Abstract

B- and T-lymphocytes develop from hematopoietic stem cells through a series of intermediates with progressively decreased lineage differentiation potential. Differentiation is preceded by increased accessibility of the chromatin at genes that are poised for expression in the progeny of a multipotent cell. During the process of differentiation there is increased expression of lineage-associated genes and repression of lineage inappropriate genes resulting in commitment to differentiation through a specific lineage. These transcriptional events are coordinated by networks of transcription factors and their associated chromatin remodeling factors. The B-lymphocyte lineage provides a paradigm for how these events unfold to promote specification and commitment to a single developmental pathway.

Introduction

Over the past few years, significant advances have been made in our understanding of the cellular and molecular events associated with differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) toward the lymphoid lineages. Seminal studies from the Weissman lab led to the identification of progenitor cell populations that are restricted in their developmental potential to the lymphoid (common lymphoid progenitor/CLP) or myeloid (common myeloid progenitor/CMP) lineages [1,2]. Gene expression analysis showed that these cells express low levels of transcripts for multiple lymphoid or myeloid genes respectively, a phenomenon known as “lineage priming” [3]. This low level of gene expression is thought to be the consequence of an open chromatin structure surrounding genes that need to be accessible leaving them poised to be activated in the progeny of these multipotent cells [4]. Further lineage differentiation is associated with an amplification of lineage-appropriate genes and repression of lineage-inappropriate genes through alterations in transcription factor and chromatin remodeling activities. These processes are known as lineage specification (turning on of lineage specific gene programs) and lineage commitment (repression of lineage inappropriate gene programs and concomitant restriction of alternative lineage differentiation potential).

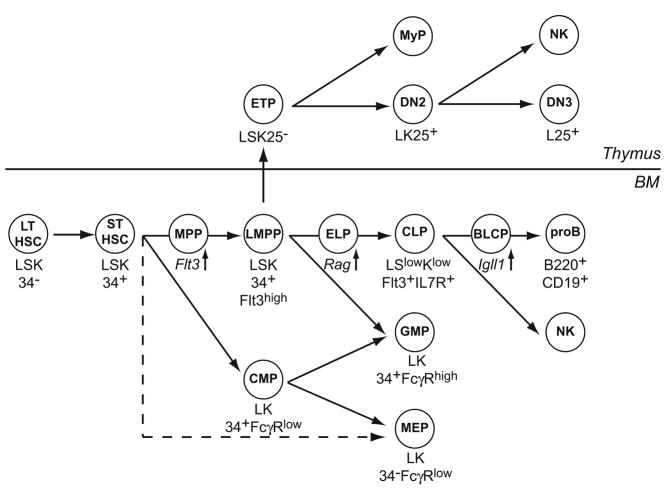

CLPs and CMPs arise from a multipotent population defined by the lack of lineage-associated receptors with high expression of Sca-1 and c-kit (Lin−Sca1+c-kit+, LSK) that contains self-renewing HSCs as well as non-self-renewing multipotent progenitors (Figure 1). Recent studies have challenged the view that all LSKs are common myelo-erythroid and lymphoid progenitors and that the first lineage restriction event results in segregation of progenitors into myelo-erythroid or lymphoid restricted cells (reviewed in [5]). These studies revealed that within LSKs there is an initial loss of megakaryocyte (Mk) and erythrocyte (E) potential as cells exit the self-renewing HSC population [6,7]. More differentiated LSKs, which express high levels of the Flt3/Flk2 receptor, retain lymphoid and granulocyte/macrophage progenitor (GMP) potential and have been termed lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs) or granulocyte/macrophage lymphoid progenitors (GMLP) [6,7]. LMPPs include lymphoid-biased progenitors such as early lymphoid progenitors (ELPs), defined by expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein from the Rag1 gene [8]. LMPPs prime lymphoid and G/M genes but Mk/E genes are not readily detected, a finding that is consistent with their developmental potential [9* ]. LMPPs are the precursors of CLPs and early thymic progenitors (ETPs) in which critical transcriptional events leading to B-cell and T-cell lineage specification and commitment occur. In this review we discuss the transcriptional regulatory pathways recently revealed to be associated with progression of HSCs toward the lymphoid lineages and we relate these findings to known networks influencing specification and commitment to the B- and T-lymphocyte fates.

Figure 1.

