Abstract

Purpose

To identify distinct smoking trajectories during adolescence and assess how smoking-related factors relate to trajectory membership.

Methods

The sample includes 3637 youth from across the state of Minnesota. Measures include tobacco use, smoking behaviors of parents and friends, youth smoking-related attitudes and beliefs, and home smoking policies. A cohort-sequential design was used to identify smoking trajectories, including five cohorts of youth (ages 12–16) followed for 3 years.

Results

Six distinct trajectories of tobacco use were found: nonsmokers (54%), triers (17%), occasional users (10%), early established (7%), late established (8%), and decliners (4%). Several factors were associated with increased likelihood of being in a smoking trajectory group (vs. the nonsmoking group): parental smoking, friend smoking, greater perceptions of the number of adults and teenagers who smoke, and higher functional meaning of tobacco use. In contrast, higher perceived difficulty smoking in public places, negative perceptions of the tobacco industry, and home smoking policies were associated with less likelihood of being in one of the smoking trajectories (vs. the nonsmoking trajectory).

Conclusions

Adolescents exhibit diverse patterns of smoking during adolescence and tobacco-related influences were strong predictors of trajectory membership.

Keywords: Adolescent smoking, Smoking trajectories, Social influences, Smoking attitudes

Cigarette smoking is the most preventable cause of death in the United States [1]. Despite declines in cigarette smoking in the late 1990s, rates of smoking among youth remain high, with 23% of 12th graders reporting smoking in the past 30 days [2]. Cigarette smoking among youth is of particular concern because patterns of smoking are often established during adolescence [3].

Research suggests that individuals progress through a series of stages before becoming a regular smoker, including smoking preparation or susceptibility, trying cigarettes, repeated experimentation, regular use, and dependence [4–6]. Although it is common for youth to progress through the smoking stages during adolescence, results from numerous studies suggest that adolescents follow different patterns of smoking [7–10].

Researchers have identified several distinct patterns of smoking during adolescence including nonsmoking or experimental use, occasional use, increasing use, and regular/daily smoking [7–10]. There are several methodological limitations, however, of current studies in this area. First, studies often include school-based samples, which do not include school dropouts or youth in alternative education programs [7,11–13]. Second, studies often include a portion of adolescence (e.g., high school years), rather than the entire spectrum [7,11,14]. Third, sample sizes of numerous studies are relatively small, potentially limiting the ability to characterize less common trajectories [10,12]. Finally, intervals between surveys have varied from annual assessments to lengthier intervals [13–15], which limit the detail with which the progression of smoking during adolescence can be described. The present study addresses these limitations by examining smoking trajectories from age 12 to 19 among 3637 youth enrolled in a population-based cohort study who were interviewed every 6 months about their smoking behavior.

Several studies have also sought to examine psychosocial correlates of trajectory membership [7,8,10,12,13,15,16]. These studies, however, have not considered the range of smoking-related factors that have been shown to play a key role in the development of smoking. Most studies have included peer and parent smoking and an overall measure of smoking attitudes [7,10,11,13], but few have examined how other smoking-related factors are associated with smoking patterns, such as perceptions of the number of adults and teenagers who smoke, functional meaning of tobacco use, perceived difficulty smoking in public places, negative perceptions of the tobacco industry, and home smoking policies. Examining how these factors are associated with trajectory membership is particularly important because they are often targeted through smoking prevention programs.

The main goals of the present study are to (1) identify distinct developmental trajectories of tobacco use from age 12 to 19, and (2) examine how various smoking-related factors are associated with trajectory group membership. We hypothesize that several distinct patterns of smoking progression will emerge including a nonsmoking or experimental use group, an occasional use group, an increasing group, and regular/daily smoking group. We also hypothesize that smoking-related factors not previously examined (e.g., perceptions that more adults and teenagers smoke, and higher functional meaning of tobacco use) will be associated with smoking trajectory membership (vs. being a nonsmoker). In contrast, we hypothesize that higher perceived difficulty smoking in public places, negative perceptions of the tobacco industry, and home smoking policies will be associated with membership in the nonsmoking trajectory (vs. the smoking trajectories).

