Abstract

Sexual well-being after breast cancer recurrence has received little clinical attention. In discussing the sexual difficulties after recurrence we draw upon our longitudinal studies of newly diagnosed patients. It is noted that sexuality declines after a patient’s initial diagnosis and treatment, with further decline after recurrence. However, data suggest that couples strive to maintain intimacy as the health of the patient falters, providing further evidence of the resilience of patients coping with a worsened prognosis.

Keywords: breast cancer recurrence, intimacy, sexual difficulties

Longitudinal study of patients with recurrence suggests that multiple aspects of life are initially disrupted1 and may remain impaired for months.2 Decades ago Silberfarb et al3 noted the sexual difficulties of those with recurrence. They interviewed 52 women with recurrent but stable disease, 59 with recurrent, end-stage disease, and 50 with initial diagnoses. Patients with recurrent disease were 50% more likely to experience significant disruptions in sexual desire and frequency of coitus than were their newly diagnosed counterparts. In the ensuing 30+ years, few studies of patients coping with recurrence have been conducted in comparison with many studies with the initially diagnosed, with no further examination of sexuality, except one report.4 The dearth of data may be due to the assumption that, in the context of recurrence, sexuality might be the least of a patient’s concerns. However, heightened symptomatology, treatment side effects, and impaired functional status adversely affect sexual activity, desire, and responding for women with cancer.5 More recently, we have contributed empirical studies from patients coping with breast cancer recurrence. We will quickly summarize these findings. However, new data will show the sexual responses of patients before their recurrence diagnosis and their responses thereafter. In combination, these data detail the struggles of breast cancer patients coping with the sexual changes that inevitably occur with cancer diagnosis.

