Abstract

The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) is a key measure of social cognition recommended by the MATRICS committee. While the psychometric properties of the MSCEIT appear strong, previous evidence suggested its factor structure may have shifted when applied to schizophrenia patients, posing important implications for cross-group comparisons. Using multi-group confirmatory factor analysis, we explicitly tested the factorial invariance of the MSCEIT across schizophrenia (n = 64) and two normative samples (n = 2,099 and 451). Results indicated that the factor structure of the MSCEIT was significantly different between the schizophrenia and normative samples. Implications for future research are discussed.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is characterized by marked impairments in social cognition that can limit functional recovery (Couture et al., 2006). Unfortunately, measurement strategies for assessing social-cognitive impairments in schizophrenia continue to be limited (Green et al., 2004). The NIMH-MATRICS committee has recently recommended the Managing Emotions subscale of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (Mayer et al., 2003; MSCEIT) as a key measure of social cognition in schizophrenia (Green et al., 2005). Although the MSCEIT was developed among non-psychiatric populations, initial psychometric investigations with schizophrenia outpatients by our group and the MATRICS committee have documented the reliability and discriminant validity of the instrument, as well as modest cross-sectional associations with functional outcome (Eack et al., in press; Nuechterlein et al., 2008).

Despite these favorable psychometric findings, we also found reason to suspect that the factor structure of the MSCEIT may have shifted in schizophrenia patients. This has important implications for how the test is used in this population, as significant measurement variance might suggest alternative ways to score its components, limit the validity of cross-group comparisons, and change its predictive power with other constructs. Whereas the majority of studies of normative samples have identified a 4-factor/branch structure for the MSCEIT consistent with Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) model of emotional intelligence (EI; Mayer et al., 2003; Palmer et al., 2005), we found evidence for at most a 2-factor solution that was distinct from previously reported factor models (Eack et al., in press). This suggested that the latent structure of EI may be different in schizophrenia. Here we make use of confirmatory factor analysis to specifically test whether the MSCEIT is factorially invariant across a sample of schizophrenia outpatients and two large, independent normative samples.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Schizophrenia sample

Sixty-four individuals in the early course (M illness duration = 3.20, SD = 2.31) of schizophrenia (n = 37), schizoaffective (n = 23), or schizophreniform disorder (n = 4), confirmed by the SCID (First et al., 2002) and previously reported on in our initial psychometric study of the MSCEIT (Eack et al., in press), constituted the schizophrenia sample. Participants were young (M age = 25.78, SD = 6.15), and the majority were male (69%), Caucasian (67%), and had attended college (66%), although most (77%) were not employed.

2.1.2. Normative samples

Two independent normative samples collected from previous investigations of the MSCEIT were used in this research. The first sample was collected by Mayer and colleagues (2003) in an international study of academic settings with 2,112 adults throughout North America (61%), Asia (17%), Europe (11%), and Africa (11%). The sample was young (M age = 26.25, SD = 10.51), over half were Caucasian (58%) and female (59%), and most (89%) had attended college. Correlation matrices using pairwise deletion obtained from the test authors included an average of 2,099 (SD = 397) individuals for analysis. The second sample was collected by Palmer and colleagues (2005) from 451 individuals living in Australia. Participants were older (M age = 37.39, SD = 14.13), most (79%) were Caucasian, over half (62%) were female, and most (82%) had attended college. No information is available regarding the prevalence of mental illness in either of the normative study samples. However, both samples were drawn from the non-institutionalized, general population where the prevalence of schizophrenia is quite low (.3%; Kessler et al., 1994). The schizophrenia sample differed significantly from the Palmer and colleagues sample with regard to age, gender, education, and ethnicity; and differed from the Mayer and colleagues sample with regard to gender, education, and ethnicity (all p < .01). The two normative differed significantly with regard to age, education, and ethnicity (all p < .01).

