Abstract

Although the glycocalyx has been implicated in wall shear stress (WSS) mechanotransduction, the role of glycocalyx components in nitric oxide (NO*) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production remains unclear. Here, we tested the hypothesis that glycocalyx is implicated in both endothelial NO* and O2- production. Specifically, we evaluated the role of hyaluronic acid (HA), heparan sulfate (HS), and sialic acid (SA) in NO* and O2- mechanotransduction. Twenty-seven ex-vivo porcine superficial femoral arteries were incubated with either heparinase III, hyaluronidase, or neuraminidase, to remove HS, HA, or SA, respectively, from the glycocalyx. The arteries were then subjected to steady state flow and the effluent solution was measured for nitrites and the vessel diameter was tracked to quantify the degree of vasodilation. Our results show that removal of HA decreased both nitrites and vasodilation, and tempol treatment had no reversing effect. Degradation of HS proteoglycans decreased NO* bioavailability through an increase in O2- production as indicated by fluorescent signals of dihydroethidium (DHE) and its area fraction (209±24% increase) and also removed extracellular O2- dismutase (ecSOD) (67±9% decrease). The removal of SA also increased O2- production as indicated by DHE fluorescent signals (86±17% increase) and the addition of tempol, a mimic O2- scavenger, restored both NO* availability and vasodilation in both heparinase and neuraminidase treated vessels. This implies that HS and SA are not directly involved in WSS mediated NO* production. This study implicates HA in WSS-mediated NO* mechanotransduction and underscores the role of HS and SA in ROS regulation in vessel wall in response to WSS stimulation.

Keywords: Mechanotransduction, Wall shear stress, hyaluronic acid, heparan sulfate, sialic acid

Introduction

Endothelial function is mediated by the blood flow rate in an artery, or wall shear stress (WSS) (22,23,40). Although integrin-cytoskeleton interaction, regulated by Src, is considered pivotal in the pathway of mechanical transmission into biochemical signals (12,34,35,55), it is not clear how WSS activates the interaction. The mechanotransduction may be mediated by the tension in cell membrane exposed to WSS or the drag shear force between endothelial cells and matrix.

Recently, the glycocalyx has been suggested to mediate the mechanotransduction of WSS (46,58,65). Endothelial glycocalyx is the membrane macromolecules that are produced by endothelial cells. The constituents of glycocalyx include hyaluronic acid (HA) glycosaminoglycans, heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans, sialic acid (SA) glycosaminoglycans, thrombomodulin, and others. Since the glycocalyx connects to the cell membrane (either on membrane proteins, lipid layer, or transmembrane, Syndecan) and is exposed to the extracellular space, it can potentially mediate mechanical transduction (65).

The individual components (HA, HS, and SA) of glycocalyx have been implicated in NO* production when endothelial cells are exposed to WSS (17,26,45,50). The production of superoxide is also found to increase in blood vessel when WSS is elevated (8,36), which indicate that superoxide may be involved in endothelial mechanotransduction. The cumulative evidence indicates that NADPH oxidase may be a major donor of electrons to oxygen to form superoxide in response to WSS. NADPH oxidase is comprised of transmembrane NOX oxidase and p22phox and cytoplasmic subunits: p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, Rac, etc. NOX oxidase has a tail made up of extracellular glycoprotein. Integrin can activate NADPH oxidase through cytosolic signaling such as Rac to produce superoxide. It is unclear whether glycocalyx serves as a mechanosensor in the WSS mediated superoxide production. It is observed when the glycocalyx layer is degraded, flow-dependent vasodilation and NO* bioavailability is compromised (1,5,9). Therefore, it is both physiologically and pathophysiologically important to identify whether and how glycocalyx mediates O2- production in response to changes in WSS.

We hypothesize that the glycocalyx is involved in mechanotransduction in both endothelial NO* and O2- production. We focus on HS, SA, and HA as the three glycocalyx components that affect NO* and O2- production. The results validate the hypothesis regarding the mechano-sensory role of HA in NO* production and implicate the role of HS and SA in the regulation of O2- production. The physiological and pathophysiological implications are ramified.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation

Twenty-seven farm pigs weighing 30±5kg were used in this study. Surgical anesthesia was induced with ketamine (20 mg kg-1, i.m.) and atropine (0.05 mg kg-1) and maintained with isofluorane (1-2%). Ventilation with 100% O2 was provided with a respirator to maintain values of PO2 and PCO2 (approximately 500 and 35 mmHg, respectively). A 4-6 cm length of the right superficial femoral artery was dissected and transferred to ice-cold physiological saline solution (PSS, in mM: 5.5 Dextrose, 4.7 KCl, 119 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.17 KH2PO4, 1.17 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2H2O). Before the vessel was excised, two 6-0 sutures were sutured onto the adventitia to determine the change of blood vessel length from the in-vivo to ex-vivo state as well as to mark the proximal and distal segments. The animals were killed with an overdose of anesthesia. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with national and local ethical guidelines, including the Institute of Laboratory Animal Research (ILAR) Guide, Public Health Service (PHS) policy, Animal Welfare Act and an approved University of California Irvine IACUC protocol.

