Summary

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) has evolved remarkable mechanisms that favor viral persistence by interfering with host innate and adaptive immune responses. These same mechanisms are likely to contribute to resistance to exogenously administered interferon used for HCV treatment. We review the host innate and adaptive immune responses in the context of HCV infection as well as the strategies by which these responses are subverted by the virus. In addition, the contribution of host factors, such as race and insulin resistance, to interferon nonresponsiveness is discussed. Our progress in understanding the molecular underpinnings of interferon treatment failure in HCV infection has resulted in several promising and novel treatment strategies for HCV treatment nonresponders.

Keywords: hepatitis C, interferon, treatment, race, immune system

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection results in chronic infection in approximately 80% of exposed individuals. The high frequency of HCV chronicity as an outcome of exposure is striking, as HCV is an RNA virus with no DNA intermediate and no ability to integrate into the host genome in a latent form. It is therefore clear that HCV has evolved remarkable mechanisms to assure its persistence in the infected host, despite innate and adaptive host antiviral responses.

Type I interferon signaling is pivotal to the innate immune response, and exogenously administered interferon treatment regimens are the current standard of care for the treatment of chronic HCV infection. However, the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin is effective in only about 50% of all patients with HCV infection. Given the critical role for type I interferons in innate immunity against HCV, it is likely that the mechanisms that favor viral chronicity also contribute to nonresponse to interferon-based therapy.

Type I interferon and the innate immune response to HCV infection

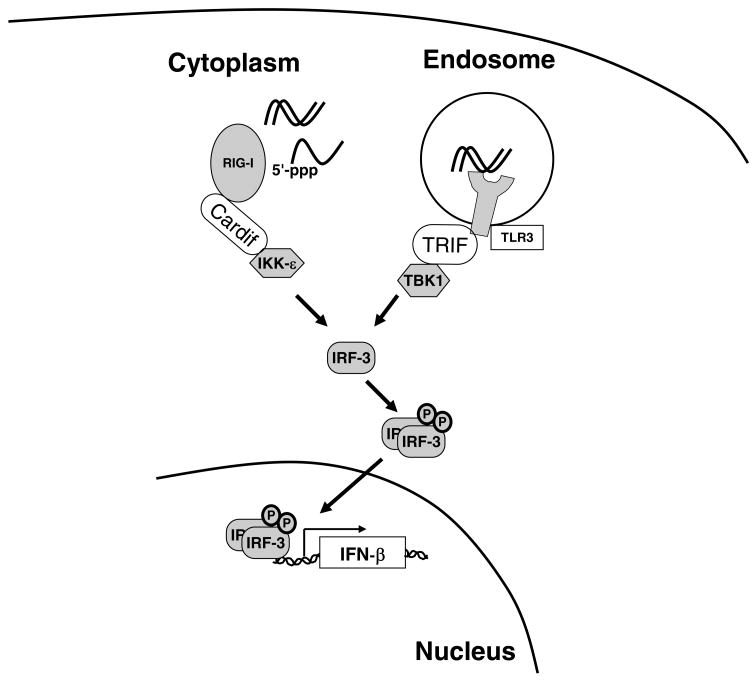

Innate immunity to the hepatitis C virus is triggered by activation of cellular sensors that recognize the presence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns, or PAMPs. The two key cellular sensors in the context of HCV infection are Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), which senses double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) within endosomes, and the RNA helicase RIG-I, which senses intracellular double-stranded RNA or single-stranded viral RNA flanked by a 5′-triphosphate (Figure 1). Signaling initiated by TLR3 and RIG-I is transmitted through the adaptor proteins TRIF and Cardif (also known as IPS-1, VISA, or MAVS), respectively, to converge on the transcription factors IRF3 and NF-κB. IRF3 is phosphorylated by IKKε and TBK1, resulting in its dimerization and nuclear translocation.

Figure 1. Recognition of HCV RNA by RIG-I and TLR3 and activation of type I interferon transcription.

The event that is believed to trigger the innate immune response to HCV infection is the recognition of one or more pathogen-associated molecular patterns encoded in the HCV RNA. TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) within endosomes and in turn activates the protein kinase TBK1 through the adaptor protein TRIF. RIG-I preferentially recognizes single-stranded RNA with a terminal 5′-triphosphate (ppp) over dsRNA. RIG-I activates the protein kinase IKKε through the Cardif adaptor protein. Both TBK1 and IKKε phosphorylate the transcription factor IRF-3, which leads to its homodimerization, nuclear translocation, and stimulation of interferon-β gene transcription. The HCV nonstructural protein NS3-4A specifically cleaves TRIF and Cardif, thus blocking the innate immune recognition of HCV infection.

