Abstract

Background

Versus whites, blacks with diabetes have poorer control of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), higher systolic blood pressure (SBP), and higher low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol as well as higher rates of morbidity and microvascular complications.

Objective

To examine whether several mutable risk factors were more strongly associated with poor control of multiple intermediate outcomes among blacks with diabetes than among similar whites.

Design

Case-control study.

Subjects

A total of 764 blacks and whites with diabetes receiving care within 8 managed care health plans.

Measures

Cases were patients with poor control of at least two of three intermediate outcomes (HbA1c≥8.0%, SBP≥140 mmHg, LDL cholesterol≥130 mg/dl) and controls were patients with good control of all three (HbA1c<8.0%, SBP<140 mmHg, LDL cholesterol<130 mg/dl). In multivariate analyses, we determined whether each of five potentially mutable risk factors, including depression, low health literacy, poor adherence to medication, low self-efficacy for reducing cardiovascular risk, and poor patient-provider communication, predicted case or control status.

Results

Among blacks but not whites, in multivariate analyses depression (odds ratio [OR] 2.28, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.09-4.75) and having missed medication doses (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.01-3.81) were associated with greater odds of being a case rather than a control. None of the other risk factors were associated for either blacks or whites.

Conclusions

Depression and missing medication doses are more strongly associated with poor diabetes control among blacks than in whites. These two risk factors may represent important targets for patient-level interventions to address racial disparities in diabetes outcomes.

Keywords: Diabetes, Racial/Ethnic Groups, Health Outcomes

Compared with whites, blacks with diabetes have higher rates of several microvascular complications.1-4 While some earlier research identified racial disparities in the delivery of evidence-based processes of diabetes care such as dilated eye exams or screening for hypercholesterolemia,5,6 newer studies have found few differences between blacks and whites.7,8 And yet, substantial racial discrepancies remain as measured by such diabetes-related intermediate outcomes as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.7,9-11 Persistent racial disparities in intermediate outcomes likely contribute to continued disproportionate morbidity for blacks with diabetes.

Patients with diabetes must be able to self-manage their illness in order to prevent complications. Psychosocial and interpersonal obstacles to effective diabetes self-management increase the risk of poor metabolic control.12-14 Among blacks, depression,15 low health literacy,17 incomplete medication adherence,18,19 low self-efficacy for reducing cardiovascular risk,20 and poor patient-provider communication21 have all been associated with adverse health consequences. However, there is little data to evaluate which of these factors are most prevalent and/or most strongly associated with poor intermediate outcomes among blacks with diabetes.

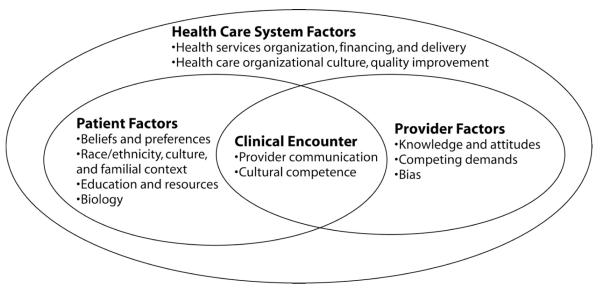

Within the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study, blacks have poorly controlled of HbA1c, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and LDL cholesterol compared to whites.7,11 Using data collected from a case control study of patients with diabetes, we examined the association of several mutable risk factors with control of these three intermediate outcomes. Because we were interested in issues that directly influence patient self-management, we examined patient-level risk factors rather than those at the level of the provider or health system (Figure). We hypothesized that each examined risk factor would be more strongly associated with poor control of these outcomes for blacks than for whites.

Figure.

