Abstract

Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4, GKLF) was originally characterized as a zinc finger transcription factor essential for terminal differentiation and cell lineage allocation of several cell types in the mouse. Mice lacking Klf4 die postnatally within hours due to impaired skin barrier function and subsequent dehydration. Recently, KLF4 was also used in cooperation with other transcription factors to reprogram differentiated cells to pluripotent embryonic stem cell-like cells. Moreover, involvement in oncogenesis was also ascribed to KLF4, which is aberrantly expressed in some types of tumors such as breast, gastric and colon cancer. We previously have shown that Klf4 is strongly expressed in postmeiotic germ cells of mouse and human testes suggesting a role for Klf4 also during spermiogenesis. In order to analyze its function we deleted Klf4 in germ cells using the Cre-loxP system. Homologous recombination of the Klf4 locus has been confirmed by genomic southern blotting and the absence of the protein in germ cells was demonstrated by western blotting and immunofluorescence. Despite its important roles in several significant biological settings, deletion of Klf4 in germ cells did not impair spermiogenesis. Histologically, the mutant testes appeared normal and the mice were fertile. In order to identify genes that were regulated by KLF4 in male germ cells we performed microarray analyses using a whole genome array. We identified many genes exhibiting changed expression in mutants even including the telomerase reverse transcriptase mRNA, which is a stem cell marker. However, in summary, the lack of KLF4 alone does not prevent complete spermatogenesis.

Keywords: Krüppel-like factor 4, testis, spermiogenesis, spermatogenesis, germ cell, Cre-loxP, mouse

1. Introduction

Spermiogenesis comprises the postmeiotic differentiation of a round, immotile spermatid to a highly specialized spermatozoon. This unique cellular differentiation process involves nuclear condensation, development of the acrosome, growth of the flagellum, and removal of unnecessary cytoplasm including cell organelles as residual body. Spermiogenesis is orchestrated by a number of transcription factors including CREM, which might be considered as the best characterized factor during spermiogenesis (Behr and Weinbauer, 2001; Beissbarth et al., 2003; Sassone-Corsi, 1998). Male mice lacking CREM do not produce spermatozoa due to a complete arrest at the early round spermatid stage (Blendy et al., 1996; Nantel et al., 1996). These studies demonstrate that the lack of just a single transcription factor can totally block spermiogenesis. We have shown that also the zinc finger transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) is highly expressed in postmeiotic germ cells of the human and mouse testis (Behr et al., 2007a; Behr and Kaestner, 2002). KLF4 is known to be involved in important cellular processes, e.g. terminal differentiation of epithelial cells. Keratinocytes and mucosal epithelial cells of the stomach as well as the outer epithelial layer of the cornea fail to differentiate properly in the absence of Klf4 (Katz et al., 2005; Segre et al., 1999; Swamynathan et al., 2007). Also, correct cell number and lineage allocation of several cell types depends on Klf4 (Feinberg et al., 2007; Katz et al., 2002; Klaewsongkram et al., 2007). Furthermore, Klf4 has been reported to be an oncogene or tumor suppressor gene, depending on the molecular context in which KLF4 acts (Rowland et al., 2005; Rowland and Peeper, 2006). Indeed, changed Klf4 expression and subcellular localization of KLF4 have been detected in several types of cancers (Evans and Liu, 2008; Foster et al., 2000; Ohnishi et al., 2003) Recently, KLF4 has also been identified as an important factor for reprogramming fibroblasts into a pluripotent state which resembles real embryonic stem cells (Okita et al., 2007a; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Wernig et al., 2007a). Finally, we have shown that KLF4 plays a crucial role in testicular Sertoli cells during postnatal development of the germinal epithelium in mice (Godmann et al., 2008). Due to the implication of KLF4 in these significant biological processes, we hypothesized that KLF4 may be essential for complete spermatogenesis.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Derivation of germ cell-specific Klf4 knockout (gc-Klf4-ko) mice

The gc-Klf4-ko mice were obtained using the Cre/loxP technology. Mice with floxed Klf4 exons 2 to 4 (Godmann et al., 2005) have been described (Klf4loxP/loxP mice; (Katz et al., 2002)). These mice were crossed with a transgenic strain, where the Cre recombinase has been knocked into the locus of the tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) (TNAP+/Cre) (Lomeli et al., 2000). Expression of the Cre recombinase under the control of the TNAP gene promoter occurs already in primordial germ cells (PGC) at E9.5 – 10.5. Since the TNAP locus (MGI ID TNAP: 87983; genome coordinates: 137013809–137068460, 70.2cM, minus strand; http://www.informatics.jax.org) and the Klf4 gene (MGI ID Klf4: 1342287; genome coordinates: 55548243–55553566, 19.7cM, minus strand; http://www.informatics.jax.org) are both located on mouse chromosome 4, mice being heterozygous for the TNAPCre allele and homozygous for the wildtype Klf4 allele (TNAP+/Cre/Klf4+/+) (Lomeli et al., 2000) were at first mated with mice carrying two floxed Klf4 alleles (Katz et al., 2002). Only offspring, where meiotic crossing over resulted in homologous recombination between the TNAPCre/Klf4+ and TNAP+/Klf4loxP loci were used to generate germ cell-specific Klf4 knockout mice: Thus, mice being heterozygous for the TNAPCre locus and carrying one targeted Klf4 allele on that chromosome, which also comprised the TNAPCre locus, were mated with Cre-negative TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/loxP mice. TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko mice are referred to as conditional knockout or mutant mice and TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/ko animals as the corresponding controls. Standard genotyping was performed by multiplex polymerase chain reaction using tail DNA as described below (all primers used in this study are listed in Table 1). Mice studied were on a mixed genetic background. The animals were maintained under controlled conditions of temperature (21°C), light (12L:12D), and 55% humidity with food and water ad libitum. The mice were housed in the central animal facility of the University of Duisburg-Essen Medical School under conditions according to German animal legislation and in accordance with accepted standards of humane animal care. To collect organ and blood samples, mice were anesthetized with Isofluran (CuraMED Pharma, Karlsruhe, Germany) and killed by decapitation.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR.

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence 5′ → 3′ | Application |

|---|---|---|

| β-Act1-fw | acc ttc aac acc ccm gcc atg tac g (m=a/c) | β-Actin, multiplex PCR |

| β-Act2-re | ctr atc cac atc tgc tgg aag gtg g (r=a/g) | |

|

| ||

| Cre26-fw | cct gga aaa tgc ttc tgt ccg | Genotyping |

| Cre36-re | cag ggt gtt ata agc aat ccc | |

|

| ||

| mmKlf4-ex1-fw1 | ctg ggc ccc cac att aat gag | Genotyping |

| mmKlf4-GSP2-re1 | gtc gct gac agc cat gtc aga ctc g | |

| mmKlf4-intr3-re2 | cag agc cgt tct ggc tgt ttt | |

|

| ||

| Actb-fw | agc cat gta cgt agc cat cc | β-Actin, quantitative real-time PCR |

| Actb-re | ctc tca gct gtg gtg gtg aa | |

|

| ||

| Emid2-fw | aca gaa gaa ctg ccc cac ag | Emid2, quantitative real-time PCR |

| Emid2-re | agg gcg tca taa gag acc aa | |

|

| ||

| Klotho-fw | ttt gta gct ggg cac atc c | Klotho, quantitative real-time PCR |

| Klotho-re | ctg gga cac tgg gtt tga g | |

|

| ||

| Svs5-fw1 | gca aga tga gtc cca cca g | Svs5, quantitative real-time PCR |

| Svs5-re1 | gcc gac tga gag aac ctt tc | |

|

| ||

| Tert-fw1 | aga gct ttg ggc aga agg a | Tert, quantitative real-time PCR |

| Tert-re1 | gag cat gct gaa gag agt ctt g | |

|

| ||

| Zfp93-fw1 | aag aga aca atg acc aag tta cag g | Zfp93, quantitative real-time PCR |

| Zfp93-re1 | gct cct cct cgc tga aga c | |

2.2. Serum testosterone

Blood was collected for serum hormone analysis, stored at 4°C overnight and finally centrifuged (20 min, 3000 rpm, 4°C). The serum was stored at − 20°C until assayed. Serum testosterone levels were determined as described (Chandolia et al., 1991). Statistical analyses were performed as described below.

2.3. Tissue processing and immunohistochemistry

Testes were fixed either in Bouin’s solution for 12 hours and paraffin-embedded or embedded in OCT Tissue Tec compound and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Paraffin-embedded specimens were sectioned at 7 μm, re-hydrated and microwaved in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 10 min for antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase was inhibited by incubation with peroxidase blocking reagent (DakoCytomation Carpinteria, CA, USA, LSAB+ system-HRP, K0679). Unspecific binding of the first antibody was blocked by a 30 min incubation step in 0.5% (w/v) BSA in 0.05 mol/L Tris-HCl, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, pH 7.6 (TBS). CREM-1-antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany; X-12; sc-440) was used as primary antibody at a 1:600 dilution. All incubation steps were performed in a humidified chamber and incubation with the primary antibody was performed overnight at 4°C. DakoCytomation Universal LSAB Plus-kit (K0679) including biotinylated second antibody polymer and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated streptavidin was used for detection of bound primary antibody. 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen was used as substrate for the HRP and Mayer’s hematoxylin as counterstain. Control stains were carried out omitting the primary antibody.

