Abstract

Regeneration requires specification of the identity of new tissues to be made. Whether this process relies only on intrinsic regulative properties of regenerating tissues or whether wound signaling provides input into tissue repatterning is not known. The head-versus-tail regeneration polarity decision in planarians, which requires Wnt signaling, provides a paradigm to study the process of tissue identity specification during regeneration. The Smed-wntP-1 gene is required for regeneration polarity and is expressed at the posterior pole of intact animals. Surprisingly, wntP-1 was expressed at both anterior- and posterior-facing wounds rapidly after wounding. wntP-1 expression was induced by all types of wounds examined, regardless of whether wounding prompted tail regeneration. Regeneration polarity was found to require new expression of wntP-1. Inhibition of the wntP-2 gene enhanced the polarity phenotype due to wntP-1 inhibition, with new expression of wntP-2 in regeneration occurring subsequent to expression of wntP-1 and localized only to posterior-facing wounds. New expression of wntP-2 required wound-induced wntP-1. Finally, wntP-1 and wntP-2 expression changes occurred even in the absence of neoblast stem cells, which are required for regeneration, suggesting that the role of these genes in polarity is independent of and instructive for tail formation. These data indicate that wound-induced input is involved in resetting the normal polarized features of the body axis during regeneration.

Keywords: anteroposterior axis, β-catenin, planaria

Regeneration is widespread in the animal kingdom but poorly understood (1). Regeneration requires not only new cell formation but also information to specify the identity of tissues to be generated. For example, salamanders and some insects can regenerate missing limbs, which requires proper restoration of a complete proximal–distal axis starting from an injured limb that lacks distal regions (1). Freshwater Hydra can undergo whole-body regeneration of missing structures, which requires that any tissue fragment possess information to replace missing parts (1). Similar properties can be seen in the context of embryonic regulative development. For example, removal of half of the field of cells that become part of the vertebrate limb results in regulative compensation such that a normal limb develops rather than half of a limb (2). The identification of secreted proteins with morphogenic activity in a variety of regenerating systems supports the notion that cell–cell communication influences tissue patterning during regeneration (3–8). Theoretical models have suggested that intrinsic properties of morphogen gradients might be sufficient to account for the reestablishment of complete pattern from tissue fragments during embryonic development or in regeneration (9–12). However, few experimental systems have enabled the study of this problem in regenerating animals.

The phenomenon of regeneration polarity in freshwater planarians provides a paradigm for analyzing in detail the problem of how to specify the identity of missing tissues. Planarians are tribloblastic and a free-living, freshwater member of the phylum Platyhelminthes (13, 14). Planarians can regenerate any type of missing tissue, requiring a pool of adult stem cells called neoblasts and a robust mechanism to specify missing tissue types (15). Regeneration in planarians is accomplished by formation of a regeneration blastema at the wound site and by changes made within preexisting tissues (15). Efficient molecular methods, including RNAi screens, have contributed to the emergence of the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea as a model system for the systematic molecular investigation of regenerative processes (16–19).

When planarians are transected, anterior-facing wounds regenerate a head, and posterior-facing wounds regenerate a tail. This property is known as “regeneration polarity.” Early experiments on polarity performed by T.H. Morgan revealed that thin transverse fragments sometimes incorrectly regenerated a posterior-facing head (20). To explain these data, Morgan proposed that regeneration polarity is controlled by a “gradient of materials” distributed along the anteroposterior axis such that in a thin transverse piece the gradient cannot be interpreted properly (21). How cells located anywhere along the main axis, and therefore possessing existing anteroposterior regional identity, become involved in making either a head or a tail is still a mystery. Recently, RNAi studies have demonstrated that regeneration polarity requires components of canonical Wnt signaling. Inhibition of Smed-β-catenin-1, Smed-Dvl1/2, Smed-Wntless, and Smed-wntP-1 caused animals to regenerate a head rather than a tail at posterior-facing wounds (22–25). Furthermore, knockdown of Smed-APC, which encodes an intracellular inhibitor of β-catenin, caused animals to regenerate a tail from anterior-facing wounds (23). Taken together, these results suggest that regeneration polarity involves a head-versus-tail decision made through some unknown mechanism involving differences in Wnt signaling at anterior- and posterior-facing wounds.

Can intrinsic properties of protein gradients within intact planarians alone account for regeneration polarity? For example, it is possible that properties of Wnt signaling in intact animals endow it with scalable attributes; in this scenario, restoration of the head-to-tail pattern after injury would be due entirely to changes in existing Wnt and Wnt inhibitor gradients as they rescale to accommodate an anteroposterior axis shortened by amputation. We examined the expression and function of Smed-wntP-1 and Smed-wntP-2 in regeneration polarity to determine the mechanism by which Wnt signaling is involved in polarity. Our results indicate that wounding participates directly in the regeneration polarity process by inducing wntP-1 expression.