Isolated Vessel Preparation

The PSS was initially bubbled from bottom of the flask for 30 min with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to stabilize the pH at 7.4 and saturate the oxygen in the solution for all experiments. Since the bubbled PSS may generate superoxide in the solution, the PSS was perfused through the vessel 5 minutes after the bubbling was stopped, since the superoxide life span is about 2 seconds in water (67). We also verified that there was no difference in fluorescent signals of dihydroethidium in vessel tissue incubated with either PSS or HEPES-PSS which does not require aeration with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (24).

Following a previous protocol (41), the two ends of the superficial femoral artery were cannulated and stretched to the in-vivo length in a vessel bath containing PSS at 37±1°C. The proximal portion of each femoral artery was first connected to an inflow container and the distal segment connected to an outflow container, both of which were filled with PSS solution containing 1% porcine serum albumin (PSA; Sigma) at 37±1°C with pH of 7.4. The distal segment was connected to an outflow container by a short tube with a stopcock that was used to sample the effluent solution. This setup was used for all experiments.

The flow rate was monitored with an ultrasonic probe (TS410, Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca, NY) placed in series with the vessel. The perfusion pressure (inlet pressure) was maintained at 35 mmHg since 60 mmHg (physiologic pressure in superficial femoral artery) causes over-stretch of the vessel ex-vivo in the absence of surrounding tissue (41). We also noted that the myogenic response was unstable in the superficical femoral artery of pig while intraluminal pressure was elevated to physiologic pressure (∼60 mmHg). The application of intraluminal pressure of 35 mmHg caused a relatively stable myogenic response. While maintaining a constant pressure at 35 mmHg at the inlet of vessel segment, the resistance of the outlet tube was varied with a graded clamp to change the flow rate through the vessel. We did not observe a significant change in diameter with change of outlet tube resistance. Hence, the observed variation in diameter was the result of the vasoreactivity-induced changes of flow and WSS and not transmural pressure.

The degradation of components of glycocalyx with specific enzymes

Heparinase III (from Flavobacterium heparanum; Sigma) was used to remove the HS component of the glycocalyx in seven vessels (17). A 10 ml of 15 mU/ml of heparinase in PSS was injected into the vessel and incubated for 2 hrs at 37°C. After heparinase incubation, the vessel was washed out with PSS + 1% PSA for 10 min prior to measurements. The heparinase solution was prepared within 2 months of the experiment and divided into aliquots and stored in -20°C. The heparinase + PSS solution was prepared 15 min before application.

Following previous protocols for active hyaluronidase treatment (45, 62, 63), the lumen of vessel was incubated with PSS + 1% PSA + hyaluronidase (14 μg/ml; Type IV-S from bovine testes; Sigma) for 20 min and then washed out with PSS solution for 10 min to remove of HA. All solutions were kept at 37°C and pH of 7.4. Seven vessels were included in this group.

Following previous protocols for neuraminidase treatment (26, 52), the vessel was incubated with PSS + 1% PSA + neuraminidase (2 U/ml; Type V from Clostridium perfringens; Sigma) for 40 min and then washed out with PSS solution for 10 min to remove SA. All solutions were kept at 37°C and pH of 7.4. Seven vessels were included in this group.

Tempol Treatment

To assess the role of O2- in the vessel, tempol (4-hydroxy-tempol, a superoxide dismutase mimic superoxide scavenger) was added to the perfusate. The vessel segments were incubated with the tempol (1mM with PSS + 1% PSA) solution for 10 min at 37°C and were then perfused with the tempol solution for the measurements as outlined below. Tempol was not applied in control vessel segment since we found in preliminary studies that Tempol did not affect WSS-mediated NO* production in ex-vivo arterial segment (41).

