Abstract

Background

Previous studies suggest β adrenergic receptor (βAR) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with out-of-hospital sudden cardiac death (SCD) and overall mortality, but did not specifically examine risk of ventricular arrhythmias (VA).

Objective

We examined the effects of functional SNPs of β1AR and β2AR on the risk of VA and SCD in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods

β1AR (Ser49Gly, Arg389Gly) and β2AR (Gly16Arg, Gln27Glu) SNPs were genotyped in a case-control study comparing 107 patients with CAD and aborted SCD due to VA to 287 CAD controls and 101 healthy controls. These variants were also examined in the Heart and Estrogen Replacement Study (HERS) cohort of women with CAD followed for SCD (n = 66) and non-fatal VA (NFVA) (n = 33) over 6.8 years.

Results

In the case-control study, no statistically significant association was observed for odds of SCD with any of the SNPs or haplotypes tested. Similarly, HERS revealed null effects for these SNPs and haplotypes in relation to risk of SCD, SCD + NFVA, and all-cause mortality. Point estimates and confidence intervals for risk of SCD associated with β2AR27 were similar in both populations (Glu27 carriers vs. Gln27 homozygotes: adjusted OR 1.23 [95% CI 0.75–2.03, p=0.41] in the case-control study, and adjusted RR 1.18 [95% CI 0.69–2.00, p=0.55] in HERS). These null findings trend in the opposite direction and differ from previous published estimates (p=0.01 and 0.07, respectively).

Conclusion

We did not find an increase in risk of SCD associated with any of these common βAR polymorphisms.

Keywords: sudden cardiac death, ventricular arrhythmias, genetics, beta adrenergic receptors, coronary artery disease

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) remains a major public health problem, accounting for nearly half a million deaths in the U.S. in 1999.1 Nearly 80% of SCD occurs in the setting of coronary artery disease (CAD).2 Ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) is the initiating event in the majority of SCD cases.3 Ejection fraction (EF) remains the only major criterion to stratify patients for risk of SCD and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation, but this strategy alone is insensitive and nonspecific.4 Genetic susceptibility to SCD in the setting of CAD is supported by several epidemiologic studies demonstrating that a family history of SCD is an independent risk factor for SCD and primary VF.5, 6, 7

Sympathetic activation, mediated by the β adrenergic receptors β1AR and β2AR, favors the development of ventricular arrhythmias (VA) and SCD.2, 8–12 Two common nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in each of the single-exon β1AR and β2AR genes are observed: β1AR Ser49Gly and Arg389Gly, and β2AR Gly16Arg and Gln27Glu, the latter two of which are in linkage disequilibrium (LD).13 Carriers of the β1AR Gly49 allele are associated with a better survival in congestive heart failure (CHF)14, while the β1AR Gly389 allele is associated with a lower risk for VT.15 β2AR Gly16Arg and Gln27Glu result in altered receptor downregulation and trafficking in transfected cells.16 Recent evidence also suggests a role of these β2AR SNPs in survival and pharmacogenetic response to β blockers following acute coronary syndrome (ACS)17, and in the risk for out-of-hospital sudden death.18 Both studies found a higher risk associated with the Gln27 homozygous genotype. However, neither study investigated the role of these polymorphisms specifically in the development of VA.

To specifically address these issues, we examined the potential role of these functional β1AR and β2AR variants in the risk of VA and SCD in the setting of CAD in two association studies with distinct study populations. Using a case-control design, we studied a group of patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) who had aborted SCD with documented VA, and compared them to two control groups, one with and one without CAD. In an independent study, we sought to validate our case-control findings in the large Heart and Estrogen Replacement Study (HERS) cohort of postmenopausal women with established CAD who were followed prospectively for SCD, VA, and other cardiac events.

Methods

The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved all protocols. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for DNA isolation and plasma collection.

Study Populations

UCSF SCD Case-Control Study

Consecutive cases of aborted SCD presenting to UCSF Medical Center Emergency Department or inpatient cases of aborted SCD at UCSF Medical Center between January 2000 and June 2006 were screened. Aborted SCD was defined as a cardiac arrest with documented sustained monomorphic VT or VF requiring cardioversion or defibrillation, exclusive of torsades de pointes (drug-induced QT prolongation or otherwise). Because we were interested in the most common phenotype of SCD, that occurring in the setting of CAD, only patients with a history of MI were included in this study. Thirty-one SCD cases occurred in the setting of acute ischemia, while 76 SCD cases occurred in the absence of active ischemia. Thus, SCD cases consisted of 107 patients with aborted SCD and a history of MI.

Two control populations were collected from the UCSF Genomic Resource in Arteriosclerosis, a population-based study of atherosclerotic heart disease.19 In order to specifically address the risk for SCD and VA rather than CAD, a CAD control group was identified from patients presenting to the UCSF Cardiology Service and consisted of individuals with prior MI and documented CAD by coronary angiography (≥70% stenosis in ≥1 major arteries) or revascularization procedures. From a cohort of over 16,000 patients, potential CAD Controls were matched on a group level to the SCD Cases with respect to age at index MI ± 5 years, sex, ethnicity, degree of CAD as defined by revascularization procedure (coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG] > percutaneous transluminal angioplasty [PTCA]/stent), and duration of follow up since index MI. We then randomly selected 300 patients who were considered as CAD controls. Thirteen patients were excluded when they were found to have had SCD, leaving 287 patients who were used as CAD Controls.

