Abstract

Statement of translational relevance

Despite significant efforts over the last two decades aimed at improving the efficacy of standard treatment (maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of dacarbazine), there has been no significant increase in the median survival of patients suffering from metastatic melanoma. Given the lack of success achieved, a rethinking of alternative treatment strategies is needed. Using preclinical models of advanced melanoma metastasis, we show that metronomic chemotherapeutic combinations results in improved survival, which is achieved with minimal toxicity. These results compare favorably with minimal effectiveness achieved by MTD dacarbazine therapy (alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents or a VEGFR-blocking antibody), often accompanied by higher toxicity. Successes in preclinical setting of metastatic breast cancer have led to a clinical trial to examine the efficacy of metronomic therapy. A similar extension of the metronomic chemotherapeutic combinations presented here into the clinical setting of melanoma metastasis may be warranted.

Purpose

The development of effective therapeutic approaches for treatment of metastatic melanoma remains an immense challenge. Present therapies offer minimal benefit. While dacarbazine (DTIC) chemotherapy remains the standard therapy, it mediates only low response rates, usually of short duration, even when combined with other chemotherapeutic agents. Thus, new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed.

Experimental design

Using a newly developed preclinical model, we evaluated the efficacy of various doublet metronomic combination chemotherapy against established, advanced melanoma metastasis and compared these to the standard maximum tolerated dose (MTD) DTIC (alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic agents or VEGFR-blocking antibody)

Results

Whereas MTD DTIC therapy did not cause significant improvement in median survival, a doublet combination of low-dose metronomic (LDM) vinblastine (Vbl) and LDM cyclophosphamide (CTX) induced a significant increase in survival with only minimal toxicity. Furthermore, we show that the incorporation of the LDM Vbl/LDM CTX combination with a LDM DTIC regimen also results in a significant increase in survival, but not when combined with MTD DTIC therapy. We also show that a combination of metronomic Vbl therapy and a VEGFR2-blocking antibody (DC101) results in significant control of metastatic disease and that the combination of LDM Vbl/DC101 and LDM DTIC induced a significant improvement in median survival.

Conclusions

The effective control of advanced metastatic melanoma achieved by these metronomic-based chemotherapeutic approaches warrants clinical consideration of this treatment concept given the recent results of a number of metronomic-based chemotherapy clinical trials.

Keywords: melanoma, spontaneous metastasis, vinblastine, cyclophosphamide, DC101, metronomic chemotherapy

Introduction

Metastatic melanoma is generally associated with poor prognosis. The aggressiveness of the disease is compounded by the lack of effective treatment, with only modest progress being made over the last few decades in the discovery of chemotherapeutic drugs or other therapies showing a meaningful clinical survival benefit in randomized clinical trials. While single-agent chemotherapy with dacarbazine (DTIC) has long been the standard systemic treatment for metastatic melanoma, it is associated with low response rates of short duration (1, 2). Various combinations of chemotherapeutic agents, some of which have included DTIC, have also shown only very modest effects on increasing response rates and with little or no effect on improving median survival times (3–6). All of these approaches have involved conventional maximal tolerated dose (MTD) regimens in which prolonged breaks are used between treatments to allow recovery from induced toxic side effects. Significant efforts have been made to enhance the efficacy of DTIC therapy by using it in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. In the face of the disappointing results achieved thus far with such MTD approaches, it is obvious that new drugs and/or treatment strategies are needed. In this regard, the effectiveness of metronomic chemotherapy, in which drugs are given in low, minimally toxic doses at frequent regular intervals with no prolonged breaks, usually over long periods of time (7, 8), has been assessed in only a few situations in patients with metastatic or primary melanoma, thus far (9–12). Metronomic chemotherapy regimens have several potential advantages including reduced acute toxic side effects, convenience when using oral drugs, and activity in some cases against refractory drug-resistant tumors; in addition they are easily combined for prolonged periods with targeted biologic therapies such as anti-angiogenic drugs, with such combinations sometimes causing surprisingly robust and prolonged tumor responses (7, 8, 13–15).

