Abstract

Cancer stem cells are defined as the unique subpopulation in the tumors that possess the ability to initiate tumor growth and sustain self-renewal as well as metastatic potential. Accumulating evidence in recent years strongly indicate the existence of cancer stem cells in solid tumors of a wide variety of organs. In this review, we will discuss the possible existence of a gastric cancer stem cell. Our recent data suggest that a subpopulation with a defined marker shows spheroid colony formation in serum-free media in vitro, as well as tumorigenic ability in immunodeficient mice in vivo. We will also discuss the possible origins of the gastric cancer stem cell from an organ-specific stem cell versus a recently recognized new candidate bone marrow–derived cell (BMDC). We have previously shown that BMDC contributed to malignant epithelial cells in the mouse model of Helicobacter-associated gastric cancer. On the basis of these findings from animal model, we propose that a similar phenomenon may also occur in human cancer biology, particularly in the cancer origin of other inflammation-associated cancers. The expanding research field of cancer stem-cell biology may offer a novel clinical apparatus to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Interest in gastric cancer stem cells (CSCs) has arisen in the broader context of the CSC hypothesis, which first appeared more than a century ago when a number of European pathologists observed that tumors were composed of a heterogeneous mixture of partially differentiated cell types, similar in many respects to a normal organ.1 The laboratory group led by John E. Dick first demonstrated the existence of CSCs more than a decade ago, when they proved the hypothesis to be largely true for human acute myeloid leukemia.2,3 The leukemic stem cell, which was defined as specific markers of CD34+/CD38−, could serially reproduce the disease in immunodeficient mice (eg, nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency [SCID] mice), and it was consistent with their properties of longevity and self-renewal. Despite some limitations, the growth of tumor cells with defined markers in immunodeficient mice has become the gold standard for identifying a CSC4 in other solid tumors such as breast cancer,5 brain cancer,6 prostate cancer,7 melanoma,8 colon cancer,9-11 liver cancer,12 pancreatic cancer,13,14 and head and neck cancer.15 In these studies, as few as 100 cells of CSC subpopulation showed better growth in immunodeficient mice compared to non-CSC subpopulation. At a recent American Association for Cancer Research workshop, a working group used the available data to create a consensus definition of the CSC as “cells within a tumor that possess the capacity for self-renewal and that can cause the heterogeneous lineages of cancer cells that constitute the tumor.”16

The majority of studies that have looked at human tumor cells transplanted into immunodeficient mice have demonstrated the existence of rare CSCs in a variety of solid tumors. Nevertheless, a recent article has provided the evidence that in mouse-to-mouse transplantation using pre-B/B lymphoma cells from Eμ-myc transgenic mice, the majority of cells within the murine tumors retain the CSC phenotype.17 The authors suggest that rarity of CSCs found in human cancers may result from species-mismatch in a xenograft transplantation. It is possible that the immunodeficient mouse may not provide the ideal local environment for the growth of human cancer cells, thus creating the false impression that tumor-initiating cells are rare.18 Another weakness of current support for the CSC hypothesis is that the markers used to purify the CSCs are not highly specific, and, in most cases, the CSCs have not perfectly been purified. Despite these limitations, there is a growing consensus that many cancers can be viewed as differentiated tissues, and only CSCs are able to sustain and propagate tumors and give rise to invasive lesions and metastases. This new paradigm has remarkable implications for cancer therapy because our current therapies are more successful in eradicating non-CSCs than CSCs.19 The purification and characterization of CSCs could lead to the identification of better targets for therapeutic interventions. With regard to gastric cancer, studies have not yet defined and characterized CSCs, and first we briefly review the classification and etiology of gastric cancer.

