Abstract

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) increase neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus (DG) of rodents and nonhuman primates. We determined whether SSRIs or TCAs increase neural progenitor (NPCs) and dividing cells in the human DG in major depressive disorder (MDD).

Whole frozen hippocampi from untreated subjects with MDD (N = 5), antidepressant-treated MDD (MDDT, N = 7), and controls (C, N = 7) were fixed, sectioned and immunostained for NPCs and dividing cell markers (nestin and Ki-67 respectively), NeuN and GFAP, in single and double labeling. NPC and dividing cell numbers in the DG were estimated by stereology. Clinical data were obtained by psychological autopsy and toxicological and neuropathological examination performed in all subjects.

NPCs decreased with age (p = 0.034). Females had more NPCs than males (p = 0.023). Correcting for age and sex, MDDT receiving SSRIs had more NPCs than untreated MDD (p ≤ 0.001) and controls (p ≤ 0.001), NPCs were not different in SSRIs- and TCAs-treated MDDT (p = 0.169). Dividing cell number, unaffected by age or sex, was greater in MDDT receiving TCAs than in untreated MDD (p ≤ 0.001), SSRI-treated MDD (p = 0.001) and controls (p ≤ 0.001). The NPCs and dividing cells increase in MDDT was localized to the rostral DG. MDDT had a larger DG volume compared with untreated MDD or controls (p = 0.009).

Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cell number in the anterior human dentate gyrus. Whether this finding is critical or necessary for the antidepressants effect remains to be determined.

Keywords: Adult neurogenesis, Ki-67, nestin, major depressive disorder, SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants

Introduction

Neurogenesis has been detected in the adult hippocampus of rodents (Miller and Nowakowski 1988; Kee et al, 2002; Santarelli et al, 2003), nonhuman primates (Kornack and Rakic 1999; Gould et al, 1999) and humans (Eriksson et al, 1998). Adult neurogenesis appears to be functional since abolishing it affects hippocampal-dependent learning (Van Praag et al, 2002; Sahay and Hen 2007). In rodents, stress decreases neurogenesis while antidepressants (Dranovsky and Hen 2006), environmental enrichment, exercise (Kempermann et al, 1998; van Praag et al, 1999) and learning (Leuner et al, 2004) stimulate neurogenesis. Furthermore, some behavioral effects of pharmacologic antidepressants are blocked by abolishing dentate gyrus (DG) neurogenesis in some species (Santarelli et al, 2003; Wang et al, 2008; Surget et al, 2008; David et al, 2009). Neurogenesis decreases with age in different mammals (Rao et al, 2006; Siwak-Tapp et al, 2007; Leuner et al, 2007). The effect of fluoxetine on neurogenesis is reported to be age-dependent in Balb/c and C57Bl/6 (Navailles et al, 2008) but not 129sv mice (Santarelli et al, 2003).

Dividing cells become neurons in the granule cell layer (GCL) of the DG in the adult human hippocampus where BrdU immunoreactive (-IR) cells double-label with antibodies specific to neurons (neuron-specific enolase, calbindin, and neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN, Eriksson et al, 1998). The human DG consists of the GCL, external molecular layer (ML), and an inner polymorphic layer, the subgranular zone (SGZ, Figure 1a and b). BrdU-IR cells are localized to the SGZ and inner part of the GCL in rodents (Holick et al, 2007; Santarelli et al, 2003). In adult primates, labeled cells extend to the ML and hilus (Kornack and Rakic 1999; Gould et al, 1999). The location of BrdU-IR cells in the human brain is the same as in nonhuman primates (Eriksson et al, 1998). A cell cycle and mitosis-related protein, Ki-67 (Jakob et al, 2008), labels proliferating cells, and co-localizes with BrdU in the nonhuman primate (Gould et al, 1999) and rodent (Kee et al, 2002; Reif et al, 2006; Saravia et al, 2007) brain. In rats, BrdU co-localizes with Ki-67 over a 4-day window, making the co-localization timeframe specific (Dayer et al, 2003). In the SGZ of nonhuman primates, BrdU-IR and Ki-67-IR cell densities are positively correlated (Perera et al, 2007). Nestin is a neuron-specific intermediate filament, expressed by quiescent and amplifying neural progenitor cells (NPCs, Encinas et al, 2006; Crespel et al, 2005; Takei et al, 2007). In rodents, quiescent NPCs have a triangular soma in the SGZ and a single or double apical process that extends radially across the GCL, terminating in elaborate arbors of fine leaf-like processes in the ML. Quiescent NPCs undergo asymmetric divisions and generate the amplifying NPCs that propagate in the SGZ through a series of symmetric divisions and exit the cell cycle within one to three days becoming post-mitotic neuroblasts type 1. Unlike quiescent NPCs, amplifying NPCs do not stain for GFAP or vimentin in mice (Encinas et al, 2006). Nestin has been successfully used in human studies to detect NPCs in the brains of adults and children with temporal lobe epilepsy (Crespel et al, 2005; Takei et al, 2007).

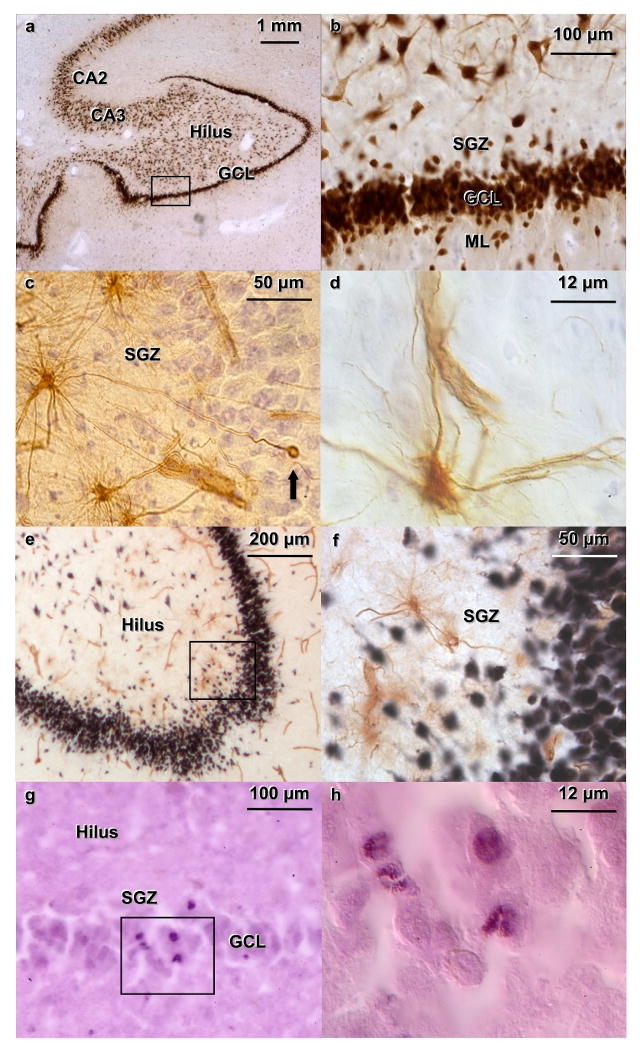

Figure 1. Immunocytochemistry for NeuN, nestin, double labeling for NeuN and nestin and immunocytochemistry for Ki-67 in human dentate gyrus (DG) from a 57 years old female control (a-f) and a 75 years old male control (g-h) who were not on medication.

(a) NeuN-immunoreactive (-IR) cells in the DG, hilus and CA regions of the hippocampus. (b) The subgranular zone (SGZ), granule cell layer (GCL) and Molecular layer (ML) are indicated; at higher magnification, the initial segments of the dendrites of the neurons of the hilus are clearly stained for NeuN (the same cells in the black box in a). (c) Nestin-IR cells (brown) along the SGZ of the DG exhibiting their characteristic multipolar appearance. Note one unipolar cell (arrow), which appears to have a higher level of differentiation, located within the GCL. Section is stained for Nissl with Cresyl Violet. (d) Differential interference contrast image of a nestin-IR cell, showing the immunostained perikarya and multiple processes, including one touching a blood vessel. (e) Double labeling of NeuN-IR granule cells (in black) and nestin-IR cells (in brown). Blood vessels are stained for nestin. (f) There is no co-labeling of Nestin and NeuN (the same cells in the black box in e). (g) Ki67-IR cells (nucleus in purple) in the GCL and SGZ of the DG. (k) Differential interference contrast image of the same cells in the black box in g. Four nuclei are labeled. After immunocytochemistry, sections were stained with eosin to label cytoplasm without interfering with the Ki-67 nuclear stain.

