Abstract

A depth-of-processing incidental recall task for maternal referent stimuli was utilized to assess basic memory processes and the affective valence of maternal-representations among abused (N = 63), neglected (N= 33) and nonmaltreated (N = 128) school-aged children. Self-reported and observer-rated indices of internalizing symptoms were also assessed. Abused children demonstrated impairments in recall compared to neglected and nonmaltreated children. Although abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated children did not differ in valence of maternal representations, positive- and negative-maternal schemas related to internalizing symptoms differently among subgroups of maltreated children. Valence of maternal schema was critical in differentiating those with high and low internalizing symptomatology among the neglected children only. Implications for clinical intervention and prevention efforts are underscored.

Introduction

In the current literature, a lack of consensus on how the experience of trauma affects memory, if at all, has motivated continued research regarding the relation between memory and trauma (Howe, Cicchetti, Toth, & Cerrito, 2004; Howe, Toth, & Cicchetti, 2006). Empirical evidence of brain structure alteration in response to prolonged stress (e.g., Bremner, 2002; Bremner & Narayan, 1998; DeBellis et al., 1999; Sapolsky, 1992) and impaired memory performance among adults who were traumatized as children (e.g., Henderson, Hargreaves, Gregory, & Williams, 2002) suggest that trauma may have an adverse effect on memory. In contrast, evidence also supports the contention that traumatic experiences may actually enhance memory for the trauma (e.g., Howe, Courage, & Peterson, 1994, 1995). One possible explanation for these inconsistencies is that the experience of trauma per se may not be sufficient to explain memory processes among maltreated children. Therefore, others have suggested that the impact of stress upon memory should be assessed in relation to other sequelae of maltreatment that may be related to memory such as quality of attachment organization and psychopathology (e.g., Alexander, Quas, & Goodman, 2002; Goodman, 2005; Greenhoot, McCloskey, & Glisky, 2005).

In this article, we first review what is known about trauma and memory. We then discuss representational models as a framework for processing interpersonal information and as an organizing schema for memory. Next, we review the impact of maltreatment upon the development of representational models, with a focus on maternal- representations. Finally, we examine the relation of affective representations of primary caregivers to depressive symptoms. In light of the literature reviewed we detail the specific aims of this investigation, which are: (1) to address significant gaps in the literature with respect to emotionally valenced semantic memory recall among maltreated children and (2) to assess the relation of maltreatment and the valence of maternal schema to internalizing symptomatology.

Memory and Trauma

Over the past several decades, research has burgeoned in attempts to clarify the association between trauma and memory. Initial investigations assessed memory for trauma by evaluating nonmaltreated children's memory for analog traumas such as unanticipated emergency room procedures (Howe et al., 1994, 1995) or hospital experiences that involve genital touching (e.g., Goodman & Quas, 1997). Such research coheres to support the notion that increased levels of stress lead to better memory for the event itself (for review see Howe, 1998, 2000). Nonetheless, it is unlikely that intensity of the emotions invoked by analog traumas is equivalent to that which accompanies the experience of physical or sexual abuse, or the experience of chronic neglect. Therefore, further research is needed among populations of traumatized children.

Unfortunately, there is a much smaller body of literature that exists on how maltreatment affects memory, particularly among children (Eisen, Qin, Goodman & Davis, 2002). Only recently have researchers began to conduct longitudinal and prospective research designs to examine maltreated children's memory (Alexander, Quas, Goodman, Ghetti, Edelstein, Redlich, et al., 2005; Eisen, Goodman, Qin, & Davis, 2005; Greenhoot et al., 2005). Overall, findings from these investigations have not supported deficiencies in memory performance for maltreated children. In fact, this recent longitudinal research with maltreated children suggests that memories of trauma are durable, even when reporting on traumas that occurred 12-21 years prior (Alexander et al., 2005).

Despite the lack of an association between maltreatment and memory impairments in the literature reviewed thus far, it should be noted that this research has focused on autobiographical memory for traumatic events. However, there are reasons to suspect that maltreatment might have a more generalized impact on basic memory function. For example, child maltreatment may impact memory function because of physiological changes to brain regions related to memory processes (e.g., Bremner, Krystal, Southwick & Charney, 1995). Moreover, differences among maltreated children in cognitive control strategies and attentional focus or in attachment and internal working models may lead to differences in the initial encoding of information (Alexander et al, 2002; Rieder & Cicchetti, 1989).

Therefore, research on basic memory processes (i.e., encoding, storage, and retrieval of neutral, nontraumatic stimuli) among maltreated children is critical for the advancement of our understanding of how trauma affects memory. In a seminal investigation, Howe and colleagues (2004) addressed basic memory through the assessment of true and false recall for neutral stimuli among maltreated and nonmaltreated children, revealing no differences in memory functioning as a result of maltreatment. Similarly, a recent examination of neurobehavioral sequelae of child sexual abuse found no significant differences in memory function between abused and nonabused children (Porter, Lawson & Bigler, 2005), despite elevations in psychopathology and diminished performance on tests of attention and executive function for the abused group. Therefore, the extant research does not support alterations in basic memory functioning among maltreated children.

Nonetheless, it is essential to increase our knowledge of these basic processes, especially with regard to memory that is affectively valenced and attachment-related. From an attachment theory perspective, children who are regularly rejected by their caregivers when seeking support may develop cognitive strategies that reduce their attention and memory for attachment related stimuli, thus minimizing their likelihood of experiencing subsequent rejection (Main, 1990). Therefore, there is reason to believe that although maltreated children's memory for neutral stimuli may be comparable to nonmaltreated children (Valentino, Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, in press), when the to-be-remembered stimuli are attachment-related, maltreated children may exhibit impairments relative to nonmaltreated children.

Among normative samples of children, there is evidence for differences between memory performances for attachment-related and nonattachment-related experiences (Alexander et al., 2002; Alexander & Edelstein, 2001). Specifically, children's memory performance seems to be associated with attachment security for attachment-related experiences only, whereas memory performance is unrelated to attachment security for nonattachment- related events (Alexander & Edelstein, 2001). Although the extant body of literature on the relationship between children's memory and quality of attachment orientation, assessed through the Strange Situation paradigm, has been limited to normative samples of preschool-aged children, the findings have been consistent in demonstrating that children's attachment has important implications for their memory (Alexander & Edelstein, 2001; Belsky, Spritz & Crnic, 1996; Kirsh & Cassidy, 1997). For example, the work of Belsky and colleagues (1996) suggests that children remember information best when it is consistent with their attachment schema or internal working models. Additionally, insecure attachment has been related to alterations in memory performance in both children and adults (Alexander et al., 2002; Goodman, 2005, for review). In the present investigation, we extend the examination of memory for attachment-related stimuli to school-aged maltreated children. Utilizing a depth-of-processing incidental recall memory task, this study is able to assess recall performance while simultaneously gaining an implicit measure of the affective valence of school-aged children's maternal schema.