ETIOLOGY OF GASTRIC CANCER

Gastric cancer represents roughly 2% (25,500) of all new cancer cases yearly in the United States. However, gastric cancer is much more common in many parts of the world (eg, East Asia and South America). Worldwide, it is the fourth most common cancer and the second highest cause of cancer-related mortality (1 million deaths per year) after lung cancer.20,21 The male predominance (male-to-female ratio of 2:1) is consistent across many geographic regions. Epidemiologic studies indicate that gastric cancer is associated with a high-salt diet, smoking, and a low intake of fruits and vegetables.22 Nevertheless, the strongest causal association with this disease is clearly infection with the gastric-specific pathogen Helicobacter pylori (H pylori). Abundant evidence demonstrates that H pylori infection is the primary risk factor for noncardia gastric cancer, responsible for at least two thirds of cases. On the primary basis of early epidemiologic studies, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (a branch of WHO) in 1994 classified H pylori as a class I carcinogen.23,24 However, with respect to proximal gastric tumors, commonly known as the cardia type of gastric cancer, conflicting data have been reported with respect to the association with H pylori. Kamangar et al25 conducted a prospective nested case-control study based on H pylori serologies and concluded that H pylori is a strong risk factor for noncardia gastric cancer, but is inversely associated with the risk of gastric cardia cancer. In addition to H pylori infection, Epstein-Barr virus has been detected in stomach tissues in approximately 10% of gastric carcinoma cases in some parts of the world.26

Noncardia gastric cancer has been classified under the Lauren system into two histologic types: intestinal and diffuse. Intestinal-type gastric cancer usually occurs at a late age, is more common in men, and progresses through a relatively well-defined series of preneoplastic histologic steps.27 Diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma more commonly affects younger people, affects men and women nearly equally, and consists of individually infiltrating neoplastic cells that do not form glandular structures and are not associated with intestinal meta-plasia. Of note, most cases of familial gastric cancer exhibit a diffuse histopathology, and mutations in the E-cadherin (CDH-1) gene are reported to be a major cause of this disease.28 Although H pylori significantly increases the risk of developing both subtypes of gastric cancer, the mechanisms of the development of intestinal-type cancer are more well-characterized. Therefore, the remainder of this review will focus predominantly on the origins of intestinal-type gastric cancer and its relationship to H pylori infection.

Intestinal-type gastric cancer typically arises in the setting of chronic gastritis and develops through intermediate stages of atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally gastric cancer. This lengthy process, known commonly as the Correa pathway, is dependent on continued chronic inflammation.29,30 In addition to classical intestinal metaplasia, numerous studies have also pointed to spasmolytic peptide expressing metaplasia, a lesion positive for trefoil factor 2 expression, as a precursor of gastric cancer. Metaplasia is a particularly interesting feature because it is a fairly permanent alteration that suggests a marked change in the genetic and epigenetic program of the gastric stem or progenitor cells.

In the past, inflammation was thought to have an essential role in tumor promotion, but not in initiation, to stimulate their growth and enhance their further progression to cancer. Chronic inflammation induces increased tissue turnover, which is thought to predispose to an excessive rate of proliferation, and in many cases results in more frequent mitotic errors and an increased rate of mutagenesis. Notably, Matsumoto et al31,32 recently reported that H pylori infection of the gastric epithelium induced the expression of the activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) gene, a gene originally linked to immunoglobulin class switching and B lymphocyte hypermutation, but aberrantly expressed in cancer, where it may predispose to point mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Although the mutagenesis of specific genes is certainly of some importance in carcinogenesis, recent studies have highlighted important roles for specific immune cell populations (eg, macrophages, T cells) and proinflammatory cytokines (eg, interleukin[IL]-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α) in the pathogenesis of cancer.20,33 Given the current hypothesis that cancer arises from CSCs, the mechanism by which chronic inflammation leads to the emergence of CSCs needs to be addressed.

WHAT IS THE EVIDENCE FOR A GASTRIC CSC?