Impaired adult neurogenesis has been hypothesized to be part of the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder (MDD, Duman et al, 2000; Kempermann and Kronenberg 2003). Neurogenesis is impaired in stress-induced models of depression in rodents (Kempermann and Kronenberg 2003; Coyle and Duman 2003; Pham et al, 2003). However, blocking cell replication by irradiation does not induce depression-like behavior in mice (Santarelli et al, 2003). Similarly, inescapable shock decreases cell proliferation, but does not produce helpless behavior in rats (Vollmayr et al, 2003). Therefore, other factors, besides impaired neurogenesis, mediate the development of a depressive phenotype in rodents. Smaller hippocampal volume has been reported in MDD (Sheline et al, 1999; Bremner et al, 2000), together with apoptosis in neuronal cells of the entorhinal cortex, subiculum, DG, CA1, and CA4 regions of the hippocampus (Lucassen et al, 2001). However, in MDD neuron density in the hippocampus was not reduced (Stockmeier et al, 2004). Therefore it is not clear why the hippocampus might be smaller in MDD.

We determined the anatomical location within postmortem adult human DG of NPCs (Nestin-IR) and dividing cells (Ki-67-IR). We sought to test the hypotheses that antidepressant treatment increases NPC number and cell division in the human DG and that dividing cells are fewer in subjects with MDD. To assess this, we compared the number of Nestin-IR and Ki-67-IR cells in the DG from non-psychiatric controls, untreated MDD, and antidepressant-treated MDD (MDDT) who had received SSRIs or TCAs in the last three months of life.

Materials and Methods

Brain Samples

Tissue was obtained from the Brain Collection of the Human Neurobiology Core of the Conte Center for the Neuroscience of Mental Disorders and the Macedonia/NYS Psychiatric Institute Brain Collection. All research was conducted with IRB approval. Brain collection followed a standardized protocol at the time of autopsy. The right hemisphere was cut into 2 cm-thick coronal blocks, which were flash-frozen in liquid Freon (-20°C) and stored at -80°C. Samples of tissue from multiple areas of the left hemisphere were fixed in formalin for neuropathological examination. Brain pH determination (Harrison et al, 1995) and toxicological analyses were performed on cerebellar samples. Over 30 drugs were screened for and quantified if present, including: amphetamine, methamphetamine, methylphenidate, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, methadone, cocaine, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, trimipramine, maprotiline, sertraline, citalopram, chlorimipramine, diazepam, nordiazepam, 6-monacetyl morphine, paroxetine, amoxapine, heroin, olanzapine, clozapine, alprazolam, haloperidol, triazolam, buspirone and others. Samples of blood and urine were screened for alcohol, antidepressants, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabis, CO, cocaine, opioids, amphetamine, phencyclidine, salicylates and methadone. A portion of the tissue was fixed in formalin for neuropathological examination.

Subjects

Nineteen cases were studied: MDD (N = 5) without treatment for more than three months prior to death (negative toxicology); MDDT who were on SSRIs (N = 4) or TCAs (N = 3) during the three months prior to death (positive toxicology); and controls, without Axis I psychiatric disorder or history of any psychotropic medication for at least three months before death (C, N = 7, clear toxicology). Subjects (7 females and 12 males) were 17 to 62 years of age, and had a postmortem interval (PMI) of 4-24 hours. Four MDD and five MDDT cases died by suicide, one MDD and two MDDT cases died from other sudden death causes (Table 1). A psychological autopsy was used to obtain DSM-IV Axis I and II diagnoses according to the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV, APA, 1994) Life-time information on suicidal behavior, aggressive impulsive behavior, medical illness, medications, family history and developmental history was obtained (Kelly and Mann 1996). Controls inclusion criteria were death by accident, homicide or sudden natural causes, no psychiatric disorder by DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994) or history of suicide attempts, and negative toxicology for psychoactive drugs. The inclusion criteria for MDD were: Axis I diagnosis of MDD, major depressive episode within four months of death and not in remission at death, no history of treatment in the three months prior to death and negative toxicology for psychoactive drugs. Inclusion criteria for MDDT were the same as for MDD but subjects had to have a history of treatment for at least the last six weeks of life and positive toxicology for SSRIs or TCAs. Exclusion criteria for all groups were: alcohol or drug dependence or abuse as determined by the psychological autopsy, positive toxicology for alcohol, liver changes associated with alcoholism, presence of neuropathology, verdict of undetermined death, mental retardation, chronic illness that may affect CNS function (e.g., epilepsy, renal failure, metastatic malignancy, AIDS), PMI >24 hours, brain not available due to injury and resuscitation with prolonged (>10min) hypoxia.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects.

| Group | Age | Sex | PMI (h) | Brain pH | Cause of death | Axis I & II diagnosis | Toxicology | Medications prescribed (Last 3 months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 17 | Female | 22 | 6.57 | MVA-passenger | None | Lidocaine | None |

| C | 41 | Female | 15 | 6.84 | Homicide (gun shot wound) | None | Clear | None |

| C | 50 | Female | 22 | 6.94 | Peritonitis | None | Clear | None |

| C | 25 | Male | 9.5 | 6.87 | Stabbing (accident) | None | CO | None |

| C | 31 | Male | 10 | 6.24 | MVA-driver | None | Lidocaine Diazepam Tramadol | None |

| C | 34 | Male | 12 | 6.38 | Acute myocardial infarct | None | Lidocaine | Thyroxine |

| C | 53 | Male | 16 | 6.24 | Homicide (stabbing) | None | Clear | None |

| MDD | 34 | Female | 4 | 6.93 | Suicide (hanging) | MDD | Clear | None |

| MDD | 29 | Male | 15 | 6.73 | Suicide (hanging) | MDD | Clear | None |

| MDD | 29 | Male | 22 | 6.34 | Acute bronchial asthma | MDD | Theophylline | Theophylline |

| MDD | 56 | Male | 21 | 6.56 | Suicide (hanging) | MDD | Clear | None |

| MDD | 62 | Male | 21 | 6.37 | Suicide (drowning) | MDD | Clear | Lorazepam |

| MDDT*SSRI | 24 | Female | 14 | 6.87 | Suicide (fall from height) | MDD BUL/ANOR | Sertraline Bupropion | Fluoxetine Trazodone Bupropion Clonazepam |

| MDDT*SSRI | 50 | Female | 24 | 7.01 | Acute respiratory failure | MDD | Sertraline Diphenhydramine | Sertraline |

| MDDT*SSRI | 31 | Male | 6 | 6.61 | Suicide (gun shot wound) | MDD | Fluoxetine Norpropoxyphene | Fluoxetine Amitriptyline |

| MDDT*SSRI | 61 | Male | 24 | 7.14 | Suicide (fall from height) | MDD | Fluoxetine Sertraline Barbiturates Acetominophen | Fluoxetine Sertraline Barbiturates Salicylates |

| MDDT*TCA | 28 | Female | 19 | 6.32 | Suicide (fall from height) | MDD BUL/ANOR | Nortriptyline | Nortriptyline Clonazepam |

| MDDT*TCA | 38 | Male | 9 | 6.39 | Accidental overdose | MDD Cluster B PD | Clomipramine Diazepam Doxepin | Sertraline Flurazepam |

| MDDT*TCA | 61 | Male | 12 | 6.76 | Suicide (fall from height) | MDD | Nortriptyline Perphenazine | Nortriptyline Venlafaxine Sertraline Alprazolam Perphenazine |

C: Controls; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; MDDT: Treated subjects with Major Depressive Disorder; SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: Tricyclic antidepressant; MVA: Motor vehicle accident; BUL/ANOR: Eating Disorder (Bulimia, Anorexia); PD: Personality Disorder; CO: Carbon monoxide. (Subjects were assigned to the MDDT*SSRI or the MDDT*TCA group according to the drug detected in the brain toxicological exam, since medication prescribed is not necessarily taken by the patient.)

Tissue Processing

The whole hippocampal formation was dissected from two or three consecutive 2 cm-thick frozen coronal blocks. To optimize the tissue preparation, Bouins, Carnoy's, Zamboni's, paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde/paraformaldehyde fixatives were tested and 4% paraformaldehyde was selected as the most suitable for the antibodies used and for preservation of the integrity of the tissue. After one week fixation at 4°C, tissue was cryoprotected in increasing concentrations of sucrose (up to 30%), sectioned frozen at 50μm on a sliding microtome (Microm HM 440E, Walldorf, Germany), collected into 40-well boxes, each well containing a series of sections at 2 mm intervals along the anterior-posterior extent of the hippocampal formation, and stored at -20°C in cryoprotectant solution (30% ethylene glycol in 0.1-M PBS) until use.

