Abstract

Objective

To demonstrate that Stargardt disease (STGD) can present with peripapillary atrophy.

Methods

Retrospective case series. The medical records of 150 consecutive patients (300 eyes) were reviewed retrospectively from a STGD database from January 1999 to May 2007 at Columbia University’s Harkness Eye Institute. STGD patients demonstrating peripapillary atrophy were identified.

Results

Three of 150 cases of STGD (2.0%) demonstrated peripapillary atrophy. Case 1 revealed peripapillary and central atrophy with heterozygous ABCA4 mutations P1380L and IVS40 + 5G>A. Case 2 demonstrated atrophic fleck lesions involving the peripapillary region and central atrophy with homozygous ABCA4 mutations P1380L and P1380L. Case 3 revealed bilateral central atrophy and pisciform fleck atrophy involving the peripapillary, macular, and peripheral regions with ABCA4 mutations P1380L and R2030Q. Overall, ABCA4 mutation P1380L was noted in 13 cases (8.7%), IVS40 + 5G>A in 6 cases (4.0%), and R2030Q in 1 case (0.7%). The remaining cases shared one common STGD mutation with Case 1, 2, and 3 (P1380L or IVS40 + 5G>A) and demonstrated classic STGD findings of central atrophy and varying presence of peripheral flecks without peripapillary lesions.

Conclusion

STGD can present with peripapillary atrophy. This relatively uncommon phenotype may arise from specific combinations of STGD ABCA4 mutations rather than single mutations.

Keywords: peripapillary atrophy, Stargardt disease

Stargardt disease (STGD) is the most frequent cause of inherited juvenile macular dystrophy.1 The disease is generally diagnosed before age 20 when bilateral central visual loss is first noted.2 Prognosis is generally poor and the majority of patients have visual acuities in the 20/200 to 20/400 range.1 The gene for autosomal recessive STGD, ABCA4 (ABCR), was isolated in 1997 providing means for definitive diagnosis in the majority of cases.2

Reported phenotypes resemble those of the atrophic form of age-related macular degeneration and demonstrate macular atrophy, generalized centrifugal expansion of atrophy with age, and varying presence of peripheral flecks.1–4 Recent works suggest that the peripapillary region is uniquely spared from retinal and retinal pigment epithelium degeneration and its preservation is critical for visual function in patients with large central scotomas.3,4

In this case series, we reviewed 150 cases of STGD and describe three cases with peripapillary atrophy. We also report clinical findings from additional cases of STGD that share common ABCA4 mutations.

Methods

One hundred fifty consecutive STGD patients were identified and reviewed retrospectively for peripapillary atrophy from a STGD database from June 1999 to May 2007 at Columbia University Medical Center’s Harkness Eye Institute. Two STGD patients without peripapillary atrophy who shared similar ABCA4 mutations as those with peripapillary atrophy were included in our case reports for comparison purposes.

Patients were enrolled with the approval of the Institutional Review Board (protocol #AAAB6560) at Columbia University. Genotyping was performed by the ABCR400 microarray5 followed by direct sequencing to confirm identified variants.

