Abstract

Background

There are limited data regarding unique clinical or laboratory features associated with advanced clear cell (CC) and mucinous (MU) epithelial ovarian cancers (EOC), particularly the relationship between CA-125 antigen levels and prognosis.

Methods

A retrospective review of seven previously reported Gynecologic Oncology Group phase 3 trials in patients with stage III/IV EOC was conducted. A variety of clinical parameters were examined, including the impact of baseline and changes in the CA-125 level following treatment of CC and MU EOC on progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OC).

Results

Clinical outcomes among patients with advanced CC and MU EOC were significantly worse when compared to other cell types (median PFS: 9.7 v 7.0 v 16.7 months, respectively, p <0.001; and median OS:19.4 v 11.3 v 40.5 months, respectively, p < 0.001). Suboptimal debulking was associated with significantly decreased PFS and OS among both of them. While baseline CA-125 values were lower in CC (median: 154 u/ml) and MU (100 u/ml), compared to other cell types (275 u/ml), this level did not appear to influence outcome among these two specific subtypes of EOC. However, an elevated level of CA-125 at the end of chemotherapy was significantly associated with decreased PFS and OS (p < 0.01 for all).

Conclusion

Surgical debulking status is the most important variable at pre-chemotherapy predictive of prognosis among advanced CC and MU EOC patients. Changes in the CA-125 levels at the end treatment as compared to baseline can serve as valid indicators of progression-free and overall survival, and likely the degree of inherent chemosensitivity.

Keywords: CA-125, Clear Cell, Mucinous Cell and Ovarian Cancer

INTRODUCTION

The serum level of CA-125 is well-established as a highly useful surrogate for monitoring the response to treatment and confirming relapse in women with epithelial ovarian cancer (1–4). However, the literature has focused on the more common ovarian cancer histologies, particularly the serous subtype (5–9).

The prognostic value of CA-125 for clear cell or mucinous ovarian cancers is less certain. Both of these entities are rare in the advanced disease setting, together accounting for approximately 5–8% of all patients in clinical trials (10–18). Unfortunately, survival of these patients has been shown to be poor (17,18). There are also reports that these two histologies are relatively resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapy (19–22), and that the CA-125 antigen may not be secreted in the mucinous cell type (23,24). As a result of these unique clinical features, one may reasonably question whether this prognostic factor identified for the overall epithelial ovarian cancer population actually applies to these two cell types (17,18,25,26).

Studies on clear cell and mucinous ovarian cancers are difficult due to the limited numbers, and realistically require an analysis of the combined experience of several studies. To examine unique clinical features of advanced clear cell and mucinous epithelial ovarian cancers, with a particular focus on the predictive value of serum CA-125 antigen in these settings, a review was conducted of seven Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) phase III clinical trials (10–16). Reported here are the results of that evaluation.

METHODS

The current study consisted of a review of data obtained from seven completed and published phase 3 randomized trials conducted by the GOG (Protocols #111, #114, #132, #152, #158, #162 and #172) involving patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. All cases were at FIGO stage III or IV, without undergoing prior chemotherapy or radiation before enrollment onto the trials, while a majority of patients were treated by standard chemotherapy of six cycles of platinum/paclitaxel as required by protocols. Details regarding eligibility criteria, treatment and outcome for each particular study have been previously published (10–16). All patients provided written informed consent consistent with federal, state and local requirements prior to receiving protocol therapy.

The primary endpoints for all seven studies were progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). PFS was calculated from the date of study enrollment to the date of disease recurrence (confirmed on physical, radiologic or serologic exam), death, or most recent follow-up visit. OS was calculated from the date of study enrollment to the date of death due to any cause or last contact. The tumor cell type was determined by the individual institution and all the pathologic materials were centrally reviewed and confirmed by the GOG Pathology Committee.

CA-125 data which were assayed at each clinical laboratory were collected at baseline and during treatment. The baseline CA-125 was determined prior to chemotherapy and following primary surgical cytoreduction. CA-125 obtained during treatment was measured at the beginning of each treatment cycle. For the present analysis, CA-125 at the end of primary chemotherapy was considered the last measurement of CA-125 level over the treatment period whenever the last measurement was performed.

