Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study is to understand the long-term course and outcomes of depressive symptoms among older adults in the community by examining trajectories of depressive symptoms over time and identifying profiles of depressive symptoms predicting different trajectories.

Method

We measured depressive symptoms biennially for up to 12 years, using the modified Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (mCESD) scale, in 1260 community-based adults aged 65+ years. We determined latent trajectories of total mCES-D scores over time. We identified symptom profiles based on subgroups of baseline depressive symptoms derived from factor analysis, and examined their associations with the different trajectories.

Results

Six trajectories were identified. Two had one or no depressive symptoms at baseline and flat trajectories during follow-up. Two began with low baseline symptom scores and then diverged; female sex and functional disability were associated with future increases in depressive symptoms. Two trajectories began with high baseline scores but had different slopes: the higher trajectory was associated with medical burden, higher overall baseline score, and higher baseline scores on symptom profiles including low self-esteem, interpersonal difficulties, neurovegetative symptoms, and anhedonia. Mortality was higher among those in the higher trajectories.

Conclusions

In the community at large, those with minimal depressive symptoms are more likely to experience future increases in symptoms if they are women and have functional disability. Among those with higher current symptom levels, depression is more likely to persist over time in individuals who have greater medical burden and specific depressive symptoms.

Introduction

Depressed older adults confront clinicians with a variety of presentations, ranging from full-blown major depressive disorder through varying degrees of subsyndromal depression to isolated depressive symptoms (Beekman et al., 1999; Blazer, 2003). The long-term natural history of major depression has been addressed in the literature albeit largely in studies conducted before the introduction of antidepressant drugs (Anderson, 1936). The expected course is less clear with regard to depressive symptoms, of which the prevalence is as high as 15% in community-based elderly populations (Mulsant and Ganguli, 1999). Depressive symptoms are associated with considerable functional disability, morbidity and mortality (Bruce et al., 1994; Beekman et al., 1997; Lyness et al., 1999; Ganguli et al., 2002; Judd et al., 2002; Mehta et al., 2003; Lenze et al., 2005), and with higher utilization and cost of health services (Unutzer et al., 2002) in older adults. Yet, due to a paucity of data regarding outcomes and predictors over time (Dew et al., 1997; Van Londen et al., 1998; Cole et al., 1999; Unutzer et al., 2002, Beekman et al., 2002), clinicians currently lack prognostic ability with regard to depressive symptoms. An enhanced understanding would enable clinicians to identify high risk groups and target appropriate interventions to prevent chronicity and disability.

We examined trajectories of depressive symptoms over a follow-up period of up to 12 years in a prospective study of a large community-based cohort of older adults. We then examined baseline symptom profiles to determine whether they predicted different subsequent trajectories and mortality.

Methods

Study site and population

The Monongahela Valley Independent Elders Survey (MoVIES) was conducted from 1987 to 2002, in a population with low income and education levels in rural southwestern Pennsylvania, U.S.A. Sampling and recruitment procedures have been detailed previously (Ganguli et al.,1993). Study procedures were approved annually by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Entry criteria were age 65+ years, living in the community at the time of recruitment, fluency in English, and at least 6th grade education (Ganguli et al., 1993). The cohort of 1681 participants comprised 1422 participants randomly selected from the voter registration list and an additional 259 volunteers from the same area, all meeting the same entry criteria (Ganguli et al., 1993). Participants were assessed at study entry (Wave 1) and reassessed in a series of approximately biennial data collection waves. Between Waves 1 and 2, 340 individuals died, relocated, or dropped out. Depression was assessed for the first time at Wave 2 (1989–1991), which served as the baseline for the present analyses. Cohort size at Wave 2 was 1341. Participants with dementia onset prior to the baseline assessment, with incomplete depression data at baseline, and with incomplete cognitive assessments were excluded from these analyses.

Depression assessment

Participants underwent in-home screening including a modified Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (mCES-D; Radloff, 1977; Ganguli et al., 1995). This previously reported modification includes all 20 original CESD items but asks about their presence over most of the preceding week in a yes/no format coded as 1/0, so that the maximum possible score is 20. When treating the score as a categorical variable, we use a threshold reflecting the 10th percentile score on the mCES-D, which is a score of 5, representing the presence of any five symptoms (Ganguli et al., 1995). The mCES-D was administered at all waves beginning with Wave 2. Total mCES-D scores at each wave were subjected to trajectory analysis (see Statistical Methods below). As the primary focus of this study was the epidemiology of dementia, psychiatric screens other than for depression were not administered, and no psychiatric diagnoses were made other than of dementia. Symptom profiles (subgroups of mCES-D items) were identified based on factor structure, and composite scores were created for each profile as described below in Statistical Methods.