As briefly discussed in the first section, accumulating data support that CSCs exist for many solid tumors. However, clear evidence has not yet been reported for a number of other major organs. Although a comprehensive characterization of gastric CSCs have not yet been reported, we present some preliminary data addressing the issue in this review.34

Two different approaches have typically been used to identify CSCs in published studies.35,36 One is an in vitro method termed “spheroid colony formation,” and another is in vivo method involving implantation of candidate CSCs under the skin or within organ-specific sites (eg, orthotopic) of immunodeficient mice (eg, SCID mice, Rag2/γC double-mutant mice). The former method involves culturing candidate CSCs in culture dishes specially coated for noncell attachment with serum-free media containing only epidermal growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor. The growth of spherical colonies after a few weeks is considered indicative of self-renewal ability, and would be consistent with a CSC phenotype. The latter method—growth of cells in immunodeficient mice—is needed to demonstrate true tumorigenicity and is generally regarded as the gold standard for proving existence of CSC, despite the limitations of this technique as described herein. A number of studies have suggested that these two approaches generally provide similar results in evaluating candidate CSCs for many solid tumors.35,36

We have recently analyzed a number of human gastric cancer cell lines using these methods.34 As shown in Table 1, after in vitro culture for a few weeks in serum-free media under nonadherent conditions, some of the cancer cell lines produced spheroid colonies. We also performed implantation of these cells subcutaneously into SCID mice, and many of the mice had skin tumors a few months later (Fig 1). Notably, we confirmed for each gastric cancer cell line that the ability of spheroid colony formation correlated perfectly with the tumorigenicity in SCID mice. Taken together, these studies strongly support the supposition that some gastric cancer cell lines contain cells with a CSC phenotype.

Table 1.

Cell-Surface Marker Expression and Tumorigenicity of Human Gastric Cancer Cell Lines

| Surface Marker |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line | (a) | (b) | (c) | Spheroid | Tumorigenicity |

| (1) | + | + | − | + | + |

| (2) | + | + | − | + | + |

| (3) | + | + | − | − | ± |

| (4) | ± | − | + | − | − |

NOTE. Spheroid positivity means the cells produced spheroid colonies with serum-free medium in nonattachment cell plates. Tumorigenicity positivity means the cells produced skin tumor in immunodeficient mice such as severe combined immunodeficiency mice or Rag2/γC double-knockout mice. Tumorigenicity positivity/negativity means tumors appeared only in Rag2/γC double-knockout mice.

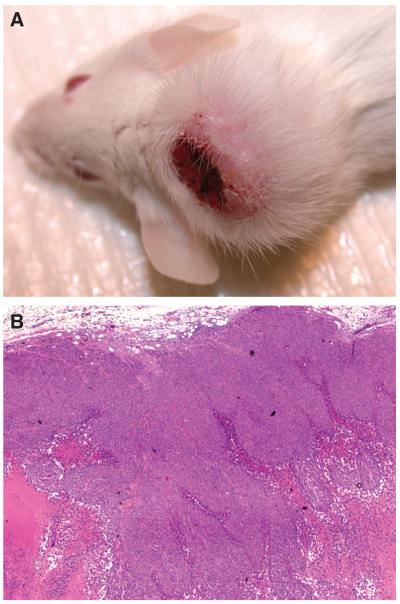

Fig 1.

(A) Skin tumor created by human gastric cancer cell line 1 in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse. Human gastric cancer cell line 1 (500,000 cells/site) was subcutaneously injected into SCID mice. A few months later, injected cells produced skin tumor. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (magnification, 40×).

Next, we investigated the possibility of the expression of candidate cell surface markers as CSCs by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence-activated cell-sorting analysis. As shown in Table 1, the expression pattern of cell surface markers varied among the different cell lines, but one of the markers, (a), was well correlated with in vivo tumorigenicity.34 On the basis of these findings, we fractionated these cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and found that the positive cellular fraction could generate spheroids in culture, whereas the negative fraction produced few or no colonies. Among the positive cell fraction, we could estimate that the spheroid-forming cell population resided within 1% to 10% of the positive cell fraction. In contrast, other potential CSC markers did not show any differences between positive and negative fractions in spheroid colony assay.