Methods

MACC design

This study utilizes data from the Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort (MACC) Study. The MACC study is a prospective cohort study, with 3637 individuals representing a stratified random sample of youth across the state of Minnesota. Youth were aged 12 to 16 years of age at baseline, and were interviewed every 6 months for 3 years. The University of Minnesota institutional review board approved this study.

Adolescent participants

A combination of probability and quota sampling methods (to assure equal age distribution) was used to recruit participants. Recruitment was conducted by telephone by Clearwater Research, Inc., using modified random digit dial sampling. Households were called to identify those with at least one teenager between the ages of 12 and 16, and within eligible households, respondents were selected at random from among age quota cells that were still open.

The baseline interview included 3637 youth across the state of Minnesota (58.5% response rate). Approximately equal numbers of male (49%) and female (51%) adolescents participated, and participants were primarily white (84%), with 4% black, and ≤2% of each of the other ethnic groups including American Indian, Asian, Hispanic and multiracial. A high response rate was maintained, with an average of 93.1% of the original sample participating in each of the first six rounds of data collection (range: 89.5%–96.7%).

Parental permission was obtained to conduct each interview if the respondent was less than 18 years old. Each interview lasted 10 to 20 minutes, depending on the smoking status of the respondent, and the interview was structured so that spoken responses would not be revealing to anyone overhearing the respondent. Study participants under the age of 18 received $10 for each completed interview, and participants 18 and older received $15.

Measures

Tobacco use

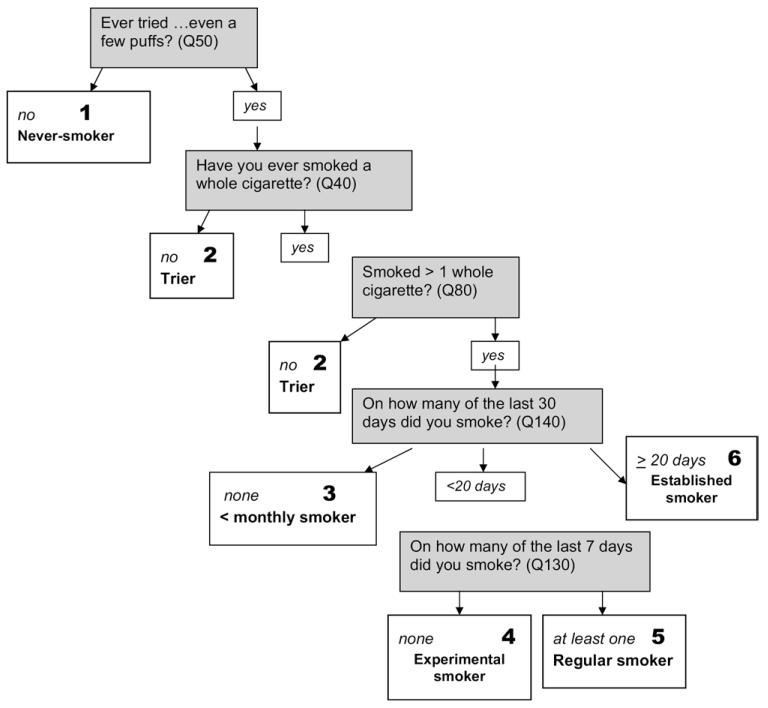

Responses to a series of questions were used to create a six-point index of tobacco use (1 = never smoker, 2 = tier, 3 = less than a monthly smoker, 4 = experimental smoker, 5 = regular smoker, 6 = established smoker) (see Figure 1). A “never smoker” was defined as someone who never smoked (not even a puff) in their lifetime. A “trier” was defined as someone who smoked one cigarette or less in their lifetime. A “less than monthly smoker” was defined as someone who smoked more than one cigarette in their lifetime, but did not smoke in the past 30 days. An “experimenter” was defined as someone who smoked at least once in the past 30 days. A “regular smoker” was defined as someone who smoked at least once in the past week. Finally, an “established smoker” was defined as someone who smoked daily or most days. All smoking stage categories are mutually exclusive.

