Abstract

Group IVA phospholipase A2 (GIVA PLA2) catalyzes the release of arachidonic acid (AA) from the sn-2 position of glycerophospholipids. AA is then further metabolized into terminal signaling molecules including numerous prostaglandins. We have now demonstrated the involvement of phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase 1 (PAP-1) and protein kinase C (PKC) in the Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) activation of GIVA PLA2. We also studied the effect of PAP-1 and PKC on Ca+2 induced and synergy enhanced GIVA PLA2 activation. We observed that the AA release induced by exposure of RAW 264.7 macrophages to the TLR-4 specific agonist Kdo2-Lipid A is blocked by the PAP-1 inhibitors bromoenol lactone (BEL) and propranolol as well as the PKC inhibitor Ro 31-8220; however these inhibitors did not reduce AA release stimulated by Ca+2 influx induced by the P2X7 purinergic receptor agonist ATP. Additionally, stimulation of cells with diacylglycerol (DAG), the product of PAP-1 mediated hydrolysis, initiated AA release from unstimulated cells as well as restored normal AA release from cells treated with PAP-1 inhibitors. Finally, neither PAP-1 nor PKC inhibition reduced GIVA PLA2 synergistic activation by stimulation with Kdo2–Lipid A and ATP.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial sepsis and septic shock result from the exacerbated production of inflammatory mediators by the immune system in response to bacterial endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1). Exposure of macrophages to LPS initiates the Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) signaling pathway, resulting in the release of a host of cytokines and eicosanoids, including various prostaglandins (PGs). PGs are known to contribute to a number of normal and pathological physiological processes, including inflammation, pain, and vascular permeability and are also implicated as major contributors to endotoxic shock (2).

Group IVA phospholipase A2 (GIVA PLA2), also known as the cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), is the proinflammatory phospholipase responsible for the release of arachidonic acid (AA) which is further metabolized into eicosanoids (3,4). GIVA PLA2 catalyzes the hydrolysis of AA from the sn-2 position of membrane phospholipids, resulting in the release of free AA from the membrane and formation of lysophospholipids (5,6). GIVA PLA2 has been implicated in a variety of inflammatory disease models, including collagen induced arthritis, autoimmune encephalomyelitis and acute lung injury; therefore, obtaining a complete understanding of the molecular mechanism of its activation is essential. (7–9).

Phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase 1 (PAP-1) is a Mg+2-dependent, cytosolic enzyme that associates with phosphatidic acid (PA) containing membrane surfaces, where it converts PA into inorganic phosphate and diacylglycerol (DAG) (10–17). With the discovery by Carman and coworkers (17) in 2006 that yeast PAP-1 is the yeast ortholog of Lipin-1 discovered by Reue and coworkers (18); the interest in PAP-1 has escalated. For a recent review of the lipins, see (19). Our laboratory has utilized two different immortalized mammalian cell lines to characterize distinctive signaling pathways in which PAP-1 inhibition leads to the loss of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) expression and PGE2 release. The first study was conducted in the human amnionic WISH cell line utilizing the protein kinase C (PKC) activator phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (18). The second study was conducted in the human U937 macrophage-like cell line stimulated with the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 agonist lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (19). In the macrophage cells, we (21) found in a Western blot that antibody to Lipin-1, and not antibodies to Lipin-2 or Lipin-3, crossreacted with protein at a molecular mass of 140 kDa on SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, the correct molecular mass for Lipin-1 (22), suggesting its presence and that the macrophage PAP-1 is Lipin-1, in analogy to the Carman finding in yeast (16,17). Drawing on these studies and other published reports, we hypothesized that DAG evolved from PAP-1 is likely to activate PKC, which has been shown to cause the phosphorylation of GIVA PLA2 in cellular studies conducted with phorbol esters (20–23).

In this manuscript, we provide further evidence that inhibition of PAP-1 or PKC results in reduced GIVA PLA2 activation in macrophages stimulated with the TLR-4 specific agonist, Kdo2-Lipid A (24). Furthermore, we observed that exposure of cells to the inhibitors did not reduce GIVA PLA2 -mediated AA release initiated with Ca+2 influx via ATP. Finally, our data suggests that inhibition of PAP-1 or PKC does not affect synergistic activation of GIVA PLA2, despite reducing the absolute amount of AA released from cells that have been stimulated with both Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP stimuli.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Murine RAW 264.7 macrophages were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). DMEM cell culture medium was obtained from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Fetal bovine serum was from VWR International (Bristol, CT). DTT and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), from E. coli 0111:B4, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Kdo2-Lipid A, 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl phosphatidylcholine was from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Propranolol, Dioctoyl-DAG and Ro 31-8220 were from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Bromoenol lactone (BEL) was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). 1-palmitoyl-2-(1-14C)-palmitoyl phosphatidylcholine, 1-palmitoyl-2-(1-14C)-arachidonoyl phosphatidylcholine, [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H] arachidonic acid (specific activity = 100 Ci/mmol) and [9,10-3H] oleic acid (specific activity = 23 Ci/mmol) were obtained from NEN Life Science Products (Boston, MA). Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate was from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). The specific cPLA2 inhibitor, pyrrophenone, was kindly provided by Dr. Kohji Hanasaki (Shionogi Research Laboratories of Shionogi & Co., Ltd). 20 cm × 20 cm × 250 μm K6 Silica gel thin layer chromatography plates were from Whatman (Clifton, New Jersey).