In parallel with the afore-described experiments, we also implanted purified cell populations subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice, and found that the marker (a)−positive fraction could generate tumors whereas the negative fraction could not (data not shown). This rather striking difference between the positive and negative cellular fractions was entirely consistent with the result of our spheroid formation assay for each individual cell line. We also tested fractionated cells sorted by other candidate markers in our immunodeficient mice, but found no difference in tumorigenicity with these other markers.

Taken together, these results strongly support the existence of gastric CSCs. Of note, we have also fractionated human gastric cancer cell lines for resistance to chemotherapeutic agents such as such as fluorouracil and paclitaxel, and found a great survival among the CSC marker-positive group (data not shown). Studies using gastric cancer cells from fresh specimens are currently underway.

GASTRIC CANCER ORIGINATES FROM BONE MARROW–DERIVED CELLS

Although preliminary studies have pointed to the existence of gastric CSCs, the origin of these CSCs and their link to inflammation remains an important issue. Understanding the source and genesis of gastric CSCs might facilitate new approaches for prevention and treatment of gastric cancer. For many years, resident tissue stem cells have been viewed as the best candidate for CSCs, because the simplest model is one in which a tumor arises from stem or progenitor cells at the existing site. Some advances have been made in the characterization of adult tissue stem cells during the last decade, but the most notable success has been with hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse37 and human.38 Additional advances have included the isolation of neural stem cells, with several groups simultaneously reporting the isolation and identification of multipotent progenitor cells from the CNS of both mice and humans.39 In terms of digestive organs, progenitor cells from the mouse liver have been described,40 and potential markers for murine intestinal stem cell, such as the orphan G-protein–coupled receptor Lgr5 (another name, Gpr49), have been reported.41

The gastric stem cell has yet to be identified, but historically was long ago predicted based on morphologic studies.42-45 The gastric mucosa is lined by an epithelium that is continually renewed and likely sustained by a population of multipotent stem cells. The stomach mucosa can be divided into two types of epithelium: the oxyntic mucosa, located in the proximal part of the stomach termed as “corpus,” and the distal part of the stomach, which has been termed the “antrum.” The corpus consists of several different cell lineages: (1) surface mucous cells that produce the gastric mucin (eg, mucin 5ac), which protects epithelium from injury (eg, by drugs, alcohol, and foods); (2) parietal cells, which produce protons (H+) as main source of gastric acid; (3) chief cells which contain zymogenic units and, in humans, secrete the digestive enzyme pepsinogen, which is to be cleaved and converted to an active form of pepsin; and (4) endocrine cells, which make a variety of hormones (eg, somatostatin and leptin) as well as histamine. The gastric antrum has a more simple composition and consists of fewer cell types that include mucous cells and endocrine cells (eg, somatostatin, gastrin). It has been presumed that the gastric stem or progenitor cell is located in the isthmus of the gastric glands in the corpus, and gives rise to differentiated daughter cells via bidirectional migration patterns. In the gastric antrum, the stem or progenitor cells are located at the bottom of the glands, and descendents migrate toward the surface unidirectionally.

Bjerknes and Cheng46 first provided the evidence for the existence of multipotent stem cells in the adult mouse gastric epithelium using chemical mutagenesis to label random epithelial cells by loss of transgene function in Rosa26-lacZ transgenic mice that express β-galactosidase gene in a whole body under Rosa26 locus. Their work described that many gastric glands showed a loss of transgene function in all major epithelial cell types, consistent with clonal expansion of a single mutation, therefore indicating the existence of multipotent gastric stem cells. Possible gastric progenitor cells are recently reported to be marked by a 12.4-Kb villin-1 promoter/enhancer fragment. Using the villin-1 promoter upstream of lacZ, EGFP and Cre, rare cells in the gastric glands are labeled by the transgene and shown to give rise to multiple gastric cell lineages in the gland.47 Barker et al41 also reported orphan G-protein–coupled receptor Lgr5 was expressed in the bottom of gastric glands, and their ongoing lineage tracing experiments implied that the entire gastric gland derived from Lgr5-positive cells.

