Abstract

Family stress theory can explain associations between contextual stressors and parenting. However, the theory has not been tested among Mexican Americans or expanded to include cultural-contextual risks. This study examined associations between neighborhood, economic, and acculturative stressors and parenting behaviors in a sample of 570 two-parent Mexican American families. Results support the negative impact of economic stress on parenting through parental depressive symptoms. Neighborhood stress influenced fathers’ depressive symptoms and parenting, but not mothers’. The effects of acculturative stress were inconsistent. Results suggest that contextual stressors common to Mexican American families impact parenting behaviors through parental depression.

Keywords: Culture, Economic hardship, Mexican American, Neighborhood, Parenting

Ethnic minority groups are disproportionately exposed to a myriad of contextual stressors, including poverty, poor quality neighborhoods, and cultural stressors. For instance, almost 22% of Latinos live below the federal poverty level compared to less than 9% of non-Latino Whites (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005). Many Latinos live in low quality neighborhoods (Moore & Pinderhughes, 1993). Additionally, over 70% of Latinos speak a language other than English at home (U.S. Census, 2000), and many of these do not speak English well (Shin & Bruno, 2003). Consequently, a large proportion of Latinos may face stressors associated with acculturation processes (e.g., pressures to know/use English), in addition to the stress associated with poverty and disadvantaged neighborhood conditions. This study focused on Mexican Americans, who are the largest ethnic group among U.S. immigrants and represent about two-thirds of U.S. Latinos (Ramirez & de la Cruz, 2003). Epidemiologically, Mexican Americans are at an increased risk for negative developmental outcomes, which may, in part, be due to their exposure to poverty, poor quality neighborhoods, and cultural stressors (Adler et al., 1994; Bhui et al., 2005).

Several individual characteristics and proximal processes, including parental psychological distress and parenting, have been investigated as mediators of the relations between contextual risks and negative outcomes in children and families. Parenting behaviors are critical shapers of child development (Colder, Mott, Levy, & Flay, 2000; Kilgore, Snyder, & Lentz, 2000) and there is abundant evidence linking parental psychopathology to impairments in parenting behaviors (Jones, Forehand, Brody, & Armistead, 2003). Specific implications of parental psychological distress include the inability to be warm and consistent, lack of meaningful interactions, feelings of rejection and hostility, and lack of parenting self-efficacy (Downey & Coyne, 1990). Parental depression also can disrupt parents’ ability to monitor children (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Jones et al., 2003) and provide consistent discipline (Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002; Kotchick, Dorsey, & Heller, 2005). However, most of this research was conducted with other ethnic groups. Because contextual risks are disproportionately experienced by Mexican Americans, research is needed to understand the effects of multiple contextual risk factors on parental psychopathology and parenting behaviors in this group.

Family stress theory posits that the relations between contextual stressors and impaired parenting are mediated by caregiver psychological distress and that impaired parenting compromises child adjustment. To date, much of the research employing family stress theory has examined the impact of low income status and economic distress on parenting (e.g., Conger, Rueter, & Conger, 2000; Conger et al., 2002). However, Kotchick, Dorsey, and Heller’s (2005) work extended this theory to examine the impact of neighborhood stressors, such as the stress of living in dangerous neighborhoods, on parents’ psychological distress and parenting. The extension of family stress theory from economic stress to stresses experienced as a part of living in a poor quality, dangerous neighborhood is an important one. However, a cultural extension may also prove useful in adapting the model for use with Mexican American families. Specifically, acculturative stress, or stressful experiences that occur as part of the process of adapting to the language, lifestyles and rules of another country (Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002) may be another important source of stress that produces within-group variation in parental depression and parenting behaviors among Mexican Americans. A more complete model would simultaneously examine financial, neighborhood, and acculturative stressors because these problems often co-occur.

Economic hardship and neighborhood danger are two chronic stressors that individuals face on a daily basis (Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, 1994; McLoyd, 1990). Several studies have demonstrated associations between financial hardship or neighborhood quality, including danger, and parent psychological distress and parenting behaviors (e.g., Elder, Eccles, Ardelt, & Lord, 1995; Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002; Kotchick et al., 2005). All of these studies involved samples of African American, European American, or mixed origin families and provided evidence that maternal psychological distress mediates the relations of both family financial hardship and neighborhood danger with parenting behaviors. For instance, Elder and colleagues reported that family hardship and economic pressure, indirectly through parental depressed mood, reduced caregivers’ sense of parenting efficacy and, for some, the quality of their parenting behavior. Other studies have shown that similar financial hardship models hold for both fathers and mothers (Conger & Conger, 2002; Conger et al., 1993; Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994). Kotchick and colleagues showed that higher perceived neighborhood stress, including stress from living in a dangerous neighborhood, predicted increased parent psychological distress that, in turn, was related to less positive parenting (including lower monitoring and disciplinary consistency). Similarly, Hill and Herman-Stahl found that mothers’ depression mediated the relation between neighborhood safety and inconsistent discipline.

The studies reviewed thus far utilized samples of European American and African American families. Thus, the degree to which the same associations between economic hardship or neighborhood danger and parental distress or parenting hold for Mexican Americans is unknown. Differences in (a) family structure and (b) cultural values between Mexican Americans and those included in previous tests of the family stress process model reinforce the importance of testing the model with Mexican American families. For example, many of the families in previous neighborhood research were single-parent, mother-headed, low-income families. Two-parent households are the norm among Mexican Americans, even those in poverty. Work by Parke et al. (2004) extended previous economic hardship findings to Mexican American two-parent families. Loukas, Prelow, Suizzo, and Allua (2008) found that cumulative familial risks (i.e., neighborhood problems, financial strain, and maternal depression) negatively influence low-income Latino mothers’ parenting behavior. However, neither study allows for the identification of the pathways through which multiple contextual stressors simultaneously impact parenting in a Mexican American sample that is diverse with regards to levels of acculturation/enculturation, generational status, and socioeconomic and neighborhood circumstances.

Parenting behaviors are influenced by cultural values and cultural processes (Chao, 2000; Chao & Tseng, 2002). Further, members of different cultural groups may experience stronger or weaker reactions to common stressors (Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, & Jones, 2001). That is, there is likely to be considerable variability in processes associated with parenting behaviors both between and within cultural groups (Murry, Smith, & Hill, 2001). Identifying pathways of contextual risk among a diverse sample of Mexican American families is critically important because the family stress model may operate differently (a) between Mexican Americans and other groups to which the model has previously been applied and (b) among Mexican Americans of various acculturation levels.

Culturally, in the context of the traditional values of respect and familism, the level of warmth and discipline in the entire family/extended family may be more important to children than any one parent’s behavior. Second, among two-parent families, especially those that espouse more traditional attitudes toward gender (e.g., clear and distinct male and female roles), mothers and fathers may attend to, or respond to, different kinds of contextual stressors. Finally, recent work with Mexican Americans suggests that parental depression may be uniquely related to different parenting behaviors (Cabrera, Shannon, West, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). Consequently, prior approaches that have either examined a multidimensional parenting latent construct (R. D. Conger, Patterson, & Ge, 1998) or a single parenting behavior (Parke et al., 2004), may miss important differences in the way that that the model operates with regards to different parenting outcomes among Mexican American parents.