Cell Culture and Stimulation Protocol

RAW 264.7 macrophages were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere at 90% air and 5% CO2 DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and non-essential amino acids. Cells were plated at a confluency of 2×106 cells/6 well tissue culture plate and 1×106/12 well tissue culture plate at the time of experimentation. Following plating, they were allowed to adhere overnight, and then used for experiments the following day, with the exception of cells that were radiolabeled, described below. When DAG was added to the cells, it was done immediately after the addition of Kdo2-Lipid A. Whenever cellular experiments required the usage of chemical inhibitors; the inhibitors were initially diluted into media at a stock concentration that was 100 times more concentrated than that of the final cellular concentration. From this stock concentration, the inhibitors were then applied to the cells to achieve the desired final cellular concentration. The final concentration of DMSO in the supernatants never exceeded .05% (volume/volume). When synergy experiments were performed, ATP was added to cells treated with Kdo2-Lipid A 50 minutes after Kdo2-Lipid A stimulation, and supernatants were collected at 1 hour following stimulation. Cell viability was assessed visually by the Trypan Blue Dye exclusion assay (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and through the usage of the CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

Sample Preparation

Media was analyzed for extracellular eicosanoid release, as described previously (25). After stimulation, 1.8 ml of media was removed and supplemented with 100 μl of internal standards (100 pg/μl, EtOH) and 100 μl EtOH to bring the total EtOH to 10% by volume. Samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3000 rpm to remove cellular debris, and the supernatants were decanted into solid phase extraction columns. All eicosanoid extractions were conducted using Strata-X SPE columns (Phenomenex). The columns were washed with 2 ml MeOH and then 2 ml H2O prior to the samples being applied. After applying the sample, the columns were washed with 10% MeOH to remove non-adherent debris, and eicosanoids were then eluted off the column with 1 ml MeOH. The eluant was dried under vacuum and redissolved in 100 μl of solvent A [water-acetonitrile-formic acid (63:37:0.02; v/v/v)] for LC/MS analysis.

Cell Quantitation

Eicosanoid levels were normalized to cell number using DNA quantitation. After the extracellular media was removed, the cells were scraped in 500 μl PBS and stored at 4°C for DNA quantitation using the Broad Range DNA Quant-Kit (Invitrogen).

HPLC and Mass Spectrometry

The analysis of eicosanoids was performed by LC/MS/MS (26). Eicosanoids were separated by reverse-phase HPLC on a C18 column (2.1 mm × 150 mm, Grace-Vydac) at a flow rate of 300 μl/min at 25°C. The column was equilibrated in Solvent A [water-acetonitrile-formic acid (63:37:0.02; v/v/v)], and samples were injected using a 50 μl injection loop and eluted with a linear gradient from 0%–20% solvent B [acetonitrile-isopropyl alcohol (50:50; v/v)] between 0 to 6 min; solvent B was increased to 55% from 6 to 6.5 min and held until 10 min. Solvent B was increased to 100% from 10 to 12 min and held until 13 min; solvent B was dropped to 0% by 13.5 min and held until 16 min.

Eicosanoids were analyzed using a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer (ABI 4000 Q Trap®, Applied Biosystems) via multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) in negative-ion mode. The electrospray voltage was −4.5 kV, the turbo ion spray source temperature was 525°C. Collisional activation of eicosanoid precursor ions used nitrogen as a collision gas. While arachidonic acid and its major metabolites (referred to as eicosanoids) were detected, by far the major species at one hour was arachidonic acid, which was the focus of this study; for quantitation of the major eicosanoids produced, see (30).

Quantitative eicosanoid determination was performed by stable isotope dilution, as previously described (26). Results are determined as pmol of AA per million cells (mean ± standard deviation).

RESULTS

PAP-1 inhibition reduces Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release

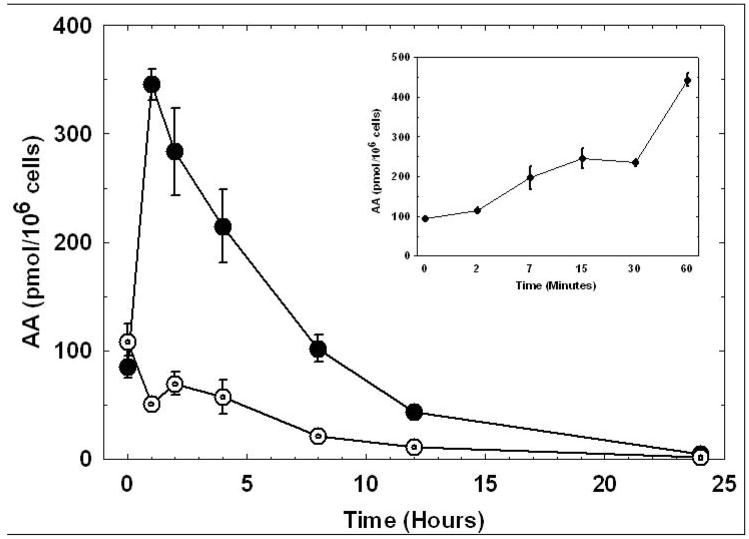

We initiated this study by characterizing GIVA PLA2-mediated AA release from RAW 264.7 macrophages that were stimulated with Kdo2-Lipid A. Kdo2-Lipid A is a truncated LPS structure which is a specific binding-agonist of TLR-4 (24). The AA release time-course experiments were conducted over a period of 24 hours. As described in Figure 1, the maximal release of AA was observed to be 300–400 pmol AA/106 cells at 1 hour after stimulation, after which AA release gradually returned to baseline levels. Subsequent AA release experiments were conducted at one hour following stimulation as this was determined to be the most optimal time point.

Figure 1. Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release time-course.

RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured in the presence (•) or absence (○) of 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A, the media was collected at the indicated time points and then subsequently analyzed for AA release by HPLC-MS. The insert is a separate experiment showing Kdo2–Lipid A stimulated AA release over a 60 minute time-course. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

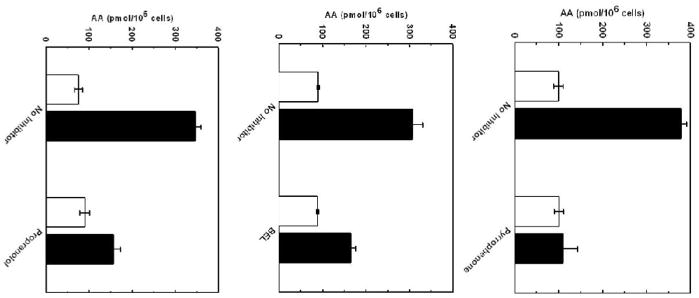

To ensure that GIVA PLA2 is the enzyme that is responsible for mediating AA release under the experimental conditions employed, cells were pretreated with the GIVA PLA2 specific inhibitor pyrrophenone (31) prior to stimulation. Pretreatment of the cells with pyrrophenone reduced Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release to background levels, as shown in Figure 2A; this result indicates that the Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release is mediated through the activity of GIVA PLA2.