Although gastric stem or progenitor cells might seem to be good candidates for gastric CSCs, another possible source for CSCs has recently been described by our group. These are the bone marrow–derived cells (BMDCs) identified during the course of studies employing mouse models of Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer.48 Bone marrow–derived stem cells possess perhaps a wider range of plasticity and tend to migrate through peripheral organs as a result of inflammation and tissue injury. The differentiation pattern and growth regulation of these cells may depend largely on local environmental signals and cues.49-51 Previous studies have shown that bone marrow–derived endothelial progenitor cells can contribute directly to angiogenesis in tumor formation.51-54 In addition, other studies have demonstrate that cancer-associated fibroblasts can be partly derived from BMDCs.55,56 Karnoub et al57 recently reported that bone marrow–derived human mesenchymal stem cells, when mixed with otherwise weakly metastatic human breast carcinoma cells, cause the cancer cells to increase their metastatic potency greatly, through stimulation of de novo secretion of the chemokine CCL5, when this cell mixture is introduced into a subcutaneous site and allowed to form a tumor xenograft. In view of the astonishing plasticity of BMDC, we speculated that BMDCs might contribute directly or indirectly to epithelial cancers, particularly those associated with chronic inflammation.

To to fully investigate this issue, animal models would seem to represent an excellent approach for studying cellular origins and lineage relationships. The model of gastric cancer in Helicobacter felis (H felis)-infected C57BL/6 mice represents an ideal system for evaluating the effects of chronic inflammation on BMDC recruitment and engraftment in the stomach. In this model, inflammation is maximal at around 2 to 3 months after infection, and then continues at a moderate level for the remainder of the life of the animal. With persistent Helicobacter infection, the gastric mucosa progresses through a series of dramatic changes, including metaplasia and dysplasia, and ends in GI intraepithelial neoplasia after 12 to 18 months of infection.58-60 The severity of intraepithelial dysplasia increases over time, and by 18 months of infection, most mice have developed invasive gastric cancer.

The BMDC is thought to be the most primitive uncommitted adult stem cell, and we theorized that it might represent the ideal candidate for transformation if recruited to a chronically inflamed tissue. Thus, we used lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice that were reconstituted with bone marrow cells labeled with a marker (eg, β-galactosidase or GFP) and the mice were subsequently infected with H felis. After 6 to 9 months of infection with H felis, mucosal atrophy, parietal cell loss, and mucus cell metaplasia appeared, and, notably, at the same time, the BMDC engraftment was first observed. As time goes by, the number of bone marrowν̵derived glands increases dramatically, suggesting that a threshold for recruitment may exist, and may be achieved at the 6-month time point.48 On the basis of these studies with the Helicobacter mouse model, it appears that chronic inflammation and tissue injury are associated with BMDC engraftment within the gastric epithelium, and this environment is also strongly linked with the progression of inflammation-associated cancer. As shown in Figure 2, all of the intraepithelial cancer cells in mice infected for 12 to 18 months originated from BMDCs. These data strongly indicate an innate susceptibility of BMDCs to neoplastic cell transformation.48 In addition, given the absence of normal gastric epithelial cells that are bone marrow derived, this suggests that, once engrafted in a stem-cell niche of inflammatory damaged tissues, the BMDCs are committed for abnormal differentiation and transformation.