Warmth may play a unique role in parenting in different cultures (Wu & Chao, 2005). Work with European Americans and African Americans has consistently found that the family stress model explains variation in warmth and control behaviors (R. D. Conger et al., 1992; R. D. Conger, Conger et al., 1993; R. D. Conger et al., 1998). However, Grusec, Rudy, and Martini (1997) reported that control behaviors in families from more collectivist cultures may reflect a culturally-sanctioned model of good parenting. In families from collectivist cultures such as Mexico (Vázquez García, García Coll, Erkut, Alarcón, & Tropp, 1999), high levels of control are not necessarily the result of stress and need not be accompanied by low levels of closeness, or warmth, as in European American families (Carlson & Harwood, 2003; Ispa, 1994). Therefore, it is especially important to examine factors influencing parental warmth because it may be an important component of parenting among Mexican American families employing high levels of control (Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003).

It is equally important to examine the consistency of control-related behaviors, such as consistent discipline, among Mexican American families. Previous work with adolescent-aged children shows that Latino families employ higher levels of control than European American families (Varela et al., 2004) and Halgunseth, Ispa, and Rudy (2006) hypothesized that the use of control related behaviors among Latino families may reflect specific cultural goals, such as familism and respect. Relatively little research has examined the consistency of control in these groups (see Hill et al., 2003, for an exception). The use of control among Mexican origin parents may be a response to contextual circumstances encountered in the U.S. (Varela et al., 2004) and may change with increases in acculturation (Buriel, 1993; Zapata & Jaramillo, 1981). Consequently, the consistency of control-related behaviors may wane as Mexican-origin parents acculturate or experience acculturative stressors (Samaniego & Gonzales, 1999).

Cultural stressors, which have not been considered in the family stress model, are particularly important to consider when studying Mexican American families given their cultural differences with mainstream U.S. families and the large portion of the population who are immigrants to the U.S. Acculturative stress directly results from the acculturation process (Berry, 1990) and may include language difficulties, feelings of not belonging, and stress associated with reconciling the values, norms, and customs of the host society with the culture of origin (Hovey, 2000). English competency pressures are considered to be a source of stress distinctly associated with the acculturation process, as opposed to other stressors that may be experienced because of one’s minority status (e.g., discrimination, stereotyping,) or socioeconomic positioning (Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002). English competency pressures can be experienced in both early and later generations (especially if later generations have been living in ethnic enclaves). Unlike English proficiency, a common proxy for acculturation status (Cabrera et al., 2006), the English competency pressures construct is sensitive to the fact that not all Mexican Americans who speak Spanish are (a) going to experience pressures to speak English or (b) going to necessarily have low SES.

The effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on families and children are poorly understood. Research has shown that acculturation and acculturative stress, including language difficulties, are related to psychological health in Hispanic adolescents and adults (Gonzales et al., 2002; Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993). However, the effects of acculturative stress on psychosocial variables, such as parenting behavior, are equivocal. Indeed, the process of acculturation has been shown to have quite distinct and opposite effects on psychosocial variables depending on whether the effects of socioeconomic status are parceled out (Gonzales, Barr, & Formoso, 1997). Though Parke and colleagues (2004) found that increases in acculturation status were associated with decreases in hostile parenting among Mexican Americans, their study did not examine the impact of stressors associated with specific acculturation processes, such as English competency pressures. In the current study, we simultaneously consider the influence of pressures to use English, financial hardship, and neighborhood danger to more accurately reflect the life circumstances of Mexican American families.

Prior research on the family stress model generally found the model to work similarly for boys and girls (R. D. Conger et al., 1992; R. D. Conger, Conger et al., 1993). On the other hand, Mexican American families have generally been found to have more traditional attitudes toward gender than European American families (Marin & Marin, 1991). In the context of traditional gender role values, the model may work differently for boys and girls. Specifically, more traditional Mexican American parents’ parenting behavior toward a son or a daughter may be influenced by different contextual stressors. For example, neighborhood danger may be especially influential on parenting behavior directed toward girls, if more traditional parents feel that girls are in more need of protection from such dangers.

The current study tested a family stress model of contextual stressors, parent psychological distress, and positive parenting behaviors within a sample of Mexican American mothers and fathers. This study extended the current literature in five important ways. First, it built upon the work of Kotchick and colleagues (2005) by examining parents’ perceptions of the degree of danger in their neighborhoods from a family stress theoretical perspective. Second, it further extended family stress theory by examining the unique contributions of three correlated contextual stressors (neighborhood danger, economic hardship, and English competency pressures) simultaneously, whereas most research has examined neighborhood, economic, and cultural stressors independently. Indeed, by identifying and isolating three distinct sources of stress that Mexican origin parents may experience, the current research facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the adjustment/parenting challenges facing this group (Rodriguez et al., 2002). Third, the research offered a cultural extension of family stress theory by including English competency pressures as a cultural-contextual stressor that may influence Mexican American family functioning. Fourth, it examined these relations in a very diverse sample of Mexican Americans, a group that rarely has been included in research on the family stress model (see Parke et al., 2004 for an exception) or neighborhood danger.

Finally, this study focused on two-parent families and included fathers. This was the first study to test an expanded family stress model (i.e., one that examined multiple contextual stressors simultaneously) to explain variation in Mexican American fathers’ parenting in addition to mothers’ parenting. Recent extensions of the family stress model to neighborhood contexts have yet to investigate the role of neighborhood danger on fathers’ psychological distress and parenting behaviors. Reviews, however, have emphasized the importance of fathers in the lives of children (Lamb, 1998; Marsiglio, Amato, Day, & Lamb, 2000), especially Latino children (Cabrera & Garcia Coll, 2004), and such work is particularly relevant in a study of Mexican American families, where two-parent families are more prevalent (Upchurch, Aneshensel, Mudgal, & McNeely, 2001).

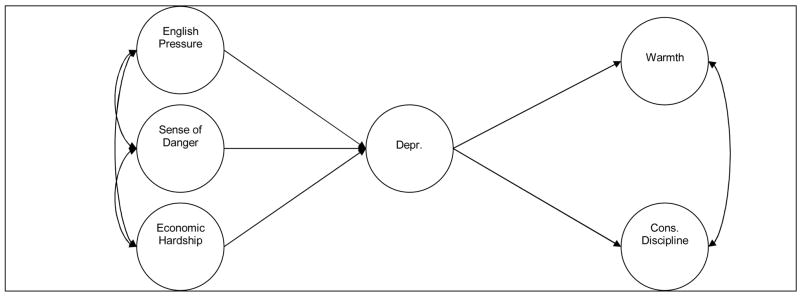

The hypothesized model is presented in Figure 1. Consistent with the family stress model, we hypothesized that contextual stressors, namely neighborhood danger, economic hardship, and English competency pressures, would contribute to parental psychological distress that, in turn, would have a negative impact on parental warmth and consistent discipline. As per the noted differences between Mexican Americans and those groups included in previous studies of the family stress model (e.g., family structure and cultural values), we speculate that the associations may be more nuanced, however. For example, given the potential for traditional gender role values to impact the family stress model, we tested child gender as a modifier of the structural relations in the hypothesized model.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Structural Model of Contextual Stress and Parenting Behavior.

Note.: Cons. Discipline = Consistent discipline.

