Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS

A number of diseases are characterized by defective formation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. In the embryo, hepatoblasts differentiate to cholangiocytes which give rise to the intrahepatic bile ducts. Here we investigated how these ducts develop in mouse liver and characterized the role of the transcription factor SOX9.

METHODS

We identified SOX9 as a new biliary marker and used it with other cell markers in immunostaining experiments to characterize the process of bile duct morphogenesis. The expression of growth factors was determined by in situ hybridization and immunostaining, and their role was studied on cultured embryonic hepatoblasts. SOX9 function was investigated by phenotyping mice with a liver-specific inactivation of Sox9.

RESULTS

Biliary tubulogenesis started with formation of asymmetrical ductal structures, lined on the portal side by cholangiocytes and on the parenchymal side by hepatoblasts. When the ducts grew from the hilum to the periphery, the hepatoblasts lining the asymmetrical structures differentiated to cholangiocytes, thereby allowing formation of symmetrical ducts lined only by cholangiocytes. We also provide evidence that TGFβ promotes differentiation of the hepatoblasts lining the asymmetrical structures. In the absence of SOX9, the maturation of asymmetrical structures into symmetrical ducts was delayed. This was associated with abnormal expression of C/EBPα and HES1, as well as of the TGFβ receptor type II, which are regulators of biliary development.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that biliary development proceeds according to a new mode of tubulogenesis characterized by transient asymmetry and whose timing is controlled by SOX9.

INTRODUCTION

Several cases of neonatal cholestasis result from abnormal development of intrahepatic bile ducts1, hence the need to characterize the regulators of duct formation in the embryo. During liver development the hepatoblasts differentiate to hepatocytes or to biliary cells. The hepatocytes constitute cords associated with sinusoids, and biliary cells delineate bile ducts located close to the branches of the portal vein2,3. Bile duct morphogenesis starts in embryonic liver with the alignment of biliary cells around the branches of the portal vein to constitute a single-layered ring called ductal plate. Then, focal areas of the ductal plate become bilayered and form luminal structures which progressively give rise to bile ducts. In the perinatal period the bile ducts become surrounded by the periportal mesenchyme4–7.

Several transcription factors regulate biliary morphogenesis. In the absence of Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor (HNF) 6 and Onecut 2, the ductal plate gives rise to cysts rather than ducts8,9. Both factors modulate a periportal Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGFβ) signaling gradient, whose slope determines biliary development in the vicinity of the portal vein9. The Hematopoietically expressed homeobox factor factor (Hex) is located upstream of HNF6 in the liver transcriptional network10, and CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein α (C/EBPα), a factor expressed in hepatoblasts and hepatocytes, must be suppressed in biliary cells to allow expression of HNF6 and HNF1β11. The latter is a direct target of HNF6, and is also required for duct morphogenesis12. β-catenin, a mediator of Wnt signaling, also stimulates duct morphogenesis13,14. The factors mentioned above play a role in duct morphogenesis, but also in differentiation of hepatoblasts to biliary cells. Therefore, it is not clear whether the aberrant ductal morphogenesis seen in the corresponding knockout mice results from a role of the factors in duct formation or is a secondary consequence of abnormal biliary differentiation, or both. In contrast, the Homolog of Hairy/Enhancer of Split-1 (HES1), does not play a role in biliary differentiation, but is required for duct morphogenesis. In its absence in knockout mice the ductal plate forms but fails to give rise to tubular structures15. Importantly, HES1 is a mediator of Notch signaling and other components of this pathway were recently shown to control biliary tubulogenesis16,17.

The timing of expression of differentiation markers during bile duct morphogenesis has not yet been considered in detail. In this paper we provide an in-depth description of duct morphogenesis. We propose that it occurs according to a new mode of tubulogenesis that involves formation of asymmetrical ductal structures which are precursors of mature symmetrical ducts. We also address the role of the SRY-related HMG box transcription factor 9 (SOX9) in bile duct development. This factor plays a role in several progenitor cell types including those of the intestinal epithelium18,19 and pancreas20. It is also required for chondrocyte differentiation and sex determination: heterozygous mutations in humans are associated with XY sex reversal and campomelic dysplasia (OMIM #114290). The recent finding that SOX9 is expressed in pancreatic ducts20 prompted us to investigate its expression and function in bile duct development. We show here that SOX9 controls bile duct morphogenesis by regulating the maturation of the asymmetrical ductal structures into symmetrical bile ducts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Sox9-loxP (kindly provided by G. Scherer), Albumin/α-fetoprotein-Cre (Alfp-Cre), and Hnf6 knockout mice have been described21–23. Experimental protocols were approved by the local Animal Welfare Committee.

Immunofluorescence

Embryos were fixed at 4°C for 4h in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed overnight in PBS and embedded in paraffin. Immunofluorescence on 9 μm sections was as described24 using the antibodies as indicated in Supplementary Table I. Immunodetection of HES1 was carried out with Tyramide Signal Amplification kit (Molecular Probes). Anti-Hex antibodies were kindly provided by C. Bogue.

In situ hybridization

Embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in ethanol 60%, formaldehyde 30% and acetic acid 10%, paraffin embedded and sectioned (16 μm). Digoxygenin-labeled antisense RNA probes for TGFβ ligands and OPN were prepared by in vitro transcription of plasmids kindly provided by H.L. Moses and B. Sosa-Pineda. Antidigoxygenin antibody (Roche) coupled to alkaline phosphatase was diluted at 1:1500. Labeling was detected with 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (Roche) and sections were counterstained with aqueous eosin 1% (w/v).

Real-time quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

This was performed as described25. Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table II. For quantification of Osteopontin, Sox9, Hnf4, and TGF-beta receptor II, absolute copy number for each mRNA was normalized to absolute β-actin mRNA copy number, using standard calibration curves. Quantification of Transthyretin, Albumin and Notch2 mRNA was normalized to β-actin mRNA using the Δct method. Quantification of Jagged mRNA expression was also normalized to β-actin mRNA, but using the Pfaffl method.