Precursor-progeny relationships in lymphopoiesis. HSCs with long-term (LT) and short-term (ST) self-renewal capacity generate cells of all hematopoietic lineages. Lymphoid specification is initiated as cells progress through the multipotent progenitor (MPP) and LMPP stage, concomitant with the up-regulation of Flt3 and loss of Mk/E differentiation potential. Mk/E progenitors (MEPs) may arise directly from the HSC pool. LMPPs are proposed migrate to the thymus where they differentiate into ETPs and generate specified DN2 and committed DN3 T-cells. In the BM, LMPPs further up-regulate lymphoid genes, namely Rag1 in ELPs and IL-7Rα in CLPs, and restrict G/M progenitor (GMP) potential. As B-cell differentiation progress, CLPs lose NK-cell potential. EBF1 activity, as evaluated by the expression of Igll1 (λ5), promotes B-lymphocyte commitment (BLCP) and differentiation to the pro-B cell stage. Surface markers that characterize, and allow for the isolation of, each population are indicated; L, Lineage (note that different lineage cocktails are used in the identification of different progenitors); S=Sca1; K=c-kit; 34=CD34; 25=CD25; MyP=myeloid progenitors; NK=NK lineage progenitors.

Exit from the HSC pool

Self-renewing HSCs are largely quiescent but those that divide produce two identical daughter cells. In contrast, the decision to differentiate is associated with increased proliferation and production of progeny with limited self-renewal capacity. Multiple transcription factors function to maintain the balance between self-renewal, differentiation and proliferation, including factors required for lymphocyte development such as Ikaros and Gfi1 [10–12]. The E2A transcription factors repress HSC proliferation indicating that they may also function in maintaining HSCs [13**]. How these factors participate in both HSC maintenance and lymphoid differentiation has not been determined but is likely the consequence of distinct transcriptional environments in the relevant cells including the availability of cooperating transcription factors, co-activators and co-repressors and the state of chromatin accessibility at essential target genes. Interestingly, multiple lymphoid genes have an “open” chromatin conformation in LSKs that is “closed” as cells differentiate along the myeloid lineage [14], suggesting that changes in chromatin state may facilitate differentiation. Consistent with this idea, the chromatin remodeler Mi-2β, which can interact with Ikaros and E-proteins, was recently shown to restrict HSCs from exiting the self-renewing stem cell pool presumably by maintaining a stem cell chromatin signature (Figure 2) [15**]. In the absence of Mi-2β several stem cell-associated genes are down-regulated including Mpl, which is critical for maintaining HSC quiescence [16], and the transcription factor Egr1, which restricts HSC proliferation and promotes HSC/bone marrow (BM) niche interactions [17]. In the absence of Mi-2β there is increased priming of lineage-associated transcripts including Rag1 and β-globin. Therefore, Mi-2β plays an essential role in maintaining the proper chromatin context in HSCs allowing for expression of genes necessary for stem cell behavior and preventing lineage-priming. It has been proposed that differentiation toward the lymphoid fates may require alterations in chromatin structure that facilitate lymphoid-priming in an otherwise myeloid-leaning HSC population [18*].

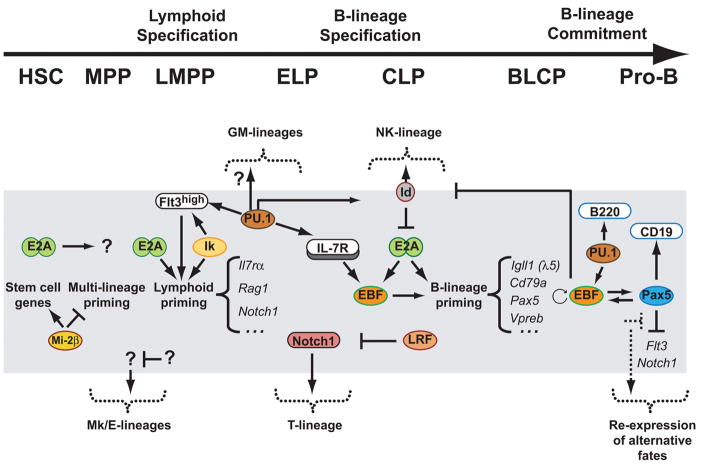

Figure 2.

Transcriptional networks in B-cell specification and commitment. Transcriptional events are shown as cells progress from HSC to committed pro-B-lymphocytes. Alternative fates are depicted outside the grey box; transcription factors are represented with circle or oval borders while surface molecules are rod shaped. The connectors do not represent obligatory effector/target relationships.

From HSC to LMPP

The identification of LMPPs as progenitors with combined lymphoid and G/M potential has been taken as compelling evidence that loss of Mk/E potential is the earliest restriction event of HSCs [5]. This restriction step involves dramatic alterations in gene expression with down-regulation of Mk/E genes (including Gata-1, Gata-2, Mpl, Scl/Tal1, Gfi1b) and priming of lymphoid genes (including Dntt, Rag1, and Il7rα), and is concomitant with the up-regulation of surface Flt3 [6,9*]. Signaling through Flt3 may play a role in the homeostasis of LMPPs since Flt3high LSKs (i.e. cells with the LMPP phenotype) fail to develop in Flt3-ligand−/− mice and there is a failure of lymphoid-priming [19]. However, low levels of Flt3 may be sufficient for development of functional LMPPs since Ikaros−/− mice develop Flt3low LSKs that have G/M and lymphoid differentiation potential [20*]. LMPPs were revealed in these mice using an Ikaros promoter-driven GFP transgene whose expression is high in LMPPs but not HSC [20*]. Taken together these data suggest that Ikaros is necessary for efficient Flt3 expression but that low levels of Flt3 are sufficient to allow development of LMPPs. How Flt3 signaling contributes to development of LMPPs remains to be determined. Another factor required for proper Flt3 expression is Pu.1, which also functions in development of early lymphoid and myeloid progenitors; however, its precise role in development or function of LMPPs remains to be investigated [21].