Relational Schema/ Representational Models

Several different developmental theories cohere to suggest that relational schemas, or representational models, are formed as a result of children's early interactions with their primary caregivers. Depending on the theoretical perspective, the internalizations of these early interaction experiences are labeled as representational models, or internal working models (IWMs) within attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969; Bretherton & Munholland, 1999) and as schemas or scripts within social cognitive theory (Baldwin, 1992).

Despite differences in terminology for these constructs, both attachment and social-cognitive theorists agree that specific relationship experiences are encoded as cognitive representations of the self, other, and the self in relation to other, which are used to guide perception, attention, future expectations, and behavior within interpersonal contexts (Baldwin, 1992; Main, Kaplan & Cassidy, 1985; Safran, 1990). As such, these cognitive representations serve as important organizing schemas for memory that can be used to facilitate encoding and recall (Markus, 1977; Rogers, 1981). Moreover, relational schemas are critical for the development of self regulation and are salient predictors of behavioral outcomes (Sroufe, 1983, 1989). Therefore, the representational models that emerge from early interactions between child and caregiver have a long-lasting impact on children's developmental trajectories. Unfortunately, early parent-child relationships within maltreating families are often characterized by negative interactions and have an adverse effect on children's representational models (see Azar, 2002 for review).

Child Maltreatment, Representational Models and Internalizing Symptomatology

Maltreating families fail to provide many of the average expectable experiences that promote the development of adaptive functioning (Cerezo, 1997). As such, child maltreatment is associated with the unsuccessful resolution of stage-salient developmental tasks, setting many maltreated children on pathways towards maladaptive developmental outcomes and psychopathology (Cicchetti, 1989; see Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006 for a review). In particular, experiences of poor quality caregiving may lead to the development of negative IWMs (Crittenden & Ainsworth, 1989; Oppenheim, Emde, & Warren, 1997), which hinders children's ability to negotiate developmental challenges (Cicchetti, 1989; Toth, Cicchetti, & Kim, 2002). Empirical work with maltreated preschoolers provides evidence that children who are raised in a maltreating environment are more likely to develop negative representations of caregivers and of themselves than are their nonmaltreated peers (Toth, Cicchetti, Macfie, & Emde, 1997). Furthermore, longitudinal assessment of maltreated preschoolers' story-stem narratives has revealed that negative representations of parents and of the self are stable over time (Toth, Cicchetti, Macfie, Maughan, & VanMeenen, 2000).

Moreover, there is empirical support for the relation of negative maternal representations with increased internalizing symptomatology and emotion dysregulation (Shields, Ryan, & Cicchetti, 2001; Toth & Cicchetti, 1996; Toth et al. 2002). Overall, it seems that internal representations of mother influence the level of disturbance that children exhibit.

Conversely, additional studies have failed to detect a causal relationship between children's report of their perceptions of parental warmth and nurturance and their mental health outcomes (McCloskey, Figueredo & Koss;1995). It is noteworthy, however, that a number of these studies have utilized paradigms that assess children's perceptions of mother through explicit, direct questioning. Therefore, child reports could be subject to response bias, reducing the likelihood that children will admit having negative perceptions of parents. To address this issue, the current investigation employs a paradigm from the literature on basic memory functioning and cognitive performance that allows for the assessment of maternal representation in an implicit manner. In addition, this study advances prior research on the relation among maltreatment, maternal representations and internalizing symptoms by including the examination of maltreatment subtype experiences.

The Present Investigation

Based upon our extant knowledge of trauma, memory, and maternal representations, and in order to address the significant gaps in the literature identified above, this investigation sought to: (1) Determine whether children's recall performance will differ as a function of maltreatment subtype experiences. Because children who are regularly rejected by caregivers may develop cognitive strategies to reduce their attention and memory for attachment-related stimuli to minimize subsequent rejection, we hypothesized that abused and neglected children will demonstrate impairments in memory performance for maternal-referent stimuli in comparison to nonmaltreated children; (2) Examine whether abused, neglected and nonmaltreated children differ in the affective valence of their maternal-schema. Specifically, we expected that abused children would have the most negative maternal- schemas in relation to nonmaltreated children; (3) Evaluate how maltreatment and maternal-schema might be related to depression. We anticipated that the affective valence of maternal schemas would be related to depression differently between those who have been abused, neglected and nonmaltreated. In light of research that has demonstrated that the affective valence of self-schema relates to dissociative symptoms differently among neglected children in comparison to abused and nonmaltreated children (Valentino et al., in press), we expected that the affective valence of maternal schemas would relate to depressive symptoms differently among neglected children in comparison to abused and nonmaltreated children. However, the specific pattern of results was not predicted because of insufficient prior research regarding maltreatment subtype and the relationship between maternal representations and the development of internalizing symptoms.

Method

Subjects

Participants in this study consisted of 96 maltreated children and 128 nonmaltreated children between the ages of 8.0 and 13.5 years (average age = 10.0, SD = 1.46). Children attended a research summer camp program in upstate New York that was designed to provide maltreated and nonmaltreated children from low socioeconomic status families a recreational experience in which children's behavior could be observed in an ecologically valid context (see Cicchetti & Manly, 1990, for a description of the camp context).

The maltreated children who participated in this investigation were recruited from those reported to the local Department of Human Services (DHS) because of concerns related to child maltreatment. All maltreated children were living at home in the care of their biological mothers. Children's maltreatment status was determined through examination of Child Protective Service (CPS) and Preventive Services records at DHS, for which parents provided consent. Maternal interviews, during which research assistants inquired about a history of abusive and/or neglectful acts, were also conducted to investigate families' maltreatment histories. The presence or absence of four subtypes of maltreatment was determined for each child utilizing the Maltreatment Classification System (Barnett, Manly & Cicchetti, 1993). 75 percent of the children had experienced emotional maltreatment, 88% neglect, 52% physical abuse, and 27% sexual abuse. Comorbidity of subtypes of maltreatment is common and has been well documented (Barnett et al., 1993); in the present study subtype comorbidity occurred for 81.2 % of the sample.

