Abstract

This article reviews current literature examining associations between components of the family context and children and adolescents’ emotion regulation (ER). The review is organized around a tripartite model of familial influence. Firstly, it is posited that children learn about ER through observational learning, modeling and social referencing. Secondly, parenting practices specifically related to emotion and emotion management affect ER. Thirdly, ER is affected by the emotional climate of the family via parenting style, the attachment relationship, family expressiveness and the marital relationship. The review ends with discussions regarding the ways in which child characteristics such as negative emotionality and gender affect ER, how socialization practices change as children develop into adolescents, and how parent characteristics such as mental health affect the socialization of ER.

Keywords: emotion regulation, context, family, parenting

In the last two decades, there has been a substantial increase in psychology and popular culture’s interest in human emotionality and the ways in which individuals express and manage emotions (e.g., Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004; Denham, 1998; Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992; Fox, 1994; Garber & Dodge, 1991; Goleman, 1995). This interest is due in part to an increase in developmental research and theory suggesting that an essential component of children’s successful development is learning how to regulate emotional responses and related behaviors in socially appropriate and adaptive ways (Denham et al., 2003; Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Morris, 2002; Halberstadt, Denham, & Dunsmore, 2001; Kopp, 1992; Saarni, 1990). Research in developmental psychopathology also stresses the role of emotion regulation (ER) in development, and has linked difficulty in regulating negative emotions such as anger and sadness to emotional and behavioral problems (Cicchetti, Ackerman, & Izard, 1995; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg, Guthrie, et al., 1997; Frick & Morris, 2004; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003).

Many factors influence the development of ER. Child temperament, neurophysiology and cognitive development all play important roles (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Goldsmith & Davidson, 2004). Nonetheless, emotions are recognized as both products and processes of social relationships (Cole et al., 2004; Parke, 1994; Walden & Smith, 1997). Despite several decades of research on the importance of the social context, particularly the family, until recently there has been little research on the influence of social relationships in the development of ER abilities. In this review we suggest that one of the ways in which relationships affect children’s psychosocial development is through their impact on children’s ER (see also Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Eisenberg & Valiente, 2004; Power, 2004). Indeed, although most psychologists agree that the family context has a major impact on children and adolescents’ social and emotional development, the mechanisms through which context impacts development are less clear (Darling & Steinberg, 1993).

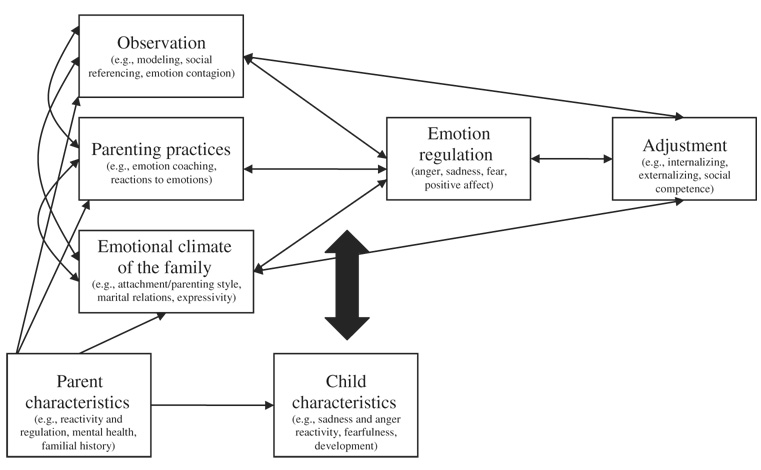

In this review we argue that the family context affects the development of ER in three important ways (see Figure 1). Firstly, children learn about ER through observation. Secondly, specific parenting practices and behaviors related to the socialization of emotion affect ER. Thirdly, ER is affected by the emotional climate of the family, as reflected in the quality of the attachment relationship, styles of parenting, family expressiveness and the emotional quality of the marital relationship. Additionally, throughout this review we highlight the impact of socialization practices in middle childhood and adolescence. Because there is little research on family socialization of ER during adolescence, we discuss how early socialization affects ER throughout development, and the ways in which early socialization practices set the foundation for later socialization and related developmental changes. The last section of the review examines how individual characteristics, such as children and parents’ emotionality, and the family context work together to influence overall emotional development; and how socialization practices change as children develop into adolescents. Suggestions for future research are highlighted throughout the article and are also summarized at the end of the review.

Figure 1.

Tripartite Model of the Impact of the Family on Children’s Emotion Regulation and Adjustment.

Eisenberg et al. (1998) reviewed the parenting literature on the socialization of emotion in a seminal review article. The current review expands upon that work in several important ways. Firstly, research published since 1998 is reviewed, including a significant amount of additional research on ER. Secondly, this review focuses more broadly on the family, also including studies of the marital relationship, and focuses more narrowly on the socialization of ER, rather than overall emotion socialization, which includes the socialization of emotional competence more globally. Relevant definitional and measurement issues regarding the socialization of ER are not discussed in depth, as these topics are discussed in other current reviews (see Bridges, Denham, & Ganiban, 2004; Eisenberg & Spinrad, 2004) and are beyond the scope of this article.

The Study of Emotion Regulation

Research on the construct of ER has only recently begun to burgeon (Cole et al., 2004; Fox, 1994). Existing empirical studies of ER differ widely in the measures, methods and levels of analyses employed (Eisenberg, Morris, & Spinrad, 2005; Morris, Robinson, & Eisenberg, 2005; Raver, 2004; Underwood, 1997; Walden & Smith, 1997). Although methods of assessment vary widely, Thompson (1994, p. 27) argues that ‘researchers share a common intuitive understanding of what is meant by ER’ (see also Cole et al., 2004; Underwood, 1997). The definition of ER adhered to in this review comes from Thompson (1994) and similar definitions are offered by Eisenberg and Morris (2002), Eisenberg and Spinrad (2004), Eisenberg et al. (1997), Grolnick, Bridges, and Connell (1996) and Kopp (1989):

Emotion regulation consists of internal and external processes involved in initiating, maintaining, and modulating the occurrence, intensity, and expression of emotions.

Several components of this definition deserve further explanation in the context of the current review (see also Thompson, 1994). Firstly, ER includes internal and external processes. The study of ER concerns internal processes employed to manage emotions, such as emotional cognitions, attention shifting and the management of physiological responses, as well as the role of external influences, such as parents or other individuals, who help in the modulation of emotions. For young children, a considerable amount of ER occurs through the actions and intervention of others (Kopp, 1989; Thompson, 1994). As children develop, they rely less on parents to aid in ER, and often utilize other socialization agents, such as peers (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Silk et al., 2003). Additionally, ER processes modulate the intensity and expression of emotions. Specifically, ER mechanisms modulate what Thompson (1990) calls emotional tone, the specific emotion experienced (e.g., anger, sadness, joy), and emotional dynamics (e.g., intensity, duration, lability). Finally, investigators must also consider the specific processes involved in modulating and maintaining emotional experiences, processes referred to as ER strategies, or coping strategies associated with emotion management (Brenner & Salovey, 1997). Thus, in this review, we include studies examining all components of ER that involve familial influences on these processes.