Frozen tissues were sectioned at 7 μm. Fixation was performed in 4% Paraformaldehyde/PBS for 20 min at room temperature, followed by 5 min permeabilization in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS. Unspecific binding of the first antibody was blocked by a 30 min incubation step in 5% BSA/0.1% Triton X-100/PBS. Polyclonal anti-KLF4 antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA; AF3158) was used as primary antibody at a 1:100 dilution and incubation was performed over night at 4°C. The primary antibody was detected using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-goat antibody (1:1000; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and applied to the specimens in combination with Phalloidin-TRITC (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) to stain F-Actin. Incubation was done for 1 hour at room temperature. Specimens were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Antibodies were diluted in 5% BSA/0.1% Triton X-100/PBS and all incubation steps were performed in a humidified chamber.

2.4. PCR on genomic DNA - Genotyping

Mice were genotyped as described previously (Godmann et al., 2008). Primer sequences are given in Table 1. Genomic DNA from tail was obtained either by Proteinase K digestion of the tissue in non-ionic detergent (NID) buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris/Cl, pH 8.3, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml gelatin, 0.45% nonidet P40, 0.45% Tween 20), 56°C overnight, followed by Proteinase K heat inactivation (15 min, 95°C) or in case of testis tissue, by using the Qiagen DNeasy Tissue Kit (Hilden, Germany) following the manufacture’s instructions.

2.5. Southern Blotting

Southern blotting was performed according to Matzuk et al. (Matzuk et al., 1992) on testes of adult TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko mutant mice and control mice (TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/ko). To generate a specific Southern blot probe, a 1.8 kb genomic fragment upstream of the Klf4 gene was amplified using the AccuTaq LA DNA polymerase system (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). Primer sequences and PCR conditions for the Klf4 gene were: mmKlf4-SB-fw1 agc gta agt ctg acg tca acg; mmKlf4-SB-re1 gct ctt gga atg cat ctc ttc c; 1× 94°C for 2 min; 35× 94°C for 30 sec, 61°C for 25 sec, 68°C for 2 min; 1× 68°C for 10 min. The PCR product was subcloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), digested with EcoRI and PstI and gel purified. The resulting 668 bp fragment located outside of the original targeting construct, was used as a probe and hybridized to XbaI-digested genomic DNA. A 6.9 kb fragment (representing the floxed Klf4 allele) and a 4.8 kb fragment (Klf4 null allele after homologous recombination) could be detected.

2.6. Protein Isolation and Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted using peqGOLD-TriFast (peqLab Biotechnology GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) following manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amounts of total testis protein from adult (8 weeks old) TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko mutant and TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/ko control mice were resolved by standard SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in PBS that contained 5% low-fat milk, 0.1% Tween-20, and polyclonal goat anti-KLF4 antibody (1:1000, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA; AF3158) or rabbit anti-Actin (1:10000 Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany; A2066) antibody as a loading control. Rabbit anti-goat or goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:20000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) were diluted in 5% milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 and labelling was detected using Amersham ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden). Membranes were exposed to Kodak autoradiography BioMax film.

2.7. RNA Isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using peqGOLD-TriFast (peqLab Biotechnology GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) following manufacturer’s instructions. For oligonucleotide microarray analysis, total RNA was additionally purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA (1μg) was digested with DNase I (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and converted to cDNA with oligo d(T)18 primers using the MuMLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Primers are listed in Table 1.

2.8. Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) reactions were performed in triplicates on 5 mutant samples and 7 control samples, both groups represent eight weeks old, age-matched mice, using an ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) in a total volume of 20 μl containing 40 ng cDNA, 3.75 pmol gene-specific primers and SYBR Green reagent (Applied Biosystems) with ROX as passive control for signal intensity. The thermal cycle profile was 10 sec at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 sec at 95°C and 35 sec at 60°C. Melting curve analysis allowed determination of specificity of the PCR fragments. As an internal standard, each individual sample was normalized to its β-actin (Actb) mRNA content. Primer sequences for Emid2, Zfp93, Svs5, Tert, and Klotho were designed using the Universal ProbeFinder (Roche) and are available in Table 1.

2.9. Microarray analysis

Testes from control mice (TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/ko; n = 4) and testes from mice with a homozygous germ cell-specific deletion of the Klf4 allele (TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko; n = 4) were used for Microarray analysis. All animals were age-matched when they were eight weeks old. Total RNA was extracted and purified as described above. cDNA synthesis and synthesis of biotinylated cRNA were performed as done by Durig et al. (Durig et al., 2003). Each cRNA probe was hybridized to an Affymetrix Gene Chip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, High Wycombe, USA). This Array contains probe sets representing over 39.000 transcripts. For analysis: Using filter criteria of a 2.0 or greater fold change in expression, all “present calls” in at least one group and a p-value of < 0.05 generated from the Mann-Whitney test (equivalent to Wilcoxon rank sum test) produced a list of genes that were differentially expressed. A false discovery rate of 5% was used as a cut off for expressed genes. All genes which showed at least a 2.0-fold change in expression were considered as differentially expressed. Annotation and biological function of these genes were obtained from the NetAffx Analysis Center (Affymetrix), Mouse Genome Informatics (The Jackson Laboratory, http://www.informatics.jax.org/), and Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (http://symatlas.gnf.org/SymAtlas/).

2.10. Promoter analysis

Promoters of KLF4 target genes identified by microarray analysis were analyzed in terms of putative KLF4 binding sites. The CACCC motif was found to be bound by KLF4 and other related transcription factors (Garrett-Sinha et al., 1996; Shields and Yang, 1998). The RRGGYGY (G/AG/AGGC/TGC/T) motif was identified by Shields and Yang (Shields and Yang, 1998). Both sequences are distinct from each other and do not overlap. Moreover, KLF4 appears to have different binding affinities to the described motifs (Shields and Yang, 1998). Both binding sites were used to search the promoters (base pairs − 1000 to − 1 relative to the transcriptional start site) of all genes, which showed at least a 4.0-fold change in expression. Promoter sequences were retrieved using the “Transcriptional Regulatory Element Database” (http://rulai.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/TRED/tred.cgi?process=home) (Jiang et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2005). Further analyses were performed with the Sequencher Software, Gene Codes Cooperation, Ann Arbor, USA.

2.11. Statistical analysis

If not otherwise mentioned, in all experiments presented, a minimum of three control mice (Cre recombinase-negative TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/ko and three germ cell-specific Klf4 knockout mice (TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko) per group have been investigated. Results were expressed as the mean ± SD or mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed by Student’s unpaired t test. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of transgenic mice carrying targeted Klf4 alleles with wild-type mice

Klf4loxP/loxP mice have been used in other studies and no abnormalities of development, cellular function or histology have been reported for Cre-negative Klf4loxP/loxP mice, indicating that the floxed Klf4 allele is functionally wild-type (Feinberg et al., 2007; Godmann et al., 2008; Katz et al., 2005; Klaewsongkram et al., 2007; Swamynathan et al., 2007). Furthermore, we could not detect any differences in testicular histology between wildtype, Cre-negative Klf4loxP/loxP and Cre-negative Klf4loxP/ko mice (data not shown).

3.2. Successful deletion of Klf4 in germ cells

In order to prove genomic recombination between the loxP sites introduced into the Klf4 introns 1 and 4 we performed a genomic Southern blot. We used testicular DNA from adult TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko mutants (n = 3) and functionally heterozygous adult Cre-negative Klf4loxP/ko (n = 3) mice as controls. As shown in Fig. 1a, we detected two bands in the control testes indicating the presence of the floxed allele as well as the mutated allele as expected for the Cre-negative Klf4loxP/ko genotype. Both bands exhibit similar signal intensity. In the mutants, we obtained a strong band representing both, the Klf4 ko allele in all testicular cells and the Cre-loxP-mediated recombined allele in germ cells at 4.8 kb. Very weak signals in mutants at 6.9 kb represent the single non-recombined floxed allele in somatic testicular cells, which represent roughly estimated about 20 % of all testicular cells in the adult testis (estimation based in parts on (Ellis et al., 2004)). This finally results in the ~ 90 : 10 ratio (knockout : loxP) of the Southern blot signals in the ko testes analyzed in this study (Fig. 1a, right lane). Additionally, we performed PCR genotyping on genomic DNA (Fig. 1b). The two rightmost lanes in Fig. 1b show genomic DNA isolated from adult mutant mouse tail and testis. DNA from tail showed two bands representing the recombined ko-allele (ko, upper band in lower panel), which is present in all cells due to our mating strategy, and one band representing the non-recombined loxP allele. Both bands originating from tail DNA exhibit similar signal intensity. This is in sharp contrast to the ratio of loxP : knockout signals found in the testis of the same mutant animal, where almost no loxP band, but a strong band representing the recombined ko allele was detectable. The PCR on genomic tail and testis DNA has been performed under the same conditions. Thus, genomic Southern blotting as well as PCR on genomic DNA indicate extensive recombination of the floxed Klf4-allele in Cre-positive testes. To analyze KLF4 protein levels in mutants and controls, we performed a Western blot analysis using total testis protein extracts isolated from 3 adult (eight weeks old) mice per group (Fig. 1c). The KLF4 signals were normalized to β-Actin. All mutants analyzed exhibited reduced KLF4 protein levels compared to the corresponding controls. To definitively show that spermatids lack KLF4, immunofluorescent localization of KLF4 was performed on cryosections of testes from adult control and mutant animals. Fig. 1d shows that no KLF4 protein could be detected in germ cells of mutant animals while KLF4 is clearly present in spermatids of the control testis (green fluorescence, spermatids denoted by blue arrows in both conditions). Also, interstitial Leydig cells express KLF4 in both conditions (green fluorescence in interstitial compartment, denoted by red arrows). Thus, Klf4 has been successfully deleted from germ cells in the mutant testis.

