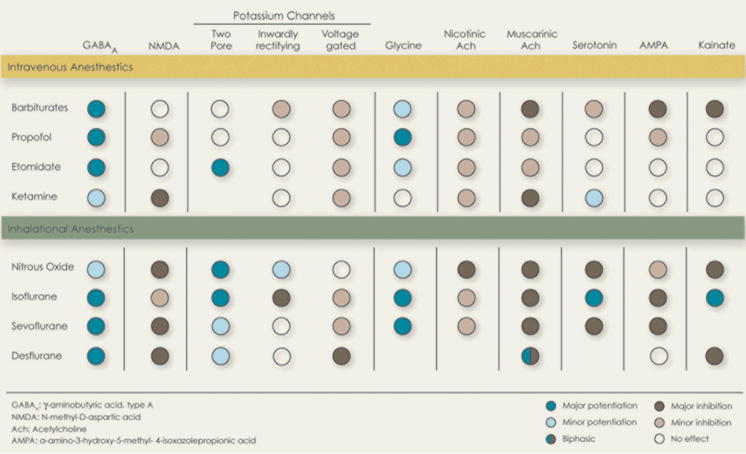

Cellular actions of anesthetics

The cellular and molecular pharmacology of anesthetics has been reviewed extensively (6–8). General anesthetics fall into two main classes: intravenous agents used to induce anesthesia, generally administered together with sedatives or narcotics; and volatile agents, generally used for anesthesia maintenance (Table 1). Anesthetics are thought to work by interacting with ion channels that regulate synaptic transmission and membrane potentials in key regions of the brain and spinal cord. These ion channel targets are differentially sensitive to various anesthetic agents (Table 1).

Table 1.

|

Anesthetics hyperpolarize neurons by increasing inhibition or decreasing excitation (9) and alter neuronal activity: The sustained firing typical of the aroused brain changes to a bistable burst-pause pattern (10) that is also observed in non-rapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep. At intermediate anesthetic concentrations, neurons begin oscillating, roughly once a second, between a depolarized up-state and a hyperpolarized down-state (11). The up-state is similar to the sustained depolarization of wakefulness. The down-state shows complete cessation of synaptic activity for a tenth of a second or more, after which neurons revert to another up-state. As anesthetic doses increase, the up-state turns to a short burst and the down-state becomes progressively longer. These changes in neuronal firing patterns are reflected in the electroencephalogram (EEG) (electrical recording from the scalp) as a transition from the low-voltage, high frequency pattern of wakefulness (known as activated EEG), to the slow wave EEG of deep NREM sleep, and finally to an EEG burst-suppression pattern (12).

The anesthetized patient: Unconscious or unresponsive?

Clinically, at low-sedative doses anesthetics cause a state similar to drunkenness, with analgesia, amnesia, distorted time perception, depersonalization, and increased sleepiness. At slightly higher doses, a patient fails to move in response to a command and is considered unconscious. This behavioral definition of unconsciousness, which was introduced with anesthesia over 160 years ago, while convenient, has drawbacks. For instance, unresponsiveness can occur without unconsciousness. When we dream, we have vivid conscious experiences, but are unresponsive because inhibition by the brainstem induces muscle paralysis (13). Similarly, paralyzing agents used to prevent unwanted movements during anesthesia do not remove consciousness (14).