As a “supercontrol” group, a non-CAD Control group consisting of healthy individuals without known coronary or other disease in their ninth decade of life was selected from the control arm of the UCSF Genomic Resource in Arteriosclerosis. From a cohort of over 3800 participants, potential non-CAD Controls were matched to cases on a group level with respect to sex and ethnicity. We then randomly selected 107 patients who were considered as non-CAD controls. Six patients were excluded when they were found to have had cardiac deaths, leaving 101 patients who served as non-CAD Controls.

Participants in both control groups were confirmed to have been free of VA, SCD, or implantation of an ICD by searching the UCSF electronic medical record and UCSF ICD database, direct phone interview with participant and/or next of kin, and a search of the National Death Index up to August 2006. Any participant found to have had VA or SCD was excluded.

HERS Cohort SCD Study

HERS methods have been previously described.20, 21 Briefly, participants were postmenopausal women with known stable CAD defined by previous MI, CABG, PCI, or angiographic evidence of ≥ 50% stenosis of ≥ 1 major coronary arteries. Participants in HERS were randomly assigned to 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen plus 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate daily (n=1380) or placebo (n=1383). The HERS randomized controlled trial was conducted over 4.1 years, after which women were observed for an additional 2.7 years on average (HERS II).22 Records of all hospitalizations were reviewed, and an independent morbidity and mortality subcommittee blinded to treatment assignment adjudicated all suspected outcome events, including SCD and non-fatal VA requiring resuscitation (NFVA). SCD outcome was defined as an unexpected, non-traumatic, non-self-inflicted fatality in participants who died within one hour of the onset of terminal symptoms; NFVA was adjudicated as VF and unstable VT that required electrical cardioversion. DNA was collected in 2223 of the 2763 women in the combined HERS I/II cohort following retrospective consent for genetic material.

SNP Selection and Genotyping

Patients were genotyped for β1AR Ser49Gly (rs1801252) and Arg389Gly (rs1801253) and β2AR SNPs Gly16Arg (rs1042713) and Gln27Glu (rs1042714).

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes (Gentra Systems) for the UCSF SCD Case-Control Study. DNA from HERS participants was isolated from stored Pap smear slides using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Genotyping was performed blinded to clinical status; positive and negative controls were included. Three polymorphisms were genotyped by the template-directed dye-terminator incorporation assay with fluorescence polarization detection23, 24 using the AcycloPrimeFP II kit (Perkin-Elmer) and read on the EnVision microplate reader (Perkin-Elmer). PCR conditions and primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Table 1. β1AR Arg389Gly was genotyped using the TaqMan Assay (Applied Biosystems, Assay ID: C_8898494_10) and read on the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (PerkinElmer). When indeterminate readings or discrepancies appeared, plates were repeated or genotyping results were verified by sequencing. Genotyping of HERS participants was performed using the MassArray SNP Genotyping System (Sequenom, Inc.) (primers available upon request). Ninety-nine percent (2199 of 2223) of the HERS participants with available DNA were genotyped. Of these, unambiguous genotypes were determined for 2172 (β1AR49), 2139 (β1AR389), 2134 (β2AR16), and 2129 (β2AR27) participants.

Statistical Analysis

UCSF SCD Case-Control Study

Allele and genotype frequencies were determined by gene counting. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed using the appropriate chi-square test. We used multivariate logistic regression to assess the effects of each SNP on odds of SCD, controlled for all factors on which cases were frequency-matched to controls: sex, race/ethnicity, years since index MI, and degree of CAD.25 We evaluated four genetic models for each SNP: dominant, recessive, log additive, and codominant. We repeated the analyses restricted to Caucasians and compared the odds of SCD according to β2AR haplotypes imputed using Bayesian methods,26 as implemented in the PHASE version 2.1 software package [http://www.stat.washington.edu/stephens/software.html].

HERS Cohort SCD Study

We used unadjusted Cox regression for time to SCD, NFVA, or their composite, including the 4 genetic models. We repeated the analyses adjusting for race/ethnicity, age, current smoking, number of MI, use of β blockers at baseline, CHF, diabetes, and hypertension, as well as stratifying by race/ethnicity and β blocker use. We also examined β2AR haplotype effects.

Comparison with External Estimates

We used Z-tests to compare our log odds and hazard ratio estimates with those from the literature. Variances of the external estimates were computed from confidence intervals.