Figure 2. Inhibition of PAP-1 blocks the Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated release of AA.

AA release was measured from RAW 264.7 macrophages preincubated with and without (A) 1 μM pyrrophenone, (B) 25 μM BEL, or (C) 50 μM propranolol prior to stimulation with (■) and without (□) 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A. The media was collected at 1 hour following Kdo2-Lipid A stimulation and analyzed for AA release by HPLC-MS. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

To evaluate whether PAP-1 may participate in the activation of GIVA PLA2, we preincubated cells with the PAP-1 inhibitors BEL and propranolol prior to stimulation of the cells. Preincubation of the cells with bromoenol lactone (BEL) resulted in a ~70% decrease of Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release into the supernatant, as seen in Figure 2B. This result was corroborated by repeating the experiment with another inhibitor of PAP-1, propranolol, as shown in Figure 2C.

To address the possibility that PLC may play a role in this pathway, cells were treated with the classic PLC inhibitors D609 and U-71322 prior to stimulation with Kdo2-Lipid A; neither inhibitor reduced AA release, suggesting that PLC is not involved in this signaling cascade (data not shown).

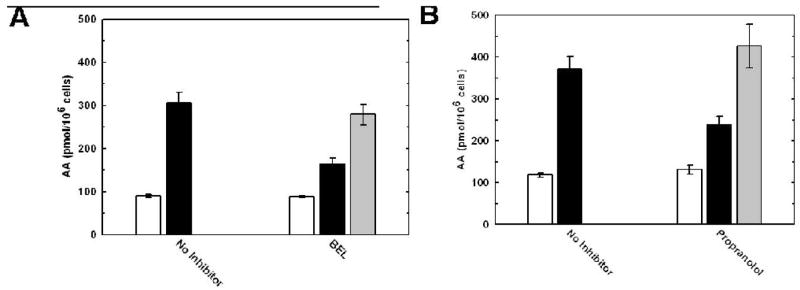

BEL and propranolol do not inhibit ATP stimulated AA release

The inhibitor data summarized in Figures 2B and 2C suggest that PAP-1 participates in the TLR-4 mediated activation of GIVA PLA2. Cellular GIVA PLA2 activity can also be induced by the treatment of cells with Ca+2 mobilizing agonists, such as the purinergic P2X7 receptor agonist ATP. Inhibited and uninhibited cells were treated with ATP prior to AA release quantitation. Stimulation of macrophages with ATP increased AA release into the supernatant (Figure 3). To ensure that the Ca+2 agonists had induced AA release via participation of GIVA PLA2, cells were also treated with pyrrophenone prior to stimulation; exposure to pyrrophenone resulted in reduction of AA release to background levels. Neither BEL nor propranolol reduced AA release induced by this stimulus, indicating that the inhibitors do not affect GIVA PLA2.

Figure 3. Inhibition of PAP-1 does not block the ATP stimulated release of AA.

AA release was measured from RAW 264.7 macrophages preincubated with and without 1 μM pyrrophenone, 25 μM BEL or 50 μM propranolol prior to stimulation with (■) and without (□) 2 mM ATP. The media was collected at 10 minutes following stimulation and analyzed for AA release. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

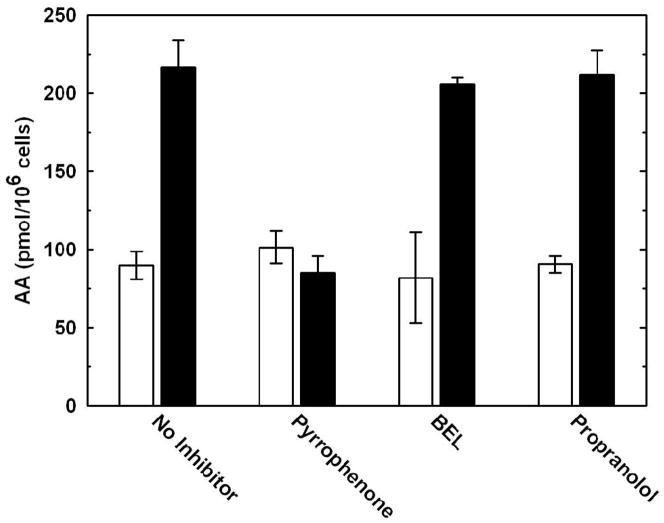

As an additional control, to ensure that an extracellular Ca+2 influx into the cell is not required in the TLR-4 mediated activation of the GIVA PLA2, cells were cultured in the presence of EDTA and EGTA prior to stimulation with Kdo2-Lipid A. Neither EDTA nor EGTA reduced the AA release, indicating that Ca+2 influx is not required for TLR-4 mediated activation of the GIVA PLA2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Ca+2 chelators EDTA and EGTA do not reduce Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release.

A, AA release was measured from RAW 264.7 macrophages preincubated with and without 2 mM EDTA or EGTA prior to stimulation with (■) and without (□) 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A. The media was collected at 1 hour following stimulation and analyzed for AA release. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

PAP-1 chemical inhibition does not reduce the synergistic activation of GIVA PLA2

Recently, we reported that cells that were stimulated with both Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP released more AA than the sum of AA released from cells stimulated separately, a phenomena referred to as synergy (27). The extent to which AA release is enhanced by joint Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP stimuli can be calculated from:

| Equation 1 |

When synergy is present, the synergistic activation value is greater than 1.0, as joint Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP stimulation result in AA release that exceeds the sum of the individual stimulations. If no synergy is present, and therefore joint stimulation equals the sum total of separate stimulations, the value will equal 1.0. Synergy-enhanced GIVA PLA2 activation results in enhanced AA release that exceeds the sum total of TLR-4 and Ca+2 mediated AA releases.