Activated IRF3 and NF-κB translocate to the nucleus where they activate interferon-β gene transcription. Secreted interferon-β acts in both an autocrine and paracrine manner to stimulate the interferon-α/β receptor tyrosine kinase (IFNAR), which is a heterodimer of IFNAR-1 and IFNAR-2. The activated receptor recruits and phosphorylates the tyrosine kinases Jak1 and Tyk2, which in turn phosphorylate STAT1 and STAT2. Phosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2 combine with IRF9 to form the heterotrimeric transcription factor known as ISGF3. ISGF3 binds to the interferon-stimulated response element upstream of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) to promote their transcription. One of these ISGs is IRF-7, which amplifies interferon-α and -β transcription (1), thus generating a positive feedback loop for the amplification of type I interferon signaling.

The pathway of endogenous type I interferon signaling outlined above is the same as that used by exogenously administered interferon-α for the treatment of HCV infection. Namely, pharmacologic doses of interferon-α activate the Jak-STAT signal transduction pathway through IFNAR binding and ultimately stimulate ISG transcription.

Microarray studies have identified over 200 ISGs with diverse functions. Many of these, such as the dsRNA dependent protein kinase (PKR), 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS), and myxovirus resistance 1 (Mx1) are known to have direct antiviral functions.

Interferon and the adaptive immune response to HCV

In addition to its crucial role in regulating innate antiviral immunity, type I interferon also enhances the adaptive immune response to HCV. For example, immunoproteasome subunits are induced by type I interferon, which stimulates antigen processing and thus may enhance the adaptive immune response to HCV infection (2). Furthermore, type I interferon stimulates the proliferation of memory T cells (3), enhances dendritic cell differentiation (4, 5), and upregulates class I MHC expression on hepatocytes (6). Type I interferons, therefore, exert their antiviral effects on HCV both through direct antiviral mechanisms as well as indirect immunomodulatory mechanisms.

Resistance of HCV to interferon

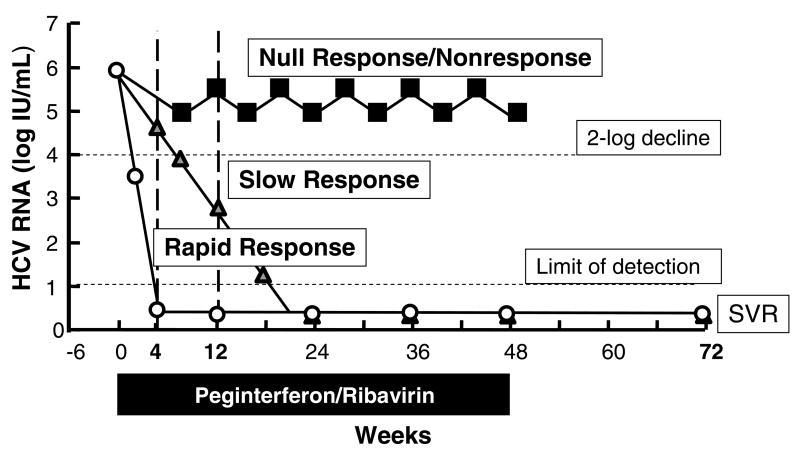

Although we have made great strides in the therapy of chronic HCV infection, the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin is able to produce a sustained virologic response (SVR) in only about 55% of all patients (7, 8). The response of the HCV viral load to therapy is often divided into three categories (Figure 2). A null response is conventionally defined as a decline in HCV viral load by less than 2 log10 at 12 weeks, while a partial or slow response denotes a decline in HCV RNA by over 2 log10 but with detectable viremia at week 12 and clearance only by week 24. Slow responders have a lower chance of attaining a SVR compared to complete early responders, who have undetectable serum HCV RNA at 12 weeks, or rapid responders, who have lost detectable RNA by 4 weeks of treatment.

Figure 2. Classification of interferon response and nonresponse.

This plot depicts three different possible responses of the HCV serum RNA titer to interferon-based therapy in a hypothetical patient with genotype 1 HCV infection. A null response or nonresponse (black squares) is conventionally defined by a failure of the HCV RNA titer to fall by at least 2 log10 by 12 weeks of treatment. The most commonly used definition of a slow response (grey triangles) is a fall of the HCV RNA by at least 2 log10 by 12 weeks of treatment but detectable viremia that then clears by week 24. A rapid response (white circles) indicates that the HCV RNA is undetectable at 4 weeks of treatment by the most sensitive available test (typically quantitative RT-PCR based methods) with a typical threshold of 10 IU/mL. Rapid response is highly predictive of an eventual sustained virologic response (SVR) at 24 weeks after the end of therapy.

Current interferon-based therapy fails to work in so many patients likely because of a combination of viral and host factors. Virally encoded proteins directly inhibit innate immunity and may also inhibit adaptive immunity (Table 1). It is also known that there are fixed host factors that are associated with treatment responsiveness, such as race and age (9). Additional modifiable host factors such as obesity, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis may adversely affect the outcome of treatment.

Table 1.

Suppression of innate and adaptive immune responses by HCV structural and nonstructural proteins

Interestingly, it should be pointed out that patients with acute HCV infection experience far higher rates of SVR (80–90%) when treated within 12 weeks of diagnosis by standard interferon-based regimens than those with chronic infection (10, 11), indicating that the viral and host mechanisms that contribute to interferon nonresponse take time to become established during the acute or early stages of HCV infection.