Experimental Protocol

For control samples, the vessels were perfused with PSS + 1% PSA for 90 seconds, after which samples were collected in duplicates from the effluent solution. The vessels were then subjected to either heparinase III, hyaluronidase, or neuraminidase treatment (as described above) and the same perfusion and sample collection method was repeated. Next, the vessels were exposed to tempol treatment (as detailed above) and the same perfusion and sample collection method was again repeated.

To confirm endothelium viability, the system was connected to a pressure transducer and the vessel was constricted with 10-6 M phenylephrine (Sigma) solution, causing a marked increase in pressure within the vessel. Once the pressure stabilized, 10-7 M acetylcholine (Sigma) solution was introduced in the vessel bath, causing NO*-dependent endothelium derived relaxation and a drop in pressure. Endothelial viability was tested before and after each experiment. Only vessels with positive responses were included in the analysis.

Vasodilation

The vasodilation was evaluated by the ratio of outer diameter (D/D0) where D0 was the outer diameter of the vessel at zero flow and 35 mmHg. Since the vessel was allowed to fully develop vascular tone at in vivo stretch and pressure before perfusion, D0 was ∼15% smaller than in vivo outer diameter. The degradation enzymes did not change D0 significant. D is the outer diameter of the vessel at the same pressure (35 mmHg) and with perfusion of flow over a 1 minute period when the diameter reached a vasodilatory plateau. The outer diameter of the vessel was tracked by a charge-couple device (CCD) camera attached to a microscope and the measurements were made with a dedicated software (DiamTrak v3+, Australia).

Wall Shear Stress

The WSS of the artery was computed from the equation for laminar flow in circular cylinder as:

| (1) |

where Di is the internal diameter of the vessel, μ is the fluid viscosity and Q is the volumetric flow rate. The inner diameter in Eq. 1 was calculated through the incompressibility condition, which for a cylindrical vessel is given by:

| (2) |

where Di and Do are the inner and outer diameter at the loaded state (stretched to in-vivo length and pressurized), respectively, and Ao, is the wall area in the no-loaded state (no stretch and pressure), which was measured at the midpoint of the vessel segment from a transverse section of the blood vessel following the experiment. The stretch ratio, λ, is given by λ = l lo-1, where l and lo are the vessel lengths in the loaded and no-loaded states, respectively. Using the diameter of each vessel segment, we computed the perfusion flow rate, Eq. (1), to provide WSS of about 13 dynes/cm2. Since the diameter varied from vessel to vessel, the flow rate was varied accordingly to provide a similar WSS.

Measurement of Nitrite using Griess's method

The perfusate collected during the experiment was assayed for nitrite, the oxidation of NO by oxygen in aqueous solution. Approximately 200 μl of perfusate was collected and 10 μl of the solution was injected into a high performance liquid chromatography machine (ENO-20 NOx Analyzer; EiCom, Kyoto). The minimum detectable concentrations are < 5nM in pH-neutral solution. The signal ratio of physiological flow rate to zero flow was about 3:1. The method is described in detail by Zeballos et al. (68) and Lu and Kassab (41). Briefly, the peak of detected voltage from nitrite was converted into nitrite concentration by use of a calibration solution. The concentrations were corrected for contamination by subtraction of the control nitrite concentration collected proximal to the vessel segment. Nitrite production rate was then calculated as the product of perfusion rate and nitrite concentration.

ecSOD Analysis

Six vessels were used for esSOD and superoxide analysis. The excised vessel was divided into two parts for ecSOD and superoxide analysis, respectively. The vessel segment used for ecSOD fluorescent analysis was cut into four rings (∼1 cm for every ring) where one ring served for control, one was incubated with heparinase III at 37°C for 2 hrs, one was incubated with hyaluranoidase at 37°C for 20 min, and one was incubated with neuraminidase at 37°C for 30 min. The rings were then washed with PSS for 5 minutes, fixed with 10% formalin in phosphate buffer, and stored in -20°C. The ring was then embedded in tissue freezing medium, cryo-sectioned at 25 μm, and placed on a glass slide. Slides were then washed 3 times in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) for 5 min each, incubated with 10% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and washed three times in PBS for 5 min each. The slides were then treated with a primary rabbit anti-ecSOD polyclonal antibody (1:100 dilution in 1.5% BSA in PBS, Stressgen Bioreagents) for 1 hr at room temperature and then washed with PBS for 5 min × 3. The slides were then incubated with a secondary antibody, FITC (1:200 dilution in 1.5% BSA in PBS, Molecular Probes), for 1 hr at room temperature and washed again with PBS for 5 min × 3. The slides were cover-slipped and mounted for confocal imaging.