Results

wntP-1 Is Expressed at Both Anterior- and Posterior-Facing Wounds.

To explore the mechanism by which Wnt signaling controls regeneration polarity, we examined in detail the expression of critical Wnt genes during regeneration. Two transverse amputations were performed to generate three fragments (heads, trunks, and tails), and expression of wntP-1 was examined with in situ hybridizations during regeneration (Fig. 1 A–E). In intact animals, expression of wntP-1, a gene required for regeneration polarity (25), is observed in a small number of cells along the dorsal midline near the posterior pole (Fig. 1A and ref. 22). Surprisingly, wntP-1 expression was observed near both anterior- (Fig. 1 C and E) and posterior-facing wounds (Fig. 1 B and D) at early time points after wounding (6–24 h) in heads, trunks, and tail fragments. This expression was observed in disperse subepidermal cells (Fig. S1) located near both the dorsal and the ventral sides. Between 24 and 48 h of regeneration, the behavior of wntP-1 expression near anterior- and posterior-facing wounds diverged. At posterior-facing wounds, wntP-1 expression persisted and became focused in cells located dorsomedially at the posterior pole (Fig. 1 B and D). In contrast, expression of wntP-1 near anterior-facing wounds was no longer apparent after 48 h of regeneration (Fig. 1 C and E).

Fig. 1.

wntP-1 is expressed at both anterior- and posterior-facing wounds during regeneration. (A–E) wntP-1 in situ hybridizations in intact animals (A) and regenerating head (B), trunk (C and D), and tail fragments (E) at time points (h) after surgery. Brackets, magnified regions at posterior- (B and D) or anterior- (C and E) facing wounds. (F–J) Diagrams depict surgeries. In situ hybridizations with wntP-1 riboprobe at time points after tissue slice (F), hole puncture (G), tissue triangle removal and tail amputation (H), oblique amputation (I), and lateral amputation (J). Anterior, top (A) or left (B–J). (A–E) Dorsal view (A and D, 48 h; B–D, 72 h); other panels, ventral view. (F–J) D, dorsal view; V, ventral view; arrows, regeneration-specific wntP-1 expression. (Scale bars: B–E, 100; A, F–J, 200 μm.) Panels represent ≥4 of 5 animals probed.

wntP-1 Expression Is Induced by General Wounding.

Because initial expression of wntP-1 occurred at both anterior- and posterior-facing wounds, we reasoned that wntP-1 might be induced to be expressed near any wound. To test this hypothesis, we examined wntP-1 expression after numerous types of injuries. wntP-1 expression was detected within 18 h after each of a variety of injuries: tissue slice (Fig. 1F), hole puncture (Fig. 1G), tissue wedge excision and tail amputation (Fig. 1H), oblique amputation (Fig. 1I), and longitudinal amputation (Fig. 1J). Because these paradigms involve different types of regeneration rather than replacement of the anterior or posterior pole, these data suggest that wntP-1 expression is wound-induced. wntP-1 is one of the first identified planarian genes for which general wounding elicits expression. For each type of wounding paradigm, wntP-1 expression was detected only at the posterior pole by 65 h (Fig. 1 F–J). These results indicate that general wounding triggered rapid expression of wntP-1 near the wound site and that at later times in regeneration wntP-1 expression was only present near the prospective posterior pole of the regenerating animal.

wntP-1 Is Involved in Both Polarity and Anteroposterior Patterning.

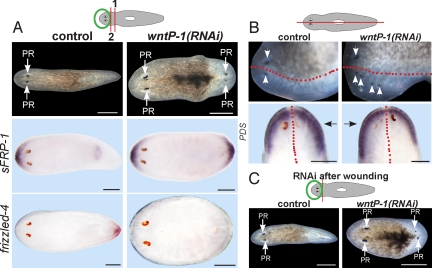

Is wound-induced expression of wntP-1 functionally relevant for polarity in regeneration? To begin to address this question, we examined the phenotype of wntP-1(RNAi) animals after multiple types of amputations. wntP-1(RNAi) head fragments regenerated posterior heads with a modest and reproducible penetrance (20 of 77 animals) (Fig. 2A and ref. 25). dsRNA against Caenorhabditis elegans unc-22, a sequence not present in the S. mediterranea genome, served as the negative control. wntP-1(RNAi) animals with apparent posterior heads expressed an anterior marker in the posterior blastema and lacked posterior marker expression (Fig. 2A). Therefore, wntP-1 is required for posterior identity and regeneration polarity. However, because the observed posterior blastema polarity transformation in wntP-1(RNAi) animals occurs near the site of both wound-induced and posterior-specific wntP-1 expression, it is not clear from this information alone which phase of wntP-1 expression contributes to regeneration polarity.