The above definition also implies that ER connotes an ability to respond in a socially appropriate, adaptive and flexible manner to stressful demands and emotional experiences (Cole, Michel, & Teti, 1994; Eisenberg & Morris, 2002;Walden & Smith, 1997). Emotions serve important expressive and communicative functions, and, from a functionalist perspective, serve to energize, motivate and guide adaptive functioning (Campos, Campos, & Barrett, 1989; Thompson, 1990). While strong negative emotions can be adaptive, such as in the context of threat or fear, strong emotional arousal can become maladaptive when it does not match contextual or social demands (Cicchetti et al., 1995). An essential objective in the development of ER then is for children and adolescents to learn ways in which to manage emotions in socially and contextually appropriate ways (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Kopp, 1992).

The Tripartite Model of the Impact of the Family on Children’s Emotion Regulation and Adjustment

As seen in Figure 1, our model illustrates processes involved in familial socialization of ER, the role of parent and child characteristics in the socialization of ER, and the mutual effects of these processes/characteristics on overall adjustment. In our model, socialization of ER occurs via three processes: observation/modeling, parenting practices and the emotional climate of the family (including parenting style). We distinguish between parenting practices (specific parental behaviors defined by content and socialization goals), and parenting style (parent’s attitudes toward the child which create an emotional climate) in our model, because we believe that this distinction is important in understanding the ways in which parents influence development (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Children’s ER and familial influences are bidirectional processes in our model, supporting a family systems view where children and families mutually influence one another throughout development.

We posit that parental characteristics (e.g., parental reactivity and ER, mental health, and familial history) influence what the child observes, parenting practices, the emotional climate of the family and child characteristics. Specifically, parents’ own beliefs regarding emotions, their own parent–child relationship and attachment status, and their ability to control their own emotions, affect emotion socialization and the ways in which parents interact with children and other family members (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1997). Moreover, children’s own reactivity and regulation are affected to some degree by inherited traits from parents (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002).We posit that child characteristics, such as children’s vulnerability to experiencing negative emotions, moderate relations between family context variables and children’s ER, such that children who are high in reactivity are most at risk for developing emotion regulatory difficulties when living in a negative family environment. Children’s own developmental status also affects the ways in which family factors impact ER. For example, a young child is more dependent on parents’ attempts to aid in ER, whereas an adolescent may rely more on peers for such support (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002).

Our model also illustrates that although there are direct effects of the family context on children’s adjustment (e.g., internalizing, externalizing, social competence), much of the effects of the family context on children’s psychosocial development occur via the impact of the family on children’s ER (see Eisenberg et al., 2003; Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001), thus a mediational model is proposed. Indeed, there is a burgeoning amount of evidence supporting such a view. For example, Contreras, Kerns, Weimer, Gentzler, and Tomich (2000) found that the association between maternal attachment and peer competence was explained by the effects of attachment on children’s ER (assessed as constructive coping). Similarly, Volling, McElwain, and Miller (2002) found that children’s effortful control mediated the relation between maternal emotional availability and child compliance in toddlers. Eisenberg and colleagues have demonstrated that ER is a link between parenting and child adjustment in several studies (e.g., Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001). For example, they found that the effects of parental behavior on children’s externalizing behavior was indirect through children’s regulation of emotion (Eisenberg, Losoya, et al., 2001). Although adjustment is the outcome of our model, in this review we focus primarily on the socialization of ER and individual characteristics that affect the socialization process, and discuss findings on adjustment only when examined as part of a study reviewed.

The processes described in this model are, of course, imbedded in culture. Culture affects the ways in which parents interact with children (specific parenting practices), the emotional climate of the family (e.g., via display rules, and gender roles), and the ways in which emotions are interpreted, expressed and reacted to by others (see Saarni, 1990). Despite such an important influence, the role of culture in the socialization of ER is beyond the scope of this review.

The Family Context and Emotion Regulation

The environment that children experience affects their overall growth and development in many important ways. Children’s families, schools, neighborhoods, peers and culture all play a role in emotional development. Despite these important contextual influences, most research to date on ER and context has focused primarily on parental influences (for exceptions see Aucoin, Morris, &Terranova, 2007; Volling, McElwain, & Miller, 2002), and more work is needed on how other important contextual factors such as peers, school, culture and neighborhood affect ER. This will be especially important for understanding how adolescents regulate emotion because of the prominence of the extra-familial social context in adolescents’ lives (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). It should be noted that most research on ER and the family context has focused primarily on the mother–child relationship; however, fathers and siblings play an important role in children’s development of ER, despite little empirical evidence on this issue (for exceptions see Volling, McElwain, et al., 2002; Zeman Penza, Shipman, & Young, 1997).

Observing/Modeling Emotion Regulation in the Family

One mechanism through which families influence ER is via children and adolescents learning about emotions and ER by observing parents’ emotional displays and interactions (Parke, 1994). Modeling has long been demonstrated as an important mechanism through which children learn specific behaviors (Bandura, 1977). Theory and research regarding modeling, emotion contagion and social referencing provide some evidence for the observational learning of ER processes. The modeling hypothesis suggests that parents’ own emotional profiles and interactions implicitly teach children which emotions are acceptable and expected in the family environment, and how to manage the experience of those emotions. Children learn that certain situations provoke emotions, and they observe the reactions of others in order to know how they ‘should’ react in similar situations (Denham, Mitchell-Copeland, Strandberg, Auerbach & Blair, 1997). Some parent–child emotional interactions are likely to be particularly salient. For example, when parents often display high levels of anger toward children in frustrating situations, children are less likely to observe and learn effective ER responses. In addition, parents’ overall expressivity, which will be discussed in more detail in a subsequent section, may affect children and adolescent’s modeling of ER; if parents display a wide range of emotions freely, children learn about the appropriateness of different emotions across different situations, as well as about a variety of emotional responses (Denham et al., 1997).

Emotion Contagion

The overall amount of emotion in the family, particularly negative emotionality, may actually induce negative emotions in children. Studies suggest that emotion contagion, or the ‘catching’ of an emotion, occurs in early infancy and beyond (Saarni, Mumme, & Campos, 1998). Emotion contagion is said to occur when a facial, vocal or emotional gesture generates a similar response in another person (Saarni et al., 1998). Most research on emotion contagion to date has focused on negative emotions; however, emotions such as laughter are important in emotion socialization and overall parenting, and more research on the transmission of positive emotions in general is an area worthy of study.

Social Referencing and Modeling

Another way that children and adolescents learn about emotions and ER is through social referencing. Social referencing is the process of looking to another person for information about how to respond, think or feel about an environmental event or stimuli (Saarni et al., 1998). There are few, if any, specific studies of social referencing in older children and adolescents, but it can be assumed that older children also look to parents during novel situations in order to acquire information regarding possible emotional responses, and in order to learn ways in which to manage emotions resulting from stressful situations. Indeed, Emde, Biringen, Clyman, and Oppenheim (1991) posited that when a child is put into a stressful situation, referencing of the parents’ emotion-related message allows the child to access internal depictions of parental emotion, determine the affective meaning, and to begin to regulate emotions and behaviors accordingly (see also Barrett & Campos, 1987). During adolescence, it is likely that peers also are utilized as social referencing agents. Adolescents often look toward peers in order to gain information about how to respond to social and emotional situations (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Moreover, adolescents experience certain emotions, like hopelessness and romantic loss/love, for the first time due to cognitive advances in functioning (Steinberg & Silk). It may be that for these types of emotional experiences, adolescents look to parents and peers in order to ‘learn’ how to deal with such emerging issues as sexuality, independence and intimacy. Research on such topics is greatly needed.

