INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma is a malignant plasma cell disorder that accounts for approximately 10% of all hematologic cancers.1,2 It is felt to evolve from an asymptomatic pre-malignant stage of clonal plasma cell proliferation termed monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). MGUS is present in over 3% of the population above the age of 50, and progresses to myeloma or related malignancy a rate of 1% per year.3,4 In some patients, an intermediate asymptomatic but more advanced pre-malignant stage referred to as smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) can be recognized clinically.

The annual incidence of myeloma, age-adjusted to the 2000 United States population, is 4.3 per 100,000. 5 Almost 20,000 new cases and 11,000 new deaths are estimated to occur in the United States in 2007.6 Multiple myeloma is twice as common in African-Americans compared to Caucasians, and slightly more common in males than females.

The median age at diagnosis is 66 years.7 The most common presenting symptoms are fatigue and bone pain.7 Osteolytic bone lesions and/or compression fractures are the hallmark of the disease, and cause significant morbidity. Anemia occurs in 70% of patients at diagnosis and is the primary cause of fatigue. Renal dysfunction is occurs in 50% and hypercalcemia in 25% of patients.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Initial Description of the disease

Although multiple myeloma has most likely been present for thousands of years, the first well-documented case was a patient, Sarah Newbury, described by Solly in 18448. Later, the case of Thomas Alexander McBean, led to the discovery of the Bence Jones protein in the late 1840s.9-12 Multiple myeloma is sometimes referred to as Kahler’s disease following a case report by Professor Otto Kahler. The term “plasma cell” was introduced by Waldeyer in 1875,13 but it was Ramon y Cajal, the neuroanatomist, to first accurately describe the plasma cell. In 1895, Marschalko, published the best description of plasma cells which included blocked chromatin, eccentric position of the nucleus, a perinuclear pale area (hof) and a spherical or irregular cytoplasm. Wright 14 was among the first to state that the tumor cells of myeloma consisted of plasma cells or immediate descendants of these cells. The first large case series of myeloma (n=412) was reported by Geschickter and Copeland.15

Monoclonal Proteins

Hyperproteinemia was first demonstrated in multiple myeloma in 1928 by Perlzweig et al 16. The term Bence Jones protein was first used by Fleischer in 1880.17 In 1922, Bayne-Jones and Wilson 18 described the existence of two distinct groups of Bence Jones protein. The group of light chains were later characterized by Korngold and Lipari using the Ouchterlony test in 1956.19 As a tribute to Korngold and Lipari, the two classes of Bence Jones proteins were subsequently designated kappa and lambda. In 1937, Tiselius20 separated serum globulins into three components: alpha, beta, and gamma. In 1939, Tiselius and Kabat 21 demonstrated that the gamma globulin fraction consisted of antibodies. The tall, narrow-based, “church spire” peak on serum protein electrophoresis characteristic of multiple myeloma was recognized in 1939 22. Immunoelectrophoresis was described by Grabar and Williams in 1953,23 and eleven years later, immunofixation was introduced by Wilson 24. Immunofixation is now the most commonly used approach for the identification of monoclonal proteins. The concept of monoclonal versus polyclonal gammopathies was enunciated by Jan Waldenstrom in 1961.25

Alkylator and Corticosteroid Based therapy

Rhubarb pill and infusion of orange peel is the first documented treatment for myeloma, administered to Sarah Newbury in 1844. Mr. McBean was treated with phlebotomy, with the application of leeches used as “maintenance therapy.” Later, he was treated with steel and quinine.8,9,26 Urethane introduced by Alwall in 1947 was the standard of therapy for more than 15 years.27 But urethane was discarded in 1966 when Holland et al. 28 randomized 83 patients with treated or untreated multiple myeloma to receive urethane or a placebo consisting of cherry and cola-flavored syrup and found no difference in the objective status or survival between the two treatment groups.

Melphalan (sarcolysin), a mainstay of therapy even today, was first introduced in 1958 by Blokhin et al.29 He found benefit in three of six patients with multiple myeloma. Later, in 1962, Bergsagel et al.30 reported significant improvement in 8 of 24 patients with multiple myeloma who were treated with melphalan.

In 1967, prednisone was reported by Maas et al to produce benefit in 8 of 10 patients with poor-risk myeloma.31 In a placebo-controlled double-blind trial, prednisone as a single agent produced significant decreases in serum globulin and an increase in hematocrit but no difference in survival when compared with a placebo.32 In a reanalysis of 2 CALGB myeloma treatment protocols, prednisone as a single agent produced a 44% objective response rate 33.

In 1969, Alexanian found in a randomized trial of 183 myeloma patients that survival was 6 months longer with melphalan and prednisone than melphalan alone, giving rise to the classic melphalan-prednisone (MP) regimen.34 For the next 30 years, numerous chemotherapy combinations were compared to MP in an attempt to improve on overall survival, without avail. In a large meta-analysis of over 20 randomized trials comparing melphalan and prednisone with various combinations of therapeutic agents, response rates were significantly higher with combination chemotherapy (60%) compared with melphalan and prednisone (53%) (P< 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in overall survival 35. It is only recently with the arrival of stem cell transplantation and novel agents as described below that improvements in overall have occurred in myeloma.

Stem Cell Transplantation

In 1957, Thomas et al. treated 6 human patients (1 of whom had multiple myeloma) with TBI or chemotherapy followed by an intravenous infusion of bone marrow cells.36. McElwain & Powles reported the first successful cases of autologous bone marrow transplantation in myeloma.37 Subsequently, Barlogie developed a series of treatment programs using autologous transplantation (“total therapy I, II and III”) that played a major role in establishing high-dose therapy and stem cell rescue as standard therapy for myeloma.

DISEASE DEFINITION

The disease definition for myeloma has undergone multiple revisions over the years. The current definition requires 10% or more clonal plasma cells on bone marrow examination (or biopsy proven plasmacytoma), M protein in the serum and/or urine (except in patients with true non-secretory myeloma) and evidence of end-organ damage (hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, or bone lesions) that is felt to be secondary to the underlying plasma cell disorder.38,39 Table 1 provides the diagnostic criteria for myeloma, as well as related clonal plasma cell disorders that must be entertained in the differential diagnosis and distinguished from myeloma.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for Plasma Cell Disorders

| Disorder | Disease Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) | All 3 criteria must be met:

|

38 |

| Smoldering multiple myeloma (also referred to as asymptomatic multiple myeloma) | Both criteria must be met:

|

38 |

| Multiple Myeloma | All 3 criteria must be met except as noted:

|

38,271 |

| Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia | Both criteria must be met:

|

272-276 |

Note: IgM MGUS is defined as

|

||

| Solitary Plasmacytoma | All 4 criteria must be met

|

277,278 |

| Systemic AL Amyloidosis | All 4 criteria must be met:

|

39 |

| Note: Approximately 2-3 percent of patients with AL amyloidosis will not meet the requirement for evidence of a monoclonal plasma cell disorder listed above; the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis must be made with caution in these patients. | ||

| POEMS Syndrome | All 3 criteria must be met:

|

279 |

| Note: Not every patient meeting the above criteria will have POEMS syndrome; the features should have a temporal relationship to each other and no other attributable cause. The absence of osteosclerotic lesions should make the diagnosis suspect. Elevations in plasma or serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and thrombocytosis are common features of the syndrome and are helpful when the diagnosis is difficult. | ||

Modified, reproduced with permission from Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA. Mayo Clinic Proc 2006;81:693-703. © Mayo Clinic Proceedings39.

PATHOGENESIS

Evolution of MGUS

The first step in myeloma pathogenesis is the establishment of MGUS, a precursor lesion that precedes almost all cases of myeloma. The origins of MGUS are likely linked to antigenic stimulation. Studies show that human myeloma cell lines and primary myeloma cells express a broad range of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) which normally help B cells recognize infectious agents and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP).40-42 TLR-specific ligands cause increased myeloma cell proliferation, survival, and resistance to dexamethasone induced apoptosis. In addition, there is overexpression of CD126 (interleukin-6 receptor alpha-chain) in MGUS compared to normal plasma cells.43,44 Thus abnormal TLR expression and/or overexpression of IL-6 receptors in plasma cells may result in an enhanced response to infection and provide a sustained, autocrine IL-6 dependent, proliferative trigger for plasma cells which cause (or act in concert with) the certain cytogenetic events described below to establish the premalignant MGUS stage.

Approximately 50% of MGUS is associated with primary translocations in the clonal plasma cells involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) locus on chromosome 14q32 (IgH translocated MGUS/SMM).1,45 The most common partner chromosome loci and genes dysregulated in these translocations are: 11q13 (CCND1 [cyclin D1 gene]), 4p16.3 (FGFR-3 and MMSET), 6p21 (CCND3 [cyclin D3 gene]), 16q23 (c-maf), and 20q11 (mafB)(Table 2).46-48 Most of the remaining cases of MGUS are associated with hyperdiploidy (IgH non-translocated MGUS).45,49-54

Table 2.