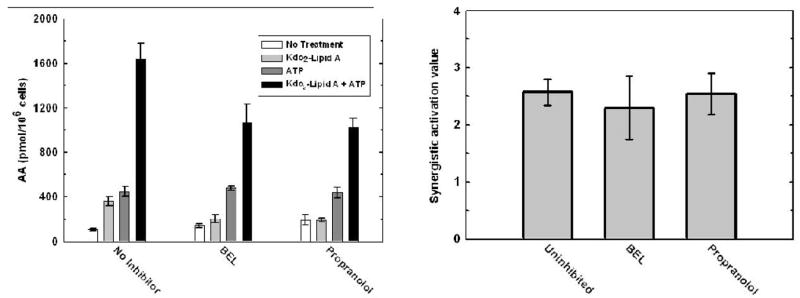

In the current study, sequential treatment of cells with Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP resulted in a synergistic activation value of 2.5±0.4, as shown in Figure 5A. In this particular example, cells that were treated with Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP released 1,600 pmol AA/106 cells, which is four times greater than the amount of AA released by either Kdo2-Lipid A or ATP alone and approximately 2.5 times greater than the sum total of separate Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP stimulations. It is important to note that the absolute level of AA released via the [Kdo2-Lipid A + ATP] stimulation shown in Figure 5A is not an indicator of synergy. To determine the extent to which synergy activation is present, one must compute the synergistic activation value through equation 1 and then evaluate it relative to a value of “1”.

Figure 5. Inhibition of PAP-1 blocks synergy-enhanced AA release, but does not reduce the synergistic activation value.

A, AA release was measured from RAW 264.7 macrophages preincubated with and without 25 μM BEL or 50 μM propranolol prior to stimulation with and without 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A for 50 minutes and with and without 2 mM ATP for 10 minutes (as indicated in the legend). The media was collected at 1 hour following the addition of the 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A agonist and analyzed for AA release. B, Synergistic activation values were calculated for uninhibited cells, preincubated with 25 μM BEL or 50 μM propranolol. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

Figures 2 and 3 show that preincubation of macrophages with either BEL or propranolol prior to Kdo2-Lipid A treatment reduces AA release, whereas neither inhibitor affects ATP stimulated AA release. Similarly, preincubation of the cells with BEL or propranolol reduces the AA released from cells treated with [Kdo2-Lipid A + ATP], as shown in Figure 5A. However, despite the reduction in [Kdo2-Lipid A + ATP] stimulated AA release, the synergistic activation value was not reduced by the presence of the inhibitors (Figure 5B). This suggests that PAP-1 inhibition reduces AA release from cells treated with [Kdo2-Lipid A + ATP] by reducing the Kdo2-Lipid A portion of the stimulation, while not affecting the contribution of the synergy stimulus.

Exogenous DAG stimulates GIVA PLA2-mediated AA release

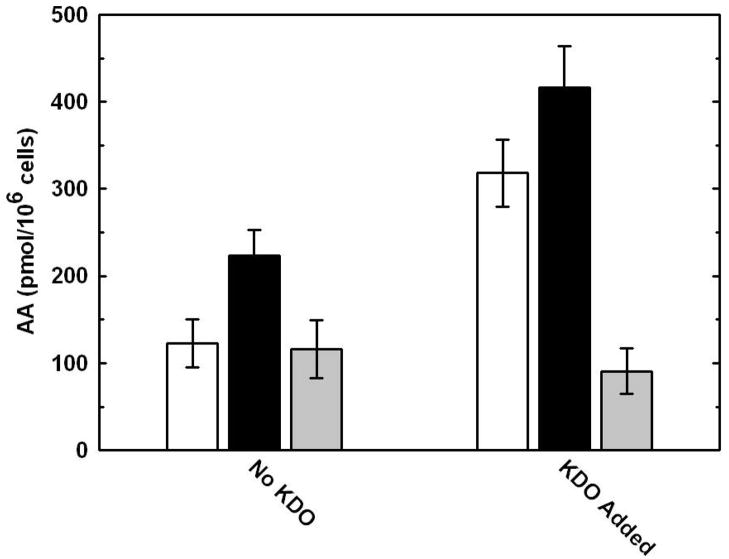

Since PAP-1 converts cellular PA into DAG, macrophages were treated with exogenous DAG to assess whether this would elicit AA release. The addition of DAG to unstimulated cells slightly increased AA release into the supernatant. Additionally, the supplementation of DAG to Kdo2-Lipid A treated cells resulted in a further increased AA release from the cells relative to that of cells that were treated with only Kdo2-Lipid A (Figure 6). To ensure that the enhanced AA release was due to additional activation of GIVA PLA2, we preincubated cells with pyrrophenone prior to stimulation. Pyrrophenone inhibited AA release to background levels in both cases, indicating that the enhanced AA release elicited by DAG is mediated through the action of GIVA PLA2.

Figure 6. Exogenous DAG bolsters the Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated release of AA.

AA release into the media was measured from RAW 264.7 macrophages that were stimulated with and without 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A (as indicated) and in the absence (white bars) and presence (black bars) of 50 μM DAG for 1 hour. Additionally, grey bars indicate AA release from cells preincubated with 1 μM pyrrophenone for 30 minutes prior to the addition of DAG. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

Exogenous DAG restores AA release from macrophages inhibited by propranolol or BEL

We investigated whether the addition of exogenous DAG in an “add-back” fashion would restore AA release from cells that had been pretreated with BEL or propranolol. The addition of DAG to cells that had been pretreated with the PAP-1 inhibitors prior to stimulation with Kdo2-Lipid A resulted in full restoration of AA release to levels seen in uninhibited cells (Figure 7A and B). This result suggests that the effect of PAP-1 inhibition is reversible by the addition of DAG, which is the product of PAP-1 mediated hydrolysis.