Fig. 2.

wntP-1 is required for regeneration polarity and anteroposterior patterning. (A) Freshly amputated head fragments (amputation 1) were injected with control or wntP-1 dsRNA for 3 days, amputated again posteriorly on the third day (amputation 2), and allowed to regenerate for 12 days. (Upper) Control head fragments regenerated normally (100%, n = 35), whereas wntP-1(RNAi) animals regenerated a posterior-facing head (26%, n = 77, three experiments). (Lower) In situ hybridizations of control or wntP-1(RNAi) animals at 12 days of regeneration probed with sFRP-1 and frizzled-4 riboprobes. Images are representatives: sFRP-1-stained wntP-1(RNAi), 6 of 24 animals; other panels ≥7 of 7 animals. (B) Intact animals were injected for 2 days and amputated sagittally the following day. (Upper) Uninjected lateral fragments regenerated normally (100%, n = 46), whereas wntP-1(RNAi) fragments regenerated with supernumerary photoreceptors (40%, n = 42) by 10 days. (Lower) in situ hybridizations of laterally regenerating control and wntP-1(RNAi) fragments using a prostaglandin-D synthetase (PDS) riboprobe. Black arrows, newly regenerated side. Extent of PDS in situ hybridization signal was greater on the regenerated side in wntP-1(RNAi) (3 of 5 animals with extra photoreceptors), but not in control animals (7 of 7 animals). Red line, approximate old/new tissue boundary. (C) Day 13 regenerating head fragments that were injected with indicated dsRNAs 1 h after decapitation. Diagrams: RNAi and surgical strategies. PR, photoreceptor. Anterior, left (A, B Upper, C) or top (B Lower). (Scale bars: 200 μm.)

Wound-specific and posterior-specific wntP-1 expression can be decoupled spatially in a lateral regeneration assay in which wound-specific wntP-1 expression can be detected along the entire anteroposterior axis (Fig. 1J). Sagittally amputated β-catenin-1(RNAi) animals regenerate an anteriorized blastema with multiple heads (22, 23). Similarly, wntP-1(RNAi) animals regenerated extra photoreceptors (17 of 42 animals) and possessed expanded anterior marker expression compared with that of the non-regenerated half (Fig. 2B). Thus, wntP-1 activity also is required to prevent anteriorization in a context in which tissue along an entire anteroposterior axis must be formed. Therefore, wntP-1 can be required for tissue patterning at a location distant from its site of expression in the intact animal at the posterior pole. This observation suggests that the wound-induced phase of wntP-1 expression has an anteroposterior patterning role in the context of lateral regeneration but does not exclude the possibility of action at a large distance of the late, posterior-pole-localized expression.

Regeneration Polarity Requires Expression of wntP-1 After Wounding.

To understand the mechanism by which wntP-1 promotes polarity, it is important to determine whether regeneration polarity requires only preexisting WNTP-1 protein or whether new production of WNTP-1 is required after wounding. A requirement for β-catenin-1 in polarity specifically during regeneration has been demonstrated previously by injection of β-catenin-1 dsRNA only after amputation (22). To determine whether there is a requirement for wntP-1 specifically during regeneration, freshly amputated head fragments were administered wntP-1 dsRNA by injection. These fragments regenerated posterior heads (21 of 89 animals, three experiments) (Fig. 2C). In contrast, control RNAi animals never regenerated posterior heads (81 of 81 animals). Therefore, wntP-1 is required during regeneration for polarity in head fragments, indicating the importance of newly expressed WNTP-1 in regeneration.

wntP-2 Acts with wntP-1 to Control Regeneration Polarity.