Immunocytochemistry

We used immunocytochemistry to identify NPCs (anti-nestin mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:8,000, Chemicon, Temecula, CA); dividing cells (anti-Ki-67 mouse monoclonal antibody, Clone-MM1, 1:200, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), mature neurons (anti-NeuN mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:100,000; Chemicon) and mature astrocytes (anti-GFAP mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:9,000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Primary antibody was omitted in negative control sections. For single labeling, sections were removed from the cryoprotectant and exhaustively washed in 0.01M PBS for 60 min, then treated with 0.5% sodium borohydride to remove aldehydes, rinsed in PBS and incubated for 10 min in PBS with 3% hydrogen peroxide to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. Sets of immediately adjacent sections were processed for Ki-67 or nestin. Primary antibodies were added to blocking buffer and sections incubated over five days at 4°C. This incubation time was used to ensure full penetration of the antibody through the entire 50 μm thickness of the sections, thus allowing 3D stereological cell counting and a correct estimate of the total cell counts. As a secondary antibody, biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (1:200, Vectastain Elite ABC, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) was used. Sections were processed with ABC reagents (Vector Laboratories) and immunostaining visualized with 3′,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich). Sections immunoreacted with nestin were stained for Nissl and those assayed with Ki-67 were stained for eosin, in order to highlight neuronal elements. Sections were then dehydrated, cleared and cover-slipped. Double labeling experiments were performed to ascertain whether nestin-IR co-localized with NeuN-IR in neurons or GFAP-IR in astrocytes or QNPs, which also stain for GFAP (Encinas et al, 2006). The first antigens were visualized by the ABC reagents and 1% nickel sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.05% DAB and 0.01% H2O2 in PBS to yield a black precipitate. Then avidin and biotin were blocked using an Avidin/Biotin blocking kit (Vector SP-2001, Vector Laboratories, Jin et al, 2004) and immunocytochemistry for the second marker was performed with the same method described, but with 0.05% DAB to yield a brown precipitate. Thus, different antigens were distinguished by their color and appearance, and double-labeled cells were theoretically identifiable.

Stereology

We quantified the number of dividing cells (Ki-67-IR) and NPCs (Nestin-IR) in the DG, which included the SGZ, GCL and ML. The boundaries of the DG were initially defined at low magnification with a 1.6× objective. Sampling was performed every two mm throughout the anterior-posterior extent of the DG with a 40× objective for Nestin-IR cells and a 63× objective for Ki-67-IR cells. Reliability of counting cells with a 40× objective was obtained counting the Nestin-IR cells with a 40× and a 63× objective in two subjects. We counted 6-10 sections per case. Each immunoreacted section was matched using a Leica Wild M3Z type stereoscope (Leica Heerburg, Heerburg, Switzerland) to a near adjacent Nissl-stained section that was numbered during the sectioning protocol and served as a reference for cytoarchitectonic details. This matching allowed for accurately aligning nestin- and Ki-67-IR sections along the anterior-posterior axis of the DG. We compared the total number of nestin-IR and Ki-67-IR cells across the anterior-posterior axis of the DG in the four groups (controls, MDD, MDDT who received SSRIs, MDDT who received TCAs). To estimate the total number of nestin-IR and Ki-67-IR cells we used the optical disector approach with the fractionator method (West and Gundersen 1990; Gundersen et al, 1988; Joelving et al, 2006). The counting protocol was done with oversampling, as required when estimating the number of rare elements (Ngwenya et al, 2005). The upper and lower 3 μm in the z planes were not counted. The total number of objects counted in the individual disectors was multiplied by the reciprocals of: sampling fraction for section (SSF), area (ASF) and thickness (TSF). The sampling parameters used to estimate the total cell number were: SSF = 0.019, ASF = 0.652, TSF = 0.816. The equipment consisted of a Leica Diaplan microscope (Leitz Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a motorized stage (Ludl Electronic Products, Hawthorne, NY) and a CCD color camera (MicroFire CCD, Optronics, Goleta, CA) connected to a computer to run the stereology software (StereoInvestigator, MBF Biosciences Inc., Williston, VT). We measured the volume of the region of interest using the Cavalieri's principle, which allows obtaining an estimated volume of an object of arbitrary shape and size. The area of the region of interest within a section was determined by point counting and then the volume was calculated by multiplying the sum of the areas of the region of interest by the mean section thickness, times the distance between each section. We used the following formula:

where V is the volume, T the distance between parallel sections, A the calculated area of a section, and n the total number of sections. The first slide to be sampled was the one in which the DG first appeared and subsequent sections were measured every two mm thereafter. All sampling was done by personnel masked to the group assignment of the case.

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (16.0 for Mac). An alpha value of 0.05 was used for significance level. Different cell types, Ki-67-IR and nestin-IR, were analyzed separately. Regression analysis on log-transformed data was used to test the effect of age, PMI and pH on cell number within groups. We tested cell number and DG volume differences between MDD, MDDT on TCAs, MDDT on SSRIs and controls using ANOVA, with age as covariate when analyzing nestin-IR cells, and Tukey post hoc analysis for pair-wise comparisons. We did an age median split and used age ≤ 38 years and age > 38 years as factor in a univariate ANOVA with three between-subjects factors: age, sex and group to test the effect of sex on progenitor and dividing cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and p values are 2-tailed.

Results

Anatomical distribution of progenitor and dividing cells

Nestin-IR cells

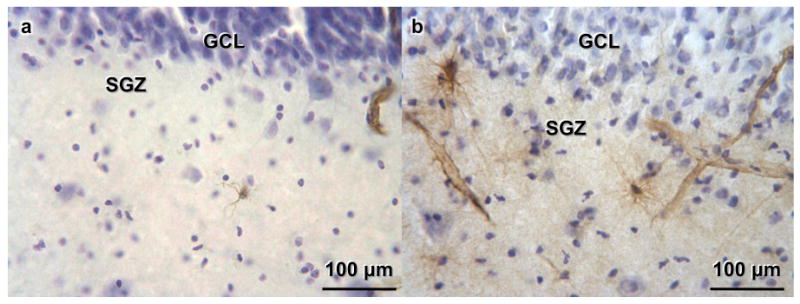

Nestin-IR cells were detected in the subgranular zone of the DG, where they can be found in niches where multiple cells appear in groups and often show connections with the vasculature (Figure 1c and 1d). They also appear isolated along the SGZ of the DG. Nestin-IR cells can also be found in the fimbria and in the sub subependymal layer, but those areas were not analyzed in this study. There were no nestin-IR cells in the ML (Figure 1e), CA regions or neocortex. The nestin antibody stains the cell's cytoplasm and processes (Figure 1d). Nestin-IR cells found in the SGZ were multipolar (Figure 1c, 1d), although, less frequently, had a unipolar appearance as they migrated into the GCL (Figure 1c, arrow). Nestin-IR cells were present throughout the SGZ, in a non-uniform pattern. They appeared distributed along the SGZ, more often in the crest of the DG (Figure 1e), sometimes in groups. Blood vessels also stained for nestin (Figures 1c, 1d, and 1e), and NPCs were found adjacent to capillaries, but only in the SGZ of the DG and not in other regions of the hippocampus. In MDDT, Nestin-IR cells exhibited prominent processes and a more complex structure than in untreated MDDs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nestin-immunoreactive (-IR) cells and vessels in the dentate gyrus (DG) from a 29 years old male with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) who was not on medication (a) and a 31 years old male MDD who was treated with fluoxetine (b).

(a) The subgranular zone (SGZ) and granule cell layer (GCL) are indicated. Cells are stained for Nissl with Cresyl Violet. Nestin-IR cells and vessels appear in brown. (b) The fluoxetine-treated MDD shows more prominent nestin-IR cells processes and vessels compared to the untreated MDD (in a).