Results

UCSF SCD Case-Control Study

The vast majority of CAD controls (90.9%) and non-CAD controls (100%) were confirmed to have been free of VA or SCD by direct telephone contact and/or a search of causes of death by National Death Index in August 2006. Characteristics of the patients in the SCD cases and the two control groups are shown in Table 1. SCD cases had a higher prevalence of current smoking as compared to CAD controls. While EF determination was available in a majority of SCD cases (89 of 107) within 1–2 days of SCD, only a minority of CAD controls (89 of 287) had EF available near the time of index MI (1–3 months). Among these cases and CAD controls, mean EF was significantly lower for cases (33 ± 12 vs. 52 ± 14, p< 0.01). Age at index MI was comparable for SCD cases (57.1 ± 14.2) and CAD controls (57.1 ± 12.4); mean age of the non-CAD control group was 83.7 ± 5.5 years. With the exception of ACE-I/ARB, medication use was comparable between SCD cases and CAD controls.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of UCSF SCD Case-Control Study

| Characteristic | All SCD Cases (n= 107) | CAD Controls (n= 287) | P value* | Non-CAD Controls (n= 101) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%)** | 92 (86.0%) | 243 (84.7%) | 0.75 | 90 (89.1%) | 0.50 |

| Ethnicity (%)** | 0.87 | 0.84 | |||

| White | 82 (76.6%) | 213 (74.2%) | 78 (77.2%) | ||

| Black | 5 (4.7%) | 21 (7.3%) | 7 (6.9%) | ||

| Asian | 11 (10.3%) | 33 (11.5%) | 10 (9.9%) | ||

| Hispanic | 6 (5.6%) | 14 (4.9%) | 5 (5.0%) | ||

| Other | 3 (2.8%) | 6 (2.1%) | 1 (1.0%) | ||

| Age at Index MI** | 57.1 ± 14.2 | 57.1 ± 12.4 | 0.96 | N/A | |

| Years of Follow Up since MI** | 14.4 ± 9.0 | 14.5 ± 8.9 | 0.93 | N/A | |

| Revascularization (%)** | |||||

| CABG | 56 (52.3%) | 142 (49.5%) | 0.61 | N/A | |

| Stent | 35 (32.7%) | 71 (24.7%) | 0.29 | N/A | |

| PTCA | 12 (11.2%) | 57 (19.9%) | 0.12 | N/A | |

| Diabetes (%) | 15 (18.1%) | 64 (22.4%) | 0.40 | 12 (12.2%) | 0.27 |

| Current Smoker (%) | 12 (14.6%) | 18 (6.3%) | 0.015 | 4 (4.1%) | 0.013 |

| BMI | 25.9 ± 4.6 | 26.9 ± 5.1 | 0.11 | 25.4 ± 3.3 | 0.50 |

| HTN (%) | 58 (54.2%) | 175 (61.0%) | 0.22 | 0 (0%) | 0.00 |

| Medications | |||||

| β blocker | 72 (67.3%) | 147 (51.2%) | 0.14 | N/A | |

| ACE-I/ARB | 55 (51.4%) | 105 (36.6%) | 0.057 | N/A | |

| Statin | 59 (55.1%) | 166 (57.8%) | 0.60 | N/A | |

| Aspirin | 74 (69.2%) | 201 (70.0%) | 0.95 | N/A |

from t-tests or chi-square tests for comparison with SCD cases

variables matched on a group level between SCD cases and CAD controls

SNP Analysis

Genotype frequencies for each SNP are shown in Table 2. No SNP deviated from Hardy-Weinberg expectations. β2AR Gly16Arg and Gln27Glu were in LD, thus 3 common haplotypes were constructed, H1 (Gly16-Glu27), H2 (Arg16-Gln27), and H3 (Gly16-Gln27). The observed allele and haplotype frequencies differed by ethnicity and were comparable to those for the general US population.13

Table 2.

Allele and Haplotype Frequencies in the UCSF SCD Case Control study

| Allele/Haplotype | SCD Cases (all) n=107 | CAD Controls (all) n=287 | NonCAD Controls (all) n=101 | SCD Cases (Caucasian) n=82 | CAD Controls (Caucasian) n=213 | NonCAD Controls (Caucasian) n=78 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β2AR16 | ||||||