There is some evidence that children actually model parents’ strategies for regulating emotion (Parke, 1994). For example, children exposed to maternal depression have a limited repertoire of ER strategies, and they utilize strategies that are considered to be less effective compared with children of never depressed mothers (Garber, Braafladt, & Zeman, 1991; Silk, Shaw, Skuban, Oland, & Kovacs, 2006). It is likely that in normative samples, children also learn/model adaptive vs. maladaptive strategies for managing emotions. These behaviors may just be more evident in non-normative samples and in early childhood when children are first actively learning about ER.

It is difficult for researchers to separate observational learning effects from specific emotion socialization processes and the emotional climate of the family. Most likely, these processes occur in tandem to influence the development of children and adolescents’ ER. Nevertheless, it is clear that children model emotions and learn about emotion regulatory processes through experiences in the family; and that experiences with, and observations of, parents, siblings and marital interactions build a foundation for emotional discourse and the development of ER.

Emotion-related Parenting Practices

Although there is a considerable amount of research on parenting practices associated with the socialization of emotion in general, that is, the ways in which parents teach children about emotions (see Eisenberg et al., 1998), much of this work has focused primarily on the socialization of emotion understanding rather than the socialization of ER specifically. In general, research on children’s emotion understanding suggests that the family’s positive emotional expressivity, discourse about emotions, and acceptance of emotional displays are related to higher levels of emotion understanding and emotional competence (e.g., Denham et al., 1997; Denham et al., 2003; Dunn & Brown, 1994). In this review, we focus specifically on how families influence children’s ER, but parental influences on the socialization of emotion more broadly are also important to consider (see Denham, 1998; Eisenberg et al., 1998).

Emotion-coaching

Gottman and colleagues have been among the first to examine emotion-related parenting practices and their link to children’s ER. Gottman et al. (1996, 1997) argue that parents who are responsive and warm typically display specific types of parenting behaviors and have certain beliefs associated with emotion that affect children’s ER. They posit a theory of meta-emotion philosophy, which reflects an individual’s organized set of beliefs and feelings about one’s own emotions and one’s children’s emotions. Parents’ meta-emotion philosophy is related to their emotion-coaching which involves the following parental behaviors: parents are aware of the child’s emotion; they see the child’s emotion as an opportunity for intimacy or teaching; they help the child to verbally label his/her own emotions; they empathize with or validate the child’s emotion; and they help the child to problem-solve (Gottman et al., 1997, p. 84). In contrast, emotion-dismissing parenting involves a parent being uncomfortable with the expression of emotion and who tends to disapprove of or dismiss emotional expression. Results based on extensive dyadic observations between parents and 5- to 8-year-old children suggest that some parents do serve as ‘emotion coaches’, guiding or coaching children through the process of regulating emotions. In a small longitudinal study, parents’ emotion-coaching behaviors were linked to children’s ER (as reported by parents), as well as to levels of vagal tone (a parasympathetic indicator of regulation; Gottman et al., 1996). However, these findings need to be reproduced in larger, more diverse samples.

Parents’ Reactions to Emotions

Parents also affect children’s ER by their specific reactions to children’s negative and positive emotions (Eisenberg et al., 1998). Eisenberg and colleagues have conducted an extensive empirical investigation of parental responses to negative emotions, typically assessed via parent report of responses. This work is based on the idea that punitive or negative parental responses to children’s emotional displays serve to heighten children’s emotional arousal and teach children to avoid rather than to understand and appropriately express negative emotions such as sadness and anger.

Consistent with this theory, punitive parental reactions to children’s emotions have been linked to inappropriate ER strategies (escape or revenge-seeking) in real-life anger provocations (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1994; Eisenberg, Fabes, Carlo, & Karbon, 1992), and to overall lower levels of socio-emotional competence (Jones, Eisenberg, & Fabes, 2002). Parental minimization of children’s emotions has been linked with avoidant ER strategies in early and middle childhood (Eisenberg, Fabes, Carlo, & Karbon, 1992; Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996). Similarly, parental negative and dismissing responses have been associated with increased displays of child anger in observed parent–child interactions (Snyder, Stoolmiller, &Wilson, 2003). In contrast, maternal problem-focused reactions have been positively related to children’s constructive coping (Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996). Longitudinal analyses indicate that in general, parents’ negative reactions to children’s emotions are associated with low quality of social functioning and ER difficulties. Moreover, the relation between children’s problem behavior and parental punitive or distress reactions is bidirectional (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Eisenberg et al., 1999).

Parental Encouragement of and Perceived Control over Emotions

Roberts and Strayer (1987) found that parental encouragement of children’s display of negative affect had a curvilinear relationship with children’s overall competence, suggesting that parents who overly discouraged or encouraged children’s negative emotional displays had children with more adjustment problems. In line with this suggestion, Denham (1993) found that parents’ calm/neutral reactions to children’s anger were associated with lower levels of expressed anger and fearfulness in other contexts. Berlin and Cassidy (2003) examined how attachment classifications at 15–18 months predicted maternal control over preschooler’s emotional expression. They found that insecure-avoidant mothers reported greater control over their children’s negative emotional expression compared with other mothers, and that insecure-ambivalent mothers reported less control over children’s negative emotional expression compared with other mothers. Additionally, mothers who reported greater control had children who were less likely to express their feelings and display anger in an emotion-eliciting task. The implications of these studies are that there may be an ‘optimal’ level of control where parents want to allow the expression of negative emotions, but not overly encourage their expression. It should be noted, however, that in the latter study, parental bias in reporting (e.g., beliefs about their children and their parenting) likely contributed to the ways in which parents view emotional control of their children. However, the prior studies cited utilized observational methods to assess parental reactions, thus strengthening the validity of the findings.

Teaching About Emotion Regulation Strategies

In addition to parental reactions to children’s emotions, parents also may intentionally teach their children strategies for regulating emotion. For example, parents sometimes provide children with specific suggestions for coping with negative emotions (e.g., take a deep breath, think about something nice). One study found that when children were presented with a disappointing prize, parents’ attempts to aid children in cognitively reframing the situation so that it was no longer negative (e.g., we can use these socks as puppets) and parental attempts at redirecting attention away from the prize were associated with lower levels of expressed sadness and anger (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Aucoin, & Keyes, 2007). Similarly, Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, and Lukon (2002) found that children’s attention shifting and seeking information during a frustration task, in which the mother was present, were associated with lower levels of expressed anger.

Niche-picking

A final parenting practice that may be related to the development of ER is ‘niche-picking’. Niche-picking involves parents selectively choosing or avoiding opportunities for their children to experience emotional stimuli. In this manner, parents regulate opportunities for children to learn about and experience emotions (Parke, 1994). Niche-picking acts as a mode of extrinsic regulation, but it also teaches the child that they can select or avoid emotional contexts as a way of regulating emotion proactively (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997); however, it should be noted that child characteristics, such as a fearful temperament, and children’s behavior in certain contexts may affect parents’ choices of activities/niches. Unfortunately, there is little to no research on this potential domain of parental influence on children’s ER, and more work is needed in order to examine the usefulness of niche-picking as it may reflect overprotective parenting in some cases, which may have maladaptive effects on children’s and adolescents’ adjustment (Morris, Steinberg, Sessa, Avenevoli, Silk, & Essex, 2002).