Figure 1.

Stage model of smoking acquisition.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic information, including sex, race/ethnicity, and family composition was collected from youth during the first interview. Family composition was coded as a dichotomous variable in which “1” denotes living with two parents (biological or step parents) and “0” denotes other living arrangements. Community type (e.g., rural and urban) was coded based on geopolitical unit membership.

Other smoking-related factors measured in the present study are described below.

Social influences

Participants indicated if their mother/stepmother and father/stepfather smoke cigarettes (yes/no). Participants also indicated the number of their four best friends that smoke cigarettes (0–4).

Attitudes and beliefs

Four types of attitudes/beliefs were assessed.

Number of adults and teens who smoke: participants indicated the number of adults and teenagers their age they think smoke. Response options ranged from “0” (none) to “4” (almost all of them).

Difficulty smoking in public places: participants indicated how difficult it is for someone under the age of 18 to smoke in 10 public places including: (1) school property, (2) restaurants, (3) shopping mall, (4) pool hall, arcade, or bowling alley, (5) parks or playgrounds, (6) own home, (7) best friend’s home, (8) coffee house, (9) teen dance club, and (10) a place to smoke during school hours. Response options ranged from “0” (not at all hard) to “4” (very hard). The mean of the 10 items were used for analysis.

Perceptions of tobacco industry: participants indicated their perceptions of the tobacco industry using a five-point Likert scale (0 = strongly agree, 4 = strongly disagree). The three items include “cigarette companies are trying to get young people to smoke,” “cigarette companies get too much blame for young people smoking,” and “cigarette companies are making too much money off of young people.” Items were recoded so a higher value represents more negative perceptions of the tobacco industry.

Functional meaning of tobacco use: functional meaning of tobacco included four items using a five-point Likert scale (0 = strongly agree, 4 = strongly disagree). The four items include: “cigarettes are good for when a person is bored,” “cigarettes can help people control their weight,” “when someone’s angry or nervous, a cigarette can calm them down,” and “when a person is feeling down, a cigarette can really help them feel better.”

Home smoking policies

Participants indicated whether adults who live with them are allowed to smoke inside the home (yes/no), and if adult guests are allowed to smoke in the home (yes/no).

The range, mean, and standard deviation for all study variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all study variables

| Variable | Range | Mean or % | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics Community type |