Case Reports

Case 1

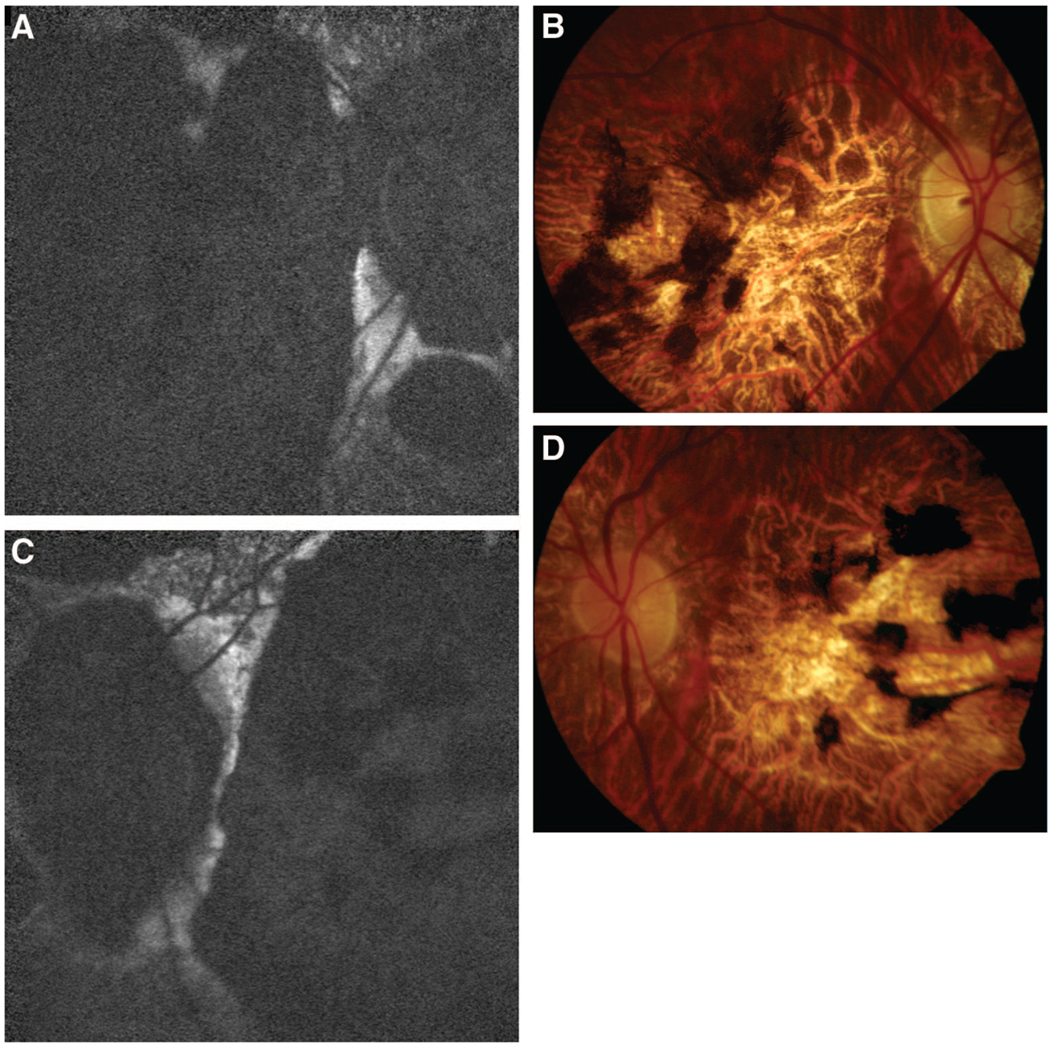

A 55-year-old male was examined for long-standing central visual impairment since age 18. Family history was not significant for ocular disease. His best-corrected visual acuity of 20/350 OD and 20/200 OS was consistent with measurements over the last 20 years. Spherical refractive error measured −3.5 OD and −2.0 OS. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable and applanation tonometry measured 17 mmHg OD and 14 mmHg OS. Posterior segment examination and autofluorescence imaging were significant for sharply demarcated central and peripapillary zones of atrophy and the absence of fleck lesions (Figure 1, A–D). Humphrey visual fields demonstrated bilateral central scotomas with eccentric fixation at the inferior border. ERG examination was subnormal and similar to results obtained 22 years ago.

Fig. 1.

Case 1. STGD with peripapillary atrophy and mutations P1380L and IVS40 + 5G>A. A, Autofluorescence OD. B, Color Photo OD. C, Autofluorescence OS. D, Color Photo OS. All show marked peripapillary and macular atrophy with a sharply demarcated zone of sparing between them. These characteristics caused initial diagnostic confusion with choroidal sclerosis.

Genetic testing was employed for further diagnostic information and two heterozygous ABCA4 mutations, P1380L and IVS40 + 5G>A, were identified and classified as disease-causing alleles, thereby confirming the diagnosis of STGD.

Case 2

A 19-year-old female referred for consultation for difficulty reading, particularly in dim light. She was clinically diagnosed with STGD 3 month prior, after complaining of gradual difficulty in focusing. Family history was not significant for ocular disease. Visual acuity measured 20/40 OD and 20/150 OS. Slit-lamp examination was unremarkable with normal anterior segments and applanation tensions of 14 mmHg OU. Funduscopic exam revealed bilateral central atrophy, multiple fleck lesions, multiple clumps of yellowish deposits at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium in the posterior pole surrounded with some pigment clumping, and no evidence of atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Autofluorescence imaging revealed multifocal atrophic lesions involving the central macula and peripheral hyperautofluorescent flecks OU. The peripapillary regions demonstrated atrophic flecks OU without confluent atrophy (Figure 2, A and B). Genotyping revealed homozygous ABCA4 mutations, P1380L and P1380L.

Fig. 2.

Case 2. STGD mutations P1380L and P1380L. A, Autofluorescence OD. B, Autofluorescence OS show multifocal hypoautofluorescent (atrophic) lesions involving the central macula OU and peripheral hyperautofluorescent flecks OU. The peripapillary regions have atrophic flecks OU but there is not confluent peripapillary atrophy.

