Abstract

This study used a new measure to examine how different types of reasons for cohabitation were associated with individual well-being and relationship quality in a sample of 120 cohabiting heterosexual couples (N = 240). Spending more time together and convenience were the most strongly endorsed reasons. The degree to which individuals reported cohabiting to test their relationships was associated with more negative couple communication and more physical aggression as well as lower relationship adjustment, confidence, and dedication. Testing the relationship was also associated with higher levels of attachment insecurity and more symptoms of depression and anxiety. Men were more likely than women to endorse testing their relationships and less likely to endorse convenience as a reason for cohabiting.

The rates of cohabitation have increased dramatically in the past several decades and this major shift in family demography has important implications for both couples and children (Bumpass & Lu, 2000). Many young adults believe cohabitation is a good way to test their relationships prior to marriage (Axinn & Thornton, 1992; Johnson et al., 2002) and such beliefs about cohabitation likely influence individuals’ choices about cohabitation. However, little research has examined individuals’ own reasons for cohabiting and how those reasons may be related to how they describe themselves and their relationships.

Qualitative work by Manning and Smock (2005) has focused on the process of transitioning into cohabitation and indicates that few people make a deliberate decision to begin cohabitation. Instead, it seems to happen gradually, often without clear communication between partners about the meaning of the transition (Manning & Smock, 2005). Research from Australia suggests that when asked about how they started cohabiting, many individuals say “it just happened” (Lindsay, 2000). Some have suggested that such a slide into cohabitation may put couples at risk for later distress because they lack a foundation of mutual commitment (see Stanley, Rhoades, & Markman, 2006). Thus, we are beginning to learn how cohabitation begins, but we know little about the psychology of cohabitation, that is, why couples begin cohabiting.

Examining reasons for cohabitation could shed light on the cohabitation effect, which refers to the finding that couples who cohabit premaritally are at greater risk for marital distress and divorce (Cohan & Kleinbaum, 2002; Kamp Dush, Cohan, & Amato, 2003; G. H. Kline et al., 2004; Stanley, Whitton, & Markman, 2004). Robust measurement of couples’ reasons for cohabiting could advance our understanding of which couples are most at risk of experiencing the cohabitation effect. For example, couples who cohabit because they have doubts about making a marriage work may be most at risk for later divorce, should they marry.

The present study used in-depth mail surveys of 120 couples to address a fundamental question in the cohabitation literature: what reasons do partners give for living together? Additionally, we examined within-couple gender differences in reasons for cohabitation and tested hypotheses about how reasons relate to personal (e.g., attachment, depressive symptoms), and relationship characteristics (e.g., communication, dedication).

Qualitative research shows that many cohabiting individuals give financial and convenience-related reasons for moving in together (Sassler, 2004), but a quantitative study from the 1987–88 wave of the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH) found that only a quarter of cohabiting individuals thought sharing living expenses was an important reason to live together outside of marriage (Bumpass et al., 1991). In that study, testing compatibility was the only reason that more than 50% of the sample endorsed as important. This previous quantitative research is limited in that it inquired about individuals’ beliefs about cohabitation in general, rather than reasons for cohabitation specific to their own relationships. Thus, it is difficult to draw conclusions about how one’s reasons for cohabitation might relate to relationship quality. Further, this research is now nearly 20 years old and the prevalence and meaning of cohabitation is changing quickly in the United States (Smock, 2000). Thus, the present study filled a wide gap in the literature on cohabitation by using a new, comprehensive measure of reasons for cohabitation that asked both partners specifically why they began living together and examined how their reasons related to relationship and personal characteristics.

The study of reasons people give for marrying provides a useful framework transitions into cohabitation. Surra and Hughes (1997) made a distinction between relationship-driven reasons for marriage (e.g., wanting to spend life together) versus event-driven reasons (e.g., pregnancy). In their work, event-driven reasons were associated with lower marital quality. This distinction fits with commitment theories that differentiate an intrinsic desire to maintain one’s relationship from constraining forces that increase the cost of leaving thereby encouraging relationship continuance (see Adams & Jones, 1997). In Stanley and Markman’s (1992) theory, the internally-based form of commitment is called dedication and the external form is referred to as constraint commitment. Theoretically, Surra and Hughes’ relationship-driven reasons are in line with dedication and event-driven reasons are similar to constraint commitment.

Commitment theory and previous research on why couples form cohabitations show that it is useful to distinguish internal from external reasons. We consider internal reasons for cohabitation those that are associated with positive attributes made about the partner or relationship. Specifically, we focus on internal reasons reflecting a desire to be together and to experience greater intimacy (e.g., “I moved in with my partner because I wanted to spend more time with him/her”). In contrast, external reasons could be thought of as reasons related to attributes about the situation (e.g., “I moved in with my partner because I could not afford rent on my own.”). The external reasons examined here concern convenience (e.g., “I moved in with my partner because it was inconvenient to have some of my stuff at my place and some at my partner’s”). We wished to develop items that could be measured on a continuum and that would apply to most cohabiting individuals, therefore we did not focus on any specific external reasons (e.g., “I moved in with my partner because I/my partner was pregnant”). Testing the relationship before marriage was a third possible reason for cohabitation and reflects some desire for a future together, but also some uncertainties. This reason for cohabiting seemed especially important to assess, given that many people believe cohabiting provides a good test and improves one’s chances in marriage (Bumpass et al., 1991; Johnson et al., 2002).