Method

Data for this study come from the first wave of an ongoing longitudinal study investigating the role of culture and context in the lives of Mexican American families in a large metropolitan area in a southwestern state (Roosa, Liu, & Torres, 2008). Participants were 750 students in 5th grade and their families who were selected from school rosters in areas that served ethnically and linguistically diverse communities. Eligible families met the following criteria: (a) they had a fifth grader; (b) the participating mother was the child’s biological mother, lived with the child, and self-identified as Mexican or Mexican American; (c) the child’s biological father was of Mexican origin; (d) the target child was not severely learning disabled; and (e) no stepfather was living with the child. The current analyses were conducted on the subset of families in which both mother and father participated.

There were a total of 570 two-parent families in the study; in 467 (82%) of these both parents participated and were interviewed. Twelve were excluded due to incomplete data. Among the remaining 455 parents, 393 (86%) were married, and 62 (14%) were unmarried partners. Given the choice of completing the battery in English or Spanish, 73% of mothers and 77% of fathers chose to complete their interviews in Spanish. For children, only 19% chose to complete the battery in Spanish. Mothers and fathers were largely first and second generation, but approximately 16% were from later generations. Children represented first (33%), second (43%), third (10%) and fourth or higher (15%) generations. For fathers, 91% were employed full time; for mothers this figure was 39%. Average age was 35.6 years (SD = 5.6) for mothers; and 38.0 years (SD = 6.2) for fathers. Years of education ranged from 1 to 20 (M = 10.1) for fathers and 1 to 19 (M = 10.3) for mothers. The modal annual income for the families in this study was between $25,001 – 30,000, but ranged from less than $5,000 to greater than $95,000.

Procedures

Details of the study procedures are provided elsewhere (Roosa et al., 2008). Here, we briefly review the sampling and interviewing procedures. Using a combination of random and purposive sampling, the research team identified 47 public, religious, and charter schools from throughout the metropolitan area to represent the economic, cultural, and social diversity of the city. Recruitment materials requesting permission to contact the family (in Spanish and English) were sent home with all children in the 5th grade in the selected schools. A group of prominent individuals closely connected to the local Latino and education communities were recruited to serve on an advisory board to the project. The board’s establishment and recommendations facilitated positive relations between the project, local educators, and Mexican American community members. Additionally, to improve the return rate for the forms, the project offered two incentives: (a) a pizza party for every classroom with an 80% or higher return rate and (b) a $25 gift certificate for teachers whose class had the highest return rate in their school. Average classroom response rates were over 86%. Of those who returned the recruitment materials, 51% met eligibility criteria. Trained interviewers conducted Computer Assisted Personal Interviews (CAPIs) with 750 families, 73% of those eligible. Mothers (required), fathers (optional), and children (required) participated in the in-home CAPIs, lasting an average of about 2½ hours. Each family member was interviewed by a separate trained, bilingual interviewer in separate locations throughout the home. Questions and response options were read aloud to control for variability in literacy. Each participating family member was paid $45. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the first author’s university and conformed with APA ethical standards.

Measures

Sense of neighborhood danger

Parents’ perceptions of the degree of danger in their neighborhoods were assessed using a 3-item subscale of the Neighborhood Quality Evaluation Scale (NQES, Roosa, Deng, Ryu et al., 2005). The NQES is composed of several additional items and subscales taken from many commonly used measures of neighborhood context. The three items used in the current study are the only ones that have demonstrated evidence of cross-language and cross-cultural equivalence (Kim, Nair, Knight, & Roosa, in press), indicating that the measure is similarly reliable and valid across Spanish and English speakers. The three items were used as indicators of a latent construct representing mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of neighborhood danger. Parents were asked to indicate their levels of agreement ranging from 1 = not true at all to 5 = very true on the following items (all reverse coded): “it is safe in your neighborhood,” “your neighborhood is safe for children during the daytime,” and “it is safe for children to play outside your home.” Higher scores reflect higher sense of danger in the neighborhood.

Economic hardship

Economic hardship is a more proximal predictor of family/child processes than socioeconomic status (Roosa, Deng, Nair, & Lockhart Burrell, 2005), and may be an especially appropriate choice for a multigenerational sample of Mexican Americans because prior work has shown that traditional assessments of socioeconomic status may underestimate actual financial resources available to immigrant families (Tienda & Raijman, 2000). Our measure of economic hardship had three subscales reflecting (a) an inability to make ends meet (2 items, e.g., “tell us how much difficulty you had with paying your bills”), (b) not enough money for necessities (7 items, e.g., “You had enough money to afford the kind of food you needed”), and (c) financial strain (2 items, e.g., “how often do you expect that you will have to do without the basic things that your family needs”). Items on these subscales are either directly from or derived from the economic hardship measure developed by Conger and colleagues (Conger et al., 1994). Scoring is done by taking a mean of the items within each subscale. Higher numbers represent greater financial strain, greater inability to make ends meet, and a greater sense of not having enough money for one’s needs, respectively. In the current study, subscale scores were used as indicators of the latent construct economic hardship, consistent with prior research on economic hardship (R. D. Conger et al., 2002).

English competency pressures

English competency pressures were assessed using a five-item measure based on a scale developed by Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, and Garcia-Hernandez (2002). This scale measures how often the parents experienced problems due to a lack of English proficiency (e.g., “you have difficulties because you do not speak English or do not speak it well”), on a response scale ranging from 1 = not true at all to 5 = very true, with higher scores indicating higher levels of stress. The five items of this scale were used as indicators of the English competency pressures construct.

Parent psychological distress

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptomatology in the general population. The scale has four subscales: depressive affect, lack of well-being, interpersonal difficulties, and somatic symptoms. Fathers and mothers responded to statements such as, “You were bothered by things that usually don’t bother you” using a response scale ranging from 1 = rarely or none of the time to 4 = most or all of the time. Prior work has shown acceptable reliability and validity of this scale in research with Spanish- and English-speaking Latinos (Mosicicki, Locke, Rae, & Boyd, 1989). The four CES-D subscale scores were used as indicators of the continuous latent construct depressive symptoms, an approach that is consistent with prior family stress model work (Parke et al., 2004).

Warmth and consistent discipline

The parenting measures were based upon Schaefer’s (1965) Child Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI), which was developed to assess children’s perceptions of their parents’ behaviors. It has since been adapted to assess parents’ perceptions as well (Barrera et al., 2002). The measure has been shown to be acceptably reliable and valid in Spanish- and English-speaking Latino groups, as well as demonstrating evidence of cross-language equivalence (Knight & Hill, 1998; Roosa, Tein, Groppenbacher, Michaels, & Dumka, 1993). We used two subscales: acceptance and consistent discipline. The acceptance subscale is a seven-item measure that assesses warmth within the parent-child relationship (e.g., “You spoke to [child name] in a warm and friendly voice”). The consistent discipline subscale also is a seven-item scale that measures how consistently the parent responds to the child’s needs or misbehaviors (e.g., “When you made a rule for [child name], you made sure it was followed”). Mothers, fathers, and children (reporting separately on mothers and fathers) were asked how often parents performed the behavior described in the item and responded on a five-point Likert scale from almost 1 = never to 5 = almost always. For the analyses, items from each subscale were used to form the respective latent constructs.