| Gly 16 | 58% | 54.6% | 53.7% | 59.7% | 57.2% | 56.3% |

| Arg 16 | 42% | 45.4% | 46.3% | 40.3% | 42.8% | 43.7% |

| β2AR27 | ||||||

| Gln 27 | 66.3% | 67.7% | 65.3% | 60.1% | 62% | 59.7% |

| Glu 27 | 33.7% | 32.3% | 34.7% | 39.9% | 38% | 40.3% |

| H1 (Gly16, Glu27) | 34.0% | 32.0% | 34.2% | 40.9% | 37.4% | 39.9% |

| H2 (Arg16, Gln27) | 42.0% | 44.9% | 46.7% | 40.3% | 42.1% | 44.2% |

| H3 (Gly16, Gln27) | 24.0% | 23.1% | 19.0% | 18.8% | 20.5% | 15.9% |

| β1AR49 | ||||||

| Ser49 | 89.3% | 86.2% | 86.7% | 91.1% | 86.8% | 86.7% |

| Gly49 | 10.7% | 13.8% | 13.3% | 8.9% | 13.2% | 13.3% |

| β1AR389 | ||||||

| Arg389 | 69.5% | 69.7% | 70.9% | 69.4% | 70.2% | 70.7% |

| Gly389 | 30.5% | 30.3% | 29.1% | 30.6% | 29.8% | 29.3% |

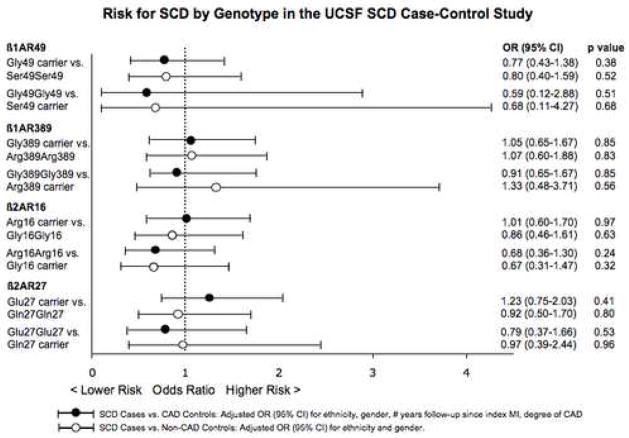

We observed no association between the 4 SNPs and odds of SCD for cases compared to both control groups for all 4 genetic models. Odds ratios for SCD for Case vs. CAD Control and Case vs. Non-CAD Control comparisons for the dominant and recessive models are presented in Figure 1. Analyses adjusted for ethnicity, sex, number of years of follow-up since index MI, and severity of CAD are shown. Analyses restricted to Caucasian individuals or males, also indicated no association between odds of SCD and the 4 SNPs tested (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Among Caucasian individuals, comparison of SCD cases to CAD and non-CAD control groups yielded adjusted ORs for SCD for β2AR Glu27 carriers as compared to Gln27 homozygous individuals of 1.47; (95% CI 0.83–2.61, p=0.18) and 0.97 (95% CI 0.49–1.92, p=0.92), respectively.

Figure 1.

Risk for SCD by Genotype in the UCSF SCD Case-Control Study

Haplotype Analysis

β2AR haplotype analysis for odds of SCD as compared to the CAD control group indicated no association. H2 (Arg16-Gln27) and H3 (Gly16-Gln27) carriers had similar ORs for SCD as compared to reference H1 (Gly16-Glu27) carriers (ORs 1.06, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.82, p=0.844 for H2 and 1.07, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.79, p=0.808 for H3, adjusted for ethnicity, sex, number of years of follow-up since index MI, and severity of CAD). The OR for SCD among those who lack the H1 haplotype was also comparable to reference H1 carriers (0.81, 95% CI 0.49–1.35, p=0.427). Furthermore, diplotype analysis demonstrated no difference for odds of SCD, as compared to individuals with the common diplotype (i.e., H1H2).

HERS Cohort SCD Study

In the combined HERS I/II cohort, 136 of 2763 (4.9%) women suffered SCD over a mean follow-up of 6.8 years and 50 (1.8%) women suffered NFVA. Retrospective consent from relatives could not be obtained for some deceased HERS participants, therefore DNA was available in 66 of 136 SCD cases and 33 of 50 NFVA cases. Of the 2223 participants with DNA, 2125 participants were free of SCD or VA and served as the reference group. No differences were observed in the baseline characteristics between the subset of HERS participants who suffered SCD, SCD+NFVA, and all-cause mortality, compared with the subset of participants that were genotyped (Supplemental Table 4). There was no difference in SCD events between the hormone replacement (E+P) and placebo arms (67 vs. 69, respectively), while there was a statistically significant doubling of NFVA in the E+P arm (33 vs. 17, p=0.02).22

SNP analysis

There were no differences in baseline characteristics by β1AR49, β1AR389, β2AR16, or β2AR27 genotype (Tables 3A and 3B). Allele frequencies for each SNP are shown in Table 4. None of the SNPs deviated from Hardy Weinberg equilibrium. β2AR Gly16Arg and Gln27Glu were in LD, and the 3 common haplotypes described above were constructed. The observed allele and haplotype frequencies differed by ethnicity, and were similar to those obtained in the SCD Case Control study and previous reports.13, 18

Table 3.

| Table 3A: Baseline Characteristics of HERS Subjects by β1AR49 and β1AR389 Genotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