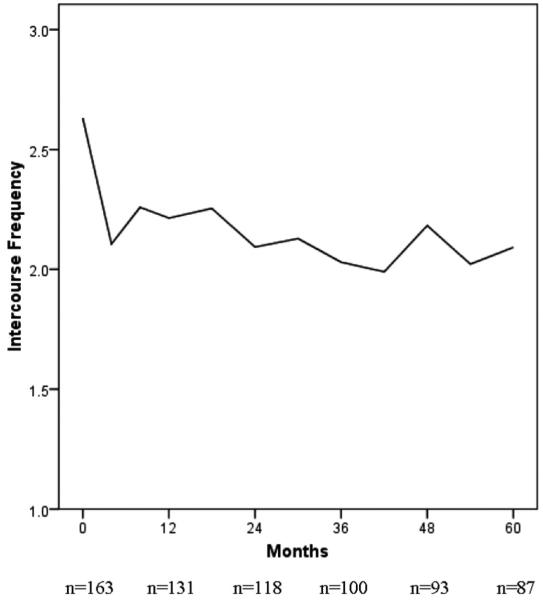

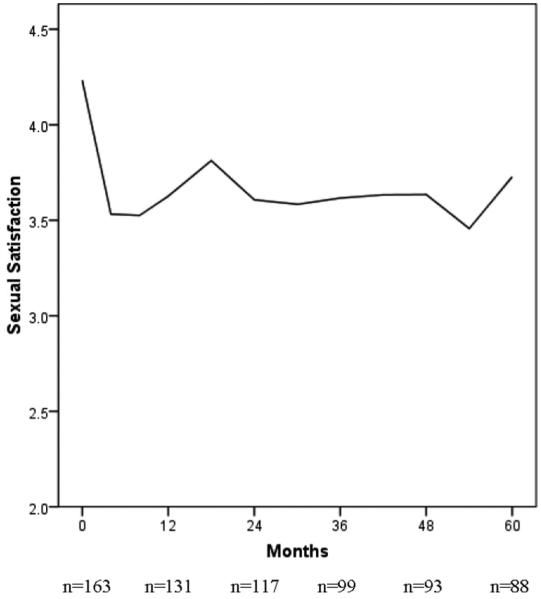

Before discussing recurrence, we note that the initial breast cancer diagnosis and the ensuing treatments introduce significant sexual changes. There is an extensive literature on the sexual morbidities after breast cancer, most of which focuses on the newly diagnosed coping with mastectomy and adjuvant treatments. For them, there is an immediate reduction in sexual activity and responsiveness that we6 and others7-9 have noted. Unfortunately, this disruption does not, for the majority, resolve. In Figures 1 and 2 we provide data for 163 patients followed longitudinally [see Stress and Immunity Breast Cancer Project (SIBCP) description below]. Those with partners provided estimates of the frequency of sexual intercourse (Fig. 1) and their global evaluation of their sexual life (Fig. 2) for the 2 months before diagnosis. Assessments were then repeated every 6 months for the next 5 years. Before diagnosis, patients reported the frequency of intercourse being approximately once per week, as shown in Figure 1. The frequency dropped by one half (1-2 times per month) when chemotherapy was initiated, and during the 5 years that followed there was no return to pre-cancer levels and little improvement overall. The same trajectory is found with data on sexual satisfaction provided in Figure 2. The level falls from a rating that is above average (4) before diagnosis and below average, thereafter. Thus, sexuality has already significantly changed when recurrence occurs.

FIGURE 1.

Reports of intercourse frequency by partnered women with breast cancer (N = 163) at diagnosis and across 5 years of follow-up. The initial data point indicates patients’ retrospective estimate of intercourse frequency for the 2 months before diagnosis.

FIGURE 2.

Global evaluations of sexual life from partnered women with breast cancer (N = 163) at diagnosis and across 5 years of follow-up. The initial data point indicates patients’ retrospective evaluation for the 2 months before diagnosis.

PSYCHOLOGIC RESPONSES TO RECURRENCE DIAGNOSIS

Our descriptive studies of patients with breast cancer recurrence come from 2 sources. The first (sample I) are patients (N = 227) followed from a prior randomized clinical trial (SIBCP) testing the effectiveness of a psychologic intervention to reduce the risk for breast cancer recurrence and death. Patients were randomized to either intervention and assessment or assessment only study arms. Previously reported, the intervention produced significant gains across secondary outcomes [distress, social adjustment, health behaviors (diet and smoking cessation), treatment adherence, and health] and enhanced T-cell immunity.10,11 After a mean of 11 years of follow-up, intervention patients had a reduced risk of disease progression, ie, breast cancer recurrence (hazard ratio, 0.55, P = 0.034) and death from breast cancer (hazard ratio, 0.44, P = 0.016).12

All patients were followed for upward of 13 years, including those who were subsequently diagnosed with recurrence. These data provided for the following recurrence studies: (a) prospective (ie, before recurrence) longitudinal analyses; (b) repeated measures studies comparing the responses of individuals to their initial and recurrence diagnoses; and (c) comparison of those with recurrence with matched trial participants who did not recur. Our discussion is also informed by accrual of a second sample (II), who did not participate in the trial but who were recently diagnosed with breast cancer recurrence (N = 80) and also followed longitudinally.

We have previously reported that at recurrence cancer-related traumatic stress symptoms are significant, much like they are at the initial diagnosis.13 We compared patients’ biobehavioral data (stress, distress, quality of life, physical functioning, and physical symptoms) at recurrence to their own data from the initial diagnosis.14 We studied the first 30 patients in the trial who recurred and analyses showed that cancer-specific stress for the 2 diagnoses was equivalent.

These findings were extended.15 Patients with newly diagnosed recurrent (n = 69) or initial (n = 113) breast cancer were compared. All patients were assessed shortly after diagnosis (baseline) and 4, 8, and 12 months later. Mixed-effects models with appropriate sociodemographic, disease, and cancer treatment controls were conducted. Replicating the previous study, all patients—initial or recurrence diagnosis—had comparable, high levels of cancer-specific stress and stress levels equivalent to those of patients seeking psychiatric treatment for anxiety disorders. Although cancer-related stress declined, it remained at or above the clinical cutoff for patients as long as 8 months after diagnosis. In contrast, general stress showed a trend to decline more quickly for recurrence patients. These data suggest a shift in the experience of the stress after cancer diagnosis. That is, patients’ learn to cope and general feelings of stress decline but patients do not acclimate to the trauma of the diagnosis itself. Another important difference between the samples was the treatment and symptom context. After an initial breast cancer diagnosis, adjuvant treatment is completed within the next 6 to 8 months, but recurrence patients often receive medical treatments through the next 12 months. We found that patients with recurrence experienced greater fatigue and slower recovery over the year of follow-up.