The baseline patient characteristics evaluated included patient age, GOG performance status (PS), International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, surgical debulking status, and tumor grade. Patients were divided into four groups based on stage and debulking status: stage III optimal microscopic (no gross residual), stage III optimal gross (0.1 – 1.0 cm), stage III suboptimal (> 1.0 cm), and stage IV. Clear cell carcinoma was considered “not graded” because there is no accepted standard grading system for this cell type. PS was defined according to GOG criteria, as: 0=normal activity; 1=symptomatic, fully ambulatory; 2=symptomatic, in bed less than 50% of the time. The type of chemotherapy was not considered in the analysis because the majority (approximately 90%) of patients received platinum-based treatment.

Patient characteristics were compared among clear cell, mucinous and other cell types using Chi-square test for categorical variables (PS, stage/debulking and tumor grade) and Kruskal-Wallis rank test for continuous variables (age and CA-125). The Kaplan-Meier procedure was used to estimate PFS and OS and the group-difference in survival function was compared using log-rank test. All the tests were to assess the null hypotheses that the patient characteristics and clinical outcomes were not different among clear cell, mucinous and other cell types.

The Cox proportional hazards model was employed to assess the association between the clinical and pathological factors, and disease progression and survival. In the multivariate analysis, patients with suboptimal stage III and stage IV were combined due to small number of patients in the latter group. Likewise, GOG PS of 1 and 2 were combined, as were tumor grades 2 or 3. CA-125 was categorized as normal (≤ 35 u/ml) or high (> 35 u/ml), consistent with the definition of CA-125 normalization commonly used in clinical practice. All statistical tests were two-tailed. P <0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

One hundred-nine (3%) patients with clear cell type and 73 (2%) with mucinous cell type were reviewed from a total of 3474 stage III/IV patients with epithelial ovarian cancer enrolled in the seven GOG protocols. The baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes for women with the two histologies are summarized in Table 1, as compared to other cell types.

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes for Advanced Stage Clear Cell and Mucinous Ovarian Cancers and Other Cell Types

| Cell Type |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear Cell N=109 |

Mucinous N=73 |

Others N=3292 |

P 6 | |

| Median age (year) | 54 | 52 | 58 | <0.001 |

| GOG PS (%) 1 | 0.65 | |||

| 0 | 37 | 41 | 38 | |

| 1 | 53 | 53 | 51 | |

| 2 | 10 | 6 | 11 | |

| Stage/debulking (%) 2 | <0.001 | |||

| III-optimal Micro | 39 | 27 | 16 | |

| III-optimal Gross | 21 | 21 | 32 | |

| III-suboptimal | 27 | 34 | 35 | |

| IV | 13 | 18 | 17 | |

| Tumor Grade (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 51 | 8 | ||

| 2 | Not Graded | 38 | 38 | |

| 3 | 11 | 53 | ||

| Median CA-125 (u/ml) 3 | 154 | 100 | 275 | <0.001 |

| Median PFS (month) 4 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 16.7 | <0.001 |

| Median OS (month) 5 | 19.4 | 11.3 | 40.5 | <0.001 |

P value reported as global test of comparison among three groups.

PS: performance status.

III-optimal Micro: stage III without gross tumor residual after debulking; III-optimal Gross: stage III with a tumor residual >0 - ≤1cm after debulking; III-suboptimal: stage III with a tumor residual>1cm after debulking.

CA-125 data available for 101 patients with clear cell, 66 with mucinous, and 1695 with other cell types

PFS: progression-free survival.

OS: overall survival.

Clear cell or mucinous ovarian cancer patients were unique in several features: 1) they were more often diagnosed at earlier age (median age: 54 years for clear cell, 52 years for mucinous vs. 58 years for other cell types); 2) well-differentiated tumor (grade 1) was frequently observed among the mucinous type (51% for mucinous vs. 8% for other cell types); 3) complete resection (without gross disease residual) was more frequently accomplished (39% for clear cell and 27% for mucinous vs. 16% for other cell types); 4) CA-125 level (measured at pre-chemotherapy following surgical debulking) was significantly lower, particularly among the mucinous type (median level: 154 u/ml for clear cell and 100 u/ml for mucinous vs. 275 u/ml for other cell types; elevated CA-125: 87% vs. 74% vs. 93%); and 5) both clear cell and mucinous patients experienced substantially poorer outcomes compared to other cell types. The median PFS was 9.7 months for clear cell, 7.0 months for mucinous and 16.7 months for other cell types, whereas the median OS was 19.4 months, 11.3 months and 40.5 months, respectively. Sixty-one percent (61%) of clear cell patients had disease recurrence and 34% died during the first year of study. The prognosis of mucinous patients was even worse, with 64% showing disease progression and 52% dying by the end of the first year of follow-up, in contrast to other cell types with 33% having disease progression and only 11% dying within the first year of treatment. The survival after disease recurrence was 7.6 months, 4.1 months and 19.0 months respectively, for clear cell, mucinous and other cell types.