|||

| % Urban | — | 13.50 | — |

| % Suburban | — | 35.19 | — |

| % Rural/small city | — | 51.31 | — |

| % White | — | 85.15 | — |

| % Female | — | 50.78 | — |

| % Two parent family | — | 81.41 | — |

| Social influences | |||

| # of four closest friends who smoke | 0–4 | .79 | 1.21 |

| % Parent smoking | — | 34.10 | — |

| Smoking-related attitudes/beliefs | |||

| # Teens who smoke | 0–4 | 1.96 | .93 |

| # Adults who smoke | 0–4 | 2.29 | .72 |

| Difficulty smoking in public places | 0–4 | 2.36 | .63 |

| Perceptions of tobacco industry | 0–4 | 3.03 | .77 |

| Functional meaning of tobacco use | 0–4 | 1.02 | .85 |

| Nonsmoking policies | |||

| % Resident adults | — | 69.91 | — |

| % for adult visitors | — | 65.99 | — |

Data analytic strategy

Identification of smoking trajectories

A cohort-sequential design was used to identify patterns of smoking from age 12 to 19, following five cohorts (ages 12 to 16) for 3 years. Semiparametric, group-based methods developed by Nagin et al. [17,18] (SAS PROC TRAJ) were used to identify groups of individuals that follow similar developmental patterns of smoking during adolescence. All available data were used from participants, except those who were missing data for three or more of the six data collection points. A censored normal model was estimated because a psychometric scale was used to measure smoking at each time point. Procedures described by Nagin [18] were used to select the model that best fit the data. Specifically, models with progressively more groups were computed. The best-fitting model was chosen based on the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), convergence, and a BIC-based calculation assessing the probability that the model chosen is the correct model. The BIC is the most widely used criteria for model selection, with a BIC closer to 0 indicating better model fit. All models were initially estimated with cubic as the highest level polynomial. After the number of groups was determined, the trajectories were refined to reflect the optimal polynomial order.

After identifying the optimal number of trajectory groups, a generalized logit model was used to assess the relationship between age at baseline and trajectory group membership. Age at baseline was the independent variable (five categories: 12–16) and trajectory group membership was the dependent variable in the model. Finally, multivariate logit models were used to assess the association between demographic and tobacco-related factors at baseline and trajectory group membership. The nonuser trajectory group served as the reference category for all analyses.

Results

Tobacco use trajectories

First, we identified groups of individuals that follow a similar pattern of tobacco use from age 12 to 19. Models were estimated with two to six groups. BICs continued to get closer to 0 as the number of groups increased (BIC2 = -29031.51; BIC3 = -25361.48; BIC4 = -23946.58, BIC5 = -23279.86). The BIC for the six-group model (BIC = -22394.28) was closest to 0, suggesting the six-group model fit these data best. A seven-group model was estimated but failed to reach convergence. The posterior probabilities for the six-group model also suggested a good fit, with probabilities ranging from 90% to 97%. Higher probabilities (>70%) suggest that the data show distinct patterns of smoking.

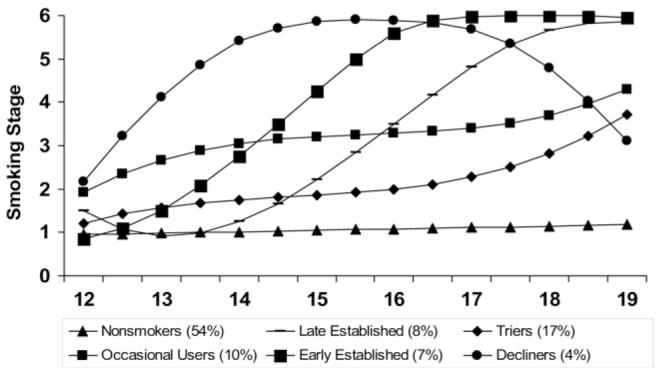

The six trajectory groups are shown in Figure 2. The figure shows the smoking stages by age for the six groups. The largest group identified, called the “nonsmokers,” consists of 54% of the youth in this sample and shows no tobacco use from age 12 to 19. The next two trajectory groups included youth who used tobacco infrequently during adolescence. These groups are called the “triers” and the “occasional users,” and comprise of 17% and 10% of the sample, respectively. Both of these groups show slight increases in their tobacco use during adolescence, and by age 19 report smoking less than once a month. Although both groups smoke infrequently, the “occasional users” show consistently more tobacco use than the “triers” during this time period. The final three trajectory groups include youth who became regular smokers at some point from age 12 to 19. The fourth group, called the “early established” group (7% of the sample), shows steady increases in tobacco use until age 16 when they became regular smokers. The fifth group is the “late established” group, and is comprised of 8% of the sample. This group is characterized by a gradual progression of smoking from age 14 to 18, when they became regular smokers. The final group, called the “decliner” group, is comprised of 4% of the sample. These youth became regular smokers by the age of 14 and begin to show declines in smoking around age 17.

Figure 2.

Smoking stages by age for the six empirically derived smoking trajectory groups.

Predictors of trajectory membership

First, we examined the association between age and trajectory membership because youth in this study ranged from age 12 to 16 at baseline. We found a statistically significant relationship between age at baseline and trajectory group (χ2 = 208.16, p < .0001), so age was included as a covariate in all subsequent analyses.