β1AR49 Genotype (N=2172) |

β1AR389 Genotype (N=2139) |

|||||||

| Characteristic | Ser49/Ser49 (N=1641) |

Ser49/Gly49 (N= 477) |

Gly49/Gly49 (N= 54) |

p value | Arg389/Arg389 (N=1124) |

Arg389/Gly389 (N= 827) |

Gly389/Gly389 (N= 188) |

p value |

| Age (years) | 66.4 ± 6.6 | 66.5 ± 6.6 | 67.1 ± 6.2 | 0.73 | 66.6 ± 6.6 | 66.3 ± 6.6 | 66.1 ± 6.4 | 0.36 |

| Race | 0.63 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Caucasian | 1500 (91.4%) | 424 (88.9%) | 46 (85.2%) | 1049 (93.3%) | 732 (88.5%) | 157 (83.5%) | ||

| Afr-Am | 96 (5.9%) | 38 (8.0%) | 6 (11.1%) | 41 (3.7%) | 71 (8.6%) | 27 (14.4%) | ||

| Hispanic | 26 (1.6%) | 9 (1.9%) | 2 (3.7%) | 22 (2.0%) | 12 (1.5%) | 3 (1.6%) | ||

| Other | 19 (1.2%) | 6 (1.3%) | 0 | 12 (1.1%) | 12 (1.5%) | 1 ( 0.5%) | ||

| Diabetes | 357 (21.8%) | 99 (20.8%) | 9 (16.7%) | 0.61 | 237 (21.1%) | 180 (21.8%) | 46 (24.6%) | 0.55 |

| Prior MI | 843 (51.4%) | 234 (49.1%) | 27 (50.0%) | 0.67 | 581 (51.7%) | 422 (51.0%) | 87 (46.3%) | 0.39 |

| Current smoker | 190 (11.6%) | 61 (12.8%) | 8 (14.8%) | 0.62 | 124 (11.0%) | 107 (12.9%) | 23 (12.2%) | 0.43 |

| History of CHF | 191 (11.6%) | 54 (11.3%) | 3 (5.6%) | 0.38 | 121 (10.8%) | 103 (12.5%) | 24 (12.8%) | 0.45 |

| On β blocker at baseline | 538 (32.8%) | 159 (33.3%) | 20 (37.0%) | 0.80 | 382 (34.0%) | 265 (32.0%) | 58 (30.9%) | 0.54 |

| Hypertension | 563 (34.3%) | 160 (33.5%) | 18 (33.3%) | 0.95 | 394 (35.1%) | 284 (34.3%) | 50 (26.6%) | 0.075 |

| Table 3B: Baseline Characteristics of HERS Subjects by β2AR16 and β2AR27 Genotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

β2AR16 Genotype (N=2134) |

β2AR27 Genotype (N=2129) |

|||||||

| Characteristic | Gly16/Gly16 (N= 837) |

Gly16/Arg16 (N= 989) |

Arg16/Arg16 (N= 308) |

p value | Gln27/Gln27 (N= 742) |

Gln27/Glu27 (N=1010) |

Glu27/Glu27 (N= 377) |

p value |

| Age (years) | 66.5 ± 6.7 | 66.5 ± 6.5 | 66.4 ± 6.6 | 0.97 | 66.3 ± 6.6 | 66.4 ± 6.5 | 67.0 ± 6.6 | 0.28 |

| Race | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Caucasian | 779 (93.1%) | 887 (89.7%) | 267 (86.7%) | 624 (84.1%) | 938 (92.9%) | 364 (96.6%) | ||

| Afr-Am | 41 (4.9%) | 74 (7.5%) | 24 (7.8%) | 74 (10.0%) | 58 (5.7%) | 9 (2.4%) | ||

| Hispanic | 12 (1.4%) | 21 (2.1%) | 4 (1.3%) | 23 (3.1%) | 12 (1.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | ||

| Other | 5 (0.6%) | 7 (0.7%) | 13 (4.2%) | 21 (2.8%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | ||

| Diabetes | 166 (19.9%) | 226 (22.9%) | 72 (23.5%) | 0.22 | 164 (22.1%) | 224 (22.2%) | 75 (20.0%) | 0.64 |

| Prior MI | 419 (50.1%) | 505 (51.1%) | 168 (54.6%) | 0.40 | 389 (52.4%) | 509 (50.4%) | 188 (49.9%) | 0.62 |

| Current smoker | 103 (12.3%) | 121 (12.2%) | 37 (12.0%) | 0.99 | 92 (12.4%) | 122 (12.1%) | 44 (11.7%) | 0.94 |

| History of CHF | 89 (10.6%) | 117 (11.8%) | 41 (13.3%) | 0.43 | 88 (11.9%) | 124 (12.3%) | 35 (9.3%) | 0.29 |

| On β blocker at baseline | 275 (32.9%) | 326 (33.0%) | 100 (32.5%) | 0.99 | 245 (33.0%) | 336 (33.3%) | 121 (32.1%) | 0.92 |

| Hypertension | 293 (35.0%) | 335 (33.9%) | 108 (35.1%) | 0.86 | 240 (32.4%) | 349 (34.5%) | 135 (35.8%) | 0.45 |

Table 4.