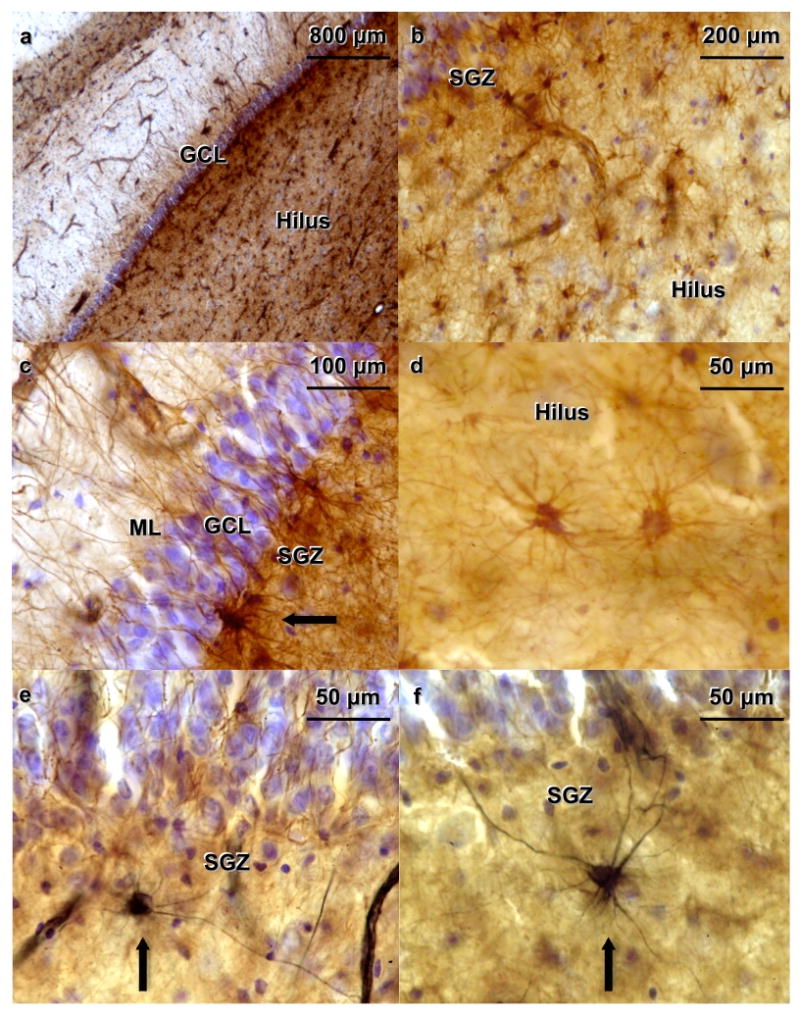

GFAP-IR cells

GFAP-IR cells were ubiquitously located throughout the hilus (Figure 3a, 3b) and the hippocampal formation. Astrocytes do not stain for nestin, but they do stain for GFAP (Figure 3c, 3d). The nestin/GFAP double labeling show GFAP labels astrocytes that are distributed in all subregions of the hippocampus (Figure 3a), including the hilus (Figure 3b), CA regions, and the adjacent neocortex. GFAP-IR cells located in the SGZ had processes that crossed the GCL and extended into the ML of the DG (Figure 3c). Two different populations of cells in human hippocampus expressed GFAP (Figure 3c, 3d) or nestin (Figure 3e, 3f). A few cells were labeled by both GFAP and nestin.

Figure 3. Human dentate gyrus (DG) treated with double-labeling immunocytochemistry for nestin and glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) and stained for Nissl substance. The subject was a 57-year-old female control with no medication.

(a) The granular cell layer (GCL) appears in blue, GFAP-immunoreactive (-IR) cells stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB) appear brown. GFAP labels astrocytes in all subregions of the hippocampus (b) GFAP-IR cells are ubiquitously located throughout the hilus. (c) GFAP-IR cells located in the subgranular zone (SGZ) show processes that extend toward the molecular layer (ML), crossing the GCL. A GFAP-IR cell is seen in the SGZ near the lower edge of the picture (arrow). (d) GFAP-IR cells in the hilus at higher magnification. Astrocytes do not stain for nestin, but they do stain for GFAP (e, f) Nestin-IR cells (in black) appear along the SGZ (arrows).

NeuN-IR neurons

NeuN-IR neurons were observed in the GCL, the hilus and the CA regions (Figure 1a). Dendrites were clearly visible at high magnification (Figure 1b). Double labeling experiments (Figure 1e, 1f) showed that nestin-IR cells never stained for NeuN (Figure 1f).

Ki-67-IR cells

Ki-67-IR cells were present in the GCL and the SGZ (Figure 1g). Ki-67 is a nuclear stain; Ki-67-IR cells were identified by a black nucleus (nickel-intensified reaction product) and a pink (eosinophilic) cytoplasm (Figure 1h). Occasionally, mitotic figures were observed.

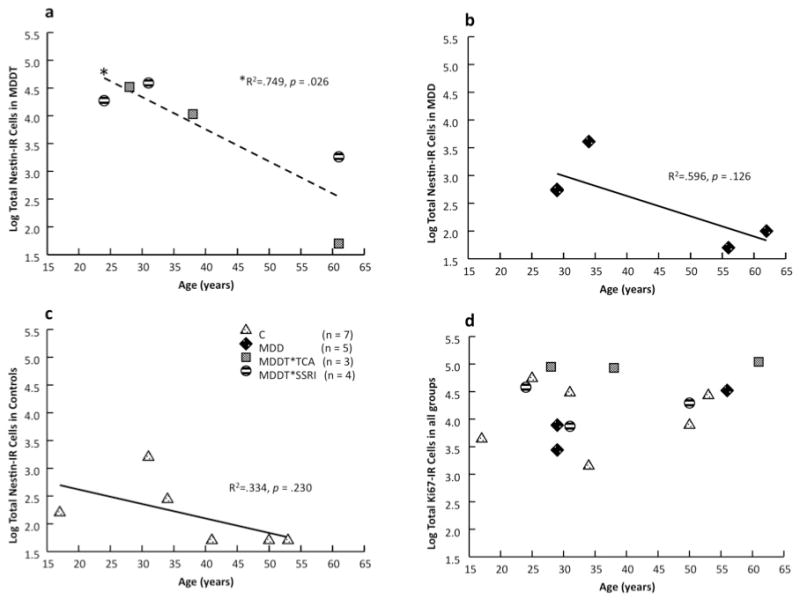

Effect of age, sex, PMI and pH on progenitor and dividing cell number and DG volume

Increasing age was associated with fewer NPCs in the MDDT group (R2 = 0.749, F = 11.966, df = 1,4, p = 0.026, Figure 4a), with MDDs and controls showing a similar, not statistically significant trend (Figure 4b and c; MDD: R2 = 0.596, F = 3.578; df = 1,4; p = 0.126; C: R2 = 0.334, F = 2.007; df = 1,4; p = 0.230). Age, used as covariate in a model comparing nestin-IR cell number between groups, was associated with fewer total NPCs (F = 5.628; df = 1,17; p = 0.034). We used an age median split (age ≤ 38 years and age >38 years) as factor in an ANOVA, including three between-subjects factors: age, sex and group. In the whole sample, age showed a significant effect, subjects ≤ 38 years old had more NPCs (13 386 ± 155; F = 1.154; df = 1,17; p ≤ 0.001) compared with subjects > 38 years old (457 ± 188). Females had more NPCs (11 183 ± 199) than males (6 682 ± 150; F = 13.034; df = 1,17; p = 0.023). To estimate the effect size of age, sex, PMI, pH, brain weight and group on NPCs and dividing cells number, we performed univariate ANOVA with covariates comparing untreated MDD with controls and with MDD treated with SSRIs or TCAs. The results are shown in Table 2.

Figure 4. Progenitor cell (Nestin-IR) number decreased with increasing age.

(a) Increasing age was associated with fewer progenitor cells (Nestin-IR) in subjects with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) who received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (MDDT*SSRI) or tryciclics (MDDT*TCA). (b, c) In controls (C) and in untreated MDD subjects, the decrease in progenitor cell number with age did not reach statistical significance. (d) Age did not affect the number of dividing cells (Ki-67-IR) in any of the groups.