Superoxide Analysis

Six vessel rings were used for superoxide measurements. After taking a small ring as a control, the vessel was first exposed to either heparinase III, hyaluronidase or neuraminidase treatment for 2 hrs, 20 min, and 30 min, respectively. The vessel was then washed with PSS for 5 min and subjected to a physiological flow rate of 60 ml/min and a 1 cm ring was excised for O2- analysis and placed in room temperature PSS, immediately cryo-sectioned at 25 μm, and placed on a glass slide. The glass slides were immediately treated with 0.1 μM Dihydroethidium (DHE, Sigma) solution to stain for O2- for 30 minutes at 37°C and washed with room temperature saline 3 times for 5 min each. DHE is a cell permeable O2- scavenger, which in the presence of O2- is oxidized to fluorescent ethidium bromide. Ethidium bromide is then trapped by intercalation with DNA, and the number of fluorescent nuclei indicates the relative level of O2- production (6). The coverslips were then mounted for confocal imaging.

Confocal Microscopy and Fluorescent Analysis

Fluorescent images were taken using a multi-photon laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510, Carl Zeiss Inc.). For ecSOD imaging, excitation wavelength was set at 488 nm and emission at 520 nm. For O2- imaging, excitation wavelength was set at 514 nm and emission at 610 nm. Ten images were taken from each of the eight samples (ecSOD: control, heparinase, hyaluronidase, neuraminidase; O2-: control, heparinase, hyaluronidase, neuraminidase) yielding a total of 80 images for image analysis. All images were compared by matching the autofluorescent intensity from the elastic lamina. Results were represented by percent fluorescence which was calculated as:

| (3) |

where Fluorescent Area represents stained areas and Total Area represents the entire area covered by the vessel. All image analysis was done using SigmaScan Pro 5 (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA).

Statistical Analysis

The data is presented as mean±SD. Statistical significance was determined by use of the Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The flow rate of perfusate, outer diameter, and WSS are listed in Table 1. The flow rate was computed by Eq. (1) using diameter of vessel to obtain a WSS of about 13 dynes/cm2. Because of vasodilation, the WSS varied in vessel segments somewhat but was still in the physiological range.

Table 1.

The flow rate, outer diameter, and WSS during ex-vivo perfusion.

| Treatment | Q (ml/min) | D (mm) | WSS (dyns/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 110.3±19.6 | 3.05±0.35 | 9.68±0.55 |

| Heparinase | 97.8±13.7 | 2.88±0.32 | 12.12±0.50* |

| Heparinase+Tempol | 102.6±15.9 | 3.03±0.26 | 9.77±0.78 |

| Control | 76.2±26.2 | 2.68±0.33 | 9.36±0.30 |

| Hyaluronidase | 46.8±26.9 | 2.28±0.48 | 10.97±0.43 * |

| Hyaluronidase+Tempol | 45.3±29.4 | 2.25±0.21 | 11.03±0.32 |

| Control | 75.0±10.0 | 2.66±0.05 | 9.42±0.28 |

| Neuraminidase | 60.8±14.3 | 2.48±0.14 | 11.03±0.44* |

| Neuraminidase+Tempol | 71.0±14.8 | 2.63±0.05 | 9.52±0.39 |

Q: flow rate of perfusate. D: outer diameter after 1 minute of flow onset. WSS: wall shear stress on arterial segment. HS (-): removal of Heparin Sulfate. HA (-): removal of Hyaluronic Acid. SA (-): removal of Sialic Acid.