The prognostic value of pre-treatment CA-125 for ovarian cancer derived from patients based on standard cisplatin/paclitaxel will be reported elsewhere (27). That analysis included only 37 clear cell and 26 mucinous cell patients. The present analysis involved more patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and focused on assessment of the prognostic value of CA-125 change following treatment among clear cell and mucinous ovarian cancers.

Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer

The most common patient characteristics (age, PS and stage/debulking status) associated with clinical outcomes were assessed first using the Cox regression model. The stage/debulking status were significantly predictive of prognoses. Compared to the stage III/microscopic patients, women with suboptimal stage III or stage IV were at increased risk for disease progression (HR: 3.50, 95% CI: 2.13–5.75) and increased risk for death (HR: 2.71, 95% CI: 1.61–4.57). The prognostic values of age with OS (HR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.03–1.58 for increase of each 10 years) and PS with PFS (HR: 1.50, 95% CI: 0.95–2.37, for PS 1 or PS 2 versus PS 0) were also suggestive (Table 2a).

Table 2.

| a. Multivariate Analyses of Prognostic Factors for Advanced Stage Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Progression |

Death |

|||||

| HR | 95% C.I. | P | HR | 95% C.I. | P | |

| Age (increase 10 yrs) | 1.13 | 0.93 – 1.38 | 0.23 | 1.28 | 1.03 – 1.58 | 0.03 |

| GOG PS 1 | 0.08 | 0.67 | ||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 1.50 | 0.95 – 2.37 | 1.11 | 0.68 – 1.82 | ||

| Stage/debulking 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| III optimal Micro | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| III optimal Gross | 1.25 | 0.70 – 2.24 | 1.43 | 0.77– 2.65 | ||

| III suboptimal/IV | 3.50 | 2.13 – 5.75 | 2.71 | 1.61– 4.57 | ||

| b. CA-125 Levels and Clinical Outcomes for Advanced Stage Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Progression |

Death |

|||||

| HR | 95% C.I. | P | HR | 95% C.I. | P | |

| CA 125 at pre-treatment | ||||||

| High vs. Normal | 1.95 | 0.84 – 4.54 | 0.12 | 1.42 | 0.57 – 3.53 | 0.45 |

| CA 125 at end of treatment | ||||||

| High vs. Normal | 3.34 | 1.96 – 5.68 | <0.001 | 2.41 | 1.39 – 4.19 | 0.002 |

Hazard ratio (HR) estimated from Cox model.

PS: performance status.

III-optimal Micro: stage III without gross tumor residual after debulking; III-optimal Gross: stage III with a tumor residual >0 - ≤1cm after debulking; III-suboptimal: stage III with a tumor residual>1cm after debulking.

CA-125 at pre-chemotherapy or during treatment evaluated separately by Cox regression models, HR estimated adjusted for age, performance status and FIGO stage/volume residual; CA 125 at pre-treatment defined as the measurement at pre-chemotherapy following surgical debulking; CA-125 at end of treatment defined as the last measurement of CA-125 level over treatment period; CA-125≤ 35 u/ml defined as normal and CA-125>35 u/ml defined as high

Pre-chemotherapy CA-125 was available for 101 patients. The median level was 154 u/ml and 13% of patients had a level ≤35 u/ml. The baseline CA-125 level was associated with residual tumor. The median CA-125 was 98, 154 and 225 u/ml, respectively, for stage III-microscopic, stage III optimal, and stage III suboptimal plus stage IV patients. Seventy-seven patients had CA-125 data recorded during the course of treatment. The median level of CA-125 at the end of chemotherapy was 21 u/ml and 65% of individuals achieved a level ≤35 u/ml. In responding patients, the CA-125 antigen decreased with each treatment cycle, with a steep reduction following the first course.