Key potential determinants of health disparities within the health care system, including individual, provider, and health care system factors

34 Kilbourne AM, et al.

METHODS

TRIAD is a study of diabetes care in managed care, involving 10 health plans in 6 metropolitan areas across the United States.22 These health plans include for-profit, not-for-profit, Medicare, and Medicaid providers. The current analysis used data from a TRIAD questionnaire administered between March and September 2006 to “case” and “control” diabetic patients identified from diagnostic claims and/or the medical record within 8 of the plans. Cases were sampled from the population with recent poor control of at least 2 of the 3 intermediate outcomes (HbA1c ≥8.0%, SBP ≥140 mmHg, LDL cholesterol ≥130 mg/dl), and controls were sampled from the population with 1) established hypertension and hyperlipidemia from diagnostic claims or the medical record and 2) good control of all 3 outcomes (HbA1c <8.0%, SBP <140 mmHg, and LDL cholesterol <130 mg/dl). We used the most recent intermediate outcomes recorded in the 12 months prior to the survey to define case or control status.

Patients were excluded from the sampling frame if they had a gap in plan enrollment of >45 days during either the 12-month study window or the preceding 12 months. Enrollees were also excluded if they did not have all 3 intermediate outcomes (HbA1c, SBP, LDL cholesterol) measured within the study window, were unable to speak English or Spanish, or were ≤18 years of age.

TRIAD investigators attempted to contact 2609 persons to participate in the study. Of the 1615 persons who were successfully contacted, 1305 (80%) were eligible. Of these contacted, eligible persons, 1139 (87%) completed the survey. If persons who could not be contacted had the same rate of eligibility (80%) as those who were contacted, and if they were counted in the denominator, the survey response rate would be 54% (Council of American Survey Research Organizations [CASRO] response rate).23

All study variables were drawn from the participant surveys, with the exception of intermediate outcomes and body mass index obtained from medical record review. We included participants in the analytic sample if they identified their race as either “white” or “African American,” even if they indicated other racial backgrounds as well. Participants who indicated their race as African American were classified as black, even if they also reported a white racial background. We excluded participants (n=375) with 1) Latino ethnicity, 2) only nonwhite/nonblack race, or 3) missing data for race. We identified mutable risk factors as potential “exposures” that may be associated with poor control of intermediate outcomes, including incomplete medication adherence, perceived poor quality of provider communication, depression, low self-efficacy for reducing cardiovascular risk, and low health literacy.

We evaluated 2 measures of adherence to medication over the previous 6 months: running out of any medications or missing any medication doses (Appendix). Patients who indicated that they missed medication doses were asked follow-up questions to examine the underlying reasons. We modified 4 published scales to measure patients’ perceptions of the quality of provider communication (Appendix).24 Values for Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.59 to 0.81 for these modified scales. We defined depression as a score of ≥10 on the PHQ-8.25 We defined low self-efficacy for reducing cardiovascular risk as the acknowledgement that one was at high risk for heart disease, together with the belief that this risk could not be significantly lowered (Appendix). Finally, we created a summary score of 4 individual health literacy items.26 The responses for each original item ranged from 0 to 4, with higher values corresponding to lower health literacy. In constructing our score, we assigned a point for each item with a response greater than 0. We also examined demographic characteristics, including age, sex, education, income, and body mass index (BMI).

We investigated the unadjusted distributions of demographic characteristics by race and case or control status. Using SAS’s PROC GLIMMIX Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), we conducted separate unadjusted analyses and multivariate random effect models to examine associations between the presence of each risk factor and case or control status. In each unadjusted and adjusted model, we used interaction terms between risk factors and patient race to predict case and control status separately for black cases, black controls, white cases, and white controls. Each of the nine multivariate analyses controlled for fixed demographic characteristics, specifically age, sex, education, income, and study site. We used the 25th and 75th percentiles of the quality of provider communication scales to represent poor and good communication, respectively. Low health literacy was identified infrequently within our sample, and we were unable to fit a multivariate model for this variable.

Finally, we examined the unadjusted distributions of incomplete medication adherence among the subgroups of blacks and whites that missed medication doses. We considered results significant if P < 0.05. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, funded this study. Institutional review boards at all participating sites approved the study.