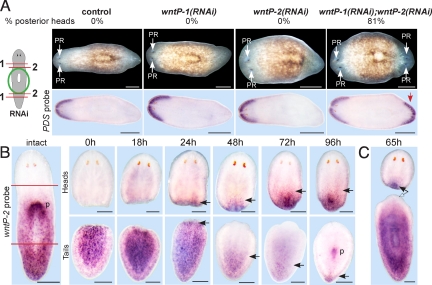

To investigate further the requirements of the wound-induced phase of wntP-1 expression in polarity, identifying functionally relevant target genes was necessary. Several of the nine planarian Wnt genes are expressed in domains along the anteroposterior axis, making them candidates to be such targets (22). To identify Wnt genes that act with wntP-1 to control polarity, we developed an enhancement assay, which took advantage of the fact that wntP-1 inhibition causes only weakly penetrant polarity defects in fragments lacking both heads and tails (“trunks”). An optimized gene inhibition and surgical strategy was developed (Fig. 3A) that revealed a role for the wntP-2 gene in regeneration polarity. Trunk fragments from animals delivered control dsRNA, wntP-1 + control dsRNA, and wntP-2 + control dsRNA all regenerated tails from posterior-facing wounds (40 of 40, 21 of 21, and 32 of 32, respectively) (Fig. 3A). In contrast, wntP-1(RNAi); wntP-2(RNAi) doubly inhibited animals regenerated posterior heads with high penetrance (81%, n = 55) (Fig. 3A). Posterior regeneration blastemas of doubly inhibited animals expressed an anterior marker, whereas singly inhibited and control animals lacked expression of anterior markers in the posterior (Fig. 3A). In an additional test for enhancement, animals delivered wntP-1 + wntP-2 dsRNA had a higher frequency of posterior head regeneration than animals delivered wntP-1 dsRNA + water after a single amputation (11 of 16 versus 1 of 19 animals). Wnt signaling can control polarized aspects of the primary axis in other organisms (8, 26–28); therefore, these data suggest that Wnt signaling in the posterior is a conserved and ancestral feature of bilaterians. We conclude that both wntP-1 and wntP-2 are involved in the polarity decision at posterior wounds.

Fig. 3.

wntP-2 acts with wntP-1 to control regeneration polarity. (A) Diagram depicts RNAi and surgical strategy. Freshly amputated trunk fragments were injected with indicated dsRNA for three consecutive days, amputated near the anterior and posterior wound sites again on the third day, and allowed to regenerate 14 days. wntP-1 and wntP-2 individual injections were mixed with equal amounts of control dsRNA. (Upper) Percentage of animals that regenerated a posterior head. (Lower) In situ hybridizations of regenerating trunk fragments with PDS riboprobe. Red arrow, anterior marker expression in posterior blastema of wntP-1(RNAi); wntP-2(RNAi) double RNAi animals. (B) wntP-2 in situ hybridizations of intact animals and regenerating head and tail fragments at time points (h) after amputation. (B) wntP-2 was detected in an apparent posterior-to-anterior gradient, internally at the anterior pharynx end. New expression of wntP-2 was detected at posterior wounds in regenerating head fragments from 24 h and at progressively anterior locations as regeneration proceeded (p, expression at the new pharynx in a tail fragment). Black arrows, new wntP-2 expression during regeneration (heads) or anterior limit of wntP-2 expression (tails). (C) wntP-2 expression was detected in the posterior of head fragments (solid arrow) but not in the anterior of decapitated fragments at 65 h (empty arrow). PR, photoreceptor. Anterior, left (A) or top (B and C). (Scale bars: 200 μm.)

wntP-2 Is Expressed Subsequently to wntP-1 and at Posterior- Rather Than Anterior-Facing Wounds.

Given the functional requirement of wntP-2 in regeneration polarity, we assessed wntP-2 expression characteristics during regeneration. In intact animals, wntP-2 is expressed broadly in the posterior in an apparent posterior-to-anterior gradient in subepidermal cells located ventrally and dorsally (Fig. 3B and ref. 22). During regeneration, wntP-2 gradually became expressed in the posterior of head fragments in subepidermal cells (Fig. 3B and Fig. S1). Expression was detected as early as 24 h after wounding and expanded with time (Fig. 3B). In tail fragments, wntP-2 expression was initially uniform but became depleted from the anterior with time (Fig. 3B). Because planarian regeneration blastemas alone do not replace all missing tissues during regeneration, planarian regeneration is expected to involve the reestablishment of positional identity along the anteroposterior axis in preexisting tissue (15, 29). Therefore, the progressive loss of wntP-2 in regenerating tail fragments could reflect or instruct axial changes that existing tissues undergo during regeneration. wntP-2 expression was not detected in anterior wounds of decapitated fragments at 24 h (6 of 6 animals) or 65 h (7 of 7 animals) of regeneration (Fig. 3C). Therefore, in contrast to the case for wntP-1, wntP-2 expression does not appear to be induced at all wounds. Furthermore, new expression of wntP-2 at posterior-facing wounds (after 18 h) occurs subsequent to new expression of wntP-1 (before 6 h). Taken together, wntP-2 expression occurs only at posterior-facing wounds and reflects the reestablishment of anteroposterior positional identity that accompanies regeneration from transverse wounds.

Wound-Induced wntP-1 Expression Is β-catenin-1-Independent.

To understand the functional relationship among the genes required for polarity, we began by asking whether β-catenin-1 was required for wound- or posterior-specific wntP-1 expression in regeneration. Because β-catenin can transduce Wnt signals (30), this experiment can help to clarify whether wound signals that induce early wntP-1 expression involve Wnt signaling. Animals were administered either control or β-catenin-1 dsRNA 4 days before surgical removal of heads and tails and then probed for wntP-1 expression by in situ hybridization. wntP-1 expression was detected at anterior and posterior wounds in 18, 36, and 42-h fragments in both control and β-catenin-1(RNAi) animals (Fig. 4A). In contrast, expression of wntP-1 was not detected in posterior blastemas from 72-h β-catenin-1(RNAi) head and trunk fragments (Fig. 4A and Fig. S2). Together, these results indicate that some wound signal, other than Wnts acting through β-catenin-1, induces initial expression of wntP-1 in regeneration.