Primary translocations in Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS) and Multiple Myeloma

| Chromosomal translocation | Gene dysregulated by translocation280 |

|---|---|

| t 11;14 | CCND1 (cyclin D1) |

| t 4;14 | FGFR-3 and MMSET |

| t 6;14 | CCND3 (cyclin D3) |

| t 14;16 | C-maf |

| t 14;20 | mafB |

Reproduced with permission from Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA2. Mayo Clinic Proc 2005;80:1371-82. © Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Transformation of MGUS to Myeloma

The progression of MGUS to myeloma represents a simple, random, two-hit genetic model of malignancy.3 Several abnormalities such as Ras mutations, p16 methylation, abnormalities involving the myc family of oncogenes, secondary translocations, and p53 mutations have all been identified in clonal plasma cells in association with progression to the symptomatic stage.46 The bone marrow microenvironment also undergoes marked changes with progression, including induction of angiogenesis,55,56 suppression of cell-mediated immunity,57 and paracrine loops involving cytokines such as interleukin-6 and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor).58

Lytic bone lesions characteristic of myeloma are caused by an imbalance between the activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. There is an increase in RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand) expression by osteoblasts (and possibly plasma cells) accompanied by a reduction in the level of its decoy receptor, osteoprotegerin (OPG).59,60 This leads to an increase in RANKL/OPG ratio, which causes osteoclast activation and bone resorption. In addition, increased levels of macrophage inflammatory protein–1α (MIP-1α), IL-3 and IL-6 produced by marrow stomal cells also contribute to the overactivity of osteoclasts. At the same time, increased levels of IL-3, IL-7 and dickkopf 1 (DKK1) inhibit osteoblast differentiation in myeloma.61

ADVANCES IN DIAGNOSIS

Myeloma is characterized by the presence of monoclonal immunoglobulins in the serum and/or urine. Monoclonal immunoglobulins are commonly referred to as monoclonal proteins, M proteins, or paraproteins. The presence of M proteins is indicative of a clonal plasma cell proliferative disorder such as myeloma, MGUS, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, etc; additional tests are required to distinguish between the various plasma cell disorders. M proteins are detected by serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) in 82% of patients with myeloma, and by serum immunofixation (IFE) in 93%.7 The addition of urine protein electrophoresis and IFE (or the serum free light chain assay) increases the sensitivity of detecting monoclonal proteins in patients with myeloma to 97%.62 Currently only 1-2% of patients with myeloma will have no detectable M on any of these tests; these patients have true non-secretory myeloma.

Protein electrophoresis and immunofixation

Electrophoresis of serum and urine proteins (SPEP and UPEP, respectively) and immunofixation of these samples are the preferred methods of detection of monoclonal (M) proteins. UPEP requires a 24 hour urine collection for accuracy. M proteins on SPEP and UPEP appear as a localized band, and electrophoresis also allows measurement of their size.63 After recognition of a la possible M protein on electrophoresis, immunofixation is necessary for confirmation, and to determine the heavy- and light-chain class of the M protein. In addition, immunofixation is more sensitive than electrophoresis, and allows detection of smaller amounts of M protein and should therefore be performed whenever myeloma, amyloidosis, macroglobulinemia or a related disorder is suspected. Quantitation of serum immunoglobulins is performed with a rate nephelometer in patients in whom serum M proteins are detected as an added parameter that can be followed to assess response. Quantitative immunoglobulins are particularly useful in patients with myeloma and macroglobulinemia where at times the M protein size estimated on SPEP may be unreliable (eg., small beta migrating proteins, and IgA / IgM proteins that tend to polymerize)

Serum free light chain assay

The serum free light-chain (FLC) assay (Freelite™, The Binding Site Limited, Birmingham, U.K.) has been recently introduced into clinical practice.64 This automated nephelometric assay allows quantitation of free kappa (κ) and lambda (λ) chains (i.e., light chains that are not bound to intact immunoglobulin) secreted by plasma cells. An abnormal kappa/lambda FLC ratio indicates an excess of one light chain type versus the other, and is interpreted as a surrogate for clonal expansion based on extensive testing in normal volunteers, and patients with myeloma, amyloidosis and renal dysfunction.64,65 The assay is performed on automated chemistry analyzers, is widely available, and is commonly used to monitor patients with oligo-secretory or non-secretory myeloma and primary amyloidosis, as well as patients with the light-chain only form of myeloma.65-67

The normal serum free-kappa level is 3.3 to 19.4 mg/L and the normal free-lambda level is 5.7 to 26.3 mg/L.68 The normal ratio for FLC-kappa/lambda is 0.26-1.65. The normal reference range in the FLC assay reflects a higher serum level of free lambda light chains than would be expected given the usual kappa/lambda ratio of 2 for intact immunoglobulins. This occurs because the renal excretion of free kappa (which exists usually in a monomeric state) is much faster than free lambda (which is usually in a dimeric state). 64,65 Patients with a kappa/lambda FLC ratio <0.26 are typically defined as having monoclonal lambda free light chain and those with ratios >1.65 are defined as having a monoclonal kappa free light chain. If the FLC ratio is >1.65, kappa is considered to be the “involved” FLC and lambda the “uninvolved” FLC, and vice versa if the ratio is less than 0.26.

In a recent study, 428 patients with a monoclonal gammopathy and urine M protein at initial diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia who had also undergone serum immunofixation and serum FLC quantitation within 30 days of diagnosis were studied.62 The results of SPEP, serum immunofixation, serum FLC, UPEP, and urine immunofixation were then analyzed to determine if all patients could be accurately identified as having a monoclonal plasma cell disorder had the urine studies not been done. All 3 serum studies were normal in only 2 patients (0.5% of the cohort), indicating that urine studies can be eliminated when screening for the presence of monoclonal plasma cell disorders by using the serum FLC assay in combination with the SPEP and immunofixation. However, urine studies are required if a monoclonal process is identified since it helps in monitoring disease progression and response to therapy over time.

Evaluation of bone disease

Plain radiographic examination of all bones including long bones (skeletal survey) is the preferred method of detecting lytic bone lesions in myeloma. CT and MRI scans are more sensitive than conventional radiography in detecting bone disease and are indicated when symptomatic areas show no abnormality on routine radiographs. Fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and bone densitometry studies have shown promise in the evaluation of bone disease in myeloma and need further investigation.

Bone marrow studies

By definition, all patients with myeloma have 10% or more clonal bone marrow plasma cells. If a lower extent of involvement is detected, one is either dealing with an erroneous diagnosis or a sampling error due to patchy marrow involvement. Occasionally an entity called “multiple” solitary plasmacytomas has been described in which there are clearly multiple plasmacytomas on clinical and radiographic examination, but marrow involvement is either minimal or absent. The monoclonal nature of bone marrow plasma cells is established by the demonstration of an abnormal kappa/lambda ratio by immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry. Plasma cells in multiple myeloma typically stain positive for CD38, CD56, and CD138, and are usually negative for surface immunoglobulin and CD19. Bone marrow samples should be studied conventional karyotyping studies and/or fluorescent in-situ hybridization studies to detect specific abnormalities such as t4;14, t14;16, and 17p-.

CURRENT STAGING AND PROGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Staging

Since 1975, the Durie-Salmon staging system has been used to stratify patients with multiple myeloma.69 However, this staging system has limitations especially in the categorization of bone lesions.70,71 Recently Greipp et al, developed an International Staging System (ISS) based on data from 11, 171 patients.72 The ISS overcomes the limitations of the Durie-Salmon staging, and divides patients into 3 distinct stages and prognostic groups based solely on the beta-2-microglobulin and albumin levels in the serum. Table 3 provides the details, and the advantages and disadvantages of these two staging systems.

Table 3.

Staging of Myeloma

| Staging System | Key Stage Characteristics | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Durie-Salmon Staging System | Is more correlated with biologic stage and tumor burden of disease than the international staging system. Disadvantage is complexity, and subjective nature or interpretation of bone findings | |

| Stage I | All of the following:

|

Low M protein defined as IgG <5gm/dL, IgA <3g/dl, urine M spike >4000 mg/24 hours |

| Stage II | Not fitting stage I or II | |

| Stage III | One or more of the following:

|

High M protein defined as IgG >7gm/dL, IgA >5g/dl, urine M spike >12,000 mg/24 hours |

| Subclassification | ||

| A |

|

|

| B |

|

|

| International Staging System | Simple to use, but most renal failure patients will be stage III regardless of tumor burden. Does not apply to monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or smoldering myeloma. | |

| Stage I |

|

|

| Stage II |

|

Prognostic Factors

Once patients are staged, several independent prognostic factors are helpful in predicting outcome in myeloma (Table 4).45,70,73-75 A combination of two or more of the independent prognostic factors listed on Table 4 provides adequate information to estimate prognosis. For example, Facon et al have shown that patients undergoing stem cell transplantation can be grouped into three clear prognostic categories using 2 prognostic factors; median survival was 25 months if patients had a high beta-2 microglobulin and deletion of chromosome 13 by fluorescent in situ hybridization.76 Patients with only one factor abnormal had a median survival of 47 months, while survival was in excess of 111 months in patients in whom both factors were normal.