Figure 7. DAG supplementation restores AA release from Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages pretreated with PAP-1 inhibitors.

AA release was measured from cells preincubated with and without (A) 25 μM BEL or (B) 50 μM propranolol (as indicated) prior to stimulation with 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A (black bars) and 50 μM DAG (grey bars). The media was collected at 1 hour following stimulation and analyzed for AA release. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

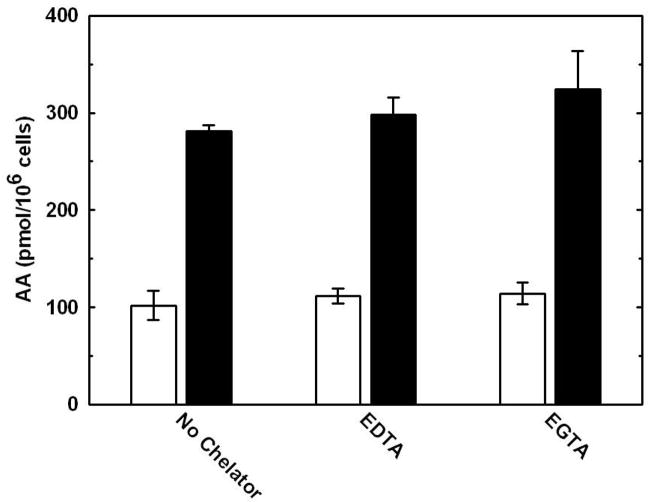

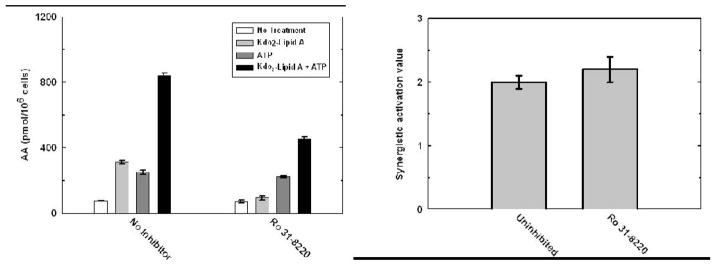

PKC chemical inhibition inhibits Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release, but not synergistic activation

Since our data suggests that inhibition of PAP-1 results in decreased Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release but does not affect the synergistic activation of GIVA PLA2, we next investigated whether inhibition of PKC would corroborate the PAP-1 inhibitory data. Cells were treated with the general PKC inhibitor Ro 31-8220 prior to stimulation with Kdo2-Lipid A, ATP and [Kdo2-Lipid A + ATP] and the synergistic activation value was computed. Similar to that of the PAP-1 inhibitor results, inhibition of PKC resulted in baseline reduction of Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release and also significantly reduced [Kdo2-Lipid A + ATP] stimulated AA release, while not having a significant affect on ATP stimulation (Figure 8A). Also, consistent with the PAP-1 inhibitory data, the synergistic activation value was not reduced relative to that of the uninhibited cells (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Inhibition of PKC blocks synergy-enhanced AA release, but does not reduce the synergistic activation value.

A, AA release was measured from RAW 264.7 macrophages preincubated with and without 5 μM Ro 31-8220 prior to stimulation with and without 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A for 50 minutes and with and without 2 mM ATP for 10 minutes (as indicated in the legend). The media was collected at 1 hour following the addition of the 100 ng/mL Kdo2-Lipid A agonist and analyzed for AA release. B, Synergistic activation values were calculated for uninhibited cells and those preincubated with 5 μM Ro 31-8220. A representative experiment of three individual experiments is shown. Data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

DISCUSSION

The focus of this research was to investigate the relationship between PAP-1, PKC and the activation of GIVA PLA2 in the TLR-4 signaling cascade. To evaluate cellular GIVA PLA2 activity, macrophages were stimulated with the TLR-4 specific agonist Kdo2-Lipid A and then AA release into the supernatant was quantitated as a metabolic indicator of GIVA PLA2 function. In previous studies in which AA release was quantitated from macrophages, our laboratory and others made use of scintillation counting of radioactive AA as well as EIA quantitation of PGE2 secreted to the supernatant as an indicator of cellular GIVA PLA2 activity (19,28–31). Both techniques have important limitations that must be accounted for. Scintillation counting does not discriminate between AA release and AA-derived metabolites, such as eicosanoids. Utilization of commercial EIA kits to measure PGE2 release as an indicator of AA release makes the assumption that PGE2 release is a direct indicator of cellular AA release. In the current study, we make use of HPLC-MS methodology to quantitate AA release specifically from unlabelled cells.

We began this study by conducting time courses of AA release from macrophages stimulated with Kdo2-Lipid A to evaluate the optimal time to measure AA release following cellular activation. Maximal AA release into the supernatant was observed at one hour following stimulation, and therefore this was chosen to be the time point at which subsequent experiments were conducted. Since AA release was utilized as an indicator of cellular GIVA PLA2 activity, it was imperative to ensure that Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release was mediated via GIVA PLA2. To achieve this, macrophages were pretreated with the GIVA PLA2 specific inhibitor, pyrrophenone, prior to stimulation with Kdo2-Lipid A. Pyrrophenone reduced AA release to background levels, indicating that GIVA PLA2 is responsible for Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release.