2.2. Measures

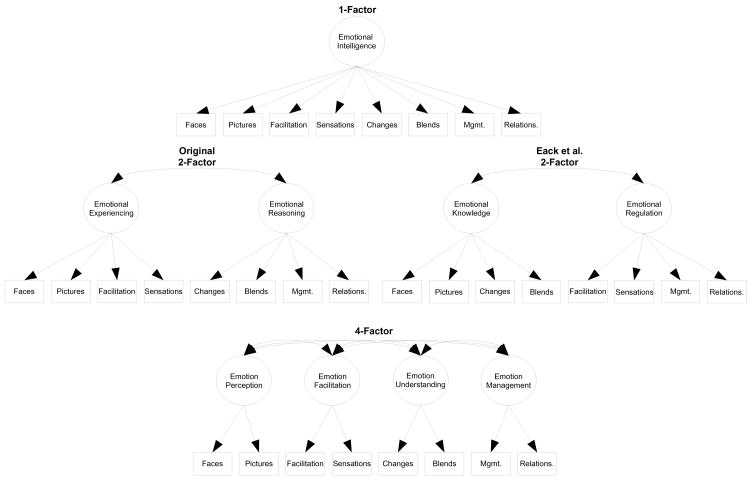

The MSCEIT is a performance-based measure designed to assess 4 branches of EI outlined by Mayer and Salovey (1997), and consists of 8 tasks based on 141 items, with two tasks forming a single branch (see Figure 1). Tasks range from identifying emotion in human faces to identifying strategies to manage emotions in social situations. Raw scores were used in all analyses as these were the only scores available from the Mayer and colleagues (2003) sample. All administrations of the MSCEIT were completed in English.

Figure 1.

Proposed Factor Models for the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test.

2.3. Procedures and Data Analysis

All data were collected cross-sectionally, and for the schizophrenia sample, prior to the initiation of treatment in a trial of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (Hogarty & Greenwald, 2006). All studies were approved by their respective Institutional Review Boards, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis on partial covariance matrices adjusting for age, gender, educational status, and ethnicity with Mplus 4.21. Analysis proceeded by first examining the fit of the most commonly supported 1-, 2-, and 4-factor models for the MSCEIT within each of the study samples based on models proposed by Mayer and Salovey (1997), as well as the novel 2-factor structure identified by Eack and colleagues (in press) among schizophrenia patients (see Figure 1). Subsequently, multi-group analyses were conducted to explicitly test the invariance of these factor structures across samples. Model fit was assessed using χ2, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). CFI values ≥ .90 and SRMR values ≤ .08 were considered indicative of well-fitting models (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

3. Results

As can be seen in Table 1, both the modified 2-factor and the original 4-factor models for the MSCEIT provided the best fit to the observed data in the schizophrenia sample. However, the 4-factor solution did not provide any significant improvement in model fit over the modified 2-factor solution. Alternatively, analyses of the 4-factor model clearly provided the best fit in both normative samples, whereas the modified 2-factor model was not acceptable in these samples. Analyses of cross-group factorial invariance indicated that there were no significant differences between the schizophrenia and normative samples in factor loadings for any of the factor models (see Table 1). However, a shift in the latent structure of the MSCEIT was evident in cross-group analyses. While a multi-group model consisting of the modified 2-factor solution in all samples provided a poor fit to the observed data (see Table 1), the modification of this model to force a 4-factor solution in the normative samples substantially improved model fit, Δχ2(8, N = 2614) = 602.20, p < .001, CFI = .98, SRMR = .03. Conversely, model fit was not improved when forcing a 4-factor solution in the schizophrenia sample, Δχ2(4, N = 2614) = 5.15, p = .272, indicating that while the 4-factor model best represents the observed data in the normative samples, the factor structure of the MSCEIT in the schizophrenia sample could be best represented by the more parsimonious modified 2-factor model described by Eack and colleagues (in press).

Table 1.