Data Analysis

In recognition of the sampling design (i.e., families nested within communities), we examined intraclass correlations and design effects for all study variables. All design effects were less than 2.0, suggesting that the clustered nature of the sampling design could be ignored and traditional statistical techniques could be employed without concern for bias (B. O. Muthén & Satorra, 1995). Therefore, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the hypothesized relations. Analyses proceeded in two steps. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to evaluate the fit of the measurement model for all constructs. Upon having established a measurement model with acceptable fit, analyses proceeded with estimation of the full structural model (Figure 1).

Though only parent reports were available on the measures of contextual stress and parent psychological functioning, both parent and child report were available for the parenting variables. When working with datasets where multiple reporters are available researchers can choose to either create composite scores for the dyad or conduct separate analyses for each. However, research on parent-child agreement on parenting measures shows only low to moderate levels of agreement, suggesting that the latter choice is preferred (Tein, Roosa, & Michaels, 1994). Consistent with Tein et al., use of multiple reporters on the two parenting constructs is viewed as a replication of the test of the theoretical question posed in the conceptual model. Consequently, the hypothesized model is tested four times: twice for mothers (once with mother report on the parenting constructs and once with child report on the parenting constructs) and twice for fathers. Models were examined separately for mothers and fathers because the separate mother model offered the most direct comparison to previous research, especially neighborhood stress-process research (Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002; Kotchick et al., 2005). Analyses were conducted using Mplus statistical software (L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 2007) with a robust maximum likelihood estimator (ESTIMATOR = MLR) to provide improved standard error estimates and model fit statistics under conditions of non-normality. Several indices were used to evaluate model fit because individual fit indices are each associated with distinct biases. Specifically, we used a mean-adjusted chi-square (scaled χ2) test statistic (which adjusts for non-normality), the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI). Fit is considered good (acceptable) if the CFI is greater than or equal to 0.95 (0.90), the RMSEA is less than or equal to 0.05 (less than 0.08), and the Standardized SRMR is below 0.05 (less than 0.08) (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). To test for mediation, we used the product of coefficients method with standard errors computed using the multivariate delta method to determine whether indirect effects were statistically significant (Sobel, 1982). To test for moderation by child gender, we ran stacked models, first allowing the path coefficients to be estimated freely across boys and girls and then constraining the structural path coefficients to be equal for boys and girls. Model comparisons were conducted using the χ2 difference test outlined by Satorra and Bentler (2001), which was developed for comparing scaled χ2 values (S-B Δχ2). If the S-B Δχ2 was significant, we concluded that some paths were significantly different between the two groups and conducted subsequent analyses examining S-B Δχ2 to identify which pathways were significantly different (i.e., we compared nested models by constraining one additional structural pathway at each step to determine which constraints were leading to misfit).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alphas of observed scale scores for all the study measures are shown in Table 1. For descriptive statistics and the original covariance matrix for all 86 observed variables used in the SEM, contact the first author.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Ranges, and Reliabilities for Manifest Scales (n = 455)

| Variable | mean | SD | Range | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic hardship (M) | 2.39 | 0.81 | 1.00 – 4.69 | .78 |

| Economic hardship (F) | 2.25 | 0.77 | 1.00 – 4.62 | .76 |

| English competency pressure (M) | 2.43 | 1.20 | 1.00 –5.00 | .87 |

| English competency pressure (F) | 1.99 | 0.94 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .83 |

| Sense of danger (M) | 2.50 | 0.99 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .88 |

| Sense of danger (F) | 2.41 | 0.93 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .88 |

| Depressive symptoms (M) | 1.71 | 0.48 | 1.00 – 3.45 | .89 |

| Depressive symptoms (F) | 1.54 | 0.43 | 1.00 – 3.35 | .88 |

| Mother warmth (M) | 4.49 | 0.51 | 2.43 – 5.00 | .83 |

| Mother warmth (C) | 4.44 | 0.64 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .84 |

| Father warmth (F) | 4.27 | 0.56 | 2.57 – 5.00 | .78 |

| Father warmth (C) | 4.37 | 0.73 | 1.29 – 5.00 | .88 |

| Mother consistent discipline (M) | 4.02 | 0.74 | 1.57 – 5.00 | .81 |

| Mother consistent discipline (C) | 3.98 | 0.76 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .79 |

| Father consistent discipline (F) | 3.64 | 0.82 | 1.14 – 5.00 | .82 |

| Father consistent discipline (C) | 3.94 | 0.92 | 1.00 – 5.00 | .87 |

Measurement Models

We began by estimating the measurement models for both mothers and fathers for the sense of danger, economic hardship, acculturative stress, depression, warmth, and consistent discipline factors. The measurement models were replicated with children report on the latter two constructs. The first step was to specify a measurement model for each latent construct separately. Results from the single factor measurement models were used to inform specification of the full measurement model. We originally specified a measurement model that did not allow for unique factor variances to correlate. However, we examined modification indices to guide the addition of correlated residual variances, as long as the change was justifiable either from a theoretical or empirical (e.g., shared stem) basis.

In the final measurement model, some residual variances were allowed to correlate based upon statistical and theoretical considerations. The models demonstrated reasonable fit with the data for mothers’ reports on their own parenting [χ2 (354) = 618.49, p <.001; CFI =.94; RMSEA =.04; and SRMR =.05], fathers’ reports on their own parenting [χ2 (354) = 654.24, p <.001; CFI =.93; RMSEA =.04; and SRMR =.06], children’s reports on mothers’ parenting [χ2 (353) = 515.33, p <.001; CFI =.97; RMSEA =.03; and SRMR =.04], and children’s reports on fathers’ parenting [χ2 (353) = 623.35, p <.001; CFI =.95; RMSEA =.04; and SRMR =.05]. All items had a standardized loading greater than 0.40 on their respective factors, suggesting that the selected indicators were reasonable representations of the latent constructs. Intercorrelations between latent variables in the mother and father models are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The measurement models were used as a basis to test the full structural model. (The final measurement models are available by request from the first author.)

Table 2.

Intercorrelations among Latent Factors in Mother Models (n = 455)

| Factor | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Economic hardship | 1 | .41* | .37* | .50* | −.11 | −.18* |

| 2. English Pressure | .45* | 1 | .18* | .43* | .00 | −.06 |

| 3. Sense of danger | .20* | .18* | 1 | .16* | .10 | .08 |

| 4. Depressive symptoms | .49* | .42* | .16* | 1 | −.06 | −.07 |

| 5. Warmth | −.07 | .12* | −.09 | −.20* | 1 | .67* |

| 6. Consistent discipline | −.15* | −.09 | −.10 | −.26* | .68* | 1 |

Note: correlations below the diagonal are for mother report models; correlations above the diagonal are for child report models.