Recurrence may also be remarkable by patients’ heightened risk for depressive symptoms. In surveys, both dated and recent, it is estimated that 30% to 50% of cancer patients meet criteria for mood or anxiety disorders,16 with depression being the most common.17 Estimates for major depressive disorder are 22% to 29% for patients with early stage (stage I) disease,18 upwards of 40% for patients with advanced disease (stage II/III or IV),16 and the rates increase further with recurrence.19 We examined predictors of depressive symptoms in women diagnosed with a recurrence.20 Patients (N = 67) were assessed at diagnosis and 4 months later. Controlling for physical symptoms and baseline depression, hopelessness at diagnosis was a significant predictor of the maintenance of depressive symptoms. Also, structural social support (ie, presence/absence of a romantic partner) was also important and interacted with hopelessness. That is, women feeling hopelessness and who were alone (ie, without a partner) were especially vulnerable to depressive symptoms. In summary, the diagnosis and treatment for an initial diagnosis of cancer can be seen as a series of time-limited stressors, whereas stress with recurrence is chronic. The experience of recurrence is qualitatively different from that of the initial diagnosis.

FROM HEALTH TO SICKNESS: SEXUAL CHANGES WITH RECURRENCE

We have previously reported data comparing breast cancer patients with recurrence (R; n = 60) assessed at diagnosis (baseline) and 4-, 8-, and 12-months later compared with patients who remained disease-free (DF; n = 120) and matched to R sample on age, stage of disease at initial diagnosis, and duration of follow-up.21 Using linear mixed modeling, group comparison revealed differences in their trajectories of change on measures of sexuality, relationship satisfaction, cancer-specific stress, and physical functioning. Data showed that the R group at baseline had significantly lower intercourse frequency and physical functioning compared with the DF group and these differences were maintained though the period of follow up. There were no significant differences in the frequencies of kissing or sexual and relationship satisfaction. Sexual changes were notable for younger patients. These data provided the first longitudinal and the first controlled study of sexuality for women coping with recurrence.

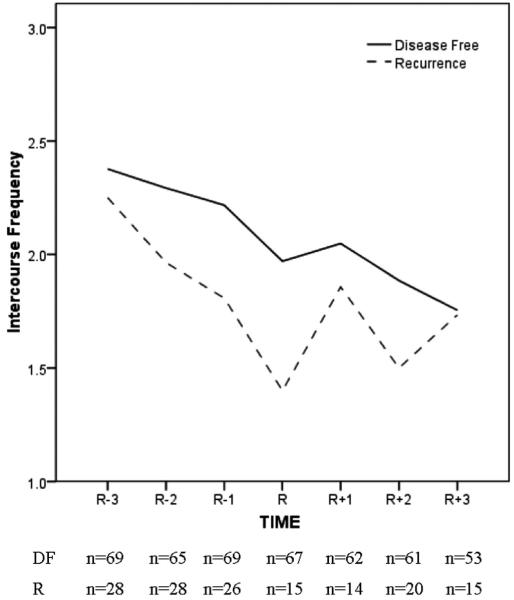

We provide here a more detailed look at the sexuality trajectory of recurrence. SIBCP patients (N = 123) who recurred (R; n = 41) were matched to patients remaining DF (n = 82) on demographic and prognostic characteristics, duration of DF follow-up, and study arm. A unique perspective is offered. Namely, we display the sexual trajectory of patients 18, 12, and 6 months before recurrence diagnosis and the trajectory 4, 8, and 12 months after the recurrence diagnosis. Equivalent time points for the DF group are provided for reference.

Of the 123, data from the patients who had partners and completed sexuality measures were analyzed and sample sizes at each time point are reported in the figures. Figure 3 displays data for the frequency of intercourse. Both groups reported a frequency equivalent to twice per month at 18 months (R - 3). However, at recurrence diagnosis (R), intercourse frequency for the R group declined to less than once per month whereas the DF group maintained their level of intercourse frequency. During the subsequent months, intercourse frequency for the R group increased and eventually reached to that of the DF group by 12 months (R + 3). Similar trajectories were observed for sexual satisfaction (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Frequency of sexual intercourse reported by partnered women diagnosed with recurrence (R; n = 28) at time R. A matched sample of partnered women previously diagnosed with breast cancer who remained DF (n = 69) is provided. A timeline relevant for the R group is used. R - 3, R - 2, and R - 1 correspond to 18, 12, and 6 months before the recurrence diagnosis, with R, R + 1, R + 2, and R + 3 corresponding to the time of recurrence diagnosis and 4, 8, and 12 months after diagnosis. Equivalent disease-free follow-up time points for the DF are used.