Comparison of Factor Models for the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test Across Schizophrenia and Normative Samples.

| Model | χ2 | df | p | CFI | SRMR | Model Comparisona | Δχ2 | Δdf | Δp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia Sample (N = 64) | |||||||||

| 1. 1-Factor | 43.29 | 20 | .002 | .87 | .07 | ||||

| 2. Original 2-Factor | 41.99 | 19 | .002 | .87 | .07 | 1 vs. 2 | 1.30 | 1 | .254 |

| 3. Eack et al. 2-Factor | 35.48 | 19 | .012 | .91 | .07 | 1 vs. 3 | 7.81 | 1 | .005 |

| 4. 4-Factor | 32.06 | 15b | .006 | .91 | .08 | 3 vs. 4 | 3.42 | 4 | .490 |

|

| |||||||||

| American Normative Sample (N = 2,099) | |||||||||

| 1. 1-Factor | 616.29 | 20 | < .001 | .80 | .07 | ||||

| 2. Original 2-Factor | 341.50 | 19 | < .001 | .89 | .05 | 1 vs. 2 | 274.79 | 1 | < .001 |

| 3. Eack et al. 2-Factor | 592.52 | 19 | < .001 | .81 | .07 | 1 vs. 3 | 23.77 | 1 | < .001 |

| 4. 4-Factor | 34.15 | 15b | .003 | .99 | .02 | 2 vs. 4 | 307.35 | 4 | < .001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Australian Normative Sample (N = 451) | |||||||||

| 1. 1-Factor | 98.22 | 20 | < .001 | .83 | .06 | ||||

| 2. Original 2-Factor | 71.50 | 19 | < .001 | .89 | .05 | 1 vs. 2 | 26.72 | 1 | < .001 |

| 3. Eack et al. 2-Factor | 88.99 | 19 | < .001 | .85 | .06 | 1 vs. 3 | 9.23 | 1 | .002 |

| 4. 4-Factor | 27.47 | 15b | .025 | .97 | .04 | 2 vs. 4 | 44.03 | 4 | < .001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Cross-Group Invariant Models | |||||||||

| 1. 1-Factor | 773.07 | 74 | < .001 | .81 | .07 | 15.28 | 14 | .360 | |

| 2. Original 2-Factor | 477.94 | 69 | < .001 | .89 | .05 | 22.95 | 12 | .028c | |

| 3. Eack et al. 2-Factor | 723.96 | 69 | < .001 | .82 | .07 | 6.97 | 12 | .860 | |

| 4. 4-Factor | 117.03 | 53 | < .001 | .98 | .03 | 7.39 | 8 | .495 | |

Note. CFI = Comparative Fit Index, SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Residual

For single group samples, comparisons are tests of model fit with the previous nested, best fitting model with the lowest χ2 value in the sample. For cross-group comparisons, tests are of differences in model fit between models with factor loadings constrained to be equal across samples (presented), and models with factor loadings allowed to vary across samples.

Degrees of freedom for the 4-factor model are based on a model with correlations between emotion perception and facilitation, and emotion understanding and management branches constrained to be equal, as described by Mayer and colleagues (2003).

Between-group non-invariance is due to the Australian normative sample exhibiting a significantly greater factor loading on the changes task than the schizophrenia and the American normative samples.

4. Discussion

The Managing Emotions subscale of the MSCEIT has been recommended by the MATRICS committee as a key measure of social cognition in schizophrenia (Green et al., 2004). While recent investigations have highlighted the favorable psychometrics of this instrument in schizophrenia samples (Eack et al., in press; Nuechterlein et al., 2008), factor-analytic findings have suggested that the factor structure of the MSCEIT may have shifted in schizophrenia patients. In this research we used confirmatory factor analysis to explicitly test the degree to which various factor models for the MSCEIT were invariant across schizophrenia and normative samples. Findings indicated that while the conventional 4 branch model of EI (Mayer & Salovey, 1997) provided the best representation of the factor structure of the MSCEIT in normative samples, an alternative 2-factor model representing emotional knowledge and regulation provided the best and most parsimonious solution to the schizophrenia sample. This structural shift in the MSCEIT in schizophrenia may be due to how these deficits cluster in the disorder. For example, when patients have little understanding of emotions, they may have particular difficulty in labeling perceived expressions of emotion.