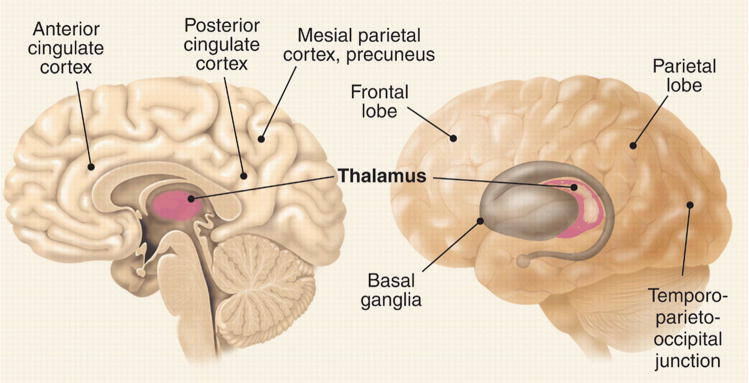

Certain anesthetics may impair a person’s willfulness to respond by affecting brain regions where executive decisions are made. This is not an issue for anesthetics that globally deactivate the brain, but it may be problematic for dissociative anesthetics like ketamine. Low doses of ketamine cause depersonalization, out of body experiences, forgetfulness, and loss of motivation to follow commands (15). At higher doses, it causes a characteristic state in which the eyes are open and the face takes on a disconnected blank stare. Neuroimaging data show a complex pattern of regional metabolic changes (16), including a deactivation of executive circuits in anterior cingulate cortex and basal ganglia (Fig. 1) (17). A similar open-eyed unresponsiveness is seen in akinetic mutism after bilateral lesions around the anterior cingulate cortex (18). In at least some of these cases, patients understand questions, but may fail to respond. Indeed, a woman with large frontal lesions who was clinically unresponsive was asked to imagine playing tennis or to navigate her room and she showed cortical activation patterns indistinguishable from those of healthy subjects (19). Thus, clinical unresponsiveness is not necessarily synonymous with unconsciousness.

Fig. 1.

Brain areas associated with anesthetic effects (references in the textand 2).

At doses near the unconsciousness threshold, some anesthetics block working memory (20). Thus, patients may fail to respond because they immediately forget what to do. At much lower doses, anesthetics cause profound amnesia. Studies with the isolated forearm technique, in which a tourniquet is applied to the arm before paralysis is induced (to allow the hand to move while the rest of the body is paralyzed), show that patients under general anesthesia can sometimes carry on a conversation using hand signals, but post-operatively deny ever being awake (21). Thus, retrospective oblivion is no proof of unconsciousness.

Nevertheless, at some level of anesthesia between behavioral unresponsiveness and the induction of a flat EEG [indicating the cessation of the brain’s electrical activity, one of the criteria for brain death (22)], consciousness must vanish. Therefore, the use of brain function monitors could improve consciousness assessment during anesthesia (23). For instance, bispectral index monitors record the EEG signal over the forehead and reduce the complex signal into a single number that tracks a patient’s depth of anesthesia over time (12). Such devices help guide anesthetic delivery and may reduce cases of intraoperative awareness (24), but they remain limited at directly indicating the presence or absence of consciousness, especially around the transition point. The isolated forearm technique has shown that individual patients can be aware and responsive during surgery even though their bispectral index value suggests they are not (25). Either the EEG is not sensitive enough to the neural processes underlying consciousness, or we still do not yet fully understand what to look for.

The thalamus - switch or readout?

The most consistent regional effect produced by anesthetics at (or near) loss of consciousness is a reduction of thalamic metabolism and blood flow (Fig. 1), suggesting that the thalamus may serve as a consciousness switch (2). Indeed, switch-like effects have been found with a number of thalamic manipulations. For example, GABA agonists (mimicking anesthetic action) injected into the intralaminar nuclei cause rats to rapidly fall asleep, with a corresponding slowing of the EEG (26). Conversely, rats under anesthetic concentrations of sevoflurane can be awakened by a minute injection of nicotine into the intralaminar thalamus (27). In humans, midline thalamic damage can result in a vegetative state (18). Conversely, recovery from the vegetative state is heralded by the restoration of functional connectivity between thalamus and cingulate cortex (28). Also, deep brain electrical stimulation of the central thalamus improved behavioral responsiveness in a patient who was minimally conscious (29).

Nevertheless, thalamic activity does not decrease with all anesthetics. Ketamine increases global metabolism, especially in the thalamus (16). Other anesthetics can significantly reduce thalamic activity at doses that cause sedation, not unconsciousness. For instance, sevoflurane sedation causes a 23% reduction of relative thalamic metabolism when subjects are still awake and responsive (30). Indeed, anesthetic effects on the thalamus may be largely indirect (6, 31, 32). Spontaneous thalamic firing during anesthesia is largely driven by feedback from cortical neurons (33), especially anesthetic-sensitive layer V cells (34). Many of these cells also project onto brainstem arousal centers, so cortical deactivation can reduce both thalamic activity and arousal (35). Also, the metabolic and electrophysiological effects of anesthetics on the thalamus in animals are abolished by removal of the cortex (33, 34, 36). By contrast, after thalamic ablation, the cortex still produces an activated EEG (37), suggesting that the thalamus is not the sole mediator of cortical arousal, nor perhaps is it the most direct one. In patients with implanted brain electrodes undergoing a second surgery to place a deep brain stimulator, the cortical EEG changed dramatically the instant the patients lost consciousness (38). However, there was little change in thalamic EEG activity until 10 minutes later. Conversely, in epileptic patients, during REM sleep (usually associated with dreaming) the cortical EEG was activated as if awake, but the thalamic EEG showed slow wave activity as if asleep (39). Thus, the effects of anesthetics on the thalamus effect may represent a readout of global cortical activity rather than a consciousness switch, and thalamic activity may not be a sufficient basis for consciousness.