Table 2. Sources of variation of neural progenitor cell (nestin-IR) and dividing cells (Ki-67-IR) number in untreated MDD compared to controls and MDD treated with tricyclics (MDD*TCA) or SSRIs (MDD*SSRI) antidepressants.

| Nestin-IR cells | MDD vs controls | MDD vs MDD*TCA | MDD vs MDD*SSRI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1,10 | P | η2 | F1,16 | P | η2 | F1,19 | P | η2 | |

| Factor | |||||||||

| Diagnosis | 27.268 | .014 | .901 | 29.666 | .012 | .908 | 8.411 | .044 | .678 |

| Sex | 10.316 | .049 | .775 | 15.007 | .030 | .833 | .243 | .656 | .075 |

| Covariates | |||||||||

| Age | 1.072 | .377 | .263 | 1.066 | .378 | .262 | 1.820 | .249 | .313 |

| PMI | 3.587 | .155 | .545 | 1.947 | .396 | .661 | 26.925 | .121 | .964 |

| pH | 2.529 | .210 | .457 | 4.203 | .289 | .808 | 1.880 | .242 | .320 |

| Brain Weight | 7.966 | .106 | .799 | 6.121 | .132 | .754 | .585 | .584 | .369 |

| Ki-67-IR cells | MDD vs controls | MDD vs MDD*TCA | MDD vs MDD*SSRI | ||||||

| F1,10 | P | η2 | F1,10 | P | η2 | F1,10 | P | η2 | |

| Factor | |||||||||

| Diagnosis | 64.476 | .077 | .985 | 1489.35 | .001 | .999 | 99.201 | .064 | .990 |

| Sex | 19.133 | .143 | .950 | .973 | .428 | .327 | 4.774 | .272 | .828 |

| Covariates | |||||||||

| Age | .044 | .869 | .042 | 8.838 | .207 | .898 | .062 | .827 | .030 |

| PMI | 3.105 | .329 | .756 | 3.035 | .332 | .752 | .328 | .625 | .141 |

| pH | 4.568 | .279 | .820 | .917 | .514 | .478 | 5.092 | .266 | .836 |

| Brain Weight | .090 | .793 | .043 | .066 | .081 | .992 | 3.349 | .318 | .770 |

MDD, major depressive disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; PMI, post-mortem interval. Numbers in bold represent significant results. Numbers in italic represent results with a trend for significance.

Dividing cells did not decrease with age in MDDT (R2 = 0.252, F = .271, df = 1,4, p = 0.630), MDD (R2 = 0.310, F = 1.348; df = 1,4; p = 0.330) or controls (R2 = 0.010, F = 0.040; df = 1,4; p = 0.852, Figure 4d) and were not different in males and females. Neither age nor sex was related to DG volume. There was no correlation between pH or PMI and NPCs, dividing cells number or DG volume in any group.

Quantification of neural progenitors and dividing cells

Nestin-IR cells

Controlling for age and sex, there were more progenitor cells in the treated MDD group (C: 360 ± 246; MDD: 1 119 ± 752; MDDT: 17 229 ± 3 443; F = 6.935; df = 3,17; p = 0.005) compared with controls and untreated MDD subjects. MDD treated with SSRIs had more progenitor cells (Figure 5a, C: 360 ± 246; MDD: 1 119 ± 221; MDDT*TCAs = 14 613 ± 271; MDDT*SSRIs = 19 844 ± 272; F = 984.105; df = 3,17; p ≤ 0.001) than untreated MDD (p ≤ 0.001) and controls (p ≤ 0.001). NPCs were not different in SSRIs- and TCAs-treated MDDTs (p = 0.169). Without controlling for age or sex, there were more Nestin-IR cells (C: 360 ± 246; MDD: 1 119 ± 752; MDDT: 17 229 ± 3 443; F = 6.935; df = 3,17; p = 0.015) in treated MDDs than in untreated MDDs (p = 0.028) or controls (p = 0.038). Dividing the treated MDD group into subjects treated with SSRIs and subjects treated with TCAs also indicated a significant difference between groups (C: 360 ± 246; MDD: 1 119 ± 221; MDDT*TCAs = 14 613 ± 271; MDDT*SSRIs = 19 844 ± 272; F = 984.105; df = 3,17; p = 0.038).

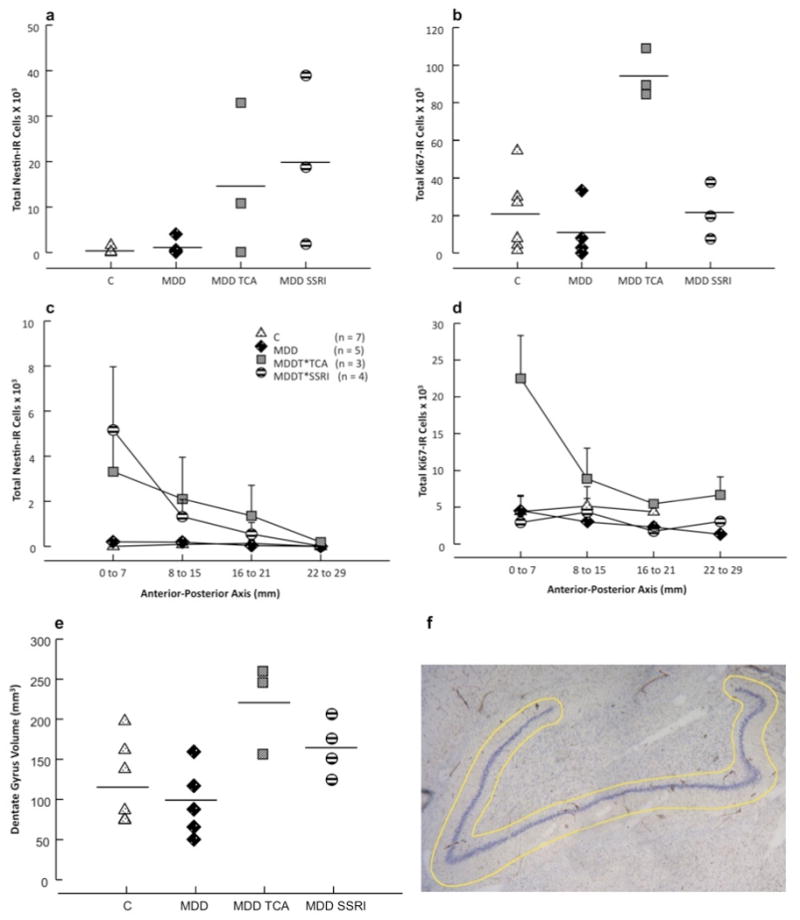

Figure 5. Neural progenitor and dividing cells are increased in the dentate gyrus (DG) of subjects with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) who were treated with antidepressants (MDDT) compared to untreated MDDs and controls (C).

(a) Progenitor cells (Nestin-IR) were higher in MDDT treated with tryciclics (MDDT*TCA), as well as in MDDT treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (MDDT*SSRI) compared to untreated MDD and C (F = 984.105; df = 3,17; p ≤ 0.001). (b) Dividing cells (Ki-67-IR) were higher in MDD*TCA compared to the other groups (F = 16.243; df = 3,17; p ≤ 0.001). (c) Number of progenitor cells (Nestin-IR) in sections located in the anterior versus posterior hippocampal formation (error bars represent S.D.) (d) Number of dividing cells (Ki-67-IR) in sections located in the anterior versus posterior hippocampal formation (error bars represent S.D.) (e) DG volume in MDDT subjects treated with TCAs was larger compared to controls and MDD (F = 5.450; df = 3,17; p = 0.010) but not different from MDDT receiving SSRIs. (f) Image of one of the hippocampus sections showing the DG stained for Nissl (in blue). The outline defines the region of interest, within which cells were counted using stereology.

Ki-67-IR cells

The number of dividing cells in the treated MDD group was about three times greater than in controls, and five times greater than in MDD (C = 20 808 ± 8 301; MDD = 10 944 ± 7 593; MDDT = 57 913 ± 17 045; F = 3.712; df = 2,17; p = 0.049). The number of dividing cells in MDDT receiving TCAs (C = 20 808 ± 8 301; MDD = 10 944 ± 7 593; MDDT*TCAs = 94 229 ± 7 494; MDDT*SSRIs = 21 597 ± 8 814; F = 16.243; df = 3,17; p ≤ 0.001) was 5.9 times higher than untreated MDD (p ≤ 0.001), 4.3 times higher than SSRI-treated MDD (p = 0.001) and 4.5 times higher than controls (p ≤ 0.001, Figure 5b). SSRI-treated MDDT subjects had a comparable number of dividing cells to controls (p = 0.812). There was half the number of dividing cells in untreated MDD compared with controls, but the difference was not statistical significant (p = 0.434).

Nestin-IR and Ki-67-IR cells distribution in the anterior vesus posterior DG

Analysis of the anterior-posterior distribution of NPCs (Figure 5c) and dividing cells (Figure 5d) in the DG revealed that the increase in cell number in the treated subjects was more prominent rostrally. Few cells were found in the most posterior hippocampal sections.