Other assessments

The biennial screening assessment included multiple additional variables (Charney et al., 2003), some of which were included in the analyses described below. Participants were tracked between assessments and complete ascertainment of mortality was obtained (Ganguli et al., 2002).

Besides the mCES-D item subgroups, variables compared among the trajectory groups included basic demographics and clinical measurements including cognition as measured by the Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975); total number of prescription drugs being taken regularly, which has been shown to be a robust measure of general morbidity/medical burden (Ganguli et al., 1997); use of antidepressant drugs (Ganguli et al., 1997); inability to independently perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), according to the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) scale (Doble and Fisher, 1998); and mortality (proportion of subjects deceased during follow-up) (Ganguli et al., 2002).

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the cohort at baseline. Principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation was used to examine the factor structure of the mCES-D at baseline, with the Kaiser Criterion (eigenvalues > 1) applied to determine factor loading and thus identify profiles or subgroups of individual symptoms for further analysis. As these subgroups contained unequal numbers of items, composite scores were created for each profile by averaging and z-transforming the scores.

Trajectory analysis (Shea et al., 1992) was used to identify distinct homogeneous trajectories in our data, based on the values of each individual’s total mCES-D score at five assessment points (waves) over a period of up to 12 years. This is a semi-parametric classification method, with individuals assigned to trajectory groups on the basis of their pattern of repeated scores.

We used SAS PROC TRAJ software, available online at http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/bjones/index.html. The trajectory analysis method has two components which it fits simultaneously: a censoring normal mixed model (Kendler et al., 2006) of the total mCES-D score as a polynomial function of time given the group classification, and a latent class model using multinomial logistic regression of the group classification. Based on the Wald test and the optimum Bayesian information criteria (BIC) (Shea et al., 1992), we determined the trend of each trajectory (linear, quadratic or cubic function of time) and the optimum number of trajectory groups to provide the best fit to the data and to be considered in subsequent analyses.

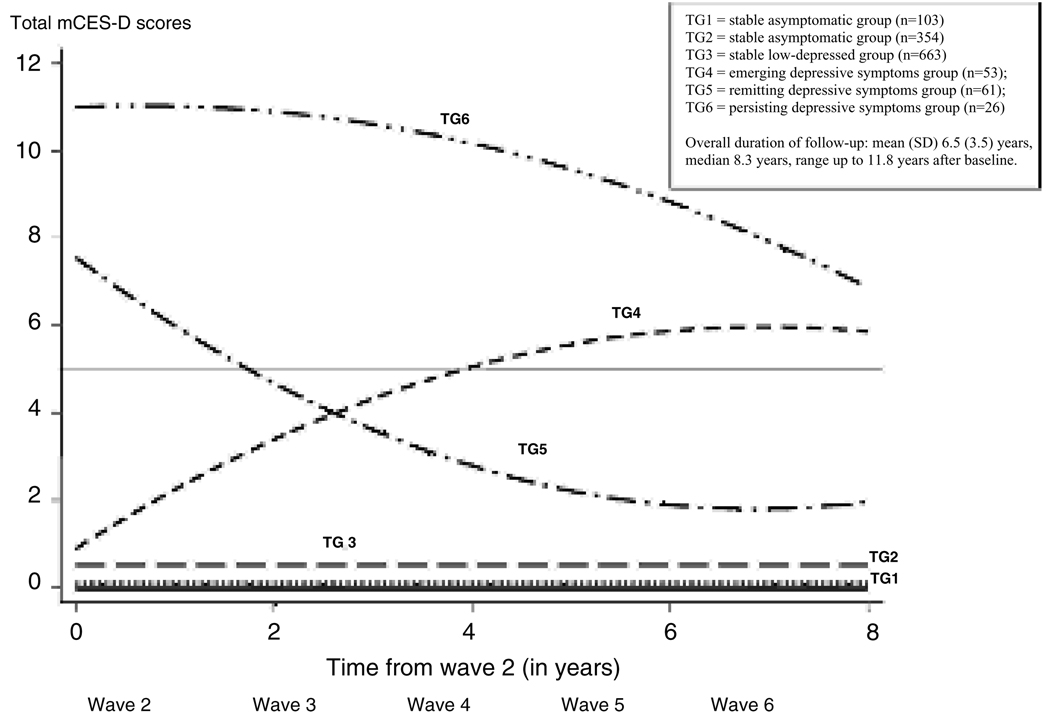

As will be described in the Results section below, the best fit to the data was provided by a model comprising six statistically distinct trajectories (see Figure 1): two trajectories with one or no symptom at baseline, two with low or sub-threshold symptoms (below the 10th percentile score of 5) at baseline, and two with high or supra-threshold symptoms (scores above 5) at baseline. We first used Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables to compare global differences among the six trajectory groups on their baseline characteristics. We selected the low-scoring pair and the high-scoring pair of trajectories for pairwise comparisons. For univariable pairwise comparisons of baseline characteristics and mortality between trajectories, we used nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests for the continuous variables, none of which was normally distributed. We used χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of depressive symptoms