p <.05

Full Structural Models

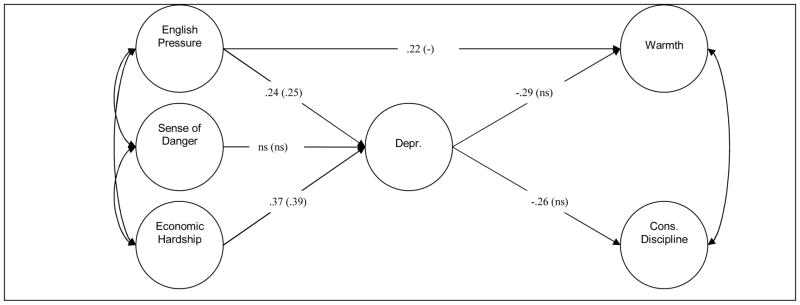

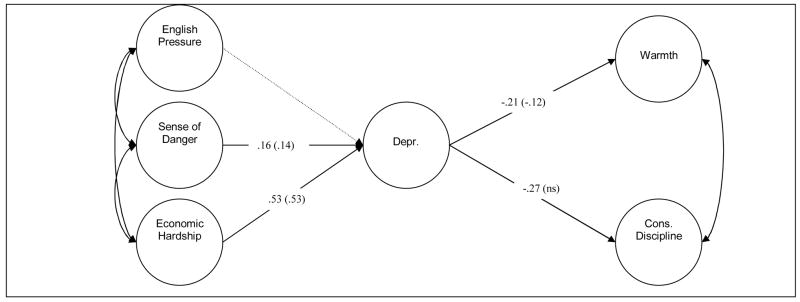

The results for the mother and father structural models are presented in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. All models were initially tested according to the hypothesized model shown in Figure 1. However, we examined modification indices to ensure that we accurately represented the data and freed constraints when it would result in substantial changes to the model fit or substantive findings. This only resulted in a change to one model, the mother-report model. The final models demonstrated good to adequate fit to the data. However, there were differences in the pattern of results between mothers and fathers and across reporters.

Figure 2. Standardized Coefficients for the Model of Contextual Stress and Parenting Behaviors for Mothers (n = 455).

Note.: Cons. Discipline = Consistent discipline. Coefficients in parentheses are for models run with child report on the parenting behaviors. All remaining coefficients are for models using parent report on the parenting behaviors. Solid lines are significant at p < 0.05.

Figure 3. Standardized Coefficients for the Model of Contextual Stress and Parenting Behaviors for Fathers (n = 455).

Cons. Discipline. = Consistent discipline. Coefficients in parentheses are for models run with child report on the parenting behaviors. All remaining coefficients are for models using parent report on the parenting behaviors. Solid lines are significant at p < 0.05.

For Mexican American mothers, two hypothesized stressors, economic hardship and acculturative stress, were positively associated with increased depressive symptoms, together explaining 29% of the variance in maternal depressive symptoms (see Figure 2). Mothers’ depressive symptoms were, in turn, associated with decreased warmth and disciplinary consistency, but only when using their own reports on the parenting behaviors. Mothers’ levels of depression were not related to child reports of parenting behaviors. Furthermore, mothers’ levels of acculturative stress were directly and positively related to their own reports of warmth (path added in response to modification indices). Using mothers’ own reports on parenting behavior, the final model explained 8% of the variance in warmth behaviors and 7% of the variance in consistent discipline behaviors. Using children’s reports on maternal behavior, the model explained less than 1% of the variance in warmth and in consistent discipline behaviors.

For Mexican American fathers, two of the hypothesized stressors, namely economic hardship and sense of danger in the neighborhood, were positively related to depressive symptoms, together explaining 40% of the variance in depressive symptoms (See Figure 3). Fathers’ depressive symptoms were, in turn, associated with decreased warmth and disciplinary consistency. The finding for warmth held across both father and child-report of fathers’ parenting. However, the finding for consistent discipline was not replicated using child report. Using fathers’ own reports on parenting behavior, the final model explained 4.30% of the variance in warmth behaviors and 8% of the variance in consistent discipline behaviors. Only 2% of the variance in fathers’ warmth and 1% of the variance in their consistent discipline behaviors were explained when children’s reports on parenting were used.

Table 4 contains the results of the statistical tests for mediation based upon the product of coefficients method with standard errors computed using the multivariate delta method (Sobel, 1982). For both mothers and fathers, depressive symptoms mediated the relation between economic hardship and their warmth and consistent discipline parenting behaviors when parent reports on parenting were used. Findings were replicated for children’s reports on paternal warmth. For mothers only, depressive symptoms mediated the relation between acculturative stress and both parenting behavior constructs. For fathers only, depressive symptoms mediated the relation between their sense of danger in their neighborhoods and consistent discipline. A statistical trend was found for depressive symptoms as a mediator between fathers’ sense of danger and warmth (p <.10).

Table 4.

Results of the Tests for Mediation (n = 455)

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | Z-score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers’ economic hardship → depressive symptoms → warmth (P) | −0.11 | 0.03 | −3.58* |

| Mothers’ economic hardship → depressive symptoms → consistent discipline (P) | −0.10 | 0.03 | −3.47* |

| Mothers’ English pressure → depressive symptoms → warmth (P) | −0.07 | 0.01 | −3.02* |

| Mothers’ English pressure → depressive symptoms → consistent discipline (P) | −0.06 | 0.01 | −3.02* |

| Fathers’ sense of danger → depressive symptoms → warmth (F) | −0.03 | 0.01 | −1.73† |

| Fathers’ sense of danger → depressive symptoms → warmth (C) | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.59 |

| Fathers’ sense of danger → depressive symptoms → consistent discipline (P) | −0.04 | 0.02 | −2.02* |

| Fathers’ economic hardship → depressive symptoms → warmth (P) | −0.11 | 0.05 | −2.28* |

| Fathers’ economic hardship → depressive symptoms → warmth (C) | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.97* |

| Fathers’ economic hardship → depressive symptoms → consistent discipline (P) | −0.14 | 0.08 | −2.78* |

Note: P = Parent report, C = Child report.

p <.05,

p <.10

The results demonstrated an inconsistency in the signs of the direct and mediated effects of acculturative stress for mothers. The indirect effect (i.e., through depression) of acculturative stress on warmth was negative (B = −0.03, SE = 0.02, p <.01), but the direct effect of acculturative stress on warmth was positive (B = 0.09, SE =.02 (p <.001). The total effect of acculturative stress on mothers warmth behavior was positive and significant (B =.06, SE =.02, p <.01).

We examined child gender as a potential moderator of relations in the model by running multi-group structural equation models. The chi-square difference test, adjusted using a correction factor to account for non-normality (Satorra & Bentler, 2001), was not significant for both mother models, S-B Δχ2 (6) = 10.35, p =.11 (mother report) and S-B −χ2 (5) = 6.33, p =.28 (child report). The difference test was significant for the father model using child report on the parenting measures [S-B Δχ2 (5) = 37.93, p <.001] and the father model using father report on the parenting measures [S-B Δχ2 (5) = 23.24, p <.001]. Follow-up analyses were conducted on father report models to determine if the equality constraints on the paths between the stressors and paternal depression were contributing to significant misfit. These analyses were not repeated in the child report models because the same construct reporter combinations were replicated. However, we also explored whether the equality constraints on the paths between paternal depression and the outcomes contributed to misfit and these probes were repeated in both father-and child-report models because the construct-reporter combinations were unique.