Cell culture and transfections

BMEL cells were described, cultured and analyzed as described26. BMEL cells treated with TGFβ were cultured for 24h in medium with 0.1% fetal bovine serum before addition of TGFβ as indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Transient asymmetry during bile duct development

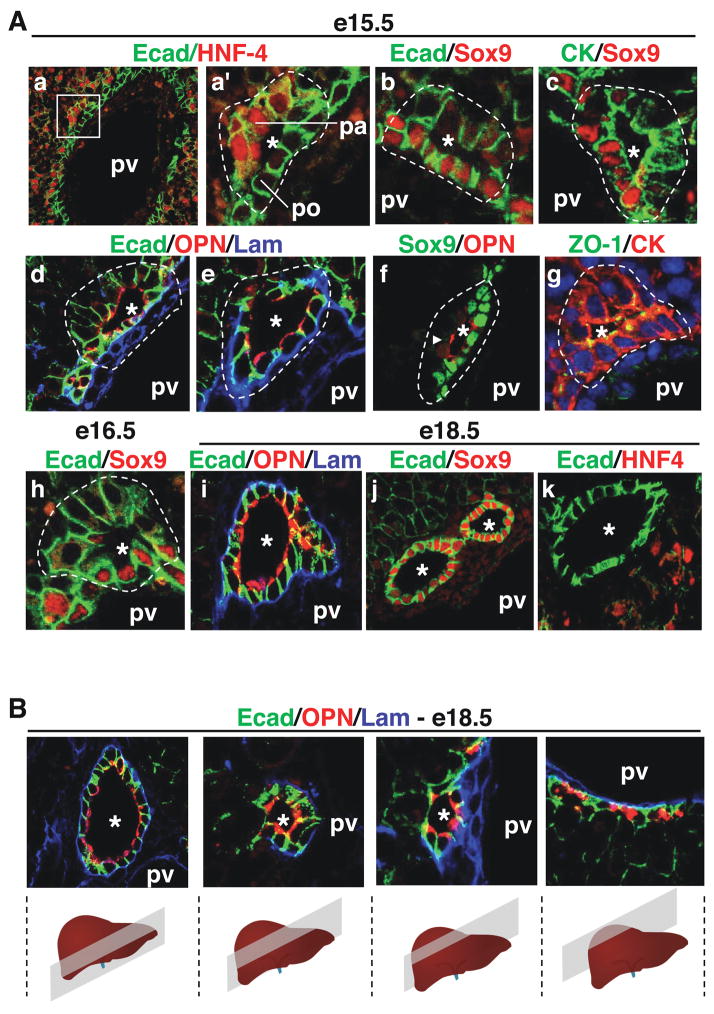

We first analysed the sequential steps of bile duct morphogenesis and looked at the expression of differentiation markers. At e15.5, when the ductal plate became focally bilayered, lumens were detected between the two layers, thereby forming primitive ductal structures (PDS). These PDS were asymmetrical. Indeed, as shown in Figure 1A (a, a′), the cells on the parenchymal side of the PDS, but not those on their portal side, stained for the hepatoblast marker HNF4. Furthermore, SOX9, which we found to be a new biliary marker (see Figure 4), was expressed on the portal but not on the parenchymal side of the PDS at e15.5 and e16.5 (Figure 1A; b, c, f, h). Also, at e15.5–e16.5 E-cadherin expression was higher on the portal side than on the parenchymal side. Laminin was initially detected only near the basal pole of the cells on the portal side, but then it progressively encircled the developing PDS (Figure 1A; d, e). Osteopontin (OPN), another new marker for embryonic biliary structures, was found early during formation of the single-layered ductal plate (Supplementary Figure 1) and at the apical pole of all PDS cells, while ZO-1 was detected at the tight junctions of the PDS cells (Figure 1A; d, e, g). This indicated that apical pole became established as soon as the lumens of the PDS were detectable.

Figure 1.

Development of bile ducts. (A) Immunostaining analysis showed that bile duct development is initiated by the formation of asymmetrical primitive ductal structures (PDS). a′ is a magnified view of the region delineated in a. By the end of gestation, bile ducts had become radially symmetrical (i–k). (B) Serial sections shows the hilum-to-periphery development of bile ducts, with symmetrical ducts near the hilum and asymmetrical PDS towards the periphery. The position of the portal vein relative to the bile ducts is indicated (pv). pa, parenchymal side of PDS; po, portal side; *, lumens of developing bile ducts.

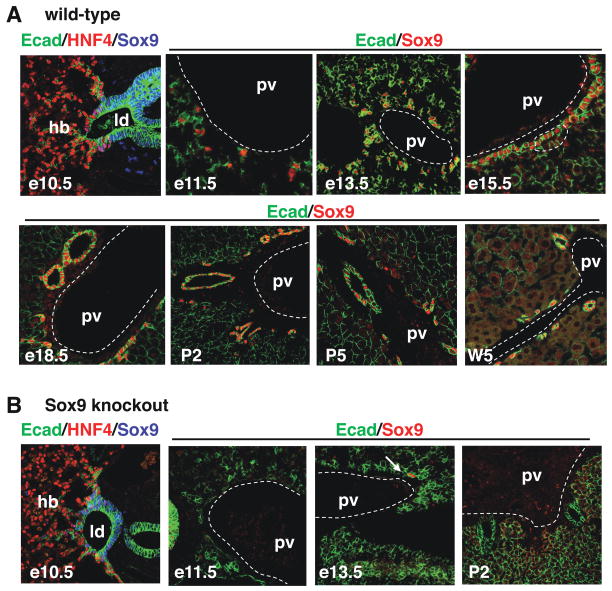

Figure 4.

Expression of SOX9 in wild-type livers and in livers with conditional inactivation of Sox9 alleles. (A) Expression profiling by immunostaining showed that SOX9 is an early and specific marker of the developing bile ducts. (B) In Alfp-Cre-Sox9loxP/loxP (Sox9 knockout) embryos, the livers were depleted of SOX9 starting at e11.5, except for one individual showing residual SOX9+ cells at e13.5 (arrow). hb, hepatoblasts; ld, liver diverticulum; pv, portal vein.