We then used a multiple logistic regression to predict an individual’s trajectory on the basis of his or her baseline characteristics, for the two pairs of groups compared in the univariable analyses. Outcome variables in these models were the different trajectory groups. The main predictor variables were the baseline depressive symptom profiles derived from factor analysis and described below. The covariates included age, sex, education, baseline MMSE score as a measure of cognitive status, any impaired IADLs, and number of prescription medications as a measure of medical burden, as well as recruitment status (random vs. volunteer) at study entry.

Finally, to examine associations of the trajectories with mortality, we fitted a Cox proportional hazards model with time to death as the outcome variable and the trajectory groups as predictor variables, adjusting for age, sex and number of prescription medications (reflecting medical burden) as covariates.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all participants across categories based on depression trajectories over time

| DEPRESSION TRAJECTORY GROUPS |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE SAMPLE SIZE | WHOLE SAMPLE (N = 1,260) |

TG1 (n=103) |

TG2 (n=354) |

TG3 (n=663) |

TG4 (n=53) |

TG5 (n=61) |

TG6 (N =26) |

GLOBAL TEST** |

| Age in years: mean (SD) | 74.6 (5.3) | 72.7 (3.7) | 73.2 (4.5) | 75.4 (5.7) | 76.1 (5.1) | 74.8 (5.4) | 77.6 (5.8) | < 0.001 |

| Women: n (%) | 766 (60.8) | 67 (65.1) | 201 (56.8) | 388 (58.5) | 40 (75.5) | 47 (77.0) | 23 (88.5) | < 0.001 |

| > high school education: n (%) | 770 (61.1) | 74 (71.8) | 257 (72.6) | 381 (57.5) | 21 (39.6) | 28 (45.9) | 9 (34.6) | < 0.001 |

| MMSE: mean (SD) | 27.2 (2.1) | 27.9 (1.7) | 27.7 (1.8) | 26.9 (2.3) | 26.2 (2.2) | 26.8 (2.0) | 25.9 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Any IADL impairment: n (%) | 446 (38.2) | 34 (34.0) | 67 (19.4) | 259 (43.0) | 36 (90.0) | 32 (55.2) | 18 (78.3) | < 0.001 |

| Rx drugs taken: mean (SD) | 2.01 (2.09) | 1.54 (1.77) | 1.40 (1.60) | 2.14 (2.11) | 3.06 (2.45) | 3.05 (2.58) | 4.35 (2.64) | < 0.001 |

| Antidepressant drugs taken: n (%) | 36 (2.86) | 2 (1.94) | 3 (0.85) | 17 (2.56) | 3 (5.66) | 4 (6.56) | 7 (26.92) | < 0.001 |

| Total mCES-D score: mean (SD) | 1.39 (2.57) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.21 (0.59) | 1.22 (1.51) | 1.38 (1.62) | 8.20 (3.40) | 11.20 (2.88) | < 0.001 |

| Core Depressive Symptoms*, normalized: mean (SD) | 0.45 (1.15) | −0.38 (0.00) | −0.36 (0.17) | −0.12 (0.64) | −0.08 (0.78) | 2.66 (1.48) | 3.28 (1.13) | < 0.001 |

| Self-Esteem/Interpersonal Symptoms†, normalized: mean (SD) | 0.04 (0.26) | −0.14 (0.00) | −0.11 (0.45) | −0.06 (0.74) | −0.14 (0.00) | 0.23 (1.33) | 3.20 (4.18) | 0.006 |

| Anhedonia/Neurovegetative Symptoms‡, normalized: mean (SD) | 0.57 (1.08) | −0.53 (0.00) | −0.45 (0.29) | 0.001 (0.85) | 0.14 (0.88) | 2.09 (1.24) | 2.98 (0.92) | < 0.001 |

| Mixed Symptoms§, normalized: mean (SD) | 0.16 (0.47) | −0.34 (0.00) | −0.24 (0.48) | −0.05 (0.84) | 0.02 (0.91) | 1.62 (2.00) | 2.04 (2.20) | < 0.001 |

| Years of follow-up: mean (SD) | 6.5 (3.5) | 9.1 (0.8) | 7.7 (2.6) | 5.6 (3.8) | 6.8 (2.5) | 6.0 (3.9) | 4.3 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Deaths during follow-up: n (%) | 526 (41.8) | 11 (10.7) | 100 (28.3) | 335 (50.5) | 31 (58.5) | 29 (47.5) | 20 (76.9) | < 0.001 |

Core Depressive Symptoms Profile: depressed, not happy, lonely, sad, blues, and crying.