There were three goals for the present study. First, we sought to understand individuals’ reasons for cohabitation using a newly developed measure, the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale. A confirmatory factor analysis was used to test our hypothesis that the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale would yield three factors: time together, convenience, and testing. No other quantitative measures of reasons for cohabitation exist (to our knowledge), so to test construct validity this new scale was compared with a simple rank order measure of reasons for cohabitation that was included in the battery of questionnaires. We expected that high scores on time together would be associated with ranking “spend more time” highest, that high scores on convenience would be associated with ranking “ made most sense financially” highest, and that high scores on testing would be associated with ranking “test our relationship” highest. Second, we wished to examine whether individuals’ reasons for cohabitation were associated with individual characteristics and relationship quality. With regard to individual characteristics, we measured religiousness, relationship history (i.e., number of sexual and cohabiting partners), symptoms of depression and anxiety, and attachment insecurity (i.e., fears of closeness, anxiety about abandonment, and difficulty depending on others). We chose these particular dimensions because of their links with relationship outcomes in prior research (see Clements, Stanley, & Markman, 2004; Davila & Bradbury, 2001; Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochluk, 1997; G. H. Kline et al., 2004; Teachman, 2003) and because some research and theory suggests that such “selection” factors can explain the cohabitation effect (see Woods & Emery, 2002). Relationship quality included several indices, as well: global relationship adjustment, physical and psychological aggression, negativity of interactions, relationship confidence, and dedication. We hypothesized that reasons reflecting a desire for more time together would be related to higher levels of individual and couple functioning while convenience and testing-related reasons would be associated with lower levels of functioning in both domains. Third, we had data from both partners, so we examined the convergence of partners’ reasons for cohabitation to explore whether men and women would give similar reasons for wanting to live together. Specifically, we looked at within-couple gender differences on the time together, testing, and convenience subscales of the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale. We made no predictions about gender differences in reasons for cohabitation because, to our knowledge, previous literature on this subject does not exist.

Method

Participants

Participants were 120 heterosexual couples. The median length of cohabitation was just less than a year and a half (Mdn = 75.14 weeks, M = 100.47, SD = 104.08, Range =.71 to 492.14) and had been in their relationships for 173.08 weeks (slightly more than three years; SD = 112.06 weeks); 30 couples (25%) were engaged at the first wave of data collection. Women, on average, were 27.74 years old (SD = 5.69 years), had completed 16.46 (SD = 2.19) years of education (slightly more than a bachelor’s degree), and made $20,000–29,000 annually. The women in this sample were 82.5% White, 4.2% Asian, 4.2% Hispanic, .8% Black, and 4.1% other; 4.2% did not report their ethnicity. Men, on average, were 29.93 years old (SD = 6.93 years), had completed 16.13 (SD = 2.66) years of education (slightly more than a bachelor’s degree), and made $30,000–39,000 annually. The men in this sample were 89.2% White, .8 Asian, 5.0% Hispanic, .8% Black, and 1.7% other; 2.5% did not report their ethnicity. The vast majority of women (89.17%) and men (87.4%) had never been married; 9.16% of couples reported that they had children living in their homes.1 Couples were living in 26 different states, as well as St. Croix, Canada, and England (United States citizens living abroad).

Procedure

Brief recruitment announcements describing the study were sent to a variety of listservs and online announcement boards (e.g., www.craigslist.org in large U.S. areas and cities, Alternatives to Marriage Project, Smart Marriages), as well as various other online and printed communications (e.g., university alumni mailings, community center newsletters). This recruitment announcement invited interested individuals to visit a website that contained a brief description of the project and to contact the principle investigator directly. In part, snowball sampling was used in that the announcement also asked readers and participants to forward the information to people they knew who were cohabiting. Couples who expressed interest were mailed two sets of questionnaires (one for each partner). They were sent a cover letter that explicitly asked that partners not share answers while completing forms. Two postage-paid envelopes were included so that partners could mail their forms back separately. As compensation, individuals who returned packets were entered into a $50 lottery.

Response rates

Given the web-based recruitment methods, it is impossible to know how many qualified individuals learned about the study but did not express interest. During the six-month recruitment phase, 252 individuals expressed that they and their partners were interested in receiving packets. Of these 252 couples who were then mailed packets, two subsequently indicated on their forms that they were not living together and they were therefore dropped from the study, six couples returned their forms and indicated that they were in same-sex relationships (these data were not used in the present analyses), and two couples broke-up before they had a chance to complete the forms. Aside from the aforementioned couples, 172 women and 120 of their partners returned forms. There was one man who returned forms whose female partner did not. Given the focus on couples, individuals whose partners did not participate were dropped from this study’s analyses, leaving a final sample of 120 heterosexual couples.2

As part of the larger study, everyone who returned packets was sent another questionnaire packet approximately 6 months later. Of the 120 men and 120 women who completed the first assessment, 67 men and 84 women returned their second assessment forms. The average time between these assessments was 7.60 months (SD = 1.48, Mdn = 7.36, Range = 5.23 – 11.47 months). These data were used for test-retest analyses on the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale.3

Measures of Reasons for Cohabitation

Reasons for Cohabitation Scale

The Reasons for Cohabitation Scale was developed for this project (see Table 1). It asks participants how strongly they agree with 29 potential reasons for cohabitation (e.g., “I moved in my partner because I wanted a trial run for marriage”) on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) response scale. Items were developed based on consultations with colleagues and previous studies on entrance into cohabitation (Lindsay, 2000; Manning & Smock, 2005; Sassler, 2004). Items were written to measure the three major types of reasons discussed earlier (time together, convenience, and testing). The “convenience” subscale included 6 items that measure the degree to which an individual was cohabiting because it was convenient. The “testing” subscale included 13 items that measure a desire to test the relationship through cohabitation. The “time together” subscale included 10 items that measure the degree to which individuals are cohabiting out of an intrinsic desire to have more time and intimacy with a partner. Cronbach’s alphas (α) were calculated to measure internal consistency. For men, α(convenience subscale) =.72, α(testing subscale) =.92, and α(time together subscale) =.77. For women, α(convenience subscale) =.74, α(testing subscale) =.92, and α(time together subscale) =.76. Test-retest reliability over a 7.60 month period (on average) was .67 for convenience, .69 for time together, and .73 for the testing subscale. An additional 16 items that pertain to specific events or circumstances (e.g., pregnancy or fear of losing government assistance) have been written, but are not included in the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale because they would apply only to certain respondents. These items can be obtained from the first author.