Table 4.

Major Prognostic Factors in Myeloma

Independent Prognostic Factors

|

Additional Prognostic Factors

|

Prognostic factors such as age, hemoglobin concentration, creatinine, calcium, albumin, immunoglobulin class subtype, and extent of bone marrow involvement have demonstrated some prognostic value.70,73,75 However, they are of limited value once stage and the independent prognostic factors discussed earlier are known.77,78 Newer risk factors such as angiogenesis shed light on biology, but clinical utility is unclear.

Risk-stratification

Using some of the most important clinically available prognostic factors discussed above, a risk-stratification method has been adopted by the Mayo Clinic, called mSMART (Mayo Stratification for Myeloma and Risk-adapted Therapy; www.msmart.org). This model helps stratify patients into high-risk and standard-risk myeloma based on detection of deletion 13 or hypodiploidy on metaphase cytogenetic studies, deletion 17p- or immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) translocations t(4;14) or t(14;16) on molecular genetic studies, or plasma cell labeling index of 3% or higher on bone marrow immunofluorescent studies. Presence of any one or more of these high-risk factors (Table 5) classifies a patient as having high-risk MM.79 The median survival of high-risk MM is only 2-3 years even with tandem stem cell transplantation, compared to over 6-7 years in patients with average-risk MM.2

Table 5.

Mayo Risk-Stratification for Myeloma271

| High-risk characteristic | Percentage of newly diagnosed patients with the abnormality 7,45,281 |

|---|---|

| Conventional Cytogenetics: | |

| Deletion of chromosome 13 (monosomy) | 14% |

| Hypodiploidy | 9% |

| Either hypodiploidy or deletion 13 | 17% |

| Fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH): | |

| t(4;14) | 15% |

| t(14:16) | 5% |

| 17p- | 10% |

| Plasma cell labeling index (PCLI) studies: PCLI ≥3% | 6% |

| Any one of the above high-risk abnormalities | 25-30% |

Reproduced with permission from Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA2. Mayo Clinic Proc 2005;80:1371-82. © Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

RESPONSE ASSESSMENT

Several criteria have been used over the years to assess response to therapy in myeloma. In recent years, the European Group for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant/ International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry/ American Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (EBMT/ IBMTR/ ABMTR criteria for the response and progression of MM treated by stem cell transplantation, commonly referred to as the Blade criteria or the EBMT criteria was adopted in many trials.80 Other commonly used response criteria were those developed by the Chronic Leukemia-Myeloma Task Force, Southwest Oncology group (SWOG), and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) have been largely abandoned. In 2006, the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) recognized the need for uniformity and published uniform response criteria that are to be used in future clinical trials.81

The IMWG uniform response criteria are similar to the EBMT criteria with a few major exceptions: addition of free light chain response and progression criteria for patients without measurable disease (see Table 6 for definition of measurable disease), modification of the definition for disease progression for patients in complete response, addition of very good partial response and stringent response categories, elimination of the minor response category, elimination of the mandatory 6 week wait time to confirm response, and some additional clarifications and correction of errors. The IMWG criteria for response and progression are listed on Table 7.

Table 6.

Definition of Measurable Disease

One or more of the following:

|

The FLC assay is not to be used for response assessment in patients who have evidence of measurable disease in the serum or urine by M protein levels.

Table 7.

International Myeloma Working Group Uniform Response criteria for multiple myeloma 81

| Response subcategory | Response criteria |

|---|---|

| Complete response* (CR) |

|

| Stringent complete response (sCR) | CR as defined above plus

|

| Very good partial response (VGPR)* |

|

| Partial Response (PR) |

|

| Stable disease (SD) |

|

| Progressive Disease (PD)* | Increase of 25% from lowest response value in any one or more of the following:

|

All response categories (CR, sCR, VGPR, PR) require two consecutive assessments made at anytime before the institution of any new therapy; complete and PR and SD categories also require no known evidence of progressive or new bone lesions if radiographic studies were performed. Radiographic studies are not required to satisfy these response requirements. Bone marrow assessments need not be confirmed.

Note clarification to IMWG criteria for coding CR and VGPR in patients in whom the only measurable disease is by serum FLC levels: CR in such patients a normal FLC ratio of 0.26-1.65 in addition to CR criteria listed above. VGPR in such patients is defined as a >90% decrease in the difference between involved and uninvolved free light chain FLC levels.

Adapted with permission from Durie et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2006;20:1467-73 81

NEW AGENTS IN THE TREATMENT OF MYELOMA

As described earlier, for decades, the mainstay of therapy has been alkylators and corticosteroids, specifically the oral regimen of melphalan and prednisone (MP). High dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) was subsequently shown to prolong survival compared to conventional chemotherapy, and adopted into standard practice. More recently, thalidomide,82 bortezomib,83,84 and lenalidomide,85,86 have emerged as effective agents in the treatment of myeloma (Table 8), and each has an interesting historical perspective.

Table 8.

New drugs with significant single-agent activity in multiple myeloma

| Agent | Usual Starting Dose | Postulated Mechanism of Action | Side-effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thalidomide | 50-200 mg orally days 1-28 every 4 weeks | Anti-angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Direct cytotoxicity by inducing free radical mediated DNA damage. | Sedation, fatigue, skin rash, bradycardia, peripheral neuropathy and constipation are the most common side effects. Deep vein thrombosis when combined with dexamethasone or chemotherapy. Less frequent but serious side-effects are seizures, cardiac arrhythmia, and Stevens Johnson syndrome. |

| Bortezomib | 1.3mg/m2 intravenously days 1, 4, 8, 11 every 21 days | Inhibits the ubiquitin-proteasome catalytic pathway in cells by binding directly with the 20S proteasome complex. | The most common toxicities are gastrointestinal, transient cytopenias, fatigue, and peripheral neuropathy. |

| Lenalidomide* | 25 mg orally days 1-21 every 28 days | Analog of thalidomide. Immunomodulation and anti-angiogenesis | The most common adverse effects are grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. |

Reproduced with permission from Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA2. Mayo Clinic Proc 2005;80:1371-82. © Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

In this section, the new agents for the treatment of myeloma will be reviewed. Subsequent sections will discuss in detail the current approach to initial therapy, stem cell transplantation, maintenance therapy, and treatment of relapsed refractory disease.

Thalidomide

Historical perspective

Chemie Grünenthal, a German pharmaceutical company introduced thalidomide(α-N-[phthalimido] glutarimide) into the market as a sedative on October 1, 1957.87-89 By 1960, it was sold in over 40 countries, and became popular both as a sedative and as treatment for morning sickness of pregnancy. It was marketed under various commercial names such as ‘Contergan’, ‘Distaral’, ‘Softenon’, ‘Neurosedyn’, ‘Isomin’, ‘Kedavon’, ‘Telargan’, and ‘Sedalis.’90

On November 18, 1961, Widukind Lenz, a German physician and geneticist determined that thalidomide was associated with severe teratogenic malformations.90 In December 1961, independent confirmation came from William McBride, an Australian obstetrician.91 Fetal malformations occurred inevitably when the drug was taken in the first trimester between days 35-49 after the last menstrual period.87,88 By the end of 1961, thalidomide was taken off the market in most countries but almost 10,000 infants had already been affected. The United States was spared, because the drug had been denied approval by Dr. Frances Kelsey at the FDA who was concerned about the lack of safety data.92

Shortly after the teratogenic properties of thalidomide were known, it was considered as a possible treatment against cancer.93,94 At least three clinical trials were undertaken in cancer,95,96 but no significant activity was seen. Although thalidomide was taken off the market and was unsuccessful against cancer, it nevertheless persisted as a therapeutic agent due to promising activity detected in leprosy (1964),97,98 Behcet’s Disease (1979),99 graft versus host disease (1988),100-104 and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated oral ulcers105 and wasting (1989).106 Under pressure from HIV activists and to discourage illegal drug distribution networks, the FDA approved thalidomide for the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum in the United States in July 1998 with a built in safety system termed the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS) program.107,108

Thalidomide is a chiral molecule and is dispensed as a racemic mixture of the (R)- (dextrorotatory) and (S)- (levorotatory) enantiomers.109,110 Although it is felt that the (R)- enantiomer is responsible for most of its sedative activities, and the (S)- enantiomer has a significant role in the teratogenic and anti-tumor properties, differences in enantio-selectivity are not clinically relevant because of rapid chiral interconversion in vivo at physiologic pH.111 As a result of this rapid racemization, the use of a pure (R)- enantiomer therefore would not have prevented the thalidomide tragedy. Most of the metabolism is by non-enzymatic hydrolysis, and no major dose reductions are generally needed in liver or renal failure.