By the end of gestation, the non-tubular parts of the ductal plate involuted, the ducts developed from the PDS and displayed radial symmetry. Indeed, at e18.5 the bile ducts were delineated by a continuous layer of laminin, the duct cells were all SOX9-positive and HNF4-negative, and E-cadherin was equally expressed in all duct cells (Figure 1A; i–k). From these data we concluded that bile duct development occurs via a mode of tubulogenesis characterized by transient asymmetry. Moreover, we suggest that this asymmetry results from the apposition of hepatoblasts (parenchymal side) to biliary cells of the ductal plate (portal side), and that symmetry in mature ducts is reached when all PDS cells have acquired biliary characteristics.

Since it is known that bile duct development progresses from the hilum to the periphery of the liver lobes5, we expected that by the end of gestation symmetrical ducts would be found near the hilum, and asymmetrical PDS near the periphery of the lobes. This was the case. Indeed, serial sections of livers at e18.5 showed ducts with radially symmetrical distribution of laminin, OPN and E-cadherin near the hilum, and PDS with asymmetrical distribution of these markers towards the periphery (Figure 1B). Therefore, we propose that cells lining the parenchymal side of the PDS acquire biliary characteristics during development of the ducts along the hilum-periphery axis.

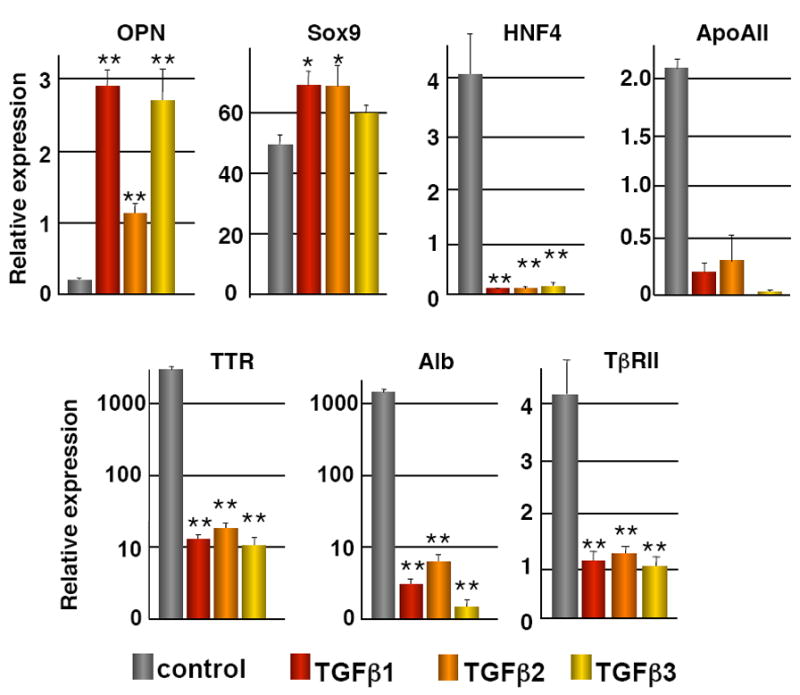

Asymmetrical TGF β signaling in primitive ductal structures

Our earlier work has shown that blocking TGFβ signaling in the liver represses differentiation of the single-layered ductal plate cells, and that stimulation of e12.5 liver explants with TGFβ induces biliary markers9. The mode of tubulogenesis described above suggests that HNF4-positive hepatoblasts on the parenchymal side of the PDS differentiate to HNF4-negative biliary cells during bile duct morphogenesis. To investigate if TGFβ can induce biliary marker expression and repress hepatocyte marker expression, we cultured hepatoblasts derived from e14.5 livers (BMEL cell line26) in the presence of TGFβ1, TGFβ2 or TGFβ3. As shown in Figure 2, the three ligands induced the biliary markers OPN and SOX9 and repressed expression of HNF4, albumin, apolipoprotein AII and transthyretin. The stimulation of SOX9 expression was modest as compared to that of OPN, most likely because the cells already expressed SOX9 under basal culture conditions. The latter interpretation was supported by the fact that a 12- and 16.5-fold stimulation of SOX9 was obtained by incubating liver explants with TGFβ2 or TGFβ3 (not shown).

Figure 2.

TGFβ signaling and development of bile ducts. Hepatoblasts (BMEL cells) were cultured in the presence or absence of TGFβ1, TGFβ2, or TGFβ3 (200 pg/ml). The expression (measured by Q-PCR) of the hepatocyte markers HNF4, Albumin (Alb), Transthyretin (TTR), Apolipoprotein AII (ApoAII) and TβRII was downregulated, and that of the biliary markers Osteopontin (OPN) and Sox9 was upregulated. Cells were treated for 24h (HNF4, ApoAII, Alb, TTR, TβRII, OPN) or for 6h (Sox9) with the TGFβ ligands. Data are means ± SEM; n ≥ 3; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Quantification was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section.