Next, we examined the association between demographic characteristics and trajectory group membership, with the nonuser group serving as the reference category (Table 2). Community type, race, and family structure were significantly associated with trajectory group membership, after adjusting for age at baseline. Urban youth were more likely to be triers, compared to youth living in rural areas and small cities. In contrast, youth living in suburban areas were less likely to develop all the smoking trajectory groups than youth living in rural areas and small cities, although only the occasional user and late onset trajectory groups reached statistical significance. A similar trend was found for race. White youth were less likely than youth of other races to belong to all five smoking trajectory groups, with the odds ratio reaching statistical significance for the trier, late onset, and decliner groups. Youth living with two parents, were less likely to belong to all five smoking trajectory groups, compared to youth who did not live with two parents. Gender was not a significant predictor of trajectory group membership.

Table 2.

Tobacco use trajectory groups by baseline variablesa

| Characteristic | Nonusers (54%) versus |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (CI) | ||||||

| Triers (18%) | Occasional users (9%) | Early onset (7%) | Late onset (8%) | Decliners (4%) | Chi-square | |

| Community typeb | 41.94* | |||||

| Urban | 1.60 (1.24, 2.08) | 1.01 (.71, 1.43) | 1.02 (.69, 1.52) | .88 (.58, 1.31) | 1.40 (.86, 2.28) | |

| Suburban | .83 (.68, 1.02) | .67 (.51, .86) | .76 (.57, 1.00) | .65 (.49, .86) | .67 (.45, 1.00) | |

| Racec | 31.79* | |||||

| White | .60 (.47, .76) | .75 (.54, 1.05) | .87 (.59, 1.26) | .64 (.45, .90) | .41 (.27, .61) | |

| Genderd | 10.51 | |||||

| Female | .89 (.74, 1.07) | 1.01 (.81, 1.28) | 1.00 (.78, 1.30) | 1.20 (.93, 1.55) | 1.55 (1.08, 2.22) | |

| Family structuree | 73.57* | |||||

| Two parent | .64 (.50, .81) | .62 (.46, .82) | .42 (.31, .56) | .57 (.41, .77) | .28 (.19, .41) | |

OR = odds ratio; CI confidence interval; Models adjusted for cohort.

Generalized logit model using nonsmokers as reference category.

Reference category = rural/small city.

Reference category = other race.

Reference category = male.

Non two-parent household

p .05.

Next, we examined the association between smoking-related influences and trajectory group membership (Table 3). All models included age at baseline, community type, race, and family structure as covariates. Having a parent who smoked increased the likelihood of being in each of the five smoking trajectories (vs. the nonsmoking trajectory). Similarly, having more friends who smoke was positively associated with membership in each of the five smoking trajectory groups (vs. nonsmokers). Perceptions that a higher number of adults and teenagers their age smoke were also positively associated with membership in all five smoking trajectory groups. In contrast, higher perceived difficul-ties of finding public places to smoke was negatively associated with membership in all smoking trajectories (vs. nonsmokers). Negative perceptions of the tobacco industry were negatively associated with membership in four of the five smoking trajectory groups. Higher functional meaning of tobacco use was positively associated with four of the five trajectory groups. Finally, having home smoking policies related to resident adults and visitors were negatively associated with membership in all smoking trajectory groups (compared to nonsmokers).

Table 3.