A primary subtype classification was then determined for each child based upon a hierarchy that assesses the degree to which a particular experience of maltreatment violates social norms (Manly, Cicchetti & Barnett, 1994). Sexual abuse is conceptualized as the most serious deviation from societal standards; therefore, any children who were sexually abused received this as their primary subtype designation. Children who were physically abused, but not sexually abused, were classified into the physical abuse group; children who were neglected but did not experience sexual or physical abuse were classified in the neglect group. No maltreated children in this investigation exclusively experienced emotional maltreatment; therefore, no children received emotional maltreatment as their primary subtype designation. These primary subtype effects were further conceptualized as acts of commission (e.g., sexual abuse and physical abuse) versus acts of omission (e.g. neglect), based upon the knowledge that these experiences may exert differential impacts upon children's development (Shields & Cicchetti, 2001; Smetana, Toth, Cicchetti, Bruce, Kane & Daddis, 1999; Trickett & McBride-Chang, 1995). Thus, any child who experienced physical or sexual abuse, regardless of concomitant neglect, was classified into the abused group (N = 63). The remaining maltreated children (N = 33) were neglected. The presence of subtype comorbidity between abused and neglected groups was significantly different, with 95.2% of the abused group having experienced at least two subtypes of maltreatment, compared to 54.5% of the neglected group, χ2(1) = 23.54, p < .001; this difference is consistent with the hierarchical criteria used to distinguish between groups.

For demographic comparability to the maltreatment sample, low- SES nonmaltreated families receiving public assistance in the form of Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) were recruited. Informed consent and child assent were obtained for participation in research and parental permission allowed researchers to examine CPS records. Nonmaltreatment status was additionally confirmed by the absence of CPS or Preventive Services records for the family, as well as through a maternal interview to investigate family's maltreatment history.

The families of the abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated groups did not differ on a number of important demographic characteristics (see Table 1). The three groups were equivalent in child age, F(2,221) = .72, n.s; child gender, χ2(2) = 5.16., n.s.; and family marital status, χ2(2) = 2.02, n.s.. In addition, the abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated families had comparable scores on Hollingshead's (1975) four factor index of social status, with 79% of the families in the abused group, 70% of the families in the neglected group, and 70% of the families in the nonmaltreated group falling in the two lowest social strata, χ2 (2) = 2.00, n.s.. Children also demonstrated comparable cognitive performance on the Peabody Picture Verbal Test, Revised (PPVT-R; Dunn & Dunn, 1981), F(2, 221) = 1.99, n.s. The groups significantly differed on ethnicity, χ2 (6) = 42.41, p <.001, such that 75.0% of the nonmaltreated group was comprised of African-American children, in comparison to 31.7% of the abused and 60.6% of the neglected groups. To control for this difference, ethnicity was covaried in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics for Abused, Neglected and Nonmaltreated Children

| Abused (N= 63) | Neglected (N = 33) | Non-Maltreated (N = 128) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or % | M(SD) or % | M(SD) or % | |

| Mean Child Age | |||

| Years | 9.90(1.35) | 10.28(1.70) | 10.02(1.45) |

| Child Gender | |||

| Male | 60.3% | 72.7% | 51.6% |

| Female | 39.7% | 27.3% | 48.4% |

| Family Marital Status | |||

| Single | 60.3% | 60.6% | 69.5% |

| Ethnicity** | |||

| African American | 31.7%a | 60.6%b | 75.0%b |

| European American | 60.3% | 30.3% | 18.8% |

| Hispanic American | 6.3% | 0% | 3.9% |

| Other | 1.6% | 9.1% | 2.3% |

| SES(Hollingshead) | |||

| Lowest two social strata | 79.0% | 69.7% | 69.5% |

| Cognitive Performance | |||

| PPVT-R Standard Score | 82.00(18.8) | 86.42(13.8) | 86.99(15.9) |

Indicates significant group differences, see text for explanation

Indicates significant group differences, see text for explanation

* p < .05 (2-tailed)

p <.01

Procedure

Data for the current investigation were collected during a 6 week- long recreational program where research was conducted. Children attended the summer camp for one of the six weeks. Children were assigned to same-age, same-sex groups of peers and were supervised by adult counselors who were unaware of the children's maltreatment status and of the research hypotheses. On the first day of camp, children were informed of the opportunity to participate in research and were asked to provide assent for their participation. At this time, confidentiality of children's responses, and its limits, was explained. During the program, children were individually interviewed by trained research staff, who were also unaware of child maltreatment status or study hypotheses, in order to obtain assessments relevant to memory and self representation. Additionally, the counselors completed assessment instruments at the conclusion of the camp week, after 35 hours of observation with the children.

Measures

Maltreatment Classification System (MCS)

Dimensions of family maltreatment were determined by trained coders using the MCS (Barnett et al., 1993). Rather than relying on child protective agency designation, reports of the children's experiences, as documented in child protective and preventive records and via maternal interview, were used for coding. Utilizing the well- validated MCS (e.g., Bolger, Patterson, & Kupersmidt, 1998; English, Bangdiwala, & Runyan, 2005; Manly, 2005; Manly et al., 1994), coders classified children's maltreatment experiences according to subtype(s); multiple subtypes could be coded for each report.

Maltreatment subtype categories included sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, and emotional maltreatment. The presence of sexual abuse was coded when any sexual contact or attempted sexual conduct occurred between the child and an adult. These behaviors range from exposure to inappropriate sexual activities to forced intercourse. Physical abuse was determined by injuries that had been inflicted upon a child by nonaccidental means. These incidents could range from excessive corporal punishment leading to bruising, to permanently disfiguring injuries. Physical neglect was coded “when the primary caregiver failed to meet a child's needs for food, clothing, shelter, medical, dental, or mental health care, education, hygiene, or physical safety” (Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001). Typical neglect incidents included leaving young children at home alone, maintaining unsanitary living conditions, and providing inadequate nourishment. Emotional maltreatment was coded for chronic or extreme neglect or disregard of children's emotional needs. This includes the need for acceptance and self-esteem, psychological security, and age-appropriate autonomy. Examples of emotionally maltreating events included serious threats to injure a child, exposure to violent acts among family members, and abandonment by primary caregivers. (See Barnett et al., 1993 for a detailed description of the nosological system used to code incidents of maltreatment).

The perpetrator of maltreatment was also documented. The child's biological mother was named as a perpetrator of maltreatment for 96.8% of the abused children and 93.9% of the neglected children, χ2(1) = .45, n.s. Coding of DHS records for dimensions of child maltreatment were conducted by trained research assistants and Ph.D. level psychologists among whom adequate reliability was established (weighted κ = .78- 1.0).

Levels of Processing Task/Depth of Processing (LOP; Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1995)

Children's encoding of and memory for mother-referent attribute words was assessed through the Levels Of Processing Task (LOP), a measure that was adapted by Rudolph and colleagues (1995) from a similar paradigm developed and validated by Hammen and Zupan (1984) to assess children's processing of self-referent adjectives. Forty-four words (22 positive and 22 negative adjectives), with word frequency and length equalized, were verbally and visually presented one at a time to the children. Words were presented under one of two encoding conditions: structural (“Does this word have big letters?”) or mother-referent (“Does this word describe your mom?”). As soon as children's yes or no response was recorded for an item the next word was presented. An unexpected incidental recall period immediately followed. Children were asked to recite as many of the previously presented words as possible, in any order.