Our laboratory reported an essential role for the E2A transcription factors in development of LMPPs, although E2A is dispensable for Flt3 expression and restriction of the Mk/E fate (Table 1) [13**]. Priming of a few lymphoid genes can be detected in HSCs and at least a subset of these genes, along with additional HSC genes, are dependent on E2A [13**,14]. Which combination of these genes is necessary for development of LMPPs remains to be determined. However, the few LMPPs that develop in E2A−/− mice have an altered transcriptome characterized by increased expression of non-lymphoid genes paralleled by compromised lymphoid-priming and an increased potential for G/M differentiation [13**]. Surprisingly however, essential lymphoid transcription factors such as Ikaros, Pu.1 and Gfi1 are expressed in E2A−/− LMPPs even though some of their target genes fail to be primed. Therefore, E2A likely cooperates with these transcription factors to promote further lymphoid differentiation. Indeed, even though Ikaros is not essential for development of LMPPs, it is required for further lymphocyte differentiation from this population, as is Mi-2β [15**,20*]. These findings indicate that differentiation of LMPPs is likely to require the combinatorial input of multiple transcriptional regulators including activators and repressors and their associated chromatin remodeling complexes such as Mi-2β and p300/CBP.

Table 1.

Summary of Functions of Transcription Factors Discussed in this Review.

| Transcription factors influencing HSCs through LMPPs | |

| Mi-2β | Conditional KO reveals expansion and exhaustion of HSCs and premature lineage-priming |

| E2A | KO shows augmented HSC, MPP and LMPP proliferation, reduced development of LMPPs and their progeny (CLPs and ETPs) and a failure of lymphoid lineage-priming |

| Gfi1 | KO reveals defective self-renewal of HSCs and few LSKs |

| Ikaros | KO has reduced HSC self-renewal, fails to up-regulate Flt3 but develops LMPPs with altered potential for subsequent lymphoid differentiation |

| Transcription factors influencing LMPPs to committed pro-B-lymphocytes | |

| E2A | KO has few CLPs that fail to give pro-B-lymphocytes. E2A regulates Ebf1 and functions synergistically with EBF1 and other B-cell transcription factors to activate many B-cell lineage genes |

| EBF | KO has no committed pro-B cells. EBF1 regulates Pax5, cooperatively regulates multiple B-cell lineage genes and participates in lineage commitment by antagonizing myeloid gene expression |

| Pax5 | KO has pro-B-lymphocytes that are not B-cell lineage committed and can give rise to alternate lineages. Pax5 represses non-B-cell genes such as Notch1 but also promotes Ebf1 expression. No pre-B-cells or B-cell later stages develop in the absence of Pax5. |

| Stat5 | Activated by IL-7R signaling and promotes Ebf1 expression. Constitutively active Stat5 rescues pro-B- cell development from IL7rα-deficient CLPs. |

| PU.1 | Promotes Il7rα and Ebf1 expression.. |

| LRF | Conditional deletion of LRF resulted in a failure of B-cell development and ectopic T-cell development in the bone marrow. LRF appears to antagonize Notch signaling in bone marrow progenitors. |

| Transcription factors influencing LMPPs to committed DN3 thymocytes | |

| Notch1 | Notch1 signaling promotes T-cell specification and inhibits B-cell development. Notch signaling is required for T-cell lineage associated increased in Gata3 and Tcf1 expression. The mechanism of B-cell inhibition is controversial but has been hypothesized to involve antagonism of E2A, EBF or Pax5. Notch1 also prevents PU.1 and Gata3 from activating non-T-cell gene programs. |

| E2A | Required for optimal numbers of ETPs, DN2 and DN3 thymocytes. Regulates Notch1 expression and synergizes with Notch signaling to activate T-cell genes such as Hes1 and pre-Tα. |

| Gfi1 | KO has reduced numbers of ETPs and increased expression of Id proteins (E2A antagonists) |

| Tcf1/Lef1 | Expression in DN2 thymocytes is Notch-signaling dependent but the requirements for these transcription factors are unclear. Double KO has defect at a later stage of development (immature CD8+ stage) |

| CBFβ | KO has reduced T-cell development, reduced expression of Gata3 and TCF1 and phenotype is not rescued by ectopic Notch signaling |

| PU.1 | Expression decreases in T-cells after the DN2 stage. Forced expression prior to the DN3 stage results in diversion of cells to the dendritic or monocytic lineages. |

| Gata3 | Lack of function models reveal essential role for Gata3 in T-cell development. Ectopic expression causes death of DN3 thymocytes and acquisition of the mast cell fate in the absence of Notch signaling. |