Table 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale

| Item | Mean (SD) | Covariance Estimate | Standard Error of the Estimate | Standardized Estimate for Men | Standardized Estimate for Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I moved in with my partner… | |||||

| Time Together Subscale | |||||

| 1. because I love spending time with him/her. | 6.44 (.89) | Set to 1.00 | .63 | .63 | |

| 3. so that we could have more daily intimacy and sharing. | 5.84(1.25) | 1.52 | .18 | .63*** | .73*** |

| 7. because I knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life with him/her. | 5.03(1.84) | 1.51 | .24 | .45*** | .47*** |

| 18. because I wanted to spend more time with him/her. | 6.22(1.09) | 1.53 | .17 | .80*** | .76*** |

| 19. because I wanted us to have more privacy. | 4.19(2.17) | 1.40 | .29 | .37*** | .35*** |

| 25. to improve our sex life together. | 3.21(1.96) | 1.03 | .25 | .29*** | .31*** |

| 26. because it was emotionally hard to be apart. | 4.31(1.93) | 1.66 | .27 | .47*** | .48*** |

| 27. because I thought it would bring us closer together. | 4.71(1.74) | 1.06 | .23 | .33*** | .35*** |

| 28. because we didn’t have enough time together when we lived in separate places. | 4.61(1.93) | 1.89 | .26 | .56*** | .56*** |

| 29. because I want us to have a future together. | 5.83(1.38) | 1.33 | .19 | .56*** | .53*** |

| Testing Subscale | |||||

| 2. because I wanted to find out how much work he/she would do around the house before deciding about marriage. | 1.71(1.21) | Set to 1.00 | .39 | .42 | |

| 4. because I wanted to test out our relationship before deciding whether to marry him/her. | 3.47(1.99) | 3.59 | .57 | .89*** | .88*** |

| 5. because I had doubts about us making it for the long haul. | 2.15(1.50) | 1.96 | .34 | .64*** | .64*** |

| 6. because I wanted a trial run for marriage. | 2.49(1.77) | 2.73 | .45 | .74*** | .78*** |

| 8. because I want to make sure we are compatible before deciding about marriage. | 3.63(2.07) | 3.77 | .59 | .90*** | .89*** |

| 9. because I have concerns about our relationship and thought living together would be a good way to test out my concerns. | 2.04(1.45) | 2.04 | .34 | .64*** | .75*** |

| 10. because I had concerns about whether I wanted to be with my partner long-term. | 2.05(1.52) | 2.06 | .35 | .64*** | .70*** |

| 12. because it’s the only way we will know if we are ready to get married. | 2.99(1.93) | 3.23 | .52 | .82*** | .85*** |

| 13. because I was concerned that he/she might not make a good husband/wife and thought living together would be a good way to find out. | 1.87(1.33) | 1.64 | .29 | .59*** | .62*** |

| 14. to get to know him/her better before deciding about marriage. | 3.22(2.05) | 3.33 | .54 | .80*** | .80*** |

| 20. because I had doubts about how well I could handle being in a serious relationship. | 1.93(1.49) | 1.49 | .29 | .49*** | .48*** |

| 23. because I was concerned about how my partner handles money and wanted time to test out my concerns before marriage. | 1.69(1.19) | 1.27 | .24 | .49*** | .50*** |

| 24. because I wanted to make sure we would both contribute to running the household. | 2.45(1.75) | 1.81 | .34 | .49*** | .53*** |

| Convenience Subscale | |||||

| 11. to share household expenses. | 3.93(1.81) | Set to 1.00 | .77 | .85 | |

| 15. because we were spending most nights together anyway. | 5.05(1.88) | .27 | .09 | .22** | .20** |

| 16. because I could not afford rent on my own. | 1.79(1.46) | .39 | .07 | .46*** | .37*** |

| 17. because it was inconvenient to have some of my stuff at my place and some at my partners. | 2.70(1.94) | .43 | .09 | .35*** | .32*** |

| 21. because it was convenient. | 4.03(1.93) | .55 | .09 | .44*** | .41*** |

| 22. because it made sense financially. | 4.31(1.91) | 1.13 | .10 | .84*** | .92*** |

Notes. N = 120 couples.

p <.01,

p <.001. Paths were constrained across gender. For example, the loading for item 1 on the time together subscale for women was forced to be equal to the loading for item 7 on the time together subscale for men. Each item began with “I moved in with my partner…”

Rank-ordered reasons for cohabitation

As a measure of construct validity, participants were asked to rank order four options for why they started cohabiting: 1) I wanted to test out our relationship before marriage, 2) I wanted to spend more time with my partner, 3) It made the most sense financially, and 4) I don’t believe in the institution of marriage. This item was used primarily for testing construct validity of the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale.

Measures of Personal Characteristics

Demographics

Basic demographic information (e.g., age, ethnicity, education level) was collected on a form that also contained questions about the length of the current relationship, engagement status, number of prior cohabitations and sexual partners. A single item measure of religiousness was also included on this form: “All things considered, how religious would you say that you are?” The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very religious).

Depression and anxiety symptomatology

Twelve items from the well-validated Brief Symptom Inventory (see Derogatis, 1993) were used to assess symptoms of depression and anxiety. The measure instructed participants to indicate how often they experienced each item (e.g., “feeling lonely,” “feeling tense or keyed up”) in the past 30 days on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) scale. In the present study, αs for depression scores were .85 for men and .79 for women. For anxiety scores, α for men was .75, for women it was .57.

Attachment insecurity

The Adult Attachment Scale (Collins & Read, 1990) assessed dimensions of attachment. It is an 18-item measure with three subscales: Fear of closeness, which measures discomfort with closeness and intimacy; difficulty depending, which measures the extent to which people have trouble trusting others and depending on them to be available when needed; and abandonment anxiety, which assesses fears of being abandoned and not being loved. The Adult Attachment Scale has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity (Kurdek, 2002). In the present study, αs for men and women ranged from .59 to .87 (Mdn =.76, SD =.11). The abandonment anxiety subscale was the one with the lowest reliability.

Measures of Couple Characteristics

Global relationship adjustment

The brief, 7-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale is a widely used measure of global relationship adjustment with high reliability and validity (see Hunsley, Best, Lefebvre, & Vito, 2001; Spanier, 1976). Here, α for men was .74 and for women it was .71.

Psychological and physical aggression

Couples completed the 20 items from the Conflict Tactics Scale-II (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) that make up the psychological and physical aggression subscales. These subscales have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in previous research (Straus et al., 1996). In this sample, the αs for men were .77 for the psychological aggression subscale and .79 for the physical assault subscale; for women they were .82 and .69 respectively.