Figure 1.

Germ cell-specific homologous recombination in testes of adult TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko mice. (a) Genomic Southern blot on DNA isolated from mutant (ko) and control (loxP) testes from adult mice (≥ 8 weeks of age). The 6.9 kb fragment represents the undeleted loxP allele and the 4.8 kb fragment indicates deletion of exons 2, 3, and 4 of the Klf4 gene. In control testes (Cre-negative Klf4loxP/ko) both, the 6.9 kb band and the 4.8 kb can be detected, while TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko animals very predominantly exhibit the small 4.8 kb band. The signal at 6.9 kb representing the loxP allele in Cre-negative somatic cells is only very faint. (b) Genotyping PCR on genomic DNA isolated from tips of tails or testes of Klf4 constitutive knockout mice (null, newborn), adult mutant (ko) and adult control mice (TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/ko (loxP/ko), TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/loxP (loxP/loxP)). The upper band in the upper panel shows β-Actin as an internal control. The lower band in the upper panel shows the presence of the Cre transgene. The lower panel shows Klf4 genotyping. (c) Western blot analysis of KLF4 in testes from 8 weeks old germ cell-specific Klf4 mutants (ko) and age-matched controls (loxP). The mutant testes consistently contain less KLF4 protein than the controls suggesting lack of KLF4 in germ cells. The remaining KLF4 protein in the mutants most likely derives from somatic Leydig cells or Sertoli cells. (d) KLF4 can be detected in spermatids in control testes (loxP) by immunofluorescence (green signal, denoted by blue arrows). In contrast, no KLF4 can be detected in mutant spermatids showing complete absence of Klf4 from spermatids (ko, blue arrows). Interstitial Leydig cells are KLF4-positive in both conditions (green fluorescence, denoted by red arrows). The red staining represents Phalloidin-TRITC labeled F-Actin. Cell nuclei are counter-stained with DAPI and shown in blue.

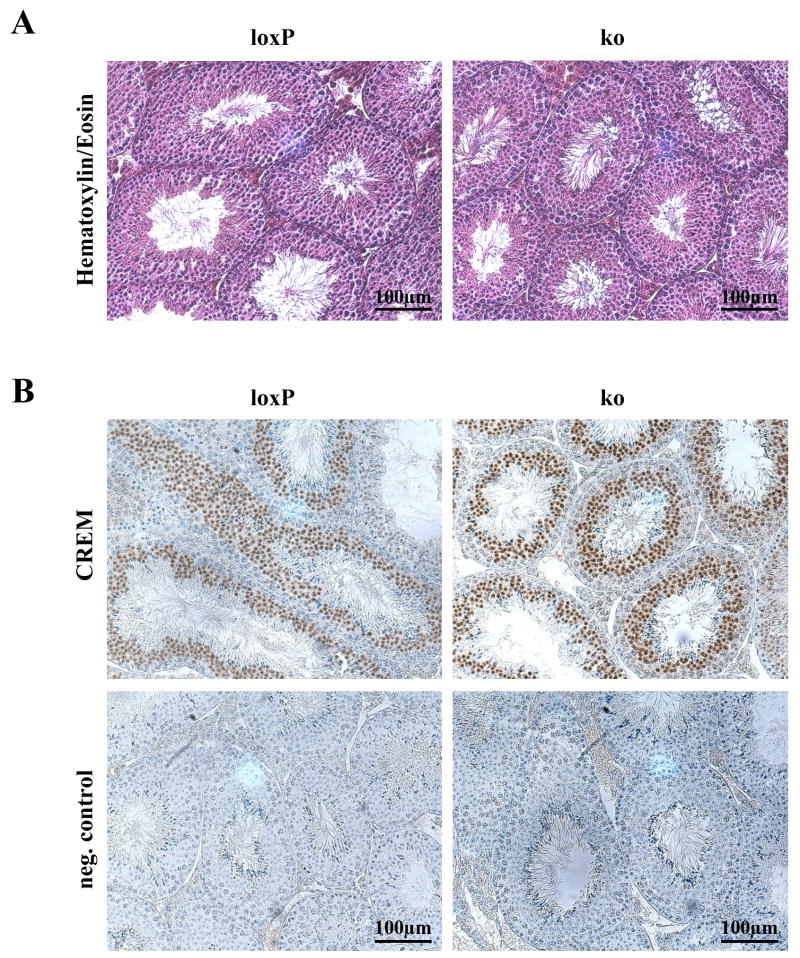

3.3. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Histological analysis was performed on testes of postnatal day 25, 8 weeks, and ≥ 6 month old mutant and control mice (n ≥ 3, per group). No morphological differences could be observed between conditional Klf4 knockout mice at different ages and the corresponding controls. Fig. 2a shows Bouin-fixed and HE-stained paraffin testis sections of 8 weeks old control (n = 4) and mutant mice (n = 4). In both groups spermatogenesis was complete with numerous elongated spermatids at spermatogenic stage VIII (Russell et al., 1990), i.e. the last stage before spermiation. CREM is strongly expressed in round spermatids (Behr et al., 2000; Behr and Weinbauer, 2001) and essential for spermiogenesis (Blendy et al., 1996; Nantel et al., 1996). Since both genes are co-expressed in round spermatids and since we found by TRED analysis (Jiang et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2005) three putative KLF4 binding sites in the Crem promoter (TRED promoter ID 62523; CACCC motif (Garrett-Sinha et al., 1996) at position −261 to −265; RRGGYGY motif (Shields and Yang, 1998) at positions −225 to −231 and −748 to −754), we tested by immunohistochemistry whether the lack of KLF4 influenced CREM expression in spermatids. But there was no difference in CREM expression detectable between both groups. Also, microarray analysis did not reveal any changes in Crem mRNA expression in the mutant testes further supporting that spermiogenesis proceeds normal in KLF4-deficent germ cells (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Testicular histology of adult TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko mice (ko) compared to controls (Cre-negative Klf4loxP/ko; loxP) after fixation in Bouin’s solution and Hematoxylin/Eosin staining. Both genotypes exhibit complete spermatogenesis and numerous elongated spermatids at spermatogenic stage VII/VIII. (b) CREM expression in spermatids is indistinguishable between testes of adult mutant mice (ko) and the corresponding controls (loxP). Brown staining indicates positive reactivity. The sections are counterstained with Hematoxylin. Negative control stains were carried out omitting the primary antibody.

3.4. Testis weight and fertility

Many mutations in genes with importance for testicular function result in reduced testicular weight of mice. In this study, the normal histological appearance of the mutant testes was accompanied by unchanged testis weight of adult (two – six months) mutant animals (n = 7; 231.43 mg ± 36.96 (mean ± SD)) compared to the age-matched controls (n = 8; 232.82 mg ± 29.51 (mean ± SD); p=0.9366). Also, male mice lacking KLF4 in spermatids were fertile and produced fertile offspring. The fertility of ten control breedings (we used those TNAP+/Cre/Klf4+/+ X TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/loxP breedings as controls, where all offspring carried one wildtype Klf4 and one loxP allele showing that no homologues recombination event has occurred between the Klf4 and the TNAP locus) and eleven mutant breedings (TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko × Cre-negative/Klf4loxP/ko) was analyzed over a six month period. Control and mutant breedings showed no differences in numbers of litters and offspring per litter. The pubs of both groups displayed equal ratios with respect to sex and the presence/absence of the Cre transgene. In consideration of our mating strategy and the fact that the constitutive Klf4 knockout leads to early postnatal death (Segre et al., 1999), litter size was reduced due to the expected percentage of Klf4 null mice (25 %). Furthermore, both groups were compared to breedings of TNAP+/+/Klf4+/+ X TNAP+/+/Klf4loxP/loxP animals with respect to the parameters described above. No differences could be observed among all groups, emphasizing that neither the TNAP+/Cre transgene alone nor the floxed Klf4 alleles influenced fertility.

3.5. Serum testosterone levels

Sertoli cell - germ cell interaction is critical for proper function of the germinal epithelium, and spermiogenesis essentially depends on androgen action in Sertoli cells (Holdcraft and Braun, 2004). Male mice with a hypomorphic androgen receptor allele or a Sertoli cell-specific deletion of the AR exhibited impaired terminal differentiation of spermatids (Holdcraft and Braun, 2004) thus providing evidence for an although indirect, yet important functional link between androgen action in Sertoli cells and spermiogenesis. Furthermore, serum testosterone levels in androgen receptor-affected mice were about 40-fold increased. Since most biological processes are regulated via feed back mechanisms, we wondered whether the lack of KLF4 in spermatids could have a possible (indirect) feed back effect on testosterone levels in mutant mice. Therefore, we checked serum testosterone levels in adult male mutant and control animals. However, there were no significant differences between serum testosterone levels in adult mutant (n = 8; 14.81 nmol/l ± 35.19 (mean ± SD)) and corresponding control (n = 10; 16.68 nmol/l ± 18.34 (mean ± SD)) mice (p=0.8861).