RESULTS

Our analytic sample included 764 respondents. Among the 557 whites, 34% (n=192) were classified as cases. Among the 205 blacks, 56% (n=115) were classified as cases. While the proportion of females was similar among white cases and controls, among blacks almost three-quarters of cases were female, compared with slightly more than 60% of controls (Table 1). Although whites reported higher levels of education and income, differences between cases and controls on these measures were similar for blacks and whites. Differences in the three intermediate outcomes between cases and controls were also similar for blacks and whites.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and risk factors of study patients, by race and case/control status

| White cases (n=192) |

White controls (n=367) |

Black cases (n=115) |

Black controls (n=90) |

P for unadjusted association between race and risk factor |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | |||||

| Mean age in years (SD) | 62.8 (11.8) | 64.1 (10.6) | 59.9 (10.8) | 63.8 (11.0) | |

| Female sex (%) | 54.2 | 51.5 | 73.0 | 60.7 | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school (%) | 18.4 | 13.4 | 27.0 | 25.6 | |

| High school graduate (%) | 28.4 | 25.7 | 35.7 | 33.3 | |

| Some college (%) | 53.2 | 60.9 | 37.4 | 41.1 | |

| Annual income ($) | |||||

| < 25,000 (%) | 32.9 | 26.8 | 57.5 | 47.2 | |

| 25,000-40,000 (%) | 18.1 | 13.7 | 8.5 | 11.1 | |

| 40,000-75,000 (%) | 24.2 | 31.7 | 21.3 | 23.6 | |

| 75,000-100,000 (%) | 12.8 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 6.9 | |

| > $100,000 (%) | 12.1 | 18.6 | 5.3 | 11.1 | |

| Mean body mass index (SD) | 33.3 (7.5) | 32.6 (8.3) | 35.0 (8.9) | 32.6 (7.0) | |

| Intermediate outcomes | |||||

| Mean hemoglobin A1c, % (SD) | 8.7 (1.5) | 6.6 (0.7) | 8.8 (1.8) | 6.6 (0.7) | |

| Mean systolic blood pressure, mmHg (SD) | 149.5 (19.3) | 125.6 (10.2) | 150.2 (18.7) | 124.0 (11.4) | |

| Mean LDL cholesterol, mg/dl (SD) | 131.3 (43.0) | 87.1 (20.8) | 138.7 (40.2) | 91.7 (24.2) | |

| Risk factor | |||||

| Depression (%) | 40.2 | 35.1 | 38.5 | 31.7 | 0.49 |

| Untreated depression (%) | 9.7 | 8.4 | 19.2 | 10.0 | 0.28 |

| Low self-efficacy for reducing cardiovascular risk (%) | 5.8 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 10.8 | 0.19 |

| Mean health literacy score* (+/-SD) | 0.31 (0.64) | 0.22 (0.54) | 0.39 (0.68) | 0.35 (0.69) | |

| Medication adherence | |||||

| Ran out of any medications (%) | 38.4 | 27.5 | 42.7 | 35.4 | 0.61 |

| Missed doses of any medications (%) | 72.2 | 68.6 | 73.5 | 52.3 | 0.04 |

| Provider communication skills | |||||

| Mean general clarity score# (SD) | 8.7 (1.6) | 8.6 (1.5) | 8.6 (1.5) | 8.5 (1.8) | 0.58 |

| Mean score of eliciting patient concerns@ (SD) | 12.9 (2.2) | 12.9 (2.3) | 12.8 (2.5) | 13.3 (2.4) | 0.007 |

| Mean score of discussing barriers to adherence# (SD) | 7.2 (2.6) | 7.4 (2.5) | 8.0 (2.5) | 7.7 (2.6) | 0.77 |

| Mean score of discussing patient preferences# (SD) | 6.7 (2.5) | 6.7 (2.6) | 6.7 (2.7) | 6.6 (2.7) | 0.76 |

Scores range from 0 to 4, with higher values indicating lower health literacy.

Scores range from 2 to 10, with higher values indicating better provider communication skills.

Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher values indicating better provider communication skills.