The encoding conditions were randomized so that all words were presented equally under structural and self-referent instructions. Furthermore, the task involved two versions that were administered to children to counterbalance the encoding condition asked about each word. Thus, children were presented with a list that contained four groups of 11-words: positive structural, positive mother-referent, negative structural and negative mother-referent. One word from each of these groups was presented as one of the first two or last two words; these four words were then excluded from analysis to minimize primacy and recency memory effects.

Depression Ratings

Teacher's Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (TRF; Achenbach, 1991)

Counselors, who were unaware of children's maltreatment status or of the study hypotheses, used the TRF to rate children's behaviors after approximately 35 hours of observation. The TRF is a well-validated instrument that includes 118 items rated for the frequency of occurrence of problem behaviors and includes two broad dimensions of child symptomatology: internalizing and externalizing. Although counselors reported on both dimensions, this investigation focused only on internalizing symptomatology (e.g., withdrawal, somatic complaints and anxiety-depression). Individual child scores for internalizing symptomatology reflected the sum of the average of three counselor's scores for each child. Interrater reliabilities (intraclass correlations) ranged from .66 to .84.

Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1981)

In addition to the TRF, which provides an observer report of child symptomatology, the CDI was administered so that children could have the opportunity to report on their own perceptions of their depressive symptoms. The CDI contains 27 items that assesses the cognitive, affective and behavioral sequelae of depression, and has acceptable reliability and validity (Kovacs, 1992). Scores on the CDI may range from 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptomatology. Typically, scores greater than 12 on the CDI are conceptualized as reflecting mild depression, whereas scores of 19 or greater signify clinical levels of depression (Smucker, Criaghead, Wilcoxan, Craighead, & Green, 1986)

Cognitive Performance

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-R, Dunn & Dunn, 1981)

Because memory recall may be related to general intelligence and language abilities, a cognitive assessment was administered to all participants. The PPVT-R is an individually administered, multiple- choice test designed to assess the receptive vocabulary skills of persons aged 2.5 through 90+ years and it correlates highly with several measures of intelligence. The correlation of PPVT-R and WISC-R = .70 (Dunn & Dunn, 1997).

Results

Data Reduction

For each participant, the number of words recalled as a function of task instructions (mother referent or structural) and rating (yes or no) was calculated, excluding the four buffer items (Hammen & Zupan, 1984; Rudolph et al., 1995). Noting that yes-rated words are generally better recalled than no-rated words (Craik & Tulving, 1975; Hammen & Zupan, 1984; Rogers, 1981), the recall data were transformed into proportion scores (e.g., number of yes rated words recalled under a mother-referent condition/number of yes-rated words in that rating task; number of yes-rated words recalled under a structural condition/number of yes-rated words in that rating task; number of no- rated words recalled under a mother-referent condition/number of no-rated words in that rating task; number of no-rated words recalled under a structural condition/number of no-rated words in that rating task). These proportion scores were created for both positive and negative conditions, resulting in 8 total proportion scores. Additionally, to reflect the relative negativity of maternal- schema, a summary score was calculated for each participant as the proportion of yes-rated negative maternal- referent words recalled minus the proportion of yes-rated positive maternal- referent words recalled. Based on this negativity index score, children were divided into two groups: a positive maternal schema group (those with index scores < 0) and a negative maternal schema group (those with index scores ≥ 0) (Hammen & Zupan, 1984; Rudolph et al., 1995). Finally, a separate negativity index score was created for children's recall of structurally encoded words, using the proportion of yes-rated negative structural words recalled minus the proportion of yes-rated positive structural words recalled. Children were again divided into two groups: a positive structural schema group (index scores < 0) and a negative structural schema group (index scores > 0).

Memory Analyses

To assess our first hypothesis regarding whether memory performance varied among children who have been abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated, an instruction (maternal referent/structural) x rating (yes/no) repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) on proportion scores was conducted with subtype (abused/neglected/nonmaltreated) as the between subjects variable. Child age, ethnicity, and cognitive performance (PPVT-R standard scores) were included as covariates. Examination of the within-subjects analyses revealed a significant main effect of instructional task, F (1, 211) = 6.28, p <.05, such that children's recall was greater under mother-reference instructions (M = .17, SD = .12) than under structural conditions (M = .11, SD = .07). This pattern is consistent with prior research that has utilized depth-of-processing paradigms among children (e.g., Hammen & Zupan, 1984; Rudolph et al., 1995), and replicates findings among samples of maltreated children (Valentino et al., in press). The main effect of rating was nonsignificant, as was the instruction by rating interaction.

Examination of the between-subjects effects revealed that age was a significant covariate, F(1, 211) = 24.61, p < .001. Cognitive performance was also a significant covariate, F(1, 211) = 9.07, p < .01. Ethnicity, however, was not significantly related to children's recall performance, F(1, 211) = .70, n.s.

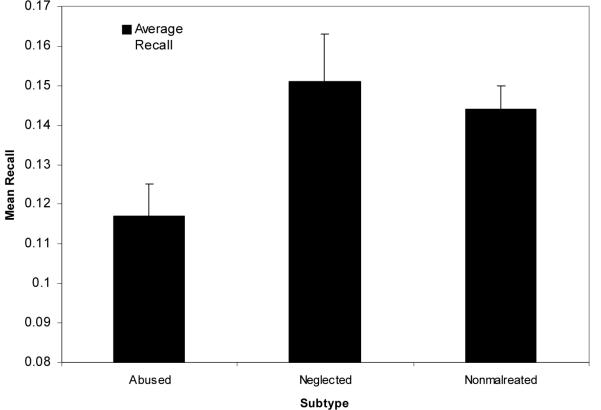

Controlling for age, cognitive performance and ethnicity, a significant main effect of maltreatment subtype emerged, F(2, 211) = 3.92, p <.05 (see Figure 1). Subsequent pairwise comparisons, Bonferroni corrected, revealed that the abused children demonstrated lower average recall (M = .12, SD = .07) than did the nonmaltreated children (M= .14, SD = .07, p <.01), and marginally less than the neglected children (M = .15 SD = .07, p < .06). Recall between the neglected and nonmaltreated children did not significantly differ. The interaction of subtype and age group was nonsignificant as were the interactions of subtype with instruction task and rating. Therefore, the experience of maltreatment did not have an impact on children's ability to use maternal-schema to facilitate recall. However, abuse, in particular, was related to lower overall memory performance.

Figure 1.

Memory: Average mean recall and standard error by maltreatment subtype.