Evaluation of metronomic chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced metastatic disease was initially performed in a model employing breast cancer xenografts (13). The underlying rationale was that such models might have superior predictive value for showing a clinical benefit in patients having the respective cancer with advanced metastatic disease. Our breast cancer results showed that a highly effective treatment could be achieved with the doublet combination of concurrent low-dose metronomic (LDM) oral cyclophosphamide (CTX) and UFT, a 5-FU oral pro-drug (13). More recent work from our lab using the 113/6-4L preclinical model of advanced melanoma metastasis, where visceral metastases in sites such as the liver, lung and lymph nodes arise from orthotopically transplanted and then surgically resected tumors, has also shown that the use of low-dose metronomicchemotherapy using the combination of LDM vinblastine (Vbl; administered intraperitoneally three times per week) and LDM oral CTX results in a beneficial survival effect with minimal toxicity (16). Here we expand on this initial preclinical therapy trial and examined how this doublet metronomic chemotherapy regimen compares with a standard MTD DTIC therapeutic regimen, as well as whether the efficacy of MTD DTIC can be enhanced by its combination with metronomic Vbl/CTX. DTIC treatment is associated with the transcriptional upregulation of genes encoding tumor growth promoting factors such as VEGF in melanoma cells (17). This upregulation may potentiate mechanisms leading to increased angiogenesis, and enhanced tumor growth, as well as metastasis. As such, therapeutic inhibition of VEGF inhibition might be an important option to consider when designing effective DTIC-based approaches for treating melanoma metastasis. Previous results from our lab indicate that treatment with a metronomic combination of LDM Vbl and optimal biological doses of a VEGFR2-inhibiting antibody (DC101) results in sustained regression of established subcutaneous tumor (neuroblastoma) without inducing overt toxicity (18). Thus we also examined whether the addition of the antiangiogenic drug DC101 can enhance the effectiveness of DTIC-based therapies for the treatment of advanced metastatic melanoma.

Materials and methods

Preclinical models of spontaneous melanoma metastasis

The 113/6-4L model of spontaneous melanoma metastasis has been previously described. The line was derived from the WM239 human melanoma cell line by serial selection of lung metastases arising in mice after orthotopic implantation of WM239 cells followed by surgical resection of the primary tumor (16). Briefly, one million 113/6-4L melanoma cells were injected subdermally into CB-17 SCID female mice and primary tumors were allowed to develop to a size of 400–500 mm3, at which time they were resected. Mice in the control and treatment groups were monitored regularly in accordance with the institutional guidelines stipulated by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Animal Care Committee and sacrificed when they showed signs of stress (e.g. breathing difficulty and severe weight loss). A similar approach was taken in the case of the MDA-MB-435 model of spontaneous metastasis. This cell line was initially isolated and studied as a breast cancer model, but has now been recognized as representative of a human melanoma based on genomic and protein profiling (19–23). Extensive visceral metastases were observed in these models, within one month of removal of the primary tumor.

Impact of metronomic, MTD and combination chemotherapy on survival

In the 113/6-4L model, chemotherapy was initiated 56 days after primary tumor resection, at which time extensive visceral metastatic tumor burden was present, especially evident in lungs and liver (16). Mice were treated for long periods, between 100 to 133 days in the various experiments performed. The study consisted of three experiments: experiment #1 examined the efficacy of LDM Vbl/LDM CTX vs. MTD DTIC; experiment #2 examined the efficacy of MTD DTIC and LDM DTIC as well as whether the addition of LDM Vbl or LDM Vbl/LDM CTX could improve the efficacy of these DTIC-based regimens; whereas experiment #3 examined whether the incorporation of the LDM Vbl+DC101 combination could enhance the efficacy of MTD or LDM DTIC regimens. Descriptions of all treatment regimens (including doses, routes of delivery and number of mice) are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of regimens examined using the 113/6-4L model of advanced metastatic disease

| Experiment #1 | Treatment | Number of mice |

|---|---|---|

| saline | normal saline daily in drinking water and ip 3x weekly | 17 |

| LDM Vbl+LDM CTX | Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly; 20 mg/Kg CTX po | 14 |