SD = standard deviation; LDL = low-density lipoprotein

In unadjusted models, a significant interaction was seen between race and both reports of missed medication doses (P=0.04) and scores for the patient concerns scale (P=0.007) as predictors of case or control status (Table 1). In multivariate analyses, no risk factors were associated with greater odds of case versus control status among white patients (Table 2). However, depression (odds ratio [OR] 2.28, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.09-4.75) and missed medication doses (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.01-3.81) were associated with greater odds of being a case rather than a control for black patients.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of good versus poor intermediate outcome control@ in the absence of selected risk factors, by race

| Blacks | Whites | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Odds of good versus poor control if risk factor not present OR, 95% CI |

Odds of good versus poor control if risk factor not present OR, 95% CI |

| Depression | 2.28 (1.09-4.75)* | 1.04 (0.63-1.72) |

| Untreated depression | 0.43 (0.17-1.11) | 0.68 (0.34-1.36) |

| Low self-efficacy for reducing cardiovascular risk | 0.60 (0.30-1.18) | 0.95 (0.59-1.54) |

| Medication adherence | ||

| Ran out of medications | 1.18 (0.61-2.30) | 1.29 (0.83-2.02) |

| Missed medication doses | 1.96 (1.01-3.81)* | 1.13 (0.72-1.78) |

| Provider communication skills# | ||

| Poor general clarity | 1.04 (0.73-1.47) | 1.09 (0.86-1.39) |

| Not eliciting patient concerns | 0.80 (0.56-1.15) | 1.05 (0.83-1.34) |

| Not discussing patient preferences | 1.11 (0.72-1.71) | 1.05 (0.78-1.40) |

| Not discussing barriers to medication adherence | 1.20 (0.77-1.87) | 0.94 (0.71-1.25) |

Results generated from nine separate models, each including an interaction term for race*risk factor

Adjusted for age, sex, education, income, and study site.

Patients with good intermediate outcomes met each of the following criteria: HbA1c<7.0%, SBP<130 mmHg, and LDL cholesterol<130 mg/dl.

P<0.05

Subscales of provider communication skills are continuous variables, and the results shown represent the odds of good control at the 25th percentile vs. the 75th percentile, within each racial group.

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

On average, in unadjusted analyses among respondents who reported missing medication doses, blacks gave 2.3 reasons for their incomplete adherence, versus 1.4 for whites (p=0.08). In addition, blacks were more likely than whites to endorse 10 of the 14 potential reasons for incomplete adherence, including issues related to lack of knowledge, complexity of the medication regimen, dislike of medications or side effects, clinical barriers, and forgetfulness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reasons for missing medication doses by race

| Blacks (n=128) |

Whites (n=354) |

Difference (Blacks- Whites) |

P value for difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number of reasons provided | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.01 |

| Lack of knowledge | ||||

| Doesn’t know what dose to take (%) | 6.2 | 2.3 | 3.9 | <0.001 |

| Not sure exactly what each medication is for (%) | 7.7 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 0.04 |

| Complexity of regimen | ||||

| Too hard to keep track of what to take and when (%) | 16.2 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 0.01 |

| Too many doses each day (%) | 20.0 | 8.6 | 11.4 | 0.002 |

| Lack of perceived benefits | ||||

| Doesn’t feel medications are helping (%) | 12.5 | 8.0 | 4.5 | 0.08 |

| Taking medications means health will get worse (%) | 7.1 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 0.08 |

| Dislike of medications/side effects/medication-related symptoms | ||||

| Doesn’t like taking medications in general (%) | 18.5 | 10.4 | 8.1 | 0.04 |

| Experienced side effects (%) | 22.8 | 13.4 | 9.4 | 0.004 |

| Heard about potential side effects (%) | 17.7 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 0.002 |

| Unpleasant to take (%) | 8.5 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 0.10 |

| Clinical barriers | ||||

| Doesn’t have time to ask doctor or nurse about problems (%) | 8.4 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 0.03 |

| Hard to ask doctor or nurse about medication-related problems (%) | 10.7 | 3.4 | 7.3 | 0.001 |

| Forgetfulness | ||||

| Forgets to take medications (%) | 48.5 | 40.1 | 8.4 | 0.47 |

| Forgets to ask about medication-related problems (%) | 14.5 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 0.04 |

Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) shown in bold

DISCUSSION

In this study of diabetes patients within managed care organizations, depression and missing doses of medication were more strongly associated with poor control of intermediate outcomes among blacks than among whites. We did not find evidence to support hypotheses that running out of medications, low self-efficacy for reducing cardiovascular risk, or poor provider communication skills was disproportionately associated with inadequate control for blacks. Depression and missing doses of medications are both potentially modifiable. Interventions targeting these factors may mitigate health disparities in diabetes outcomes.