The follow up analyses showed two paths that were unique to child gender. First, the path between paternal perceptions of danger in the neighborhood and depression was significant for girls (B =.11, SE =.05= p <.05), but not boys (B =.02, SE =.04, p =.70). Though boy results precluded mediation, using father report on parenting behaviors, depression significantly mediated the association between neighborhood danger and consistent discipline for girls (Bab = −.10, SE =.05= p <.05), but the mediation was only trending for the effect of neighborhood danger on warmth (Bab = −.05, SE =.03= p <.10). This pattern of mediation for girls did not replicate using child report on the parenting measures. Using child report on the parenting measures, gender also moderated the association between paternal depression and consistent discipline. Specifically, this path was significant for boys (B = −.60, SE =.18, p <.001), but not girls (B =.24, SE =.19, p =.20). Consequently, for boys, using child report on parenting behaviors, depression significantly mediated the association between financial hardship and fathers’ consistent discipline (Bab = −.29, SE =.10= p <.001).

Discussion

Using the family stress model, the current study examined relations among three contextual stressors, depressive symptoms, and parenting within a diverse sample of Mexican American mothers and fathers. This is the first study to simultaneously investigate the impact of three contextual stressors common to Mexican American families from a family stress model perspective. Further, our Mexican American sample was very diverse, with families ranging from first generation recent immigrants to fourth generation adults with fifth generation children (Roosa et al., 2008). The use of a multi-generational sample offers a sound test of the hypothesized model and guides the development of further research questions regarding the ways that culture may influence child development (Quintana et al., 2006). The theoretical utility of the model is supported by the fact that we (a) tested the theory in a sample of Mexican Americans, a population that has rarely been studied in family stress-informed investigations, and (b) expanded the boundaries of the theory by including a culturally relevant contextual stressor. The practical utility of the model is supported by findings that demonstrated that some of the multiple contextual stressors common to Mexican American families have the potential to decrease both mothers’ and fathers’ psychological functioning and, in turn, their adaptive parenting behaviors.

Guided by the family stress model (K. J. Conger et al., 2000), we hypothesized that parental depressive symptoms would mediate the association between three contextual stressors (i.e., financial hardship, neighborhood danger, and English language pressures) and parenting behaviors (i.e., warmth and consistent discipline) for Mexican American mothers and fathers. Based on the preponderance of more traditional attitudes toward gender among Mexican Americans (Marin & Marin, 1991), we also hypothesized that child gender would moderate the family stress model. Our results showed some support for the hypothesized family stress model when parents’ reports on parenting behaviors were used and some replication when children’s reports on parenting behaviors were used. Our results also demonstrated evidence of moderation by child gender.

On average, financial hardship negatively impacted maternal and paternal warmth and consistent discipline through increases in depressive symptoms. This finding was replicated for fathers when using child report on warmth. This finding extends prior work with European and African American families (Conger & Conger, 2002; Conger et al., 1993; Conger et al., 1994) to a very diverse sample of two-parent Mexican American families and to multiple, previously unexamined, parenting behaviors.

Perceptions of living in a dangerous neighborhood were associated with higher levels of depression and, in turn, less positive parenting for fathers, but not for mothers. Most of the neighborhood effects on adult distress literature has focused on women (e.g., Cutrona et al., 2005; Kotchick et al., 2005), perhaps because the focus on disadvantaged contexts, to some degree, restricts research on disadvantaged neighborhoods to a population with a high proportion of single-parent, female-headed families (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). This scenario does not necessarily hold for Mexican Americans, where two-parent families are more common (Cabrera & Garcia Coll, 2004). Findings from the current study extend the link between neighborhood context and depression to Mexican American men. Additionally, the mediation findings extend prior work that has examined the influence of neighborhood context on African American mothers’ depression and parenting (Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002; Kotchick et al., 2005) to a sample of Mexican American fathers. Evidence suggests that living in a dangerous neighborhood negatively influences fathers’ disciplinary consistency through increases in depression. However, the test of mediation was only trending for the association between neighborhood danger and warmth in the father-child relationship. There was, overall, less variability in fathers’ warmth behaviors than in their consistent discipline behaviors, which may help to explain why mediation occurred only at the trend level.

Neighborhood danger did not influence Mexican American mothers’ depression and parenting behaviors. Bivariate correlations did show a positive and significant association between neighborhood danger and mothers’ depressive symptoms. However, when acculturative stress, economic hardship, and neighborhood danger were examined simultaneously, the unique association between neighborhood danger and mothers’ depression was not significant. Prior work with European and African American mothers that found associations between neighborhood context, maternal depression, and parenting did not examine neighborhood context simultaneously with financial hardship (Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002; Kotchick et al., 2005). Results from the current study suggest that future work should simultaneously examine these stressors because they are often co-occurring and the impact of neighborhood context on maternal depression and parenting may be better explained by the experience of financial hardship, an experience common to those living in disadvantaged and dangerous neighborhoods (Wilson, 1987). For these Mexican American mothers, it may be any stress from living in a disadvantaged, unsafe context exists because they are financially disadvantaged themselves and not from characteristics of the neighborhood itself.

However, there may be an alternative, cultural explanation for the current findings for mothers and fathers. Perhaps, Mexican American mothers are protected by marriage and a preponderance of traditional views about gender roles from having to worry about neighborhoods that they perceive to be dangerous because they had partners available to them who were able to focus on stressors associated with living in a dangerous neighborhood. Though the separate analyses conducted for mothers and fathers in the current study did not allow for statistical comparisons between the two, the pattern of findings suggests that, in these two parent families, fathers were responsive to neighborhood danger and mothers were not. The findings mirror neighborhood research with children and young adolescents. Prior work has found that boys’ mental health outcomes are influenced by neighborhood factors and girls’ are not, perhaps because males spend more time in and have more exposure to their neighborhoods (Greenberg et al., 1999; Simons et al., 1996).

Research on adult depression suggests an alternate hypothesis. Specifically, the sources of stressors associated with depression may be different for men and women (Almeida & Kessler, 1998), and women may suffer higher rates of depression because they are more vulnerable to interpersonal stressors than men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001). Such differences may be especially pronounced in Mexican American families that adhere to more traditional gender role beliefs. Perhaps Mexican American mothers from two-parent families are responsive to other sources of neighborhood stress, such as lack of collective efficacy or supportive social networks. Indeed, according to traditional gender role attitudes and values, men and women have different spheres of activity (Cauce & Rodriguez, 2002). To the degree that more traditional mothers’ responsibilities are limited to the household/familial/relational sphere, they may not be as influenced by perceptions of danger in their neighborhood. Similarly, a father’s sense of obligation to be the family protector, may dictate that he attend very specifically to neighborhood dangers. When studying a population of women without male partners or without more traditional attitudes about gender, as is likely the case in previous research, mothers’ may feel forced to attend to any and all stressors, including neighborhood danger. Future work should examine the moderating role of gender and traditional gender role values on the associations between neighborhood danger, stress, and parenting among Mexican Americans. Additionally, family structure should be considered as a potential moderator of the association between neighborhood stress and maternal depression. Indeed, the family stress model may be more or less effective in explaining the impact of neighborhoods stressors on parenting behaviors in subgroups of Mexican Americans. Such research would help elucidate the role of neighborhood danger in the family stress model for Mexican American parents.