Tobacco use trajectory groups by baseline variablesa

| Characteristic | Nonusers (54%) versus |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (CI) | ||||||

| Triers (18%) | Occasional users (9%) | Early onset (7%) | Late onset (8%) | Decliners (4%) | χ2 | |

| Social influences | ||||||

| Parent smoking | 2.40 (1.93, 2.98) | 3.06 (2.34, 4.01) | 4.37 (3.20, 5.97) | 2.22 (1.64, 3.01) | 8.39 (5.09, 13.81) | 199.14* |

| # Friends who smk | 1.68 (1.51, 1.86) | 2.66 (2.38, 2.98) | 3.46 (3.06, 3.92) | 2.13 (1.88, 2.41) | 5.91 (4.96, 7.05) | 604.02* |

| Attitudes/beliefs | ||||||

| # Teens who smk | 1.32 (1.18, 1.48) | 1.93 (1.68, 2.22) | 2.11 (1.81, 2.47) | 1.58 (1.35, 1.85) | 3.01 (2.43, 3.72) | 211.88* |

| # Adults who smk | 1.36 (1.19, 1.55) | 1.70 (1.44, 2.00) | 1.95 (1.62, 2.34) | 1.33 (1.11, 1.60) | 2.02 (1.58, 2.59) | 96.24* |

| Smoking difficulty | 0.80 (0.68, 0.94) | 0.72 (0.59, 0.88) | 0.54 (0.43, 0.68) | 0.71 (0.56, 0.89) | 0.28 (0.21, 0.38) | 84.04* |

| Tobacco industry | 0.92 (0.82, 1.04) | 0.80 (0.69, 0.92) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.78) | 0.82 (0.70, 0.96) | 0.53 (0.43, 0.65) | 57.02* |

| Functional meaning | 1.07 (0.95, 1.20) | 1.53 (1.33, 1.75) | 2.08 (1.79, 2.41) | 1.44 (1.23, 1.67) | 2.67 (2.19, 3.24) | 182.01* |

| Nonsmoking policies | ||||||

| Resident adults | .51 (.41, .62) | .40 (.32, .52) | .33 (.25, .43) | .52 (.39, .69) | .20 (.14, .29) | 153.16* |

| Adults visitors | .51 (.42, .63) | .43 (.34, .55) | .30 (.23, .39) | .51 (.39, .66) | .21 (.15, .31) | 159.26* |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; Smk = smoke; all models adjusted for cohort, region, race, and family structure.

Generalized logit model using nonsmokers as reference category

p .05.

Discussion

Analyses revealed six distinct trajectory groups that exhibited diverse patterns of smoking during adolescence: nonsmokers, triers, occasional users, early established, late established, and decliners. The trajectory groups identified in this population-based cohort are similar to those found in previous school-based studies. Soldz and Cui [13], for example, found six similar trajectories of smoking among a school-based sample of 6th through 12th graders. Inconsistent with our hypotheses and several previous studies [9], we did not find a group of smokers who were consistently regular smokers throughout adolescence. This may be because our trajectories started at a relatively young age, perhaps before many youth have established regular smoking patterns.

One of the more interesting groups we found was the decliner group. The decliner group had the earliest smoking onset and most rapid escalation of any smoking trajectory and this group was the only group where there was a decline in smoking during adolescence. Some studies indicate that light and moderate smokers often move into heavier patterns of consumption as they move into young adulthood, and our study shows that some smokers smoke less as they progress through adolescence. This is not to say, however, that early and rapid escalation increases the chances that a young smoker will be able to quit. Understanding differences between youth who continue to smoke versus those that decline in use at the end of high school could provide important information for prevention efforts.

A more precise approach than in previous studies was used to characterize smoking during adolescence, as participants in the current study were interviewed every 6 months (vs. annual or less frequent observations). Specifically, the shorter time intervals allowed greater precision in determining when significant changes in smoking occur. Our six trajectories clearly show that smoking is continually changing during adolescence. For example, in early adolescence, the majority of smoking trajectories show increases in smoking every 6 months between the ages of 12 and 14. Furthermore, the trajectories show that the majority of youth who smoke during adolescence begin experimenting by age 12 (or shortly thereafter), suggesting the importance of the early intervention (before age 12).