Fig. 4.

wntP-2 expression at posterior-facing wounds requires wntP-1. In situ hybridizations with wntP-1 (A) or wntP-2 (B) riboprobes of regenerating head fragments at time points (h), which received control, wntP-1, or β-catenin-1 dsRNA before decapitation. For the 36-h time point, freshly amputated head fragments were injected with dsRNA on two consecutive days, amputated posteriorly the following day, and fixed 36 h later. This strategy resulted in 26% penetrance of posterior head regeneration for wntP-1 inhibition (Fig. 2A). For 0, 18, 42, and 72 h time points, intact animals were injected with dsRNA 48 and 24 h before decapitation, and fixation occurred at the indicated times. This RNAi strategy did not result in regeneration of posterior heads for wntP-1 inhibition (10 of 10 animals) but was sufficient to perturb wntP-2 expression (B). (B) (Left) 0 h control, 0 h wntP-1(RNAi), and 18 h β-catenin-1(RNAi). (Lower Left) Scoring (number similar to that shown in the panel versus total number of animals). wntP-2 expression was absent (3 of 5, 36 h; 4 of 7 42 h; 5 of 7 72 h) or much less abundant than control RNAi (2 of 5, 36 h; 3 of 7, 42 h; 2 of 7, 72 h) after wntP-1 RNAi. Arrows indicate new wntP-1 or wntP-2 expression due to regeneration. Anterior, left. Dorsal view (A, 72 h; B, 0, 18, 72 h); all other panels, ventral view. (Scale bars: 200 μm.)

Wound-Induced wntP-1 Activates wntP-2 at Posterior-Facing Wounds.

The expression order of wntP-1 and wntP-2 at posterior-facing wounds raised the possibility that wntP-2 could be a functionally relevant wntP-1 target. Significantly, the identification of such a target could allow the investigation of whether the wound-induced phase of wntP-1 expression is required for polarity. Knockdown of β-catenin-1 or wntP-1 caused a failure in wntP-2 expression in head fragments at 36, 42, and 72 h of regeneration (Fig. 4B). wntP-1(RNAi) head fragments failed to express abundant wntP-2 at days 5 and 8 of regeneration as well (100% of animals, n = 6), suggesting that wntP-1(RNAi) does not simply cause a delay in wntP-2 expression. A failure to detect wntP-2 expression in wntP-1(RNAi) head fragments is unlikely due to a secondary effect of blastema polarity reversal, because wntP-1(RNAi) head fragments that did not regenerate posterior-facing heads also failed to express wntP-2 (Fig. 4B). Because wntP-1 or β-catenin-1 (beta)-catenin-1 RNAi results in failure to express wntP-2, these data indicate that Wnt signaling activates wntP-2 at posterior-facing wounds. Additionally, ectopic β-catenin activity generated by inhibition of the Wnt-inhibitory APC gene resulted in ectopic wntP-2 expression near anterior-facing wounds (Fig. S3). In contrast, a requirement for newly expressed wntP-2 could not be detected for either wound- or posterior-specific wntP-1 expression (Fig. S4). These data suggest that wntP-1 acts through β-catenin-1 to activate wntP-2 expression in regenerating head fragments. Whether this reflects direct or indirect regulation of the wntP-2 gene is unknown. The fact that detectable wntP-2 expression was not always fully eliminated in wntP-1(RNAi) head fragments, but sometimes only reduced, could explain why RNAi of wntP-2 enhances the two-headed regeneration phenotype caused by RNAi of wntP-1. Alternatively, there could be some redundancy in the function of wntP-1 and wntP-2, or a role for preexisting WNTP-1 or WNTP-2 proteins, that explains the enhancement observed after inhibition of both genes. Because wntP-2 expression requires wntP-1 and β-catenin-1 during the wound-induced phase of wntP-1 expression (Fig. 4A), we conclude that wound-induced wntP-1 activates wntP-2 at posterior-facing wounds.

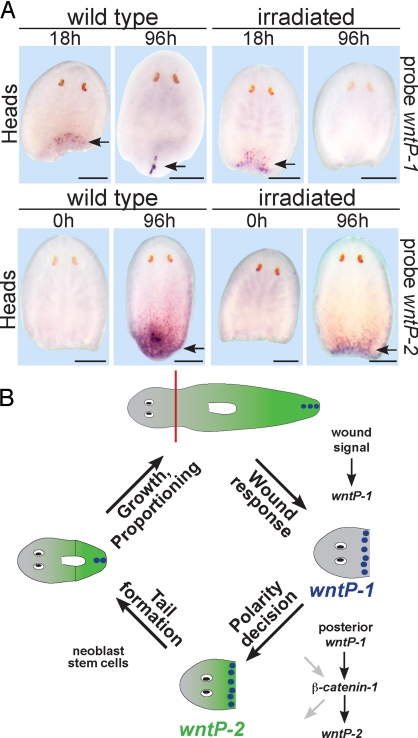

wntP-1 and wntP-2 Expression Occurs Independently of Neoblast Stem Cells.