Initial results in myeloma

Based on the significant anti-angiogenic properties of thalidomide,112,113 and evidence of increased angiogenesis in myeloma, Singhal, Barlogie and colleagues treated patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma with the drug in late 1997. Thirty-two percent of 84 patients responded, making thalidomide the first new drug with single-agent activity for myeloma in over three decades.82,114 These results were confirmed by many other centers, in all phases of the disease.115-122

Studies show that response rates in relapsed disease are about 50% with the combination of thalidomide and steroids,123 and increase to over 65% with an oral three-drug combination of thalidomide, steroids and cyclophosphamide (CTD).124-126 Several other combination chemotherapy regimens containing thalidomide have been developed including DT-PACE (dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide and etoposide), BLT-D (clarithromycin, low dose thalidomide, and dexamethasone), and MTD (melphalan, thalidomide and dexamethasone).127

Dosage

Initially thalidomide was used in doses of up to 800 mg per day. However, most side-effects of thalidomide are dose-dependent, and there is no major improvement in clinical activity beyond a dose of 200 mg. Currently, thalidomide is usually given in a dosage of 50 to 200 mg daily; the dose is typically adjusted to the lowest dose that can achieve and maintain a response in order to minimize long-term toxicity. In most elderly patients (age >65) a dose of 50 to 100 mg is better tolerated.

Side-effects

The known toxicities of thalidomide include peripheral neuropathy, constipation, fatigue and sedation.128 Therapy for myeloma has revealed new toxicities of thalidomide that were previously unrecognized. These include deep vein thrombosis,129-132 toxic epidermal necrolysis,133 and hypothyroidism.134 The incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is only 1-3% in patients receiving thalidomide alone, but rises to approximately 10-15% in patients receiving thalidomide in combination with dexamethasone, and to about 25% in patients receiving the agent in combination with other cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents, particularly doxorubicin.129-131,135,136 The management of thalidomide toxicity has been reviewed in detail by Ghobrial et al.128

Bortezomib

Historical Perspective

The multi-catalytic ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is responsible for the degradation of eukaryotic cellular proteins.137-140 The orderly degradation of cellular proteins by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is critical for signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, response to stress, and control of receptor function.141-144 The 26S proteasome (1500-2000 kDa) consists of a core 20S catalytic complex (approximately 700 kDa) and a 19S regulatory complex (Figure 1).137,141,144-148 Ubiquitin tagged proteins are recognized by the 19S regulatory complex, where the ubiquitin tags are removed proteins are fed into the inner catalytic compartments of the 20S proteasome cylinder for hydrolysis into small polypeptides ranging from 3 to 22 amino acids in length.149,150 151 152 137,150,153

Figure 1.

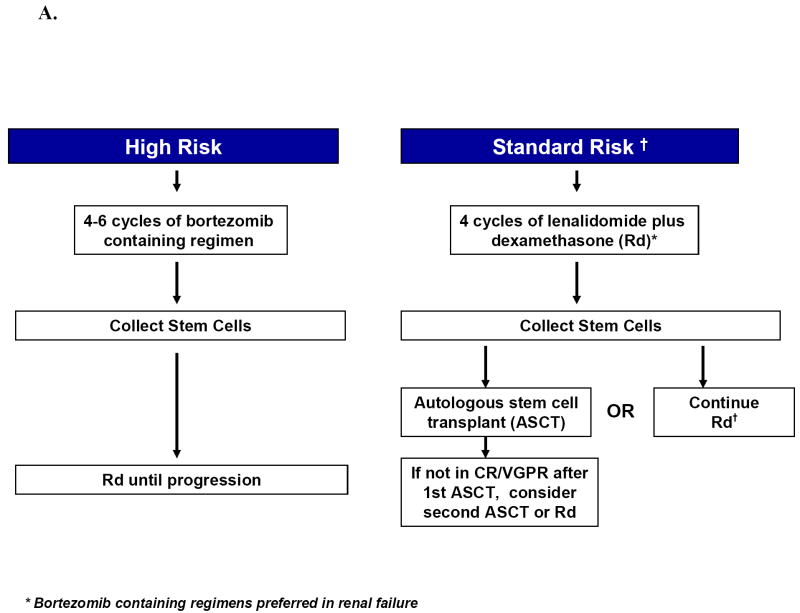

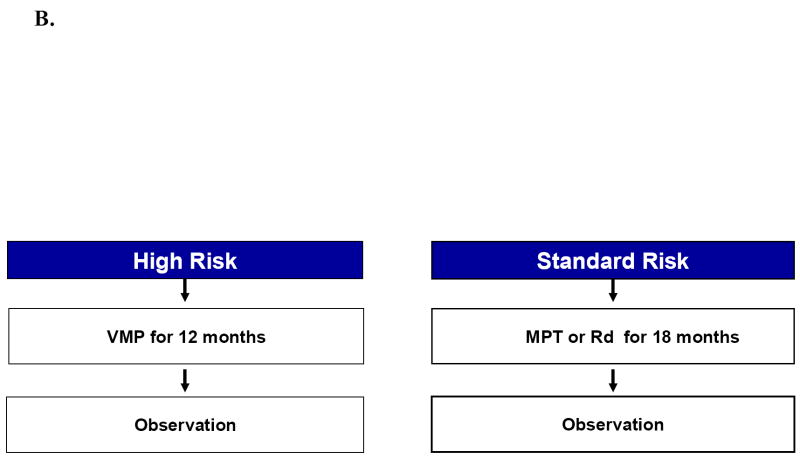

Approach to the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma in patients who are candidates for transplant (A) and those who are not candidates for transplant (B). Footnote for Figure 1A. Rd, lenalidomide plus low dose dexamethasone; CR, complete response; VGPR, very good partial response; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation Footnote for Figure 1B. MPT, melphalan, prednisone, thalidomide; VMP, bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone.

Inhibition of the proteasome inhibition leads to cellular apoptosis, with malignant, transformed and proliferating cells being more succeptible.148,154 137,155-158 Numerous proteasome inhibitors were developed but none was suitable for clinical use.141,148,159,160 Subsequently, Adams and colleagues designed and developed several boronic acid derived compounds that inhibit the proteasome pathway in a highly specific manner.154 Bortezomib (N-pyrazinecarbonyl-l-phenylalanine-l-leucine boronic acid; previously known as PS-341 or MLN-341), a boronic acid dipeptide was then selected for preclinical and clinical testing.83,154 Bortezomib inhibits the proteasome pathway rapidly and in a reversible manner by binding directly with the 20S proteasome complex and blocking its enzymatic activity.

Preclinical studies demonstrated that bortezomib had potent cytotoxic and growth inhibitory effects across the panel of 60 cell lines from the NCI and in several murine models.139,161-166 Bortezomib also showed striking activity against myeloma cells in several preclinical models.167 168-170 Orlowski and colleagues conducted a phase 1 study in which responses were seen in several myeloma patients.

Initial results in myeloma

In the first phase II trial conducted in 202 patients with relapsed/refractory MM, approximately one-third responded to bortezomib therapy, with an average response duration of one year.83 These results were confirmed in a randomized phase II trial in patients who failed to respond or relapsed after front-line therapy for myeloma.171 Although initial trials only allowed a maximum of 8 cycles of bortezomib, responding patients were allowed to receive continued treatment on a compassionate use protocol, data from which indicate that it is safe to give at least an additional 5-6 cycles of therapy, without undue toxicity.171 In a recent randomized trial, progression free survival was superior with bortezomib compared to dexamethasone alone in patients with relapsed, refractory myeloma.84

Dosing

The starting dose of bortezomib is 1.3 mg/m2 given twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every 21 days. Dosage may need to be decreased to 1.0 mg/m2 or 0.7 mg/m2 based on toxicity. Although no clear maintenance dose has been defined, after 4-6 cycles, the dosage often needs to be decreased if there is a necessity to continue the drug in order to minimize the risk of neuropathy. One strategy is to lengthen the cycle length from 21 days to 28 or even 35 days. Another option is to administer bortezomib once a week.

Side-effects

The most common toxicities attributable to bortezomib therapy are gastrointestinal side effects, cytopenias, fatigue, fever, and peripheral neuropathy Peripheral neuropathy occurs in approximately 45% of patients, and is the most worrisome adverse effect. It can be painful. It is more frequent in patients who have received prior neurotoxic therapy and in those with pre-existing neuropathy. Neuropathy can be of grade 3 severity in about 10% of patients receiving therapy. Postural hypotension occurs in approximately 10% of patients.