Negative interaction

The 8-item Communication Danger Signs Scale (Stanley & Markman, 1997) assessed dimensions of negative interaction, including escalation, invalidation, and withdrawal. An example item is: “My partner criticizes or belittles my opinions, feelings, or desires.” Respondents rate items on a 1 (almost never) to 3 (frequently) scale. In married and cohabiting couples, this measure has demonstrated high reliability and validity (G. H. Kline et al., 2004; Stanley et al., 2001). In the present study, the α for men and for women was .73.

Relationship confidence

The 10-item Confidence Scale (Stanley, Hoyer, & Trathen, 1994) was used to examine individuals’ sense of confidence in the quality and stability of their relationships. An example item is: “I believe we can handle whatever conflicts will arise in the future.” Respondents agreed or disagreed on a 7-point Likert scale. This measure has demonstrated high reliability and validity (Stanley et al., 2001); in particular, it discriminated between couples who cohabited prior to engagement versus only after engagement or marriage (e.g., G. H. Kline et al., 2004). In the present study, α for men and for women was .96.

Dedication

The 14-item dedication subscale of the Commitment Inventory (CI; Stanley & Markman, 1992) was used to assess dedication, also known as interpersonal commitment (i.e., an intrinsic desire to be with one’s partner into the future). The CI has demonstrated high levels of internal consistency and validity in previous research (e.g., Adams & Jones, 1997; Stanley & Markman, 1992). In the present study, α for men =.86, for women α =.87.

Results

Measure Development

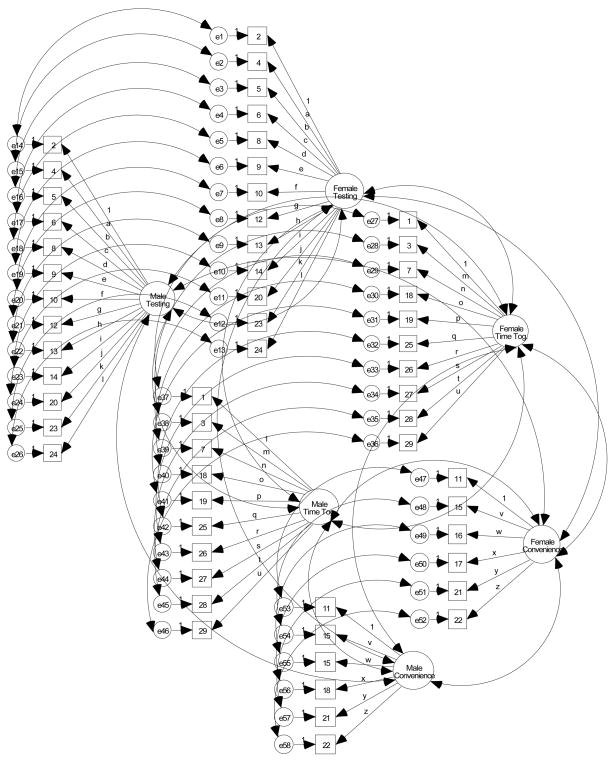

Amos 5.0 was used to conduct confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) on the factor structure of the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale. One subscale was hypothesized to measure a participant’s desire to test the relationship, one was hypothesized to measure reasons related to convenience, and one was hypothesized to measure reasons related to a desire for more time together and intimacy. For the CFA model (see Table 1 and Figure 1), both partners’ scores were entered into a single analysis and the factors were correlated across genders, as were the error terms for the individual items; these cross-gender correlations account for the dependency in the data. This model was recommended by Kenny, Kashy, and Cook (2006). Kenny et al. further suggest that all paths in the model (i.e., from items to their factors) be constrained (set equal) across gender. All three factors (subscales) were allowed to correlate with one another.

Figure 1.

Dyadic Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model for the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale

Note. The letters accompanying paths demonstrate the paths were constrained across partners.

Each lettered path was statistically significant (p <.01).

There was only a negligible amount of missing data on the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale. Out of 6960 possible data points (item level responses), 11 were missing (.16%). On nine items on the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale, between one and three participants did not provide an answer. No participants missed more than two items on the scale. For confirmatory factor analyses, the item’s mean was substituted for these missing data.

The results showed three independent factors; within both men and women, the testing, convenience, and time together factors were not significantly correlated with each other (rs ranged from −.18 to .06, p >.10). The magnitude of the correlations of error terms across men and women demonstrate a small overall level of dependency in the data (rs ranged from −.18 to .47, M =.16, SD =.18). The testing, convenience, and time together factors were correlated across men and women in predictable ways, rs =.50, .35, .28, respectively, ps <.05.

The model fit for the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale CFA was fair according to the Root Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA =.089) and χ2/df statistics (χ2/df = 1.94) (see Browne & Cudeck, 1993, R. B. Kline, 1998), but not according to the Comparative Fit Index (CFI =.63). Based on the factor loadings (Table 1), one might choose to drop item 15 (“I moved in with my partner because we were spending most nights together anyway”) from the convenience subscale because it did not load as strongly as the other items. Dropping item 15 did not affect the fit of the model in a meaningful way, so it was retrained.

To test for gender differences in the way items load on factors (subscales), we compared this model to one in which the paths were not constrained across gender. When paths were not constrained, the model fit indices indicated very similar fit to the constrained model, χ2(1551) = 3038.09, p <.001, χ2/df = 1.96, RMSEA =.091, CFI =.63. A χ2 difference test comparing the constrained and unconstrained models was non-significant, indicating the model in which paths from individual items to the corresponding subscales were constrained across gender did not fit significantly worse than the model in which these paths were free to vary. Thus, there was not a significant gender difference in the way items load on the factors.

As noted in the Method, Cronbach’s alphas (α) were calculated separately for men and women for each of the three subscales and indicated moderate to high reliability (Table 2). An examination of the alpha-if-item-deleted statistics indicated that there were no items on any of the subscales that, if removed, would have improved internal consistency. Commensurate with the correlations between factors presented above, correlations among the subscales were low, indicating that each subscale measures a different construct (Table 2).

Table 2.