3.6. Differentially expressed genes

Since KLF4 is a transcription factor, we were interested in its role in the regulation of gene expression in germ cells. Since it is not exactly known when KLF4 protein exerts its function during spermiogenesis, we analyzed the transcriptome of age-matched, adult (8 weeks old) mutant (n = 4) and control (n = 4) testes. Because spermiogenesis proceeds histologically normal in the Klf4-mutant mice it is unlikely that we identified genes that were differentially expressed due to the lack of a certain cell type, e.g. elongating spermatids, as it is the case for instance in CREM-mutant mice, which exhibit a total block of spermiogenesis at the round spermatid stage (Blendy et al., 1996; Nantel et al., 1996). Thus, it is likely that in the present study we indeed identified genes that were regulated by KLF4 and are not differentially expressed due to the impairment of a certain spermatogenic stage. Using whole genome Affymetrix 430 2.0 microarray chips, we detected 75 probe sets showing statistically significant (p<0.05) two-fold or more down-regulation (Tab. 2). Since KLF4 can function as a transcriptional activator as well as a repressor we also detected 90 probe sets showing up-regulation of genes (Tab. 3). Genomic data were deposited with the NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). To be deleted: (Will immediately be done in case of acceptance of this manuscript according to the journal’s requests and guidelines.)

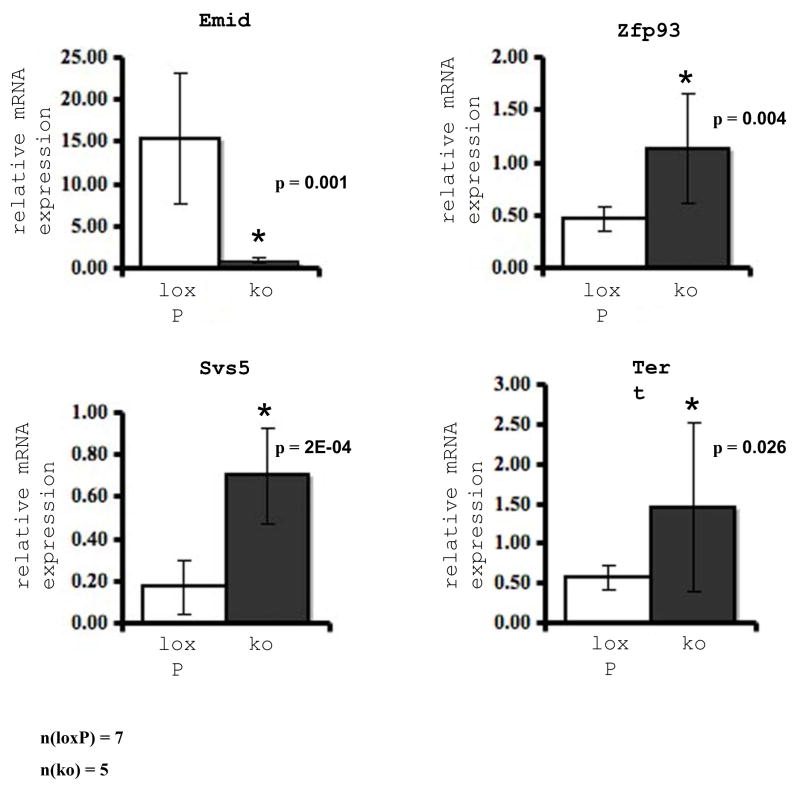

To substantiate the reliability of the microarray screen we also compared expression of a few selected genes in both groups by quantitative real time PCR (Q-PCR). This additional method confirmed differential expression between both groups validating the results of the microarray screen. Q-PCR showed 17-fold reduced steady-state Emid2-mRNA levels in the mutants (microarray: 12.5-fold reduction). We also confirmed by q-PCR increased expression of Svs5 (Seminal vesicle secretion 5; Q-PCR: 4.1-fold increased, Microarray: 9.2-, 3.3-, 2.6-, 2.4-fold increased depending on the probe set), Zfp93 (Zinc finger protein 93; Q-PCR: 2.4-fold increased, Microarray: 2.2-fold increased). We also measured the relative expression levels of Tert (Telomerase reverse transcriptase), which was down-regulated in the mutant testes according to the array data. In contrast, by q-PCR, which is, compared to microarray analysis, the more accurate and reliable method for mRNA quantitation, we found a significant up-regulation (2.6-fold increase, p=0.026) of Tert in the mutant testes. For Klotho, which is also expressed in late spermatids (Li et al., 2004), we were also not able to confirm significant differential expression. To corroborate a direct regulation of the genes identified by microarray analysis by KLF4 we performed an in silico search for known KLF4 binding sites in the promoters of the genes exhibiting strongly different (≥4-up or down-regulated) steady state mRNA levels. Indeed, 25 of the 32 putative promoter sequences which could be retrieved from the TRED database contained between one and 10 potential KLF4 binding sites (Tab. 4).

In order to allocate the identified genes to biological processes with KLF4 involvement, we did an extensive database and literature search (supplementary Table 1). The differentially expressed genes were grouped according to the topics given in Fig. 4. Six out of seven zinc finger transcription factors were up-regulated. In contrast, all five genes in the aberrant expression in cancer-group (depicted are genes that are misregulated in those types of cancers that have been reported to express Klf4 aberrantly as well, e.g. breast, skin, stomach and colon cancer) and all four candidates involved in cell-cell-adhesion were down-regulated. In all other groups, except the small proliferation-group, there were down- as well as up-regulated candidates present. This also includes the large spermatogenesis phenotype-group, which comprises genes whose mutations have a considerable influence on spermatogenesis, as well as the testis expression with unknown function-group. Detailed information on the differentially expressed genes in Fig. 4 including databases and references is provided in supplementary Table 1.

Figure 4.

Differentially expressed genes in adult testes of TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko mice are allocated to biological processes based on NetAffx Analysis Center, Mouse Genome Informatics database (http://www.informatics.jax.org/), and the gene expression SymAtlas (http://symatlas.gnf.org/SymAtlas). Y-axis displays fold change in mRNA expression and bars on X-axis represent differentially expressed genes. Source of information/references are indicated by numbers in brackets. Detailed information is provided in supplementary Tab. 1.

4. Discussion

Krüppel-like factor 4 mRNA is highly expressed in several tissues and cell types including keratinocytes, epithelial cells of the mucosa of the esophagus, stomach and colon and in peripheral blood leukocytes. In these cells KLF4 is critically involved in differentiation and/or the regulation of proliferation (Jiang et al., 2008; Katz et al., 2005; Katz et al., 2002; Li et al., 2005; Segre et al., 1999; Shields et al., 1996). Depending on the molecular context KLF4 has been associated with both tumor suppression as well as tumorigenesis (Rowland et al., 2005; Rowland and Peeper, 2006). Since the constitutive Klf4 knockout is early postnatally lethal, we used the Cre-loxP technique in this study to specifically knockout Klf4 in testicular germ cells, where Klf4 is highly expressed during the postmeiotic differentiation (Behr et al., 2007a; Behr and Kaestner, 2002). Surprisingly, germ cell-specific Klf4 ko mice are fertile and show no abnormalities in testicular histology or testis weight and display no changes in serum testosterone levels. The latter indicates, as rather expected for a germ cell-specific mutation, a non-disturbed hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis. Altogether, our findings in germ cells are in striking contrast to other cell types, where the lack of Klf4 causes severe morphological and functional defects (Feinberg et al., 2007; Katz et al., 2005; Segre et al., 1999; Swamynathan et al., 2007).

This unexpected finding may raise the question whether the deletion of Klf4 in germ cells was complete. Indeed, in a recent publication (Hayashi et al., 2008) the excision of a floxed sequence using the TNAP-Cre mouse, which we also used in the present study, had not occurred in progenitors of ~ 3% of fertilizing spermatozoa in test matings (which in turn may, in case of a positive selection for non-mutated sperm cells in this mating assay, stem from an even smaller population of non-affected spermatogonia). In contrast to this study, Kaneda and colleagues (Kaneda et al., 2004) detected a 100% deletion rate in test matings with male TNAP-Cre mice. Also, the authors demonstrated that PCR-genotyping of germ cells revealed almost completed deletion of the floxed sequence by the newborn stage and complete deletion in adult sperm. Different recombination efficiencies observed in different studies, where the same TNAP-Cre mice have been used, are probably due to the respective floxed genes and not the Cre activity itself (Hayashi et al., 2008; Kaneda et al., 2004; Kehler et al., 2004; Kimura et al., 2003b; Maatouk et al., 2008). Our own data received by genomic Southern blotting as well as by genotyping PCR on testicular genomic DNA shown in Fig. 1 strongly substantiate that recombination in germ cells occurred quantitatively. Moreover, our immunofluorescence data are evidence of complete absence of KLF4 in germ cells, since we never saw any green fluorescent signal representing KLF4 protein expression in mutant spermatids, while heterozygous control spermatids were clearly stained (Fig. 1D). This shows that in the present study the deletion was most likely entire in testicular germ cells.