Lenalidomide

Historical Perspective

Shortly after thalidomide was determined to be a teratogen in the 1960s, a number of analogs of thalidomide were synthesized to determine the mechanism of its teratogenicity. Similarly in the 1990s, a number of thalidomide analogs were synthesized in an attempt to increase efficacy and minimize toxicity. Lenalidomide, a 4-amino substituted analog of thalidomide formerly called CC-5013, is in a class of thalidomide analogs termed immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs). It is safer and more effective than thalidomide in preclinical and clinical studies. In contrast to the clinical development of thalidomide, the development of lenalidomide can be considered an inevitable occurrence, commonly seen in various fields of medicine where pharmaceutical companies develop closely related and presumably more effective alternatives once an effective parent drug is identified.

Based on the preclinical studies conducted by the manufacturer and at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, lenalidomide was tested in phase I trials in relapsed refractory myeloma.172

Initial Results in myeloma

Lenalidomide first showed promising activity in MM in 2 phase I trials.172,173 In a phase II trial conducted at Mayo Clinic, 31 of 34 patients (91%) with newly diagnosed myeloma achieved an objective response with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone.85 Richardson et al reported on single-agent activity in a multi-center randomized phase II trial that enrolled 102 patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma.86 Overall response rate with single-agent lenalidomide was 17%. Two large phase III trials demonstrated significantly superior time to progression and overall survival with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone compared to placebo plus dexamethasone in relapsed myeloma.174,175 Based on these two randomized trials, lenalidomide plus dexamethasone was approved by the FDA in June 2006 for the treatment of myeloma in patients who have failed one prior therapy.

Dosing

Typical dosing of lenalidomide for myeloma is 25 mg per day on days 1-21 of a 28 day cycle, with dose adjustments based on toxicity. With prolonged therapy dose adjustments are usually needed. Most patients who receive lenalidomide for over one year are usually on lower doses of 5-15 mg per day given in the usual schedule. The dosing of lenalidomide in renal failure is unclear, and caution must be exercised since the drug is renally excreted.

Side-effects

The most common side-effects of lenalidomide are cytopenias. Fatigue, dryness of skin, and rash are other common side effects. The incidence of DVT is low (2-3%) with single-agent lenalidomide or lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone, but rises markedly when the agent is combined with high-dose dexamethasone (approximately 20%). The risk of DVT can be decreased to less than 10% by reducing the dose of dexamethasone to 40 mg once a week.

Liposomal-doxorubicin

For many years, doxorubicin has been used in myeloma as part of the VAD regimen and other combination regimens. However, the single-agent activity of doxorubicin is minimal. Recently, liposomal doxorubicin has shown activity in newly diagnosed and relapsed myeloma. In a randomized trial, bortezomib plus liposomal doxorubicin was associated with a superior time to progression, resulting in the approval of liposomal doxorubicin for the treatment of relapsed myeloma.176 Further studies are needed to define the role of liposomal doxorubicin in myeloma.

Pomalidomide (CC-4047)

Pomalidomide (an analog of thalidomide and lenalidomide) has shown promising single-agent activity.177 In combination with low-dose dexamethasone pomalidomide has shown a response rate of over 60% in relapsed myeloma in a trial conducted by the Mayo Clinic.178 In this trial, pomalidomide was given orally 2 mg daily on days 1-28 of a 28-day cycle. Dexamethasone was given orally at a dose of 40 mg daily on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 of each cycle. Additional studies are ongoing. Pomalidomide is not approved by the FDA.

Carfilzomib

Carfilzomib, an irreversible proteasome inhibitor has shown significant single-agent activity in myeloma in two separate trials.179,180 The dose of carfilzomib was 20 mg/m2 intravenously days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15 and 16 every 28 days, for up to 12 cycles. There is a suggestion that carfilzomib may have less neurotoxicity compared with bortezomib. It is also not approved by the FDA so far. Clinical trials with carfilzomib are ongoing.

Other new drugs

There is a continued search for other active agents based on advances in myeloma biology.181 Other agents which have raised some interest and are undergoing testing include heat shock protein inhibitors, histone deacetylase inhibitors, perifosine, and bendamustine.

INITIAL TREATMENT OF MYELOMA

The median survival of symptomatic myeloma is 4 years. For over 3 decades, the mainstay of therapy was oral chemotherapy with melphalan and prednisone (MP). High dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) prolongs survival compared to conventional chemotherapy, and is now routinely incorporated into the treatment strategy either early in the disease course or at the time of relapse in eligible patients. As discussed earlier, thalidomide,82 bortezomib,83,84 and lenalidomide,85,86 have emerged as effective agents in the treatment of myeloma and have greatly altered the way myeloma is treated today.

Despite many advances, there is still no evidence that early treatment of patients with asymptomatic (smoldering) multiple myeloma prolongs survival compared to therapy at the time of symptoms. Similarly the use of bisphosphonates does not alter the natural history of smoldering myeloma, and are not indicated.182 Therapy is therefore initiated only in patients defined as having multiple myeloma based on the criteria listed on Table 1; patients with smoldering myeloma should be observed closely without treatment. In all stages of myeloma, clinical trials are preferred over standard therapeutic approaches, since the disease is still incurable. Over the years several landmark trials have greatly altered the treatment of myeloma, details of which are listed on Table 9.

Table 9.

Results Of Selected Randomized Trials That Have Had A Major Impact On Myeloma Therapy

| Trial | Disease Stage | Treatment comparison |

Total Number of patients studied |

CR/VGPR (%) |

Median EFS (months) |

Median OS (months) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Transplantation | |||||||

| IFM 90206 | Newly Diagnosed | Conv. chemo | 100 | 13 | 18 | 44 | Established role of ASCT |

| ASCT | 100 | 38 | 28 | 57 | |||

| MRC VII207 | Newly Diagnosed | Conv. chemo | 201 | 8 | 20 | 42 | Confirmed role of ASCT |

| ASCT | 200 | 44 | 32 | 54 | |||

| MAG 90213 | Newly Diagnosed | Delayed ASCT | 94 | 21 | 13 | 65 | Demonstrated delayed ASCT as an alternative |

| Early ASCT | 91 | 32 | 39 | 64 | |||

| United States Intergroup S9321282 | Newly Diagnosed | Delayed ASCT | 255 | 15* | 21 | 64 | Demonstrated delayed ASCT as an alternative; dampened enthusiasm for allogeneic SCT |

| Early ASCT | 261 | 17* | 25 | 58 | |||

| Allogeneic SCT | 36 | 17* | NR | 6 | |||

| IFM 94283 | Newly diagnosed | Single ASCT | 199 | 42 | 25 | 48 | Established role of tandem ASCT if CR/VGPR not achieved with first ASCT |

| Double ASCT | 200 | 50 | 30 | 58 | |||

| PETHEMA284 | Post-induction (responding patients only) | Conv. chemo | 83 | 11* | 33 | 66 | Demonstrated that ASCT may have limited value in patients responding well to induction |

| ASCT | 81 | 30* | 42 | 61 | |||

| Italian232 | Newly diagnosed | Tandem ASCT | 82 | N/A | 29 | 54 | Demonstrated efficacy of single ASCT followed by non- myeloablative SCT in selected patients |

| Single ASCT followed by non-myeloablative SCT | 80 | N/A | 35 | 80 | |||

| New therapies | |||||||

| Italian GIMEMA group197 | Newly diagnosed | MP | 126 | 12 | 27 | 64% at 3yrs | Demonstrated potential value of MPT over the classic MP regimen |

| MPT | 129 | 36 | 54 | 80% at 3yrs | |||

| IFM 99-06199 | Newly diagnosed | MP | 196 | 7 | 18 | 33 | Changed standard of care in elderly to MPT (after 3 decades of MP) |

| MPT | 125 | 47 | 28 | 52 | |||

| Tandem intermediate-dose ASCT | 126 | 43 | 19 | 38 | |||

| APEX84 | Relapsed, refractory (1-3 prior therapies) | Bortezomib | 333 | 13 | 6** | NR | Led to full approval of bortezomib in the US |

| Dex | 336 | 2 | 3** | NR | |||

| MM-010174 | Relapsed, refractory (1-3 prior therapies) | Len/ Dex | 351 | 15* | 11** | Not reached | Pivotal trial establishing role of lenalidomide |

| Placebo/Dex | 3* | 5** | |||||

| MM-009175 | Relapsed, refractory (1-3 prior therapies) | Len/ Dex | 341 | 13* | 11* | 30 | Led to approval of lenalidomide in the US |

| Placebo/Dex | 1* | 5* | 20 | ||||

Abbreviations: ASCT, autologous hematopoetic stem cell transplantation; Conv. chemo, conventional chemotherapy; CR, complete response; Dex, dexamethasone; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EFS, event free survival; GIMEMA, Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto; IFM, InterGroupe Francophone du Myélome; Len, Lenalidomide; MAG, Myélome Autogreffe; MM, multiple myeloma; MP, melphalan plus prednisone; MPT, melphalan, prednisone, thalidomide; MRC, Medical Research Council; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival; PETHEMA, Programa para el Estudio y Tratamiento de las Hemopatias Malignas; PFS, progression free survival; SCT, stem cell transplantation; US, United States; VGPR, very good partial response.