Allele and Haplotype Frequencies in the Genotyped HERS Cohort:

| Allele/Haplotype | HERS (overall) n=2199 | HERS (Caucasian) n=1994 | HERS (African-Am) n=143 |

|---|---|---|---|

| β2AR16 | |||

| Gly 16 | 62.4% | 63.2% | 56.5% |

| Arg 16 | 37.6% | 36.8% | 43.5% |

| β2AR27 | |||

| Gln27 | 58.6% | 56.7% | 73% |

| Glu27 | 41.4% | 43.2% | 27% |

| H1 (Gly16, Glu27) | 41.4% | 43.4% | 25.7% |

| H2 (Arg16, Gln27) | 37.6% | 36.7% | 43.8% |

| H3 (Gly16, Gln27) | 21.0% | 19.9% | 30.4% |

| β1AR49 | |||

| Ser49 | 86.5% | 86.9% | 82.1% |

| Gly49 | 13.5% | 13.1% | 17.9% |

| β1AR389 | |||

| Arg389 | 71.9% | 73% | 55% |

| Gly389 | 28.1% | 27% | 45% |

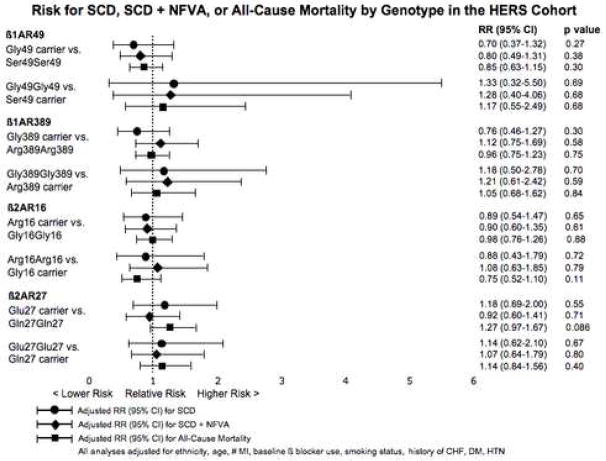

Risk for the outcomes of SCD, SCD + NFVA, and all-cause mortality, were examined for each SNP under the 4 genetic models. The risks for SCD, SCD + NFVA, and all-cause mortality as assessed by the dominant and recessive models for all SNPs tested are shown in Figure 2. Analyses adjusted for ethnicity, age, number of MI, baseline β blocker use, smoking status, CHF, diabetes, and hypertension are presented. Kaplan-Meier analysis of the cumulative incidence of SCD, SCD + NFVA, and all-cause mortality in the HERS cohort by β2AR genotype revealed no suggestion of time-dependent interaction (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

Risk for SCD, SCD + NFVA, and All-Cause Mortality by Genotype in the HERS Cohort

Though no association was observed for risk of SCD or SCD + NFVA, we did observe a trend towards increased risk for all-cause mortality for β2AR Glu27 carriers as compared to Gln27 homozygous individuals (adjusted RR 1.27; 95% CI 0.97–1.67, p=0.086). Analyses restricted to Caucasian participants or stratified by β blocker use at baseline also demonstrated no association for risk of SCD, SCD+ NFVA, or all-cause mortality for any of the SNPs tested (data not shown). Among Caucasian HERS participants, the adjusted RR for all-cause mortality for β2AR Glu27 carriers as compared to Gln27 homozygous individuals was 1.22; 95% CI 0.91–1.63, p=0.175.

Haplotype Analysis

A haplotype analysis for β2AR Gly16Arg and Gln27Glu demonstrated no association for risk of SCD or SCD + NFVA in the HERS cohort. H2 and H3 carriers had similar HRs for SCD and SCD + NFVA as compared to reference H1 carriers (HRs for SCD 0.84, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.41, p=0.50 for H2 and 0.89, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.53, p=0.67 for H3, adjusted for ethnicity, number of MI, baseline β blocker use, smoking status, history of CHF, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension). The HR for SCD among those who lack the H1 haplotype was also comparable to H1 carriers (0.87, 95% CI 0.51–1.49, p=0.61). Analysis by diplotype demonstrated no difference for hazard of SCD or SCD + NFVA by diplotype, as compared to individuals with the common H1H2 diplotype.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate a lack of association between the common functional β1AR and β2AR genetic variants and SCD due to VA in the setting of CAD. Rigorously phenotyped case and control population samples were collected, with documented presence or absence of CAD and VA. The UCSF SCD Case-Control Study findings were replicated in a large cohort of post-menopausal women with documented CAD that was closely followed for adjudicated SCD and VA events.

These nonsynonymous β1AR and β2AR SNPs were chosen as candidates based on their resultant functional changes in receptor activity and the role of the sympathetic system in potentiating the development of VA. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown higher sympathetic activity of the β1AR Arg389 and Ser49 alleles.27 Experiments in human and transfected cell systems demonstrated blunted agonist-mediated receptor downregulation of the β2AR Arg16 and Glu27 variants.28 Sympathetic stimulation and βAR signaling play an important role in both mechanisms for arrhythmogenesis in the setting of CAD captured in our study: primary VF related to acute plaque rupture and ischemia, and scar-mediated VA. Our null results suggest that, while there may be functional differences resulting from these amino acid substitutions, these changes do not result in substantial differences in arrhythmic SCD risk in the setting of CAD.