Emotional Climate of the Family

The emotional climate that children experience daily has an important impact on overall emotional development and ER. The emotional climate of a family is reflected in relationship qualities (such as attachment, marital relationships and parenting styles) and in the amount of positive and negative emotion displayed toward members of the family (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). When a child’s emotional climate is negative, coercive or unpredictable, children are at risk in becoming highly emotionally reactive, due to frequent, unexpected emotional displays or because of emotional manipulations. In these kinds of environments, not only are children observing emotion dysregulation in their parents, but they are less emotionally secure (Cummings & Davies, 1996). In contrast, when children live in a responsive, consistent environment in which they feel accepted and nurtured, they feel emotionally secure and free to express emotions because they are certain their emotional needs will be met. Children also feel secure emotionally when they know what behaviors are expected and what the consequences will be when they misbehave (Eisenberg et al., 1998).

The emotional climate of the family is a reflection of a variety of intra-familial processes and dynamics. There are four important components of the emotional environment that likely affect the development of ER: the overall predictability and emotional stability of the environment; parental expectations and maturity demands; the degree of positive emotionality expressed in the family; and the degree of negative emotionality expressed in the family. These components of the family emotional climate are typically examined in research via studies of (1) parent–child attachment, (2) parenting style, (3) family expressivity, (4) expressed emotion and (5) marital relations.

Parent-child Attachment

Parent–child attachment can be thought of as a reflection of the emotional climate between the parent and the child. In the first few years of a child’s life, the parent is responsible for much of a child’s ER, and parents must respond to children’s emotional needs in a consistent, nurturing manner that facilitates the development of a secure emotional attachment to the caregiver.

There is evidence that early attachment predicts later ER. For example, Gilliom et al. (2002) found that secure attachment at age one and a half predicted effective ER at age three. Similarly, in a sample of 5th graders, Contreras et al. (2000) found that constructive coping, conceptualized as successful ER, was associated with more secure attachment (as reported by children); the relation between attachment and social competence among peers was mediated by children’s constructive coping, suggesting that one way in which attachment affects adjustment is via its impact on children’s ER. Research on adolescents using the adult attachment interview (AAI; Main & Goldwyn, 1984) indicates that adolescents classified as viewing their attachment relationship with their parents as more secure, are higher in ER (assessed as ego resiliency) and lower in anxiety and hostility compared with dismissing and preoccupied groups, which reflect more insecure attachment models (Kobak & Sceery, 1988). Although more longitudinal research in this area is needed, these studies provide evidence for links between early attachment and later ER.

Parenting Style

Parenting style reflects parental attitudes and behaviors toward children that, taken together, help to create the emotional climate of the family (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Different parenting styles are generally defined by variations in parental responsiveness and demandingness. Responsive parents are nurturing and child-centered (much like the parents of securely attached infants). Demanding parents have high, yet reasonable expectations for children and enforce rules in a consistent, flexible manner (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Research suggests that different parenting styles are differentially associated with children’s emotional and social development (Baumrind, 1971; Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Parke & Buriel, 1998); and, as reviewed below, there is some evidence that specific components of parenting style (e.g., responsiveness) are related specifically to children’s ER.

Research with young children has demonstrated links between maternal responsivity to children’s emotional cues and children’s use of self-regulatory behaviors (Cohn & Tronick, 1983; Gable & Isabella, 1992). Variations of the style of parental responsiveness, such as acceptance, support and sympathy, have also been linked with the development of ER in older children. For example, 4th- and 5th-grade children’s reports of maternal acceptance have been associated with optimal active and support-seeking ER strategies (Kliewer, Fearnow, & Miller, 1996). Similarly, in a study with 9–10-year-old children (Hardy, Power & Jaedicke, 1993), maternal support was associated with access to a wider range of ER strategies in children, as well as the use of ER strategies viewed as more appropriate. Maternal sympathy and observed responsiveness have also both been associated with lower levels of observed negative emotions in children (Eisenberg, Fabes, Schaller, Carlo, & Miller, 1991; Fabes et al., 1994), which likely has an impact on their ER although not directly assessed.

Studies also find that negative parenting (e.g., hostility, psychological control, negative control, lack of sensitivity) is associated with poor ER. Using an observational emotion-eliciting task, Calkins, Smith, Gill, and Johnson (1998) found that maternal negative behavior (e.g., scolding, anger, physical control) was associated with poor observational and physiological (vagal tone) ER. Similarly, Morris, Silk, et al., (2002) found that child report of maternal hostility was associated with lower parent reported child ER, assessed as effortful control. In one of the few longitudinal studies to examine ER in young children, maternal lack of sensitivity and stimulation, as well as depressive symptoms, predicted children’s emotion dysregulation as assessed during mother–child interaction tasks. Children lower in ER had more adjustment problems in kindergarten and 1st grade, suggesting lasting effects of ER difficulties which occur within the parent–child dyad (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004).

A growing body of research examining ER specifically among maltreated children also sheds light on the ways in which maladaptive parenting impacts the development of ER. Maltreatment early on in development is such an aberration in the parent–child relationship that ER deficits can occur for a variety of reasons such as lack of modeling and support, absence of positive affect, harsh discipline and negative control, inconsistency, and lack of sensitivity (Shipman & Zeman, 1999, 2001). For example, Erickson, Egeland, and Pianta (1989) studied dyadic interactions between young children and abusive caregivers. In these interactions, overall the children were negative, noncompliant, and impulsive, and they lacked self-control. Research also indicates that maltreated children often have difficulties understanding negative affect (Frodi & Lamb, 1980; Shipman, Zeman, Penza, & Champion, 2000; Waldinger, Toth, & Gerber, 2001) possibly because of the indiscriminate hostility experienced in interactions with their parent. Rogosch, Cicchetti, and Aber (1995) found the relationship between maltreatment and affect dysregulation was accounted for by maltreated children’s poor understanding of negative affect. Poor understanding of negative affect also explained the relationship between maltreatment and social isolation, suggesting how important understanding of affective cues is in predicting maltreated children’s adjustment.

There is some evidence for links between emotion dysregulation, parenting and psychopathology among maltreated children. For example, Maughan and Cicchetti (2002) investigated maltreated preschoolers and their parents during an anger simulation procedure. About 80 percent of the maltreated children exhibited dysregulated emotion patterns (either undercontrolled or overcontrolled) in response to simulated anger. Similarly, in a parent–child observational task, Robinson, Morris, Heller, Smyke, and Boris (2007) found that parental anger and positive affect were associated with maltreated and non-maltreated children’s observed ER in expected directions. Moreover, parental anger was associated with higher levels of internalizing symptoms among maltreated children, suggesting that parental affect may have a stronger impact in the maltreating dyad. Despite the studies reviewed, there are few studies that have investigated ER from the perspective of the maltreating parent–child dyad, as evidenced by the fact that many studies have described regulation in reference to peer relationships (e.g., Alessandri, 1991; Bolger & Patterson, 2001; Shields, Cicchetti & Ryan, 1994; Shields, Ryan & Cicchetti, 2001).