Our hypothesis that English language pressures would be positively related to depressive symptomatology in Mexican American parents received partial support. Mothers’ depression was related to this form of acculturative stress but fathers’ was not. Drawing on some of the work on gender differences in the causes and correlates of depression (Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Conger, Lorenz et al., 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001), our measure of English language pressures included several items that are likely to influence intrapersonal relationships (e.g., “you have a hard time understanding others when they speak English,” and “people have treated you rudely or unfairly because you do not speak English well”), a domain of stress that may be more strongly related to female depression than to male depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001).

In addition to the direct association between English language pressures and mothers’ depression, English language pressures had a negative indirect effect on mothers’ warmth (through depression) and a positive direct effect on warmth. The latter finding was contrary to our hypothesized model. Overall, the findings suggest inconsistent mediation, as defined by MacKinnon, Krull, and Lockwood (2000). Whereas in a consistent mediation model the direct and indirect effects are in the same direction, in an inconsistent mediation model, the two effects are in opposite directions. There is little research in this area to explain this finding. Some work has shown that the process of acculturation can have both positive and negative effects on psychosocial variables like parenting (Gonzales et al., 1997). In support for the direct positive association, when mothers experience a contextual stressor associated with living in another culture, they may try to overcompensate for these perceived pressures on their children by offering high levels of warmth. This compensatory hypothesis receives indirect support from the fact that English language pressures were not directly related to mothers’ level of consistent discipline in the model. Still, to the degree that the stresses associated with English language pressures are associated with more depressive symptoms in mothers, there is a negative impact on both her warmth and consistent discipline behavior. Overall, however, it is important to note that the total effect (i.e., direct plus indirect effect) of English language pressures on warmth behavior was positive (consistent with the zero-order correlation), suggesting that the potential compensatory mechanisms are a stronger influence on mothers’ warmth than her depressive symptoms.

In light of the English competency pressure findings and previous findings on acculturative stress by Gonzales et al. (1997), it is clear that more research is needed to determine how English competency pressures and acculturative stress are related to psychological well-being and parenting in Mexican American families. Acculturative stress encompasses many sources of stress, including discrimination, language difficulties, feelings of not belonging, and stress associated with reconciling the values, norms, and customs of the host society with the culture of origin (Hovey, 2000). We examined one very specific source of acculturative stress, English competency pressures, and found that the family stress model needed significant adaptation to adequately represent the complex association between such pressures, maternal depression, and parenting. Indeed, the positive direct association between English competency pressures and warmth is quite outside the scope of the family stress model. Whether other forms of acculturative stress would operate similarly is unknown, though results presented here do shed light on why the associations between measures of acculturative stress and psychosocial variables are oblique in prior work (Gonzales et al., 1997). Specifically, any failure to consider both direct and indirect associations between forms of acculturative stress and psychosocial outcomes may be misleading.

For the most part, our average findings did not replicate with children’s reports on parents’ behaviors were used in the models. The only exception is for children’s reports on paternal warmth. In bivariate associations, children’s reports on parenting were correlated with parents’ reports on some contextual stressors, especially economic hardship, but the association was not mediated through depression, as our family stress model specified. Consistent with prior work (Tein et al., 1994), we viewed the test of the model with child report as a replication. From that vantage point, the results from the parent models should be viewed with caution.

However, it is possible that cultural variations among Mexican American children would lead to differences in the strength of the association between parental depression and children’s perceptions of parents’ behaviors. For example, children who place a high value on respeto, may not question the consistency of their parents’ behaviors. Specifically, when children high on respeto recognize and conform to strict generational hierarchies (Vazquez Garcia et al., 1999), they may not notice or question the consistency with which parents use discipline. Similarly, children who are high on familism may place a stronger emphasis on family-wide warmth. As such, their reports on warmth may better represent warmth in the family unit rather than warmth in a single parent-child dyad. We examined correlations between children’s reports on mothers’ and fathers’ warmth and found them to be quite high (r = 0.86), offering limited indirect support for this hypothesis. For these same children, fathers’ depression may have a stronger impact on the family than mothers’.

Finally, child gender moderated the father family stress models tested here in two important ways. First, on average, increases in neighborhood danger were associated with increases in paternal depression. However, the nested model comparison showed that this finding was significant for the girl model, but not the boy model. Consequently, depression mediated the association between neighborhood danger and paternal use of consistent discipline with daughters, but not sons. In the context of traditional gender roles, fathers with young adolescent aged daughters may worry more about dangers in their neighborhoods than fathers with young adolescent aged sons, perhaps because they see daughters as more vulnerable to neighborhood dangers than boys. Second, gender moderated the association between paternal depression and consistent discipline such that for boys, paternal depression significantly mediated the association between financial hardship and fathers’ consistent discipline, but not for girls. These findings, which were based on child report, offer a replication of the models using fathers report, at least for boys.

Though on average, especially traditional children may not question the consistency of parent’s behaviors, the boys in this study did recognize deficits in paternal disciplinary consistency. Recent qualitative and quantitative work on gender socialization among Latino families shows that girls experience more limits than boys do and that fathers, compared to mothers, do more direct gender socialization of boys (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). In the context of fewer limits and more paternal socialization, boys may (a) experience more exposure to mainstream cultural norms and (b) be exposed to a wider range of paternal parenting than girls. Perhaps some paternal rule-setting and enforcement is context specific. For example, when fathers and sons do work together, or interact outside of the home, fathers may choose to enforce different rules than they enforce in the home context, leading to overall inconsistency in disciplinary practices. Though prior work suggests that the family stress model applies reasonably well to both boys and girls (R. D. Conger et al., 1992; R. D. Conger, Conger et al., 1993), this study with Mexican Americans suggests that there may be gender differences and that such differences may be situated within cultural beliefs about traditional gender roles.

It is important to note that we examined multiple contextual stressors simultaneously. Previously, the influences of economic context (K. J. Conger et al., 2000) and neighborhood context (Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002; Kotchick et al., 2005) have been examined in isolation. As expected, these contextual stressors were correlated with one another. In addition, our zero-order correlations between neighborhood danger/economic hardship, parental depression, and parental behavior (Table 2) were in directions consistent with prior work. However, by examining multiple stressors simultaneously, we have identified specific pathways of risk for each while simultaneously controlling for the influences of the others. For example, for Mexican American fathers, neighborhood danger appears to be a unique contextual stressor above and beyond economic hardship; this, on average, is not the case for the Mexican American mothers in our study. By examining the influences of each of these important contextual stressors simultaneously, we have taken a first step toward a better understanding of the complexities of how stressors influence individuals and families as well as providing insights into potential additional pathways for interventions to prevent problems in at-risk Mexican American families.

Overall, the finding that depressive symptoms mediate the relation between some common contextual stressors and parenting behavior is important because it offers opportunities for preventive interventions to promote family health among Mexican Americans. Promoting positive parenting behaviors is important because these behaviors have been shown to be important determinants of child development and mental health outcomes (Colder et al., 2000; Fauber, Forehand, Thomas, & Wierson, 1990; Gonzales, Pitts, Hill, & Roosa, 2000; Hill et al., 2003; Kilgore et al., 2000; Roosa, Deng, Ryu et al., 2005). Our results suggest that interventions at both the community level and the parent level could promote positive parenting behaviors. At the neighborhood level, programs to decrease neighborhood danger may help to reduce father psychological distress. At the parent/family level, programs that teach parents how to cope effectively with stress, effectively manage financial resources, or learn skills to better their financial situations may help to reduce both mother and father psychological distress and ultimately promote better parenting.