It is particularly noteworthy that 86% of the abused group experienced physical abuse; moreover, 65.4% of children who were sexually abused were also physically abused. Nonetheless, potential differences between sexually abused and physically abused children's memory performance were explored. The abused group was separated into a Sexual Abuse (SA) group and Physical Abuse (PA) group, where children who experienced sexual abuse were placed into the SA group irrespective of concomitant physical abuse. A repeated-measures analysis on children's recall, controlling for age, ethnicity and children's PPVT scores was conducted and the main effect of subtype for overall recall remained significant F(3, 216) = 3.28, p < .05. Subsequent pairwise comparisons revealed that the SA (M = .119, SD = .07) and PA groups (M = .113, SD = .07) did not significantly differ in memory performance, p = n.s. In addition, among those children with SA, those who also experienced PA (N = 17) were compared to those who experienced SA but not PA (N = 9); again no differences in memory performance were revealed, F (1, 20) = .307, p = n.s. In light of these findings, which demonstrate a lack of significant differences between sexually abused and physically abused children's memory performance, we continue to classify maltreated children as “abused” or “neglected” throughout the data analyses.

To evaluate our second hypotheses, a χ2 analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between maltreatment experiences and the affective valence of children's maternal schema. Results indicated that abused, neglected and nonmaltreated children did not differ in the affective valence of their maternal schema, χ2(2)= .32, n.s., such that 68.7% of the abused children demonstrated positive maternal schema in comparison to 63.6% of the neglected children and 62.5% of the nonmaltreated children. A further comparison of children's maternal schema was performed via an ANOVA on children's maternal negativity index score as a function of maltreatment subtype. Results confirmed that abused, neglected and nonmaltreated children did not differ in the negativity of their maternal schema, F(2, 221) = .016, n.s.

Maternal Schema, Maltreatment and Depressive/Internalizing Symptomatology

Next, we tested the hypothesis that children's processing of mother-relevant information would be associated with their depressive symptomatology, and that this relationship might differ by subtype of maltreatment experienced. Because prior research has reported gender differences in children's coping styles under conditions of extreme or chronic stress (e.g., Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990), and has indicated significant differences in the relation between gender and depression, (e.g., Mesman, Bongers, & Koot, 2001; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001), gender was entered as a covariate in all depression analyses.

Of the 224 children who completed the LOP measure, 17 did not complete the CDI. Because there were no differences by maltreatment subtype among those who did not provide recall, χ2 (2) = 1.29, n.s, these 17 children were dropped from further analyses. Children's performance on the CDI was significantly correlated with counselor's ratings of internalizing behavior, r = .165, p < .05.

A multivariate analysis of covariance was conducted upon depression scores (CDI and Internalizing T-score from TRF) where maltreatment subtype (abused/neglected/nonmaltreated), and valence of maternal-schema (positive/negative) served as the independent variables, controlling for age, gender, and ethnicity. The main effect of subtype upon depression scores was significant, F(4, 396) = 5.09, p < .001. However, this was qualified by a significant multivariate interaction of subtype x schema, F (4, 396) = 4.22, p < .01 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Child depression and internalizing scores: Subtype by maternal schema

| Maternal Schema | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| M(SD) | N | M(SD) | N | |

| CDI | ||||

| Abused | 7.9(6.1) | 31 | 7.3(6.6) | 25 |

| Neglected* | 4.5(4.5) | 20 | 10.7(7.7) | 11 |

| Nonmaltreated | 7.1(6.3) | 77 | 6.1(4.7) | 43 |

| Internalizing T-score | ||||

| Abused | 53.37(9.0) | 31 | 56.10(6.8) | 25 |

| Neglected* | 49.79(6.2) | 20 | 55.64(9.1) | 11 |

| Nonmaltreated | 50.29(7.2) | 77 | 47.57(7.2) | 43 |

p < .05 (2-tailed)

Subsequently, a separate univariate ANCOVA on CDI, controlling for gender, age, and ethnicity was conducted. The interaction of subtype x schema was significant, F(2, 198) = 4.35, p <.05. Simple effects analyses of the subtype x schema interaction revealed that the manner in which the valence of maternal schema related to depression differed as a function of maltreatment subtype. Among the neglected children, those with negative maternal- schemas evidenced significantly higher CDI scores (M = 10.73, SD = 7.7) than those with positive maternal-schema (M = 4.49, SD = 4.5, p < .05). However, among the abused children, those with negative maternal-schemas (M = 7.33, SD = 6.6) did not differ from those with positive maternal- schemas (M= 7.88, SD = 6.1). Among the nonmaltreated children there were also no significant differences in CDI scores between those with negative (M = 6.07, SD = 4.7) and positive (M = 7.08, SD = 6.3) maternal- schemas

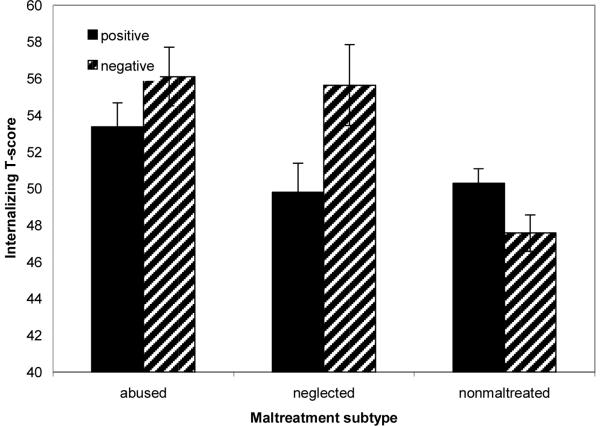

A parallel univariate ANCOVA was performed upon TRF Internalizing T- scores, with maltreatment subtype and maternal- schema as the independent variables, and gender, age, and ethnicity as the covariates. A significant subtype main effect emerged, F(2, 198) = 10.48, p <.001, such that abused children (M = 54.74, SD = 8.14) and neglected children (M = 52.72, SD = 7.93) each demonstrated more internalizing symptomatology than did nonmaltreated children (M = 48.93, SD = 7.26), p <.05. This was qualified by a significant subtype x schema interaction F(2, 198) = 4.89, p < .01 (see Figure 2). Further examination of the subtype x schema interaction again revealed that neglected children with negative maternal- schemas evidenced higher Internalizing symptoms (M = 55.64, SD = 9.1) than neglected children with positive maternal- schemas (M = 49.79, SD = 6.2). In contrast, abused children and nonmaltreated children did not demonstrate significant differences in Internalizing symptoms as a function of the affective valence of their maternal- schema.

Figure 2.

Internalizing T-scores and standard error by maternal schema for abused, neglected and nonmaltreated children.

To ensure that the interaction effect of maternal- schema and maltreatment subtype upon children's psychopathology was specific to representations of mother, an additional multivariate analysis was conducted where maternal- schema was replaced by structural- schema as a dependent variable. That is, a multivariate analysis of variance was performed upon CDI and Internalizing scores, where maltreatment subtype and valence of structural- schema served as the independent variables, with gender, age, and ethnicity as the covariates. Confirming that the maternal- schema effects noted in our previous set of analyses were specific to maternal representations, the interaction of structural- schema x subtype was nonsignificant, F(4, 396) = 1.18, n.s.. Similarly, the main effect of structural- schema was nonsignificant, F(2, 197) = .27, n.s..