To investigate whether PAP-1 participates in the Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated GIVA PLA2 activation, cells were treated with the PAP-1 inhibitors BEL and propranolol prior to stimulation. Preincubation of cells with BEL or propranolol resulted in a marked reduction of AA release into the supernatant. Since this result could be explained by direct inhibition of GIVA PLA2, we studied the effect of the inhibitors on AA release from cells stimulated with the Ca+2 mobilizing agent, ATP. ATP activates GIVA PLA2 by raising the cellular Ca+2 levels, rather than through a TLR-4-mediated mechanism (30). Neither BEL nor propranolol reduced AA release from cells stimulated with ATP, indicating that the reduced Kdo2-Lipid A stimulated AA release is not due to direct inhibition of cellular GIVA PLA2 activity. It is worth noting that we have shown in a previous publication that activation of TLR-4 in macrophages does not increase intracellular Ca+2 levels (32). Additionally, we confirmed in this manuscript that AA release from cells stimulated with ATP is mediated through GIVA PLA2 by pyrrophenone inhibition. For the sake of completion, we investigated whether DAG generated by PLC may play a role in GIVA PLA2 activation by dosing cells with the PLC inhibitors D609 and U-71322 prior to stimulation; neither inhibitor had an affect, suggesting that PLC is not involved.

Since our data suggests that PAP-1 inhibition reduced GIVA PLA2 activation in Kdo2-Lipid A treated cells, it was logical to assess what the effect of introducing DAG would be on GIVA PLA2 activation. To evaluate whether DAG would directly activate cellular GIVA PLA2, cells were stimulated with exogenous DAG prior to the measurement of AA release into the supernatant. The addition of DAG alone significantly increased AA release, relative to that of control cells. Additionally, supplementation of DAG to macrophages that were also pretreated with Kdo2-Lipid A resulted in enhanced AA release into the supernatant. The AA release was confirmed to be mediated through GIVA PLA2 by pyrrophenone inhibition. Taken in conjunction with the PAP-1 inhibitory data, the fact that DAG evoked AA release suggests that DAG formation is an essential step in the stimulation of GIVA PLA2 catalysis (33–37). Furthermore, considering the fact that the PAP-1 and PKC inhibitory data are similar would suggest that PKC is a likely molecular target of PAP-1 that also participates in the activation mechanism (38). Additionally, since PAP-1 inhibition reduced AA release, exogenous DAG was added to PAP-1 inhibited cells to discern whether this would restore AA release. It did restore AA release to levels released from uninhibited cells, suggesting that introduction of the DAG had compensated for the blocked PAP-1.

In a recent publication, our laboratory described the synergistic activation of GIVA PLA2 in macrophages that had been treated with Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP, resulting in AA release that exceeded the sum total of separate Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP stimulations. This phenomenon has been referred to as synergy (27), whereby in combination Kdo2-Lipid A activates GIVA PLA2 by eliciting TLR-4 signaling and ATP does it through increased cellular Ca+2; but somehow leading to more product than the sum of each acting alone. Our current data suggest that these two activation mechanisms are quite distinct. First, it is shown that PAP-1 and PKC inhibition do not affect ATP stimulation, whereas they have a pronounced affect on Kdo2-Lipid A mediated activation. Second, by adding EGTA and EDTA to chelate extracellular Ca+2, we have shown that Kdo2-Lipid A does not require an influx of Ca+2, unlike ATP.

In the current manuscript, we have expanded upon our previous knowledge of GIVA PLA2 synergistic activation by studying the chemical inhibition of the TLR-4 signaling while observing the effect upon synergy. Initially, PAP-1 chemical inhibitors were employed with the observation that PAP-1 inhibition resulted in a reduction of [Kdo2-Lipid A and ATP] stimulated AA release, while the synergistic activation was unaffected. A likely explanation for this observation is that PAP-1 participates in the TLR-4 mediated signaling mechanism leading to GIVA PLA2 activation, but does not participate in the synergistic activation. Possibilities for other independent effects of the TLR-4 activation are discussed elsewhere (30). Furthermore, this data suggests that blockage of the TLR-4 signaling mechanism does not inhibit activation of GIVA PLA2 through synergy. To confirm this data, the general PKC inhibitor Ro 31-8220 was employed to block PKC, which lies downstream of PAP-1 in this pathway. Interestingly, inhibition of PKC resulted in total blockage of AA release elicited from cells stimulated with Kdo2-Lipid A while not reducing the synergistic activation value. This demonstrates that full inhibition of the TLR-4 signaling cascade leading to GIVA PLA2 does not result in a reduction in synergistic activation, further suggesting that GIVA PLA2 synergistic activation is the result of a unique signaling mechanism.

It is now known that the mammalian lipins 1, 2 and 3 exhibit PAP activity similar to the PAH1 gene product of yeast (43). Using qRT-PCR we have found in RAW cells that lipin 1 is expressed at significant levels. We also found that lipin 2 is expressed at even higher levels, but did not detect lipin 3 to any significant extent (data not shown). Therefore, we did not differentiate the extent to which each of the lipins contributes to the observed PAP-associated effects.

In summary, we present data that suggests that the activation of GIVA PLA2 by Kdo2-Lipid A requires the participation of PAP-1; it is likely that the function of PAP-1 in this model is to activate PKC. Four lines of evidence support such a theory. First, it is known that GIVA PLA2 undergoes phosphorylation and activation involving PKC through a number of agonist-induced signaling pathways, including TLR-4 via LPS (42,44–46). Gene deletion or chemical inhibition of PKC in these studies resulted in loss of agonist-induced GIVA PLA2 phosphorylation with reduced arachidonic acid release. Direct activation of PKC by the agonist PMA has been shown to result in the release of arachidonic acid and GIVA PLA2 activation in a number of macrophage cell lines, including RAW 264.7 and U937 (20,42,43).

Second, all three proteins have been observed to co-localize on the nuclear membrane surface. PAP-1 contains a nuclear localization sequence and the protein expression is concentrated to the nuclear membrane region of HEK293 and 3T3-L1 cells (49,50). PKC has been shown to translocate to the nuclear membrane with rising membrane levels of DAG (51,52). Likewise, GIVA PLA2 associates with the nuclear membrane after phosphorylation (53).