Denotes CR only; VGPR not reported.

PFS data not available; numbers reflect median time to progression

This Table was originally published in Blood. Kyle RA and Rajkumar SV. Multiple Myeloma. Blood. 2008; 111;2962-2972. © the American Society of Hematology

The choice of initial therapy depends on eligibility for stem cell transplantation and risk-stratification. The overall approach to treatment of symptomatic newly diagnosed multiple myeloma is outlined in Figure 1A and B. Eligibility for stem cell transplantation is determined by age, performance status, and coexisting comorbidities. Risk-Stratification is based on presence or absence of high-risk factors (Table 5)79 Table 10 lists the most common regimens used in the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma, including recommended doses and activity.

Table 10.

Dosing Schedule and Response Rates of Commonly used Chemotherapy Regimens in Myeloma

| Regimen | Suggested Dosing Schedule* | Response rate in newly diagnosed myeloma | CR+VGPR‡ rate in newly diagnosed myeloma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transplant Candidates | |||

| Thalidomide- Dexamethasone** (Thal/Dex)185,188 | Thalidomide 100-200mg oral days 1-28 | 63% | 44% |

| Dexamethasone 40mg oral days 1, 8, 15, 22 every 28 days | |||

| Repeated every 4 weeks × 4 cycles as pre-transplant induction therapy; or continued for up to one year or progression if used as primary therapy | |||

| Lenalidomide-Dexamethasone (Rev/low-dose Dex)285 | Lenalidomide 25mg oral days 1-21 every 28 days | 71% | 42% |

| Dexamethasone 40mg oral days 1, 8, 15, 22 every 28 days | |||

| Repeated every 4 weeks × 2-4 cycles as pre-transplant induction therapy; or continued till progression if used as primary therapy | |||

| Bortezomib-Dex (Vel/Dex)286 | Bortezomib 1.3mg/m2 intravenous days 1, 4, 8, 11 | 80% | 47% |

| Dexamethasone 40mg oral days 1-4, 9-12 | |||

| Reduce dexamethasone to days 1-4 only after first 2 cycles | |||

| Repeated every 3 weeks × 2-4 cycles as pre-transplant induction therapy | |||

| Bortezomib-Thalidomide-Dexamethasone (VTD)**287 | Bortezomib 1.3mg/m2 intravenous days 1, 4, 8, 11 | 93% | 60% |

| Thalidomide 200mg oral days 1-21 | |||

| Dexamethasone 20 mg day of and day after bortezomib | |||

| Repeated every 3 weeks × 3 cycles as pre-transplant induction therapy | |||

| VDT-PACE‡196 | Dexamethasone 40 mg/day PO daily days 1-4 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Thalidomide 100 mg/day days 1-28† | |||

| Cisplatin 10 mg/m²/day intravenous infusion over 24 hours days 1-4 | |||

| Cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m²/day intravenous infusion over 24 hours days 1-4 | |||

| Etoposide 40 mg/m²/day intravenous infusion over 24 hours days 1-4 | |||

| Doxorubicin 10 mg/m²/day intravenous infusion over 24 hours days 1-4 | |||

| Bortezomib 1 mg/m²/day intravenous on days 1,4,8,11 | |||

Note:

|

|||

| Non-Transplant Candidates | |||

| Melphalan-Prednisone | Melphalan 9mg/m2 oral days 1-4 | 35 | 8% |

| Prednisone 60mg/m2 oral days 1-4 | |||

| Repeated every 6 weeks until plateau | |||

| An alternative schedule is melphalan 8-10 mg oral days 1-7 with prednisone 60 mg days 1-7 repeated every 6 weeks until plateau | |||

| Melphalan-Prednisone- Thalidomide (MPT)199† | Melphalan 0.25mg/kg oral days 1-4 | 76% | 47% |

| Prednisone 2mg/kg oral days 1-4 | |||

| Thalidomide 100-200mg oral days 1-28 | |||

| Repeated every 6 weeks × 12 cycles | |||

| Borteozmib-Melphalan-Prednisone (VMP)204 | Melphalan 9 mg/m2 oral days 1-4 | 71% | 41% |

| Prednisone 60 mg/m2 oral days 1 to 4 | |||

| Bortezomib 1.3mg/m2 intravenous days 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29, 32 | |||

| Repeated every 42 days × 4 cycles followed by maintenance therapy as given below: | |||

| Melphalan 9 mg/m2 oral days 1-4 | |||

| Prednisone 60 mg/m2 oral days 1 to 4 | |||

| Bortezomib 1.3mg/m2 intravenous days 1, 8, 15, 22 | |||

| Repeated every 35 days × 5 cycles | |||

Starting and subsequent doses need to be adjusted for performance status, renal function, blood counts, and other toxicities;

Dexamethasone dose listed is lower than used in trial.

Thalidomide dose listed is lower than used in trial

CR, complete response; VGPR, very good partial response; VDT-PACE, velcade, dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin (platinum), Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide.

Transplant-Candidates

It is important to avoid protracted melphalan-based therapy in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma who are considered eligible for ASCT, since it can interfere with adequate stem cell mobilization, regardless of whether an early or delayed transplant is contemplated. Typically patients are treated with approximately 4 cycles of induction therapy prior to stem cell harvest. This includes patients who are transplant candidates but who wish to reserve ASCT as a delayed option for relapsed refractory disease. Such patients can resume induction therapy following stem cell collection until a plateau phase is reached, reserving ASCT for relapse.

Vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone (VAD)

VAD was used for many years as pre-transplant induction therapy for patients considered candidates for ASCT. However, VAD requires an intravenous indwelling catheter, which predisposes patients to catheter related sepsis and thrombosis. Moreover, the neurotoxicity of vincristine can limit the future use of thalidomide and bortezomib, both of which also have neurotoxic potential. Most of the activity of VAD is from the high-dose dexamethasone component. Recently, Cavo and colleagues in a matched case-control study of 200 patients demonstrated that response rates with VAD were significantly lower compared to Thal/Dex; 76% versus 52%, respectively.183 Preliminary results from a randomized trial from France confirm these findings.184 As a result, VAD is not recommended anymore as initial therapy.

Pulsed Dexamethasone

Dexamethasone alone has also been used as induction therapy. It is typically used at a dose of 40 mg orally on days 1-4, 9-12, and 17-20 every 4-5 weeks. Objective response rates are approximately 45%,185 significantly lower compared to newer induction regimens. In randomized trials the early mortality rate associated with dexamethasone is over 10% in the first 4 months of therapy, reflecting the toxicity and ineffectiveness of this regimen. Consequently, single-agent dexamethasone is also no longer recommended as initial therapy.

Thalidomide-Dexamethasone (Thal/Dex)

In the last few years, Thal/Dex has emerged as the most commonly used induction regimen for the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma in the United States. The use of Thal/Dex was initially based on three phase II clinical trials.118,186,187 Response rates with Thal/Dex range 64-76% in these studies, comparable or better than those obtained with infusional VAD.

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) recently reported the results of a randomized trial comparing Thal/Dex to dexamethasone (Table 7).185 Two hundred seven patients were studied. The best response within four cycles of therapy was significantly higher with Thal/Dex compared to dexamethasone alone; 63% versus 41%, respectively, P=0.0017. Adjusted response rates allowing for the use of serum M protein values alone in patients in whom a measurable urine protein at baseline was unavailable at follow-up were 72% with Thal/Dex versus 50% with dexamethasone alone. Stem cell harvest was successful in 90% of patients in each arm. DVT was more frequent with Thal/Dex (17% versus 3%). Overall, grade 3 or higher non-hematologic toxicities were seen in 67% of patients within four cycles with Thal/Dex and 43% with dexamethasone alone (P <0.001). Early mortality (first 4 months) was 7% with Thal/Dex and 11% with dexamethasone alone. Based on this trial, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted accelerated approval for Thal/Dex for the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma.

Confirmatory results are available from a separate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing Thal/Dex versus placebo/dexamethasone (Placebo/Dex) as primary therapy in 470 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.188 In this trial, the overall response rate was significantly higher with Thal/Dex compared with Placebo/Dex (63% v 46%), P < 0.001. Time to progression (TTP) was significantly longer with Thal/Dex compared with Placebo/Dex (median, 22.6 v 6.5 months, P < 0.001). As in the ECOG study, grade 4 adverse events were more frequent with Thal/Dex than with Placebo/Dex (30.3% v 22.8%).

A Dutch study compared thalidomide, Adriamycin, dexamethasone (TAD) with VAD as induction therapy.189 After induction patients in both arms proceeded to stem cell transplantation. A total of 556 patients were randomized and progression free survival was superior with TAD compared with VAD, median 25 months to 33 months (P<0.001). However no difference in overall survival was seen.