Discussion

The results of the current study advance our understanding of the role of representational models in the association between maltreatment, memory, and internalizing symptomatology. Specifically, this investigation enhances our knowledge regarding the manner in which the experience of trauma affects basic memory processes by examining memory for maternal-referent and emotionally valenced stimuli. In addition, the utilization of a depth-of-processing incidental recall paradigm enabled us to address self-report limitations of prior investigations by assessing maternal- representations in an implicit manner.

Memory

Abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated children all displayed the depth-of-processing effect such that words encoded under maternal-referent conditions were better remembered than were words encoded under structural conditions. In other words, all children were able to use the mother-referent instructions to facilitate recall, providing evidence that maternal- representations function as an organizing schema for memory. These findings are consistent with prior assessments of the depth-of-processing task conducted among normative (Hammen & Zupan, 1984; Rudolph et al., 1995), and at- risk samples (Valentino et al., in press).

In support of our first hypothesis, abused, neglected and nonmaltreated children evidenced significant differences in recall performance. Specifically, abused children demonstrated lower average recall than did the neglected children and the nonmaltreated children. This difference in memory performance represents the first evidence of impairment in nontraumatic, semantic memory recall detected among a subgroup of maltreated children.

The finding that abused children, in particular, display impairments in recall performance is consistent with other studies that have been conducted among a subset of traumatized children and adults who additionally manifest PTSD (e.g., Beers & DeBellis, 2002). Furthermore, studies of autobiographical memory and general cognitive processing among adults suggest that the experience of trauma is associated with poorer memory for autobiographical events (Henderson et al., 2002; McNally, Lasko, Macklin, & Pitman, 1995). Therefore, it seems that the trauma of child abuse may have a negative impact upon children's memory processes, whereas the experience of neglect may not.

Although the findings of this investigation differ from the extant research that has supported preserved basic memory processes among maltreated children, the aforementioned research has focused on memory for neutral stimuli (Howe et al., 2004) and for self-referent stimuli (Valentino et al, in press), whereas this investigation extended the range of to-be-remembered information to maternal- referent stimuli. One explanation for memory impairments among abused children during this paradigm may be that mother-referent stimuli activate children's attachment systems while neutral and self-referent stimuli do not. Thus, consistent with the theoretical views of Main (1990), abused children who are regularly rejected by their caregivers may develop cognitive strategies that reduce their attention and memory for attachment related stimuli to protect themselves from experiencing negative emotion. Therefore, in the current investigation it is possible that repeated reference to children's mothers activated children's attachment system throughout the memory task, affecting the abused children's ability to recall all words, not just those that were encoded under mother-referent conditions.

Furthermore, it may be the case that abused children interpret maternal-referent stimuli as stressful or threatening, and that the impairments in memory performance observed among abused children might reflect attentional and memory processes that are elicited in response to stressful experiences in general. Empirical evidence that demonstrates a tendency among maltreated children to shift their attentional focus away from aggressive stimuli in contrast to nonagressive stimuli (Rieder & Cicchetti, 1989) supports such an interpretation because this attentional strategy will negatively impact the encoding and subsequent recall of the threatening experience. It is important to note that in the current investigation, repeated reference to maternal stimuli was related to abused children's recall of all words, not just for words encoded under maternal reference. Therefore, one question for future research is to determine whether impairments in abused children's memory performance are specific to maternal-relevant stimuli or are reflective of a more general pattern of response to stressful or threatening experiences.

Schema

Abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated did not demonstrate differences in the affective valence of their maternal- schema. As such, abused and neglected children did not differ in the affective valence of maternal-referent words that were recalled. In light of evidence that the story-stem narratives of abused preschoolers contain increased rates of negative maternal representations (Toth et al., 1997), we had expected that abused children, in particular, would be more likely to demonstrate negative schema than would neglected and nonmaltreated children. Nonetheless, the lack of differences in affective valence of maternal- schema, as assessed through this depth-of-processing paradigm, is consistent with findings regarding rates of positive maternal and self- schema assessed via children's narratives (Toth et al., 1997), and with the affective valence of self-schema assessed through a similar depth-of-processing paradigm (Valentino et al., in press). Given evidence that maltreated children have a tendency to inhibit negative affect, displaying false positive affect instead (Beeghly & Cicchetti, 1994; Crittenden & DiLalla, 1988; Koenig, Cicchetti, & Rogosch, 2000), it is possible that similar defensive processes are masking the detection of affective differences in maternal- schema in this sample.

Schema and Depression

To further examine the manner through which representational models are associated with psychopathology among maltreated children, the role of positive and negative maternal- schemas was assessed in relation to internalizing symptomatology. Overall, children who have been abused demonstrated the most internalizing symptomatology in comparison to nonmaltreated children. Children who have been neglected also evidenced elevated internalizing symptoms in comparison to nonmaltreated children, although to a lesser degree than the abused children. These findings are consistent with a large body of research that has identified maltreated children as at high risk for the development of internalizing symptomatology (e.g., Bolger & Patterson, 2001; Manly, et al., 2001; Toth, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1992).

However, the significant interaction of maltreatment subtype and maternal- schema upon children's internalizing symptoms reveals that positive and negative maternal- representations have a differential impact on internalizing symptomatology as a function of maltreatment subtype experiences. The nonsignificant interaction effect of subtype and structural- schema upon internalizing symptoms corroborates that the interaction of maternal- schema and maltreatment subtype upon children's psychopathology was specific to maternal- representations.

In particular, the affective valence of maternal- schema had a significant relationship with internalizing symptomatology among the neglected children only. Neglected children with negative maternal- schemas demonstrated higher levels of internalizing symptoms than did neglected children with positive maternal- schemas. Evidence from both child-reported and counselor-reported internalizing symptoms cohered to support this pattern. In contrast, positive and negative maternal- schemas did not differentiate internalizing symptomatology among abused and nonmaltreated children. Therefore, it seems that negative maternal- schemas are a significant risk factor for neglected children, whereas the presence of positive maternal schemas can be an important protective factor against the development of internalizing symptoms. In contrast, the presence of positive maternal schemas does not appear to mitigate the development of internalizing symptoms among children who have been abused.