| MTD DTIC | DTIC 50 mg/kg ip in days 1–5 of a 21 day cycle | 17 |

|

| ||

| Experiment #2 | Treatment | Number of mice |

|

| ||

| Saline | normal saline daily in drinking water and ip 3x weekly | 9 |

| MTD DTIC | DTIC 50 mg/kg ip in days 1–5 of a 21 day cycle | 9 |

| MTD DTIC+LDM Vbl | DTIC 50 mg/kg ip in days 1–5 of a 21 day cycle | 11 |

| Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly | ||

| MTD DTIC+LDM Vbl+LDM CTX | DTIC 50 mg/kg ip in days 1-5 of a 21 day cycle | 6 |

| Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly; 20 mg/Kg CTX po | ||

| LDM DTIC | DTIC 5mg/Kg ip 3x weekly | 9 |

| LDM DTIC+LDM Vbl | DTIC 5mg/Kg ip 3x weekly | 11 |

| Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly | ||

| LDM DTIC+LDM Vbl+LDM CTX | DTIC 5mg/Kg ip 3x weekly | 11 |

| Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly; 20 mg/Kg CTX po | ||

|

| ||

| Experiment #3 | Treatment | Number of mice |

|

| ||

| saline | normal saline daily in drinking water and ip 3x weekly | 8 |

| LDM Vbl+DC101 | Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly; DC101 800 mg/kg ip 2x weekly | 7 |

| LDM Vbl+LDM CTX+DC101 | Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly; 20 mg/Kg CTX po | 8 |

| DC101 800 mg/kg ip 2x weekly | ||

| MTD DTIC+LDM Vbl+DC101 | DTIC 50 mg/kg ip in days 1-5 of a 21 day cycle | 8 |

| Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly; DC101 800 mg/kg ip 2x weekly | ||

| LDM DTIC+LDM Vbl+DC101 | DTIC 5mg/Kg ip 3x weekly; Vbl 0.33 mk/Kg ip 3x weekly | 7 |

| DC101 800 mg/kg ip 2x weekly | ||

Vbl/CTX and Vbl/DC101 combinations were examined alone or in combination with MTD DTIC and LDM DTIC;

MTD DTIC=maximum tolerated dose DTIC, LDM DTC= low dose metronomic DTIC

In the case of the MDA-MB-435 metastasis model, treatment was initiated 8 days post-primary tumor removal and continued for 84 days. Mice were assigned to specific treatment groups: group 1: control (Nornal saline (NS) intraperitoneally (ip) 3x weekly; n=11), group 2: LDM Vbl (0.33 mg/Kg, ip3x weekly) plus DC101 (800 mg/Kg, ip 2x weekly); (n=10), group 3: DC101 (800 mg/Kg, ip 2x weekly; n=10).

The efficacy of these regimens on primary tumor growth was also examined. In this case, 1×106 cells were implanted subdermally and primary tumors allowed to develop. Once tumors reached an average size of 200 mm3, treatment was initiated and given in the regimens described above for control, LDM Vbl+DC101 and DC101. Additional treatment regimens included LDM CTX (20 mg/Kg po)+NS, LDM Vbl (0.33 mk/kg, ip 3x weekly)+NS and LDM CTX (20 mg/Kg po)+ DC101 (800 mg/Kg, ip 2x weekly). For this experiment, 5 mice per group were used. Mice were monitored regularly and the experiment was terminated when tumors reached an average size of 1500 mm3.

Statistical significance difference in survival outcomes between control and each treatment group was performed using logrank test (P<0.05 indicated statistical significance). Hazard ratio was equally performed by comparing control vs. each treatment group. Statistical analysis was performed with the aid of GraphPad Prism4 software.

Results

MTD DTIC chemotherapy does not improve survival of mice with advanced metastatic melanoma

Using the 113/6-4L model, we examined the efficacy of standard MTD DTIC therapy and compared the results to those achieved by observation-alone. Our results show that MTD DTIC therapy is associated with minimal increases in median survival, which are not significantly different form control and associated with a high hazard ratio (p=0.42, hazard ratio=0.71; Figure 1a and Table 2). This result is similar to those obtained in meta-analysis of patient outcomes comparing median survival of untreated and DTIC monotherapy patients (24) and highlights both the poor efficacy of this standard therapy, as well as the importance of developing alternative and more effective therapies.

Figure 1. Efficacy of standard MTD DTIC in combination with metronomic Vbl/CTX in the 113/6-4L model of advanced metastatic melanoma.