Internal Consistency of and Correlations among Reasons for Cohabitation Subscales

| Men | Women | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Testing | Time Together | Convenience | Testing | Time Together | Convenience | ||

| Men | Testing | 2.58 | 1.20 | (.92) | |||||

| Time Together | 5.02 | 0.93 | .09 | (.77) | |||||

| Convenience | 3.54 | 1.09 | .13 | −.01 | (.72) | ||||

| Women | Testing | 2.34 | 1.17 | .45** | −.04 | −.05 | (.92) | ||

| Time Together | 5.06 | 0.96 | .19 | .28** | −.13 | .09 | (.76) | ||

| Convenience | 3.74 | 1.28 | −.05 | −.10 | .41** | .07 | −.14 | (.74) | |

Notes. p <.01.

N = 120 couples. Internal consistency (α) estimates for T1 data appear in the diagonals.

We also checked construct validity of the subscale scores by comparing the scores to the rank-order data that were collected. As was expected, a priori contrasts (two-tailed t-tests) showed that those who ranked I wanted to spend more time with my partner (M = 5.32, SD =.77) the highest had higher scores on the time together subscale than those that ranked I wanted to test out our relationship before marriage (M = 4.68, SD =.82, t(297) = 5.32, p <.001), it made the most sense financially (M = 4.37, SD =.96, t(308) = 8.21, p <.001), or I don’t believe in the institution of marriage first (M = 4.88, SD = 1.14, t(266) = 2.26, p <.05). Similarly, we found that those who ranked testing the relationship highest (M = 3.89, SD = 1.12) had higher scores on the testing subscale than those who ranked highest 1) spending more time together (M = 2.37, SD = 1.05, t(302) = 9.27, p <.001), 2) financial considerations (M = 2.77, SD = 1.23, t(108) = 4.96, p <.001), or 3) that they don’t believe in the institution of marriage (M = 1.51, SD =.74, t(66) = 8.33, p <.001). Likewise, those who ranked financial considerations highest (M = 4.43, SD = 1.19) had higher scores on the convenience subscale than those who ranked highest 1) spending more time together (M = 3.56, SD = 1.25, t(312) = 4.88, p <.001) or 2) testing the relationship (M = 3.47, SD =.95, t(108) = 4.64, p <.001). However, contrary to expectations, there was not a significant difference on convenience subscale between those who ranked financial considerations highest and those who ranked that they don’t believe in the institution of marriage highest (M = 3.94, SD = 1.32, t(76) = 1.51, p >.10).

Descriptive Information on Reasons for Cohabitation

Given the paucity of research on reasons for cohabitation, basic descriptive information is presented here on how participants characterized their reasons for cohabiting. As described above, there were three distinct subscales that were part of the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale measuring: 1) reasons for cohabitation related to a desire for more time together and greater intimacy (e.g., I moved in with my partner because I love spending time with him/her), 2) reasons related to convenience (e.g., I moved in with my partner because it was inconvenient to have some of my stuff at my place and some at my partners), and 3) reasons related to a desire to test one’s relationship (e.g., I moved in with my partner because I wanted a trial run for marriage). Scores on the subscales were calculated as means of the included items, and so could range from 1 to 7. Across all participants, most reported high levels of reasons related to time together (M = 5.03, SD =.94, Mdn = 5.10, Range = 1.60 to 7.00), moderate levels of cohabiting out of convenience (M = 3.60, SD = 1.20, Mdn = 3.50, Range = 1.00 to 6.50), and low levels of cohabiting to test the relationship (M = 2.46, SD = 1.19, Mdn = 2.31, Range = 1.00 to 6.00).

The rank-order measure of reasons for cohabitation provides additional descriptive information. Across all participants, 61.2% ranked I wanted to spend more time with my partner as their number one reason for moving in together while 18.5% ranked It made the most sense financially highest, 14.3% ranked I wanted to test out our relationship before marriage highest, and 6.0% ranked I don’t believe in the institution of marriage highest.

Associations among Reasons, Individual Characteristics, and Relationship Quality

We tested whether reasons for cohabitation were associated with individual characteristics and relationship quality with Pearson correlations (see Table 3). Few self-reported personal characteristics were significantly associated with cohabiting for more time together or for convenience. The exceptions were that higher levels of men’s religiousness were associated with lower scores for men on the time together subscale and higher levels of women’s religiousness were associated with lower convenience scores for women.

Table 3.

Correlations among Reasons for Cohabitation and Individual and Couple Characteristics

| Reasons for Cohabitation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men’s Reasons | Women’s Reasons | |||||

| Measure | Time Tog. | Testing | Conv. | Time Tog. | Testing | Conv. |

| Men’s Self-Reports of Personal Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Religiousness | −.19* | .03 | .09 | −.15 | .11 | .05 |

| Sexual Partners | −.07 | −.10 | −.02 | −.25** | −.15 | −.01 |

| Cohabiting Partners | .08 | −.08 | −.11 | −.01 | −.07 | −.11 |

| Depression Symptoms | .05 | .24** | .14 | .05 | .21* | .10 |

| Anxiety Symptoms | .12 | .18* | .01 | .03 | .05 | .05 |

| Fear of Closeness | −.05 | .15 | .03 | .03 | .14 | .05 |

| Difficulty Depending | −.03 | .23* | .06 | −.10 | .17 | −.08 |

| Abandonment Anxiety | .13 | .20* | .01 | −.12 | .12 | .16 |

|

| ||||||

| Men’s Self-Reports of Couple Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Negative Interaction | .07 | .49*** | .13 | .06 | .42*** | .11 |

| Psychological Aggression | −.04 | .23* | .13 | −.01 | .23* | .11 |

| Physical Aggression | .11 | .23* | .05 | .04 | −.13 | −.04 |

| Relationship Adjustment | .12 | −.38*** | −.11 | .02 | −.29** | −.12 |

| Relationship Confidence | .26** | −.33*** | −.16 | .15 | −.24** | −.13 |

| Dedication | .23* | −.36*** | −.14 | .05 | −.13 | −.12 |

|

| ||||||

| Women’s Self-Report of Personal Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Religiousness | .08 | .05 | −.14 | .04 | −.02 | −.23* |