Though these analyses represent the first attempt to examine Mexican American mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors in the context of multiple contextual risks, they should be viewed in light of their limitations. First, our data were self-report and cross-sectional. As a result, it is impossible to know if the relations identified in this model are causal. More longitudinal and experimental work is needed in this area. Second, relatively small portions of variation in parenting were explained by the model. By examining multiple contextual stressors, out models explained considerably more variance in maternal and paternal depression than previous work (Parke et al., 2004). Despite this fact, the model explained less of the variance in parenting behavior that prior work with European Americans (R. D. Conger, Conger et al., 1993; R. D. Conger et al., 1994). Examining cultural factors that moderate the association between parental depression and parenting behaviors will be an important next step for family stress research with Mexican Americans. In more or less acculturated groups, parenting behaviors may take on different meanings and, consequently, be differentially influenced by stress. The expansions offered by this investigation, including (a) testing a model in a sample of Mexican American families, including both fathers and mothers; (b) the simultaneous examination of multiple stressors; and (c) the addition of a cultural-contextual stressor, represent an important contribution to family stress theory and the study of ethnic minority families.

Table 3.

Intercorrelations among Latent Factors in Father Models (n = 455)

| Factor | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Economic hardship | 1 | .41* | .37* | .61* | −.09 | −.17* |

| 2. English Pressure | .41* | 1 | 0.24* | .31* | −.02 | −.13* |

| 3. Sense of danger | .38* | .24* | 1 | .35* | .09* | .02 |

| 4. Depressive symptoms | .60* | .31* | .35* | 1 | −.12* | −.09 |

| 5. Warmth | −.25* | −.05 | −.27* | −.16 | 1 | .61* |

| 6. Consistent discipline | −.27* | −.14* | −.28* | −.23* | .64* | 1 |

Note: correlations below the diagonal are for father-report models; correlations above the diagonal are for child-report models.

p <.05

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the families for their participation in the project. Work on this project was supported, in part, by NIMH grants R01-MH68920, and T32-MH018387, and by the Cowden Fellowship Program of the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University.

Footnotes

This article may not exactly replicate the final version published in the journal. It is not the copy of record.

Contributor Information

Rebecca M. B. White, Arizona State University and Prevention Research Center

Mark W. Roosa, Arizona State University and Prevention Research Center

Scott R. Weaver, Georgia State University

Rajni L. Nair, Arizona State University and Prevention Research Center

References

- Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Kessler RC. Everyday stressors and gender differences in daily distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:670–680. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.3.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attar BK, Guerra NG, Tolan PH. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events and adjustments in urban elementary-school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, et al. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family, and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Psychology of acculturation. In: Berman JJ, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation. Vol. 37. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1990. pp. 201–234. Cross-cultural perspectives. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, Weich S. Racial/ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: findings from the EMPIRIC Study of Ethnic Minority Groups in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:496–501. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buriel R. Childrearing Orientations in Mexican American Families: The Influence of Generation and Sociocultural Factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:987–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Garcia Coll C. Latino fathers: Uncharted territory in need of much exploration. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley; 2004. pp. 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Shannon JD, West J, Brooks-Gunn J. Parental interactions with Latino infants: Variation by country of origin and English proficiency. Child Development. 2006;77:1190–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson V, Harwood R. Attachment, culture, and the caregiving system: The cultural patterning of everyday experiences among Anglo and Puerto Rican mother-infant pairs. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Rodriguez MD. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: Relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2000;21:233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK, Tseng V. Parenting of Asians. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 4. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Mott J, Levy S, Flay B. The relation of perceived neighborhood danger to childhood aggression: A test of mediating mechanisms. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:83–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1005194413796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Rueter MA, Conger RD. The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The family stress model. In: Silbereisen RK, Crockett LJ, editors. Negotiating adolescence in times of social change. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:206–219. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge XJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Elder GH, Simons RL, Ge X. Husband and wife differences in response to undesirable life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:71–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Patterson GR, Ge X. It takes two to replicate: A mediational model for the impact of parents’ stress on adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 1998;66:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun YM, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, Gardner KA. Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:3. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Eccles JS, Ardelt M, Lord S. Inner-city parents under economic pressure: Perspectives on the strategies of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:771–784. [Google Scholar]

- Fauber R, Forehand R, Thomas AM, Wierson R. A mediational model of the impact of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: The role of disrupted parenting. Child Development. 1990;61:1112–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Barr A, Formoso D. Acculturation and family process among Mexican American families. Keynote address presented at the 1997 NIMH Family Research Consortium Meeting; San Antonio, TX. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez AA, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Pitts SC, Hill NE, Roosa MW. A mediational model of the impact of interparental conflict on child adjustment in a multiethnic, low-income sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:365–379. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Rudy D, Martini T. Parenting cognitions and child constructs: An overview and implications for children’s internalization of values. In: Grusec JE, Kuczynski L, editors. Parenitn gand children’s internalization of values: A handbook of conemporary theory. 259–282. New York: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth LC, Ispa JM, Rudy D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development. 2006;77:1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children’s mental health: Low-income Mexican-American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74:189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Herman-Stahl MA. Neighborhood safety and social involvement: Associations with parenting behaviors and depressive symptoms among African American and Euro-American mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:209–219. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey J. Psychosocial predictors of acculturative stress in Mexican immigrants. J Psychol. 2000;134:490–502. doi: 10.1080/00223980009598231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analyses: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ispa JM. Child rearing ideas and feelings of Russian and American mothers and early childhood teachers: Some comparisons. In: Reifel S, editor. Advances in early education and day care: Vol. 6. Topics in early literacy, teacher preparation, and international prespectives on early care. Greenwich, CT: JAI; 1994. pp. 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Brody GH, Armistead L. Parental monitoring in African American, single mother-headed families - An ecological approach to the identification of predictors. Behavior Modification. 2003;27:435–457. doi: 10.1177/0145445503255432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore K, Snyder J, Lentz C. The contribution of parental discipline, parental monitoring, and school risk to early-onset conduct problems in African American boys and girls. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:835–845. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Nair RL, Knight GP, Roosa MW. Measurement equivalence of neighborhood quality measures for European American and Mexican American families. Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20257. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Hill NE. Measurement equivalence in research involving minority adolescents. In: McLoyd V, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. pp. 183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Heller L. Predictors of parenting among African American single mothers: Personal and contextual factors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:448–460. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. Fatherhood then and now. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Men in Families: When do they get involveld? What differences does it make. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Prelow H, Suizzo M, Allua S. Mothering and peer associations mediate cumulative risk effects for Latino youth. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D, Krull J, Lockwood C. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W, Amato P, Day R, Lamb M. Scholarship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1173–1191. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JW, Pinderhughes R. In the barrios: Latinos and the underclass debate. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mosicicki EK, Locke BZ, Rae DS, Boyd JH. Depressive symptoms among Mexican Americans: The Hispanic health and nutrition examination survey. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;130:348–360. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VMB, Smith EP, Hill NE. Race, ethnicity, and culture in studies of families in context. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:911–914. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide. 4. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Parke R, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, et al. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]