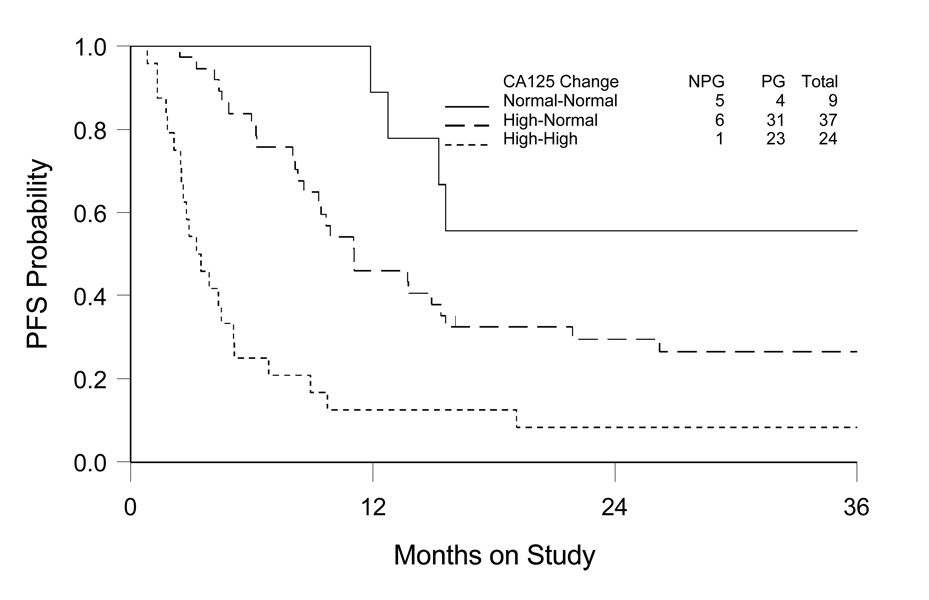

The prognostic value of CA-125 at baseline or during treatment was evaluated separately. The relative risk for disease progression or death for patients >35 u/ml (high) versus ≤35 u/ml (normal) was estimated, adjusted for stage/debulking status, age and PS. As shown in Table 2b, there is a suggestion that CA-125 at baseline was associated with the clinical outcomes (HR: 1.95, 95% CI: 0.84–5.54 for disease progression; and HR: 1.42, 95% CI: 0.57–3.53 for death), although it did not reach the level of being statistically significant. However, there is strong evidence that the CA-125 level at end of treatment was independently predictive of both disease progression (HR: 3.34, 95% CI: 1.96–5.68) and death (HR: 2.41, 95% CI: 1.39–4.19). The estimate of cumulative distribution of PFS based on CA125 change was illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Progression-free Survival (PFS) by Comparing CA-125 Levels at Pre- and End of Chemotherapy for Advanced Stage Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer.

Normal-normal: CA-125 ≤35 u/ml at both pre- and end of chemotherapy; High-normal: CA-125 reduction from >35 u/ml at pre-chemotherapy to ≤35 u/ml at end of chemotherapy; High-high: CA-125 >35 u/ml at both pre- and end of chemotherapy (one patient showing change from ≤35 u/ml to >35 u/ml not included for survival estimate).

NPG: no disease progression; PG: disease progression.

Mucinous Ovarian Cancer

Similarly, the relationships of age, PS, stage/debulking status and tumor grade with clinical outcomes were assessed for patients with mucinous ovarian cancer. Consistent with the data for clear cell type, the stage/debulking status was the most important factor associated with prognoses. Patients with suboptimal stage III or stage IV had a relative risk of 2.28 (95% CI: 1.25–4.15) for disease progression and a relative risk of 2.08 (95% CI: 1.14–3.78) for death compared to stage III/microscopic patients. In contrast to CC patients, the association of age with clinical outcome for MU patients was not statistically significant. Furthermore, there is no evidence that tumor grade was predictive of either PFS (HR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.64–1.72 for grade 2/3 vs. grade 1) or OS (HR: 1.09, 95% CI: 0.66–1.79) (Table 3a).