Third, PAP-1 was found to be associated with PKCε and epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor in EGF receptor immunoprecipitates. Following treatment with EGF and a second immunoprecipitation with an anti-PKCε antibody, PAP-1 was found to be associated with PKCε (54). GIVA PLA2 is known to undergo phosphorylation and activation with subsequent AA release by way of an oxidative stress EGF receptor mediated pathway (55).

Finally, we have previously described that PAP-1 participates in TLR-4 mediated COX-2 expression, and our current results suggest that PAP-1 also participates in the TLR-4 activation of the GIVA PLA2 (18,19). Collectively, these results suggest that PAP-1 plays a significant role in inflammatory signaling within the TLR-4 activated macrophage. Of course, these conclusions about the role of PAP-1 are based heavily on the inhibitor studies reported herein and, of course, “a specific inhibitor is one that has not yet been shown to lack specificity”. While BEL and propranolol undoubtedly have other activities in cells, the overall argument for a PAP-1 role depends on their being specific for the specified steps in the TLR-4 activation of GIVA PLA2. The observation that these inhibitors do not affect the activation with ATP bolsters the argument, but does not prove specificity, so additional approaches to test this hypothesis are certainly warranted.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant GM64611 and utilized HPLC-MS equipment supported by LIPID MAPS NIH grant GM069335