p<0.05 in comparison with control

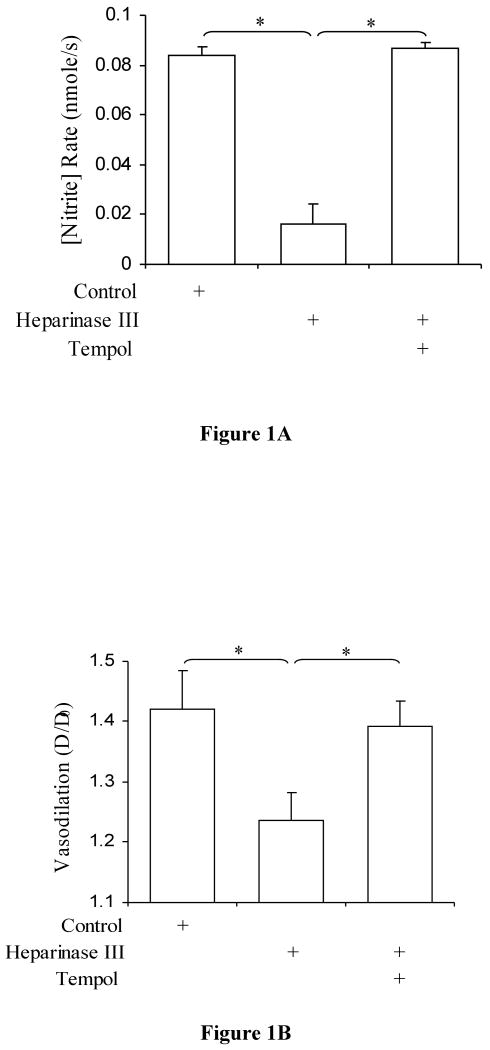

Tempol Restores Both NOx Production Rate and Vasodilation after removal of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans with Heparinase III

Nitrite production rates after removal of HS are presented in Figure 1. Previous studies have shown that heparinase III abolishes nitrite production in bovine aortic endothelial cell culture (17). Here, significant reduction of nitrite production rate was observed after heparinase III treatment (P < 0.0001 vs. control). The presence of tempol scavenged the O2- and restored nitrite production rates to control levels (P = 0.14) and increased nitrite production as compared to heparinase III treatment (P < 0.0001). We also measured vasodilation of the superficial femoral artery and found the degree of vasodilation to be compromised after the treatment of heparinase III and restored after treatment with Tempol (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A) Nitrite production rate in porcine superficial femoral artery after heparinase III treatment. Control (open bar), after treatment with 15 mU/ml heparinase III (hatched bar; P < 0.0001 vs. control; n=7), and after treatment with tempol (dotted bar; P < 0.0001 vs. heparinase III, P = 0.14, not significant vs. control; n=7) values are represented. The data represent mean ± SD. (*: P<0.05). B) Degree of Vasodilation in porcine superficial femoral artery after heparinase III treatment. Control (open bar), after treatment with 15 mU/ml heparinase III (hatched bar; P < 0.001 vs. control; n=7), and after treatment with tempol (dotted bar; P < 0.004 vs. heparinase III, P = 0.34, not significant vs. control; n=7) values are represented. The data represent mean ± SD. (*: P<0.05).

Under the present conditions, nitrite production reflects the NO* production released by endothelial cells into the perfusate since nitrite is the oxidation of NO* and oxygen in the solution (28). The removal of HS by heparinase III may remove ecSOD (see below) and elevate reactive oxygen species (ROS) on abluminal side of endothelium. This can reduce the release of NO* to perfusate and decrease the concentration of nitrite sampled in the outlet.

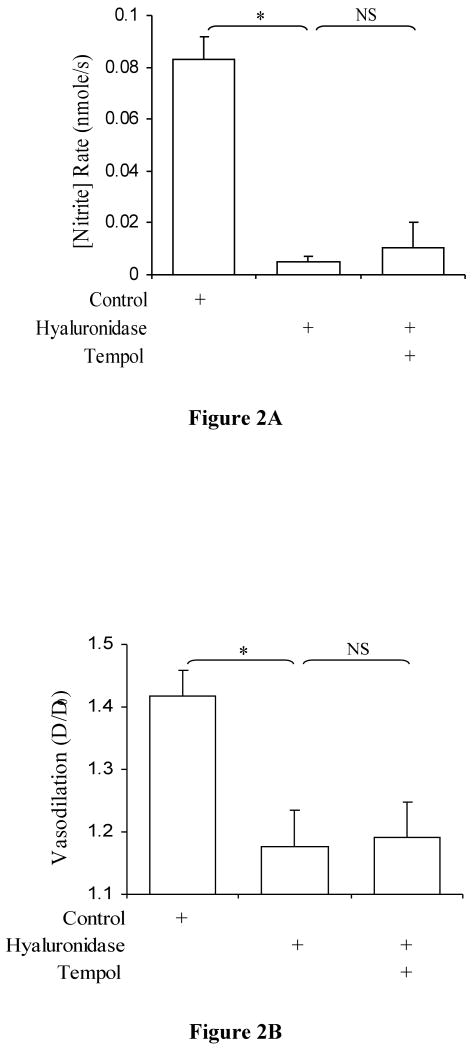

Treatment with Hyaluronidase impairs both the biological responsiveness of NO and Vasodilation even after Tempol treatment

Nitrite production rates after removal of HA are presented in Figure 2. Mochizuki et al. (45) have shown that NO production is impaired after hyaluronidase treatment. We have observed similar results as well as an impairment of vasodilation (Figures 2A and 2B). Our data also show that O2- is not implicated as tempol had no effect. Significant reduction of nitrite production rate was observed after hyaluronidase treatment and after tempol treatment as compared to control values (P < 0.0001 and P<0.0001, respectively). There was no significant difference between after hyaluronidase treatment and after tempol treatment (P=0.24). Coincident with the nitrite production rates, vasodilation was significantly reduced after hyaluronidase treatment and after tempol treatment (P<0.001 and P<0.01, respectively), and there was no significant difference between hyaluronidase and tempol treatment (P=0.11). WSS was significantly higher after hyaluronidase and after tempol treatment as compared to control (P<0.001 and P<0.002, respectively).