Nonetheless, it is premature to write off the thalamus altogether. Perhaps efficient communication among cortical areas requires a thalamic relay (40), in which case thalamic lesions would lead to a functional disconnection despite an activated cortex. A functional thalamic disconnection during anesthesia has been found with neuroimaging (41). Subthreshold depolarization to many cortical areas may be provided by calbindin-positive matrix cells, which are especially concentrated within some intralaminar thalamic nuclei and project diffusely to superficial layers of cortex (42). Cells in intralaminar nuclei can fire at high frequencies, thus providing a coherent oscillatory bias that may facilitate long range cortico-cortical interactions. Therefore, while cortical arousal may occur without the thalamus, consciousness may not.

Cortical effects of anesthetics

Are some cortical areas more important than others for the induction of unconsciousness by anesthetics? Evoked responses in primary sensory cortices - the first relay for incoming stimuli - are often unchanged during anesthesia, deep sleep and in vegetative patients. Also, activity in primary sensory areas often does not correlate with perceptual experience (43). Frontal cortex too may not be essential for anesthetic unconsciousness, as different anesthetics have variable effects on this area. For instance, at equivalent hypnotic doses, both propofol and thiopental deactivate posterior brain areas, but only propofol deactivates frontal cortex (44). Furthermore, large lesions of the frontal cortex do not by themselves produce unconsciousness (45).

Anesthetic-induced unconsciousness is usually associated with deactivation of mesial parietal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus (Fig. 1) (46). These same areas are deactivated in vegetative patients but are the first to reactivate in those who recover (28). Moreover, neural activity in these areas is altered during seizures associated with an impairment of consciousness (47) and in sleep (48). These mesial cortical areas are strategically located at the main hub of the brain’s connectional core (49). They are also part of a default network that is especially active at rest and may be involved in global monitoring of the internal environment and several functions related to the self (50). Nevertheless, mesial cortical areas are deactivated in REM sleep (48), when subjects experience vivid dreams. It is intriguing that at intermediate doses, certain anesthetics, such as nitrous oxide, produce a fairly selective deactivation of posterior mesial cortex (51), yet when these areas start to turn off, subjects report dreamlike feelings with depersonalization and out of body experiences, rather than unconsciousness.

In addition to the core mesial cortical areas, many anesthetics also deactivate or disconnect a lateral temporo-parieto-occipital complex of multimodal associative areas centered on the inferior parietal cortex (Fig. 1). In this case, lesion and anesthesia data are mutually supportive: patients with bilateral lesions at the temporo-parieto-occipital junction show no sign of perceptual experience, despite a flurry of undirected motor activity, a condition called hyperkinetic mutism (18). Thus, a complex of posterior brain areas comprising the lateral temporo-parieto-occipital junction and perhaps a mesial cortical core are the most likely the final common target for anesthetic-induced unconsciousness.

Disruption of cortical integration

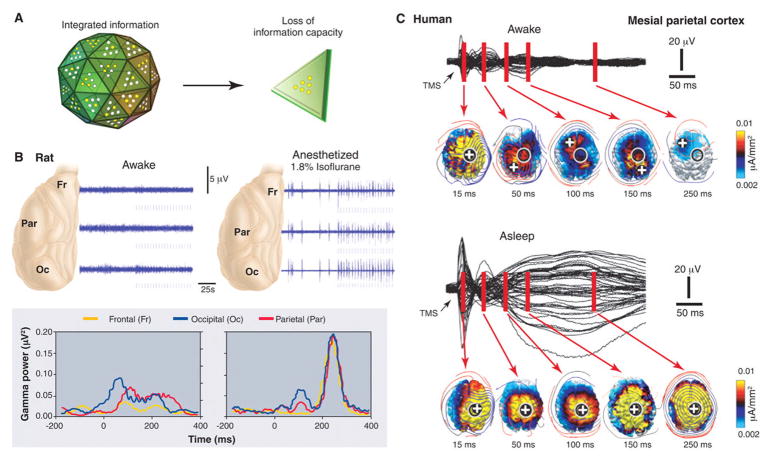

Loss of consciousness may not necessarily require that neurons in these posterior brain areas be inactivated. Instead, it may be sufficient that dynamic aspects of neural activity change, especially if these affect the brain’s ability to integrate information (Fig. 2, 3, 5).