Major depression, which is common among diabetes patients, is associated with poor control of intermediate outcomes.27,28 While screening tools such as the PHQ are equally valid in identifying depression among blacks and whites,29 the stronger link between depression and poor control for blacks may be related to different depression-related experiences in black and white patients. For example, blacks with diabetes and depression are more likely to report racial discrimination and subsequent high levels of stress than are blacks with diabetes alone.30 An interaction between depression and perceived discrimination could influence adherence to diabetes medication and recommendations for self-care, particularly if such recommendations are perceived to originate from an antagonistic health system.

Existing interventions that have successfully treated depression in populations with diabetes have generally not demonstrated improvements in HbA1c31,32 However, these studies included few black patients. If the social context of depression differs for blacks and whites, it is not surprising that the relationship between depression and control of intermediate outcomes also differs by race. Developing effective, culturally tailored approaches to identify and treat depression among black patients may represent a key step toward eliminating racial disparities in diabetes-related intermediate outcomes.

Our finding of an association between any missed medication doses and poor control of intermediate outcomes among blacks but not whites seems to have been due to low reported rates of nonadherence among black controls. Perhaps black controls overestimated their adherence to provide socially desirable responses, but there is no evidence in the literature that this type of bias is greater among blacks than other groups.33 Alternatively, exceptional adherence to medications among a subset of black patients may explain their good control of intermediate outcomes, and may potentially explain how these “resilient” persons are able to overcome the presence of adverse risk factors such as low socioeconomic status. Enhancing medication adherence to shift black patients from “poor control” to “good control” could represent another critically important strategy in the effort to eliminate disparities in diabetes outcomes. Notably, our findings that black patients were more likely than white patients to report each of ten different reasons for missing medication doses suggests that interventions targeted at black patients will need to simultaneously address multiple obstacles to adherence.

Our study had several limitations. We may have lacked power to detect associations between certain risk factors, race, and case or control status. Due to the case-control design, we cannot generalize these results to populations of blacks and whites with diabetes, and the negative results we found for several risk factors do not imply that these factors are not associated with poor outcomes in other populations. Instead, our study was intended to identify the foremost risk factors for black-white disparities among patients with poor control of multiple intermediate outcomes and to guide the development of future interventions designed to mitigate health disparities in diabetes outcomes. Finally, because our study was not longitudinal, we cannot establish a causal link between the identified risk factors and poor control of intermediate outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that depression and missing medication doses were more strongly associated within this managed care sample with simultaneous poor control of blood pressure, blood glucose, and cholesterol among blacks than among whites. While the importance of these two modifiable risk factors should be confirmed in population-based samples, they may represent attractive targets for patient-level interventions to address black-white disparities in intermediate and long-term outcomes among patients with diabetes.

Appendix

Selected questionnaire items used to define predictor variables/risk factors

| Low Health Literacy Scale26 Each original item was scored from 0-4, with higher scores indicating lower health literacy. We created a scale assigning 1 point for each response greater than 0. |

||

| How often do you have someone like a family member, friend, hospital or clinic worker or caregiver, help you read health-related materials? |

||

| How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information? |

||

| How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself? | ||

| In the last 12 months, how often did doctors or other health care providers explain things in a way you could understand? |

||

| Low Self-efficacy for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction (defined as a response of “high” or “very high” to item #1 but a response of “not at all” or “a little” to item #2) |

||

| Item #1: Acknowledgement of risk: “What do you think your risk is of having a heart attack in the next 10 years?” |

||

| Item #2: Belief of ability to lower risk: “How much do you think that you or your doctor can lower your risk or chance of a heart attack?” |

||

| Ran Out of Medication (1 item) | ||

| In the past 6 months, did you ever run out of any medicines that were prescribed by your doctor or another health provider? |

||

| Missed Medication Doses (1 item) | ||

| In the past 6 months, did you ever miss a dose of any of your medicines, even just one pill or shot? |

||

| Provider Communication Scales24 Each original item was scored from 1-5, with higher scores indicating better provider communication as perceived by respondents. We created a summary scale with scores ranging from 2-10 (except eliciting patient concerns which ranges from 3-15). |