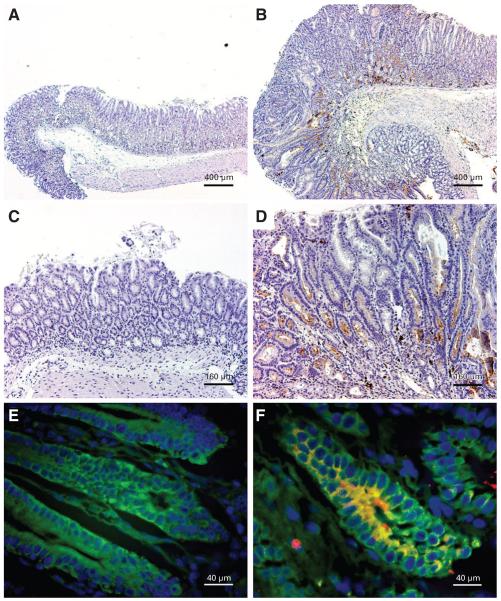

Fig 2.

(A-F) β-galactosidase immunohistochemistry of stomachs from Helicobacter felis (H felis )–infected C57BL/6 mice transplanted with ROSA26 marrow. (A and C) Mock-infected mice do not demonstrate any bone marrow–derived cell (BMDC) engraftment, as evidenced by lack of β-galactosidase staining. (B and D) H felis–infected mice have substantial architectural distortion and β-galactosidaseβpositive (brown) GI intraepithelial neoplasia (GIN). Fluorescence immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin (green) and β-galactosidase (red). (E) Glands within GIN from an infected mouse transplanted with wild-type marrow do not express β-galactosidase. (F) Glands within GIN from an infected mouse transplanted with ROSA26 marrow demonstrate β-galactosidase expression (red), colocalized with cytokeratin (green) to form yellow, confirming epithelial differentiation of integrated BMDC. Occasional mononuclear leukocytes are β-galactosidase positive (red) and cytokeratin negative. Scale bars, 400 μm (A and B), 160 μm (C and D), 40 μm (E and F). Adapted from Houghton et al49 with permission of the publisher.

BMDCs may also contribute to established cancers through cell mimicry or cell fusion, or may initiate cancer directly. Our previous studies did not support a role for cell fusion in this model, although recent data from other laboratories have suggested that cell fusion is a possible mechanism for bone marrow–derived hepatocytes and intestinal cells.61-65 Interestingly, recruitment of BMDCs to the gastric mucosa was not observed during acute gastric infection with Helicobacter species, nor was it observed during either acute ulceration or drug-induced parietal cell loss. Instead, as shown in Figure 2, BMDC-derived metaplasia arose only in the setting of severe, chronic inflammation. Currently, there is considerable interest in defining the association between chronic inflammation and recruitment of BMDCs. As shown in Figure 3, it would be expected to involve up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α, and chemokines such as CXCL12 (also known as SDF-1α) known to contribute to the recruitment of progenitors. Recent studies have pointed to activated myofibroblasts, alpha smooth muscle actin (a-SMA)–expressing stromal cells, that make up the stem-cell niche, as the probable source of CXCL12 that mediates progenitor recruitment.66,67

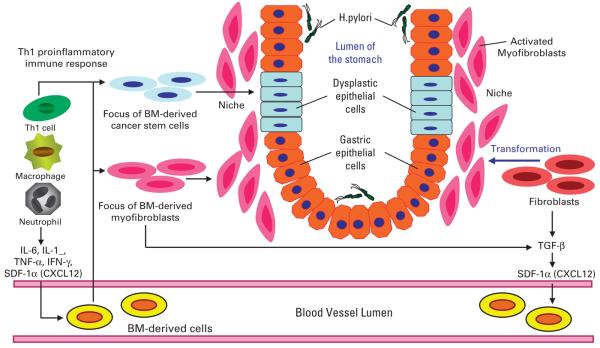

Fig 3.