A) Examination of the efficacy of standard MTD DTIC and Vbl/CTX metronomic chemotherapeutic regimens against advanced melanoma metastatic disease. B) Examination of body weights of mice treated with standard MTD DTIC, Vbl/CTX and saline (control). Error bars represent +/− SEM.

Table 2.

Summary of median survival times

| Median survival (days) | p (vs saline) | Hazard ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 156 | ||

| MTD DTIC | 172 | 0.420 | 0.71 |

| LDM Vbl+LDM CTX | undefined | 0.026 | 0.29 |

|

| |||

| Median survival (days) | p (vs saline) | Hazard ratio | |

|

| |||

| Control | 110 | ||

| MTD DTIC | 147 | 0.120 | 0.47 |

| MTD DTIC+LDM Vbl | 178 | 0.063 | 0.37 |

| MTD DTIC+DLM Vbl+LDM CTX | 168 | 0.063 | 0.35 |

| LDM DTIC | 154 | 0.115 | 0.47 |

| LDM DTIC+LDM Vbl | 192 | 0.026 | 0.35 |

| LDM DTIC+LDM Vbl+LDM CTX | 195.5 | 0.024 | 0.33 |

|

| |||

| Median survival (days) | p (vs control) | Hazard ratio | |

|

| |||

| Control | 156 | ||

| MTD DTIC | 191 | 0.66 | 0.76 |

| MTD DTIC+LDM Vbl+DC101 | 189 | 0.33 | 0.59 |

| LDM DTIC+LDM Vbl+DC101 | undefined | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| LDM Vbl+DC101 | undefined | 0.11 | 0.3 |

| LDM Vbl+LDM CTX+DC101 | 183 | 0.30 | 0.49 |

Metronomic combinations showed improved survival compared to contol. None of the therapies that incorporated MTD DTIC resulted in significant increase in survival. MTD=maximum tolerated dose, LDM=low dose metronomic.

Superior survival achieved by Vbl/CTX combination metronomic therapy

Preliminary examination of effectiveness of metronomic combination of LDM Vbl/LDM CTX suggested that this therapy can also induce an increase in median survival times in our preclinical model of advanced melanoma metastasis (16). Further assessment of the efficacy of this combination showed that it mediates a significant increase in median survival when compared to control (saline-alone) with an improved hazard ratio (p=0.026, hazard ratio=0.29; Figure 1a and Table 2). Importantly, long-term treatment with the LDM Vbl/LDM CTX combination was associated with minimal toxicity in metastasis bearing mice, as denoted by a stable body weight in the treatment group (Figure 1b). Mice in MTD DTIC groups maintained stable body weight but showed signs of distress (scruffiness and lethargy), which became more evident after each additional cycle of treatment. No such signs of distress were noted in the LDM Vbl/LDM CTX treatment group. Both survival and hazard ratio mediated by this metronomic chemotherapy regimen were superior to values achieved by MTD DTIC therapy alone.