Molecular mechanisms of viral interference with innate immunity

As described above, the HCV PAMP sensors RIG-I and TLR3 signal through the adaptor proteins Cardif and TRIF, respectively (Figure 1). Remarkably, the HCV NS3-4A serine protease specifically cleaves both Cardif (12, 13) and TRIF (14) to inactivate signals initiated by RIG-I and TLR3.

Specific NS3-4A protease inhibitors, therefore, not only directly inhibit the HCV lifecycle by inhibiting cleavage of the HCV polypeptide, but may also rescue the NS3-4A mediated block of RIG-I and TLR3 signaling and hence restore the innate immune pathway in infected hepatocytes.

In addition to the effect of NS3-4A on blocking events upstream of interferon-β transcription, there is evidence that other HCV proteins block interferon signaling downstream of the interferon-α/β receptor itself. Overexpression of HCV core protein leads to induction of SOCS (Suppressors of Cytokine Signaling) 3 protein (15), which in turn inhibits STAT1 phosphorylation by Jak1. We have shown that HCV core also appears to directly inhibit STAT1 by directly binding the STAT1 SH2 domain, leading to STAT1 proteasome-dependent degradation as well as inhibition of STAT1 phosphorylation (16, 17). Core protein has been shown to act at yet another level to inhibit type I interferon signaling through the upregulation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). PP2A, in turn, inhibits protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1), leading to hypomethylation of STAT1. Hypomethylated STAT1 binds to the inhibitory Protein Inhibitor of Activated STAT (PIAS1), which prevents STAT1 from activating ISG transcription (18). Collectively, these mechanisms all lead to the attenuation of ISG expression by HCV in response to endogenous or exogenous interferon.

Finally, the antiviral effects of several ISGs are also blunted by HCV via diverse mechanisms. NS5A and the envelope protein E2 directly interact with and repress PKR, an antiviral ISG (19, 20). Another antiviral ISG, 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase, activates RNAse L to cleave double-stranded RNA within predicted stem-loop structures. One study found that genotype 2a HCV RNA had more predicted RNAse L cleavage sites than genotype 1a or 1b sequences and was more readily cleaved in cell extracts (21). Moreover, HCV RNA isolated from patients on interferon therapy had acquired mutations resulting in the loss of predicted RNAse L cleavage sites. However, it has not been shown that the loss of such cleavage sites is associated with interferon nonresponse, and therefore the functional significance of these observations remains uncertain.

Viral interference with adaptive immunity

In addition to the well described evasion of innate immunity by HCV, there is some evidence that HCV circumvents the adaptive immune response. Dendritic cells recovered from the peripheral blood of individuals with chronic HCV have impaired allostimulatory capacity (22) and also possess an immature phenotype compared to dendritic cells from healthy donors or those who had cleared HCV infection (23). HCV core protein has been shown to inhibit T-cell proliferative responses in vitro through a direct interaction with the gC1q receptor (24), while CD8+ T-cell differentiation and function also appear to be impaired in HCV infection (25, 26).

The highly error-prone HCV RNA polymerase gives rise to a large number of HCV quasispecies within the infected individual. Viral escape from CD8+ T-cell responses occurs by mutations within T-cell epitopes (27) and is likely to be yet another mechanism by which HCV is able to evade the adaptive immune response.

Fixed host factors and interferon nonresponse in HCV infection

It is clear that host factors are also important contributors to HCV treatment responsiveness. Broadly speaking, we can divide host factors into fixed and modifiable factors. The strongest known fixed host factor for HCV treatment response is race. Three studies comparing the effect of peginterferon and ribavirin in African-Americans (AA) versus Caucasian-Americans (CA) have consistently demonstrated that AA with genotype 1 HCV infection achieve an SVR at rates significantly lower (19–28%) than CA (39–52%) by nearly a factor of two, even after correcting for medication adherence and peginterferon pharmacokinetics (28–31).

An important clue to the mechanism(s) that underlie the inferiority of interferon response in AA can be gleaned from the viral kinetics in treated patients. In the Virahep-C study (30), significantly fewer AA had an undetectable HCV viral load (<50 IU/mL) compared to CA at week 4 after start of therapy (10% versus 22%), and this difference was seen at all of the subsequent time points, such that the overall SVR was only 28% in AA versus 52% in CA. However, when analyzed by rapid virologic responder (RVR) status (i.e. undetectable HCV RNA at week 4), those who had attained an RVR were equally likely to achieve an SVR regardless of race. Much of the difference in SVR between AA and CA could be explained by the difference in frequency of achievement of rapid and early virologic response in the two groups, suggesting that the increased rate of treatment failure among AA might be a result of intrinsic defects in innate or adaptive immunity. An important corollary of these findings is that on-treatment responses (i.e. RVR) appear to supersede baseline factors of responsiveness.