In summary, overall results on the relation between parenting style and children’s emotional development suggest that parental responsiveness and negativity are important components of the emotional climate because of their effects on children’s emotionality, emotional competence and ER. However, there are many limitations in the extant research. Firstly, few studies examining parenting styles and ER also analyze the moderational role of child characteristics (e.g., the ways in which parenting and children’s emotionality interact to predict ER). Secondly, many studies assess children’s overall emotionality and emotional competence, without directly addressing ER, or the specific emotion being expressed. Thirdly, few studies have examined the relation between parental demandingness/discipline and children’s ER. Finally, as mentioned previously, there is little research on the impact of parenting styles on adolescents’ ER and longitudinal studies examining links between parenting and ER over time are greatly needed.

Family Expressivity

Another mechanism through which the family impacts children’s ER is through the amount of emotion, both positive and negative, expressed verbally and non-verbally in the family. Most research on family expressivity has focused on parental expression of emotion; however, the emotional self-expression of each family member contributes to overall family expressiveness and the emotional climate of the family. There is a burgeoning amount of evidence suggesting that parental expression of emotion is related to children’s socio-emotional development. Parental expression of positive emotion has been linked to children’s prosocial behavior, social competence, emotion understanding, positive emotionality, and quality of the parent–child relationship (Cumberland-Li, Eisenberg, Champion, Gershoff, & Fabes, 2003; Dunn & Brown, 1994; Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2003; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994; Rubin, Hastings, Chen, Stewart & McNichol, 1998). Parental expression of negative emotion tends to be associated with poorer developmental outcomes, such as externalizing behavior, but findings are inconsistent across studies (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Halberstadt, Crisp, & Eaton, 1999). This inconsistency in findings for negative expression of emotion is likely due to researchers’ lack of distinction between the negative emotions expressed (e.g., anger vs. sadness), the frequency and intensity of the expressed emotion, and not knowing whom in the family the emotion is directed toward (Halberstadt et al., 1999). Further, evidence suggests that there may be a curvilinear relationship between negative expressivity and children’s socio-emotional development. Specifically, mild and moderate degrees of negative emotional expression may actually aid children in learning about emotions and ER by exposing them to a variety of emotions and how emotions can be managed. In contrast, high levels of negative emotional expression likely have a deleterious impact on children’s development because of the distress caused by this level of negative expression and children not seeing their parents model successful regulation. There is also evidence that children of parents who are emotionally expressive in the family are more likely to be emotionally expressive themselves (Halberstadt, 1986; Halberstadt et al., 1999).

There are very few studies that specifically examine family expressivity and ER. Of these few, findings do suggest a link between this component of the family context and children’s ER. For example, Garner and Power (1996) found that negative maternal expressiveness was related to lower levels of children’s expressed negative emotions during a disappointment task. In a study conducted by Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al. (2001), positive and negative expressed family emotion was associated with children’s ER in expected directions. Further, ER mediated the link between parental expressiveness and children’s adjustment and social competence, suggesting regulation is an important link to consider when examining the effects of parenting on children’s development. Eisenberg et al. (2003) followed up these same children two years later and found similar patterns for positive expressivity; however, the effects for negative expressivity changed with age.

Positive family expressiveness, in particular, has been associated with ER in at least two studies. Firstly, children left alone in a lab with an older sibling and a stranger, or just an older sibling, displayed more self-soothing behaviors when they were from families with higher levels of positive expressivity (Garner, 1995). Secondly, teachers rated kindergartners as higher in ER if they were from more positively expressive families (Greenberg, et al., 1999). As mentioned previously, research findings on the relation between negative expressivity, specifically, and ER are less clear (Halberstadt et al., 1999).

It is likely that parental expressivity is linked to overall parenting style and specific parenting behaviors. Indeed, parents who express a great deal of positive emotions in the family are likely warm and supportive, and respond to children’s emotions in accepting ways; whereas parents who display negative emotions in the family are likely hostile toward their children and are less responsive to their children’s displays of emotion. Thus, parents who express positive emotions are likely authoritative parents (warm yet firm) and parents who express negative emotions may be more authoritarian (cold and firm) in nature (Halberstadt et al., 1999).

Expressed Emotion

Research on the construct of expressed emotion may also be important to consider in understanding the role of the familial emotional climate in children’s development of ER. Expressed emotion is an index of negative dimensions of the affective climate of the family environment. Originally studied among the families of adult psychiatric patients, expressed emotion (EE) provides a measure of the level of criticism and emotional over-involvement expressed by parents (or other relatives) when describing the relationship between themselves and the patient. A large body of literature demonstrates that high expressed emotion, particularly criticism, is a predictor of poor clinical outcome in adult depressed and schizophrenic patients (for a review see Wearden, Tarrier, Barrowclough, Zastowny, & Rahill, 2000). Findings suggest higher rates of critical expressed emotion in the families of children and adolescents with depressive disorders (Asarnow, Tompson, Hamilton, Goldstein, & Guthne, 1994; Asarnow, Tompson, Woo, & Cantwell, 2001) and disruptive behavior disorders (Hibbs, Hamburger, Lenane, & Rappaport, 1991; Schwartz et al., 1990; Vostansis, Nicholls, & Harrington, 1994). Although no research has directly tested this model, disrupted ER is a likely mechanism through which parental expressed emotion influences children’s adjustment.

Marital Relations

Inter-adult conflict, among married parents, long-term partners, or grandparents and parents, is an important context of the family in which children can learn adaptive and/or maladaptive ways to manage conflict and related emotions (Cummings & Davies, 1994). These adult relationships contribute significantly to the emotional climate of the family, and many studies have linked martial conflict to adjustment difficulties in both children and adolescents (Cummings & Davies, 2002). Research suggests that children exposed to ‘background anger’, even when it is not directed toward the child, places children at risk for the development of social and emotional problems (Lemerise & Dodge, 1993). Davies and Cummings (1998, 1994) posit a mediational model of children’s emotional security and marital conflict (see also Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2002). They suggest that the link between marital conflict and child adjustment is via children’s emotional security, one component of which is ER (see Davies & Cummings, 1998).

Davies and Cummings (1998) empirically tested whether links between child adjustment and marital conflict were mediated by children’s emotional security, as evidenced by emotional reactivity, regulation to exposure of parent affect, and internal representations of the marital relationship. Children at the ages of six to nine were exposed to standardized simulated conflicts involving parents. Results indicate that children’s emotional security, particularly emotional reactivity and internal representations, mediates the relation between marital relations and child adjustment, indicating that one mechanism through which marital discord affects adjustment is via its effects on children’s ER.

Several studies have specifically examined associations between marital conflict/ satisfaction and children’s ER. For example, Volling, McElwain, and Miller (2002) found that a positive marital relationship was associated with siblings’ ability to regulate jealousy in sibling–mother interactions. Similarly, Shaw, Keenan, Vondra, Delliquadri, and Giovannelli (1997) found that parental conflict was associated with children’s internalizing problems and that this relation was amplified among children high in negative emotionality, suggesting that children with dysregulated affect may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of marital discord. In one of the few studies to examine the effects of marital conflict on adolescent ER, Schulz, Waldinger, Hauser, and Allen (2005) found that adolescents who were better able to regulate emotions displayed less hostility and more positive engagement in interactions with high levels of inter-parental hostility. Associations between adolescent hostility and inter-parental hostility decreased with age, suggesting that adolescents are becoming more emotionally independent from their parents as they age.