Bone marrow (BM)–derived cells (BMDCs) in gastric tumor initiation and progression. Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic inflammation, driven by macrophages and Th1-polarized lymphocytes, results in increased cytokine and chemokine production that mobilizes and recruits BMDCs from the circulation. The proinflammatory milieu leads to an altered stem-cell niche, characterized by increased numbers of activated myofibroblasts, which can originate from both BMDCs and local stromal populations. Some of the BMDCs may also be recruited into the progenitor zone, giving rising to epithelial metaplasia and dysplasia (ie, cancer stem cells). Adapted from Fox and Wang20 with permission of the publisher. IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IFN, interferon; TGF, transforming growth factor; SDF, stromal cell–derived factor.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Recent studies have elucidated the presence of CSCs that have the exclusive ability of regenerating tumors as well as self-renewal and differentiation, and share many characteristics with tissue stem cells. Growing evidence firmly supports that CSCs exist in a wide array of solid tumors. Recent findings also support the existence of gastric CSCs in the human gastric tumors. The origin of human gastric CSCs has yet to be elucidated, but data obtained from a mouse model of Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer has implicated BMDCs as a potential candidate source. These findings will likely lead to new insights in inflammation-associated cancers of other organs.

Of note, two interesting therapeutic approaches have recently been reported in the experimental studies for treatment of brain CSCs.68 Bao et al69 reported that glioblastoma stem cells were generally resistant to radiation therapy, but that such radioresistance could be reversed with a specific inhibitor of Chk1 and Chk2 checkpoint kinases. Another approach reported by Piccirillo et al70 utilized BMP4, which can trigger a significant reduction in the stem-like, tumor-initiating precursors of human glioblastomas. In vivo delivery of BMP4 effectively blocks tumor growth and associated mortality that occur in 100% of mice after intracerebral grafting of human glioblastoma cells. These new therapies targeting brain CSCs may be applicable to CSCs derived from any other solid tumors including gastric cancer. Thus, the CSC hypothesis may facilitate the development of additional novel therapies for the treatment of human cancer.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants No. R01 CA120979 and R01 CA093405 (T.C.W) and in part by the Uehara Memorial Foundation (T.O.).