One major effector of the innate immune response is the transcription of interferon-stimulated genes. Another study from the Virahep-C cohort using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) found that the number of genes whose expression levels changed by at least 1.5-fold with a p-value of <0.001 during peginterferon/ribavirin treatment was significantly higher in marked responders (>3.5 log10 decrease at 4 weeks of treatment) compared to poor responders (<1.4 log10 decrease) (32), suggesting that poor responders had a blunted response to interferon at the gene transcription level. Among the upregulated gene transcripts were many well-known antiviral ISGs such as OAS1 and Mx1. Surprisingly, AA patients had a higher number of genes whose expression was significantly altered (upregulated or downregulated) by treatment compared to CA among marked responders as well as among poor responders.

In addition to blunted innate immune responses to interferon in AA, adaptive immunity also appears to be impaired in AA. HCV-specific CD4+ T cell responses were measured by interferon-gamma secretion and were found to be impaired in AA compared to CA in the Virahep-C cohort, while CMV-specific responses were similar between the two groups. Furthermore, stronger pretreatment HCV-specific CD4+ responses were independently associated with SVR (33).

The possible viral contribution to nonresponse has been examined by direct sequencing of the full pretreatment HCV genome from rapid responders versus nonresponders in the Virahep-C cohort (34); this study failed to identify significant viral sequence clustering among isolates when analyzed by viral response or race, indicating that nonresponders and AA are not infected by distinct strains of HCV when compared to responders and CA, respectively. However, there appeared to be more sequence diversity (compared to reference HCV sequences) in certain viral genes in rapid responders than in null responders, and in genotype 1b (but not 1a) CA versus AA, even after taking known T-cell epitopes into account.

We have discussed the findings by Taylor et al. in peripheral blood mononuclear cells that poor responders had blunted interferon-stimulated gene expression compared to marked responders; do these findings hold true in the liver, where HCV resides? Several studies have examined the relationship between HCV treatment nonresponse and gene expression in the liver (35–37). In the study by Chen et al., expression profiling of pretreatment liver biopsies from patients with chronic HCV infection identified 18 genes whose expression differed significantly between responders (undetectable HCV RNA at the first post-treatment assessment) and nonresponders (detectable HCV RNA at end of treatment). Among these were many ISGs, as expected. What was unexpected was the finding that many of these ISGs were actually upregulated in pretreatment biopsies from nonresponders compared to responders. Subsequent studies by Feld et al. and Sarasin-Filipowicz et al. have confirmed the general finding that treatment nonresponse is associated with broad baseline ISG transcriptional upregulation.

Sarasin-Filipowicz et al. were able to evaluate expression profiles in paired liver biopsies from 16 patients obtained before and 4 hours after a single dose of peginterferon. A key finding was that the great majority (~93%) of ISGs were expressed at the same absolute levels in post-treatment biopsies in 4-week responders versus nonresponders. However, nonresponders displayed minimal ISG induction over baseline because baseline ISG expression was already broadly elevated. Another important point was that preactivation of ISGs was not observed in PBMCs from the same patients, indicating that baseline ISG preactivation in nonresponders is specific to the liver. It appears, therefore, that it is the fold change of ISG induction over baseline in response to interferon that is associated with treatment response, rather than the absolute magnitude of ISG expression in response to interferon.

A similar observation has been made in HCV infected chimpanzees, namely, that several ISGs were basally upregulated in the livers of HCV-infected chimpanzees compared to uninfected controls (38). They further showed that in contrast to the basal upregulation of ISGs in HCV-infected chimpanzee liver, their transcriptional induction by exogenous interferon was impaired compared to uninfected controls.

We are therefore left with the observations that ISG expression is elevated in HCV treatment nonresponders at baseline and that HCV infection may blunt the further induction of ISGs by exogenous interferon; however, elevated basal ISG expression in nonresponders is clearly ineffective from the standpoint of viral clearance. One potential explanation for why this might be comes from expression profiling of liver biopsies from humans at 24 hours following a single dose of peginterferon-alfa compared to control pretreatment biopsies from a different set of individuals (38). The investigators examined expression of SOCS3, which was discussed earlier in this review and is thought to inhibit type I interferon signaling by blocking STAT1 phosphorylation. Expression of SOCS3 decreased in both rapid responders and nonresponders after a single dose of peginterferon; however, this decrease was significantly greater in responders (defined as > 2 log10 decline in HCV RNA at week 4 of treatment) than in slow responders (< 2 log10 decline).

How can we reconcile the data from these expression profiling studies? First, it appears that ISG transcript levels are basally elevated in nonresponder liver tissue compared to responders, though the elevated antiviral ISGs are clearly inadequate on their own to clear HCV infection. Second, further elevation in hepatic ISG transcript levels in response to exogenous interferon is blocked in nonresponders. It is conceivable that the observed blunting of hepatic ISG induction by exogenous interferon in nonresponders is mediated in part by inhibitory proteins such as SOCS3. However, the elevated basal ISG expression in nonresponders suggests that there are additional blocks at the level of ISG action; these blocks may be viral or host-mediated.