From LMPPs to CLPs

The development of CLPs is associated with the loss of G/M potential and increased expression of multiple lymphoid genes. Analogous to Flt3 on LMPPs, surface expression of the interleukin (IL)-7 receptor is the hallmark of CLPs [1]. In addition, genes associated with committed B-cells, which were not primed at the LMPP stage, begin to be expressed including the essential transcription factor EBF1 and known targets of EBF1 and E2A. CLPs have many characteristics of committed pro-B-lymphocytes but they express only low levels of Pax5, which is essential for commitment to the B cell fate, and they do not express the Pax5 target gene CD19 [22]. Consistent with the absence of functional Pax5, CLPs retain natural killer (NK) cell and T-cell developmental potential; however, it remains controversial whether CLPs are necessary precursors for NK cells or T-lymphocytes in vivo [23]. In the BM, the T cell potential of multipotent progenitors is actively inhibited by the transcriptional repressor LRF (Zbtb7a), which prevents activation of the Notch signaling pathway, that is essential for T-cell development [24*]. As seen with ectopic Notch signaling, deletion of LRF allows T-cell development in the BM whereas B-cell development is severely compromised. Importantly, B-cell development can be rescued by inhibiting Notch signaling but not by ectopic expression of EBF1. However, once Pax5 is expressed Notch1 mRNA is repressed and committed pro-B-cells can no longer be diverted to the T-cell fate by ligation of cell surface Notch1 [25].

Interestingly, a recent report by Mansson et al. demonstrated that a small subset of CLPs (called BLCP), identified by expression of the EBF1 target gene Igll (λ5), has extinguished expression of T-cell and myeloid genes and is functionally committed to the B-cell fate [26]. This observation is consistent with the prevailing view that CLPs are the progeny of LMPPs that are in the process of restriction to the B-cell fate.

B-cells as a paradigm for transcriptional networks in specification and commitment

The transcriptional regulatory network that leads to specification and commitment to the B-lymphocyte lineage from CLPs remains one of the most extensively studied and best understood. Central to this process is the activation of the transcription factors EBF1 and Pax5 (reviewed in [22]). Ebf1 transcription is initiated by E2A and IL-7R-dependent Stat5 but reinforced by EBF1, PU.1 and Pax5, which is a target of EBF1 (Figure 2). These factors work on two distinct promoters that both lead to expression of a functional EBF1 protein [27*]. EBF1 collaborates with E2A and Pax5, and likely many other transcription factors such as Sox4 and Bcl11a, to activate B-lymphocyte-associated genes. Pax5 is a critical factor for commitment to the B-lymphocyte fate since loss of Pax5, even in mature B-lymphocytes, allows for de-differentiation and re-acquisition of alternative lineage potentials [28**]. A recent study suggests that Pax5 may function, at least in part, through its ability to stabilize EBF1 expression since Ebf1−/− hematopoietic progenitor cell lines also show multilineage differentiation that is repressed by ectopic expression of EBF but not Pax5 [29**]. In addition, EBF1 can suppress myeloid gene expression and myeloid differentiation in Pax5−/− pro-B-lymphocytes [29**]. One possible mechanism through which EBF1 may reinforce the B-cell fate is through suppression of the E2A antagonist Id2, a protein hypothesized to allow alternative cell fates to develop from CLPs by blocking E2A-dependent activation of B-lymphocyte genes such as EBF1. However, a recent study indicates that Id3 may functionally compensate for loss of Id2 in this process and therefore B-lymphocyte lineage specification may require repression of both Id-proteins [30]. These studies establish a paradigm in which a small number of transcription factors function in feed-forward and feed-back loops to reinforce each others’ expression thus cooperatively inducing lineage specification while concomitantly repressing alternative lineage gene programs and developmental potentials.