Self-Esteem/Interpersonal Symptoms Profile: others unfriendly, dislike, and feeling like failure.

Anhedonia/Neurovegetative Symptoms Profile: poor appetite, not hopeful, not getting going, everything an effort, not enjoying, and not as good as others.

Mixed Symptoms Profile: bothered, talking less, and trouble keeping mind on activities.

Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous variables; χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables.

At baseline (MoVIES Wave 2), the cohort included 1341 members, 1260 of whom were included in the current analyses after excluding 48 participants with dementia onset prior to the baseline assessment, 21 participants with incomplete mCES-D data at baseline, and 12 participants with incomplete MMSE data.

Overall follow-up of this cohort extended up to 11.8 years after baseline (Wave 2) assessment, with a median of 8.3 years. During this period, 41.7% (n=526) participants died, and 8.5% (n=107) were lost from the cohort for other reasons (dropout, too ill, or relocation). The trajectory analyses included all participants assessed at baseline regardless of how long they were followed subsequently. The mean (SD) interval between consecutive waves was 2.4 (0.3) years. Pearson correlation coefficients between total mCES-D scores were strongest for adjacent waves and became weaker for waves further apart.

Depressive symptoms profiles

In the factor analysis of the mCES-D, a four-factor solution was retained according to the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1). These four factors cumulatively accounted for 55% of the variance of the original matrix. All items included in the four respective factors achieved loading ≥ 0.45. Two items – restless sleep and feeling fearful – failed to load at the specified level. Four factors of mCES-D items based on this factor structure were used to characterize participants’ symptom profiles.

Profile 1 was based on the first factor which accounted for 28% of the variance of the original matrix. These symptoms included feeling depressed, not feeling happy, feeling lonely, feeling sad, not being able to shake off the blues, crying. We designated this profile as Core Mood Symptoms.

Profile 2 was based on the second factor which accounted for 9% of the variance. It included thoughts that others were unfriendly, that others disliked her/him, that life had been a failure. We refer to this profile as Self- Esteem/Interpersonal Symptoms.

Profile 3 was based on the third factor which accounted for 12% of the variance. It included poor appetite, not feeling hopeful, not enjoying life, feeling that one could not get going, feeling everything was an effort, not enjoying life, not feeling just as good as other people. We refer to this profile as Anhedonia/Neurovegetative Symptoms.

Profile 4 was derived from the fourth factor which accounted for 6% of the variance. It included a heterogeneous group of symptoms reflecting concentration (trouble keeping mind on what she/he is doing), withdrawal (talked less than usual) and increased sensitivity (being bothered). We refer to this profile as Mixed Symptoms.

We note that profiles 1 to 3 above – core mood, anhedonia/vegetative symptoms, and self-esteem/interpersonal difficulties – derived from the mCESD, are consistent with those described recently by Shafer (2006) in a metaanalysis of factor analyses of the original CES-D (Radloff, 1977).

Trajectories of depressive symptoms

Trajectory analysis revealed six trajectories of total mCES-D scores over time; trajectories 1 through 3 had linear forms while trajectories 4 through 6 were quadratic (see Figure 1); the BIC showed no improvement in model fit beyond the six-trajectory model. In examining characteristics of the entire sample and of each trajectory group, global tests showed that all selected variables were significantly different among the six trajectory groups (see Table 1). Trajectory groups 1 and 2 (TG1 and TG2), which together included the largest number of participants, reported one or no depressive symptoms at baseline with virtually no change in symptom score during follow-up. They were therefore not included in further comparisons.

Trajectory group 3 vs. trajectory group 4

Trajectory groups 3 and 4 (TG3 and TG4) were selected for the first pairwise comparison because both reported sub-threshold (<5) depressive symptoms at baseline, but TG3 subsequently had a flat trajectory over follow-up while TG4 showed an increase in symptom score over time (see Figure 1). We characterize TG3 as the “stable low-depressed” group and TG4 as the “emerging depressive symptoms” group. In univariable analyses (Table 2), compared to TG3, those with emerging depressive symptoms (TG4) were significantly more likely to be women, with lower levels of education, marginally lower cognitive status, at least one impaired IADL, and to report taking a higher number of prescription drugs at baseline. Although a larger proportion of the TG4 than the TG3 participants died during follow-up, this difference was not statistically significant (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Stable low-depressed trajectory group (TG3) versus emerging depression trajectory group (TG4): baseline characteristics

| DEPRESSION TRAJECTORY GROUPS |

UNIVARIABLE ANALYSES |

MULTIPLE LOGISTIC REGRESSION† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG3* (n=663) |