| Sexual Partners | .01 | −.15 | −.18* | −.08 | −.17 | −.08 |

| Cohabiting Partners | .17 | −.22* | −.17 | −.06 | −.24** | .01 |

| Depression Symptoms | −.05 | .18* | .13 | .03 | .05 | .13 |

| Anxiety Symptoms | −.05 | −.01 | −.07 | .02 | −.01 | .08 |

| Fear of Closeness | .02 | .05 | .11 | −.13 | .15 | .10 |

| Difficulty Depending | .12 | .10 | .06 | .01 | .08 | .06 |

| Abandonment Anxiety | −.07 | .30** | −.09 | .11 | .27** | −.05 |

|

| ||||||

| Women’s Self-Report of Couple Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Negative Interaction | −.02 | .13 | .05 | −.04 | .28** | .10 |

| Psychological Aggression | .01 | .27** | .04 | .03 | .36*** | .21* |

| Physical Aggression | −.05 | .16 | .06 | −.01 | .07 | .06 |

| Relationship Adjustment | .11 | −.24** | .03 | −.01 | −.39*** | −.06 |

| Relationship Confidence | .15 | −.01 | −.12 | .37*** | −.26** | −.26** |

| Dedication | .05 | .07 | −.17 | .38*** | −.04 | −.31** |

Notes. Ns range from 112 to 120 for each correlation. Conv. = Convenience subscale.

In contrast, a number of self-reported personal characteristics were significantly associated with cohabiting to test the relationship. For men, higher levels of depressive symptoms, generalized anxiety symptoms, difficulty depending on others, and anxiety about abandonment were significantly associated with higher scores on testing. For women, having more previous cohabitation partners was significantly associated with lower scores on testing and greater abandonment anxiety was significantly associated with higher testing scores.

With regard to relationship quality, no variables were significantly correlated with cohabiting out of convenience for men. For women, lower levels of relationship confidence and dedication and higher levels of psychological aggression were significantly associated with convenience. Higher relationship confidence and dedication were significantly associated with the degree to which both men and women were cohabiting because they wanted more time or intimacy with their partners. For both men and women, greater negative interaction and psychological aggression and lower relationship confidence and adjustment were significantly associated with higher scores on the testing subscale. For men only, greater physical aggression and lower levels of dedication were significantly associated with testing the relationship.

It is also evident from Table 3 that there were cross-partner correlations in which partner’s self-report scores on a measure were associated with one’s own reasons for cohabitation (e.g., higher depressive symptomatology was significantly associated with higher partners’ testing scores for both men and women). These cross-partner associations seem most meaningful in the individual characteristics domain where the within-couple correlations (i.e., the correlations between men’s and women’s scores) tended to be lower (rs range from .14 for abandonment anxiety to .52 for number of sexual partners, Mdn =.25) than in the couple characteristics domain (rs range from .21 for dedication to .56 for psychological aggression, Mdn =.39). When a high within-couple correlation exists, it is less likely that one’s partner’s self-report score would explain unique variance in one’s own reasons for cohabitation.

Tests of Similarity between Partners

Because our data represented paired partners, comparisons between men and women reflect convergence between partners, rather than simple differences or similarities between men and women in general. Table 2 demonstrates that partners’ scores on the time together, convenience, and testing subscales were significantly correlated. The magnitudes of the correlations were small to medium, indicating modest agreement between partners for how strongly they endorsed each of the three reasons compared to other participants.

A different angle on similiarity is to consider whether partners chose the same reason on the rank-order item. In 53.4% of couples, partners ranked the same reason as first; 46.6% did not.

Yet another way to consider similarity is to test for mean differences. To test for mean differences between male and female partners in reasons for cohabitation, we used a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) in which gender was treated as a within-subjects independent variable (to control for dependency). The three Reasons for Cohabitation Scale subscales were included as dependent variables. The MANOVA indicated a significant main effect of gender, F(3, 113) = 3.42, p <.05. Follow-up t-tests comparing men and women revealed that men (M = 2.54, SD = 1.20) were significantly more likely than their female partners (M = 2.34, SD = 1.19) to report that they were cohabiting to test the relationship while women (M = 3.81, SD = 1.24) were significantly more likely than their male partners (M = 3.56, SD = 1.10) to report that they were cohabiting out of convenience. There were no significant differences between men (M = 5.03, SD =.94) and women (M = 5.06, SD =.96) on the time together subscale.

Discussion

This study was a comprehensive, quantitative examination of couples’ reasons for cohabiting and correlates of such reasons. It examined associations between types of reasons for cohabitation, relationship quality and individual well-being. Although generalizability is limited, the findings showed that this sample endorsed reasons for cohabitation that reflected a desire for more time together most strongly, followed next by convenience-based reasons, and then by testing the relationship. Few individuals reported cohabiting because they did not believe in the institution of marriage.

In comparing these descriptive findings to previous research, fewer people endorsed testing the relationship as a major reason for their own cohabitations than might have been expected based on Bumpass et al.’s (1991) finding that testing for compatibility was important to the majority of cohabiting individuals. The findings are somewhat difficult to compare, however, because the present sample is not representative and the measure used here was designed to assess participants’ reasons for their own relationships whereas participants in the NSFH were asked generally about why people would cohabit. Additionally, the aforementioned study was conducted in the late 1980s, and the acceptability and prevalence of cohabitation has increased since then, so reasons may also be different today. Further, national estimates suggest that cohabitations generally dissolve or become marriages within a year or two (Bumpass & Lu, 2000) and the cohabitations in the present study averaged nearly two years, so it may be that this sample overrepresented couples who are living together as a long term alternative to marriage and underrepresented those interested in testing their relationships. Clearly, a current, representative sample of couples would yield important information about why couples cohabit. The current study presents preliminary evidence that the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale provides a valid means of measuring reasons and that certain reasons for cohabitation are meaningfully linked with individual and couple functioning.