An important question is whether host genetic polymorphisms are associated with interferon treatment response in chronic HCV infection. A candidate gene analysis was used to study 118 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from ISGs and interferon signaling pathway genes in individuals from the Virahep-C cohort for associations with SVR (39). Three SNPs from the OASL (OAS-like) gene were found to be weakly associated with SVR, though this study was limited by a small sample size (n=374). We anticipate that adequately powered whole genome association studies will be necessary to identify host genetic markers that modify interferon sensitivity and HCV persistence.

Modifiable host factors and interferon nonresponse in HCV infection

In addition to fixed host factors such as race, modifiable risk factors contribute to interferon nonresponse. Multivariate analysis of the Virahep-C cohort found that the HOMA index, a measure of insulin resistance, was independently associated with SVR (40). Although insulin resistance was more prevalent among AA compared to CA, this alone did not account for the differences in SVR between the two groups. The HOMA index had also been found to correlate with treatment response in a previous study of genotype 1-infected patients treated with peginterferon and ribavirin (41). In that study, patients with a normal HOMA (<2) had an SVR of 60.5%, compared to an SVR of 40% in patients with moderate insulin resistance (HOMA 2-4) and only 20% in patients with severe insulin resistance (HOMA >4).

One mechanism by which insulin resistance and obesity may contribute to interferon nonresponse is through upregulation of SOCS3 (42). SOCS3 blocks interferon signaling and also may exacerbate insulin resistance by promoting ubiquitin-mediated degradation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) 1 and 2 (43). However, it remains an open question as to whether reversal of insulin resistance results in higher rates of HCV treatment response in vivo. Clinical trials are underway to determine whether adding pharmacologic insulin sensitizers, such as thiazolidinediones, to standard HCV therapy will increase SVR.

Finally, there have been studies that claim to show the presence of interferon-neutralizing antibodies in the serum of patients with chronic HCV infection treated with interferon. One study found neutralizing antibodies to interferon in 39% of patients experiencing virologic breakthrough on interferon monotherapy (44). Such a high incidence of neutralizing antibodies on interferon therapy has not been reported in other studies. Another study identified neutralizing antibodies to interferon in 14% of patients treated with interferon monotherapy; there was no significant association, however, between the presence of neutralizing antibodies and treatment response (45).

Overcoming barriers to interferon nonresponse in HCV infection

The significant progress made thus far in understanding the viral and host factors that contribute to treatment nonresponse indicate several routes by which these barriers may be overcome (Table 2). With regard to viral factors, the NS3-4A protease is an excellent therapeutic target due to its essential role in the HCV life cycle as well as its role in inactivation of intracellular innate immune responses. Indeed, NS3-4A protease inhibitors reverse Cardif and TRIF cleavage in liver biopsy samples from HCV-infected patients (D. Moradpour, personal communication). The high efficacy of NS3-4A protease inhibitors in clinical trials could potentially be explained by their ability to restore innate immune signaling in addition to their known direct antiviral effects. It should be noted that a number of potent NS5B polymerase inhibitors have demonstrated antiviral efficacies in vitro and in vivo on par with NS3-4A inhibitors. These findings raise the possibility that any potent direct antiviral agent could liberate innate immunity through its reduction of viral protein levels. A recent report comparing two NS3-4A protease inhibitors with a nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitor found that the polymerase inhibitor was unable to rescue interferon-beta promoter activation in response to challenge with Sendai virus in cell culture systems of HCV infection (46). The protease inhibitors did rescue interferon-beta promoter activation but only at concentrations 100-fold higher than the antiviral EC50. However, it should be pointed out that NS3-4A protein expression was only partially abolished by the agents tested in this study due to the short treatment duration (52 hours), and it remains possible that interferon responsiveness can be restored by longer duration of direct antiviral therapy that more effectively suppresses viral protein expression. Regardless, the best test of whether direct antiviral inhibitors can restore interferon responsiveness is being carried out in clinical trials of NS3-4A protease inhibitors in prior peginterferon/ribavirin nonresponders; early data from such trials suggest that on-treatment responses and SVR can be achieved in a large portion of prior nonresponders.

Table 2.

Possible approaches to overcoming interferon resistance

| Approach | Proposed mechanism(s) |

|---|---|

| NS3-4A protease inhibitors | Inhibition of Cardif and TRIF cleavage by NS3-4A and restoration of interferon β activation (12–14) |

| S-adenosyl-L-methionine and betaine | Restoration of STAT1 methylation and rescue from PIAS1 inhibition (47) |

| High-dose ribavirin | Interferon sensitization by increasing ISG expression and decreasing expression of inhibitors of interferon signaling (36) |

| Reversal of insulin resistance | Decreasing SOCS3 expression (42) |

| Targeting host cofactors of HCV lifecycle |

Another potential means of overcoming interferon nonresponse might be to give higher doses of exogenous interferon or to use interferon variants with more favorable pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics. It appears, however, that high-dose interferon or interferon variants such as albumin-interferon or consensus interferon do not confer clinically significant benefits over standard therapy in nonresponders. Furthermore, many of these regimens are associated with significant toxicities. Our experience to date, therefore, suggests that the downstream blocks to interferon response imposed by viral and host factors cannot be circumvented simply by overwhelming them with higher doses of interferon.