The TNAP-Cre transgene is already active in primordial germ cells and gonocytes. In case that a primordial germ cell did not undergo Cre-mediated recombination, a whole clone of descended spermatocytes/spermatids (theoretically up to 1024 haploid cells) should have a functional Klf4-allele (Ehmcke et al., 2006). Thus, in case of incomplete Klf4 deletion, it should be expected that in certain clonal areas of the germinal epithelium not only scattered cells expressing low levels of KLF4 should be present. Rather a considerable number of spermatids should be clearly KLF4 positive (comparable to the signal shown in Fig. 1D, left picture, which shows KLF4 signals in Klf4 heterozygous spermatids). We did not detect any group or even single spermatids in mutant testes showing fluorescence that was comparable to that seen in the controls. Therefore, we are convinced that the deletion in our study is complete. A possible explanation for the difference in the efficiency of Cre-mediated recombination (Hayashi et al., 2008; Kaneda et al., 2004) might be the use of different loxP strains.

During spermatogenesis transcription in germ cells is highly orchestrated and follows unique regulatory programs (Eddy, 2002; Hogeveen and Sassone-Corsi, 2006; Kimmins et al., 2004). Using microarray expression analyses we wanted to further unravel the transcriptional network, in which KLF4 is involved in the late stages of male germ cell development. Interestingly our data indicate an increased expression of several zinc-finger proteins belonging to the same family of the Krüppel C2H2-type zinc finger proteins as KLF4. Zfp93 and Zfp618 are both expressed in the testis (GNF SymAtlas; http://symatlas.gnf.org/SymAtlas/) with yet unknown functions. The germ cell-specific Klf4 knockout resulted in an over two times higher expression of Zfp93 and Zfp618 in the mutant testes compared to the controls. Thus it is reasonable to hypothesize that these factors might compensate the lack of KLF4. Recently, Jiang and co-workers described that Klf4 and two other members of the Krüppel-like zinc finger transcription factor family, namely Klf2 and Klf5, are functionally redundant in embryonic stem cells (Jiang et al., 2008). However, in the present study Klf2 and Klf5 expression were not significantly changed in germ cells. Klf4 has been identified as a member of the magic transcription factor quartet being efficiently able to reprogram differentiated cells into pluripotent ones (Okita et al., 2007b; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Wernig et al., 2007b). Interestingly, the maintenance of the undifferentiated ES cell state requires Oct4, Sox2 and c-Myc, but Klf4 is dispensable. Only a triple knockdown of Klf2, Klf4 and Klf5 disrupted self-renewal of ES cells and led to differentiation of the ES cells (Jiang et al., 2008). Also, during iPS cell generation, KLF4 can be efficiently replaced by KLF2 (Nakagawa et al., 2008). Furthermore, in a previous study we also assumed redundancy of Klf4 depletion in testicular Sertoli cells, since only pubertal mutant mice exhibited a disturbance in Sertoli cell differentiation, whereas adult conditional knockout mice were fertile and showed a normal testicular histology (Godmann et al., 2008). Certainly, further experiments need to be done to analyze possible mechanisms in detail that compensate for the loss of Klf4 in male germ cells.

Although there is no evident phenotype with regard to histology and fertility, deletion of Klf4 reveals valuable insights into the transcriptional program of spermatids. Our microarray data identified a huge number of genes, like the most differentially expressed genes in the mutant testes, Emi domain containing 2 (Emi2) and seminal vesicle secretion 5 (Svs5), whose roles in testicular germ cells are as yet unclear. We also found several genes differentially expressed, like germ cell-less homolog (Drosophila) (Kimura et al., 2003a), whose function in sperm cells is at least partially characterized. Further interesting genes, which are differentially expressed and which may provide further clues to understand the function of KLF4 in spermatids, include the spermatid-expressed zinc finger protein (Zfp) 93 (Behr et al., 2007b; Shannon et al., 1996; Shannon and Stubbs, 1998), Sox7, Bach2 (Ochiai et al., 2006; Ochiai et al., 2008) (Wang et al., 2008), and Kif17b (Fimia et al., 1999; Macho et al., 2002). However, although we identified many differentially expressed genes in this study, spermiogenesis appears to be a cell biological process, which is, compared to the function of other cell types lacking Klf4, quite well safeguarded against the lack of Klf4.

The TNAP gene promoter activates Cre expression in the mouse line used in this study already in primordial germ cells (Lomeli et al., 2000) and there is no reason to query that recombination of the Klf4loxP gene already occurred at that early stage during germ cell development. It has recently been shown by Western blot analysis that KLF4 is already expressed in so-called germ line stem cells (Kanatsu-Shinohara et al., 2008), which are basically cultured spermatogonial stem cells which retain their spermatogonial stem cell identity in culture over long periods of time (Kanatsu-Shinohara et al., 2004). We have very recently shown that certain types of human testicular germ cell tumors, namely intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified and seminoma (formerly carcinoma in situ), which most likely derive from gonocytes (Rajpert-De Meyts, 2006), strongly express KLF4 (Godmann et al, 2009). This is in contrast to most tumors, in which KLF4 is down-regulated. Sporadically, we also detected KLF4 in human gonocytes (Godmann et al., 2009), while we were unable to detect KLF4 immunohistochemically in most human gonocyte samples and generally in monkey and mouse gonocytes. These findings shed an interesting light on the fact that the present screen for differentially expressed genes in Klf4-mutant germ cells identified some factors that are known to be expressed in testicular or other types of stem cells or even germ cell tumors. These factors include SFRP1, which is a soluble WNT antagonist (Bafico et al., 1999) and known to be overexpressed in intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified (carcinoma in situ) samples and in teratoma (Hoei-Hansen et al., 2004), the telomerase reverse transcriptase Tert (Ravindranath et al., 1997), and Runx1, which is expressed in haematopoietic and hair follicle stem cells and has essential functions in these adult stem cell types (Cai et al., 2000; Osorio et al., 2008). Thus, we speculate that KLF4 does not only regulate postmeiotic but also gonocyte/spermatogonial gene expression. We therefore hypothesize that KLF4 activity (in concert with other KLFs or zinc finger transcription factors) may play significant roles not only in pluripotent stem cells (Jiang et al., 2008; Li et al., 2005; Okita et al., 2007b; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Wernig et al., 2007b) but also in testicular stem cells.

Altogether, we provided evidence that the deletion of Klf4 in male mouse germ cells affects the postmeiotic transcriptome including defined transcriptional regulators. Thereby, these data will help to unravel the transcriptional networks and hierarchies controlling spermatid development. However, the microarray data did not reveal a specific biological process or signal transduction pathways that might be controlled by KLF4. In fact, the effects of KLF4 on the transcriptional program of testicular germ cells appear to be rather pleiotropic. Moreover, it is likely, that the function of KLF4 is redundant with other Krüppel-like factors or even other closely related zinc finger transcription factors, so that simultaneous deletion of two or more factors is needed to demonstrate the function of KLF activity in germ cells. Surprisingly, we also provide clues for an additional role of KLF4 in spermatogonial stem cell regulation. However, to corroborate this hypothesis further detailed studies on this special cell type are necessary. In summary, the lack of KLF4 alone in male germ cells unexpectedly does not prevent spermiogenesis and male fertility.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA expression levels of selected genes revealed by quantitative real time-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from whole testis of eight weeks old, age-matched mutant (TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko; n = 5) (ko, grey bars) and control (Cre-negative Klf4loxP/ko; n = 7) (loxP, white bars) mice. Each reaction was done in triplicate for each gene. Data represent means ± SEM and are shown as relative mRNA expression after normalization to β-Actin. (a) Emid2 exhibits 17.4 fold decreased expression in testes of mutant mice (ko) (p = 0.001). (b) Svs5 is 4.1-fold increased in mutants (ko) (p = 2E-04). (c) Zfp93 is 2.4-fold increased in mutants (ko) (p = 0.004). (d) Tert exhibits 2.6-fold increased expression in mutants (ko) (p = 0.026). These data confirm the microarray results (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Annotated genes significantly down-regulated in 8 weeks old germ cell-specific Klf4-mutant testes (TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko) compared to age-matched controls (Cre-neg./Klf4loxP/ko).