As described earlier, it may be useful to broadly distinguish external and internal reasons for cohabitation. Desiring more time together could be considered an internal reason whereas convenience could be considered an external one. This distinction ties into commitment theory (e.g., Stanley & Markman, 1992) and also with Surra and Hughes’ (1997) research on event vs. relationship-driven reasons for marriage. Additionally, it may be that reasons that individuals give for cohabiting are linked with larger constructs, such as the classic distinction between internal versus external locus of control (Rotter & Mulry, 1965), that could help us better understand the factors and characteristics that encourage cohabitation. In future research, it may be important to examine other reasons for cohabitation, as well, especially external ones such as pregnancy, financial hardship, child care needs, or having no legal option to marry that would influence some individuals and populations more than others. The problem researchers face is that these possible reasons are not captured well in subscales because they represent specific and somewhat rare circumstances in the general population. The scales developed in this study were designed instead to be broad and applicable to the majority of cohabiting individuals.

Although it was not generally the primary reason for cohabiting, the degree to which individuals reported cohabiting as a means of testing their relationships was related to both individual well-being and relationship quality. With regard to individual well-being, testing was more likely among those reporting greater depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as attachment-related concerns (difficulties depending on others and anxiety about abandonment). Future longitudinal research on reasons for cohabitation and individual well-being could yield evidence for the direction of effects. For example, feeling depressed may lead to doubts about one’s relationship, leading one to want to test the relationship. On the other hand, low relationship quality could lead to both a desire test the relationship and feelings of depression. The notion that cohabitation could lead to higher levels of depression has some support in the field; Brown (2000) found that cohabiting individuals reported more symptoms of depression than did married individuals and that part of this difference was attributable to the higher level relationship instability experienced during cohabitation. Our findings more broadly suggest that mental health and patterns of insecure attachment are associated with testing as a motivation for cohabitation, though this finding now awaits replication in other samples.

Women with more prior cohabitation partners were less likely to report testing. This association could reflect that those with prior cohabitation experiences are less likely to believe in the institution of marriage. They would therefore not be seeking a relationship test before marriage. Follow-up analyses conducted with this data set provide some support for this assumption, as they suggested that for women, not believing in marriage was associated with more cohabitation partners (analyses available from the first author). In future research with a larger sample, it may be important to further distinguish cohabiting individuals who do not believe in marriage from those who do. There has not been much attention paid to cohabitations that serve as long term alternatives to marriage in the literature.

In addition to individual vulnerabilities, relationship characteristics associated with greater risk (e.g., negative interactions, physical aggression) were also associated with testing one’s relationship through cohabitation. Although causality cannot be demonstrated here, the findings are consistent with the notion that some individuals and/or couples may recognize their difficulties and seek cohabitation as a means for testing the relationship before marriage.

Few significant associations were found between couple or individual functioning and cohabiting to have more time together or out of convenience. For women, religiousness was associated with being less likely to cohabit out of convenience, but for men, religiousness was associated with lower scores on the time together subscale. Although religiousness is generally associated with whether or not couples choose to cohabit, there is no precedent we know of for understanding how religiousness relates to reasons for cohabitation within a sample of couples who are already cohabiting. Correlations also suggested that those who are committed to a future together (more dedicated) and who are confident in their relationships are more likely to report that they moved into together because they desire more time and intimacy together. Interestingly, reasons related to spending more time were not significant associated with general relationship adjustment, indicating that this subscale is not simply a proxy for the quality of a relationship.

Although we believe our measurement of reasons for cohabitation was strong, and associations with rank-ordered reasons provide evidence of construct validity, it could be that deficiencies in measurement account for the lack of association. Of the three subscales of the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale, the testing subscale had the strongest psychometric properties in terms of internal consistency and test-retest reliability. The less robust psychometric properties associated with the convenience and time together subscales could, in part, account for the lack of significant associations between these subscales and other variables. However, it also seems possible that cohabiting to test one’s relationship is simply more diagnostic of individual or relationship problems.

For about half the couples, partners had the same primary reason for cohabitation on the rank-order item and correlations indicated moderate similarity in the degree to which partners endorsed cohabiting to have more time together, to test the relationship, or out of convenience. For example, the more the male partner reported cohabiting to test the relationship, the more his female partner reported cohabiting to test the relationship. At the same time, there were, on average, mean differences between male and female partners on these subscales. Men were more likely than their partners to report cohabiting as a way to test their relationships and women were more likely than their partners to report cohabiting out of convenience. Future research should attempt to add to the knowledge base of why and for which couples differences in reasons for cohabitation occur, as well as elucidating the implications of the differences. Couples in which a large discrepancy exists could be most at risk for later problems in their marriages (if they marry) because they may have fundamentally different narratives for how and why they started cohabiting. The correlations among partners’ scores also make it complicated to interpret the degree to which one partner’s reasons for cohabitation may be related to the other’s report of relationship or personal characteristics. Actor-Partner Interdependence Models (see Kenny et al., 2006) may be useful in research targeting such questions.

Although the present study provides new information regarding reasons for cohabitation, generalizability is limited because the sample was a convenience sample. The present study represents the first foray into the area of quantitatively measuring individuals’ own reasons for cohabitation and examining correlates of various reasons; obtaining a random sample of cohabiting of couples is likely the next step in this line of research as it would provide important data about the broader experience of cohabitation. The recruitment strategies and the inclusion criteria for the present study (i.e., both partners needed to provide data) may mean that this study was selective of more committed cohabiting couples than would be found in the general population of cohabiting couples. The sample in the present study was also limited in that it was too small to examine differences across race, ethnicity, or income. Because there is some evidence that the experience of cohabitation differs by ethnicity (Phillips & Sweeney, 2005), it will be important to replicate these findings of with larger, more diverse samples. Additionally, there is accumulating evidence that couples’ marital intentions during cohabitation may help explain why cohabitation is linked with later risk for divorce (Brown & Booth, 1996; G. H. Kline et al., 2004; Stanley et al., 2006) and future longer term research could explore the links between marital intentions and reasons for cohabitation and their possible impacts on later marital quality.