Development of early thymic progenitors (ETPs)

T-lymphocytes develop in the thymus and utilize both overlapping and distinct transcription factors and signaling pathways compared with B-lymphocytes (reviewed in [31]). While these two lymphocyte sub-types clearly share a common progenitor, the precise stage of differentiation where their fates diverge has been controversial [23]. CLPs give rise to T-lymphocytes when injected into the thymus or placed in appropriate in vitro cultures that support T-cell development. However, their designation as T-cell progenitors has been challenged by the finding that LMPPs also express the chemokine receptors necessary for trafficking to the thymus, and sustain a greater production of thymocytes when injected intrathymically than CLPs [32–34]. Recent data also suggest that ETPs retain myeloid potential indicating that they are not the progeny of CLPs but rather of earlier progenitors that have not yet extinguished the GMP fate [35**,36**]. Interestingly, ETPs fail to differentiate into B-lymphocytes in vitro indicating that signals delivered to these cells upon thymic entry lead to rapid extinction of the B-cell fate, yet a slower loss of myeloid and NK cell potential. Notch1 receptor signaling is critical for extinction of the B-cell fate and initiation of T cell differentiation, including the initial up regulation of multiple transcription factors required for T cell development including Gata3 and TCF1. The mechanism by which Notch1 represses B-cell potential has been controversial although repression of E2A proteins or other essential B-cell transcription factors such as EBF1 or Pax5 has been proposed [31,37].

T-lymphocytes, do they fit the paradigm?

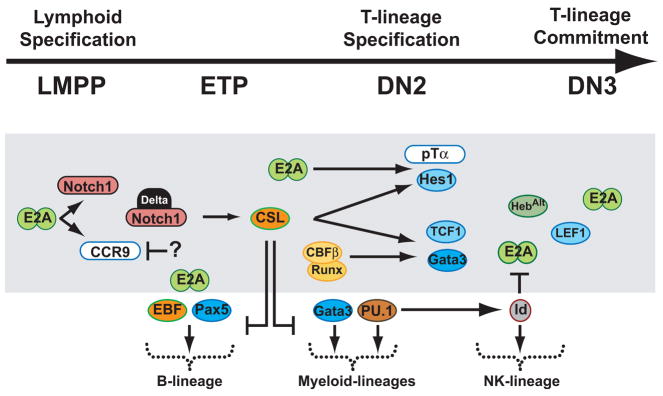

Multiple transcription factors are required for T-cell development and might play a role in lineage specification and commitment (Figure 3) [31]. However, unlike in B-cells, much less is known about how any of these factors are regulated or how they function. The E2A transcription factors are necessary for proper development of ETPs, although their primary function appears to be in the generation of BM precursors that seed the thymus [13**]. However, E2A regulates Notch1 expression and cooperates with the Notch1-activated transcription factor CSL to promote both Hes1 and pTα transcription [13**,38*]. Therefore, E2A proteins play a role in the initiation of T-cell development. Another E protein, HebALT is induced by Notch signaling in multipotent progenitors and, when ectopically expressed, increases the number of T-cells produced in vitro [39]. Other factors such as TCF1, LEF1 and Gata3 are induced as cells enter the T-cell pathway in a Notch1-dependent manner and are essential for T-cell progression, although their essential targets are not well described [40,41]. The Runx-associated transcription factor CBFβ is required, in addition to Notch1, for expression of Gata3 and progression through the early stages of T-cell development [42]. Nonetheless, additional experiments will be necessary to determine the network of interactions that lead to stable expression of these essential factors.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional networks in T-cell specification and commitment. Transcriptional events are shown as cells progress from LMPPs to committed DN3 thymocytes. Alternative fate are depicted outside the grey box; transcription factors are represented with circle or oval borders while surface molecules are rod shaped. The connectors do not represent obligatory effector/target relationships.

During T-cell development a stage can be identified where cells are in the process of T-cell lineage specification but are not yet fully committed since they retain NK cell potential (the DN2 stage, somewhat analogous to CLPs during B-cell development). At this stage, PU.1 needs to be repressed to allow progression to the fully committed DN3 stage. Forced expression of PU.1 prior to the DN3 stage results in a failure of T-cell development and, in the absence of Notch signaling, these cells can be diverted into the macrophage or dendritic cell pathways [43–45**]. In the presence of Notch signaling these cells undergo apoptosis, potentially as a consequence of repression of essential T-cell transcription factors such as TCF1 and E2A. These studies indicate that Notch1 plays a critical role in preventing the acquisition of non-T-cell fates in specified T-cell progenitors. While the mechanism by which Notch1 restricts the DN2 cell developmental options is not known, it may involve repression of the E2A antagonist Id2 since Id2 is induced by Pu.1 but only in the absence of Notch signaling [44*]. Another recent report from the Rothenberg lab highlights the critical role of Notch1 in repressing alternative developmental fates in specified T-cell progenitors and indicates a critical role for transcription factor dose in differentiation decisions. In this case, it was shown that high levels of Gata3, achieved by ectopic expression from a retroviral vector, are detrimental for T-cell development and reveals new developmental options in DN2 cells [46**]. However, in the presence of Notch signaling Gata3high DN2 cells do not exercise their capacity to develop into mast cells but simply fail to undergo T-cell commitment. This finding strengthens the hypothesis that Notch signaling represses non-T cell fates at this stage of development, which can be activated by high expression of Gata3 or Pu.1. However, it remains to be determined whether Gata3 can ever reach such high levels under physiologic conditions and whether there are mechanisms to control the expression of Gata3. Nonetheless, these studies demonstrate that factors that promote T-cell specification can also activate non-T-cell gene programs and that commitment to the T-cell lineage requires active suppression of these activities. Taken together, the process of T-cell development appears to involve both the activation of T-cell gene programs (specification) and repression of non-T-cell gene programs (commitment) but the mechanism by which the essential transcription factors achieve these goals may differ from those in the B-cell developmental program.