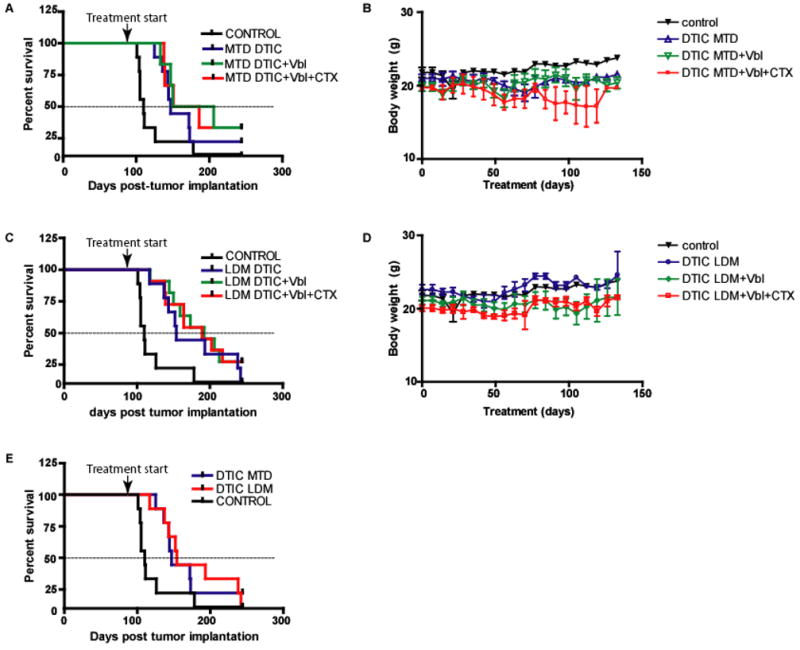

Given the efficacy of LDM Vbl/LDM CTX combination therapy, we next examined whether addition of this combination to standard MTD DTIC or LDM DTIC therapy could improve survival. In the case of MTD treatment, the addition of LDM Vbl alone or LDM Vbl/LDM CTX combination resulted in an increase in median survival from 147 days for MTD DTIC to 178 and 168 days respectively. However this increase did not reach statistical significance when compared to control (p=0.063, Figure 2a, Table 2). Mice in these groups, especially the MTD DTIC/LDM Vbl/LDM CTX group, showed signs of toxicity associated with weight loss (Figure 2b). This toxicity highlights one of the limitations associated with MTD regimens, especially when it is used in polychemotherapeutic combinations. On the other hand, the addition of LDM Vbl alone or LDM Vbl/LDM CTX to LDM DTIC resulted in significant increase in survival relative to control (Figure 2c, Table 2) and moreover, was associated with minimal toxicity (Figure 2d). Interestingly, LDM DTIC therapy was just as effective as the standard MTD DTIC regimen; however the former had the added advantage of lower toxicity (Figure 2e).

Figure 2. Vbl and Vbl/CTX enhance survival when combined with LDM DTIC therapy in the 113/6-4L preclinical model of advanced metastatic melanoma.

A) Survival curves associated with MTD DTIC as well as those in which this standard treatment was combined with Vbl and Vbl/CTX in the preclinical treatment of advanced met. B) Body weights during the course of treatment with various regimens incorporating MTD DITC. C) Survival curves associated with LDM DTIC as well as those in which this treatment was combined with Vbl and Vbl/CTX. D) Body weights during the course of treatment with various chemotherapeutic combinations incorporating LDM DTIC. E) Survival curves associated with LDM DTIC and MTD DTIC regimens. Error bars represent +/−SEM.

The combination of LDM Vbl/DC101 results in improved survival in the MDA-MB-435 model of spontaneous metastasis

We had previously shown in the MDA-MB-435 melanoma model of advanced metastatic disease that DC101 alone exerts minimal effect on survival whereas metronomic Vbl alone could significantly prolong survival (25). Here our results show that the combination of LDM Vbl and DC101 resulted in a dramatic suppression of metastatic disease and resulted in a significant increase in survival (p<0.0001, hazard ratio=0.04; Figure 3a). In addition, this combination was found to be associated with significant inhibition of primary tumor growth (Figure 3b). No such inhibition was noted by treatment with DC101 alone or in the case of, LDM Vbl+NS or LDM CTX+NS LDM CTX+DC101. The last two regimens had also shown no significant effect on survival when used in the treatment of advanced metastatic disease (25).

Figure 3. Vbl/DC101 therapy suppresses metastatic disease and primary tumor growth in the MDA-MB-435 model of advanced metastatic disease.

A) Survival curves associated with Vbl/DC101 and DC101 metronomic regimens in the treatment of advanced metastatic disease. B) Examination of efficacy of Vbl/DC101 and DC101 against growth of primary MDA-MB-435 tumors. Error bars represent +/− SEM.

The incorporation of metronomic Vbl+DC101 to LDM DTIC results in effective control of metastatic melanoma