Figure 2.

A) Nitrite production rate in porcine superficial femoral artery after hyaluronidase treatment. Control (open bar), after treatment with 14 μg/ml hyaluronidase (hatched bar; P < 0.0001 vs. control; n=7), and after treatment with tempol (dotted bar; P < 0.0001 vs. hyalrunoidase, P = 0.14, not significant vs. control; n=7) values are represented. The data represent mean ± SD. (*: P<0.05 and NS: P>0.05). B) Degree of Vasodilation in porcine superficial femoral artery after hyaluronidase treatment. Control (open bar), after treatment with 14 μg/ml hyaluronidase (hatched bar; P < 0.001 vs. control; n=7), and after treatment with tempol (dotted bar; P < 0.004 vs. hyaluronidase, P = 0.34, not significant vs. control; n=7) values are represented. The data represent mean ± SD. (*: P<0.05 and NS: P>0.05).

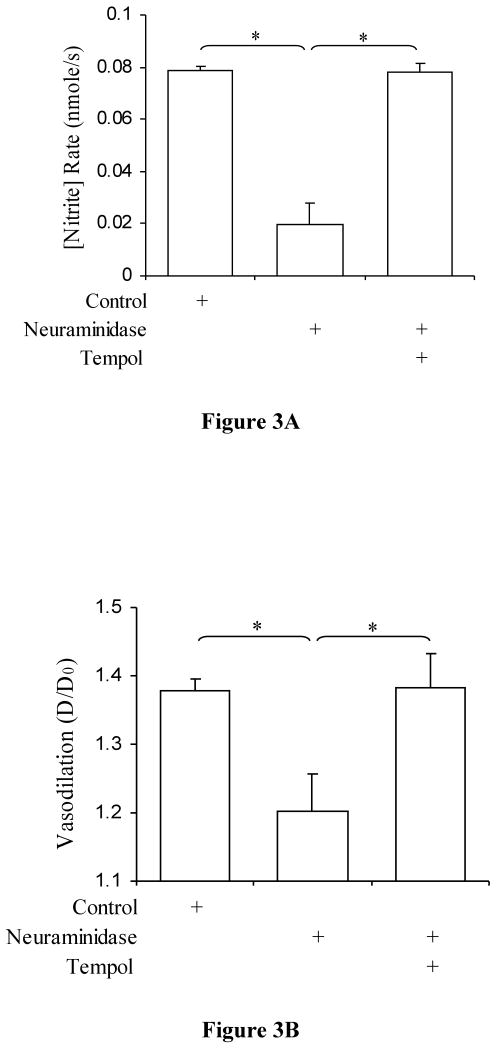

Tempol restores both NOx production rate and vasodilation after removal of Sialic Acids with Neuraminidase

Pohl et al. (26) and Hecker et al. (52) have shown that both NO* production and vasodilation is impaired after neuraminidase treatment. We observed similar results here (Figures 3A and 3B). Our data show that addition of tempol, however, restores both nitrite production and vascular tone. Significant reduction of nitrite production rate was observed after neuraminidase treatment as compared to control (P<0.0001) and significant restoration of nitrite values after tempol treatment as compared to neuraminidase treatment (P<0.0001). There was no significant difference between control and tempol treatment (P=0.42). Vasodilation coincided with the nitrite production rates (P<0.002 and P<0.003, respectively). There was no significant difference between control and after tempol treatment (P=0.43).

Figure 3.

A) Nitrite production rate in porcine superficial femoral artery after neuraminidase treatment. Control (open bar), after treatment with 2 U/ml neuraminidase (hatched bar; P < 0.0001 vs. control; n=7), and after treatment with tempol (dotted bar; P < 0.0001 vs. neuraminidase, P = 0.14, not significant vs. control; n=7) values are represented. The data represent mean ± SD. (*P<0.05). B) Degree of Vasodilation in porcine superficial femoral artery after neuraminidase treatment. Control (open bar), after treatment with 2 U/ml neuraminidase (hatched bar; P < 0.001 vs. control; n=7), and after treatment with tempol (dotted bar; P < 0.004 vs. neuraminidase, P = 0.34, not significant vs. control; n=7) values are represented. The data represent mean ± SD. (*: P<0.05).