Dentate Gyrus Volume

The volume (mm3) of the DG was larger in MDDT (C = 106.3 ± 24.4; MDD = 79.6 ± 11.2; MDDT = 188.4 ± 19.1; F = 6.331; df = 2,17; p = 0.009) compared with untreated MDD (p = 0.014) and control (p = 0.033). MDDT subjects treated with TCAs (C = 115.4 ± 19.0; MDD = 96.0 ± 19.4; MDDT*TCAs = 220.6 ± 32.4; MDDT*SSRIs = 164.2 ± 34.9; F = 5.450; df = 3,17; p = 0.010) had a larger DG volume than untreated MDD (p = 0.011), and controls (p = 0.024), but not different from MDDT receiving SSRIs (p = 0.418, Figure 5e). Brain weight (grams) was not different among groups (C = 1 450.0 ± 52.9; MDD = 1 360.0 ± 88.9; MDDT*TCAs = 1 386.6 ± 63.5; MDDT*SSRIs = 1 307.5 ± 66.1; F = .637; df = 3,17; p = 0.608), as well as section thickness (μm) after processing (C = 32.0 ± 2.4; MDD = 36.7 ± 2.9; MDDT*TCAs = 28.8 ± 1.2; MDDT*SSRIs = 36.7 ± 3.1; F = 1.315; df = 3,14; p = 0.309). DG volume did not correlate with brain weight (p = 0.732) or section thickness (p = 0.218).

Discussion

We present the first evidence in the human dentate gyrus of more NPCs (Nestin-IR) and more dividing cells (Ki-67-IR) in SSRI- (sertraline, fluoxetine) or TCA- (nortriptyline, clomipramine) treated MDD compared with untreated MDD or controls. The untreated MDD group had 50% fewer dividing cells than controls, but the difference was not statistically significant. The number of NPCs decreased with age. Age was not related to the number of dividing cells. Females had more NPCs than males. Overall these results are consistent with many findings hitherto only observed in rodents.

In rodents, fluoxetine administration for 15 days does not affect division of quiescent NPCs but increases the number and symmetric divisions of amplifying NPCs (Encinas et al, 2006). The nestin-IR cells counted in the present study did not show vertical processes crossing the GCL and did not end in elaborate arbors in the ML -a characteristic of quiescent (or Type 1) NPCs, at least in rodents- but it is the appearance of the human GFAP-IR cells in this study. The human GFAP-IR cells in this study are either astrocytes (Figure 3d), which are ubiquitously located in the hippocampapal formation (Figure 3a) or have the appearance of quiescent (or Type 1) neural progenitors (Figure 3c), but they do not stain for nestin. In lower mammals, quiescent NPCs stain both for nestin and GFAP, whereas amplifying (or Type 2) NPCs stain for nestin but not for GFAP, and have the morphology of the human nestin-IR cells detected in this study (Encinas et al, 2006). We counted nestin-IR cells that were in the SGZ of the human DG and that stained for nestin but not GAFP and had the morphology of amplifying NPCs. These NPCs were often found groups of multiple cells associated with the vasculature in the SGZ of the DG, as has been previously described in rats (Palmer et al, 2000, see Figure 2 on page 484). Palmer et al, (2000) suggested this to be a niche where neurogenesis and angiogenesis are linked. Isolated nestin-IR cells were also found along the SGZ. In the human, nestin is known to be strongly expressed in newly formed vascular endothelial cells in the adult heart, pancreas and brain, and its expression decreases following cellular differentiation when nestin is replaced by other intermediate family proteins (see Salehi et al, 2008). Therefore, nestin immunostaining of blood vessels cannot solely be attributed to poor fixation of the tissue or to poor blood clearance. Additionally, we used hydrogen peroxide to remove endogenous peroxidase activity, and the same fixed tissue, immunoreacted for NeuN, and Ki-67 did not show any vessel immunoreactivity.

Given the morphological characteristics of the cells that stain for nestin, antidepressants in this study appeared to increase amplifying NPCs in human DG, consistent with rodent findings (Encinas et al, 2006). MDD subjects treated with SSRIs and TCAs had more NPCs than untreated MDD or controls. TCAs had a more robust effect than SSRIs on dividing cell number (Ki-67-IR), and SSRI-treated MDD had a comparable number of dividing cells to controls. One previous study used Ki-67 in human tissue to identify dividing cells, and did not find an effect of antidepressants on Ki-67-IR cell number in anterior human hippocampal formation (Reif et al, 2006). All the MDD subjects they studied, with the exception of one, were prescribed antidepressant medications. Unfortunately, no toxicology data were available for those subjects (Torrey et al, 2000), and thus, it is not known whether the medications prescribed were actually taken. Fluoxetine, imipramine (Santarelli et al, 2003; Malberg et al, 2000), tranylcypromine and reboxetine (Malberg et al, 2000) increase DG cell proliferation in mice and rats. Inhibition of neurogenesis blocks some behavioral effects of antidepressants (Santarelli et al, 2003), suggesting that DG cell proliferation may be a mechanism of antidepressant action (Santarelli et al, 2003; Duman 2004). Since BDNF expression increases in the GCL and CA subfields after chronic antidepressant administration (Nibuya et al, 1995; Dias et al, 2003), action of growth factors may play a role in the observed increased neurogenesis with antidepressant treatment. The functional relevance of enhanced neurogenesis in response to antidepressants in man needs to be tested by clinical studies to determine whether the increased cell proliferation is associated with symptoms improvement in MDD. In our postmortem study a significant proportion of the subjects died by suicide, raising the possibility that antidepressant treatment in the last six weeks of life produced cell proliferation but that might not have been sufficient, or not prolonged enough, or even necessary to produce a significant antidepressant effect. Moreover, since neurogenesis is not required for the behavioral effects of environmental enrichment (Meshi et al, 2006), which has antidepressant-like effects, mechanisms other than new cell birth, can produce an antidepressant effect.

The average number of dividing cells in untreated MDD was about half found in controls, but the difference did not reach statistical significance, perhaps because either there is no real difference or the modest sample size meant insufficient statistical power. Impaired adult hippocampal neurogenesis has been hypothesized to be part of the biological and cellular basis of major depression (Duman et al, 2000; Kempermann and Kronenberg 2003; Coyle and Duman 2003). Nevertheless, blocking or inhibiting cell proliferation does not induce learned helplessness in rats (Vollmayr et al, 2003) and does not affect anxiety and depression-related behaviors in mice (Santarelli et al, 2003; David et al, 2009), raising doubts about the etiological role of neurogenesis in major depression.

The increase in neural progenitors and dividing cells in MDDT was localized to the rostral hippocampus, which, in primates (Thierry et al, 2000), is interconnected with the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and nucleus accumbens. The equivalent structure in rodents (Risold and Swanson 1996; Moser and Moser 1998; Sahay and Hen 2007), is the ventral hippocampus which has been shown to be involved in anxiety-related behaviors (Sahay and Hen 2007) and to regulate the neuroendocrine responses to psychological stress (Risold and Swanson 1996; Nettles et al, 2000). Changes in neurogenesis appear to be subregion-specific fashion depending on the conditions. Adult animals performing spatial learning tasks have the highest levels of neurogenesis in dorsal hippocampus (Snyder et al, 2009). Similarly to our findings, chronic administration of an antidepressant (agomelatine) increased cell proliferation and neurogenesis specifically in the ventral DG of the rat (Banasr et al, 2006). A functional dissociation of the anterior and posterior axis of the hippocampus has been demonstrated by lesions studies in rats (Bannerman et al, 2004), and functional studies in primates (Colombo et al, 1998; Strange et al, 1999; Strange and Dolan 2001). Moreover, anterograde tracer injections studies showed that there is a topographic organization of the intrinsic connections of the DG, and that it is similar in macaque monkey (Kondo et al, 2008) and rat (Amaral and Witter 1989). The anatomical specificity of our findings bears further investigation and may link effects on hippocampal function to neuroendocrine responses to stress.