We examined whether incorporation of the doublet LDM Vbl+DC101 combination could enhance the efficacy of MTD or LDM DTIC chemotherapy. At the same time, we examined whether combination of LDM Vbl+DC101 with LDM CTX could result in increased anti-tumor effectiveness and survival. Using the 113/6-4L model, we found that LDM Vbl+DC101 did result in an improved outcome compared to control mice significance (p=0.08, hazard ratio 0.2, Figure 4a, Table 2). The beneficial effect of the LDM Vbl+DC101 therapy did not reach statistical significance as a number of mice succumbed to toxicity mediated by long-term DC101 treatment (characterized by loss of weight, Figure 4b). In these mice, no metastases were observed in either the chest cavity or in the CNS. The addition of CTX or MTD DTIC to the LDM Vbl+DC101 combination did not result in enhanced survival but was associated with an exacerbation in toxicity (Figure 4a, 4b, 4c and 4d; Table 2). Interestingly, a high proportion of mice (3/4) that succumbed to metastatic disease in the MTD DTIC/LDM Vbl/DC101 group showed extensive signs of CNS melanoma metastases; such a high frequency of CNS metastasis was not observed in any other treatment group. Contrary to the lack of additional activity achieved by MTD based therapies; the addition of LDM Vbl+DC101 to LDM DTIC resulted in a dramatic suppression of metastatic disease and improved median survival (p=0.01, hazard ratio=0.11; Figure 4e; Table 2). This triplet combination also showed minimal toxicity in the treated mice (Figure 4f) even after 13 weeks of continuous treatment.

Figure 4. Examination of the effect of Vbl/DC101 in the 113/6-4L model of spontaneous melanoma metastasis.

A) Survival curves associated with Vbl/DC101 and Vbl/DC101/CTX regimens in the treatment of advanced metastatic disease in the 113/6-4L model. B) Body weights during the course of treatment with Vbl/DC101 or Vbl/DC101/CTX. C) Survival curves associated with MTD DTIC or MTD DTIC+Vbl+DC101 regimens in the treatment of metastatic disease. D) Body weights during treatment with MTD DTIC or MTD DTIC/Vbl/DC101 regimens. E) Survival curves associated with metronomic regimen incorporating LDM DTIC+Vbl+DC101 in the treatment of advanced melanoma metastasis. F) Body weights during the course of treatment with LDM DTIC+Vbl+DC101 therapy. Error bars represent +/− SEM.

Discussion

DTIC has minimal impact on survival of melanoma patients. Indeed, its effectiveness has not been compared directly to observation-alone, and as such there is no clear indication as to whether it improves survival (24). Given its limited therapeutic activity, DTIC has been combined with a number of other chemotherapeutic drugs in an effort to improve efficacy; indeed a large number of clinical trials remain underway evaluating such combinations (http://clinicaltrials.gov). The testing of these combinations has not been generally evaluated pre-clinically using primary tumor models, let alone those involving advanced metastatic disease. However, taking such empiric approaches into the clinic may lead to the unnecessary and premature exposure of patients to drugs for which adequate proof of activity has not been shown and for which possible toxicities have not been fully evaluated (26). Thus, preclinical evaluation of anti-metastatic activity could be an essential step in the development of more effective therapeutic approaches for malignant melanoma. However, in order to increase relevance, such evaluation should be conducted in models that reflect the typical presentation of metastatic disease frequently seen in patients involved in clinical trials, namely, advanced, high volume metastatic disease (25, 27). In this regard, we have observed several instances where the outcomes of anti-tumor activity using primary xenograft tumor models did not correlate with anti-metastatic activity (13, 16). Such a disconnect may be an important factor in the frequent disparity observed between promising preclinical therapeutic results using such primary tumor models and the subsequent, usually less impressive results observed in clinical trials.

Because they more closely reflect the clinical presentation of disease, preclinical models of advanced metastatic disease likely represent a more useful tool to examine therapies to be used for the treatment of late-stage metastases (25, 28). In support of this argument, attention is drawn to the results of a recently reported non-randomized phase II clinical trial in metastatic breast cancer patients employing a doublet metronomic chemotherapy combination, namely daily CTX and capecitabine, an oral 5-FU pro-drug, used in combination with bevacizumab, a monoclonal anti-VEGF antibody (29). This trial was undertaken, in part, based on our prior preclinical results showing the potent activity of long-term daily low-dose CTX with daily low-dose UFT (another 5-FU oral pro-drug) that was used to treat established, advanced visceral metastatic human breast cancer using a single newly developed preclinical model of advanced spontaneous metastasis (13).

The 113/6-4L model of spontaneous melanoma metastasis used in the studies described herein, recapitulates all the events and steps involved in the multistep process of metastasis seen in clinic, including brain metastases (16). Using this model, we have demonstrated that metronomic chemotherapy combination regimens are effective in controlling one of the most intractable of metastatic diseases, late stage melanoma metastasis, and moreover, do so with surprisingly little associated toxicity. Furthermore, our results show that the standard MTD DTIC therapy for treatment is not as effective and other results suggest that even when combined with other agents (either chemotherapeutics or anti-angiogenics), DTIC therapy provides minimal improvement in survival.