Case 3

A 15-year-old female presented with complaints of difficulty reading materials held greater than 6 inches from her eyes. She was clinically diagnosed with STGD 4 years prior and noted decreased visual acuity since age seven, which stabilized over the past few years. Family history was not significant for ocular disease. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/150 OU. Anterior segment exam was unremarkable with applanation tonometry measuring 16 mmHg OU. Posterior segment exam and autofluorescence was significant for bilateral central atrophy and pisciform fleck atrophy involving the peripapillary, macular, and peripheral regions OU (Figure 3, A and B). Genotyping was significant for ABCA4 mutations P1380L and R2030Q.

Fig. 3.

A and B, Case 3. STGD mutations P1380L and R2030Q. Autofluorescence OD and OS demonstrate atrophic fleck lesions involving the macula and periphery with an area of confluent atrophy superotemporal to the fovea OD. Hyperautofluorescent flecks are also present in the periphery OU. The peripapillary regions reveal atrophic flecks OU without areas of confluent atrophy.

Case 4

A 52-year-old male was examined for declining vision OS over the past few months. He was previously clinically diagnosed with STGD 7 years before presentation. Family history was not significant for ocular disease. Best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/100 OD and 20/70 OS. Spherical refractive error measured −3.00 OD and −3.25 OS. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable and applanation tonometry measured 17 mmHg OD and 14 mmHg OS. Posterior segment examination was significant for central atrophy and classic peripheral pisciform flecks sparing the peripapillary regions OU (Figure 4, A and B). Autofluorescence imaging demonstrated inner atrophic flecks and outer hyperautofluorescent flecks. Moderate peripapillary hypoautofluorescence, but not atrophy, was present, likely secondary to the patient’s myopia (Figure 4, C and D). Genotyping revealed two heterozygous ABCA4 mutations, P1380L and S1696N.

Fig. 4.

Case 4. STGD mutation IVS40 + 5G>A. A, Color Photo OU. B, Red-Free Photo OU reveal central atrophy and classic peripheral pisciform flecks sparing the peripapillary regions OU. C, Autofluorescence OD. D, Autofluorescence OS show that the innermost flecks are hypoautofluorescent, consistent with atrophy, whereas the outermost flecks are hyperautofluorescent, demonstrating excess lipofuscin. There is moderate peripapillary hypoautofluorescence that is not as dark as this patient’s central atrophy or the peripapillary atrophy of Case 1. This finding may thus be due to the patient’s myopia.

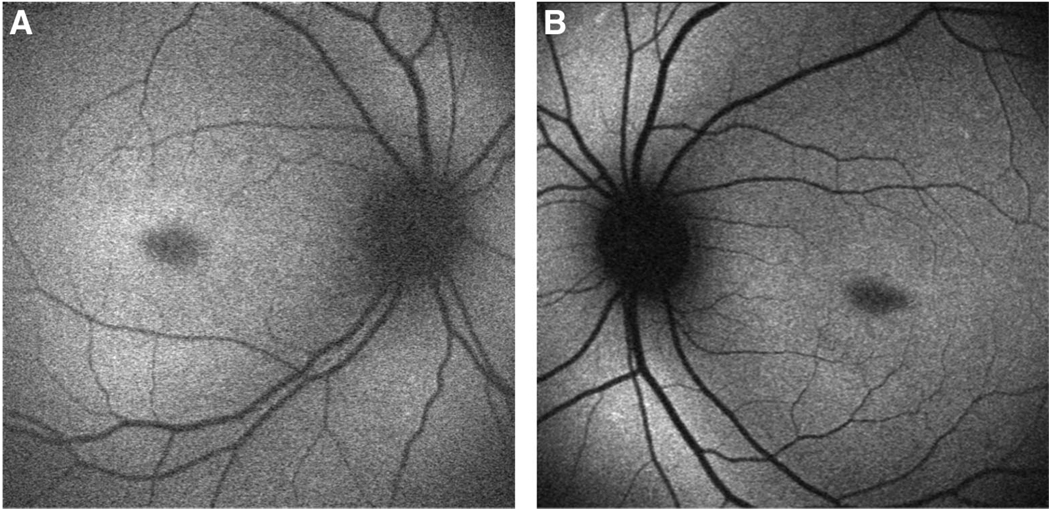

Case 5

A 46-year-old male was examined for visual acuity loss starting at age 17. His family history was significant for visual acuity loss by his brother and father during the second decade of life without known etiology. Genotype and phenotype data were not available. In addition, the patient’s son was diagnosed with STGD with symptoms beginning at age 14. Best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/400 bilaterally. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable and applanation tonometry measured 12 mmHg OD and 13 mmHg OS. Posterior segment examination and autofluorescence imaging were significant for multifocal small atrophic lesions confined to the fovea OU and normal peripapillary regions (Figure 5, A and B). Genotyping revealed a single ABCA4 mutation, IVS40 + 5G>A, confirming the diagnosis of STGD. The patient’s son was also examined and demonstrated classic STGD findings with peripapillary sparing. Genetic testing revealed a single ABCA4 mutation R1108C.