TG4* (n=53) |

TEST STATISTIC* |

P VALUE | ODDS RATIO (95% CI§) |

P VALUE | |

| Age mean (SD) | 75.4(5.7) | 76.1(5.1) | −1.33 | 0.18 | 0.95(0.89, 1.01) | 0.10 |

| Women: n (%) | 388 (58.5) | 40 (75.5) | − 5.86 | 0.02 | 2.47 (1.12, 5.46) | 0.03 |

| > high school education: n (%) | 381 (57.5) | 21 (39.6) | 6.35 | 0.01 | 0.73 (0.35, 1.52) | 0.40 |

| MMSE mean (SD) | 26.9 (2.3) | 26.2 (2.2) | 2.68 | 0.01 | 0.87 (0.75, 1.01) | 0.08 |

| Rx drugs taken: mean (SD) | 2.14 (2.11) | 3.06 (2.45) | −2.86 | 0.004 | 1.14 (0.99, 1.32) | 0.08 |

| Antidepressant drugs taken: n (%) | 17 (2.56) | 3 (5.66) | 1.73 | 0.18 | - | - |

| Death: n (%) | 335 (50.5) | 31 (58.5) | 1.25 | 0.26 | - | - |

| Total mCES-D score: mean (SD) | 1.22 (1.51) | 1.38 (1.62) | −0.50 | 0.62 | - | - |

| Any IADL impairment: n (%) | 259 (43.0) | 36 (90.0) | 33.4 | <0.001 | 10.9 (3.61, 32.9) | <0.001 |

| Core Depressive Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | −0.12 (0.64) | −0.08 (0.78) | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.77 (0.36, 1.61) | 0.48 |

| Self-Esteem/Interpersonal Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | −0.06 (0.74) | −0.14 (0.00) | 0.86 | 0.39 | -‡ | -‡ |

| Anhedonia/Neurovegetative Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | 0.001 (0.85) | 0.14 (0.88) | −1.37 | 0.17 | 0.91 (0.63, 1.31) | 0.61 |

| Mixed Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | −0.05 (0.84) | 0.02 (0.91) | −0.64 | 0.53 | 1.39 (0.96, 2.01) | 0.08 |

Nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables were used to test the difference between groups.

In addition to the listed variables, the multiple regression was also adjusted for the recruitment status.

This test could not be performed because the Anhedonia/Neurovegetative profile was perfectly associated with TG3 when this normalized profile value >0, i.e. all subjects in TG3 and no subjects in TG4 had symptoms in this profile.

CI stands for confidence interval.

In the multivariable analysis comparing TG3 and TG4, only being female and having at least one IADL impairment at baseline were independently associated with future emerging depression. None of the baseline symptom profiles distinguished between groups TG3 and TG4 (see Table 2).

Trajectory group 5 vs. trajectory group 6

Trajectory groups 5 and 6 (TG5 and TG6) were selected for the second pairwise comparison because they both had relatively high mean total mCESD baseline scores. Both trajectories showed a decrease in symptom count over time but their slopes were different (−1.7 vs. 0.1, p < 0.001; see Figure 1). TG5 will be described as the “remitting depressive symptoms” group and TG6 as the “persisting depressive symptoms” group. In univariable analyses, TG6 participants were significantly older than TG5 participants, but the groups were similar on other demographic variables (Table 3). Also, participants in TG6 had significantly higher baseline mCES-D scores, took significantly more prescription drugs overall, and a higher proportion took antidepressant drugs (see Table 3). With regard to baseline symptom profiles, when compared with TG5, TG6 had higher scores on interpersonal/self esteem and on the anhedonia/neurovegetative profiles. A significantly higher proportion of TG6 than TG5 participants died during follow-up (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Remitting depressive symptoms group (TG5) versus persisting depressive symptoms group (TG6): baseline characteristics

| DEPRESSION TRAJECTORY GROUPS |

UNIVARIABLE ANALYSES |

MULTIPLE LOGISTIC REGRESSION† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG5* (n = 61) |