The NPCs in the DG decrease with increasing age. In rodents, neurogenesis decreases with age (Siwak-Tapp et al, 2007; Rao et al, 2006) and the effect of fluoxetine on DG proliferation is age-dependent (Navailles et al, 2008; Couillard-Despres et al, 2009). Age affects antidepressant responsiveness in depression (Keller et al, 1986). Impaired neurogenesis and unavailability of NPCs in older age could be a factor contributing to the poor antidepressant response observed in some elderly individuals. Increasing age was associated with fewer NPCs (Nestin-IR), but age did not affect dividing cells (Ki-67-IR). One possible explanation is that the pool of NPCs decrease with age, while the number of Ki-67-IR cells, which labels all dividing cells, including glial and endothelial cells, remains unaltered. Estrogens affect neurogenesis and stimulate progenitor cell proliferation (Saravia et al, 2007; Tanapat et al, 1999) and we found more NPCs in females than males, but a larger sample size is needed to confirm this observation. An effect of sex on neurogenesis would be of particular relevance to mood disorders, where sex differences are pronounced (Oquendo et al, 2007; Kessler et al, 1993).

Ki-67 appears to be a good marker for cell division in the DG and it co-localizes with BrdU in the nonhuman primate (Gould et al, 1999) and rodent (Kee et al, 2002; Reif et al, 2006; Saravia et al, 2007; Reif et al, 2006). In monkeys, there is a positive correlation between the density of BrdU- and Ki-67-IR cells in the SGZ (Perera et al, 2007). We found more Ki-67-IR cells than nestin-IR cells in every group. It is possible that a proportion of the dividing cells that we observed here are astroglia, microglia, or endothelial cells. Because of the differences in the timing of the expression of the proteins we cannot identify cells double labeled for Ki-67 and NeuN (Kee et al, 2002). Double-labeling with BrdU and NeuN was demonstrated when BrdU was injected antemortem in rodents and 75–90% of BrdU-IR cells eventually expressed NeuN (Madsen et al, 2000). Moreover, Ki-67, as BrdU is also expressed during apoptosis (Kuan et al, 2004). Therefore, Ki-67-IR cell number may not be as good a surrogate of neurogenesis as nestin-IR cell number in the human DG. In keeping with this idea we observed differences between nestin and Ki-67 both in the response to SSRIs and in the age effect. The fact that no effect of age is observed with Ki-67 could be explained by this marker labeling not only neural precursors, but all dividing cells.

The volume of the DG was larger in MDDT compared with untreated MDD and control groups. MDD treated with TCAs or SSRIs showed similar DG volume. We did not find differences in brain weight or post-processing section thickness among groups, suggesting that the observed larger DG volume in MDDT was not attributable to a larger brain or less shrinkage with fixation. Some imaging studies in vivo found smaller hippocampal volume in MDD compared to healthy controls (Sheline et al, 1999; Bremner et al, 2000; McKinnon et al, 2009) but effects of treatment are less studied. The increased DG volume in MDDT may suggest that antidepressant treatment increases total mature granule cell number, or volume of the neuropil. The animal model of stress-induced depression is associated with cell death and dendritic shrinkage in the hippocampal formation, which is reversed by antidepressant treatment (McEwen 1999; Moore et al, 2000). Inescapable foot shock caused loss of spine synapses selectively in CA1, CA3, and DG, reversed by desipramine (McEwen 1999; Moore et al, 2000). One previous study showed higher density of granule cells and glia in the DG and CA regions and smaller soma of pyramidal neurons in MDD compared with controls, suggesting that a reduction in neuropil may account for smaller hippocampal volume in MDD (Stockmeier et al, 2004). The observed larger volume of the DG and the higher NPC number in MDDT could be attributable not only to the increased neurogenesis, but also to an increase of cell survival resulting from antidepressants increasing Bcl-2 (Peng et al, 2008; Fricker et al, 2005), and BDNF (Nibuya et al, 1995; Dias et al, 2003), which also regulates cell survival (Sairanen et al, 2005; Benraiss et al, 2001). Whether potential antidepressant effects on neurogenesis or neuropil can change the hippocampus volume and how that affects the course of MDD remains to be determined.

We did not find an effect of PMI or pH on cell number. PMI could affect brain antigenicity (Lewis 2002; Li et al, 2003), and thus, immunocytochemistry, while the effect of pH on antigenicity is not known. We limited the potentially deleterious effects of PMI and pH by using samples with a PMI ≤ 24 hours and pH > 6.0.

The primary limitation of this study is the small sample size. Larger samples should be used for replication of the observations and to determine whether the changes in neurogenesis are present in untreated MDD. Also, comparing subjects who died by suicide with subjects who did not may help determine the effect of stress on neurogenesis in human. We used every protocol-eligible case at the time of the study and are collecting other cases for future studies. The possibility of a difference in MDD severity between treated and untreated MDDs should also be considered. Treated MDDs may have been more severely ill than untreated MDDs and therefore more likely to have sought or been prescribed treatment. On the other hand, the high percentage of suicide cases in the untreated MDD group raises the possibility that this group was untreated because of poor compliance or because of failure to access treatment. Finally, the fact that antidepressant exposure is associated with evidence of more neurogenesis does not mean it is the mechanism of antidepressant action. Future studies must determine whether degree of antidepressant response is linked to increased neurogenesis, and if it is, would motivate seeking new treatments that have this property.

Acknowledgments

Mihran J. Bakalian assisted with graph preparation and data management and Jennifer Lau with stereological analysis. Work was supported by PHS grants MH40210, MH62185, MH64168 and MH083862, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the Diane Goldberg Foundation and the Janssen Fellowship in Translational Neuroscience.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: The authors Maura Boldrini, Mark D. Underwood, Andrew J. Dwork, Gorazd B. Rosoklija and Victoria Arango declare that, except for income received from their primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past three years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

Dr. Rene' Hen receives compensation as a consultant for BrainCells, Inc., PsychoGenics, Inc., and AstraZeneca in relation to the generation of novel antidepressants.

Dr. J. John Mann received grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.