How might we rescue these downstream defects? One approach might be to activate ISGs through interferon-independent mechanisms; further work would be necessary to identify the key effector antiviral ISGs among the many that have been identified to date. A second would be to reverse the effects of HCV on Jak-STAT signaling pathway members, such as hypomethylation of STAT1 described earlier in this review. S-adenosyl-L-methionine and betaine can restore STAT1 methylation (47) and therefore might act as interferon enhancers. Yet another approach is to block inhibitors of interferon signaling such as SOCS3.

The anti-HCV actions of ribavirin

The antiviral mechanism of ribavirin remains somewhat controversial. The current prevailing hypothesis is that ribavirin acts as a mutagen to increase the likelihood of lethal mutations (“error catastrophe”) in the HCV genome, while other evidence supports a possible immune modulatory activity. These two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. One study found an increase in HCV mutation frequency in HCV replicon cell lines treated with ribavirin, as well as in patients treated with ribavirin monotherapy but not in those receiving combination peginterferon and ribavirin, in whom the mutation frequency actually fell on treatment (48). Another study also identified an increase in HCV mutation frequency in humans treated with ribavirin monotherapy at 4 weeks but not at 24 weeks of treatment (49). Finally, a third study in patients receiving ribavirin monotherapy followed by combination interferon/ribavirin treatment did not reveal any detectable increase in HCV mutations (50). Evidence that ribavirin may modulate the innate immune response comes from a tissue expression profiling study of liver biopsies from patients treated with a single dose of peginterferon with or without ribavirin, compared to those from matched untreated controls. It was shown that the addition of ribavirin increased expression levels of several ISGs and also decreased several negative regulators of interferon signaling such as PP2A and SOCS1 (36). Ribavirin may therefore be acting as an interferon “sensitizer”.

In contrast to the relative ineffectiveness of increasing interferon dose for HCV treatment, there is evidence that higher doses of ribavirin may be superior to the current recommended ribavirin dosing regimens. A recent randomized study compared “higher-dose” weight-based ribavirin (15.2 mg/kg/d) plus epoetin alfa to “standard” weight-based dosing (13.3 mg/kg/d) with or without epoetin alfa in genotype 1, treatment-naïve patients (51). The authors found that the high-dose group had a significantly better SVR than the standard groups (49% versus 34% and 22%) due to a significantly lower relapse rate in the high-dose group (8% versus 38%).

Another avenue: targeting host cofactors

A very promising strategy to overcome viral resistance to current therapy is to identify and target host proteins that support the HCV life cycle. For example, the human protein cyclophilin B interacts with the genotype 1 NS5B HCV RNA polymerase to stimulate binding to RNA (52). The cyclophilin B inhibitor Debio-025 potently suppresses genotype 1 HCV replication in vivo (53). Another example of a “drugable” host cofactor is FBL2, which requires lipid modification by geranylgeranylation for its function (54). HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors disrupt geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthesis and inhibit HCV replication in cell culture models (55). Thus, host lipid biosynthesis inhibitors may be another method of blocking HCV replication. On the one hand, targeting host cofactors of the HCV life cycle is attractive because it imposes a higher genetic barrier for resistance than direct antiviral compounds. However, the principal drawback of this strategy is the greater potential for cellular toxicity.