Table 3.

| a. Multivariate Analyses of Prognostic Factors for Advanced Stage Mucinous Ovarian Cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Progression |

Death |

|||||

| HR | 95% C.I. | P | HR | 95% C.I. | P | |

| Age (increase 10 yr) | 1.14 | 0.96 – 1.36 | 0.15 | 1.10 | 0.92 – 1.31 | 0.30 |

| GOG PS | 0.22 | 0.35 | ||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 1.37 | 0.83 – 2.27 | 1.28 | 0.77 – 2.12 | ||

| Stage/debulking | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||||

| III optimal M | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| III optimal G | 1.60 | 0.78 – 3.31 | 1.35 | 0.65 – 2.82 | ||

| III suboptimal/IV | 2.28 | 1.25 – 4.15 | 2.08 | 1.14 – 3.78 | ||

| TumorGrade | 0.84 | 0.74 | ||||

| 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 2 or 3 | 1.05 | 0.64 – 1.72 | 1.09 | 0.66 – 1.79 | ||

| b. CA-125 Levels and Clinical Outcomes for Advanced Stage Mucinous Ovarian Cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Progression |

Death |

|||||

| HR | 95% C.I. | P value | HR | 95% C.I. | P value | |

| CA 125 at pre-treatment | ||||||

| High vs. Normal | 1.23 | 0.65 – 2.34 | 0.53 | 1.68 | 0.89 – 3.17 | 0.11 |

| CA 125 at end of treatment | ||||||

| High vs. Normal | 5.08 | 2.40 – 0.75 | <0.001 | 2.25 | 1.91 – 5.52 | <0.001 |

Hazard ratio (HR) estimated from Cox model.

PS: performance status.

III-optimal Micro: stage III without gross tumor residual after debulking; III-optimal Gross: stage III with a tumor residual >0 - ≤1cm after debulking; III-suboptimal: stage III with a tumor residual>1cm after debulking.

CA-125 at pre-chemotherapy or during treatment evaluated separately by Cox regression models, HR estimated adjusted for age, performance status and FIGO stage/volume residual; CA 125 at pre-treatment defined as the measurement at pre-chemotherapy following surgical debulking; CA-125 at end of treatment defined as the last measurement of CA-125 level over treatment period; CA-125≤ 35 u/ml defined as normal and CA-125>35 u/ml defined as high

Sixty-six patients had baseline CA-125 data. The median level was 100 u/ml (48, 47 and 154 u/ml, respectively, for stage III-microscopic, stage III optimal, and stage III suboptimal plus stage IV), with 26% of patients having a pre-chemotherapy level ≤ 35 u/ml. The CA-125 data at end of chemotherapy was available for 50 patients, with a median level of 24 u/ml and 62% of individuals having a level ≤35 u/ml.