Footnotes

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Houghton J, Morozov A, Smirnova I, et al. Stem cells and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobo NA, Shimono Y, Qian D, et al. The biology of cancer stem cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:675–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang D, Nguyen TK, Leishear K, et al. A tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9328–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, et al. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–2556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prince ME, Sivanandan R, Kaczorowski A, et al. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:973–978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, et al. Cancer stem cells: Perspectives on current status and future directions—AACR Workshop on Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly PN, Dakic A, Adams JM, et al. Tumor growth need not be driven by rare cancer stem cells. Science. 2007;317:337. doi: 10.1126/science.1142596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marx J. Molecular biology. Cancer's perpetual source? Science. 2007;317:1029–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.317.5841.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houghton J, Wang TC. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: A new paradigm for inflammation-associated epithelial cancers. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1567–1578. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ushijima T, Sasako M. Focus on gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansson LR, Engstrand L, Nyren O, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in sub-types of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:885–888. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamangar F, Dawsey SM, Blaser MJ, et al. Opposing risks of gastric cardia and noncardia gastric adenocarcinomas associated with Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1445–1452. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus and gastric carcinoma. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:255–261. doi: 10.1136/mp.53.5.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peek RM, Jr, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blair V, Martin I, Shaw D, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: Diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Correa P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(suppl):S37–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Correa P, Houghton J. Carcinogenesis of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:659–672. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto Y, Marusawa H, Kinoshita K, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection triggers aberrant expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in gastric epithelium. Nat Med. 2007;13:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nm1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takaishi S, Wang TC. Providing AID to p53 mutagenesis. Nat Med. 2007;13:404–406. doi: 10.1038/nm0407-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–1183. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takaishi S, Okumura T, Tu S, et al. Isolation of gastric cancer-initiating cells using cell surface marker CD44. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A632. abstr. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vescovi AL, Galli R, Reynolds BA. Brain tumour stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:425–436. doi: 10.1038/nrc1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vargo-Gogola T, Rosen JM. Modelling breast cancer: One size does not fit all. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:659–672. doi: 10.1038/nrc2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, et al. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodell MA, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, et al. Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Nat Med. 1997;3:1337–1345. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okano H. Stem cell biology of the central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:698–707. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki A, Zheng Y, Kondo R, et al. Flow-cytometric separation and enrichment of hepatic progenitor cells in the developing mouse liver. Hepatology. 2000;32:1230–1239. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.20349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee ER. Dynamic histology of the antral epithelium in the mouse stomach: I, Architecture of antral units. Am J Anat. 1985;172:187–204. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001720303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee ER, Leblond CP. Dynamic histology of the antral epithelium in the mouse stomach: II, Ultra-structure and renewal of isthmal cells. Am J Anat. 1985;172:205–224. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001720304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee ER. Dynamic histology of the antral epithelium in the mouse stomach: III, Ultrastructure and renewal of pit cells. Am J Anat. 1985;172:225–240. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001720305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee ER, Leblond CP. Dynamic histology of the antral epithelium in the mouse stomach: IV, Ultra-structure and renewal of gland cells. Am J Anat. 1985;172:241–259. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001720306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bjerknes M, Cheng H. Multipotential stem cells in adult mouse gastric epithelium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G767–G777. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00415.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiao XT, Ziel JW, McKimpson W, et al. Prospective identification of a multi-lineage progenitor in murine stomach epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1989–1998. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houghton J, Stoicov C, Nomura S, et al. Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow-derived cells. Science. 2004;306:1568–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1099513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, et al. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okamoto R, Yajima T, Yamazaki M, et al. Damaged epithelia regenerated by bone marrow-derived cells in the human gastrointestinal tract. Nat Med. 2002;8:1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/nm755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avital I, Moreira AL, Klimstra DS, et al. Donor derived human bone marrow cells contribute to solid organ cancers developing after bone marrow transplantation. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2903–2909. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopp HG, Ramos CA, Rafii S. Contribution of endothelial progenitors and proangiogenic hematopoietic cells to vascularization of tumor and ischemic tissue. Curr Opin Hematol. 2006;13:175–181. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000219664.26528.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li B, Sharpe EE, Maupin AB, et al. VEGF and PlGF promote adult vasculogenesis by enhancing EPC recruitment and vessel formation at the site of tumor neovascularization. Faseb J. 2006;20:1495–1497. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5137fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spring H, Schuler T, Arnold B, et al. Chemokines direct endothelial progenitors into tumor neovessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18111–18116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507158102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, et al. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Direkze NC, Hodivala-Dilke K, Jeffery R, et al. Bone marrow contribution to tumor-associated myofibroblasts and fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8492–8495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang TC, Goldenring JR, Dangler C, et al. Mice lacking secretory phospholipase A2 show altered apoptosis and differentiation with Helicobacter felis infection. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:675–689. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, et al. Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: Consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:762–777. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai X, Carlson J, Stoicov C, et al. Helicobacter felis eradication restores normal architecture and inhibits gastric cancer progression in C57BL/6 mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1937–1952. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, et al. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;422:897–901. doi: 10.1038/nature01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR, Russell DW. Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature. 2003;422:901–904. doi: 10.1038/nature01539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Camargo FD, Finegold M, Goodell MA. Hematopoietic myelomonocytic cells are the major source of hepatocyte fusion partners. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1266–1270. doi: 10.1172/JCI21301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rizvi AZ, Swain JR, Davies PS, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells fuse with normal and transformed intestinal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6321–6325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508593103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li HC, Stoicov C, Rogers AB, et al. Stem cells and cancer: Evidence for bone marrow stem cells in epithelial cancers. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:363–371. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dirks PB. Cancer: Stem cells and brain tumours. Nature. 2006;444:687–688. doi: 10.1038/444687a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Piccirillo SG, Reynolds BA, Zanetti N, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;444:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature05349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]