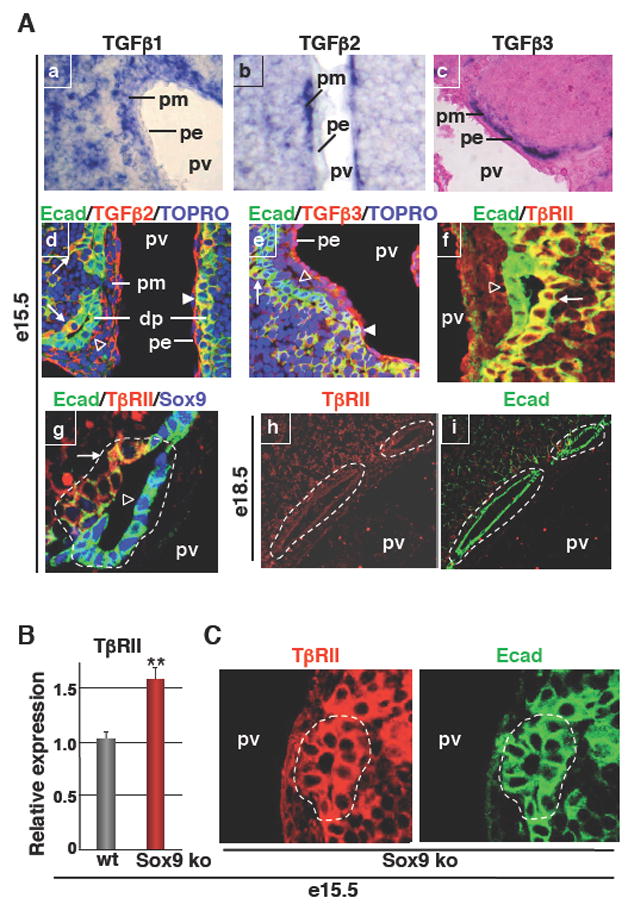

To differentiate HNF4-positive PDS cells to HNF4-negative biliary cells in vivo, TGFβ ligands should be expressed near the PDS and bind to the PDS cells. In situ hybridization on e15.5 sections showed that TGFβ1 mRNA was expressed widely in the liver. In contrast, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 mRNAs were found predominantly in the periportal mesenchyme, adjacent to the ductal plate (Figure 3A;a–c). Moreover, immunostaining to detect TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 proteins revealed that both ligands bind to the single-layered ductal plate cells (arrowheads in Figure 3A; d–e). In the PDS, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 were detected only on the parenchymal side (arrows in Figure 3A; d–e) and not on the portal side (open arrowheads in Figure 3A; d–e). These data indicated that a periportal source of TGFβ ligands is present in the liver when PDS are formed, and that PDS cells display asymmetrical binding of TGFβ ligands.

Figure 3.

TGFβ signaling and development of bile ducts in wild-type and SOX9-deficient livers. (A) In situ hybridization showing wide expression of TGFβ1 in the liver, while TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 mRNAs were predominantly found in the portal mesenchyme (a–c). Immunostaining showed binding of TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 to the parenchymal side of PDS (d, e). Immunostaining showing expression of TβRII on the parenchymal side of PDS and lack of expression in mature ducts (f–i). Arrows: TGFβ2, TGFβ3 or TβRII staining on parenchymal side of PDS; Arrowheads: TGFβ2 or TGFβ3 staining on single-layered ductal plate; open arrowheads: lack of TGFβ2, TGFβ3 or TβrII staining on portal side of PDS. (B) Q-PCR showing overexpression of TβRII in e15.5 Alfp-Cre-Sox9loxP/loxP (Sox9 ko) livers. (C) Immunostainings showed that primitive ductal structures detected by E-cadherin (E-cad) labeling expressed TβRII on both the portal side and parenchymal side in Alfp-Cre-Sox9loxP/loxP livers, in contrast to wild-type primitive ductal structures which express TβRII only on the parenchymal side (see panels Af, g). dp, single-layered ductal plate; pe, portal endothelium; pm, portal mesenchyme; pv, portal vein; *, lumens of developing bile ducts.

To explain why binding of TGFβ ligands to the PDS was restricted to the parenchymal side, we postulated that the TGFβ receptor type II (TβRII) could be present only on the parenchymal side of the PDS. This was verified by immunostaining. TβRII was indeed detected on the parenchymal side (arrows in Figure 3A; f–g) but not on the portal side of the PDS (open arrowheads in Figure 3A; f–g).

At later stages of development, TβRII was absent from the bile ducts (Figure 3A; h–i), suggesting that TβRII is repressed during biliary differentiation. To test if TGFβ can repress its own receptor we incubated hepatoblasts with TGFβ1, TGFβ2 or TGFβ3. As shown in Figure 2, the three ligands induced downregulation of TβRII in the hepatoblasts, and this was parallel with the abovementioned increase in biliary markers and repression of hepatocyte markers.

We concluded that the expression of TGFβ signaling components further supports the notion that bile duct morphogenesis involves transient asymmetrical structures. Also, the ex vivo effects of TGFβ on hepatoblasts, and on our earlier in vivo data on the role of TGFβ in biliary differentiation, lead to the suggestion that TGFβ promotes biliary differentiation of hepatoblasts and induces repression of TβRII. These events may occur successively on the two sides of the PDS to contribute to maturation of PDS into ducts.

Biliary-specific expression of SOX9 in developing liver

The asymmetrical expression of SOX9 in the PDS (Figure 1) and its stimulation by TGFβ (Figure 2) prompted us to consider this transcription factor as a candidate regulator of bile duct morphogenesis. We first looked in detail at its expression profile. SOX9 was detected at e10.5 in the endodermal cells lining the liver diverticulum, and was undetectable in the hepatoblasts invading the septum transversum (Figure 4A). At e11.5–e13.5, SOX9+ cells aligned around the portal vein to form a single-layered ductal plate. Later, SOX9 was expressed on the portal side of the PDS (e15.5) and then (e18.5) in all biliary cells until birth. After birth SOX9 expression regressed in large ducts but persisted in small ducts (P2, P5, W5). To our knowledge, these data showed that SOX9 is the most specific and earliest marker of biliary cells in developing liver.

SOX9 controls maturation of primitive ductal structures

To investigate the role of SOX9 in biliary development, we resorted to a conditional knockout approach in which loxP-flanked Sox9 alleles21 were inactivated by Alfp-Cre-mediated recombination22. Alfp-Cre is functional in hepatoblasts starting at e10.522. This is earlier than the onset of biliary development which we showed above to start around e11.5. Consequently, Alfp-Cre-mediated recombination allows to study gene functions in the developing intrahepatic biliary tract by a knockout strategy12. In all cases, biliary development was analysed near the hilum, and Sox9loxP/loxP- Alfp-Cre embryos were compared to littermate controls. The efficiency of inactivation was tested by immunostaining of livers from Sox9loxP/loxP- Alfp-Cre embryos. At e10.5 SOX9 is still detected in the endoderm cells, but efficient depletion of SOX9 was obtained starting at e11.5; in only one individual a few SOX9-positive cells were still found at e13.5 (Figure 4B).