Conclusions

The process of lymphocyte development from HSCs is characterized by the broad priming of lineage-associated genes followed by reinforcement of specific gene programs and repression of inappropriate gene programs. Over the next few years we anticipate that the factors required to extinguish Mk/E potential or for initiating lymphoid differentiation from HSCs will be identified and novel mechanisms for controlling chromatin dynamics during this differentiation process will be revealed. In addition, the network of transcriptional regulators controlling T-cell lineage specification and commitment should also be defined. Studies of T-cell lineage commitment may reveal novel mechanisms for achieving the committed state and it will be of interest to determine whether general principles can be identified and applied to other lymphoid lineages such as NK cells. Establishing these general principles may allow us to understand how alterations in these processes lead to disease such as leukemia and immune-deficiency and how to manipulate this system for therapeutic gain in bone marrow transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Work in our laboratory was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 CA99978) and ACS. S. Dias was supported by a training grant from the Committee on Cancer Biology at the University of Chicago; S. Graves is supported by the Medical Scientist Training Program. B.L. Kee is a Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. We thank F. Gounari for comments on this manuscript. We apologize to all of our colleagues whose work could not be cited directly here due to space limitations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogneic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyamoto T, Iwasaki H, Reizis B, Ye M, Graf T, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Myeloid or lymphoid promiscuity as a critical step in hematopoietic lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2002;3:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kioussis D, Georgopoulos K. Epigenetic flexibility underlying lineage choices in the adaptive immune system. Science. 2007;317:620–622. doi: 10.1126/science.1143777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buza-Vidas N, Luc S, Jacobsen SE. Delineation of the earliest lineage commitment steps of haematopoietic stem cells: new developments, controversies and major challenges. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:315–321. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3281de72bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adolfsson J, Mansson R, Buza-Vidas N, Hultquist A, Liuba K, Jensen CT, Bryder D, Yang L, Borge OJ, Thoren LA, et al. Identification of Flt3+ lympho-myeloid stem cells lacking erythro-megakaryocytic potential: a revised road map for adult blood lineage commitment. Cell. 2005;121:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arinobu Y, Mizuno S, Chong Y, Shigematsu H, Iino T, Iwasaki H, Graf T, Mayfield R, Chan S, Kastner P, et al. Reciprocal activation of GATA-1 and PU.1 marks initial specification of hematopoietic stem cells into myeloerythroid and myelolymphoid lineages. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welner RS, Pelayo R, Kincade PW. Evolving views on the genealogy of B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:95–106. doi: 10.1038/nri2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9*.Mansson R, Hultquist A, Luc S, Yang L, Anderson K, Kharazi S, Al-Hashmi S, Liuba K, Thoren L, Adolfsson J, et al. Molecular evidence for hierarchical transcriptional lineage priming in fetal and adult stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Immunity. 2007;26:407–419. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.013. Evidence is presented that differentiation from HSCs to MPPs and then LMPPs in the fetal liver and adult bone marrow involves the progressive down-regulation of Mk/E-specific genes and priming of lymphoid-genes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichogiannopoulou A, Trevisan M, Neben S, Friedrich C, Georgopoulos K. Defects in hemopoietic stem cell activity in Ikaros mutant mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1201–1214. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng H, Yucel R, Kosan C, Klein-Hitpass L, Moroy T. Transcription factor Gfi1 regulates self-renewal and engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 2004;23:4116–4125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hock H, Hamblen MJ, Rooke HM, Schindler JW, Saleque S, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. Gfi-1 restricts proliferation and preserves functional integrity of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431:1002–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature02994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13**.Dias S, Gurbuxani S, Mansson R, Sigvardsson M, Kee BL. E2A proteins promote development of lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors. Immunity. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.015. in press. E2A−/− HSCs are shown to have a defect in generation of LMPPs and initiation of lymphoid-priming in HSCs and LMPPs. However, E2A is dispensable for restriction of Mk/E-lineage potential but the few LMPPs generated in E2A−/− mice have increased G/M differentiation potential. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attema JL, Papathanasiou P, Forsberg EC, Xu J, Smale ST, Weissman IL. Epigenetic characterization of hematopoietic stem cell differentiation using miniChIP and bisulfite sequencing analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12371–12376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704468104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Yoshida T, Hazan I, Zhang J, Ng SY, Naito T, Snippert HJ, Heller EJ, Qi X, Lawton LN, Williams CJ, et al. The role of the chromatin remodeler Mi-2beta in hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and multilineage differentiation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1174–1189. doi: 10.1101/gad.1642808. Conditional deletion of Mi-2beta in hematopoietic cells leads to proliferation and expansion of HSCs followed by exhaustion and loss of mature lymphoid and myeloid progeny. Mi-2beta-deficient HSCs lose expression of stem cell-associated genes and show premature lineage priming consistent with increased differentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian H, Buza-Vidas N, Hyland CD, Jensen CT, Antonchuk J, Mansson R, Thoren LA, Ekblom M, Alexander WS, Jacobsen SE. Critical role of thrombopoietin in maintaining adult quiescent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:671–684. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min IM, Pietramaggiori G, Kim FS, Passegue E, Stevenson KE, Wagers AJ. The transcription factor EGR1 controls both the proliferation and localization of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:380–391. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Dykstra B, Kent D, Bowie M, McCaffrey L, Hamilton M, Lyons K, Lee SJ, Brinkman R, Eaves C. Long-term propagation of distinct hematopoietic differentiation programs in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.015. This large-scale study revealed two major patterns of reconstitution after in vivo transplantation of single LT-HSCs 1) myeloid skewed (alpha) and 2) myeloid/lymphoid balanced (beta). These fates appear to be intrinsically preset. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sitnicka E, Buza-Vidas N, Ahlenius H, Cilio CM, Gekas C, Nygren JM, Mansson R, Cheng M, Jensen CT, Svensson M, et al. Critical role of FLT3 ligand in IL-7 receptor independent T lymphopoiesis and regulation of lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors. Blood. 2007;110:2955–2964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Yoshida T, Ng SY, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Georgopoulos K. Early hematopoietic lineage restrictions directed by Ikaros. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:382–391. doi: 10.1038/ni1314. Ikaros−/− mice lack LSK Flt3high cells but develop G/M-lymphoid restricted progenitors, identifiable by the expression of a GFP reporter under the control of Ikaros regulatory elements. Therefore, Ikaros is dispensable for development of functionally defined LMPPs. However, it was found to be required for further lymphoid differentiation of LMPPs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh H, Medina K, Pongubala JM. Contingent gene regulatory networks and B cell fate specification. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:4949–4953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500480102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nutt SL, Kee BL. The transcriptional regulation of B cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2007;26:715–725. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhandoola A, von Boehmer H, Petrie HT, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Commitment and developmental potential of extrathymic and intrathymic T cell precursors: plenty to choose from. Immunity. 2007;26:678–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Maeda T, Merghoub T, Hobbs RM, Dong L, Maeda M, Zakrzewski J, van den Brink MR, Zelent A, Shigematsu H, Akashi K, et al. Regulation of B versus T lymphoid lineage fate decision by the proto-oncogene LRF. Science. 2007;316:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1140881. This paper demonstrates that LRF actively represses T-cell differentiation in bone marrow progenitors by antagonizing Notch-signaling. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Souabni A, Cobaleda C, Schebesta M, Busslinger M. Pax5 promotes B lymphopoiesis and blocks T cell development by repressing Notch1. Immunity. 2002;17:781–793. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansson R, Zandi S, Andersson K, Martensson IL, Jacobsen SE, Bryder D, Sigvardsson M. B-lineage commitment prior to surface expression of B220 and CD19 on hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-125385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Roessler S, Gyory I, Imhof S, Spivakov M, Williams RR, Busslinger M, Fisher AG, Grosschedl R. Distinct promoters mediate the regulation of Ebf1 gene expression by interleukin-7 and Pax5. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:579–594. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01192-06. This paper provides an elegant molecular dissection of the transcription factors controlling expression of the Ebf1α and Ebf1β promoters. The analysis lends support to a novel model of B-cell lineage specification and commitment involving progressive activation of E2A, EBF and Pax5 combined with feed-back amplification loops that reinforce Ebf1, and consequently Pax5, expression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28**.Cobaleda C, Jochum W, Busslinger M. Conversion of mature B cells into T cells by dedifferentiation to uncommitted progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature06159. Conditional deletion of Pax5 in peripheral mature B cells induces lymphoma and triggers reversion of differentiation, reacquisition of developmental plasticity and T-cell generation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Pongubala JM, Northrup DL, Lancki DW, Medina KL, Treiber T, Bertolino E, Thomas M, Grosschedl R, Allman D, Singh H. Transcription factor EBF restricts alternative lineage options and promotes B cell fate commitment independently of Pax5. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:203–215. doi: 10.1038/ni1555. The authors provide evidence that EBF1 functions in B-cell lineage commitment by suppressing genes such as C/EBPα PU.1 and Id2, and suggest that EBF1 functions independently of Pax5. Indeed, EBF represses the myeloid and T-cell potential of Pax5−/−pro-B-lymphocytes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boos MD, Yokota Y, Eberl G, Kee BL. Mature natural killer cell and lymphoid tissue-inducing cell development requires Id2-mediated suppression of E protein activity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1119–1130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothenberg EV. Negotiation of the T lineage fate decision by transcription-factor interplay and microenvironmental signals. Immunity. 