The unique relationship between the experience of physical neglect (as opposed to other forms of maltreatment) and the development of internalizing symptoms has been observed among other samples of maltreated children (Manly et al., 2001). Unlike physical or sexual abuse, which is usually incident-specific, child neglect is often a more pervasive phenomenon. Utilizing an attachment theory perspective to interpret the relation of neglect to internalizing symptomatology, Manly and colleagues suggest that children who have been neglected have formed representational models of their relationships as unlikely to meet their needs (Bretherton, 1991; Rogosch & Cicchetti, 1994; Shields et al., 2001). As such, children who have been neglected may expect that relationships will be unfulfilling and will often withdraw from social interactions (Manly et al., 2001). Therefore, the current investigation's finding that neglected children with negative- maternal representations are most at-risk for the development of internalizing symptomatology is consistent with, and provides empirical support, for what would be predicted by attachment theory.

The results of this investigation also suggest that positive maternal- representations may have a positive impact on mitigating against the development of internalizing symptoms. The extant research has indicated that for maltreated children, but not nonmaltreated children, positive perceptions of parents have a buffering effect in relation to the development of behavioral maladjustment (Toth & Cicchetti, 1996). The current investigation corroborates the protective nature of positive maternal- representations that has been detected in prior research and adds the analysis of maltreatment subtype experiences to identify that this buffering effect is particularly salient for neglected children.

Summary and Future Directions

In summary, abused children demonstrated impairments in memory performance in comparison to neglected and nonmaltreated children on a depth-of-processing incidental recall task for maternal-referent stimuli. Thus, this investigation extends the current literature on basic memory functioning among traumatized children, which has previously supported preserved basic memory processes for neutral and self-referent stimuli (Howe et al., 2004; Valentino et al., in press). Taken in tandem with results of the current investigation, research suggests that generally abuse does not affect basic memory functioning; however, under certain conditions such as those that activate children's attachment systems during encoding and/or recall, children who have been abused demonstrate poorer memory performance. In order to substantiate such an interpretation, this pattern of memory performance needs to be replicated among other samples of abused and neglected children. Ideally, future research will extend the range of stimuli to that which refers to persons other than mother, and will examine memory for mother-referent and non-mother-referent stimuli within a single investigation. Additionally, it will be important for future research to examine the severity of maltreatment in relation to memory performance. The inclusion of maltreatment severity may further clarify differences in memory performance between the neglected group and the abused group, where the likelihood of trauma is greater.

The identification of memory impairments among abused children has important implications for understanding the manner in which trauma affects children's memory as well as for assessment techniques. In particular, it will be important to determine the extent to which analog trauma paradigms, which typically do not activate children's attachment systems and/or assess memory for attachment relevant information, are generalizable to the understanding of memory functioning among maltreated children, whose traumas often occur within the context of their caregiving experience. Similarly, researchers may want to distinguish between caregiver-perpetrated and noncaregiver perpetrated traumas, as memory may be more adversely affected if the event is perpetrated by a caregiver.

Finally, the findings of this investigation have clear clinical implications for informing intervention and prevention programs aimed at protecting children from the effects of maltreatment. The poor recall performance displayed by the abused children may be reflective of attachment insecurity, which has been associated with several maladaptive developmental outcomes (e.g., van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakersman-Kranenburg, 1999). For example children with an avoidant attachment organization may have developed a self-protective tendency to suppress maternal-referent information, thereby reducing the number and strength of nodal connections for maternal- schema and impeding memory recall. Similarly, children with a disorganized attachment organization may be less able to use maternal-representations to facilitate encoding and recall of maternal referent information because their maternal-representations lack consistency and cohesiveness. In light of evidence that poor specificity in autobiographical memory recall is predictive of later depressive symptomatology in adolescence and/or adulthood, (Brittlebank, Scott, Williams, & Ferrier, 1993; Dalgleish, Spinks, Yiend, & Kuyken, 2001), the identification of memory impairments among abused children may be a useful way to target interventions towards children who are at higher risk for the development of internalizing psychopathology.

In addition, the importance of assessing children's representational models is highlighted, given the difference in internalizing symptomatology observed among neglected children with positive and negative maternal- representations. Intervention efforts that focus on helping children develop strategies to prevent the generalization of negative maternal- representations to other potentially positive relationship figures may lead to reduced internalizing symptoms for maltreated children, and may prove especially effective for children who have experienced neglect. Moreover, our current findings underscore the necessity of providing for the needs of children who have been victimized by neglect in addition to those who have been physically or sexually abused.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH068413) to Dante Cicchetti and Sheree Toth. The authors wish to thank Carol Ann Dubovsky for her invaluable assistance with this project.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist - teacher's report form. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KW, Edelstein RS. Children's attachment and memory for an experienced event. the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Minneapolis, MN. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KW, Quas JA, Goodman GS. Theoretical advances in understanding children's memory for distressing events: The role of attachment. Developmental Review. 2002;22:490–519. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KW, Quas JA, Goodman GS, Ghetti S, Edelstein R, Redlich A, et al. Traumatic impact predicts long-term memory of documented child sexual abuse. Psychological Science. 2005;16:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar ST. Parenting and child maltreatment. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 4. Erlbaum; Mahwah, N.J.: 2002. pp. 361–388. Social conditions and applied parenting. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DA. Clarifying the role of shape in children's taxonomic assumption. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1992;54:392–416. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(92)90027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment, attachment, and the self system: Emergence of an internal state lexicon in toddlers at high social risk. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Beers SR, DeBellis MD. Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):483–486. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Spritz B, Crnic K. Infant attachment security and affective-cognitive information processing at age 3. Psychological Science. 1996;7:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Pathways from child maltreatment to internalizing problems: Perceptions of control as mediators and moderators. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:913–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self-esteem among chidlren who have been maltreated. Child Development. 1998;69:1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD. Neuroimaging of childhood trauma. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7:104–112. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2002.31787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Functional neuroanatomical correlates of the effects of stress on memory. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:527–553. doi: 10.1007/BF02102888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Narayan M. The effects of stress on memory and the hippocampus throughout the life cycle: Implications for childhood development and aging. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:871–885. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Pouring new wine into old bottles: The social self as internal working model. In: Gunnar M, Sroufe LA, editors. Minnesota symposia on child psychology: Self processes and development. Vol. 2. Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships; A construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Brittlebank AD, Scott J, Williams JMG, Ferrier IN. Autobiographical memory in depression: State or trait marker? British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;162:118–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo MA. Abusive family interaction: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. How research on child maltreatment has informed the study of child development: Perspectives from developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1989. pp. 377–431. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Manly JT. A personal perspective on conducting research with maltreating families: Problems and solutions. In: Brody G, Sigel I, editors. Methods of family research: Families at risk. Vol. 2. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Valentino K. An Ecological Transactional Perspective on Child Maltreatment: Failure of the Average Expectable Environment and Its Influence Upon Child Development. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology (2nd ed.): Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Vol. 3. Wiley; New York, New York: 2006. pp. 129–201. [Google Scholar]