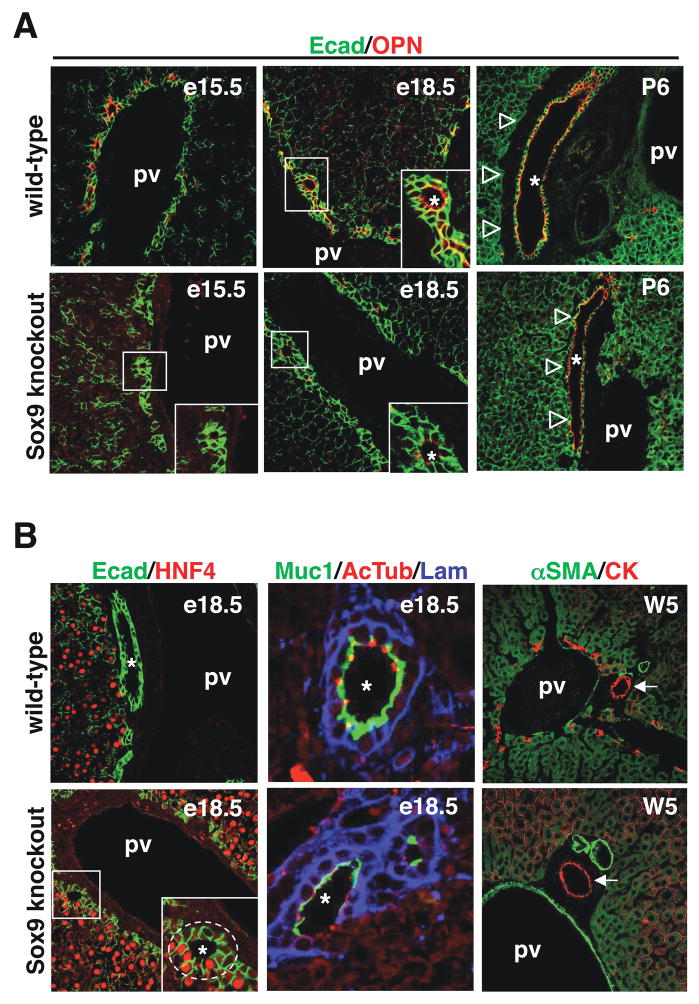

SOX9-deficient livers showed a ductal plate at e15.5. The formation of PDS was initiated, but no OPN expression was detected (Figure 5A). At e18.5, SOX9 knockout livers started to express low levels of OPN but still showed asymmetrical PDS: HNF4 was expressed on the parenchymal side and partial encircling of the PDS by laminin was observed (Figure 5B). We also looked at primary cilia, which are detectable as acetylated tubulin-stained dots, and at expression of mucin-1, a glycoprotein found at the apical pole of the biliary cells. In SOX9-deficient livers at e18.5, PDS cells expressed little or no mucin-1 and did only form very few primary cilia, in contrast to wild-type livers in which cilia had developed and mucin-1 was strongly expressed by the duct cells (Figure 5B). At postnatal day 6, bile ducts had developed in the knockout livers but their parenchymal side remained in contact with the hepatocytes, while wild-type ducts were totally surrounded by the periportal mesenchyme (Figure 5A). At five weeks of age SOX9-deficient bile ducts were normal and surrounded by periportal mesenchyme (arrows in Figure 5B). They were functional as determined by normal serum bilirubin levels (total and conjugated bilirubin in wild-type mouse: 0.33 and 0.08 mg/dl; in SOX9-deficient mouse: 0.36 an 0.09 mg/dl). Taken together, these data indicated that in the absence of SOX9, development of the bile ducts is characterized by the prolonged presence of asymmetrical PDS.

Figure 5.

SOX9 controls the timing of bile duct development. (A) SOX9-deficient livers showed delayed onset of OPN expression, and (B) persistence of asymmetrical PDS until e18.5 (Ecad/HNF4 and Muc1/AcTub/Lam stainings). (A) After birth, the SOX9-deficient ducts bile ducts were adjacent to the parenchyme, while wild-type embryos were surrounded by periportal mesenchyme. (B) At five weeks of age SOX9-deficient and wild-type mice had normal bile ducts, surrounded by periportal mesenchyme (αSMA/CK stainings). pv, portal vein; *, lumens of developing bile ducts.

In normal mice the ductal plates generate more than one duct and not all of them start to develop at exactly the same developmental time point, even when located at the same distance from the hilum. Therefore, at e18.5, asymmetrical PDS can be found near symmetrical ducts within a single portal tract, and the ratio of asymmetrical PDS to symmetrical ducts can be considered as an indicator of bile duct maturation. To quantify the delay in bile duct maturation in SOX9-deficient livers, we counted at e18.5 the ratio of asymmetrical PDS to symmetrical ducts. 157 wild-type and 105 SOX9 knockout portal tracts, stained for HNF4/E-cadherin or Laminin/E-cadherin, were analyzed. In wild-type livers the asymmetrical PDS/symmetrical duct ratio was 1.64, and in SOX9 knockout livers this ratio was 6.19. In wild-type and SOX9 knockout livers we found an average of 3.86 and 4.31 ductal structures per portal tract, respectively. The higher proportion of asymmetrical PDS in SOX9 knockout livers confirms that duct morphogenesis was delayed, the similar number of ducts per portal tract excluded that SOX9-deficient animals suffered from ductal paucity. We concluded that SOX9 controls the timing of bile duct morphogenesis.

SOX9 controls the expression of HES1, C/EBPα and TβRII

To position SOX9 in the network that regulates bile duct development, we looked at the expression of transcription factors and signaling mediators known to modulate biliary morphogenesis.