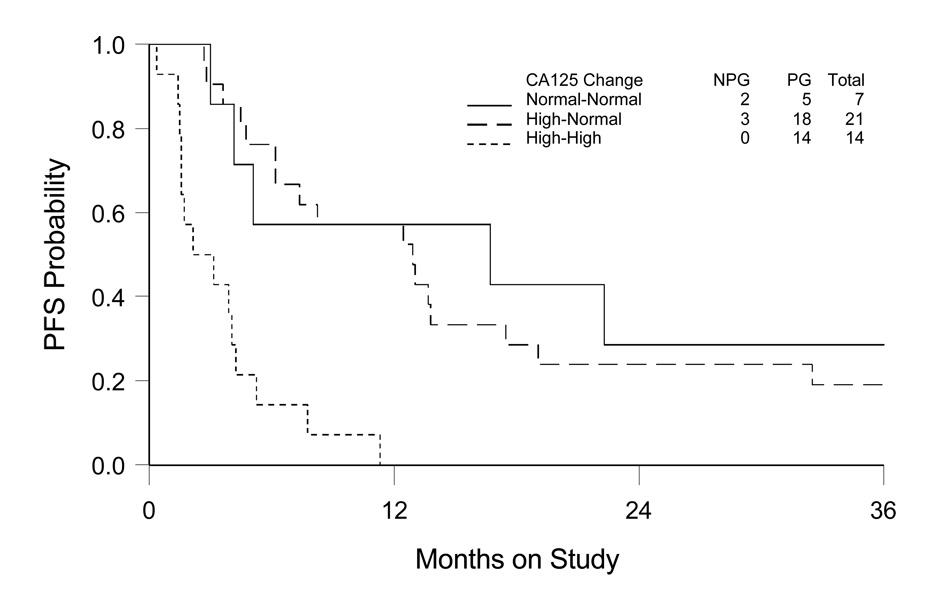

After adjusting for stage/debulking status, age and PS, the CA-125 level at baseline was not significantly related to PFS (HR: 1.23, 95% CI: 0.65–2.34), although showed a trend towards significance with OS (HR: 1.68, 95% CI: 0.89–3.17). However, in contrast to the pre-chemotherapy CA-125, the CA-125 level at the end of treatment was highly associated with both PFS (HR: 5.08, 95% CI: 2.40–10.75) and OS (HR: 2.25, 95% CI: 1.91–5.52) (Table 3b). The estimate of PFS, based on CA-125 change from baseline determination to the end of chemotherapy is shown in Figure 2. The normal-tonormal ( ≤35 u/ml at both time points) and high-to-normal (CA-125 reduced to ≤35 at end of treatment from >35 u/ml at pretreatment) groups demonstrated similar PFS, whereas the high-to-high (>35 u/ml at two time points) patients experienced a much shorter PFS. The data indicate that CA-125 regressing to normal during chemotherapy is a sensitive and significant factor associated with a more favorable prognosis for mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Progression-free Survival (PFS) by Comparing CA-125 Level at Pre- and End of Chemotherapy for Advanced Stage Mucinous Ovarian Cancer.

Normal-normal: CA-125 ≤35 u/ml at both pre- and end of chemotherapy; High-normal: CA-125 reduction from >35 u/ml at pre-chemotherapy to ≤35 u/ml at end of chemotherapy; High-high: CA-125 >35 u/ml at both pre- and end of chemotherapy (two patients showing change from ≤35 u/ml to >35 u/ml not included for survival estimate).

NPG: no disease progression; PG: disease progression.

In summary, stage and tumor residual were the most important prognostic factors for both clear cell and mucinous EOC patients; age was only associated with overall survival for clear cell patients; neither tumor grade nor performance status was significantly associated with clinical outcome; CA125 at pretreatment was less significant in prediction of prognosis; and CA125 following treatment was a valid indicator for monitoring treatment effect among these two specific cell types.

DISCUSSION

This examination of seven large multi-institutional phase 3 GOG trials which included advanced clear cell and mucinous ovarian cancers has confirmed both the rarity of these histologic types (combined 5% incidence in the seven studies involving more than 3,000 total patients), and the poor prognosis associated with these entities (17–22).

As known for other cell types, the stage of disease and the amount of residual cancer are the two most important prognostic factors for patients presenting with either an advanced clear cell or mucinous ovarian cancer. Of interest, in this series, patients with both of these histologies were younger at presentation, compared to the other cell types. Also striking was the lack of association between tumor grade and survival in mucinous ovarian cancer.

A higher percentage of advanced stage mucinous and clear cell ovarian cancer were surgically cytoreduced to microscopic disease, compared to other cell types. Despite this observation, these patients experienced a substantially inferior overall outcome. This fact reinforces the concept of the relative chemoresistance of both clinical entities (19–22).

Data regarding the serum CA-125 levels for patients presenting with advanced clear cell and mucinous ovarian cancers, and their relationship to survival, are also revealing. In both entities, the baseline (pre-chemotherapy) CA-125 antigen levels are lower than other cell types, with median values for clear cell and mucinous cancers being approximately one-half and one third, respectively, compared to all other epithelial ovarian histologies. This observation may result both from the apparent initial smaller volume of disease present following primary surgical cytoreduction as well as fundamental differences in the biology of the malignancies.

However, of particular note, while the baseline CA-125 determinations was less significant in prediction of clinical outcomes, CA-125 regressing to a normal level following treatment was significantly associated with improved PFS and OS in clear cell and mucinous ovarian cancers. This subgroup of patients representing approximately 50% of either clear cell or mucinous ovarian cancers were more likely to benefit from treatment.

Our data also suggest that currently available platinum-based chemotherapy appears to be of only modest benefit in both advanced clear cell and mucinous ovarian cancers as compared to serous and other cell types, although some patients with these histologies and some degree of drug sensitivity may experience a meaningful degree of benefit from such therapy. It is relevant to note that survival in these populations, although generally quite poor, might be considerably worse in the absence of the delivery of platinum-based chemotherapy. New treatment approaches are urgently required in both advanced clear cell and mucinous ovarian cancers.

Although the number of clear cell (n=109) or mucinous cell type (n=73) patients included in the present study is still limited, it is one of the largest studies on advanced clear cell and mucinous epithelial ovarian cancers thus far. All the data were based on phase III clinical trials. Patients received standard surgical treatments and clinical information (clinical parameters, CA125 and outcomes) were prospectively collected in a rigorous manner, although the analysis was done retrospectively. Our data would provide reliable information for understanding these two rare cell types of EOC at an advanced setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are indebted to Mark Brady PhD, for critical review of the manuscript and providing helpful suggestions, and Anne Reardon for assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication.