Fig. 2.

Unconsciousness is associated with a loss of cortical integration. (A) The corticothalamic system is represented metaphorically as a large die having many faces, each corresponding to a different brain firing pattern. During conscious waking, the die rolls on a particular face, ruling out all the others and thus generating integrated information. If integration is lost (as in anesthesia or sleep), the die disintegrates into many two-faced dice, each generating 1 bit of information. (B) Anesthesia reduces cortical integration in the rat. (Top) During waking, transfer entropy, a measure of directional interactions among brain areas, is balanced in the feedforward (green) and feedback (red) directions. During anesthesia, feedback transfer entropy (red) is reduced, implying a decrease in front-toback interactions. (Bottom) Responses to a flashing light delivered at 0.2 Hz (arrow) from a representative rat when awake and under 1.1% isoflurane anesthesia (56). When the rat is awake, each flash evokes a sustained gamma frequency (20 to 60 Hz) response in visual occipital cortex (blue) and a later response in parietal association cortex (red). During anesthesia, the occipital response is preserved, although it is shorter (blue), and the parietal response is attenuated, indicating that anesthesia reduces cortical interactions and thus reduces integration. (C) Sleeping reduces cortical integration in humans. EEG voltages and current densities are shown from a representative subject in which the premotor cortex was stimulated with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (black arrow). During waking (top), stimulation evokes EEG responses first near the stimulation site (black circle; the white cross is the site of maximum evoked current) and then in sequence at other cortical locations. During deep sleep (bottom), the stimulus-evoked response remains local, indicating a loss of cortical integration.

Consider first large-scale integration, loosely defined as the ability of different cortical regions to interact effectively (52). When consciousness fades during anesthesia there is a drop in EEG coherence in the γ frequency range (20 to 80 Hz) between right and left frontal cortices and between frontal and occipital regions (4). Anesthetics also suppress fronto-occipital γ coherence in animals, both under visual stimulation and at rest (53). The effect is gradual and much stronger for long-range than for local coherence (53). Anesthetics may disrupt cortical integration (5) by acting on structures that facilitate long-range cortico-cortical interactions, such as the posterior cortical connectional hub (49), certain thalamic nuclei (42), or possibly the claustrum (54). Anesthetics may also disrupt synchronization among distant areas by slowing neural responses (55).

The loss of feedback interactions in the cortex may be especially critical. When rats become unresponsive under anesthesia, information transfer first decreases in the feedback direction (Fig. 3) (56). Also, anesthesia suppresses the late component (>100 ms) of visual responses, possibly by inhibiting feedback connections (57), but not the early feedforward components. Moreover, anesthesia abolishes contextual and attentional modulation of firing, presumably mediated by feedback connections (58). The corticothalamic system may be especially vulnerable to anesthetics due to its small-world organization. Small-world networks have mostly local connectivity with comparatively few long-range connections. Augmented with hubs, such networks maximize interactions while minimizing wiring. By the same token, anesthetics need only disrupt a few long-range connections to produce a set of disconnected components. Indeed, computer simulations demonstrate a rapid state transition at a critical anesthetic dose (59), consistent with a breakdown in network integration.

Fig. 3.

Unconsciousness is associated with a loss of information capacity. (A) As in Fig 2, the corticothalamic system is represented metaphorically as a large die having many faces, each corresponding to a different brain firing pattern. During conscious waking, the die rolls on a particular face, ruling out all the others and thus generating integrated information. If information is lost (as in anesthesia or sleeping), the die is flattened so that it has only two faces (firing patterns). Due to the loss of repertoire, it generates only 1 bit of information. (B) Anesthesia reduces information capacity in rat cortex. (Top) Field potentials recorded before and during light flashes (marks below each trace). During waking (left), flash-evoked field potentials (blue) (light flashes indicated by marks below each trace) are small and variable, being masked by spontaneous neuronal activity. During deep anesthesia (right), bursts of activity occur spontaneously and after each light flash. (Bottom) During anesthesia, the g-burst response is uniform across all three brain regions. Thus, responses are stereotypic and lack regional specificity, indicating a loss of information capacity. (C) Sleeping reduces cortical information carrying capacity in humans. (Top) During waking, stimulation over the mesial parietal cortex produces a specific, sequential pattern of activation. (Bottom) During sleep, stimulation produces a global, stereotypic response that spreads from the stimulation site to most of the cortex, indicating a loss of information capacity. Black traces represent averaged voltage potentials recorded at all electrodes and superimposed, while estimated current density is displayed in absolute scale (63, 64).