Are wntP-1 and wntP-2 involved in promoting the decision to regenerate a tail or are they reexpressed as a consequence of tail formation and only involved in implementing the tail formation process? Regeneration of heads and tails completely requires stem cells termed neoblasts (15, 16). We therefore sought to determine whether expression of wntP-1 and wntP-2 in regeneration occurs in animals lacking stem cells that cannot regenerate tails. Irradiation largely specifically eliminates neoblasts (16, 31–33) and therefore can be used to ask whether a process of interest requires neoblasts.

Early, wound-induced expression of wntP-1 in head, trunk, and tail fragments was unaffected by irradiation (Fig. 5A and Fig. S5). Similarly, wntP-2 was expressed in the posterior of irradiated head fragments, and the wntP-2 expression domain contracted posteriorly in irradiated tail fragments (Fig. 5A and Fig. S5). In contrast, wntP-1 expression at late time points could not be detected near the posterior pole of irradiated fragments, indicating that late wntP-1 expression in regeneration requires neoblasts or regenerative outgrowth (Fig. 5A and Fig. S5). Control experiments verified that irradiated animals used in these experiments lacked mitotic cells (Fig. S5). We conclude that wound-induced wntP-1 expression and wntP-2 expression during regeneration occur in cells that are not neoblasts and occur independently of neoblasts and tail formation. Therefore, early wntP-1 and wntP-2 expression changes in regeneration likely instruct tail formation by neoblasts, as opposed to expression occurring as a consequence of tail formation. Tissue patterning during Hydra regeneration (34) or in dorsoventral planarian regeneration (3) does not require proliferation, raising the possibility that mechanisms used to control axial or regional identity in development and regeneration might in general occur independently of proliferation or growth.

Fig. 5.

Dynamic Wnt expression is stem-cell-independent. (A) In situ hybridizations of wntP-1 and wntP-2 in normal animals (“wild type”) or animals treated with 6,000 rads of γ irradiation 4 days (“irradiated”) before surgical removal of heads, trunks, and tails and fixation at time points (h, hours) after amputation. (Upper) wntP-1 expression was detected at posterior-facing wounds in irradiated head fragments at 18 h but not at 96 h. (Lower) wntP-2 expression was detected in the posterior of 96-h heads. Anterior, top. Arrows, new expression of wntP-1 or wntP-2. Panels represent ≥4 of 5 animals. (Scale bars: 200 μm.) (B) Model of regeneration polarity in head fragments. wntP-1 is induced at any wound. Posterior wntP-1 activates wntP-2 through β-catenin-1, possibly acting in parallel with other genes or resulting in activation of other genes that contribute to the polarity decision (gray arrows). The polarity decision is stem-cell-independent, but tail formation subsequently requires neoblast stem cells. Purple spots, wntP-1 expression. Green gradient, wntP-2 expression.

Discussion

A central issue in understanding patterning during regeneration is whether intrinsic properties of morphogen gradients are sufficient to account for pattern restoration or whether tissue patterning requires wound-induced input. Self-regulation during size scaling, regeneration, or regulative development is a widespread but poorly understood phenomenon. During regulative development, missing tissues can be replaced by neighboring tissues. For example, sea urchin blastomeres isolated at the four-cell stage can give rise to an intact sea urchin larva (35), and transplantations of fragments of the vertebrate embryonic limb field can induce the formation of complete limbs rather than partial limbs (2). In another dramatic example, dorsal, but not ventral, halves of amphibian embryos can undergo regulative development to form a normal embryo (36). In Xenopus, this attribute involves rescaling of a signaling network with ventrally expressed BMP2/4/7 and dorsally expressed ADMP ligands (37). Theoretical models of regulative development in Xenopus embryos (10) and other systems (9, 12) suggest that intrinsic properties of the diffusion, degradation, shuttling, and interaction of protein gradients could be sufficient to account for self-regulation to restore missing pattern elements or tissue. However, the molecular mechanisms controlling the property of self-regulation in regeneration are not well understood.