TG6* (n =26) |

TEST STATISTIC* |

P VALUE | ODDS RATIO (95% CI) |

P VALUE | |

| Age mean (SD) | 74.8(5.4) | 77.6(5.8) | −2.18 | 0.03 | 1.06(0.93,1.21) | 0.36 |

| Women: n (%) | 47(77.0) | 23(88.5) | 1.51 | 0.26 | 5.03 (0.59, 43.0) | 0.14 |

| > high school education: n (%) | 28(45.9) | 9(34.6) | 0.95 | 0.36 | 1.01 (0.17, 5.92) | 0.99 |

| MMSE mean (SD) | 26.8(2.0) | 25.9(3.4) | 1.72 | 0.09 | 0.71 (0.42, 1.19) | 0.19 |

| Rx drugs taken: mean (SD) | 3.05(2.58) | 4.35(2.64) | −2.15 | 0.03 | 1.47 (1.07, 2.00) | 0.02 |

| Antidepressant drugs taken: n (%) | 4(6.56) | 7(26.92) | 6.85 | 0.01 | - | - |

| Death: n (%) | 29(47.5) | 20(76.9) | 6.40 | 0.02 | - | - |

| Total mCES-D score mean (SD) | 8.20(3.40) | 11.20(2.88) | −4.27 | <0.001 | - | - |

| Any IADL impairment: n (%) | 32(55.2) | 18(78.3) | 3.72 | 0.08 | 4.82 (0.73, 31.6) | 0.10 |

| Core Depressive Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | 2.66(1.48) | 3.28(1.13) | −1.91 | 0.06 | 1.58 (0.87, 2.88) | 0.14 |

| Self-Esteem/Interpersonal Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | 0.23(1.33) | 3.20(4.18) | −4.25 | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.03, 2.33) | 0.03 |

| Anhedonia/Neurovegetative Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | 2.09(1.24) | 2.98(0.92) | −3.11 | 0.002 | 2.38 (1.12, 5.08) | 0.03 |

| Mixed Symptoms, normalized: mean (SD) | 1.62(2.00) | 2.04(2.20) | −0.83 | 0.41 | 1.32 (0.91, 1.91) | 0.14 |

Nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables were used to test the difference between groups.

In addition to the listed variables, the multiple regression was also adjusted for the recruitment status.

CI stands for confidence interval.

In the multivariable analyses comparing TG5 and TG6, variables independently associated with the persisting depressive symptoms trajectory were: taking more prescription drugs, having higher scores on the interpersonal/self-esteem difficulties and anhedonia/neurovegetative profiles (see Table 3).

Variables excluded from multivariable models

Two baseline characteristics significant in the univariable analyses were excluded from the multiple regression models. By definition, higher baseline total mCESD scores described the higher trajectories; they were also collinear with the symptom factor scores. Total scores were therefore excluded. Antidepressant use at baseline was excluded from both models because of the very small number of individuals reporting this variable in all trajectory groups (Table 1); although the association between TG6 and antidepressant use was statistically significant, the estimates were unstable with very wide confidence intervals.

Power

Some covariates significant in the univariable analyses were no longer significant in the multiple regression models. To determine whether the loss of significance was due to loss of power after adjusting for covariates, power calculations were performed using PASS 2005 (Hintze, 2005). For the regression model comparing TG3 and TG4, we had 80% power at the 0.05 significance level for all covariates except the MMSE. For the regression model comparing TG5 and TG6, we had 80% power at the 0.05 significance level for all covariates except age and IADL.

Mortality

A Cox proportional hazards model was fitted to predict mortality in the cohort as a function of depressive symptom trajectory. Using TG1 as the reference group, all five higher trajectories (TG2 through TG6) were significantly associated with time to death, after adjusting for age, sex and number of prescription medications (reflecting medical burden). The hazard ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) for TG2 through TG6 were 3.5 (1.9–6.5), 4.1 (2.2–7.6), 4.3 (2.1–8.5), 2.9 (1.3–6.4), and 9.6 (4.4–21.0).

Discussion

In a large, community-based cohort followed for up to 12 years, trajectory analyses revealed six trajectories in the course of depressive symptoms: two asymptomatic trajectories, comprising the majority of participants, two low-symptom trajectories that diverged over time, and two high-symptom trajectories with different slopes over time. These trajectories may be viewed as reflecting the natural history of depressive symptoms in the community.

We focused on the two pairs of trajectories that diverged over time. To shed light on potential risk factors for future increase in depressive symptoms among those who were initially free of substantial symptoms, we compared the stable low-depressed group (TG3) with the group which later developed emerging depressive symptoms (TG4). To identify predictors of chronicity among those who already had substantial depressive symptoms at baseline, we compared the remitting depressive symptoms group (TG5) with the persistent depressive symptoms group (TG6).

Predictors of future emergence of depressive symptoms

Only female sex and functional disability at baseline distinguished those who developed an increase in symptoms over time from those who remained at subthreshold levels, after adjusting for covariates. This finding is congruent with current literature on risk factors for depression in old age (Charney et al., 2003; Cole and Dendukuri, 2003).