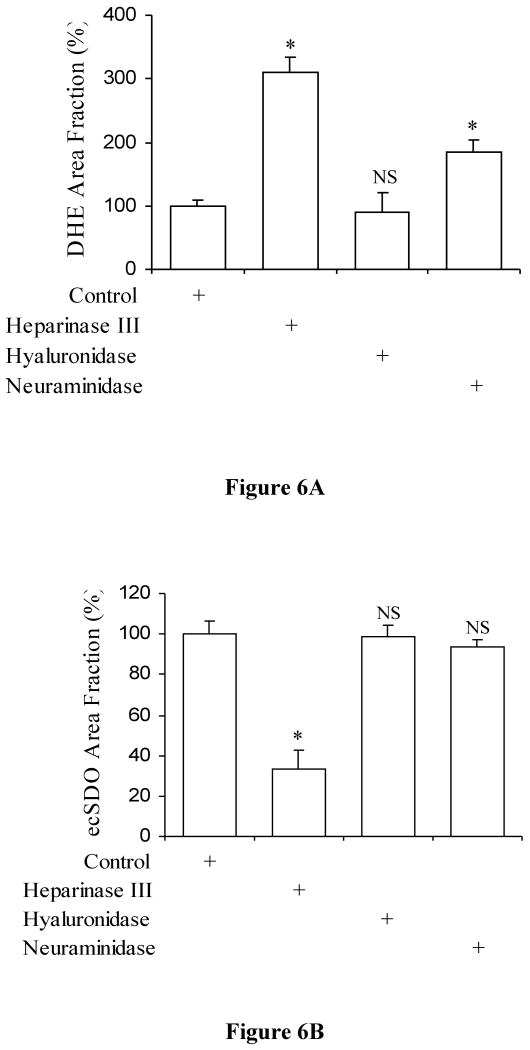

Heparinase and neuraminidase significantly increases superoxides in the vessel but hyaluronidase does not

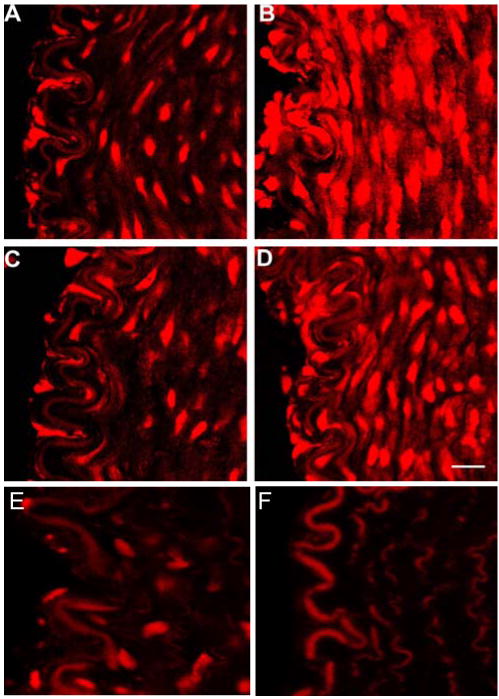

The O2- levels measured by DHE fluorescent signals and its area fraction after heparinase, after hyaluronidase, and after neuraminidase treatment were 309±24%, 91±30%, and 186±17%, respectively as compared to control (Figures 4 and 6). A significant increase was observed after heparinase (P<0.0001) and neuraminidase treatment (P<0.0001) as compared to control. No significant difference was observed after hyaluronidase treatment in comparison to control (P=0.18).

Figure 4.

DHE superoxide staining in porcine superficial femoral artery. A) Control staining. B) After heparinase treatment. C) After hyaluronidase treatment. D) After neuraminidase treatment. Vessels were subjected to a flowrate of 60 ml/min. E) Tempol treatment. F) Autofluorescence of elastic lamina and fibers without DHE incubation. Left is luminal side and right is the arterial wall. The autofluorescent elastic lamina provided a reference intensity for which all images were matched with. Bar=20μm.

Figure 6.