Our data suggest a molecular model of regeneration blastema polarity determination in planarians (Fig. 5B). A wound signal induces wntP-1 expression. wntP-1 acts in the posterior, through β-catenin-1, to induce wntP-2 expression in a stem-cell-independent manner. Because wntP-1 is expressed at anterior- and posterior-facing wounds but promotes wntP-2 expression only at posterior-facing wounds, we suggest that additional factors will be involved in making posterior- rather than anterior-facing wounds a permissive environment for WNTP-1 activity. Because neoblasts are required to make tails but are not required for wntP-1 or wntP-2 expression at wound sites, we propose that neoblasts act after the Wnt-mediated polarity specification process to implement tail formation (Fig. 5B). It is surprising that wntP-1 expression is induced by any wound type because this expression would be unanticipated if resetting of gradients that control body positions was explained solely by properties of the gradients themselves.

Several lines of evidence suggest that it is the wound-induced phase of wntP-1 as opposed to only the later phase of wntP-1 expression that acts in regeneration polarity. First, polarity requires expression of wntP-1 during regeneration. Second, wntP-2 expression in the posterior is activated in a wntP-1-dependent manner at a time (36–42 h) when wntP-1 is expressed dispersely near posterior wounds and before wntP-1 expression coalesces to the posterior pole. wntP-1 expression is also β-catenin-1-independent at this stage. Third, inhibition of wntP-1 caused anteriorization during lateral regeneration, and wntP-1 expression was detected at lateral wounds only at early times during the wound-specific phase of wntP-1 expression. Finally, γ irradiation causes a defect in late but not early wntP-1 expression; under these circumstances, wntP-2 is still activated in the posterior, suggesting that late wntP-1 expression is not responsible for wntP-2 expression. The simplest interpretation of these data is that a β-catenin-1-independent wound signal induces wntP-1 expression near any wound and wntP-1 subsequently controls regeneration polarity. Therefore, these data suggest that pattern formation in planarian regeneration depends on wound-induced cues rather than entirely on intrinsic self-organizing properties of morphogen gradients.

Specific responses to wounding could in principle be an important difference between embryonic regulative development and adult regeneration. Wounding is known to trigger the expression of secreted proteins during appendage regeneration that are important for proliferation, but whether wound-induced cues participate in the control of tissue identity determination during regeneration is not known. For example, fgf20a, wnt10a, and wnt5a expression is induced after amputation of the zebrafish caudal fin (5, 38). Our data suggest that wntP-1, wntP-2, and β-catenin-1 function in polarity independently of the proliferative neoblast stem cells. First, the wound signal that activates early expression of wntP-1 is neoblast-independent. Second, wntP-1 and β-catenin-1 activate wntP-2 near posterior-facing wounds, and wntP-2 activation is also neoblast-independent. It is possible that WNTP-1 and WNTP-2 have multiple roles in regeneration. However, our data indicate that a primary role for newly produced WNTP-1 protein at wounds is in tissue identity determination. How animals can regenerate missing tissue of an appropriate type is a great mystery of biology. Our data from planarians indicate that wound-induced Wnt signaling can act in the specification of the identity of missing parts.

Materials and Methods

Gene Sequences.

Complete sequences for Smed-wntP-1 and Smed-wntP-2 were described previously (EU296630 and EU29663) (22). PDS and sFRP-1 riboprobes (22) and the frizzled-4 riboprobe (23) were described previously. Unless otherwise noted, dsRNA and riboprobes were made from a fragment of wntP-1 (nucleotides 175-1233) and a fragment of wntP-2 (nucleotides 68–1266). For Fig. 4 (42 h), wntP-1 dsRNA was used comprising nucleotides 8–1507 of wntP-1 mRNA.

Fixations, In Situ Hybridizations, and Immunostainings.

Animals were treated in 9% N-acetylcysteine and fixed in Carnoy's solution, as described in ref. 22. Digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes were synthesized as described in ref. 16. In situ hybridizations using were performed as described in ref. 22 using a nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate colorimetric assay. Immunostainings were performed as described in ref. 16. See SI Materials and Methods for details.

RNAi.