Patients receiving thalidomide in combination with high-dose steroids or chemotherapy need routine thromboprophylaxis with coumadin (target INR 2-3) or low-molecular weight heparin (equivalent of enoxaparin 40mg once daily). Aspirin can be used instead in patients receiving only low doses of dexamethasone (40mg once a week or lower) or prednisone in combination with thalidomide, provided no concomitant erythropoietic agents are used.

Lenalidomide-dexamethasone (Rev/Dex)

In a phase II trial conducted at the Mayo Clinic demonstrated remarkably high activity with the Rev/Dex regimen. Thirty-one of 34 patients (91%) achieved an objective response, including 2 (6%) achieving complete response (CR), and 11 (32%) meeting criteria for very good partial response (VGPR).85 Lacy et al recently updated the results of this study. With longer follow-up, 56% of patients achieved very good partial response or better. In the subset of 21 patients receiving Rev/Dex as primary therapy without ASCT, 67% achieved VGPR or better.190 Approximately fifty percent of patients experienced grade 3 or higher non-hematologic toxicity, similar to rates seen with dexamethasone alone.

ECOG recently reported preliminary findings of a randomized trial testing Rev/Dex as administered in the Mayo Phase II trial (and in the regulatory relapsed refractory myeloma studies) versus Rev/low-dose Dex (40 mg dexamethasone once weekly).191 Results so far show that toxicity rates are significantly higher with Rev/standard-dose Dex compared to Rev/low-dose Dex. Early (first 4 month) mortality rates were low in both arms, 5% and 0.5% respectively. The early mortality rate in the Rev/low-dose dexamethasone arm is probably the lowest reported in any large phase III newly diagnosed trial in which enrollment was not restricted by age or eligibility for stem cell transplantation; DVT rates are also low, making this one of the safest pre-transplant induction regimens for myeloma. Based on this Rev/low-dose dexamethasone is currently the regimen of choice in the Mayo Stratification for Myeloma and Risk-adapted Therapy (mSMART) protocol for the treatment of standard-risk myeloma in patients who are candidates for ASCT outside the setting of a clinical trial.79

Recommendations for thromboprophylaxis are similar to those discussed above with Thal/Dex; aspirin alone is probably sufficient for patients receiving lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone.

Bortezomib-based regimens

In newly diagnosed myeloma, bortezomib has shown response rates of approximately 40% as a single-agent. 192 Significantly higher response rates (approximately 70-90%) have been observed with bortezomib plus dexamethasone (Vel/Dex),193,194 bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone (VTD) and other bortezomib-based combinations. The CR plus VGPR rate is approximately 25-30% with Vel/Dex in one study. No adverse effect on stem cell mobilization was noted.

Harousseau and colleagues recently reported preliminary results of a randomized trial comparing VAD versus Vel/Dex as pre-transplant induction therapy.195 With over 400 patients enrolled, preliminary results show superior response rates and long-term outcome with Vel/Dex compared to VAD. DVT risk was low with bortezomib (<5%).

Bortezomib-based regimens are of particular value in patients with renal failure and in patients with high-risk myeloma (see below), and is not associated with high rates of thrombosis.

Other induction regimens

The role of other pre-transplant induction regimens, such as those containing doxorubicin or liposomal doxorubicin, need to be weighed in terms of the added side-effects that can affect quality of life, and should be considered investigational until future studies show that the addition of these agents improves long-term outcome compared to the regimens discussed above. One exception is patients presenting with very aggressive disease including plasma cell leukemia features or rapidly progressive disease with or without extramedullary features. In these patients, 2 cycles of the combination chemotherapy regimen VDT-PACE (bortezomib (Velcade), dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin (platinum), doxorubicin (Adriamycin), cyclophosphamide, and etoposide) developed by Barlogie et al as part of total therapy III is highly effective in controlling the disease rapidly.196

Initial Therapy in Standard-Risk Patients Eligible for Transplantation

Patients who are not transplant candidates are treated with standard alkylating agent therapy. For decades this has meant therapy with melphalan plus prednisone (MP).1 Over the years, despite better response rates, no survival benefit has been reported with any of the more aggressive combination chemotherapy regimens compared to MP. Two recent randomized studies show that MPT (melphalan, prednisone, thalidomide) improves response and EFS compared to MP;197,198 an overall survival advantage has been observed in one of the two trials.198 As a result, MPT has emerged as the current standard of care for patients not eligible for ASCT.

Melphalan, prednisone (MP)

MP has been used for decades in myeloma. The use of MP has decreased due to more active regimens as discussed below. However, it is still a regimen of value in frail, elderly patients who may not tolerate bortezomib or thalidomide well. The response rate with MP is approximately 50%, and complete responses occur in fewer than 5% of patients. Prior to the arrival of new agents such as thalidomide and bortezomib, despite better response rates no survival benefit was found with any combination chemotherapy regimen compared to MP.35 The dosing of MP is given on Table 10.122 Blood counts are monitored 3 weeks after beginning therapy and the dose of melphalan is adjusted to produce mild cytopenia at mid-cycle.

Melphalan, prednisone, thalidomide (MPT)

Five randomized trials have compared MP to MPT.197,199-202 Only two show a clear overall survival benefit.199,200

Facon et al199 randomized 447 patients (ages 65-75) to MP versus MPT versus tandem autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) with reduced dose melphalan (Melphlan100 mg/m2) (Table 9). Early (first 3 months) mortality rate was 8% with MP compared to 3% with MPT. Significantly higher response and PFS rates were observed with MPT compared with either MP or tandem ASCT groups. More importantly the trial demonstrated a significant survival advantage with MPT; median overall survival not reached at 52 months, 33 months, and 38 months, respectively (p<0.001).

Hulin et al200 confirmed a survival advantage with MPT compared with MP in a randomized trial in patients over the age of 75. After numerous attempts to improve on MP over the years with a variety of combination chemotherapy regimes, the results of these 3 randomized trials finally changed the standard of care for elderly patients.

Palumbo et al randomized patients to either standard dose MP for 6 months or to MPT for six months followed by maintenance thalidomide (Table 9).197 Overall response rates were significantly higher with the MPT than the MP (76% versus 48%) as was the CR plus near CR rate (28% versus 7%). MPT also resulted in superior 2-year EFS rates (54% versus 27%, p=0.0006). No significant survival improvement has been seen even with longer follow up.203 Randomized trials led by Wijermans et al and Waage et al also do not show any significant survival benefit with MPT compared to MP201,202

MPT therapy is associated with greater toxicity than MP. Therefore not all elderly patients may be able to receive the regimen. Grade 3-4 adverse events occur in approximately 50% of patients treated with MPT, compared to 25% with MP. 197 As with Thal/Dex, there is a significant (20%) risk of DVT with MPT in the absence of thromboprophylaxis. However, this rate drops to approximately 3% with the use of thromboprophylaxis (eg., enoxaparin).197

Melphalan, Prednisone, Bortezomib (MPV)

Mateos et al have reported the first results of the novel combination MPV in newly diagnosed myeloma in patients 65 years or older. Therapy was associated with a response rate of 89%, including 32% CR rate. Approximately half of the patients with CR also had no residual bone marrow plasma cells by immunophenotypic studies. In addition, MPV appeared to overcome the poor prognosis conferred by deletion 13 and IgH translocations. Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival at 16 months were 83% and 90%, respectively. Most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were thrombocytopenia (51%), neutropenia (43%), peripheral neuropathy (17%), diarrhea (16%) and infection (16%). Herpes zoster infection occurred without prophylaxis in 13%; and was reduced to 7% in with prophylactic acyclovir. MPV appears very promising with high CR rates.

A recent randomized trial compared VMP to MP in 682 patients (Table 9).204 The time to progression among patients receiving VMP was 24 months versus 16.6 months with MP, P<0.001. Partial response or better was seen in 71% with VMP and 35% with MP; corresponding complete-response rates were 30% versus 4%, respectively (P<0.001). Overall survival was significantly better with VMP, p=0.008. Grade 3 events occurred more often with VMP versus MP (53% vs. 44%, P=0.02). Grade 3 neuropathy was seen in 13% with VMP. This study established the superiority of VMP over MP in myeloma.

Melphalan, Prednisone, Lenalidomide (MPR)

Palumbo and colleagues have studied the addition of lenalidomide to MP in newly diagnosed patients older than 65 years of age.205 Fifty-four patients were studied. At the maximum tolerated dose, the overall response rate was 81%, with 48% of patients achieving at least very good partial response (VGPR) or better, and 24% of patients achieving CR. Major grade 3-4 adverse events were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, rash and febrile neutropenia. All patients received prophylactic aspirin; DVT was uncommon, occurring in 3 patients 6% including two after aspirin discontinuation. Most patients needed growth factor support. Based on this trial, MPR appears to be a very effective oral regimen for the treatment of elderly patients with multiple myeloma who are not candidates for ASCT. An ECOG randomized trial is comparing MPR to MPT.

HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELL TRANSPLANTATION

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT)

Although not curative, ASCT improves complete response rates and prolongs median overall survival in myeloma by approximately 12 months.206-209 The mortality rate is 1-2%. The major studies that established the role of ASCT in myeloma are listed on Table 9. Melphalan, 200 mg/m2 is the most widely used preparative (conditioning) regimen for ASCT. It is superior to the older regimen of melphalan 140 mg/m2 and 8 Gy total body irradiation (TBI).210 Studies are ongoing to determine if the conditioning regimen can be improved with the addition of radioactive compounds (Holmium (HO166 DOTMP) or Samarium 153-SM-EDTMP)211,212 or bortezomib.

Three randomized trials show that survival is similar whether ASCT is done early (immediately following 4 cycles of induction therapy) or delayed (at the time of relapse as salvage therapy)(Table 9).213-215 In a Spanish PETHEMA group randomized trial, patients responding to induction therapy had similar overall and progression free survival with either ASCT or 8 additional courses of chemotherapy,216 suggesting that the greatest benefit from ASCT may be in those with disease refractory to induction therapy.217,218

There is little doubt that ASCT prolongs survival in myeloma, but its timing (early versus delayed) is controversial. Overall, given the inconvenience and side-effects of prolonged chemotherapy, insurance, and other issues we still favor early ASCT, especially for patients less than 65 years of age with adequate renal function.208 However, given effective new agents to treat myeloma, some patients and physicians may choose to delay the procedure. The need for early ASCT is an important question for future clinical trials.

Tandem transplantation

With tandem (double) ASCT, patients receive a second planned ASCT after recovery from the first procedure (Table 11).219,220 The recent IFM 94 randomized trial found significantly better event-free and overall survival in recipients of double versus single ASCT (Table 9).221 A similar benefit was also demonstrated in a randomized trial conducted in Italy;222 two other randomized trials are yet to show significant improvement in overall survival with tandem ASCT, but they have shorter follow up.223,224

Table 11.

Randomized Trials Comparing Conventional Chemotherapy Versus Single Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

| Trial | No. of patients | CR/VGPR, % | PFS, mo | OS, mo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCT | ASCT | CCT | ASCT | CCT | ASCT | ||

| IFM90206,288 | 200 | 13 | 38* | 18 | 28* | 44 | 57* |

| MRC7207 | 401 | 8 | 44* | 20 | 32* | 42 | 54* |

| MAG91289 | 190 | 4 | 6 | 19 | 25* | 48 | 48 |

| MAG90**213 | 185 | 57 | 20 | 13 | 39 | 64 | 65 |

| PEETHMA284 | 164 | 11 | 30* | 33 | 42 | 61 | 66 |

| S9321**282 | 516 | 17 | 15 | 7 yr 14% | 7 yr 17% | 7 yr 38% | 7 yr 38% |

| MMSG†,290 | 194 | 6 | 25* | 16 | 28* | 42 | 58+* |

| HOVON- 24‡,291 | 303 | 13 | 28* | 23 | 24* | 50 | 55 |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CCT, conventional chemotherapy; CR/VGPR, complete response or very good partial response; ORR, any response greater than or equal to a partial response; PFS, progression free survival; OS, overall survival;

Significant

Trials testing early versus delayed autologous stem cell transplant

Transplant arm is 2 low dose (melphalan 100 mg/m2) autologous stem cell transplants

Could be considered “double transplant” since both arms received melphalan 70 mg/m2 × 2 without stem cell support as induction therapy

Reproduced with permission from Dispenzieri, A et al. Mayo Clinic Proc 2007;82:323-341. © Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

In both the French and Italian trials, the benefit of a second ASCT was restricted to patients failing to achieve a complete response or very good partial response (>90% reduction in M protein level) with the first procedure. Based on these results, we now routinely collect enough stem cells for two transplants in all eligible patients. Patients achieving a complete response or very good partial response with the first transplant are observed or offered clinical trials investigating maintenance therapy, reserving the second ASCT for relapse.225 Patients not achieving such a response are offered a second ASCT.

Allogeneic Transplantation

The advantages of allogeneic transplantation are lack of graft contamination with tumor cells and presence of a graft versus myeloma effect.226,227 However, only 5%-10% of patients are candidates because of age, availability of a HLA matched sibling donor, and adequate organ function. Further, the high treatment related mortality (TRM), mainly related to graft versus host disease (GVHD) has made conventional allogeneic transplants unacceptable for most patients with myeloma.

Several recent trials have been conducted using non-myeloablative conditioning regimens (mini-allogeneic transplantation).228 Initial trials evaluating this approach included relapsed or refractory patients, which was thought to account at least in part for the poor outcomes. It also became apparent that this approach was less useful in patients who had significant residual tumor burden at the time of the non-myeloablative transplant, which led to the concept of a planned autologous SCT followed by a planned reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplant (RIC SCT) a couple of months later.229 The initial studies had treatment related mortalities approaching 25%, 3-year overall survival and progression-free survival rates were 41% and 21%, respectively.229 Adverse OS was associated with chemoresistant disease, more than 1 prior transplantation, and absence of chronic GVHD. Using the planned tandem autologous/nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation approach, outcomes have been better with treatment-related mortalities of 15% and 2 year overall survivals approaching 75%.230 However, there is also a high risk of acute and chronic GVHD, and the occurrence of GVHD appears necessary for disease control.

A French randomized trial addressed the role of allogeneic stem cell transplant in high risk patients as defined by the presence of deletion 13 by FISH and of beta-2 microglobulin greater than 3 mg/L.231 Based on biological randomization, patients were allocated to either double autologous stem cell transplant or to autologous SCT followed by a RIC allogeneic SCT. Though patients did better than expected in both arms, with median overall survivals of 41 and 35 months, respectively, there was no significant difference between the 2 arms with a median follow-up of 24 months. The major criticisms of this study have been that the criteria used to select ‘high-risk’ disease did not select for the highest risk patients; and that the reduced intensity conditioning used may have been too immunosuppressive, thereby abrogating the graft versus myeloma effect.

In contrast to the French trial, a significant survival advantage was seen with ASCT followed by a RIC allogeneic SCT compared to tandem ASCT in a randomized trial conducted in Italy,. On an intent to treat basis, the median overall and event-free survival were longer with autologous SCT followed by an RIC compared to tandem ASCT (80 months vs. 54 months, p=0.01; and 35 months vs. 29 months, p=0.02, respectively).232 However, the sample size was modest (n=162), and additional confirmation is needed.

A subsequent trial investigating non-myeloablative transplants in myeloma strikes a note of caution. In this Spanish trial reported by Rosinol et al,233 110 patients with myeloma failing to achieve near-complete remission (nCR) after first ASCT were assigned to a second ASCT (85 patients) or a reduced-intensity-conditioning allogeneic transplantation (allo-RIC; 25 patients), based on the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–identical sibling donor availability. Although the CR rate was superior with allo-RIC (40% vs 11%, P = 0.001) transplantation-related mortality was higher (16% vs 5%, P = .07), and no benefit was seen with regards to overall survival. In addition, allo-RIC was associated with a 66% rate of chronic graft-versus-host disease. and no statistical difference in event-free survival and overall survival. At this time, mini-allogeneic transplantation remains investigational. It should only be considered in the context of clinical trials in standard-risk myeloma because current results with the tandem ASCT strategy described earlier yields 7-year survival rates in excess of 40%. In these patients the treatment related mortality and GVHD rates with non-myeloablative allogeneic transplantation are unacceptably high.

TREATMENT OF HIGH-RISK MYELOMA

Patients with high-risk myeloma tend to do poorly with median overall survival of approximately two years even with tandem ASCT. The main option for these patients is novel therapeutic strategies.2,79 Bortezomib containing regimens should be considered early in the disease course as primary therapy. In at least 3 separate studies, bortezomib appears to overcome the adverse effect of deletion 13.234-236 Due to the high risk of early relapse, stem cell transplantation is best reserved for relapse. Routine maintenance therapy could be considered (eg., lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone) given the high risk of early relapse. Clearly clinical trials and new agents specifically designed for high-risk myeloma are needed.

MAINTENANCE THERAPY

Maintenance therapy with interferon-α is of limited value and is seldom used.237 Recent results from a large intergroup study showed no benefit with interferon as maintenance therapy.215 A study by Berenson and colleagues suggests that prednisone may be useful for maintenance therapy.238 Progression-free survival (14 versus 5 months) and overall survival (37 versus 26 months) were significantly longer with 50 mg versus 10 mg of prednisone orally every other day. Since this comparison included only those who responded initially to steroid-based therapy and since patients did not receive ASCT, it is difficult to generalize these results to current practice. Clinical trials are currently evaluating thalidomide, dendritic cell vaccination, and other novel approaches as maintenance therapy.