| Probe Set ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Change | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1425310_a_at | EMI domain containing 2 | Emid2 | 12,5 | 0,014 |

| 1421741_at | cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily a, polypeptide 16 | Cyp3a16 | 11,905 | 0,014 |

| 1448974_at | Doublecortin | Dcx | 9,901 | 0,014 |

| 1439941_at | similar to H3 histone, family 3B | LOC435263 | 9,615 | 0,014 |

| 1427778_at | defensin beta 8 | Defb8 | 6,623 | 0,014 |

| 1452295_at | transmembrane, prostate androgen induced RNA | Tmepai | 6,369 | 0,014 |

| 1420344_x_at | granzyme D | Gzmd | 5,952 | 0,043 |

| 1427738_at | DNA segment, KIST 2 | D0Kist2 | 5,155 | 0,014 |

| 1451386_at | biliverdin reductase B (flavin reductase (NADPH)) | Blvrb | 5,076 | 0,014 |

| 1442236_at | zinc finger, A20 domain containing 3 | Za20d3 | 4,808 | 0,014 |

| 1425748_at | DIRAS family, GTP-binding RAS-like 1 | Diras1 | 4,673 | 0,014 |

| 1419723_at | opsin 1 (cone pigments), medium-wave-sensitive (color blindness, deutan) | Opn1mw | 4,608 | 0,043 |

| 1456049_at | v-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog A (ras related) | Rala | 4,505 | 0,043 |

| 1451620_at | C1q-like 3 | C1ql3 | 4,444 | 0,043 |

| 1437915_at | target of myb1-like 2 (chicken) | Tom1l2 | 4,082 | 0,014 |

| 1430643_at | mutS homolog 3 (E. coli) | Msh3 | 4,065 | 0,014 |

| 1418555_x_at | Spi-C transcription factor (Spi-1/PU.1 related) | Spic | 4,032 | 0,014 |

| 1447280_at | Dystrobrevin alpha (Dtna), transcript variant 2, mRNA | Dtna | 3,311 | 0,043 |

| 1437340_x_at | gastrokine 1 | Gkn1 | 3,257 | 0,043 |

| 1421449_at | CUB and Sushi multiple domains 1 | Csmd1 | 3,185 | 0,043 |

| 1440777_x_at | prostaglandin F receptor | Ptgfr | 3,155 | 0,014 |

| 1425437_a_at | potassium channel, subfamily K, member 7 | Kcnk7 | 3,067 | 0,014 |

| 1420490_at | kallikrein 16 | Klk16 | 3,058 | 0,014 |

| 1432495_at | SRY-box containing gene 7 | Sox7 | 3,030 | 0,014 |

| 1420431_at | Repetin | Rptn | 2,985 | 0,043 |

| 1443276_at | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 5A (Htr5a), mRNA | Htr5a | 2,899 | 0,014 |

| 1420648_at | tripartite motif protein 12 | Trim12 | 2,890 | 0,043 |

| 1443250_at | regulator of G-protein signaling 2 | Rgs2 | 2,817 | 0,043 |

| 1455650_at | Serine/arginine-rich protein specific kinase 2, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:27638 IMAGE:4507346) | Srpk2 | 2,809 | 0,014 |

| 1426045_at | kininogen 1 | Kng1 | 2,770 | 0,014 |

| 1422135_at | zinc finger protein 146 | Zfp146 | 2,739 | 0,014 |

| 1438956_x_at | proviral integration site 3 | Pim3 | 2,653 | 0,014 |

| 1451892_at | klotho | Kl | 2,597 | 0,014 |

| 1423581_at | N-myristoyltransferase 2 | Nmt2 | 2,597 | 0,014 |

| 1420797_at | otogelin | Otog | 2,532 | 0,043 |

| 1439435_x_at | phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | Pgk1 | 2,451 | 0,014 |

| 1451501_a_at | growth hormone receptor | Ghr | 2,439 | 0,014 |

| 1425582_a_at | endomucin | MGI:1891716 | 2,336 | 0,014 |

| 1417978_at | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E member 3 | Eif4e3 | 2,278 | 0,014 |

| 1437685_x_at | fibromodulin | Fmod | 2,237 | 0,014 |

| 1421661_at | formyl peptide receptor-like 1 | Fprl1 | 2,237 | 0,014 |

| 1448023_at | kalirin, RhoGEF kinase | Kalrn | 2,179 | 0,014 |

| 1423396_at | angiotensinogen (serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 8) | Agt | 2,179 | 0,014 |

| 1421671_at | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 3 | Hsd17b3 | 2,137 | 0,014 |

| 1418086_at | protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 14A | Ppp1r14a | 2,132 | 0,014 |

| 1436577_at | Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 9 | Arhgef9 | 2,128 | 0,043 |

| 1448222_x_at | cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIIIa | Cox8a | 2,092 | 0,043 |

| 1454696_at | guanine nucleotide binding protein, beta 1 | Gnb1 | 2,083 | 0,014 |

Table 3.

Annotated genes significantly up-regulated in 8 weeks old germ cell-specific Klf4-mutant testes (TNAP+/Cre/Klf4loxP/ko) compared to age-matched controls (Cre-neg./Klf4loxP/ko).

| Probe Set ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Change | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1427220_a_at | seminal vesicle secretion 5 | Svs5 | 9,15 | 0,014 |

| 1460300_a_at | leukocyte tyrosine kinase | Ltk | 8,082 | 0,014 |

| 1419388_at | transmembrane 4 L six family member 20 | Tm4sf20 | 7,146 | 0,014 |

| 1459136_at | BTB and CNC homology 2 (Bach2), mRNA | Bach2 | 6,871 | 0,014 |

| 1441937_s_at | PTEN induced putative kinase 1 | Pink1 | 6,434 | 0,014 |

| 1459481_at | Protocadherin (PCDHX gene) | Pcdh11x | 6,106 | 0,014 |

| 1426851_a_at | nephroblastoma overexpressed gene | Nov | 5,648 | 0,014 |

| 1419826_at | kinesin family member 17 | Kif17 | 5,621 | 0,014 |

| 1438617_at | Thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) | Serpina7 | 5,344 | 0,014 |

| 1418951_at | taxilin beta | Txlnb | 5,213 | 0,014 |

| 1455869_at | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, beta (Camk2b), mRNA | Camk2b | 3,436 | 0,043 |

| 1422242_at | defensin related cryptdin, related sequence 10 | Defcr-rs10 | 3,331 | 0,014 |

| 1416594_at | secreted frizzled-related sequence protein 1 | Sfrp1 | 3,3 | 0,014 |

| 1419346_a_at | seminal vesicle secretion 5 | Svs5 | 3,296 | 0,043 |

| 1432467_at | leucine-rich repeats and calponin homology (CH) domain containing 3 | Lrch3 | 3,282 | 0,014 |

| 1422856_at | solute carrier family 12, member 3 | Slc12a3 | 3,113 | 0,043 |

| 1438806_at | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 9-like | Bcl9l | 3,013 | 0,014 |

| 1439422_a_at | C1q domain containing 2 | C1qdc2 | 2,907 | 0,014 |

| 1422588_at | keratin complex 2, basic, gene 6b | Krt2–6b | 2,864 | 0,043 |

| 1448254_at | Pleiotrophin | Ptn | 2,844 | 0,014 |

| 1435760_at | cystatin A///similar to Stefin homolog | MGI:3524930///LOC547252 | 2,789 | 0,043 |

| 1427772_at | defensin beta 15 | Defb15 | 2,778 | 0,043 |

| 1454292_at | germ cell-less homolog (Drosophila) | Gcl | 2,666 | 0,043 |

| 1438950_x_at | resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8 homolog (C. elegans) | Ric8 | 2,663 | 0,014 |

| 1425829_a_at | STEAP family member 4 | Steap4 | 2,611 | 0,014 |

| 1422864_at | runt related transcription factor 1 | Runx1 | 2,609 | 0,043 |

| 1419347_x_at | seminal vesicle secretion 5 | Svs5 | 2,577 | 0,014 |

| 1440571_at | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma, 3, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5321197) | Eif4g3 | 2,54 | 0,043 |

| 1416166_a_at | peroxiredoxin 4 | Prdx4 | 2,534 | 0,014 |

| 1443677_at | Zinc finger and BTB domain containing 38 (Zbtb38), mRNA | A930014K01Rik | 2,522 | 0,014 |

| 1419109_at | histidine rich calcium binding protein | Hrc | 2,485 | 0,014 |

| 1439356_at | flightless I homolog (Drosophila) | Fliih | 2,473 | 0,014 |

| 1422716_a_at | acid phosphatase 1, soluble | Acp1 | 2,397 | 0,043 |

| 1456124_x_at | seminal vesicle secretion 5 | Svs5 | 2,389 | 0,014 |

| 1428474_at | protein phosphatase 3, catalytic subunit, beta isoform | Ppp3cb | 2,374 | 0,014 |

| 1421589_at | keratin complex 1, acidic, gene 1 PREDICTED: Mus musculus similar to BDNF/NT-3 growth factors |