RNAi by injection of dsRNA was performed as described in ref. 22. See SI Materials and Methods for details. In situ hybridizations confirmed that wntP-1 and wntP-2 knockdown was efficient (Fig. S6).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank members of the laboratory of P.W.R. for helpful discussions and Jessica Keenan for technical assistance. We acknowledge support by National Institutes of Health R01GM080639 and ACS RSG-07–180-01-DDC, an American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship to C.P.P., and Rita Allen, Searle, Smith, and Keck Foundation support to P.W.R.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0906823106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brockes JP, Kumar A. Comparative aspects of animal regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:525–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison RG. Experiments on the development of the fore-limb of Amblystoma, a self-differentiating equipotential system. J Exp Zool. 1918;25:413–461. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Kicza AM, Sánchez Alvarado A. BMP signaling regulates the dorsal planarian midline and is needed for asymmetric regeneration. Development. 2007;134:4043–4051. doi: 10.1242/dev.007138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molina MD, Saló E, Cebrià F. The BMP pathway is essential for re-specification and maintenance of the dorsoventral axis in regenerating and intact planarians. Dev Biol. 2007;311:79–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitehead GG, Makino S, Lien CL, Keating MT. fgf20 is essential for initiating zebrafish fin regeneration. Science. 2005;310:1957–1960. doi: 10.1126/science.1117637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepilina A, et al. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar A, Godwin JW, Gates PB, Garza-Garcia AA, Brockes JP. Molecular basis for the nerve dependence of limb regeneration in an adult vertebrate. Science. 2007;318:772–777. doi: 10.1126/science.1147710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broun M, Gee L, Reinhardt B, Bode HR. Formation of the head organizer in hydra involves the canonical Wnt pathway. Development. 2005;132:2907–2916. doi: 10.1242/dev.01848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meinhardt H. Models for the generation of the embryonic body axes: Ontogenetic and evolutionary aspects. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Zvi D, Shilo BZ, Fainsod A, Barkai N. Scaling of the BMP activation gradient in Xenopus embryos. Nature. 2008;453:1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/nature07059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolpert L. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J Theor Biol. 1969;25:1–47. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(69)80016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meinhardt H. Models of Biological Pattern Formation. London: Academic; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn CW, et al. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature. 2008;452:745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature06614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyman LH. The Invertebrates: Platyhelminthes and Rhynchocoela the Acoelomate Bilateia. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddien PW, Sánchez Alvarado A. Fundamentals of planarian regeneration. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:725–757. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddien PW, Oviedo NJ, Jennings JR, Jenkin JC, Sánchez Alvarado A. SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells for regeneration and homeostasis. Science. 2005;310:1327–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.1116110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Murfitt KJ, Jennings JR, Sánchez Alvarado A. Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Dev Cell. 2005;8:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newmark PA, Reddien PW, Cebrià F, Sánchez Alvarado A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed double-stranded RNA inhibits gene expression in planarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11861–11865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834205100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sánchez Alvarado A, Newmark PA, Robb SM, Juste R. The Schmidtea mediterranea database as a molecular resource for studying platyhelminthes, stem cells and regeneration. Development. 2002;129:5659–5665. doi: 10.1242/dev.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan TH. Experimental studies of the regeneration of Planaria maculata. Arch Entw Mech Org. 1898;7:364–397. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan TH. “Polarity” considered as a phenomenon of gradation of materials. J Exp Zool. 1905;2:495–506. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Smed-βcatenin-1 is required for anteroposterior blastema polarity in planarian regeneration. Science. 2008;319:327–330. doi: 10.1126/science.1149943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurley KA, Rink JC, Sánchez Alvarado A. β-Catenin defines head versus tail identity during planarian regeneration and homeostasis. Science. 2008;319:323–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1150029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iglesias M, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Saló E, Adell T. Silencing of Smed-βcatenin1 generates radial-like hypercephalized planarians. Development. 2008;135:1215–1221. doi: 10.1242/dev.020289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adell T, Saló E, Boutros M, Bartscherer K. Smed-Evi/Wntless is required for β-catenin-dependent and -independent processes during planarian regeneration. Development. 2009;136:905–910. doi: 10.1242/dev.033761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiecker C, Niehrs C. A morphogen gradient of Wnt/β-catenin signalling regulates anteroposterior neural patterning in Xenopus. Development. 2001;128:4189–4201. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu P, et al. Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:361–365. doi: 10.1038/11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman MA, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-44 controls the polarity of asymmetric cell divisions. Development. 1994;120:1035–1047. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orii H, et al. The planarian HOM/HOX homeobox genes (Plox) expressed along the anteroposterior axis. Dev Biol. 1999;210:456–468. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bardeen CR, Baetjer FH. The inhibitive action of the Roentgen rays on regeneration in planarians. J Exp Zool. 1904;1:191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubois F. Contribution to the study of regenerative cell migration in freshwater planarians (Translated from French) Bull Biol Fr Belg. 1949;83:213–283. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenhoffer GT, Kang H, Sánchez Alvarado A. Molecular analysis of stem cells and their descendants during cell turnover and regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hicklin J, Wolpert L. Positional information and pattern regulation in hydra: The effect of γ-radiation. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1973;30:741–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Driesch H. On the displacement of blastomeres in the echinoderm egg (Translated from German) Anat Anz. 1893;8:348–357. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spemann H. Developmental physiological studies of the Triton egg III (Translated from German) Arch Entw Mech Org. 1903;16:551–631. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Regulation of ADMP and BMP2/4/7 at opposite embryonic poles generates a self-regulating morphogenetic field. Cell. 2005;123:1147–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stoick-Cooper CL, et al. Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development. 2007;134:479–489. doi: 10.1242/dev.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.