- Craik FLM, Tulving E. Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, General. 1975;104:268–294. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15(3):719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM, DiLalla D. Compulsive compliance: The development of an inhibitory coping strategy in infancy. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;16:585–599. doi: 10.1007/BF00914268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgliesh T, Spinks H, Yiend J, Kuyken W. Autobiographical memory style in seasonal affective disorder and its reltionship to future symptom remission. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:335–340. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBellis MD, Keshavan MS, Casey BJ, Clark DB, Giedd J, Boring AM, et al. Developmental traumatology: Biological stress systems and brain development in maltreated children with PTSD part II: The relationship between characteristics of trauma and psychiatric symptoms and adverse brain development in maltreated children and adolescents with PTSD. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:1271–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody picture vocabulary test-revised. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody picture vocabulary test. 3rd ed. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eisen ML, Goodman GS, Qin J, Davis SL. Maltreated children's memory: Accuracy, suggestibility, and psychopathology. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2005 doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen ML, Qin J, Goodman GS, Davis SL. Memory and suggestibility in maltreated children: Age, stress arousal, dissociation and psychopathology. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2002;83:167–212. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0965(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DE, Bangdiwala SI, Runyan DK. The dimensions of child maltreatment: introduction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(5):441–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman GS. Wailing babies in her wake. American Psychologist. 2005:872–881. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.8.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman GS, Quas JA. Trauma and memory: Individual differences in children's recounting of a stressful experience. In: Stein NL, Ornstein A, Tversky B, Brainerd CJ, editors. Memory for everyday and emotional events. Erlbaum; Mahwah: NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhoot AF, McCloskey L, Glisky E. A longitudinal study of adolescents' recollections of family violence. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2005;19:719–743. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Zupan B. Self-schemas, depression, and the processing of personal information in children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1984;37:598–608. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(84)90079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D, Hargreaves I, Gregory S, Williams JMG. Autobiographical memory and emotion in a nonclinical sample of women with and without a reported history of childhood sexual abuse. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:129–141. doi: 10.1348/014466502163921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Four-factor index of social status. 1975 Unpublished manuscript, Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML. Individual differences in factors that modulate storage and retrieval of traumatic memories. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:681–698. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML. The fate of early memories: Developmental science and the retention of childhood experiences. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML, Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Cerrito BM. True and false memories in maltreated children. Child Development. 2004;75(5):1402–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML, Courage ML. The emergence and early development of autobiographical memory. Psychological Review. 1997;104(3):499–523. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML, Courage ML, Peterson C. How can I remember when “I” wasn't there: Long-term retention of traumatic experiences and the emergence of the cogntive self. Consciousness and Cognition. 1994;3:327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML, Courage ML, Peterson C. Intrusions in preschooler's recall of traumatic childhood events. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1995;2:130–134. doi: 10.3758/BF03214419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe ML, Toth SL, Cicchetti D. Memory and Developmental Psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental Psychopathology. 2nd Edition. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 629–655. Developmental Neuroscience. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsh SJ, Cassidy J. Preschooler's attention to and memory for attachment-relevant information. Child Development. 1997;68:1143–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig AL, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Child compliance/noncompliance and maternal contributors to internalization in maltreating and nonmaltreating dyads. Child Development. 2000;71:1018–1032. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatrica. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Multi-Health Systems; New York: 1992. Children's Depression Inventory: Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Cross-cultural studies of attachment organization: Recent studies, changing methodologies and the concept of conditional strategies. Human Development. 1990;33:48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy JC. Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Growing pointsof attachment theory and research. Vol. 209. Society for Research in Child Development Monograph; MA: 1985. pp. 66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT. Advances in research definitions of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(5):425–439. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Cicchetti D, Barnett D. The impact of subtype, frequency, chronicity, and severity of child maltreatment on social competence and behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H. Self-schemas and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1977;35:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best K, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey L, Figueredo A, Koss M. The effects of systemic family violence on children's mental health. Child Development. 1995;66:1239–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; McNally RJ. Experimental approaches to cognitive abnormality in posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18(8):971–982. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ, Lasko NB, Macklin ML, Pitman RK. Autobiographical memory disturbance in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1998;33:619–630. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Bongers IL, Koot HM. Preschool developmental pathways to preadolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2001;42:679–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(5):173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim D, Emde RN, Warren S. Children's narrative representations of mothers: Their development and associations with child and mother adaptation. Child Development. 1997;68:127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter C, Lawson JS, Bigler ED. Neurobehavioral sequelae of child sexual abuse. Child Neuropsychology. 2005;11(2):203–220. doi: 10.1080/092970490911379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder C, Cicchetti D. Organizational perspective on cognitive control functioning and cognitive-affective balance in maltreated children. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:382–393. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TB. A model of the self as an aspect of the human information processing system. In: Cantor J, Kihlstrom N, editors. Personality, cognition and social interaction. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Illustrating the interface of family and peer relations through the study of child maltreatment. Social Development. 1994;3:291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Cognitive representations of self, family, and peers in school-age children: Links with social competence and sociometric status. Child Development. 1995;66(5):1385–1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran JD. Towards a refinement of cognitive therapy in light of interpersonal theory: I. Theory. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Stress, the aging brain, and the mechanisms of neuron death. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:349–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Ryan RM, Cicchetti D. Narrative representations of caregivers and emotion dysregulation as predictors of maltreated children's rejection by peers. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:321–337. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Bruce J, Kane P, Daddis C. Maltreated and nonmaltreated preschoolers' conceptions of hypothetical and actual moral trangressions. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:269–281. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Wilcoxan Craighead L, Green BJ. Normative and reliability data for the Children's Depression Inventory. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Infant-caregiver attachment and patterns of adaptation in preschool: The roots of maladaptation and competence. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota symposium in child psychology. Vol. 16. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. pp. 41–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Relationships, self, and individual adaptation. In: Sameroff A, Emde RN, editors. Relationship disturbances in early childhood. Basic Books; New York: 1989. pp. 70–94. [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D. Patterns of relatedness and depressive symptomatology in maltreated children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:32–41. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Kim JE. Relations among children's perceptions of maternal behavior, attributional styles, and behavioral symptomatology in maltreated children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:478–501. doi: 10.1023/a:1019868914685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Macfie J, Emde RN. Representations of self and other in the narratives of neglected, physically abused, and sexually abused preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:781–796. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Macfie J, Maughan A, VanMeenan K. Narrative representations of caregivers and self in maltreated preschoolers. Attachment and Human Development. 2000;2:271–305. doi: 10.1080/14616730010000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment and vulnerability to depression. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, McBride-Chang C. The developmental impact of different types of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Review. 1995;15:311–337. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino K, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. True and false memory and dissociation among maltreated children: The role of self schema. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000102. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Schuengel C, Bakersman-Kranenburg MJ. Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analyses of precursors concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:225–249. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]