Predictors of persistence of depressive symptoms

Those with high overall baseline symptoms who experienced greater persistence of symptoms over time started with a greater medical burden and reported more anhedonia/neurovegetative and self-esteem/interpersonal symptoms at baseline. No other variables were independently associated with either trajectory after adjusting for covariates. The persisting symptoms group was significantly older than the remitting group in the univariable analyses, but the age effect was too small to remain an independent factor in the multivariable analysis.

The persisting symptoms group had more severe baseline depression. It is well established that initial severity of depression (Dew et al., 1997; Judd and Akiskal, 2002; Gildengers et al., 2005; Katon et al., 2006) and a higher number of residual symptoms (Judd and Akiskal, 2002; Katon et al., 2006) are predictors of outcome for major (Dew et al., 1997; Gildengers et al., 2005; Katon et al., 2006) and minor depression (Katon et al., 2006). However, the two groups did not differ significantly on core mood symptoms. Rather, those with worse outcomes (including higher mortality) had significantly more difficulties with self-esteem and interpersonal relationships. These findings can be interpreted as evidence of persistent maladaptive personality traits in chronic depression. Alternatively, they can be regarded as evidence of post-depressive personality changes like pessimism, hostile dependence, increased sensitivity, low self esteem (Akiskal, 2005). The entangled relationship between personality traits and depression (Shea et al., 1992; Mulder et al., 2003) is well documented in the literature, as is the negative impact of personality traits on the evolution of depression (Mulder et al., 2003), especially related to the role of neuroticism in predicting the risk for both lifetime and new onset depression (Kendler et al., 2006). For clinicians, our findings highlight the potentially malignant effect of interpersonal difficulties in the evolution of depression. In these cases, psychotherapeutic techniques might prove more beneficial than repeated pharmacotherapy trials (Paykel et al., 1999; Thase et al., 2001). It is also useful to recognize that treatment may not eliminate completely depressive symptoms, to the extent that residual symptoms represent temperamental attributes.

Among participants with high baseline depressive symptoms, those with a persistent course had more anhedonia and more neurovegetative symptoms at baseline than those whose symptoms remitted earlier. It is notable that core mood symptoms did not distinguish between these two groups. Thus, prominent difficulties related to energy and interest may predict chronicity of overall symptoms and may add to the level of impairment and disability experienced by chronically depressed individuals. Clinicians should be cautious in concluding that the resolution of core mood symptoms (sadness, tearfulness) is evidence that depression itself has remitted.

The persisting depression group, despite having a similar baseline level of core mood symptoms as the remitting depressive symptoms group, experienced the highest medical burden and the highest mortality rate. These findings are consistent with the literature regarding the role of age and medical burden as risk factors for depression in late life (Krishnan et al., 2002; Alexopoulos, 2005) and also the association of depression with increased risk of mortality(Ganguli et al., 2002).

Other literature suggests that older adults are less likely than younger adults to endorse sadness when reporting depression and that depression without sadness is accompanied in the elderly by poor outcomes (Gallo et al., 1999). Thus, it may be important for clinicians to continue periodic proactive screening for depression beyond the standard exploration of sadness. They should also recognize the importance of assessing functional ability (Steffens et al., 2005): in individuals with minimal depressive symptoms at baseline, difficulties with daily activities was the only predictor, other than female sex, of future increase in depressive symptoms (Lenze et al., 2005).

A strength of this epidemiologic study is that it was carried out prospectively over more than a decade in a large representative community-based cohort. However, as a consequence, assessments had to be brief and infrequent. Our data on depression are limited to symptoms, rather than syndromes or disorders, and do not include additional psychiatric variables such as family history which might also predict outcomes over time. Although mortality was one of the outcomes of interest, it also led to a 40% reduction in overall cohort size over the duration of the study, with the greatest impact on the group with the highest depressive symptoms. This led to loss of statistical power to detect potential small effects. Reflecting the racial/ethnic composition of the elderly population of the study region, our study cohort was largely white and did not allow the separate examination of minorities. As a population-based observational study, rather than a clinical study, the number of individuals taking antidepressant medications was very small and our data on the scope and duration of treatment were insufficient to examine effects of treatment on outcome.

Still, to our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the long-term natural history of trajectories of depressive symptoms in a representative community sample of older adults, and to examine depressive symptom profiles as predictors of different trajectories. It therefore makes a contribution to understanding natural history, and may generate hypotheses for further research.