The results we have obtained should be considered in the context of the numerous clinical trials that are underway examining polychemotherapeutic approaches based on the use of MTD DTIC. The anti-tumor effects achieved by the LDM Vbl/LDM CTX or LDM DTIC/LDM Vbl/DC101 treatments suggest that improved survival in melanoma patients might be achieved by such combination metronomic therapy approaches, and moreover, with lesser toxicity. Our data suggest that consideration might be given to combining anti-angiogenic agents and DTIC using a metronomic regimen, perhaps immediately following up-front conventional DTIC chemotherapy alone or in combination with an antiangiogenic agent. The feasibility of such metronomic chemotherapy might be improved by substituting DTIC (an agent administered intravenously) with orally bio-available agents such as temozolomide, an agent which is equally effective as DTIC in the treatment of malignant melanoma but which also shows superior penetration into the brain parenchyma (2, 30).

It is interesting to note that the effectiveness achieved by the metronomic chemotherapeutic regimens that we have examined (LDM Vbl/LDM CTX in this study and LDM CTX/UFT in previous breast cancer studies) against advanced metastatic disease is often contrasted by their relative ineffectiveness against primary tumors (13, 16). This disparity may be ascribed to differential effects mediated by metronomic therapy against endothelial cells in specific sites (e.g. lung parenchyma metastases vs. subdermal primary tumor). In turn, this divergence in sensitivity may be attributed to the heterogeneity of endothelial cells present in different organ sites, as well as to differences in the microenvironment itself (e.g. presence of distinct growth factors, cytokines, etc.). Given that the primary target of metronomic chemotherapy schedules is presumed to be the endothelial cell population of the neovasculature of the tumor, it reasons that this anti-angiogenic effect can be enhanced by the incorporation of ‘dedicated’ anti-angiogenic agents. In this regard, the effective suppression of both metastatic disease and primary tumor growth that was mediated by the combination of metronomic Vbl and the VEGFR-targeting antibody (DC101) suggests that this combination therapy approach is more effective against tumors growing in different sites.

In addition to the current lack of effective therapies for advanced melanoma metastasis, there are also few alternatives for adjuvant therapy. Presently, IFN-alpha 2b is the only FDA-approved agent for the treatment of melanoma patients who are free of disease but at high risk of recurrence (31). However, despite the initial promise, this agent has been shown to induce only a small improvement on overall survival, moreover this minimal beneficial effect is achieved with high levels of toxicity (31, 32). Given the efficacy and minimal toxicity of the regimens noted herein, consideration should be given to evaluating the efficacy of the metronomic chemotherapy approach in the adjuvant setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported primarily by grants to RSK from the National Institute of Health-USA (CA-41233), the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC), and also by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). R.S. Kerbel holds a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Tumor Biology, Angiogenesis and Antiangiogenic Therapy. The authors would like to thank ImClone Systems for their gift of the VEGFR targeting antibody, DC101.