There is other evidence suggesting that children’s emotion regulatory abilities buffer the negative effects of marital conflict. Katz and Gottman (1995) found that children’s vagal tone, an indicator of parasympathetic activation and ER, moderated the relation between marital hostility and teachers’ reports of children’s behavior problems three years later. Children with low vagal tone (i.e., low parasympathetic activation) who experienced marital hostility at the age of five exhibited externalizing behaviors at the age of eight. In contrast, children with high vagal tone and exposure to marital hostility at the age of five had no behavior problems at the age of eight. Gottman et al. (1997) also found that parents’ awareness of children’s emotions, parents’ emotion coaching, positive parenting and inhibition of parental negative affect all act as a buffer between marital conflict and children’s negative outcomes.

In summary, studies reviewed here suggest that one of the mechanisms through which marital relations affect child adjustment is through children’s emotional security. These results are in line with the work of Fauber, Forehand, Thomas, andWierson (1990) who posit that much of the association between marital conflict and children’s adjustment could be explained by the effects of marital conflict on parenting. Indeed, when examining family factors and children’s ER, researchers must explore links among relationships within the entire family system in order to fully understand the interactive and additive effects on children, and more research on marital relations, and other inter-adult conflict, and ER, specifically, is needed.

Child and Parental Characteristics that Influence the Socialization of Emotion Regulation

As indicated in Figure 1, and described previously, both parent and child characteristics influence processes involved in the socialization of ER. It is not enough to consider socialization as something the parent does to affect the child. Both parents and children bring personal qualities to the relationship, and past socialization experiences set the foundation for later interactions. Parents and children elicit or evoke certain behaviors based on their own characteristics (see Bell & Calkins, 2000), and a brief examination of the ways in which such characteristics influence the socialization of ER follows.

Child Characteristics

In general, research on the impact of the family context on child development stresses the importance of examining the interplay between family factors and child characteristics (Rubin & Mills, 1991; Thomas, 1984). Child characteristics such as temperament, gender and developmental status all play important roles in the effectiveness, and even appropriateness, of socialization practices. Thus, in our model, we posit that child characteristics moderate relations between components of the family context and children’s ER (see Figure 1).

Temperament/Emotional Reactivity

Probably the most important characteristic to consider when examining the socialization of ER is children’s propensity toward experiencing negative emotions, one commonly assessed indicator of child temperament (Kochanska, 1994; Thomas, 1984). Children high in negative reactivity have a tendency to experience high levels of anger, frustration, irritability, nervousness, fear, and sadness; and research indicates that these children are at risk for developing a host of behavioral and emotional problems (Brody, Stoneman, & Burke, 1987; Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, et al., 1996; Eisenberg et al., 1997; Morris et al., 2002; Morris, Silk, et al., 2002; Shields et al., 1994). Calkins (1994) argues that parental socialization of ER depends on children’s negative emotional reactivity, presumed to vary as a function of innate neuroregulatory mechanisms. We believe that emotionally reactive children and adolescents experience more frequent and intense levels of emotional arousal, and as a result will require strong emotion regulatory skills in order to manage such arousal. Thus, highly reactive children and adolescents stand to benefit most from parenting practices related to refining and rehearsing skills for regulating emotions, but also stand to be harmed most by critical and minimizing responses to emotions (see also Goldsmith, Lemery, & Essex, 2004; Rothbart & Bates, 1998). There is growing evidence supporting such claims. For example, Silk, Shaw, Forbes, Lane, and Kovacs (2006) found that positive anticipation of reward during a waiting period was associated with lower levels of internalizing problem behaviors. However, this link was amplified among children of depressed parents, such that reward anticipation was more strongly associated with internalizing problems for children of depressed mothers than for children of never-depressed mothers. Similarly, Morris, Silk, et al. (2002) found that children high in irritable distress displayed more externalizing behaviors in the presence of parental hostility, and more internalizing in the presence of parental psychological control. In a related study, Morris and Silk (2001) found that children with a predisposition toward experiencing negative emotionality were less successful using ER strategies (e.g., attention shifting) to regulate anger when they received a disappointing prize.

Given emerging research suggesting that parenting and child temperament interact to predict adjustment (Rothbart & Bates, 1998), and initial evidence suggesting that parenting and negative emotionality interact to affect ER (Morris, Silk, et al., 2001), there are some methodological issues that must be considered. Firstly, there exists an inherent difficulty in separating emotional reactivity from ER (Campos, Frankel, & Camras, 2004; Kagan, 1994). Indeed, it is difficult to know if a child in a stressful situation is successfully regulating emotion, or if the child is experiencing low arousal and does not need to regulate an absent or weak emotion. Ideally, researchers should attempt to assess emotional arousal and regulation independently (i.e., using physiological measures or questionnaires that attempt to separate reactivity from regulation). However, it can be argued that regardless of whether a child is experiencing emotional dysregulation because of hyperarousal or under-regulation, emotional dysregulation is usually maladaptive and may cause behavioral and emotional problems. Another problem with examining temperament (and children’s behavior in general) and parenting involves directionality of effects (see Bell & Calkins, 2000). It is difficult to know if an emotional child is eliciting negative parenting or vice versa, but research suggests that both child temperament and parenting are important to consider in socio-emotional development and have additive effects on child adjustment over time (see Lengua & Kovacs, 2005).

Gender

Other child characteristics, such as gender, are also likely to affect the impact of the family context on children’s ER. Studies indicate that levels of ER and the socialization of ER are both affected by children’s gender. Girls are typically better regulated than boys, and this may be due to innate differences in reactivity levels (Morris, Silk, et al., 2002), and sex of the parent may impact socialization efforts depending on the sex of the child (e.g., Garside & Klimes-Dougan, 2002; Zeman & Shipman, 1997; Zeman, Penza, Shipman, & Young, 1997).

Indeed, several researchers have found evidence for gender-typic socialization of emotional behaviors. For example, studies suggest that parents preferentially reinforce the display of sadness in girls and anger in boys (Block, 1983; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Fuchs & Thelen, 1988). Parents also appear to socialize more relationship-oriented strategies for regulating emotion among girls and more active and instrumental strategies for regulating emotions among boys (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Hops, 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1995; Sheeber, Davis, & Hops, 2002). Some evidence suggests that parents encourage distraction and problem-solving strategies more for boys than for girls (Eisenberg et al., 1998). Thus, it is important to consider the ways in which parent gender, gender socialization and innate biological differences in reactivity among boys and girls differentially and additively affect the socialization of ER.

Development

An in-depth discussion of the development of ER is beyond the scope of this review (see Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Kopp, 1989 for more extensive reviews); thus, we focus on how socialization of ER is likely to change as children develop, with a focus on the transition into adolescence. Developmental scientists agree that parental attempts to facilitate ER differ with the age of the child (cf., Dix, 1991; Eisenberg et al., 1999). When children are young, parents typically initiate regulation strategies, with self-regulation increasing as children grow older (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002). Indeed, in early childhood, much of the children’s ER occurs through the direct intervention of parents. Parents may attempt to regulate young children’s emotions by physically soothing the child, changing their own facial expression, altering the immediate environment, or gratifying the child’s needs (Kopp, 1989). As children develop increasingly sophisticated cognitive and emotional skills, they gradually become more independent in regulating and managing their own emotions (Kopp, 1989). In parallel, parents’ strategies for assisting children’s ER become more sophisticated as children age. For example, parents of school-aged children may talk directly about emotions, and help children use cognitive strategies to think about emotion-eliciting situations in different ways in order to cope with emotions experienced (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002).