Disruption of cortical information capacity

Consider now how anesthetics affect information, defined loosely as the number of discriminable activity patterns. When the repertoire of discriminable firing patterns available to the corticothalamic system shrinks, neural activity becomes less informative, even though it may be globally integrated (52). As described above, at high enough doses several anesthetics produce a burst-suppression pattern in which a near-flat EEG is interrupted every few seconds by brief, quasi-periodic bursts of global activation - a stereotypic, global on-off pattern. Such stereotypic burst-suppression can also be elicited by visual, auditory, and mechanical stimuli (Fig. 4) (60, 61). Thus, during deep anesthetic unconsciousness the corticothalamic system can still be active in fact hyperexcitable and can produce global, integrated responses. However, the repertoire of responses has shrunk to a stereotypic burst-suppression pattern, with a corresponding loss of information, essentially creating a system having only two possible states (on or off). Generalized convulsive seizures provide another example in which consciousness can be lost even though neural activity remains high and highly synchronized: a large portion of the corticothalamic complex is engaged in strong, hypersynchronous activity, but this activity is stereotypic (60, 61).

A bit like sleep

Sleep is the only time when healthy humans regularly lose consciousness. Subjects awakened during slow wave sleep early in the night may report short, thought-like fragments of experience or often, nothing at all (13). Although anesthesia is not the same as natural sleep, brain arousal systems are similarly deactivated (6, 62). Also, as under anesthesia, during slow wave sleep cortical and thalamic neurons become bistable and undergo slow oscillations (1 Hz or less) between up- and down-states. Like animal studies during anesthesia (Fig 3), human studies during slow wave sleep suggest that the bistability of cortical neurons has consequences for the brain’s capacity to integrate information (Fig. 5 and 6). During wakefulness, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) applied to premotor cortex and other cortical areas induces a sustained response (300 ms) involving the sequential activation of specific brain areas, the identity of which depends upon the precise site of stimulation (63, 64). During early non-REM sleep, presumably due to the induction of a local down-state, TMS pulses produce instead a short (<150 ms) local response (64), suggesting a loss of integration. Intriguingly, TMS pulses to mesial parietal regions, overlying the main hub in the cortical connectional core (49), trigger a stereotypic, high-amplitude slow wave closely resembling spontaneous slow waves (63). This stereotypic response, presumably due to the simultaneous activation of the cortical connectional core and to the induction of a global down state, reflects a limited repertoire of activity patterns and thus a loss of information.

Consciousness and integrated information

The evidence from anesthesia and sleep states (Fig. 2–3) converges to suggest that loss of consciousness is associated with a breakdown of cortical connectivity and thus of integration, or with a collapse of the repertoire of cortical activity patterns and thus of information (Fig. 2). Why should this be the case? A recent theory suggests a principled reason: information and integration may be the very essence of consciousness (52). Classically, information is the reduction of uncertainty among alternatives: when a coin falls on one of its two sides, it provides 1 bit of information, whereas a die falling on one of six faces provides ~2.6 bits. But then having any conscious experience, even one of pure darkness, must be extraordinarily informative, since we could have had countless other experiences instead (think of all the frames of every possible movie). Having any experience is like throwing a die with a trillion faces and identifying which number came up (Fig. 2). On the other hand, every experience is an integrated whole that cannot be subdivided into independent components. For example, with an intact brain you cannot experience the left half of the visual field independently of the right half, or visual shapes independently of their color. In other words, the die of experience is a single one throwing multiple dice and combining the numbers will not do.

Less metaphorically, the theory claims that the level of consciousness of a physical system is related to the repertoire of different states (information) that can be discriminated by the system as a whole (integration). A measure of integrated information, called phi (Φ), can be used to quantify the information generated when a system enters one particular state of its repertoire, above and beyond the information generated independently by its parts (52). In practice, Φ can only be measured rigorously for small, simulated systems. However, empirical measures could be devised to evaluate integrated information on the basis of EEG data, resting functional connectivity, or TMS-evoked responses. This approach could allow the development of consciousness monitors that evaluate both loss of integration, as revealed by reduced functional or effective connectivity, and loss of information, as evidenced by stereotypic responses.