References

- 1.Comis RL. DTIC (NSC-45388) in malignant melanoma: a perspective. Cancer Treat Rep. 1976;60:165–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middleton MR, Grob JJ, Aaronson N, et al. Randomized phase III study of temozolomide versus dacarbazine in the treatment of patients with advanced metastatic malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:158–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringborg U, Jungnelius U, Hansson J, Strander H. Dacarbazine-vindesine-cisplatin in disseminated malignant melanoma. A phase I-II trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:214–17. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buzaid AC, Murren J. Chemotherapy for advanced malignant melanoma. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1992;21:205–09. doi: 10.1007/BF02591647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman PB, Einhorn LH, Meyers ML, et al. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of the Dartmouth regimen versus dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2745–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eigentler TK, Caroli UM, Radny P, Garbe C. Palliative therapy of disseminated malignant melanoma: a systematic review of 41 randomised clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:748–59. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerbel RS, Kamen BA. The anti-angiogenic basis of metronomic chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:423–36. doi: 10.1038/nrc1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerbel RS, Klement G, Pritchard KI, Kamen B. Continuous low-dose anti-angiogenic/metronomic chemotherapy: from the research laboratory into the oncology clinic. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:12–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermans IF, Chong TW, Palmowski MJ, et al. Synergistic effect of metronomic dosing of cyclophosphamide combined with specific antitumor immunotherapy in a murine melanoma model. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8408–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spieth K, Kaufmann R, Gille J. Metronomic oral low-dose treosulfan chemotherapy combined with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in pretreated advanced melanoma: a pilot study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52:377–82. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia LJ, Wei DP, Sun QM, et al. Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium improves cyclophosphamide chemotherapy at maximum tolerated dose and low-dose metronomic regimens in a murine melanoma model. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:666–74. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reichle A, Bross K, Vogt T, et al. Pioglitazone and rofecoxib combined with angiostatically scheduled trofosfamide in the treatment of far-advanced melanoma and soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2004;101:2247–56. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munoz R, Man S, Shaked Y, et al. Highly efficacious nontoxic preclinical treatment for advanced metastatic breast cancer using combination oral UFT-cyclophosphamide metronomic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3386–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emmenegger U, Morton GC, Francia G, et al. Low-dose metronomic daily cyclophosphamide and weekly tirapazamine: a well-tolerated combination regimen with enhanced efficacy that exploits tumor hypoxia. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1664–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pietras K, Hanahan D. A multitargeted, metronomic, and maximum-tolerated dose “chemo-switch” regimen is antiangiogenic, producing objective responses and survival benefit in a mouse model of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:939–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz-Munoz W, Man S, Xu P, Kerbel RS. Development of a preclinical model of spontaneous human melanoma central nervous system metastasis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4500–05. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lev DC, Ruiz M, Mills L, et al. Dacarbazine causes transcriptional up-regulation of interleukin 8 and vascular endothelial growth factor in melanoma cells: a possible escape mechanism from chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:753–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klement G, Baruchel S, Rak J, et al. Continuous low-dose therapy with vinblastine and VEGF receptor-2 antibody induces sustained tumor regression without overt toxicity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:R15–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI8829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacroix M. MDA-MB-435 cells are from melanoma, not from breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;63:567. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0776-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rae JM, Creighton CJ, Meck JM, et al. MDA-MB-435 cells are derived from M14 melanoma cells--a loss for breast cancer, but a boon for melanoma research. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104:13–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christgen M, Lehmann U. MDA-MB-435: the questionable use of a melanoma cell line as a model for human breast cancer is ongoing. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1355–57. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.9.4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rae JM, Ramus SJ, Waltham M, et al. Common origins of MDA-MB-435 cells from various sources with those shown to have melanoma properties. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21:543–52. doi: 10.1007/s10585-004-3759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellison G, Klinowska T, Westwood RF, et al. Further evidence to support the melanocytic origin of MDA-MB-435. Mol Pathol. 2002;55:294–99. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.5.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan MA, Andrews S, Ismail-Khan R, et al. Overall and progression-free survival in metastatic melanoma: analysis of a single-institution database. Cancer Control. 2006;13:211–17. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerbel RS. Human tumor xenografts as predictive preclinical models for anticancer drug activity in humans: better than commonly perceived-but they can be improved. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:S134–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gogas HJ, Kirkwood JM, Sondak VK. Chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma: time for a change? Cancer. 2007;109:455–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bibby MC. Orthotopic models of cancer for preclinical drug evaluation: advantages and disadvantages. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:852–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Man S, Munoz R, Kerbel RS. On the development of models in mice of advanced visceral metastatic disease for anti-cancer drug testing. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:737–47. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dellapasqua S, Bertolini F, Bagnardi V, et al. Metronomic cyclophosphamide and capecitabine combined with bevacizumab in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4899–905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quirbt I, Verma S, Petrella T, et al. Temozolomide for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Curr Oncol. 2007;14:27–33. doi: 10.3747/co.2007.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawson DH. Choices in adjuvant therapy of melanoma. Cancer Control. 2005;12:236–41. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ascierto PA, Kirkwood JM. Adjuvant therapy of melanoma with interferon: lessons of the past decade. J Transl Med. 2008;6:62. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]