Very little is known about parents’ roles in socializing ER during adolescence. What we do know is that during adolescence there is increased conflict and decreased warmth among adolescents and parents, particularly during early adolescence (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Nevertheless, most adolescents report a good relationship with their parents (Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, & Duckett, 1996; Smetana, 1996; Steinberg, 1990; Steinberg & Silverberg, 1986). Additionally, parents must balance an adolescent’s need for autonomy and supervision. Parental involvement and monitoring of behavior are crucial in preventing antisocial behavior. Autonomy granting is significant in that adolescents are developing a more advanced self-concept (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Given these changes, it is likely that parenting in these domains has a direct impact on adolescents’ ER. Moreover, adolescence is also a key period in the maturation of neural regions in the prefrontal cortex thought to underlie the regulation of emotion; however, these regions do not reach full maturity until late adolescence (Spear, 2000). Thus, developmental shifts in neurological functioning during the transition to adolescence likely have a direct impact on ER abilities (see Calkins & Bell, 1999), and parental socialization of ER may be particularly important during this time. Observational research on autonomy and relatedness in parent–adolescent dyads suggests that adolescents who have difficulty establishing autonomous relationships with parents report higher depressive symptoms, while difficulties maintaining relatedness with parents are linked with externalizing behaviors (Allen, Hauser, Eickholt, & Bell, 1994). Thus, adolescents who remain overly dependent on their parents for assistance in regulating emotions may be at risk for internalizing problems, while adolescents who refuse emotional guidance from their parents may be at risk for externalizing problems. Failure to provide structure and adequate supervision during adolescence, specifically, may affect ER such that increases in behavior problems due to lack of supervision are linked to emotion dysregulation, particularly problems in anger regulation (Frick & Morris, 2004). Moreover, neglectful, uninvolved parenting likely puts adolescents at greatest risk for ER problems as these adolescents have the fewest boundaries and experience the highest levels of adjustment difficulties (Maccoby & Martin, 1983); ER is likely one key component of such problem behavior. However, little research confirms direct links between structure/supervision and ER, despite strong links between these types of parenting behaviors and overall adolescent adjustment (Steinberg & Morris, 2001; Steinberg & Silk, 2002).

Between early and middle adolescence, changes in the social context are believed to result in increased reliance on peers as agents in the ER process and decreased reliance on parents. For example, Zeman and Shipman (1997) found that children’s expectancies for parental involvement in emotion management in response to anger and sadness vignettes changed across adolescence. Early-to-mid adolescents (eighth grade) expected the least interpersonal support from mothers, compared to preadolescents and late adolescents. These changes are consistent with findings that during puberty, children’s relationships with their parents show decreased levels of parent–child cohesion (Steinberg, 1988) and increased parent–child conflict (Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998).

Developmental changes in the socialization of ER are indeed a ripe area for research, particularly research aimed at adolescents. As adolescents develop more advanced coping and ER mechanisms, and begin to deal with more complex stressors (e.g., increased academic demands, romantic relationships), socialization opportunities are abundant. It may be that because of increased conflict during early adolescence parents do not take advantage of such opportunities. This potential emotional distancing could affect parent–adolescent relations and in turn adjustment. Indeed, increased discourse about emotions and how to handle them successfully is potentially an important component of the parent–adolescent relationship; unfortunately, there is very little research on this topic.

Parental Characteristics

Many parental characteristics influence the socialization of ER, including parents’ own attachment styles and family experiences, meta-emotion philosophy, levels of stress and social support, and parental mental health. Most research on parental characteristics affecting children’s ER to date has focused on parents’ mental health, but there is some preliminary evidence suggesting that other parental characteristics, such as parents’ beliefs about emotions, do affect children’s ER.

Mental Health

The socialization of ER has rarely been directly examined among clinically diagnosed parents and their children; however, some relevant research has been conducted on the families of depressed mothers. These findings suggest that mechanisms for socializing ER may be disrupted in families with depressed parents. Firstly, observational studies have shown that depressed mothers display atypical affective interaction patterns with their children (Gotlib & Goodman, 1999). Depressed mothers have been shown to be less responsive to their children’s emotional states, less likely to match their children’s affect, and to display more anger and sadness and less positive affect than non-depressed mothers (e.g. Field, Healy, Goldstein, & Guthertz, 1990; Hops et al., 1987;Weinberg &Tronick, 1998). Secondly, depressed mothers experience their own deficits in ER (Bradley, 2000; Gross & Muñoz, 1995), suggesting that they may not have all of the skills needed to model, teach and reinforce adaptive ways of modulating distress. In support of these speculations, several studies have found evidence for problems in ER among children of depressed mothers (Garber et al., 1991; Radke-Yarrow, Nottelmann, Belmont, & Welsh, 1993; Silk, Shaw, Skuban, et al., 2006). There is little or no research on antisocial parents and the ways in which characteristics of such parents may impact the socialization of ER. However, it is likely that such parents display maladaptive regulatory behaviors in the family context, particularly in regard to anger, and that children model and learn similar regulatory strategies (see Frick & Morris, 2004).

Family History and Beliefs

Parents’ own familial history and their beliefs about emotions and emotional expression affect the ways in which parents interact on an emotional level with their children (Saarni, Campos, Camras, & Witherington, 2006). Thompson (1991, p. 293) has posited a theory of personal emotion: the development of one’s personal understanding of how emotions function and are managed in oneself. He argues that an individual’s personal theory of emotion develops primarily during adolescence in accordance with identity development. These ideas are carried on into adulthood, and parents’ socialization of ER, particularly their responses to children’s emotions, is affected by such beliefs. Similarly, Gottman et al. (1996, 1997) argue that parents’ meta-emotion philosophy, affects interactions with children, specifically emotion-coaching behavior, previously described in the Parenting Practices section. Parents’ meta-emotion philosophy reflects the degree of emotional acceptance and awareness in oneself and in others, and may differ based on the specific emotion in question (e.g., sadness vs. anger). Few studies have empirically examined theories of personal emotions. However, initial evidence is supportive of such ideas. For example, Ramsden and Hubbard (2002) found that parental acceptance of an emotion, examined as one component of parental emotion coaching, was associated with higher levels of ER in children. More research is obviously needed on parental beliefs about emotions and how they relate to the socialization of children’s ER, grounded in such theories as Thompson and Gottman’s. Additionally, intergenerational research on the transmission of ER practices would greatly inform our understanding of the impact of the family context on the development of children’s ER, and would provided a better understanding of how such behaviors and beliefs are passed from one generation to the next.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Although a great deal of research has transpired in the last decade advancing our understanding of the socialization of ER, there are many advances that need to be made before we can fully understand the complex processes involved. As we outline below, we believe that there are several important areas that need further attention.