Cronbach’s α | |

| General Clarity (2 items, reverse coded) |

How often did doctors speak too fast? | 0.59 |

| How often did doctors use words that were hard to understand? | ||

| Eliciting Patient Concerns (3 items) |

How often did doctors find out what your concerns really were? | 0.73 |

| How often did doctors let you say what you thought was important? | ||

| How often did doctors take your health concerns very seriously? | ||

| Discussing Patient Preferences (2 items) |

How often did you and your doctors work out a treatment plan together? |

0.76 |

| If there were treatment choices, how often did doctors ask if you would like to help decide your treatment? | ||

| Discussing Barriers to Medication Adherence (2 items) |

How often did doctors ask if you would have any problems following what they recommended? |

0.81 |

| How often did doctors ask you if you felt you could do the recommended treatment? | ||

REFERENCES

- 1.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002;287:2519–2527. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonds DE, Zaccaro DJ, Karter AJ, Selby JV, Saad M, Goff DC., Jr. Ethnic and racial differences in diabetes care: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1040–1046. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heisler M, Smith DM, Hayward RA, Krein SL, Kerr EA. Racial disparities in diabetes care processes, outcomes, and treatment intensity. Med Care. 2003;4:1221–1232. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093421.64618.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gary TL, McCauley J McGuire, Brancati FL. Racial comparisons of health care and glycemic control for African American and white diabetic adults in an urban managed care organization. Dis Manag. 2004;7:25–34. doi: 10.1089/109350704322918970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris MI. Racial and ethnic differences in health care access and health outcomes for adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:454–459. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM. Racial disparities in the quality of care for enrollees in medicare managed care. JAMA. 2002;287:1288–1294. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown AF, Gregg EW, Stevens MR, et al. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and quality of care for adults with diabetes enrolled in managed care: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2864–2870. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare managed care. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:692–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Relationship between quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare health plans. JAMA. 2006;296:1998–2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirk JK, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Bell RA, et al. Disparities in HbA1c levels between African-American and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2130–2136. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selby JV, Swain BE, Gerzoff RB, et al. Understanding the gap between good processes of diabetes care and poor intermediate outcomes: Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Med Care. 2007;45:1144–1153. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181468e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40:794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher L, Glasgow RE. A call for more effectively integrating behavioral and social science principles into comprehensive diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2746–2749. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gary TL, Crum RM, Cooper-Patrick L, Ford D, Brancati FL. Depressive symptoms and metabolic control in African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:23–29. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvan FH, Caetano R. Alcohol use and related problems among ethnic minorities in the United States. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sentell TL, Halpin HA. Importance of adult literacy in understanding health disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:862–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the health and retirement study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1853–1860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosworth HB, Dudley T, Olsen MK, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. Am J Med. 2006;119:70.e9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smedley BD, Syme SL. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1713–1719. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.TRIAD Study Group The Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study: a multicenter study of diabetes in managed care. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:386–389. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Council of American Survey Research Organizations . Special Report: On the definition of response rates. CASRO; Port Jefferson, NY: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart AL, Nápoles-Springer A, Pérez-Stable EJ. Interpersonal Processes of Care in Diverse Populations. The Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77:305–339. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36:588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner J, Abbott G. Depression and depression care in diabetes: relationship to perceived discrimination in African Americans. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:364–366. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams JW, Jr, Katon W, Lin EH, et al. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:1015–1024. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, editors. Patient Treatment Adherence: Concepts, Interventions, and Measurement. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113–2121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]