While the results of this investigation are admittedly preliminary, due to the modest sample size in the schizophrenia sample and the absence of demographically-matched controls known to be free from a mental health diagnosis, the evidence increasingly suggests an alternative factor structure for the MSCEIT when applied to schizophrenia. Since the schizophrenia sample used in this research was already subject to exploratory factor analyses in our previous study (Eack et al., in press), it will be important to verify these results in independent samples, as they cannot be interpreted as strictly confirmatory. Nonetheless, these findings have several important implications, as it would appear that the emotion perception and understanding branches, as well as the emotion facilitation and management branches of the test are more strongly correlated in schizophrenia patients. This suggests that scores on a single branch (e.g., emotion management) likely reflect their factor compliment (e.g., emotion facilitation) to a great degree in schizophrenia and that investigators may only need to use two of the test branches to arrive at a valid total EI score. For example, the two tasks from the Managing Emotions branch selected by the MATRICS committee had the highest loadings on the emotion regulation factor, and thus alone probably serve as good indicators of this construct in schizophrenia patients. Emotional knowledge, which the changes and blends tasks loaded most highly on, however would not be adequately covered by these tasks. In addition, the presence of an alternative latent structure in schizophrenia suggests the MSCEIT may be functioning differently in patients than non-patients. This may invalidate cross-group comparisons, particularly between single branch scores, although the lack of significant differences in factor loadings and the adequacy of the 4-factor model in the schizophrenia sample makes this less concerning. Finally, differences in the latent structure of the MSCEIT between schizophrenia and normative samples suggests the possibility of differences in the predictive invariance of the instrument. For example, it is possible that while MSCEIT performance may contribute little to work performance in healthy individuals, test performance is more predictive of work in patients. Future research will need to make use of larger, independent, and appropriately matched samples to further elucidate the factor structure of this promising instrument and the implications of potential factorial invariance between schizophrenia and other samples.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grants MH 79537 (SME) and MH 60902 (MSK). We thank the late Gerard E. Hogarty, M.S.W. for his leadership and direction as Co-Principal Investigator of this work, and Deborah Greenwald, Ph.D., Susan Hogarty, M.S.N., Susan Cooley M.N. Ed., Anne Louise DiBarry, M.S.N., Konasale Prasad, M.D., Haranath Parepally, M.D., Debra Montrose, Ph.D., Diana Dworakowski, M.S., Mary Carter, Ph.D., and Sara Fleet, M.S. for their help in various aspects of the study.

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this research was provided by NIMH grants MH 79537 (SME) and MH 60902 (MSK). The NIMH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

Mr. Eack, Dr. Pogue-Geile and Dr. Keshavan designed the study. Mr. Eack conducted the analyses. Mr. Eack and Dr. Pogue-Geile wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and Drs. Greeno and Keshavan provided critical revisions and feedback on both the manuscript and analyses. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The Functional Significance of Social Cognition in Schizophrenia: A Review. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(Suppl1):S44–63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Greeno CG, Pogue-Geile MF, Newhill CE, Hogarty GE, Keshavan MS. Assessing social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Schizophrenia Bulletin. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn091. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview For DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, Barch DM, Cohen J, Essock S, et al. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: The NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(5):301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Olivier B, Crawley JN, Penn DL, Silverstein S. Social cognition in schizophrenia: Recommendations from the measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia new approaches conference. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(4):882–887. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP. Cognitive Enhancement Therapy: The Training Manual. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: Authors; 2006. Available through www.CognitiveEnhancementTherapy.com. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;3(4):424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mcgonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III--R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P. What is emotional intelligence? In: Salovey P, Sluyter D, editors. Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators. New York: Basic Books; 1997. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion. 2003;3(1):97–105. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese FJ, III , Gold JM, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, Part 1: Test Selection, Reliability, and Validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BR, Gignac G, Manocha R, Stough C. A psychometric evaluation of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test Version 2.0. Intelligence. 2005;33(3):285–305. [Google Scholar]