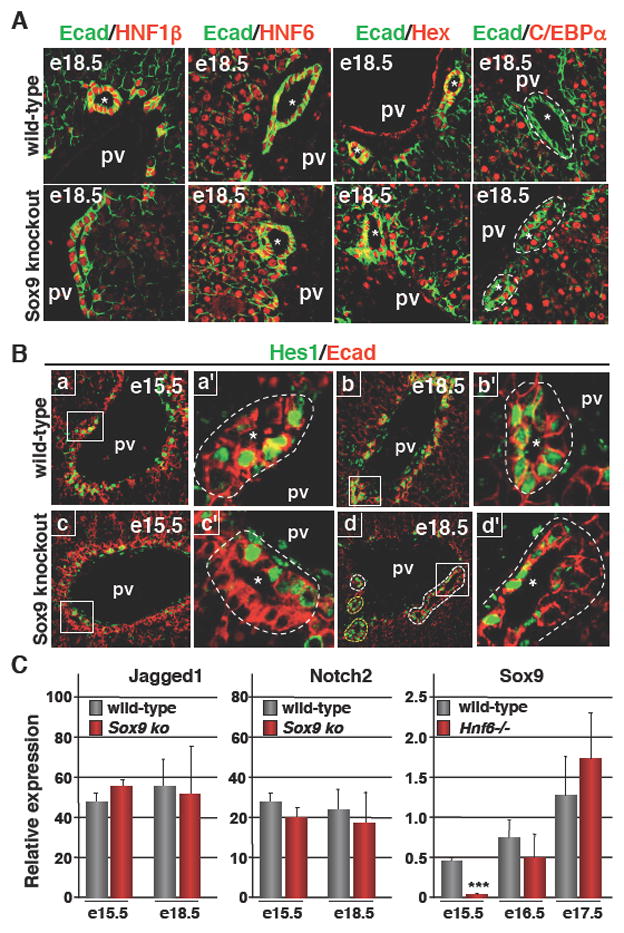

We first analysed the expression of HNF6 and HNF1β, two regulators of biliary morphogenesis8,12. Developing ducts of wild-type livers and PDS of SOX9-deficient livers expressed similar levels of HNF6 and HNF1β (Figure 6A), suggesting that the lack of SOX9 does not affect expression of the two factors. Consistent with the fact that the transcription factor Hex is upstream of HNF6 in the hepatic transcriptional network10, and with the normal expression of HNF6 in SOX9-deficient livers, we found that Hex is expressed normally in SOX9-deficient livers: indeed, both in wild-type and mutant livers, Hex was found in biliary cells and in hepatocytes (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

SOX9 and the transcriptional cascade regulating bile duct development. (A) Expression of HNF1β, HNF6 and Hex was normal in SOX9-deficient livers. In contrast to wild-type livers, C/EBPα expression was not repressed in the biliary cells of SOX9-deficient livers. (B) HES1 was expressed in the ductal plate and on the portal side of wild-type PDS, and was found at later stages in cells lining the parenchymal and portal sides of symmetrical ducts. In SOX9-deficient livers, expression of HES1 at e15.5 was normal, and by the end of gestation its expression pattern reflected the delayed bile duct morphogenesis. In panel Bd, PDS showing asymmetrical expression of HES1 were delineated by white dotted lines, while ducts which had reached symmetry and which expressed HES1 symmetrically were delineated by a yellow dotted line. a′, b′, c′ and d′ are magnified views of a, b, c and d. (C) The expression of Jagged1 and Notch2 was not significantly different between wild-type and SOX9-deficient livers. Expression of SOX9, measured by Q-PCR, was transiently downregulated in HNF6 knockout livers. Data are means ± SEM; n ≥ 3; *** P < 0.001. pv, portal vein; *, lumens of developing bile ducts.

C/EBPα, another regulator of biliary differentiation was expressed in wild-type parenchymal and ductal plate cells until e15.5 (data not shown), and was repressed in biliary cells at e18.5 (Figure 6A), consistent with earlier observations11. Interestingly, in the absence of SOX9, C/EBPα expression at e18.5 was maintained in the PDS: both the parenchymal side and the portal side expressed C/EBPα, indicating that SOX9 is required for repression of C/EBPα in biliary cells.

Notch signaling controls bile duct morphogenesis, and the best characterized mediators in this process are Jagged1, Notch2 and HES115–18. No evidence was found for abnormal expression of Jagged1 and Notch2 in SOX9-deficient livers (Figure 6C). In contrast, the lack of SOX9 perturbed HES1 expression. Indeed, in wild-type embryos, HES1 was expressed in several cells of the single layered ductal plate at e15.5, and the strongest expression was found on the portal side of the PDS with little or no expression on the parenchymal side (Figure 6B; a, a′). Later, at e18.5, wild-type cells lining symmetrical ducts expressed HES1 on the parenchymal and portal sides (Figure 6B; b, b′). In SOX9 knockout livers at e15.5, HES1 expression was similar to that in wild-type embryos. At e18.5, the persistent PDS expressed HES1 asymmetrically like at e15.5 (Figure 6B; c, c′, d, d′). Given the requirement of HES1 for bile duct development15 from the ductal plate, our data may suggest that the SOX9 -> HES1 cascade contributes to maturation of the ducts. Alternatively, the asymmetrical expression of HES1 in the PDS of SOX9-deficient livers may not contribute to but simply reflect the immaturity of bile duct development.

Given the involvement of TGFβ signaling in duct development (Figures 2 and 3A), we considered the possibility that SOX9 may regulate this signaling pathway. We analyzed the expression of TβRII in wild-type and SOX9-deficient livers and found that at e15.5, the expression of TβRII mRNA was significantly increased in the absence of SOX9 (Figure 3B). Moreover, immunostainings revealed that, in contrast to wild-type PDS, the expression of TβRII was symmetrical in SOX9-deficient PDS, since TβRII was found on both the parenchymal side and portal side of the PDS (Figure 3, compare panels in C with panels A;f, g). When the PDS progressively matured, expression of TβRII was eventually repressed in SOX9-deficient bile ducts. These data indicated that SOX9 modulates TGFβ signaling at the onset of PDS maturation.

Finally, when the expression of SOX9 was measured in HNF6 knockout livers, it was found to be downregulated (Figure 6C). This downregulation was transient but was parallel to the transient character of the biliary differentiation defect described earlier in HNF6 knockout livers8.

Taken together, our data indicate that SOX9 functions downstream of HNF6 to control the timing of bile duct maturation, possibly by regulating the expression of C/EBPα and of components of the Notch and TGFβ signaling pathways.