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Van Amersfoort ES, Van Berkel TJ, Kuiper J. Receptors, mediators, and mechanisms involved in bacterial sepsis and septic shock. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:379–414. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.3.379-414.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bos CL, Richel DJ, Ritsema T, Peppelenbosch MP, Versteeg HH. Prostanoids and prostanoid receptors in signal transduction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1187–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang YJ, Lu B, Choy PC, Hatch GM. Regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 expression by PMA, TNFalpha, LPS and M-CSF in human monocytes and macrophages. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;246:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieter P, Kolada A, Kamionka S, Schadow A, Kaszkin M. Lipopolysaccharide-induced release of arachidonic acid and prostaglandins in liver macrophages: regulation by Group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2, but not by Group V and Group IIA secretory phospholipase A2. Cell Signal. 2002 Mar;14(3):199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alonso F, Henson PM, Leslie CC. A cytosolic phospholipase in human neutrophils that hydrolyzes arachidonoyl-containing phosphatidylcholine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;878:273–280. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer RM, Checani GC, Deykin A, Pritzker CR, Deykin D. Solubilization and properties of Ca2+-dependent human platelet phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;878:394–403. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagase T, Uozumi N, Ishii S, Kume K, Izumi T, Ouchi Y, Shimizu T. Acute lung injury by sepsis and acid aspiration: a key role for cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nat Immunol. 2000 Jul;1(1):42–6. doi: 10.1038/76897. 1:42–46 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marusic S, Leach MW, Pelker JW, Azoitei ML, Uozumi N, Cui J, Shen MW, DeClercq CM, Miyashiro JS, Carito BA, Thakker P, Simmons DL, Leonard JP, Shimizu T, Clark JD. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha-deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:841–851. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegen M, Sun L, Uozumi N, Kume K, Goad ME, Nickerson-Nutter CL, Shimizu T, Clark JD. Cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha-deficient mice are resistant to collagen-induced arthritis. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1297–1302. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell MP, Brindley DN, Hubscher G. Properties of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase. Eur J Biochem. 1971;18:214–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith ME, Sedgwick B, Brindley DN, Hubscer G. The role of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase in glyceride biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1967;3:70–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1967.tb19499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walton PA, Possmayer F. Translocation of Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphohydrolase between cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum in a permanent cell line from human lung. Biochem Cell Biol. 1986;64:1135–1140. doi: 10.1139/o86-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walton PA, Possmayer F. The role of Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphohydrolase in pulmonary glycerolipid biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;796:364–372. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(84)90139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturton RG, Brindley DN. Factors controlling the metabolism of phosphatidate by phosphohydrolase and phospholipase A-type activities. Effects of magnesium, calcium and amphiphilic cationic drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;619:494–505. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(80)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton PA, Possmayer F. Mg2-dependent phosphatidate phosphohydrolase of rat lung: development of an assay employing a defined chemical substrate which reflects the phosphohydrolase activity measured using membrane-bound substrate. Anal Biochem. 1985;151:479–486. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carman GM, Han GS. Roles of phosphatidate phosphatase enzymes in lipid metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han GS, Wu WI, Carman GM. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lipin homolog is a Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9210–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600425200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Péterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat Genet. 2001;27:121–124. doi: 10.1038/83685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reue K, Dwyer JR. Lipin proteins and metabolic homeostasis. J Lipid Res. 2008 doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800052-JLR200. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson CA, Balboa MA, Balsinde J, Dennis EA. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by phosphatidate phosphohydrolase in human amnionic WISH cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27689–27693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grkovich A, Johnson CA, Buczynski MW, Dennis EA. Lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human U937 macrophages is phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase-1-dependent. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32978–32987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huffman TA, Mothe-Satney I, Lawrence JC., Jr Insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of lipin mediated by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1047–1052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022634399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Y, Lu Z, Zang Q, Foster DA. Regulation of phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase by epidermal growth factor. Reduced association with the EGF receptor followed by increased association with protein kinase Cepsilon. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29529–29532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Exton JH. Signaling through phosphatidylcholine breakdown. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Exton JH. Phosphatidylcholine breakdown and signal transduction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1212:26–42. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Testerink C, Munnik T. Phosphatidic acid: a multifunctional stress signaling lipid in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raetz CR, Garrett TA, Reynolds CM, Shaw WA, Moore JD, Smith DC, Jr, Ribeiro AA, Murphy RC, Ulevitch RJ, Fearns C, Reichart D, Glass CK, Benner C, Subramaniam S, Harkewicz R, Bowers-Gentry RC, Buczynski MW, Cooper JA, Deems RA, Dennis EA. Kdo2-Lipid A of Escherichia coli, a defined endotoxin that activates macrophages via TLR-4. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1097–1111. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600027-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deems R, Buczynski MW, Bowers-Gentry R, Harkewicz R, Dennis EA. Detection and quantitation of eicosanoids via high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2007;432:59–82. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)32003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall LM, Murphy RC. Activation of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes by products derived from the peroxidation of human red blood cell membranes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:1024–1031. doi: 10.1021/tx9801155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buczynski MW, Stephens DL, Bowers-Gentry RC, Grkovich A, Deems RA, Dennis EA. TLR-4 and sustained calcium agonists synergistically produce eicosanoids independent of protein synthesis in RAW264.7 cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22834–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke JE, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 Biochemistry. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10557-008-6132-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balboa MA, Balsinde J, Dennis EA. Involvement of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase in arachidonic acid mobilization in human amnionic WISH cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7684–7690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balboa MA, Perez R, Balsinde J. Amplification mechanisms of inflammation: paracrine stimulation of arachidonic acid mobilization by secreted phospholipase A2 is regulated by cytosolic phospholipase A2-derived hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid. J Immunol. 2003;171:989–994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Dennis EA. Inflammatory activation of arachidonic acid signaling in murine P388D1 macrophages via sphingomyelin synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20373–20377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balsinde J. Roles of various phospholipases A2 in providing lysophospholipid acceptors for fatty acid phospholipid incorporation and remodeling. Biochem J. 2002;364:695–702. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asmis R, Randriamampita C, Tsien RY, Dennis EA. Intracellular Ca2+, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and additional signalling in the stimulation by platelet-activating factor of prostaglandin E2 formation in P388D1 macrophage-like cells. Biochem J. 1994;298(Pt 3):543–551. doi: 10.1042/bj2980543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Li WH, Llopis J, Dennis EA. Cellular regulation of cytosolic group IV phospholipase A2 by phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate levels. J Immunol. 2000;164:5398–5402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosior M, Six DA, Dennis EA. Group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2 binds with high affinity and specificity to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate resulting in dramatic increases in activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2184–2191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casas J, Gijon MA, Vigo AG, Crespo MS, Balsinde J, Balboa MA. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate anchors cytosolic group IVA phospholipase A2 to perinuclear membranes and decreases its calcium requirement for translocation in live cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:155–162. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pettus BJ, Bielawska A, Subramanian P, Wijesinghe DS, Maceyka M, Leslie CC, Evans JH, Freiberg J, Roddy P, Hannun YA, Chalfant CE. Ceramide 1-phosphate is a direct activator of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11320–11326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pettus BJ, Bielawska A, Spiegel S, Roddy P, Hannun YA, Chalfant CE. Ceramide kinase mediates cytokine- and calcium ionophore-induced arachidonic acid release. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38206–38213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo SF, Lin WN, Yang CM, Lee CW, Liao CH, Leu YL, Hsiao LD. Induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by lipopolysaccharide in canine tracheal smooth muscle cells: involvement of MAPKs and NF-kappaB pathways. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1201–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carman GM, Han GS. Phosphatidic acid phosphatase, a key enzyme in the regulation of lipid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;284:2593–2597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800059200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu J, Weng YI, Simonyi A, Krugh BW, Liao Z, Weisman GA, Sun GY. Role of PKC and MAPK in cytosolic PLA2 phosphorylation and arachadonic acid release in primary murine astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2002;83:259–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J, Weng YI, Simonyi A, Krugh BW, Liao Z, Weisman GA, Sun GY. Role of PKC and MAPK in cytosolic PLA2 phosphorylation and arachadonic acid release in primary murine astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2002;83:259–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Q, Subbulakshmi V, Oldfield CM, Aamir R, Weyman CM, Wolfman A, Cathcart MK. PKCalpha regulates phosphorylation and enzymatic activity of cPLA2 in vitro and in activated human monocytes. Cell Signal. 2007;19:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin WW, Chen BC. Distinct PKC isoforms mediate the activation of cPLA2 and adenylyl cyclase by phorbol ester in RAW264.7 macrophages. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1601–1609. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Insel PA, Dennis EA. Differential regulation of phospholipase D and phospholipase A2 by protein kinase C in P388D1 macrophages. Biochem J. 1997;321(Pt 3):805–809. doi: 10.1042/bj3210805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peterfy M, Phan J, Reue K. Alternatively spliced lipin isoforms exhibit distinct expression pattern, subcellular localization, and role in Adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32883–32889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat Genet. 2001;27:121–124. doi: 10.1038/83685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deacon EM, Pettitt TR, Webb P, Cross T, Chahal H, Wakelam MJ, Lord JM. Generation of diacylglycerol molecular species through the cell cycle: a role for 1-stearoyl, 2-arachidonyl glycerol in the activation of nuclear protein kinase C-betaII at G2/M. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:983–989. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Divecha N, Banfic H, Irvine RF. The polyphosphoinositide cycle exists in the nuclei of Swiss 3T3 cells under the control of a receptor (for IGF-I) in the plasma membrane, and stimulation of the cycle increases nuclear diacylglycerol and apparently induces translocation of protein kinase C to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1991;10:3207–3214. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marshall J, Krump E, Lindsay T, Downey G, Ford DA, Zhu P, Walker P, Rubin B. Involvement of cytosolic phospholipase A2 and secretory phospholipase A2 in arachidonic acid release from human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2000;164:2084–2091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang Y, Lu Z, Zang Q, Foster DA. Regulation of phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase by epidermal growth factor. Reduced association with the EGF receptor followed by increased association with protein kinase Cepsilon. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29529–29532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pawliczak R, Huang XL, Nanavaty UB, Lawrence M, Madara P, Shelhamer JH. Oxidative stress induces arachidonate release from human lung cells through the epithelial growth factor receptor pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:722–731. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0033OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]