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants CA 27469 (Gynecologic Oncology Group) and CA 37517 (Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical and Data Center).

All authors meet the criteria for authorship, have approved the final version, and agree to transfer copyright to the Journal of Clinical Oncology should the manuscript be accepted. As stated in the Methods section, patients who were treated provided signed informed consent consistent with all regulatory requirements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rustin GJ, Marples M, Nelstrop AE, et al. Use of CA-125 to define progression of ovarian cancer in patients with persistently elevated levels. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4054–4057. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.20.4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rustin GJ, Timmers P, Nelstrop A, et al. Comparison of CA-125 and standard definitions of progression of ovarian cancer in the intergroup trial of cisplatin and paclitaxel versus cisplatin and cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:45–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridgewater JA, Nelstrop AE, Rustin GJ, et al. Comparison of standard and CA-125 response criteria in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer treated with platinum or paclitaxel. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:501–508. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vergote I, Rustin GJ, Eisenhauer EA, et al. Re: New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors [ovarian cancer]. Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1534–1535. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.18.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vergote IB, Bormer OP, Abeler VM. Evaluation of serum CA 125 levels in the monitoring of ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:88–92. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80352-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makar AP, Kristensen GB, Bormer OP, et al. Serum CA 125 level allows early identification of nonresponders during induction chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;49:73–79. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters-Engl C, Obermair A, Heinzl H, et al. CA 125 regression after two completed cycles of chemotherapy: lack of prediction for long-term survival in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:662–666. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markman M, Liu PY, Rothenberg ML, et al. Pretreatment CA-125 and risk of relapse in advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1454–1458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santillan A, Garg R, Zahurak ML, et al. Risk of epithelial ovarian cancer recurrence in patients with rising serum CA-125 levels within the normal range. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9338–9343. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS, et al. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1001–1007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muggia FM, Braly PS, Brady MF, et al. Phase III randomized study of cisplatin versus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with suboptimal stage III or IV ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:106–115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rose PG, Nerenstone S, Brady MF, et al. Secondary surgical cytoreduction for advanced ovarian carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2489–2497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194–3200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong D, Bundy BN, Walker J, et al. A phase III randomized trial of intravenous paclitaxel and cisplatin versus intravenous paclitaxel, intraperitoneal cisplatin and intraperitoneal paclitaxel in patients with optimal stage III epithelial ovarian carcinoma or primary peritoneal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spriggs DR, Brady MF, Rubin S, et al. A phase III randomized trial of cisplatin and paclitaxel administered by either 24 hour or 96 hour infusion in patients with selected stage III or stage IV epithelial ovarian cancer (GOG162) J Clin Oncol. 2007:4466–4471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3846. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omura GA, Brady MF, Homesley HD, et al. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factor analysis in advanced ovarian carcinoma: the Gynecologic Oncology experience. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1138–1150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.7.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winter WE, Maxwell GL, Tian C, et al. Prognostic factors for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3621–3627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pectasides D, Fountzilas G, Aravantinos G, et al. Advanced stage mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:436–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hess V, A'Hern R, Nasiri N, et al. Mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: a separate entity requiring specific treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1040–1044. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goff BA, Sainz de la CR, Muntz HG, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a distinct histologic type with poor prognosis and resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy in stage III disease. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:412–417. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crotzer DR, Sun CC, Coleman RL, et al. Lack of effective systemic therapy for recurrent clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:404–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu KH, Patterson AP, Wang L, et al. Selection of potential markers for epithelial ovarian cancer with gene expression arrays and recursive descent partition analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3291–3300. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogdall EV, Christensen L, Kjaer SK, et al. CA-125 expression pattern, prognosis and correlation with serum CA-125 in ovarian tumor patients. From The Danish "MALOVA" Ovarian Cancer Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redman JR, Petroni GR, Saigo PE, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1986:515–523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenkop SM, Friedman RL, Wang HJ. Complete cytoreductive surgery is feasible and maximizes survival in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;69:103–108. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zorn KK, Armstrong DK, Tian C, et al. Significance of pretreatment CA-125 level in advanced ovarian carcinoma: A meta-analysis of seven Gynecologic Oncology Group protocols. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104((SGO#3)):S3. [Google Scholar]