DISCUSSION

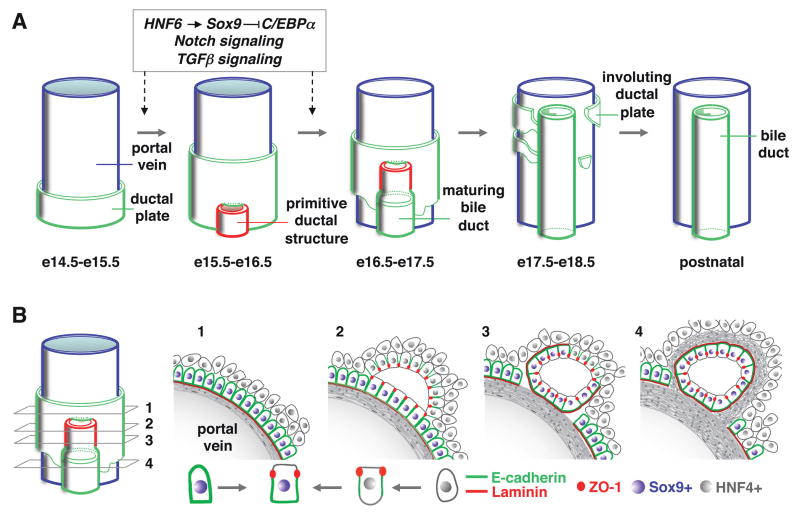

In this work we showed that biliary tubulogenesis starts with the formation of asymmetrical PDS lined by biliary cells on the portal side and by hepatoblasts on the parenchymal side. The PDS constitute a leading front of biliary tubes which develop along a longitudinal axis from the hilum towards the periphery and in which the hepatoblasts differentiate to biliary cells along the radial axis (Figure 7). To our knowledge this mode of tubulogenesis differs from other known models which have been classified as wrapping, budding, cavitation, or cord or cell hollowing27–30. Indeed, none of these models fit with bile duct development. We found no evidence for wrapping or budding, and unlike in the known models of cavitation and hollowing, there is no uniform circumferential signal at the onset of biliary tubulogenesis.

Figure 7.

(A) Model for the formation of bile ducts in mouse liver. The transition from single layered ductal plate to formation and maturation of primitive ductal structure is controlled by a HNF6-SOX9-C/EBPα cascade and by Notch and TGFβ signaling. (B) Schematic representation of the transient asymmetry in developing bile ducts.

How ducts grow along the longitudinal axis remains unknown. However, our data allow us to propose a model for differentiation along the radial axis. Indeed, the expression of hepatoblast markers on the parenchymal side of the PDS suggests that the asymmetry of PDS results from the apposition of hepatoblasts to biliary cells of the ductal plate. The binding of TGFβ ligands on the parenchymal side indicates that hepatoblasts may differentiate to biliary cells under influence of TGFβ to generate radially symmetrical ducts lined exclusively by biliary cells. Our experiments with cultured hepatoblasts correlate well with this in vivo expression profile: TGFβ can stimulate biliary markers and repress hepatoblast markers.

TGFβ signaling is unlikely to be the sole determinant of initiation of biliary tubulogenesis. Indeed, TGFβ is produced by a large portion of the periportal mesenchyme, and the mesenchyme is nearly completely encircled by the single-layered ductal plate. Yet, only a limited number of ducts form at focal areas of the ductal plate. Our data show that HES1 is expressed in several cells of the ductal plate but its expression is highest on the portal side of the PDS, in areas participating to duct development. Given its known role in initiation of biliary tubulogenesis15, high Notch signaling, via HES1, may act with TGFβ to promote differentiation along the radial axis.

SOX9 is shown here to be a specific and early marker of biliary cells. Therefore, SOX9 expression can be used for diagnostic purposes in biliary diseases. In addition, determining its expression will be useful to detect biliary contamination during programmed differentiation of stem cells to hepatocytes for cell therapy of liver diseases. The same holds true for OPN, a known marker for adult bile ducts31 which we now also found to be an embryonic biliary marker, but starting to be expressed later than SOX9 (Supplementary figure 1).

In the absence of SOX9, biliary morphogenesis is initiated but delayed from e15.5 until birth. It eventually produces functional ducts. SOX9 controls differentiation along the radial axis, since an excessive proportion of asymmetrical PDS persist near the hilum until birth. Serial sections along the hilum-periphery axis did not show evidence for a role of SOX9 in determining the longitudinal axis of duct development. Indeed, PDS were found in SOX9-deficient livers all along the hilum-periphery axis (not shown). In the absence of SOX9, HES1 expression was low or absent on the parenchymal side of the PDS at e18.5. Stimulation of HES1 by SOX9 was found by others to occur in the pancreas20. These data suggest that SOX9 may control HES1 in liver in a cell-specific way. Moreover, since expression of HES1 is perturbed on the parenchymal side of the PDS and not on their portal side in SOX9-deficient livers, the control exerted by SOX9 in liver is also cell type-specific. Our data also suggest that the low level or absence of HES1 on the parenchymal side of e18.5 PDS contributes to the delay in bile duct maturation of SOX9-deficient livers. However, we cannot eliminate the possibility that this expression of HES1 simply reflects immaturity, without contributing to it.

Our data establish a link between SOX9 and TGFβ signaling. Indeed, TβRII was repressed on the portal side of wild-type asymmetrical PDS, but not in SOX9-deficient PDS. How this impacts on the maturation of PDS cannot yet be determined with certainty. However the data suggest that during PDS formation, the cells on the portal side of the PDS instruct hepatoblasts to constitute the parenchymal side via cell-cell contacts. Such cell-cell contacts would together with TGFβ signaling promote biliary differentiation of hepatoblasts along the radial axis of the developing tubes. We speculate that persistent TGFβ signaling on the portal cells of the PDS in the absence of SOX9 perturbs the ability of these cells to induce biliary differentiation of cells on the parenchymal side.

Along the same lines, the persistent expression of C/EBPα in SOX9-deficient PDS may contribute to delayed maturation of the ducts. Indeed hepatoblasts devoid of C/EBPα preferentially differentiate to cholangiocytes rather than to hepatocytes11, suggesting that the opposite, namely persistence of C/EBPα, may inhibit biliary development.

Other potential targets of SOX9 are genes coding for extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. The delay in extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition around the PDS in SOX9 knockouts, the potential role of ECM in biliary morphogenesis32, and SOX9’s ability to stimulate ECM gene transcription in liver33, suggest that control of ECM production by SOX9 may be important for bile duct development. An involvement of SOX9 in repressing hepatoblast markers is unlikely since overexpression of SOX9 in cultured BMEL cells did not inhibit HNF4 expression (not shown). The transient nature of the defect in SOX9 knockouts may result from compensation by other SOX factors. Indeed, our preliminary data indicate that several SOX factors are expressed in developing liver (not shown).