Krt1-1 | 2,356 | 0,014 |

| 1444121_at | receptor precursor (Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor type 2) (TrkB tyrosine kinase) (GP145-TrkB/GP95-TrkB) (Trk-B) (LOC544937), mRNA | 2,356 | 0,043 | |

| 1443746_x_at | dentin matrix protein 1 | Dmp1 | 2,309 | 0,014 |

| 1444246_at | chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 2 | Chd2 | 2,301 | 0,014 |

| 1440511_at | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) activator subunit 4, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:4987120) | Psme4 | 2,286 | 0,014 |

| 1460368_at | membrane protein, palmitoylated 4 (MAGUK p55 subfamily member 4) | Mpp4 | 2,255 | 0,043 |

| 1420080_a_at | glutamine fructose-6-phosphate transaminase 1 | Gfpt1 | 2,24 | 0,014 |

| 1441404_at | Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase, isoform 1b, beta1 subunit, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:13913 IMAGE:4017963) | Pafah1b1 | 2,211 | 0,014 |

| 1425315_at | dedicator of cytokinesis 7 | Dock7 | 2,211 | 0,043 |

| 1441876_x_at | Zinc finger protein 93, mRNA (cDNA clone MGC:5985 IMAGE:3496816) | Zfp93 | 2,194 | 0,014 |

| 1453247_at | zinc fingerprotein 618 | Zfp618 | 2,187 | 0,043 |

| 1443909_at | Cleavage stimulation factor, 3′ pre-RNA, subunit 3 (Cstf3), mRNA | Cstf3 | 2,164 | 0,014 |

| 1451916_s_at | tripartite motif protein 15 | Trim15 | 2,114 | 0,043 |

| 1437620_x_at | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1 (Aldh18a1), transcript variant 2, mRNA | Pycs | 2,11 | 0,014 |

| 1439631_at | zinc finger, CCHC domain containing 11 | Zcchc11 | 2,104 | 0,043 |

| 1424448_at | tripartite motif protein 6 | Trim6 | 2,097 | 0,043 |

| 1428586_at | transmembrane protein 41B | Tmem41b | 2,073 | 0,014 |

| 1425393_a_at | mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 7 | Map2k7 | 2,056 | 0,043 |

| 1440455_at | expressed sequence AI848599 | AI848599 | 2,053 | 0,014 |

| 1439618_at | phosphodiesterase 10A | Pde10a | 2,038 | 0,014 |

| 1455938_x_at | RAD21 homolog (S. pombe) | Rad21 | 2,017 | 0,043 |

| 1431617_at | RIKEN cDNA 4933405E24 gene | 4933405E24Rik | 2,011 | 0,014 |

| 1451527_at | procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer 2 | Pcolce2 | 2,003 | 0,043 |

| 1457249_at | Ubiquitin associated protein 2-like (Ubap2l), transcript variant 2, mRNA | Ubap2l | 2,001 | 0,043 |

Table 4.

Numbers and positions of KLF4 binding sites in the promoters of KLF4 target genes.

| Probe set ID | Transcript ID | Gene symbol | Promoter ID (TRED) | BS total number | Start position of BS: RRGGYGY (R = G or A); (Y = C or T) (Shields and Yang 1998) | Start position of BS: CACCC (Garrett-Sinha 1996) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1427220_a_at | NM_009301 | Svs5 | 65145 | 2 | −424; −412 | |

| 1460300_a_at | NM_008523 | Ltk | 66088 | 5 | −775; −391; −315; −172 | −106 |

| 1419388_at | NM_025453 | Tm4sf20 | 46814 | none | ||

| 126070 | none | |||||

| 1459136_at | NM_007521 | Bach2 | 68993 | 3 | −438; −311 | −341 |

| 1441937_s_at | NM_026880 | Pink1 | 70430 | 2 | −902; −490 | |

| 1426851_a_at | NM_010930 | Nov | 57002 | 5 | −369 | −549; −326; −135; −117 |

| 1419826_at | NM_010623 | Kif17 | 69829 | 4 | −812; −30; −9 | −367 |

| 1418951_at | NM_138628 | Txlnb | 47317 | 3 | −948; −920; −759 | |

| 1425310_a_at | NM_024474 | Emid2 | 72893 | 3 | −782; −15 | −179 |

| 1421741_at | NM_007820 | Cyp3a16 | 129983 | 2 | −684 | −401 |

| 72750 | 2 | −298 | −77 | |||

| 1448974_at | NM_010025 | Dcx | 84245 | 3 | −700 | −630; −522 |

| 1427778_at | NM_019728 | Defb8 | 81139 | 2 | −125 | −842 |

| 1452295_at | NM_022995 | Tmepai | 65471 | 8 | −984; −889; −881; −786; −683; | |