The β2AR Gln27 homozygous genotype has been linked to both a higher risk for SCD and higher overall mortality among ACS patients discharged on β blocker therapy.17, 18 Sotoodehnia, et. al. reported a higher risk of SCD for Gln27 homozygotes as compared to Glu27 carriers in both an elderly cohort at risk for CAD (adjusted HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.12–2.00 in the Cardiovascular Health Study [CHS]) and a replication study in Caucasians comparing 155 SCD cases to 144 community-based controls (adjusted OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.11–3.04 in the Cardiac Arrest Blood Study [CABS]).18

Our findings for risk of SCD among Gln27 homozygotes vs. Glu27 carriers are inconsistent with the earlier findings. We detected a statistically significant difference in a comparison of the results of the case-control studies, (p=0.01 by Z-test for comparison of results for CABS and the UCSF SCD Case-Control Study, restricted to Caucasians) and a suggestive difference for the comparison of the results of the cohort studies (p=0.07 for comparison of results from CHS and HERS). Moreover, the point estimates in both of the current studies suggest a slightly decreased, rather than significantly increased, risk for SCD for Gln27 homozygotes as compared to Glu27 carriers: for SCD cases vs. CAD controls, adjusted OR 0.81 [95% CI 0.49–1.33], inverted from OR presented in Figure 1; for SCD in the HERS cohort, adjusted RR 0.85 [95% CI 0.50–1.45], inverted from RR presented in Figure 2 (risk estimates inverted since our analyses treated the Gln27 allele – the more common allele – as the reference). The upper bound of the confidence intervals of both of our studies indicate that it is highly unlikely that Gln27 homozygosity is associated with more than a 33–45% increase in SCD risk.

There are several potential explanations for this discrepancy. Because of our approach to selecting participants, a large majority of UCSF SCD cases (103 of 107) survived their cardiac arrest. Thus a “survival effect” of the Glu27 carriers may be operative in our SCD cases. However, very similar point estimates were observed for the “true” SCD outcome as well as the combined outcome of SCD + NFVA (a phenotype similar to the UCSF SCD cases) in our HERS cohort. There were also notable phenotypic differences in study populations due to differences in enrollment criteria. The HERS population was exclusively female and somewhat younger than the CHS population (mean age 66 years vs. 73 years). In the UCSF SCD study, only patients with documented VA as the cause of SCD were included. In the CHS and CABS studies, SCD cases included many out-of-hospital sudden deaths as determined by paramedic and chart records, without restriction to those with VA. Thus, the resulting SCD cases may have been more heterogeneous with asystolic, respiratory, and pulseless electrical activity arrests3 as well as other “sudden” cardiac deaths such as some CHF deaths. Finally, both of the current study populations were selected from individuals with known CAD, rather than from a general population of individuals at risk for CAD. Therefore, some of the SCD cases in CHS and CABS may actually have been unrelated to CAD, and it is possible that the Gln27 homozygous genotype may be related to non-cardiac and/or nonarrhythmic sudden deaths that were counted as out-of-hospital SCD by paramedics.

Our HERS data also indicate a trend toward decreased (rather than increased) mortality for the Gln27 homozygous genotype as compared to Glu27 carriers among postmenopausal women with CAD, adjusted for β blocker use (p=0.086). Stratification among only β blocker users in HERS attenuated this trend (p=0.14). These results are inconsistent with Lanfear, et al’s finding of an increased risk for overall mortality among homozygous Gln27 ACS patients treated with β blockers.17 Perhaps this is due to population differences, ours being entirely female and somewhat older (mean age 66 years vs. mean age 59 years), and with chronic stable CAD.

There are notable limitations to our study. Our confidence intervals do not exclude smaller effect sizes for SCD risk for the SNPs studied, though given the overall magnitude of SCD events they are sufficient to exclude moderate effect sizes. There is also the possibility that we may have missed a significant risk in ethnic and other substrata; however, analyses restricted to Caucasians showed very similar results as compared to those for the overall study. Differences in mean EF between SCD cases and the minority of CAD controls in whom EF was available may be due to differences in timing of EF determination (peri-arrest vs. 1–3 months after MI). We may also have missed an effect of an unexamined genotype in LD with our SNPs. Finally, only 80% of the overall HERS cohort and 50% of HERS participants suffering SCD were available for genetic analyses primarily due to inability to obtain surrogate consent. While this may be a source of potential bias, it is highly unlikely that subjects’ genotypes would be associated with an inability to obtain consent.

The strengths of our study include the rigorously phenotyped and adjudicated SCD cases and outcomes of SCD and NFVA, and the comparison to a background of known CAD in two diverse populations. Different designs by different investigators studying different populations produced null results with similar confidence intervals.

Conclusion

In summary, our results suggest that these functional β1AR and β2AR polymorphisms are not substantial risk factors for SCD associated with CAD. Risk for complex traits such as SCD in the setting of CAD are expected to be the summation of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental effects. As replication of genetic association studies is key, the contrasting findings of this study and prior reports of similar population sizes call into question the role for these common βAR SNPs in the risk of SCD related to CAD. Examination of these SNPs in combination with other candidate gene SNPs and in other populations may clarify this disparity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (KL2 RR024130). We thank Mintu Turakhia, M.D. for assistance with the UCSF SCD Study and Kimberly Lee, M.D. for assistance with the figures.