This theory has some interesting implications for anesthesia. For example, it explains why a corticothalamic complex is essential for consciousness and is thus the proper target for anesthesia: by conjoining functional specialization (each cortical area and neuronal group within each area is exquisitely specialized) with functional integration (thanks to extensive corticocortical and corticothalamocortical connectivity), a corticothalamic complex is well suited to behave as a single dynamic entity endowed with a large number of discriminable states. By contrast, parts of the brain made up of small, quasi-independent modules, such as the cerebellum, and parallel loops through the basal ganglia, are not sufficiently integrated, which is perhaps why they can be lesioned without loss of consciousness (18, 52). The theory suggests that one should not interpret individual motor responses, or localized activations, as signs of consciousness, and conversely should not interpret the absence of motor responses as a sure sign of unconsciousness. Finally, from this theoretical perspective, consciousness is not an all-or-none property, but it is graded: specifically, it increases in proportion to a system’s repertoire of discriminable states. The shrinking or dimming of the field of consciousness during sedation is consistent with this idea. On the other hand, the abrupt loss of consciousness at a critical concentration of anesthetics suggests that the integrated repertoire of neural states underlying consciousness may collapse non-linearly.

Conclusions

Despite different mechanisms and sites of action, most anesthetic agents appear to cause unconsciousness by targeting, directly or indirectly, a posterior lateral corticothalamic complex centered around the inferior parietal lobe, and perhaps a medial cortical core. Whether the medial or lateral component is more important, and whether anterior cortical regions are critical primarily for executive functions and perhaps self-reflection, remain questions for future work. Second, anesthetics can cause unconsciousness not just by deactivating this posterior corticothalamic complex, but also by producing a functional disconnection between subregions of this complex. Third, although assessing loss of consciousness with verbal commands may usually be adequate, it may occasionally be misleading. Finally, one theoretical framework that seems to fit well with current empirical data suggests that consciousness requires an integrated system with a large repertoire of discriminable states. According to this framework, anesthetics would produce unconsciousness either by preventing integration (blocking the interactions among specialized brain regions) or by reducing information (shrinking the number of activity patterns available to cortical networks). Other frameworks for consciousness, emphasizing access to a global workspace (65, 66), or the formation of large coalitions of neurons (43), are also consistent with many of the findings described here, especially those concerning the role of cortical integration. Altogether, these ideas should help in developing agents with more specific actions, in better monitoring their effects on consciousness, and in employing anesthesia as a tool for characterizing the neural substrates of consciousness.

References and Notes

- 1.Sebel PS, et al. Anesth Analg. 2004 Sep;99:833. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000130261.90896.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkire MT, Miller J. Prog Brain Res. 2005;150:229. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudetz AG. Seminars in Anesthesia, Perioperative Medicine and Pain. 2006;25:196. [Google Scholar]