| −578; −560; −490 | ||||||

| 1420344_x_at | NM_010372 | Gzmd | 127419 | 1 | −83 | |

| 56477 | 2 | −681; −115 | ||||

| 1451386_at | NM_144923 | Blvrb | 76371 | 2 | −881; −823 | |

| 76372 | 10 | −788; −281; −136; −45 | −685; −668; −582; −489; | |||

| −357; −348 | ||||||

| 1425748_at | NM_145217 | Diras1 | 48570 | 7 | −711; −570; −566; −471; | |

| −231; −153; −32 | ||||||

| 1419723_at | NM_008106 | Opn1mw | 83743 | 2 | −730; −167 | |

| 1456049_at | NM_019491 | Rala | 55414 | none | ||

| 55415 | none | |||||

| 136376 | none | |||||

| 1451620_at | NM_153155 | C1ql3 | 66949 | 1 | −163 | |

| 1437915_at | NM_001039093 | Tom1l2 | 51969 | 1 | −65 | |

| 1430643_at | NM_010829 | Msh3 | 54891 | 1 | −614 | |

| 1418555_x_at | NM_011461 | Spic | 126423 | none | ||

| 48494 | 1 | −13 |

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support of Dr. R. Renkawitz-Pohl, University of Marburg, and Dr. H.-W. Denker, Institute of Anatomy, University of Duisburg-Essen. We thank Dr. Ludger Klein-Hitpass, BioChip Laboratory, University of Duisburg-Essen, Medical School for performing microarray hybridization and statistical analyses, and I. Kromberg, D. Schünke, and R. Sandhowe-Klaverkamp for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Be 2296/4) to RB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bafico A, Gazit A, Pramila T, Finch PW, Yaniv A, Aaronson SA. Interaction of frizzled related protein (FRP) with Wnt ligands and the frizzled receptor suggests alternative mechanisms for FRP inhibition of Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16180–16187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr R, Deller C, Godmann M, Muller T, Bergmann M, Ivell R, Steger K. Kruppel-like factor 4 expression in normal and pathological human testes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007a;13:815–820. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr R, Hunt N, Ivell R, Wessels J, Weinbauer GF. Cloning and expression analysis of testis-specific cyclic 3′, 5′-adenosine monophosphate-responsive element modulator activators in the nonhuman primate (Macaca fascicularis): comparison with other primate and rodent species. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1344–1351. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.5.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr R, Kaestner KH. Developmental and cell type-specific expression of the zinc finger transcription factor Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) in postnatal mouse testis. Mech Dev. 2002;115:167–169. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr R, Sackett SD, Bochkis IM, Le PP, Kaestner KH. Impaired male fertility and atrophy of seminiferous tubules caused by haploinsufficiency for Foxa3. Dev Biol. 2007b;306:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr R, Weinbauer GF. cAMP response element modulator (CREM): an essential factor for spermatogenesis in primates? Int J Androl. 2001;24:126–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2001.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissbarth T, Borisevich I, Horlein A, Kenzelmann M, Hergenhahn M, Klewe-Nebenius A, Klaren R, Korn B, Schmid W, Vingron M, Schutz G. Analysis of CREM-dependent gene expression during mouse spermatogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;212:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendy JA, Kaestner KH, Weinbauer GF, Nieschlag E, Schutz G. Severe impairment of spermatogenesis in mice lacking the CREM gene. Nature. 1996;380:162–165. doi: 10.1038/380162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, de Bruijn M, Ma X, Dortland B, Luteijn T, Downing RJ, Dzierzak E. Haploinsufficiency of AML1 affects the temporal and spatial generation of hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse embryo. Immunity. 2000;13:423431. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandolia RK, Weinbauer GF, Simoni M, Behre HM, Nieschlag E. Comparative effects of chronic administration of the non-steroidal antiandrogens flutamide and Casodex on the reproductive system of the adult male rat. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1991;125:547–555. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1250547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durig J, Nuckel H, Huttmann A, Kruse E, Holter T, Halfmeyer K, Fuhrer A, Rudolph R, Kalhori N, Nusch A, Deaglio S, Malavasi F, Moroy T, Klein-Hitpass L, Duhrsen U. Expression of ribosomal and translation-associated genes is correlated with a favorable clinical course in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:2748–2755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy EM. Male germ cell gene expression. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:103–128. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehmcke J, Wistuba J, Schlatt S. Spermatogonial stem cells: questions, models and perspectives. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:275–282. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmk001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis PJ, Furlong RA, Wilson A, Morris S, Carter D, Oliver G, Print C, Burgoyne PS, Loveland KL, Affara NA. Modulation of the mouse testis transcriptome during postnatal development and in selected models of male infertility. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:271–281. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans PM, Liu C. Roles of Krupel-like factor 4 in normal homeostasis, cancer and stem cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008;40:554–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg MW, Wara AK, Cao Z, Lebedeva MA, Rosenbauer F, Iwasaki H, Hirai H, Katz JP, Haspel RL, Gray S, Akashi K, Segre J, Kaestner KH, Tenen DG, Jain MK. The Kruppel-like factor KLF4 is a critical regulator of monocyte differentiation. Embo J. 2007;26:4138–4148. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimia GM, De Cesare D, Sassone-Corsi P. CBP-independent activation of CREM and CREB by the LIM-only protein ACT. Nature. 1999;398:165–169. doi: 10.1038/18237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KW, Frost AR, McKie-Bell P, Lin CY, Engler JA, Grizzle WE, Ruppert JM. Increase of GKLF messenger RNA and protein expression during progression of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6488–6495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett-Sinha LA, Eberspaecher H, Seldin MF, de Crombrugghe B. A gene for a novel zinc-finger protein expressed in differentiated epithelial cells and transiently in certain mesenchymal cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31384–31390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godmann M, Katz JP, Guillou F, Simoni M, Kaestner KH, Behr R. Kruppel-like factor 4 is involved in functional differentiation of testicular Sertoli cells. Dev Biol. 2008;315:552–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godmann M, Kromberg I, Mayer J, Behr R. The mouse Kruppel-like Factor 4 (Klf4) gene: four functional polyadenylation sites which are used in a cell-specific manner as revealed by testicular transcript analysis and multiple processed pseudogenes. Gene. 2005;361:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Kaneda M, Tang F, Hajkova P, Lao K, O’Carroll D, Das PP, Tarakhovsky A, Miska EA, Surani MA. MicroRNA biogenesis is required for mouse primordial germ cell development and spermatogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoei-Hansen CE, Nielsen JE, Almstrup K, Hansen MA, Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-DeMeyts E, Leffers H. Identification of genes differentially expressed in testes containing carcinoma in situ. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:423–431. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogeveen KN, Sassone-Corsi P. Regulation of gene expression in post-meiotic male germ cells: CREM-signalling pathways and male fertility. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2006;9:73–79. doi: 10.1080/14647270500463400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdcraft RW, Braun RE. Androgen receptor function is required in Sertoli cells for the terminal differentiation of haploid spermatids. Development. 2004;131:459–467. doi: 10.1242/dev.00957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Xuan Z, Zhao F, Zhang MQ. TRED: a transcriptional regulatory element database, new entries and other development. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D137–140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Chan YS, Loh YH, Cai J, Tong GQ, Lim CA, Robson P, Zhong S, Ng HH. A core Klf circuitry regulates self-renewal of embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:353–360. doi: 10.1038/ncb1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Inoue K, Lee J, Yoshimoto M, Ogonuki N, Miki H, Baba S, Kato T, Kazuki Y, Toyokuni S, Toyoshima M, Niwa O, Oshimura M, Heike T, Nakahata T, Ishino F, Ogura A, Shinohara T. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from neonatal mouse testis. Cell. 2004;119:1001–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Lee J, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Miki H, Toyokuni S, Ikawa M, Nakamura T, Ogura A, Shinohara T. Pluripotency of a single spermatogonial stem cell in mice. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:681–687. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda M, Okano M, Hata K, Sado T, Tsujimoto N, Li E, Sasaki H. Essential role for de novo DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a in paternal and maternal imprinting. Nature. 2004;429:900–903. doi: 10.1038/nature02633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JP, Perreault N, Goldstein BG, Actman L, McNally SR, Silberg DG, Furth EE, Kaestner KH. Loss of Klf4 in mice causes altered proliferation and differentiation and precancerous changes in the adult stomach. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:935–945. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JP, Perreault N, Goldstein BG, Lee CS, Labosky PA, Yang VW, Kaestner KH. The zinc-finger transcription factor Klf4 is required for terminal differentiation of goblet cells in the colon. Development. 2002;129:2619–2628. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehler J, Tolkunova E, Koschorz B, Pesce M, Gentile L, Boiani M, Lomeli H, Nagy A, McLaughlin KJ, Scholer HR, Tomilin A. Oct4 is required for primordial germ cell survival. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmins S, Kotaja N, Davidson I, Sassone-Corsi P. Testis-specific transcription mechanisms promoting male germ-cell differentiation. Reproduction. 2004;128:5–12. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Ito C, Watanabe S, Takahashi T, Ikawa M, Yomogida K, Fujita Y, Ikeuchi M, Asada N, Matsumiya K, Okuyama A, Okabe M, Toshimori K, Nakano T. Mouse germ cell-less as an essential component for nuclear integrity. Mol Cell Biol. 2003a;23:1304–1315. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1304-1315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Suzuki A, Fujita Y, Yomogida K, Lomeli H, Asada N, Ikeuchi M, Nagy A, Mak TW, Nakano T. Conditional loss of PTEN leads to testicular teratoma and enhances embryonic germ cell production. Development. 2003b;130:1691–1700. doi: 10.1242/dev.00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaewsongkram J, Yang Y, Golech S, Katz J, Kaestner KH, Weng NP. Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates B cell number and activation-induced B cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2007;179:4679–4684. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SA, Watanabe M, Yamada H, Nagai A, Kinuta M, Takei K. Immunohistochemical localization of Klotho protein in brain, kidney, and reproductive organs of mice. Cell Struct Funct. 2004;29:91–99. doi: 10.1247/csf.29.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, McClintick J, Zhong L, Edenberg HJ, Yoder MC, Chan RJ. Murine embryonic stem cell differentiation is promoted by SOCS-3 and inhibited by the zinc finger transcription factor Klf4. Blood. 2005;105:635–637. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomeli H, Ramos-Mejia V, Gertsenstein M, Lobe CG, Nagy A. Targeted insertion of Cre recombinase into the TNAP gene: excision in primordial germ cells. Genesis. 2000;26:116–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maatouk DM, Loveland KL, McManus MT, Moore K, Harfe BD. Dicer1 is required for differentiation of the mouse male germline. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:696–703. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.067827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho B, Brancorsini S, Fimia GM, Setou M, Hirokawa N, Sassone-Corsi P. CREM-dependent transcription in male germ cells controlled by a kinesin. Science. 2002;298:2388–2390. doi: 10.1126/science.1077265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Bradley A. Alpha-inhibin is a tumour-suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature. 1992;360:313–319. doi: 10.1038/360313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantel F, Monaco L, Foulkes NS, Masquilier D, LeMeur M, Henriksen K, Dierich A, Parvinen M, Sassone-Corsi P. Spermiogenesis deficiency and germ-cell apoptosis in CREM-mutant mice. Nature. 1996;380:159–162. doi: 10.1038/380159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai K, Katoh Y, Ikura T, Hoshikawa Y, Noda T, Karasuyama H, Tashiro S, Muto A, Igarashi K. Plasmacytic transcription factor Blimp-1 is repressed by Bach2 in B cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38226–38234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai K, Muto A, Tanaka H, Takahashi S, Igarashi K. Regulation of the plasma cell transcription factor Blimp-1 gene by Bach2 and Bcl6. Int Immunol. 2008;20:453–460. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi S, Ohnami S, Laub F, Aoki K, Suzuki K, Kanai Y, Haga K, Asaka M, Ramirez F, Yoshida T. Downregulation and growth inhibitory effect of epithelial-type Kruppel-like transcription factor KLF4, but not KLF5, in bladder cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:251–256. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007a;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio KM, Lee SE, McDermitt DJ, Waghmare SK, Zhang YV, Woo HN, Tumbar T. Runx1 modulates developmental, but not injury-driven, hair follicle stem cell activation. Development. 2008;135:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.012799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindranath N, Dalal R, Solomon B, Djakiew D, Dym M. Loss of telomerase activity during male germ cell differentiation. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4026–4029. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland BD, Bernards R, Peeper DS. The KLF4 tumour suppressor is a transcriptional repressor of p53 that acts as a context-dependent oncogene. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1074–1082. doi: 10.1038/ncb1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland BD, Peeper DS. KLF4, p21 and context-dependent opposing forces in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LD, Ettlin RA, Sinha Hikim AP, Clegg ED. Histological and Histopathological Evaluation of the Testis. Cache River Press; Clearwater, Florida: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sassone-Corsi P. CREM: a master-switch governing male germ cells differentiation and apoptosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:475–482. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre JA, Bauer C, Fuchs E. Klf4 is a transcription factor required for establishing the barrier function of the skin. Nat Genet. 1999;22:356–360. doi: 10.1038/11926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon M, Ashworth LK, Mucenski ML, Lamerdin JE, Branscomb E, Stubbs L. Comparative analysis of a conserved zinc finger gene cluster on human chromosome 19q and mouse chromosome 7. Genomics. 1996;33:112–120. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon M, Stubbs L. Analysis of homologous XRCC1-linked zinc-finger gene families in human and mouse: evidence for orthologous genes. Genomics. 1998;49:112–121. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JM, Christy RJ, Yang VW. Identification and characterization of a gene encoding a gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor expressed during growth arrest. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20009–20017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JM, Yang VW. Identification of the DNA sequence that interacts with the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:796–802. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.3.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamynathan SK, Katz JP, Kaestner KH, Ashery-Padan R, Crawford MA, Piatigorsky J. Conditional deletion of the mouse Klf4 gene results in corneal epithelial fragility, stromal edema, and loss of conjunctival goblet cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:182–194. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00846-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Zhuang L, Gao B, Shi CX, Cheung J, Liu M, Jin T, Wen XY. The Blimp-1 gene regulatory region directs EGFP expression in multiple hematopoietic lineages and testis in mice. Transgenic Res. 2008;17:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007a;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Xuan Z, Liu L, Zhang MQ. TRED: a Transcriptional Regulatory Element Database and a platform for in silico gene regulation studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D103–107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.