Acknowledgments

The work reported here was supported in part by research grant R01 AG07562 and career development grants K25 DK059928, K24 MH069430, and K24 AG022035 from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors are grateful to Dr. Eric Lenze for valuable suggestions, to Dr. Bobby Jones for valuable assistance with the statistical modeling, to Dr. Hiroko Dodge and Ms. Joni Vander Bilt for assistance with manuscript preparation, and to all MoVIES project personnel and study participants from 1987 to 2002 for their contributions to this work.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration

Benoit H. Mulsant has received research funds or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Corcept Therapeutics, Eli Lilly and Co., Eisai, Fox Learning System, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Ortho Inc., Lundbeck Inc., Janssen and and Pfizer Inc.; he directly owns stock (less than $10,000) in Akzo- Nobel N.V., Alkermes, Inc., AstraZeneca, Biogen Idec, Celsion Corp., Elan Corp., plc, Eli Lilly and Co., Forest Pharmaceuticals, The Immune Response Corporation, and Pfizer Inc.

Description of authors’ roles

All the co-authors made substantial contributions to the design, analysis and interpretation of the data and participated in drafting or revising the manuscript.

References

- Akiskal H. Mood disorders: clinical features. In: Sadock B, Sadock V, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1611–1652. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365:1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Prognosis of the depressions of later life. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1936:559–588. [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Braam AW, Smit JH, Van Tilburg W. Consequences of major and minor depression in later life: a study of disability, well-being and service utilization. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1397–1409. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:307–311. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, et al. The natural history of late-life depression: a 6-year prospective study in the community. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:605–611. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. Journal of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2003;58:249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, Blazer DG. The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1796–1799. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney DS, et al. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:664–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1147–1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MG, Bellavance F, Mansour A. Prognosis of depression in elderly community and primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1182–1189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew MA, et al. Temporal profiles of the course of depression during treatment: predictors of pathways toward recovery in the elderly. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:1016–1024. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble SE, Fisher AG. The dimensionality and validity of the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale. Journal of Outcome Measurement. 1998;2:4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Anthony JC. Sadness in older persons: 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:341–350. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity for dementia of population-based criteria for cognitive impairment: the MoVIES project. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 1993;48:M152–M161. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.m152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, Gilby J, Seaberg E, Belle S. Depressive symptoms and associated factors in a rural elderly population: the MoVIES Project. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1995;3:144–160. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199500320-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, Mulsant B, Richards S, Stoehr G, Mendelsohn A. Antidepressant use over time in a rural older adult population: the MoVIES Project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;45:1501–1503. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Mulsant BH. Rates and predictors of mortality in an aging, rural, community-based cohort: the role of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:1046–1052. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildengers AG, et al. Trajectories of treatment response in late-life depression: psychosocial and clinical correlates. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;25:S8–S13. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000161498.81137.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintze J. NCSS and PASS. Number Cruncher Statistical System. Kaysville, UT: 2005. www.ncss.com. [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The clinical and public health relevance of current research on subthreshold depressive symptoms to elderly patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS. The prevalence, clinical relevance, and public health significance of subthreshold depressions. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;25:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Fan MY, Lin EH, Unutzer J. Depressive symptom deterioration in a large primary care-based elderly cohort. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:246–254. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000196630.57751.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. Personality and major depression: a Swedish longitudinal, population-based twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1113–1120. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan KR, et al. Comorbidity of depression with other medical diseases in the elderly. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:559–588. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, et al. The course of functional decline in older people with persistently elevated depressive symptoms: longitudinal findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:569–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness JM, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z, Caine ED. The importance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients: prevalence and associated functional disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47:647–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Langa KM, Sands L, Whooley MA, Covinsky KE. Additive effects of cognitive function and depressive symptoms on mortality in elderly community-living adults. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2003;58:M461–M467. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.5.m461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder RT, Joyce PR, Luty SE. The relationship of personality disorders to treatment outcome in depressed outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:259–264. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulsant BH, Ganguli M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of depression in late life. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60 (Suppl. 20):9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, et al. Prevention of relapse in residual depression by cognitive therapy: a controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:829–835. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer AB. Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:123–146. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MT, Widiger TA, Klein MH. Comorbidity of personality disorders and depression: implications for treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:857–868. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, et al. Biological and social predictors of long-term geriatric depression outcome. International Psychogeriatrics. 2005;17:41–56. doi: 10.1017/s1041610205000979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Friedman ES, Howland RH. Management of treatment-resistant depression: psychotherapeutic perspectives. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62 (Suppl. 18):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Marmon T, Simon GE, Katon WJ. Depressive symptoms and mortality in a prospective study of 2,558 older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10:521–530. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Londen L, Molenaar RP, Goekoop JG, Zwinderman AH, Rooijmans HG. Three- to 5-year prospective follow-up of outcome in major depression. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:731–735. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]