The trajectories found in this study also highlight important changes that occur in smoking during mid and late adolescence. Unlike the other groups, the late established smokers did not begin smoking until age 14, and both the early and late established groups continued to increase tobacco consumption until late adolescence when they become regular smokers. In contrast, the decliners began reducing smoking by age 17. These patterns suggest the need to focus prevention and interventions throughout adolescence. Furthermore, although much effort focuses on preventing initiation, these results suggest that interventions that focus on acceleration are also needed during mid- and late-adolescence.

A major contribution of the present study is the examination of how a variety of smoking-related factors are associated with trajectory membership through adolescence. All of the smoking trajectories differ significantly from the nonuser trajectory on all factors with the exception of the Trier group. Triers were no different from nonsmokers in their attitudes toward the tobacco industry and their reported functional meaning of smoking. However, Triers were more likely than nonusers to have a friend and/or parent who smokes and to live in a home where smoking is allowed indoors. Perhaps the Triers’ beliefs and attitudes offered some protection against moving into a heavier smoking pattern despite an environment that would seem to be conducive to an earlier smoking onset and a more rapidly intensifying smoking pattern.

This study has limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, the majority of participants were white, and results may not generalize to youth of other racial and ethnic backgrounds. Second, over one-third of potential participants declined to participate in this study. Although the present response rate is consistent with other current random digit dial studies [19], nonparticipants may differ from those who did participate in the study. No information was gathered on nonparticipants so we are unable to test for nonresponse bias. Finally, associations between trajectory group membership and tobacco use were examined at baseline when youth were between 12 and 16 years of age. Because predictors examined in this study are likely to change over time, additional studies are needed to examine the relationship between time varying predictors and trajectory membership.

This study addresses several limitations of prior research, and shows that adolescents exhibit diverse patterns of smoking and that smoking is continually changing during adolescence. The findings reinforce the importance of early intervention (prior to age 12) and continual prevention and intervention efforts through mid- and late-adolescence. Tobacco-related influences were strong predictors of trajectory membership, indicating their importance in long-term patterns of use, not just initiation. Future studies need to focus on how smoking-related interventions may alter smoking trajectories.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institute of Health R01-CA086191, Jean Forster, Principal Investigator.

References

- [1].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2000

- [2].Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the Future National Results on Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2005. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: [Google Scholar]

- [3].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Preventing Tobacco Use among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Flay BR, Hu FB, Richardson J. Psychosocial predictors of different stages of cigarette smoking among high school students. Prev Med. 1998;27(5 Pt 3):A9–18. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mayhew KP, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59(Suppl 1):S61–81. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, et al. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15(5):355–61. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Abroms L, Simons-Morton B, Haynie DL, et al. Psychosocial predictors of smoking trajectories during middle and high school. Addiction. 2005;100(6):852–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Juon HS, Ensminger ME, Sydnor KD. A longitudinal study of developmental trajectories to young adult cigarette smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66(3):303–14. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, et al. Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking and their correlates from early adolescence to young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(3):400–10. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].White HR, Pandina RJ, Chen PH. Developmental trajectories of cigarette use from early adolescence into young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;65(2):167–78. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, et al. Identifying and characterizing adolescent smoking trajectories. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2023–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Karp I, O’Loughlin J, Paradis G, et al. Smoking trajectories of adolescent novice smokers in a longitudinal study of tobacco use. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(6):445–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Soldz S, Cui X. Pathways through adolescent smoking: a 7-year longitudinal grouping analysis. Health Psychol. 2002;21(5):495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Colder CR, Mehta P, Balanda K, et al. Identifying trajectories of adolescent smoking: an application of latent growth mixture modeling. Health Psychol. 2001;20(2):127–35. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stanton WR, Flay BR, Colder CR, et al. Identifying and predicting adolescent smokers’ developmental trajectories. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(5):843–52. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001734076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, et al. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychol. 2000;19(3):223–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semi-parametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:139–77. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nagin DS. Group-Based Modeling of Development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Biener L, Garrett CA, Gilpin EA, et al. Consequences of declining survey response rates for smoking prevalence estimates. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):254–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]