There were also potential limitations related to measurement. First, the single-item religiousness scale may have limited the chances of finding significant associations between religiousness and reasons for cohabitation. Second, measurement of reasons for cohabitation occurred two years after couples began cohabiting, on average. We presented evidence of test-retest reliability over an eight-month period, but it is possible that individuals’ perceptions of why they started living together change over longer periods of time. It may be important to measure reasons nearer the time that cohabitation begins in future studies. Lastly, the fit statistics, internal consistency, and test-retest estimates indicated only fair reliability for the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale, though the current study’s findings should not prohibit the use of this scale in its current form in future research. Fit statistics are affected by the number of variables and parameters (Kenny & McCoach, 2003) and it could be that the typical guidelines for fit statistics are less applicable in complicated confirmatory factor analyses such as the one presented here. Alternatively, there may be ways to improve the fit of the model by trimming some items or reconsidering the make up of the subscales. It was not obvious from the results in the current study what modifications would strengthen the model. It may be that the psychometrics would be stronger in a larger, more heterogeneous sample.

With these limitations in mind, the present study provided novel information regarding the reasons couples give for living together and how their reasons are associated with the quality of their relationships and with individual well-being. The findings suggest important implications for individuals considering cohabitation and for relationship education programs seeking to educate individuals about cohabitation. If a desire to test one’s relationship is reflective of significant personal or relationship problems, it may important to help couples address the underlying issues before they begin cohabiting, especially because the dissolution of cohabiting unions has negative consequences, at least economically and especially for women (Avellar & Smock, 2005). More generally, given that many couples slide into cohabitation (Manning & Smock, 2005), it may be helpful to encourage partners to discuss their reasons for wanting to live together and to make sure that their expectations about the future of their relationships are clearly understood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD047564-01A2).

Footnotes

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) indicated that those with children in the home reported more reasons related to desiring more time together and intimacy (M = 5.63, SD =.85) than those without (M = 4.98, SD =.94), F(1, 114) = 8.23, p <.01, but there were no significant differences on the testing or convenience subscales. There is no reason to believe that the factor structure of the Reasons for Cohabitation Scale would be different or that reasons for cohabitation would be differentially associated with relationship or personal characteristics for those with children, so, they were retained in the current study to increase its generalizability.

ANOVAs indicated that women whose partners participated (and who were therefore included in the present study; M = 2.78, SD =.89) endorsed significantly fewer convenience-related reasons for cohabitation than women whose partners did not participate (M = 3.29, SD =.99), F(1, 170) = 10.98, p <.01. Thus, the mean convenience subscale score presented for women in the current study may not generalize to women whose partners are unwilling to participate in research on cohabitation.

ANOVAs showed that men who completed the second assessment (M = 3.31, SD = 1.12) were significantly less likely to endorse convenience as a reason for cohabitation (at the initial assessment) than men who did not complete the second assessment (M = 3.82, SD =.98), F(1, 118) = 6.73, p <.01. Women who completed the second assessment (M = 5.25, SD =.82) were significantly more likely to endorse reasons related to spending more time together than women who did not complete the second assessment (M = 4.65, SD = 1.11), F(1, 116) = 10.92, p <.01. There were no other significant differences in reasons for cohabitation. The only analyses based on the second wave of data collection are the test-retest analyses and it is unlikely that attrition would have affected those estimates dramatically.

References

- Adams JM, Jones WH. The conceptualization of marital commitment: An integrative analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72(5):1177–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Avellar S, Smock PJ. The economic consequences of the dissolution of cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:315–327. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, Thornton A. The relationship between cohabitation and divorce: Selectivity or causality? Demography. 1992;29(3):357–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Booth A. Cohabitation versus marriage: A comparison of relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1996;58(3):668–678. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation model. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Lu HH. Trends in cohabitation and implications for children s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies. 2000;54(1):29–41. doi: 10.1080/713779060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Sweet JA, Cherlin A. The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53(4):913–927. [Google Scholar]

- Clements ML, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Before they said “I do”: Discriminating among marital outcomes over 13 years based on premarital data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:613–626. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan CL, Kleinbaum S. Toward a greater understanding of the cohabitation effect: Premarital cohabitation and marital communication. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(1):180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(4):644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Bradbury TN. Attachment insecurity and the distinction between unhappy spouses who do and do not divorce. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(3):371–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Bradbury TN, Cohan CL, Tochluk S. Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: Evidence for a stress generation model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(4):849–861. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. 4. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, Best M, Lefebvre M, Vito D. The seven-item short form of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Further evidence for construct validity. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;29(4):325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, Stanley SM, Glenn ND, Amato PR, Nock SL, Markman HJ, et al. Marriage in Oklahoma: 2001 baseline statewide survey on marriage and divorce (S02096 OKDHS) Oklahoma City, OK: Oklahoma Department of Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush CM, Cohan CL, Amato PR. The relationship between cohabitation and marital quality and stability: Change across cohorts? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65(3):539–549. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy D, Cook W. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, McCoach DB. Effects of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10(3):333–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kline GH, Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Olmos-Gallo PA, St Peters M, Whitton SW, et al. Timing Is everything: Pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk for poor marital outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(2):311–318. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. On being insecure about the assessment of attachment styles. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships. 2002;19(6):811–834. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay JM. An ambiguous commitment: Moving into a cohabiting relationship. Journal of Family Studies. 2000;6(1):120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ. Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, Sweeney MM. Premarital cohabitation and marital disruption among white, black, and Mexican American women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter JB, Mulry RC. Internal versus external control of reinforcement and decision time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1965;2(4):598–604. doi: 10.1037/h0022473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S. The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(2):491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ. Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1976;38(1):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Hoyer L, Trathen DW. The Confidence Scale. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1994. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ. Sliding vs. deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations. 2006;55:499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Marriage in the 90s: A nationwide random phone survey. Denver, CO: PREP; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Prado LM, Olmos-Gallo PA, Tonelli L, St Peters M, et al. Community-based premarital prevention: Clergy and lay leaders on the front lines. Family Relations. 2001;50(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Whitton SW, Markman HJ. Maybe I do: Interpersonal commitment and premarital or nonmarital cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25(4):496–519. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283. [Google Scholar]

- Surra CA, Hughes DK. Commitment processes in accounts of the development of premarital relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman J. Premarital sex, premarital cohabitation and the risk of subsequent marital dissolution among women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65(2):444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Woods LN, Emery RE. The cohabitation effects on divorce: Causation or selection? Journal of Divorce and Remarriage. 2002;37(3–4):101–119. [Google Scholar]