- 4.John ER, Prichep LS. Anesthesiology. 2005 Feb;102:447. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200502000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mashour GA. Anesthesiology. 2004 Feb;100:428. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200402000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franks NP. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 May;9:370. doi: 10.1038/nrn2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campagna JA, Miller KW, Forman SA. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 22;348:2110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004 Sep;5:709. doi: 10.1038/nrn1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ries CR, Puil E. J Neurophysiol. 1999 Apr;81:1795. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llinas RR, Steriade M. J Neurophysiol. 2006 Jun;95:3297. doi: 10.1152/jn.00166.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steriade M, Timofeev I, Grenier F. J Neurophysiol. 2001 May;85:1969. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voss L, Sleigh J. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007 Sep;21:313. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobson JA, Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R. Behav Brain Sci. 2000 Dec;23:793. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x00003976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topulos GP, Lansing RW, Banzett RB. J Clin Anesth. 1993;5:369. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(93)90099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker MR, Hann JR, Phillips CL. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984 Oct;42:668. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langsjo JW, et al. Anesthesiology. 2005 Aug;103:258. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkire MT, Gruver RL, Langsjo JW, Kaisti K, Scheinin H. Anesthesiology. 2007;104:A1219. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posner JB, Plum F. Contemporary neurology series. 4. Oxford University Press; Oxford ; New York: 2007. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma; p. xiv.p. 401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen AM, et al. Science. 2006 Sep 8;313:1402. doi: 10.1126/science.1130197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veselis RA, Reinsel RA, Feshchenko VA, Dnistrian AM. Anesthesiology. 2002 Aug;97:329. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell IF, Wang M. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:3. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wijdicks EF. N Engl J Med. 2001 Apr 19;344:1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:847. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200604000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, Forbes A, Chan MT. Lancet. 2004 May 29;363:1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider G, Gelb AW, Schmeller B, Tschakert R, Kochs E. Br J Anaesth. 2003 Sep;91:329. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller JW, Ferrendelli JA. Neuropharmacology. 1990 Jul;29:649. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90026-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alkire MT, McReynolds JR, Hahn EL, Trivedi AN. Anesthesiology. 2007 Aug;107:264. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270741.33766.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laureys S, Boly M, Maquet P. J Clin Invest. 2006 Jul;116:1823. doi: 10.1172/JCI29172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiff ND, et al. Nature. 2007 Aug 2;448:600. doi: 10.1038/nature06041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkire MT, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb 5;105:1722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711651105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alkire MT, Haier RJ, Fallon JH. Conscious Cogn. 2000 Sep;9:370. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1999.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiff ND, Plum F. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2000 Sep;17:438. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200009000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vahle-Hinz C, Detsch O, Siemers M, Kochs E. Exp Brain Res. 2007 Jan;176:159. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0604-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angel A. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:148. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.French JD, Hernandez-Peon R, Livingston RB. J Neurophysiol. 1955 Jan;18:74. doi: 10.1152/jn.1955.18.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakakimura K, Sakabe T, Funatsu N, Maekawa T, Takeshita H. Anesthesiology. 1988 May;68:777. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198805000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villablanca J, Salinas-Zeballos ME. Arch Ital Biol. 1972 Oct;110:383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velly LJ, et al. Anesthesiology. 2007 Aug;107:202. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270734.99298.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magnin M, Bastuji H, Garcia-Larrea L, Mauguiere F. Cereb Cortex. 2004 Aug;14:858. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guillery RW, Sherman SM. Neuron. 2002 Jan 17;33:163. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White NS, Alkire MT. Neuroimage. 2003 Jun;19:402. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones EG. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002 Dec 29;357:1659. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crick F, Koch C. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:119. doi: 10.1038/nn0203-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veselis RA, et al. Anesth Analg. 2004 Aug;99:399. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Markowitsch HJ, Kessler J. Exp Brain Res. 2000 Jul;133:94. doi: 10.1007/s002210000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaisti KK, et al. Anesthesiology. 2002 Jun;96:1358. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200206000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blumenfeld H. Prog Brain Res. 2005;150:271. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50020-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maquet P. J Sleep Res. 2000 Sep;9:207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagmann P, et al. PLoS Biol. 2008 Jul 1;6:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vogeley K, et al. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004 Jun;16:817. doi: 10.1162/089892904970799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gyulai FE, Firestone LL, Mintun MA, Winter PM. Anesth Analg. 1996 Aug;83:291. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199608000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tononi G. BMC Neurosci. 2004 Dec 2;5:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-5-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Imas OA, Ropella KM, Wood JD, Hudetz AG. Neurosci Lett. 2006 Jul 24;402:216. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crick FC, Koch C. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005 Jun 29;360:1271. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Munglani R, Andrade J, Sapsford DJ, Baddeley A, Jones JG. Br J Anaesth. 1993 Nov;71:633. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imas OA, Ropella KM, Ward BD, Wood JD, Hudetz AG. Neurosci Lett. 2005 Oct 28;387:145. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hudetz AG. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2008 Summer;46:25. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e3181755db5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Super H, Spekreijse H, Lamme VA. Nat Neurosci. 2001 Mar;4:304. doi: 10.1038/85170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steyn-Ross ML, Steyn-Ross DA, Sleigh JW, Wilcocks LC. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2001 Jul;64:011917. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.011917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hudetz AG, Imas OA. Anesthesiology. 2007 Dec;107:983. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000291471.80659.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kroeger D, Amzica F. J Neurosci. 2007 Sep 26;27:10597. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3440-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103:1268. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Massimini M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 May 15;104:8496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702495104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Massimini M, et al. Science. 2005 Sep 30;309:2228. doi: 10.1126/science.1117256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baars BJ. Prog Brain Res. 2005;150:45. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dehaene S, Sergent C, Changeux JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Jul 8;100:8520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332574100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.GT has a patent pening on the use of TMS-EEG in anesthesia