Financial Support: This research was funded by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (KL2 RR024130).

Glossary of Abbreviations

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- βAR

β adrenergic receptor

- VA

ventricular arrhythmia

- NFVA

nonfatal ventricular arrhythmia

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

- ICD

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- HERS

Heart and Estrogen Replacement Study

- EF

ejection fraction

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- MI

myocardial infarction

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- PTCA

percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- OR

odds ratio

- RR

relative risk

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest for any authors

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, et al. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001 Oct 30;104(18):2158–2163. doi: 10.1161/hc4301.098254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zipes DP, Wellens HJ. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1998 Nov 24;98(21):2334–2351. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayes de Luna A, Coumel P, Leclercq JF. Ambulatory sudden cardiac death: mechanisms of production of fatal arrhythmia on the basis of data from 157 cases. Am Heart J. 1989 Jan;117(1):151–159. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huikuri HV, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ. Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 15;345(20):1473–1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedlander Y, Siscovick DS, Weinmann S, et al. Family history as a risk factor for primary cardiac arrest. Circulation. 1998 Jan 20;97(2):155–160. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jouven X, Desnos M, Guerot C, et al. Predicting sudden death in the population: the Paris Prospective Study I. Circulation. 1999 Apr 20;99(15):1978–1983. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dekker LR, Bezzina CR, Henriques JP, et al. Familial sudden death is an important risk factor for primary ventricular fibrillation: a case-control study in acute myocardial infarction patients. Circulation. 2006 Sep 12;114(11):1140–1145. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.606145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podrid PJ, Fuchs T, Candinas R. Role of the sympathetic nervous system in the genesis of ventricular arrhythmia. Circulation. 1990 Aug;82(2 Suppl):I103–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barron HV, Lesh MD. Autonomic nervous system and sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996 Apr;27(5):1053–1060. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00615-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leor J, Poole WK, Kloner RA. Sudden cardiac death triggered by an earthquake. N Engl J Med. 1996 Feb 15;334(7):413–419. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peckova M, Fahrenbruch CE, Cobb LA, et al. Circadian variations in the occurrence of cardiac arrests: initial and repeat episodes. Circulation. 1998 Jul 7;98(1):31–39. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peckova M, Fahrenbruch CE, Cobb LA, et al. Weekly and seasonal variation in the incidence of cardiac arrests. Am Heart J. 1999 Mar;137(3):512–515. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belfer I, Buzas B, Evans C, et al. Haplotype structure of the beta adrenergic receptor genes in US Caucasians and African Americans. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005 Mar;13(3):341–351. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borjesson M, Magnusson Y, Hjalmarson A, et al. A novel polymorphism in the gene coding for the beta(1)-adrenergic receptor associated with survival in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2000 Nov;21(22):1853–1858. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwai C, Akita H, Shiga N, et al. Suppressive effect of the Gly389 allele of the beta1-adrenergic receptor gene on the occurrence of ventricular tachycardia in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2002 Aug;66(8):723–728. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green SA, Turki J, Innis M, et al. Amino-terminal polymorphisms of the human beta 2-adrenergic receptor impart distinct agonist-promoted regulatory properties. Biochemistry. 1994 Aug 16;33(32):9414–9419. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanfear DE, Jones PG, Marsh S, et al. Beta2-adrenergic receptor genotype and survival among patients receiving beta-blocker therapy after an acute coronary syndrome. Jama. 2005 Sep 28;294(12):1526–1533. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sotoodehnia N, Siscovick DS, Vatta M, et al. Beta2-adrenergic receptor genetic variants and risk of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2006 Apr 18;113(15):1842–1848. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.582833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pullinger CR, Hennessy LK, Chatterton JE, et al. Familial ligand-defective apolipoprotein B. Identification of a new mutation that decreases LDL receptor binding affinity. J Clin Invest. 1995 Mar;95(3):1225–1234. doi: 10.1172/JCI117772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grady D, Applegate W, Bush T, et al. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS): design, methods, and baseline characteristics. Control Clin Trials. 1998 Aug;19(4):314–335. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. Jama. 1998 Aug 19;280(7):605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grady D, Herrington D, Bittner V, et al. Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II) Jama. 2002 Jul 3;288(1):49–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu TM, Kwok PY. Homogeneous primer extension assay with fluorescence polarization detection. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;212:177–187. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-327-5:177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaroff JG, Pawlikowska L, Miss JC, et al. Adrenoceptor polymorphisms and the risk of cardiac injury and dysfunction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2006 Jul;37(7):1680–1685. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226461.52423.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet. 2001 Apr;68(4):978–989. doi: 10.1086/319501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthumala A, Drenos F, Elliott PM, et al. Role of beta adrenergic receptor polymorphisms in heart failure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008 Jan;10(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liggett SB. Molecular and genetic basis of beta2-adrenergic receptor function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999 Aug;104(2 Pt 2):S42–46. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.