References

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Witter MP. The three-dimensional organization of the hippocampal formation: a review of anatomical data. Neuroscience. 1989;31:571–591. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banasr M, Soumier A, Hery M, Mocaer E, Daszuta A. Agomelatine, a new antidepressant, induces regional changes in hippocampal neurogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1087–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Rawlins JN, McHugh SB, Deacon RM, Yee BK, Bast T, et al. Regional dissociations within the hippocampus--memory and anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benraiss A, Chmielnicki E, Lerner K, Roh D, Goldman SA. Adenoviral brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces both neostriatal and olfactory neuronal recruitment from endogenous progenitor cells in the adult forebrain. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6718–6731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06718.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, Staib LH, Miller HL, Charney DS. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:115–118. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo M, Fernandez T, Nakamura K, Gross CG. Functional differentiation along the anterior-posterior axis of the hippocampus in monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1002–1005. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillard-Despres S, Wuertinger C, Kandasamy M, Caioni M, Stadler K, Aigner R et al. Ageing abolishes the effects of fluoxetine on neurogenesis. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 Jan 13; doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.147. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Duman RS. Finding the intracellular signaling pathways affected by mood disorder treatments. Neuron. 2003;38:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespel A, Rigau V, Coubes P, Rousset MC, de Bock F, Okano H, et al. Increased number of neural progenitors in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:436–450. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David DJ, Samuels BA, Rainer Q, Wang JW, Marsteller D, Mendez I, et al. Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron. 2009;62:479–493. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayer AG, Ford AA, Cleaver KM, Yassaee M, Cameron HA. Short-term and long-term survival of new neurons in the rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:563–572. doi: 10.1002/cne.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias BG, Banerjee SB, Duman RS, Vaidya VA. Differential regulation of brain derived neurotrophic factor transcripts by antidepressant treatments in the adult rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranovsky A, Hen R. Hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation by stress and antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1136–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS. Depression: a case of neuronal life and death? Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Malberg J, Nakagawa S, D'Sa C. Neuronal plasticity and survival in mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:732–739. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00935-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encinas JM, Vaahtokari A, Enikolopov G. Fluoxetine targets early progenitor cells in the adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8233–8238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601992103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker AD, Rios C, Devi LA, Gomes I. Serotonin receptor activation leads to neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;138:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Reeves AJ, Fallah M, Tanapat P, Gross CG, Fuchs E. Hippocampal neurogenesis in adult Old World primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5263–5267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJG, Bagger P, Bendtsen TF, Evans SM, Korbo L, Marcussen N, et al. The new stereological tools: Disector, fractionator, nucleator and point sampled intercepts and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988;96:857–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Heath PR, Eastwood SL, Burnet PWJ, McDonald B, Pearson RCA. The relative importance of premortem acidosis and postmortem interval for human brain gene expression studies: Selective mRNA vulnerability and comparison with their encoded proteins. Neurosci Lett. 1995;200:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12102-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick KA, Lee DC, Hen R, Dulawa SC. Behavioral Effects of Chronic Fluoxetine in BALB/cJ Mice Do Not Require Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis or the Serotonin 1A Receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;33:406–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob C, Liersch T, Meyer W, Becker H, Baretton GB, Aust DE. Predictive value of Ki67 and p53 in locally advanced rectal cancer: correlation with thymidylate synthase and histopathological tumor regression after neoadjuvant 5-FU-based chemoradiotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1060–1066. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Peel AL, Mao XO, Xie L, Cottrell BA, Henshall DC, et al. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:343–347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joelving FC, Billeskov R, Christensen JR, West MJ, Pakkenberg B. Hippocampal neuron and glial cell numbers in Parkinson's disease--a stereological study. Hippocampus. 2006;16:826–833. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee N, Sivalingam S, Boonstra R, Wojtowicz JM. The utility of Ki-67 and BrdU as proliferative markers of adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Coryell W, et al. Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:458–466. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800050064007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TM, Mann JJ. Validity of DSM-III-R diagnosis by psychological autopsy: a comparison with clinician ante-mortem diagnosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Brandon EP, Gage FH. Environmental stimulation of 129/SvJ mice causes increased cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Curr Biol. 1998;8:939–942. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Kronenberg G. Depressed new neurons--adult hippocampal neurogenesis and a cellular plasticity hypothesis of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:499–503. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Lavenex P, Amaral DG. Intrinsic connections of the macaque monkey hippocampal formation: I. Dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511:497–520. doi: 10.1002/cne.21825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack DR, Rakic P. Continuation of neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the adult macaque monkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5768–5773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan CY, Schloemer AJ, Lu A, Burns KA, Weng WL, Williams MT, et al. Hypoxia-ischemia induces DNA synthesis without cell proliferation in dying neurons in adult rodent brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10763–10772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3883-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner B, Kozorovitskiy Y, Gross CG, Gould E. Diminished adult neurogenesis in the marmoset brain precedes old age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17169–17173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708228104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner B, Mendolia-Loffredo S, Kozorovitskiy Y, Samburg D, Gould E, Shors TJ. Learning enhances the survival of new neurons beyond the time when the hippocampus is required for memory. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7477–7481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0204-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA. The human brain revisited. Opportunities and challenges in postmortem studies of psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:143–154. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gould TD, Yuan P, Manji HK, Chen G. Post-mortem interval effects on the phosphorylation of signaling proteins. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1017–1025. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen PJ, Muller MB, Holsboer F, Bauer J, Holtrop A, Wouda J, et al. Hippocampal apoptosis in major depression is a minor event and absent from subareas at risk for glucocorticoid overexposure. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:453–468. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63988-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen TM, Treschow A, Bengzon J, Bolwig TG, Lindvall O, Tingström A. Incresed neurogenesis in a model of electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9104–9110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Stress and hippocampal plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:105–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon MC, Yucel K, Nazarov A, MacQueen GM. A meta-analysis examining clinical predictors of hippocampal volume in patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34:41–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshi D, Drew MR, Saxe M, Ansorge MS, David D, Santarelli L, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis is not required for behavioral effects of environmental enrichment. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:729–731. doi: 10.1038/nn1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Nowakowski RS. Use of bromodeoxyuridine-immunohistochemistry to examine the proliferation, migration and time of origin of cells in the central nervous system. Brain Res. 1988;457:44–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GJ, Bebchuk JM, Wilds IB, Chen G, Manji HK. Lithium-induced increase in human brain grey matter. Lancet. 2000;356:1241–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser MB, Moser EI. Functional differentiation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1998;8:608–619. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:6<608::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navailles S, Hof PR, Schmauss C. Antidepressant drug-induced stimulation of mouse hippocampal neurogenesis is age-dependent and altered by early life stress. J Comp Neurol. 2008;509:372–381. doi: 10.1002/cne.21775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettles KW, Pesold C, Goldman MB. Influence of the ventral hippocampal formation on plasma vasopressin, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and behavioral responses to novel acoustic stress. Brain Res. 2000;858:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwenya LB, Peters A, Rosene DL. Light and electron microscopic immunohistochemical detection of bromodeoxyuridine-labeled cells in the brain: different fixation and processing protocols. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:821–832. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6605.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS. Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7539–7547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Bongiovi-Garcia ME, Galfalvy H, Goldberg PH, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, et al. Sex differences in clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:134–141. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer TD, Willhoite AR, Gage FH. Vascular niche for adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:479–494. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001002)425:4<479::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng CH, Chiou SH, Chen SJ, Chou YC, Ku HH, Cheng CK, et al. Neuroprotection by Imipramine against lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis in hippocampus-derived neural stem cells mediated by activation of BDNF and the MAPK pathway. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera TD, Coplan JD, Lisanby SH, Lipira CM, Arif M, Carpio C, et al. Antidepressant-induced neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult nonhuman primates. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4894–4901. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0237-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham K, Nacher J, Hof PR, McEwen BS. Repeated restraint stress suppresses neurogenesis and induces biphasic PSA-NCAM expression in the adult rat dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:879–886. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MS, Hattiangady B, Shetty AK. The window and mechanisms of major age-related decline in the production of new neurons within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Aging Cell. 2006;5:545–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif A, Fritzen S, Finger M, Strobel A, Lauer M, Schmitt A, et al. Neural stem cell proliferation is decreased in schizophrenia, but not in depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:514–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risold PY, Swanson LW. Structural evidence for functional domains in the rat hippocampus. Science. 1996;272:1484–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen M, Lucas G, Ernfors P, Castren M, Castren E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and antidepressant drugs have different but coordinated effects on neuronal turnover, proliferation, and survival in the adult dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1089–1094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3741-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi F, Kovacs K, Cusimano MD, Horvath E, Bell CD, Rotondo F, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of nestin in adenohypophysial vessels during development of pituitary infarction. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:118–123. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/01/0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, et al. Requirement of Hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravia F, Beauquis J, Pietranera L, De Nicola AF. Neuroprotective effects of estradiol in hippocampal neurons and glia of middle age mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI, Sanghavi M, Mintun MA, Gado MH. Depression duration but not age predicts hippocampal volume loss in medically healthy women with recurrent major depression. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5034–5043. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05034.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siwak-Tapp CT, Head E, Muggenburg BA, Milgram NW, Cotman CW. Neurogenesis decreases with age in the canine hippocampus and correlates with cognitive function. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;88:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JS, Radik R, Wojtowicz JM, Cameron HA. Anatomical gradients of adult neurogenesis and activity: young neurons in the ventral dentate gyrus are activated by water maze training. Hippocampus. 2009;19:360–370. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockmeier CA, Mahajan GJ, Konick LC, Overholser JC, Jurjus GJ, Meltzer HY, et al. Cellular changes in the postmortem hippocampus in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:640–650. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange BA, Dolan RJ. Adaptive anterior hippocampal responses to oddball stimuli. Hippocampus. 2001;11:690–698. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange BA, Fletcher PC, Henson RN, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Segregating the functions of human hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4034–4039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surget A, Saxe M, Leman S, Ibarguen-Vargas Y, Chalon S, Griebel G, et al. Drug-dependent requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis in a model of depression and of antidepressant reversal. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei H, Wilfong A, Yoshor D, Armstrong DL, Bhattacharjee MB. Evidence of increased cell proliferation in the hippocampus in children with Ammon's horn sclerosis. Pathol Int. 2007;57:76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanapat P, Hastings NB, Reeves AJ, Gould E. Estrogen stimulates a transient increase in the number of new neurons in the dentate gyrus of the adult female rat. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5792–5801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05792.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry AM, Gioanni Y, Degenetais E, Glowinski J. Hippocampo-prefrontal cortex pathway: anatomical and electrophysiological characteristics. Hippocampus. 2000;10:411–419. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<411::AID-HIPO7>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF, Webster M, Knable M, Johnston N, Yolken RH. The stanley foundation brain collection and neuropathology consortium. Schizophr Res. 2000;44:151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2002;415:1030–1034. doi: 10.1038/4151030a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmayr B, Simonis C, Weber S, Gass P, Henn F. Reduced cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus is not correlated with the development of learned helplessness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW, David DJ, Monckton JE, Battaglia F, Hen R. Chronic fluoxetine stimulates maturation and synaptic plasticity of adult-born hippocampal granule cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1374–1384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3632-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Gundersen HJG. Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:1–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]