Finally, humans with SOX9 deficiency suffer from campomelic dysplasia (OMIM #114290). Hepatic defects have not been reported, but considering the transient nature of the biliary anomalies, these might have been overlooked in humans. In any case, SOX9 dysfunction deserves to be investigated in cases of neonatal biliary anomalies of unknown origin.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table I: list of antibodies used for immunostaining experiments

Supplementary Table II: List of primer sequences used for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support. F.L. was supported by the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Program (Belgian Science Policy), the D.G. Higher Education and Scientific Research of the French Community of Belgium, the Alphonse and Jean Forton Fund, and the Fund for Scientific Medical Research. B.S. was supported by NIH grant DK076583. AA and PR hold fellowships from the Université catholique de Louvain. FC, CP and PJ are Research Associates of the F.R.S.-FNRS.

Abbreviations in this article

- C/EBPα

CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein α

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- Hex

hematopoietically expressed homeobox factor

- HES1

Homolog of Hairy/Enhancer of Split-1

- HNF

Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor

- OPN

osteopontin

- PDS

primitive ductal structures

- SOX9

SRY-related HMG box transcription factor 9

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- TβRII

transforming growth factor beta receptor type II

Footnotes

No conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kamath BM, Piccoli DA. Heritable disorders of the bile ducts. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:857–875. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(03)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemaigre F, Zaret KS. Liver development update: new embryo models, cell lineage control, and morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao R, Duncan SA. Embryonic development of the liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:956–967. doi: 10.1002/hep.20691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiojiri N. The origin of intrahepatic bile duct cells in the mouse. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;79:25–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Eyken P, Sciot R, Callea F, et al. The development of the intrahepatic bile ducts in man: A keratin-immunohistochemical study. Hepatology. 1988;8:1586–1595. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford JM. Development of the intrahepatic biliary tree. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:213–226. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemaigre FP. Development of the biliary tract. Mech Dev. 2003;120:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clotman F, Lannoy VJ, Reber M, et al. The onecut transcription factor Hnf6 is required for normal development of the biliary tract. Development. 2002;129:1819–1828. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clotman F, Jacquemin P, Plumb-Rudewiez N, et al. Control of liver cell fate decision by a gradient of TGFβ signaling modulated by Onecut transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1849–1854. doi: 10.1101/gad.340305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter MP, Wilson CM, Jiang X, et al. The homeobox gene Hhex is essential for proper hepatoblast differentiation and bile duct morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2007;308:355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamasaki H, Sada A, Iwata T, et al. Suppression of C/EBPα expression in periportal hepatoblasts may stimulate biliary cell differentiation through increased Hnf6 and Hnf1β expression. Development. 2006;133:4233–4243. doi: 10.1242/dev.02591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffinier C, Gresh L, Fiette L, et al. Bile system morphogenesis defects and liver dysfunction upon targeted deletion of HNF1beta. Development. 2002;129:1829–1838. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decaens T, Godard C, de Reyniès A, et al. Stabilization of beta-catenin affects mouse embryonic liver growth and hepatoblast fate. Hepatology. 2008;47:247–258. doi: 10.1002/hep.21952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan X, Yuan Y, Zeng G, et al. Beta-catenin deletion in hepatoblasts disrupts hepatic morphogenesis and survival during mouse development. Hepatology. 2008;47:1667–1679. doi: 10.1002/hep.22225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodama Y, Hijikata M, Kageyama R, et al. The role of notch signaling in the development of intrahepatic bile ducts. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1775–1786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lozier J, McCright B, Gridley T. Notch signaling regulates bile duct morphogenesis in mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geisler F, Nagl F, Mazur PK, et al. Liver-specific inactivation of Notch2, but not Notch1, compromises intrahepatic bile duct development in mice. Hepatology. 2008;48:607–16. doi: 10.1002/hep.22381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bastide P, Darido C, Pannequin J, et al. Sox9 regulates cell proliferation and is required for Paneth cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:635–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori-Akiyama Y, van den Born M, van Es JH, et al. SOX9 is required for the differentiation of Paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:539–546. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seymour PA, Feude KK, Tran MN, et al. SOX9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor cell pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2007;104:1865–1870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kist R, Schrewe H, Balling R, Scherer G. Conditional inactivation of Sox9: a mouse model for campomelic dysplasia. Genesis. 2002;32:121–123. doi: 10.1002/gene.10050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellendonk C, Opherk C, Anlag K, et al. Hepatocyte-specific expression of Cre recombinase. Genesis. 2000;26:151–153. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<151::aid-gene17>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacquemin P, Durviaux SM, Jensen J, et al. Transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 regulates pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation and controls expression of the proendocrine gene ngn3. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4445–4454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4445-4454.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Eyll JM, Pierreux CE, Lemaigre FP, et al. Shh-dependent differentiation of intestinal tissue from embryonic pancreas by activin A. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2077–2086. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margagliotti S, Clotman F, Pierreux CE, et al. The Onecut transcription factors HNF-6/OC-1 and OC-2 regulate early liver expansion by controlling hepatoblast migration. Dev Biol. 2007;311:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plumb-Rudewiez N, Clotman F, Strick-Marchand H, et al. The transcription factor HNF- 6/OC-1 inhibits the stimulation of the HNF-3α/Foxa1 gene by TGFβ in mouse liver. Hepatology. 2004;40:1266–1274. doi: 10.1002/hep.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lubarsky B, Krasnow MA. Tube morphogenesis: making and shaping biological tubes. Cell. 2003;112:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin-Belmonte F, Mostov KE. Regulation of cell polarity during epithelial morphogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogan BL, Kolodziej PA. Molecular mechanisms of tubulogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:513–523. doi: 10.1038/nrg840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung SY, Andrew DJ. The formation of epithelial tubes. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3501–3504. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorena D, Darby IA, Gadeau A-P. Osteopontin expression in normal and fibrotic liver. Altered liver healing in osteopontin-deficient mice. J Hepatol. 2006;44:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanimizu N, Miyajima A, Mostov KE. Liver progenitor cells develop cholangiocyte-type epithelial polarity in three-dimensional culture. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1472–1479. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanley KP, Oakley F, Sugden S, et al. Ectopic SOX9 mediates extracellular matrix deposition characteristic of organ fibrosis J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14063–14071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table I: list of antibodies used for immunostaining experiments

Supplementary Table II: List of primer sequences used for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.