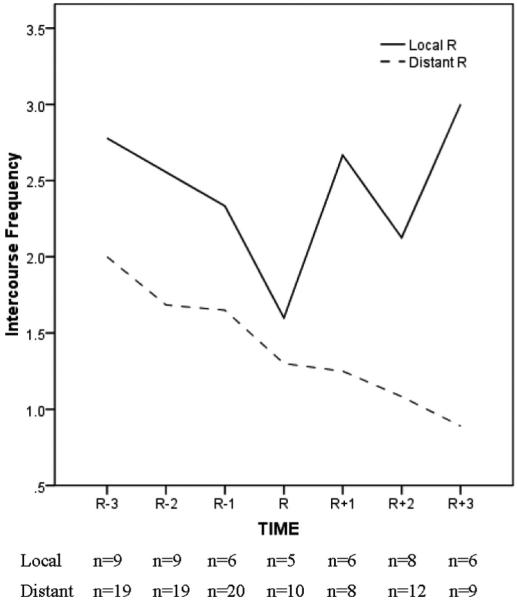

However, the view of DF and R group equivalence at 12 months (R + 3) is moderated by the extent of disease for the recurrence patients. Figure 4 shows data for the R group only and reveals that the trajectory of improvement in intercourse frequency (and sexual satisfaction) at 12 months (R + 3) in Figure 3 occurred primarily among patients with localized disease (32%), as there was a steady decline in intercourse frequency for patients with distant metastases (68%). At 12 months after recurrence (R + 3), both intercourse frequency and sexual satisfaction were significantly higher for the patients with a local recurrence than the patients with distant metastases (Ps < 021).

FIGURE 4.

Frequency of sexual intercourse reported by partnered women with recurrent breast cancer (N = 28), contrasting patients with localized (n = 9) and distant (n = 19) metastases. R - 3, R - 2, and R - 1 indicate 18, 12, and 6 months before recurrence diagnosis and R, R + 1, R + 2, and R + 3 indicate recurrence diagnosis and 4, 8 and 12 months after diagnosis, respectively.

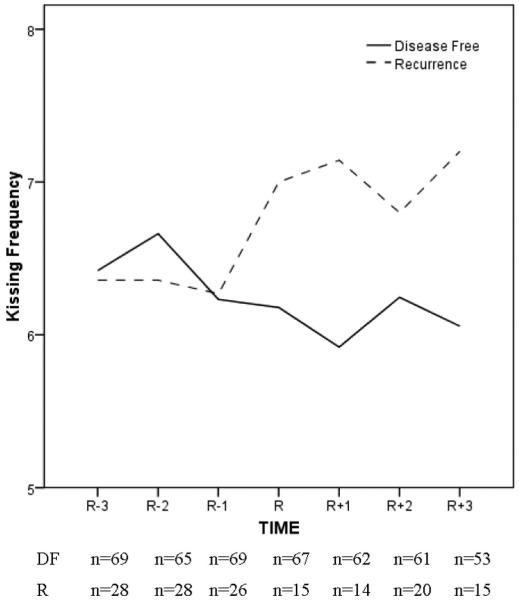

The data also revealed an important perspective on intimacy among couples. When intercourse (or an equivalent activity) becomes difficult or impossible, the need for affection and intimacy remains. The stress of recurrence is great, both for the patient and partner. The prospect of losing one’s spouse is one of the most stressful events that can be experienced.22,23 Given and Given24 found that caregivers, primarily partners of women with recurrent breast cancer, had more depressive symptoms than caregivers of patients with newly diagnosed cancer; depressive symptoms also increased across time. Thus, as both individuals are struggling with recurrence, our data on the frequency of kissing conveys an important message (Fig. 5). With illness, intercourse becomes more difficult for many, but the need for affection remains, and couples respond with an immediate and steady increase in the frequency of kissing after recurrence diagnosis (ie, R to R + 3).

FIGURE 5.