Conclusion

In summary, HCV has evolved elaborate and broad mechanisms to disarm both host innate and adaptive immunity. These mechanisms favor viral persistence even in the face of exogenous interferon-based therapies. Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which HCV counteracts the host immune response will yield novel therapeutic strategies. In addition, host factors such as race and insulin resistance have substantial impact on treatment responsiveness. We anticipate that additional host factors such as genetic polymorphisms in interferon-signaling genes and ISGs will be identified as modulators of HCV treatment response. Modification of adverse host factors, where possible, may be another opportunity to optimize HCV therapy.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Numbers AI080122 (to A.W.T.), AI069939, and DK078772 (to R.T.C.) from the National institutes of Health as well as by a Tosteson Posdoctoral Fellowship from the Massachusetts Biomedical Research Corporation (to A.W.T.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wathelet MG, Lin CH, Parekh BS, Ronco LV, Howley PM, Maniatis T. Virus infection induces the assembly of coordinately activated transcription factors on the IFN-beta enhancer in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;1:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin EC, Seifert U, Kato T, Rice CM, Feinstone SM, Kloetzel PM, et al. Virus-induced type I IFN stimulates generation of immunoproteasomes at the site of infection. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3006–3014. doi: 10.1172/JCI29832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tough DF, Borrow P, Sprent J. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science. 1996;272:1947–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luft T, Pang KC, Thomas E, Hertzog P, Hart DN, Trapani J, et al. Type I IFNs enhance the terminal differentiation of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:1947–1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santini SM, Lapenta C, Logozzi M, Parlato S, Spada M, Di Pucchio T, et al. Type I interferon as a powerful adjuvant for monocyte-derived dendritic cell development and activity in vitro and in Hu-PBL-SCID mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1777–1788. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willberg CB, Ward SM, Clayton RF, Naoumov NV, McCormick C, Proto S, et al. Protection of hepatocytes from cytotoxic T cell mediated killing by interferon-alpha. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL, Jr, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kau A, Vermehren J, Sarrazin C. Treatment predictors of a sustained virologic response in hepatitis B and C. J Hepatol. 2008;49:634–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamal SM, Fouly AE, Kamel RR, Hockenjos B, Al Tawil A, Khalifa KE, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b therapy in acute hepatitis C: impact of onset of therapy on sustained virologic response. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:632–638. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiegand J, Buggisch P, Boecher W, Zeuzem S, Gelbmann CM, Berg T, et al. Early monotherapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b for acute hepatitis C infection: the HEP-NET acute-HCV-II study. Hepatology. 2006;43:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, Bartenschlager R, et al. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;437:1167–1172. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XD, Sun L, Seth RB, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Hepatitis C virus protease NS3/4A cleaves mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein off the mitochondria to evade innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17717–17722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508531102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li K, Foy E, Ferreon JC, Nakamura M, Ferreon AC, Ikeda M, et al. Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the Toll-like receptor 3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2992–2997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408824102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bode JG, Ludwig S, Ehrhardt C, Albrecht U, Erhardt A, Schaper F, et al. IFN-alpha antagonistic activity of HCV core protein involves induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-3. FASEB J. 2003;17:488–490. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0664fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin W, Choe WH, Hiasa Y, Kamegaya Y, Blackard JT, Schmidt EV, et al. Hepatitis C virus expression suppresses interferon signaling by degrading STAT1. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1034–1041. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin W, Kim SS, Yeung E, Kamegaya Y, Blackard JT, Kim KA, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein blocks interferon signaling by interaction with the STAT1 SH2 domain. J Virol. 2006;80:9226–9235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00459-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duong FH, Filipowicz M, Tripodi M, La Monica N, Heim MH. Hepatitis C virus inhibits interferon signaling through up-regulation of protein phosphatase 2A. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:263–277. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gale M, Jr, Korth MJ, Tang NM, Tan SL, Hopkins DA, Dever TE, et al. Evidence that hepatitis C virus resistance to interferon is mediated through repression of the PKR protein kinase by the nonstructural 5A protein. Virology. 1997;230:217–227. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor DR, Shi ST, Romano PR, Barber GN, Lai MM. Inhibition of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR by HCV E2 protein. Science. 1999;285:107–110. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han JQ, Barton DJ. Activation and evasion of the antiviral 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase/ribonuclease L pathway by hepatitis C virus mRNA. RNA. 2002;8:512–525. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202020617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanto T, Hayashi N, Takehara T, Tatsumi T, Kuzushita N, Ito A, et al. Impaired allostimulatory capacity of peripheral blood dendritic cells recovered from hepatitis C virus-infected individuals. J Immunol. 1999;162:5584–5591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auffermann-Gretzinger S, Keeffe EB, Levy S. Impaired dendritic cell maturation in patients with chronic, but not resolved, hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 2001;97:3171–3176. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kittlesen DJ, Chianese-Bullock KA, Yao ZQ, Braciale TJ, Hahn YS. Interaction between complement receptor gC1qR and hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits T-lymphocyte proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1239–1249. doi: 10.1172/JCI10323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francavilla V, Accapezzato D, De Salvo M, Rawson P, Cosimi O, Lipp M, et al. Subversion of effector CD8+ T cell differentiation in acute hepatitis C virus infection: exploring the immunological mechanisms. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:427–437. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruener NH, Lechner F, Jung MC, Diepolder H, Gerlach T, Lauer G, et al. Sustained dysfunction of antiviral CD8+ T lymphocytes after infection with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2001;75:5550–5558. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5550-5558.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timm J, Lauer GM, Kavanagh DG, Sheridan I, Kim AY, Lucas M, et al. CD8 epitope escape and reversion in acute HCV infection. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1593–1604. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muir AJ, Bornstein JD, Killenberg PG Atlantic Coast Hepatitis Treatment Group. Peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in blacks and non-Hispanic whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2265–2271. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeffers LJ, Cassidy W, Howell CD, Hu S, Reddy KR. Peginterferon alfa-2a (40 kd) and ribavirin for black American patients with chronic HCV genotype 1. Hepatology. 2004;39:1702–1708. doi: 10.1002/hep.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conjeevaram HS, Fried MW, Jeffers LJ, Terrault NA, Wiley-Lucas TE, Afdhal N, et al. Peginterferon and ribavirin treatment in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C genotype 1. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:470–477. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howell CD, Dowling TC, Paul M, Wahed AS, Terrault NA, Taylor M, et al. Peginterferon pharmacokinetics in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:575–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor MW, Tsukahara T, Brodsky L, Schaley J, Sanda C, Stephens MJ, et al. Changes in gene expression during pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus distinguish responders from nonresponders to antiviral therapy. J Virol. 2007;81:3391–3401. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02640-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosen HR, Weston SJ, Im K, Yang H, Burton JR, Jr, Erlich H, et al. Selective decrease in hepatitis C virus-specific immunity among African Americans and outcome of antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2007;46:350–358. doi: 10.1002/hep.21714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donlin MJ, Cannon NA, Yao E, Li J, Wahed A, Taylor MW, et al. Pretreatment sequence diversity differences in the full-length hepatitis C virus open reading frame correlate with early response to therapy. J Virol. 2007;81:8211–8224. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00487-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Borozan I, Feld JJ, Sun J, Tannis LL, Coltescu C, et al. Hepatic gene expression discriminates responders and nonresponders in treatment of chronic hepatitis C viral infection. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feld JJ, Nanda S, Huang Y, Chen W, Cam M, Pusek SN, et al. Hepatic gene expression during treatment with peginterferon and ribavirin: Identifying molecular pathways for treatment response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1548–1563. doi: 10.1002/hep.21853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarasin-Filipowicz M, Oakeley EJ, Duong FH, Christen V, Terraciano L, Filipowicz M, et al. Interferon signaling and treatment outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7034–7039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707882105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y, Feld JJ, Sapp RK, Nanda S, Lin JH, Blatt LM, et al. Defective hepatic response to interferon and activation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:733–744. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su X, Lee LJ, Im K, Rhodes SL, Tang Y, Tong X, et al. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in interferon signaling pathway genes and interferon-stimulated genes with the response to interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2008;49:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conjeevaram HS, Kleiner DE, Everhart JE, Hoofnagle JH, Zacks S, AFdhal NH, et al. Race, insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;45:80–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romero-Gómez M, Del Mar Viloria M, Andrade RJ, Salmerón J, Diago M, Fernández-Rodríguez CM, et al. Insulin resistance impairs sustained response rate to peginterferon plus ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:636–641. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh MJ, Johnsson JR, Richardson MM, Lipka GM, Purdie DM, Clouston AD, et al. Non-response to antiviral therapy is associated with obesity and increased hepatic expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS-3) in patients with chronic hepatitis C, viral genotype 1. Gut. 2006;55:529–535. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawaguchi T, Yoshida T, Harada M, Hisamoto T, Nagao Y, Ide T, et al. Hepatitis C virus down-regulates insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 through up-regulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1499–1508. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63408-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leroy V, Baud M, de Traversay C, Maynard-Muet M, Lebon P, Zarski JP. Role of anti-interferon antibodies in breakthrough occurrence during alpha 2a and 2b therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1998;28:375–381. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou C, Chuang WL, Yu ML, Dai CY, Chen SC, Lin ZY, et al. Incidence and associated factors of neutralizing anti-interferon antibodies among chronic hepatitis C patients treated with interferon in Taiwan. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1288–1293. doi: 10.1080/003655200453647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang Y, Ishida H, Lenz O, Lin TI, Nyanguile O, Simmen K, et al. Antiviral Suppression vs Restoration of RIG-I Signaling by Hepatitis C Protease and Polymerase Inhibitors. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1710–1718. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duong FH, Christen V, Filipowicz M, Heim MH. S-Adenosylmethionine and betaine correct hepatitis C virus induced inhibition of interferon signaling in vitro. Hepatology. 2006;43:796–806. doi: 10.1002/hep.21116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hofmann WP, Polta A, Herrmann E, Mihm U, Kronenberger B, Sonntag T, et al. Mutagenic effect of ribavirin on hepatitis C nonstructural 5B quasispecies in vitro and during antiviral therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:921–930. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutchman G, Danehower S, Song BC, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH, Thomson M, et al. Mutation rate of the hepatitis C virus NS5B in patients undergoing treatment with ribavirin monotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1757–1766. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chevaliez S, Brillet R, Lázaro E, Hézode C, Pawlotsky JM. Analysis of ribavirin mutagenicity in human hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81:7732–7741. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00382-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shiffman ML, Salvatore J, Hubbard S, Price A, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 with peginterferon, ribavirin, and epoetin alpha. Hepatology. 2007;46:371–379. doi: 10.1002/hep.21712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watashi K, Ishii N, Hijikata M, Inoue D, Murata T, Miyanari Y, et al. Cyclophilin B is a functional regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Mol Cell. 2005;19:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flisiak R, Horban A, Gallay P, Bobardt M, Selvarajah S, Wiercinska-Drapalo A, et al. The cyclophilin inhibitor Debio-025 shows potent anti-hepatitis C effect in patients coinfected with hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus. Hepatology. 2008;47:817–826. doi: 10.1002/hep.22131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang C, Gale M, Jr, Keller BC, Huang H, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, et al. Identification of FBL2 as a geranylgeranylated cellular protein required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Mol Cell. 2005;18:425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ye J, Wang C, Sumpter R, Jr, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Gale M., Jr Disruption of hepatitis C virus RNA replication through inhibition of host protein geranylgeranylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15865–15870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237238100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]