Fig. 5.

Case 5. STGD mutations P1380L and S1696N. A, Autofluorescence OD. B, Autofluorescence OS show multifocal small atrophic lesions confined to the fovea OU. The peripapillary regions are normal.

The pattern of inheritance between the father and son represents pseudo-dominant STGD. Both cases demonstrated classic STGD findings and a single identifiable mutation along with a nondetected ABCA4 mutation. The son received the nondetected mutation from the father and the identified mutation from the carrier mother, thereby accounting for the difference in genotype.

Discussion

In this series, we reviewed 150 consecutive cases of STGD and identified three cases with peripapillary atrophy (2.0%) (Table 1). Case 1 demonstrated peripapillary and central atrophy in a mildly myopic patient with ABCA4 mutations P1380L and IVS40 + 5G>A. Case 2 demonstrated atrophic fleck lesions involving the peripapillary region, central atrophy, and homozygous ABCA4 mutations P1380L and P1380L. Case 3 revealed bilateral central atrophy and pisciform fleck atrophy involving the peripapillary, macular, and peripheral regions with ABCA4 mutations P1380L and R2030Q.

Table 1.

Summary of Findings

| Case Number |

ABCA4 Mutation(s) Confirming Stargardt Disease |

Peripapillary Atrophy |

BCVA | Age of Onset (yrs) |

Duration of Disease (yrs) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD | OS | ||||||

| 1 | P1380L | IVS40 + 5G>A | Yes | 20/400 | 20/400 | 29 | 16 |

| 2 | P1380L | P1380L | Yes | 20/40 | 20/150 | 18 | 1 |

| 3 | P1380L | R2030Q | Yes | 20/150 | 20/150 | 8 | 6 |

| 4 | P1380L | S1696N | No | 20/150 | 20/70 | 45 | 7 |

| 5 | IVS40 + 5G>A | — | No | 20/400 | 20/400 | 17 | 28 |

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity.

Previous studies suggest that the peripapillary region is uniquely spared from retinal and retinal pigment epithelium degeneration.3,4 Our findings demonstrate that the clinical presentation of STGD is more variable than previously believed.

Peripapillary lesions may be attributable to specific combinations of ABCA4 mutations rather than single mutations. Many STGD cases with peripapillary preservation shared a common mutation with those cases with peripapillary atrophy. Overall, ABCA4 mutation P1380L was noted in 13 cases (8.7%), IVS40 + 5G>A in 6 cases (4.0%), and R2030Q in 1 case (0.7%). Cases 4 and 5 share common ABCA4 mutations with cases 1, 2, and 3 (P1380L or IVS40 + 5G>A), but did not yield findings of peripapillary atrophy. We were unable to find any previous reports in the literature of peripapillary atrophy in STGD, compound heterozygous ABCA4 mutations P1380L and IVS40 + 5G>A, clinical descriptions of homozygous mutations P1380L and P1380L, or clinical descriptions of compound heterozygous mutations P1380L and R2030Q.

This series also highlights the importance of genetic testing in clinical care. In Case 1, the clinical diagnosis was initially unclear and confounded by findings more consistent with choroidal sclerosis,6 including peripapillary atrophy, coarse pigment clumping, and absence of the characteristic fleck atrophy of STGD. Genetic testing provided clarity and allowed for definitive diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from The New York Community Trust (R.T.S.), Foundation Fighting Blindness (R.A.), and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York.

Footnotes

The authors have no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in any of the products or companies described in this article.

References

- 1.Rotenstreich Y, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ. Visual acuity loss and clinical observations in a large series of patients with Stargardt disease. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1151–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allikmets R, Singh N, Sun H, et al. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;15:236–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cideciyan AV, Swider M, Aleman TS, et al. ABCA4-associated retinal degenerations spare structure and function of the human parapapillary retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4739–4746. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lois N, Halfyard AS, Bird AC, Holder GE, Fitzke FW. Fundus autofluorescence in Stargardt macular dystrophy-fundus flavimaculatus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaakson K, Zernant J, Kulm M, et al. Genotyping microarray (gene chip) for the ABCR (ABCA4) gene. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:395–403. doi: 10.1002/humu.10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee TK, McTaggart KE, Sieving PA, et al. Clinical diagnoses that overlap with choroideremia. Can J Ophthalmol. 2003;38:364–372. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(03)80047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]