Frequency of kissing reported by partnered women diagnosed with breast cancer recurrence (R; n = 28). A matched sample of partnered women previously diagnosed with breast cancer who remained DF (n = 69) is provided. A timeline relevant for the R group is used. R - 3, R - 2, and R - 1 correspond to 18, 12, and 6 months before the recurrence diagnosis, with R, R + 1, R + 2, and R + 3 corresponding to the time of recurrence diagnosis and 4, 8, and 12 months after diagnosis. Equivalent disease-free follow-up time points for the DF are used.

SUMMARY

In conclusion, we provide empirical detail on the trajectory of sexuality in the months leading to and after diagnosis of breast cancer recurrence. General health plays a major role in the extent to which women can maintain a sexual life. We previously reported that younger patients might be most vulnerable to sexual disruption as are patients with disseminated disease. Women coping with recurrence are attempting to maintain their quality of life and physical and emotional intimacy with their partner. The evidence suggests that they are able to do so despite the chronic stress and ongoing health challenges of recurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks the patients for their continuing support, Dr. Hae-Chung Yang, and the research staff of the Stress and Immunity Cancer Projects.

Supported in part by the American Cancer Society (PBR-89, RSGPB-03-248-01-PBP), Longaberger Company-American Cancer Society Grant for Breast Cancer Research (PBR-89A), National Institutes of Mental Health (RO1 MH51487), the National Cancer Institute (KO5 CA098133; RO1 CA92704), and The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA16058).

REFERENCES

- 1.Oh S, Heflin L, Meyerowitz BE. Quality of life of breast cancer survivors after a recurrence: a follow-up study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;87:45–57. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000041580.55817.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornton AA, Madlensky L, Flatt SW, et al. The impact of a second breast cancer diagnosis on health related quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-1411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silberfarb PM, Maurer LH, Crouthamel CS. Psychosocial aspects of neoplastic disease. I. Functional status of breast cancer patients during different treatment regimens. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:450–455. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson Frost M, Suman VJ, Rummans TA, et al. Physical, psychological and social well-being of women with breast cancer: the influence of disease phase. Psychooncology. 2000;9:221–231. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<221::aid-pon456>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolberg WH, Romsaas EP, Tanner MA, et al. Psychosexual adaptation to breast cancer surgery. Cancer. 1989;63:1645–1655. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890415)63:8<1645::aid-cncr2820630835>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yurek D, Farrar W, Andersen BL. Breast cancer surgery: comparing surgical groups and determining individual differences in postoperative sexuality and body change stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:697–709. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.68.4.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz P, Rowland JH, Desmond KA, et al. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, et al. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2371–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henson H. Breast cancer and sexuality. Sexuality Disability. 2002;20:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: a clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3570–3580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, et al. Distress reduction from a psychological intervention contributes to improved health for cancer patients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:953–961. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen BL, Yang H-C, Farrar WB, et al. Psychological intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2008;113:3450–3458. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, et al. Stress and immune responses after surgical treatment for regional breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:30–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen BL, Shapiro CL, Farrar WB, et al. Psychological responses to cancer recurrence: a controlled prospective study. Cancer. 2005;104:1540–1547. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H-C, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, et al. Surviving recurrence: psychological and quality of life recovery. Cancer. 2008;112:1178–1187. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zabora JR, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, et al. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raison CL, Miller AH. Depression in cancer: new developments regarding diagnosis and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:283–294. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, et al. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. Br Med J. 2005;330:1–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotopf M, Chidgey J, Addington-Hall J, et al. Depression in advanced disease: a systematic review, Part 1: Prevalence and case finding. Palliat Med. 2002;16:81–97. doi: 10.1191/02169216302pm507oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brothers BM, Andersen BL. Hopelessness as a predictor of depressive symptoms for cancer patients coping with recurrence. Psychooncology. 2008 doi: 10.1002/pon.1394. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen BL, Carpenter KM, Yang H-C, et al. Sexual well-being among partnered women with breast cancer recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3151–3157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chekryn J. Cancer recurrence: personal meaning, communication, and marital adjustment. Cancer Nurs. 1984;7:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis FM, Deal LW. Balancing our lives: a study of the married couple’s experience with breast cancer recurrence. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:943–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Given B, Given CW. Patient and family caregiver reaction to new and recurrent breast cancer. JAMA. 1992;47:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]