2007;26:690–702. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai AY, Kondo M. Identification of a bone marrow precursor of the earliest thymocytes in adult mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6311–6316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609608104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarz BA, Sambandam A, Maillard I, Harman BC, Love PE, Bhandoola A. Selective thymus settling regulated by cytokine and chemokine receptors. J Immunol. 2007;178:2008–2017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarz BA, Bhandoola A. Circulating hematopoietic progenitors with T lineage potential. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:953–960. doi: 10.1038/ni1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35**.Wada H, Masuda K, Satoh R, Kakugawa K, Ikawa T, Katsura Y, Kawamoto H. Adult T-cell progenitors retain myeloid potential. Nature. 2008;452:768–772. doi: 10.1038/nature06839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36**.Bell JJ, Bhandoola A. The earliest thymic progenitors for T cells possess myeloid lineage potential. Nature. 2008;452:764–767. doi: 10.1038/nature06840. This study, along with Ref 35, demonstrates at the clonal level that adult ETPs possess T and myeloid potential but not B-cell potential. These observations lend support to the hypothesis that ETPs are the progeny of LMPPs or earlier progenitors rather than CLPs, which have already extinguished the myeloid differentiation option. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun XH. Multitasking of helix-loop-helix proteins in lymphopoiesis. Adv Immunol. 2004;84:43–77. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)84002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*.Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Goldrath AW, Murre C. E proteins and Notch signaling cooperate to promote T cell lineage specification and commitment. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1329–1342. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060268. This paper demonstrates that E47 and Notch act in concert to promote T-cell lineage specification and commitment. E47 can induce Notch-target genes, including Hes1, in E2A−/− fetal thymocytes while enforced expression of intracellular Notch can rescue E2A−/−fetal T cell development in vitro. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang D, Claus CL, Vaccarelli G, Braunstein M, Schmitt TM, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Rothenberg EV, Anderson MK. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor HEBAlt is expressed in pro-T cells and enhances the generation of T cell precursors. J Immunol. 2006;177:109–119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taghon TN, David ES, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Rothenberg EV. Delayed, asynchronous, and reversible T-lineage specification induced by Notch/Delta signaling. Genes Dev. 2005;19:965–978. doi: 10.1101/gad.1298305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tydell CC, David-Fung ES, Moore JE, Rowen L, Taghon T, Rothenberg EV. Molecular dissection of prethymic progenitor entry into the T lymphocyte developmental pathway. J Immunol. 2007;179:421–438. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo Y, Maillard I, Chakraborti S, Rothenberg EV, Speck NA. Core binding factors are necessary for natural killer cell development, and cooperate with Notch signaling during T cell specification. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson MK, Hernandez-Hoyos G, Dionne CJ, Arias AM, Chen D, Rothenberg EV. Definition of regulatory network elements for T cell development by perturbation analysis with PU.1 and GATA-3. Dev Biol. 2002;246:103–121. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Franco CB, Scripture-Adams DD, Proekt I, Taghon T, Weiss AH, Yui MA, Adams SL, Diamond RA, Rothenberg EV. Notch/Delta signaling constrains reengineering of pro-T cells by PU.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11993–11998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601188103. PU.1 can divert the fate of specified pro-T cells into myeloid lineages in the absence of Notch signaling, but the presence of Notch ligands prevents such transcriptional programs from emerging thus suppressing alternative lineage fates and ensuring commitment to the T cell lineage. PU.1 may divert cells in the absence of Notch signaling by inducing expression of the E2A antagonist Id2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45**.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Xie H, de Andres-Aguayo L, Graf T. Reprogramming of committed T cell progenitors to macrophages and dendritic cells by C/EBP alpha and PU.1 transcription factors. Immunity. 2006;25:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.011. Enforced expression of C/EBP alpha and PU.1 can induce pre-T cells to transdifferentiate into cells resembling inflammatory macrophage and myeloid dendritic-like cells that contain TCR rearrangements. Evidence is presented that this reprogramming can be counteracted by activated Notch or Gata3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46**.Taghon T, Yui MA, Rothenberg EV. Mast cell lineage diversion of T lineage precursors by the essential T cell transcription factor GATA-3. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:845–855. doi: 10.1038/ni1486. Overexpression of Gata3 inhibits normal T cell differentiation and cell growth but permits fetal thymocytes at the DN1 and DN2 stage to differentiate into mast cells in the absence of Notch signaling. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]