Firstly, more consensus on how to measure and operationalize ER is needed (see Cole et al., 2004), and the ways in which different measures of ER are associated with one another and contextual factors needs further examination. Issues involving the assessment of ER and emotion socialization are numerous and are beyond the scope of this review (for a review, see Eisenberg et al., 2005). However, researchers must be clear in discussing which components of ER (e.g., ER strategies vs. more general forms of ER) that they are assessing. Attempts to separate reactivity from regulation, effortful ER from more involuntary regulation (see Eisenberg & Morris, 2002), and to discern the regulation of specific emotions, such as sadness and anger rather than general distress reactions, are all worthy goals that should be pursued in future research.

Secondly, future research on associations between ER and the family context needs to be expanded to include a broader emotional system. More research on fathers, siblings, grandparents living in the home, and the family system as a whole is needed in order to fully understand how the family, and not just parents, impacts ER. Additionally, as mentioned previously, research will benefit from examining parents’ values and beliefs associated with emotions and ER, and cultural factors such as display rules, because parental beliefs and culture are both likely to affect parents’ reactions to children’s emotions and the emotional climate of the family (see Cole & Tamang, 1998; Eisenberg & Zhou, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Friedlmeier & Trommsdorff, 1999). Finally, future research also must include an examination of risk factors that affect the family context and emotional development more broadly, such as dangerous neighborhoods, poverty, stress and parental education (Feldman, Eidelman, & Rotenberg, 2004; Raver, 2004). During adolescence, in particular, as an individual’s social context expands, it is important to consider access to recreational opportunities such as media and sports as well as the expanded influence of peers. For example, researchers have begun to identify popular media as potential sources for down or up regulating adolescents’ emotions (Arnett, 1995; Kurdek, 1987; Larson, 1995; Thompson, 1990), and more research in this area is needed.

Thirdly, future research also should focus on understanding the neurobiological mechanisms through which parental socialization may influence ER. For example, an emotionally arousing family climate may lead to increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity which, over the long-term can lead to atrophy in structures in the prefrontal cortex that play a role in ER (Goodman, McEwen, Dolan, Schafer-Kalkhoff, & Adler 2005). Given evidence that frontal regions of the brain thought to be implicated in ER continue to mature throughout adolescence (Giedd, 2004), these regions have the potential for continued plasticity and likely remain sensitive to socialization influences throughout childhood and adolescence. Little is known about how parental socialization of emotion interacts with brain development; however, this is likely to be an exciting area of future research.

In closing, in this review we establish a firm link between family factors and children’s ER. The emotional climate of the family, parenting behaviors related to children’s emotions, and children’s observational learning about emotionality and regulation, all affect children’s regulation and emotional security, which in turn, we expect, impact children’s adjustment (cf., Contreras et al., 2000; Eisenberg, Loyosa, et al., 2001; Volling, McElwain, Notaro, & Herrera, 2002).We argue that by continuing to examine these links and the inter-relations between family and child factors, a greater understanding of the development of prosocial and problem behavior will emerge.

Acknowledgments

Work on this manuscript was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development, and a grant to the first author from the National Institute of Child Development (NICHD) Grant 1R03HD045501.

Contributor Information

Amanda Sheffield Morris, Oklahoma State University.

Jennifer S. Silk, University of Pittsburgh

Laurence Steinberg, Temple University.

Sonya S. Myers, University of New Orleans

Lara Rachel Robinson, University of New Orleans.

References

- Alessandri SM. Play and social behavior in maltreated preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Eickholt C, Bell KL, O’Conno TG. Autonomy and relatedness in family interactions as predictors of expressions of negative adolescent affect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:535–552. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescents’ uses of the media for self-socialization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:519–533. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Tompson M, Hamilton EB, Goldstein MJ, Guthne D. Family expressed emotion, childhood-onset depression, and childhood-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Is expressed emotion a nonspecific correlate of child psychopathology or a specific risk factor for depression? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:129–146. doi: 10.1007/BF02167896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Tompson M, Woo S, Cantwell DP. Is expressed emotion a specific risk factor for depression or a nonspecific correlate of psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:573–583. doi: 10.1023/a:1012237411007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:417–436. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aucoin KJ, Morris AS, Terranova A. The influence of peers on children’s emotion regulation and social functioning. 2007 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs NJ : Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KC, Campos JJ. Perspectives on emotional development: II. A functionalist approach to emotions. In: Osofsky JD, editor. Handbook on infant development. New York: Wiley; 1987. pp. 555–578. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bell KL, Calkins SD. Relationships as inputs and outputs of emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11:160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Cassidy J. Mothers’ self-reported control of their preschool children’s emotional expressiveness: A longitudinal study of associations with infant-mother attachment and children’s emotion regulation. Social Development. 2003;12:477–495. [Google Scholar]

- Block JH. Differential premises arising from differential socialization of the sexes: Some conjectures. Child Development. 1983;54:1335–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development. 2001;72:549–568. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SJ. Affect regulation and the development of psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner EM, Salovey P. Emotion regulation during childhood: Developmental, interpersonal, and individual considerations. In: Salovey P, Sluyter DJ, editors. Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. New York: Basic Books; 1997. pp. 168–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges LJ, Denham SA, Ganiban JM. Definitional issues in emotion regulation research. Child Development. 2004;75:340–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Burke M. Child temperaments, maternal differential behavior, and sibling relationships. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Individual differences in the biological aspects of temperament. In: Bates JE, Wachs TD, editors. Temperament: Individual differences at the interface of biology and behavior, APA science volumes. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1994. pp. 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Bell KL. Developmental transitions as windows to parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1999;10:368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Smith CL, Gill KL, Johnson MC. Maternal interactive style across contexts: Relations to emotional, behavioral, and physiological regulation during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1998;7:350–369. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Campos RG, Barrett KC. Emergent themes in the study of emotional development and emotion regulation. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:394–402. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Frankel CB, Camras L. On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development. 2004;75:377–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Ackerman BP, Izard CE. Emotions and emotion regulation in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn JF, Tronick EZ. Three-month-old infants’ reaction to simulated maternal depression. Child Development. 1983;54:185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. In: Fox NA, editor. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Serial No. 240 ed. Vol. 59. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 73–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Tamang B. Nepali children’s ideas about emotional displays in hypothetical challenges. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:640–646. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Weimer BL, Gentzler AL, Tomich PL. Emotion regulation as a mediator of associations between mother-child attachment and peer relationships in middle childhood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:111–124. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumberland-Li A, Eisenberg N, Champion C, Gershoff E, Fabes RA. The relation of parental emotionality and related dispositional traits to parental expression of emotion and children’s social functioning. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Children and marital conflict: The impact of family dispute and resolution. New York: Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Emotional security as a regulatory process in normal development and the development of psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Exploring children’s emotional security as a mediator of the link between marital relations and child adjustment. Child Development. 1998;69:124–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67:vii–viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Maternal emotional responsiveness and toddlers’ social-emotional competence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:715–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Emotional development in young children. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Blair KA, DeMulder E, Levitas J, Sawyer K, Auerbach-Major S, et al. Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence. Child Development. 2003;74:238–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Mitchell-Copeland J, Strandberg K, Auerbach S, Blair K. Parental contributions to preschoolers’ emotional competence: Direct and indirect effects. Motivation and Emotion. 1997;21:65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptive processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Brown J. Affect expression in the family, children’s understanding of emotions, and their interactions with others. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1994;40:120–137. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, editors. Emotion and its regulation in early development. Vol. 55. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1992. [Google Scholar]