A) The area fraction of DHE fluorescent staining which indicates superoxides production in porcine superficial femoral artery after heparinase III, hyaluronidase, and neuraminidase treatment. Control (open bar) is shown as 100%. The data represent mean ± SD (*: P<0.05 and NS: P>0.05 from control). B) The area fraction of immunofluorescence of ecSOD in porcine superficial femoral artery after heparinase III, hyaluronidase, and neuraminidase treatment. Control (open bar) is shown as 100%. The data represents mean ± SD (*: P<0.05 and NS: P>0.05 from control).

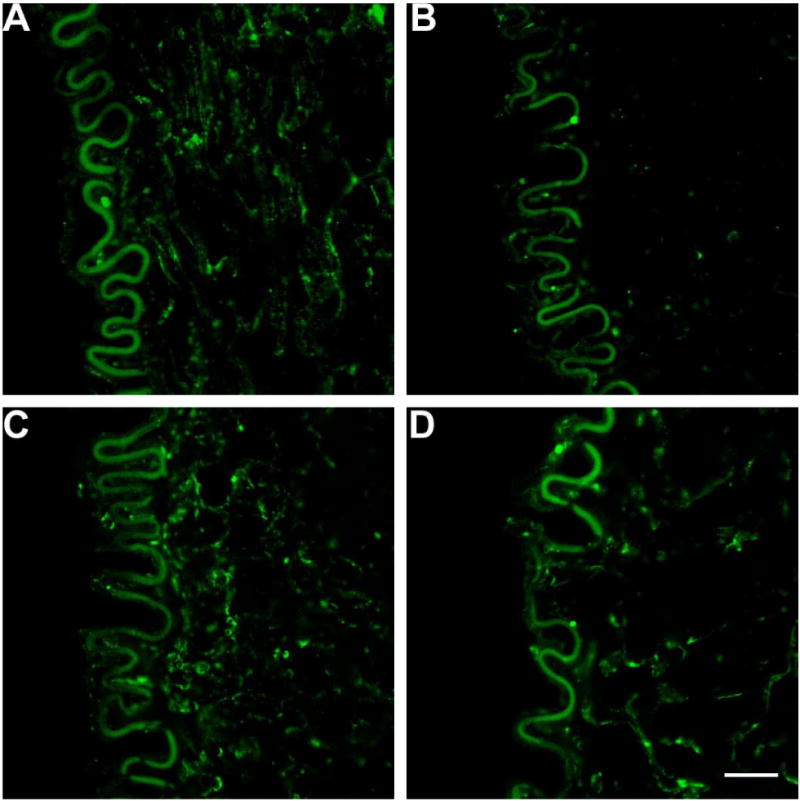

Heparinase significantly removes ecSOD but hyaluronidase and neurminidase do not

The presence of ecSOD after heparinase, after hyaluronidase, after neuraminidase treatment were 33±9%, 98±6%, and 93±4%, respectively as compared to control (Figures 5 and 7). A significant decrease was observed after heparinase treatment vs. control (P<0.02). No significant difference was observed after hyaluronidase (P=0.47) and neuraminidase treatment (P=0.18) vs. control. Therefore, removal of HS with heparinase III causes a 67±9% decrease in ecSOD distribution.

Figure 5.

ecSOD distribution with anti-ecSOD antibody and FITC staining in porcine superficial femoral artery. A) Control staining. B) heparinase treatment. C) hyaluronidase treatment. D) neuraminidase treatment. Vessels were incubated with respective agents then analyzed with immunofluorescent analysis. Left is luminal side and right is the arterial wall. The autofluorescent elastic lamina provided a reference intensity for which all images were matched with. Bar=20μm.

Discussion

This study showed that the three components (HS, HA, SA) of glycocalyx are implicated in flow-induced production of endothelial NO* in ex-vivo porcine artery. The absence of either HS, HA, or SA drastically suppressed WSS-induced production of NO* through different mechanisms. HA played an essential role in WSS-induced endothelial NO* production and was not involved in flow-induced ROS production. The HS and SA were implicated in vascular ROS production. The absence of HS (though removal of ecSOD) or SA increased vessel wall ROS in response to WSS stimulation. The vascular ROS (e.g., superoxide) signaling pathway implicates the important pathophysiologic effects in cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes.

In a number of pathological conditions, such as hypertension and the hyperglycemic state associated with diabetes, glycocalyx degradation has been documented. In spontaneously hypertensive rats, Ueno et al. (60) has shown that vascular permeability occurs through a marked decrease in the endothelial glycocalyx. Adachi et al. (1) have shown that in diabetic patients, glycation of ecSOD was observed and Nieuwdorp et al. (48) has shown loss of endothelial glycocalyx during acute hyperglycemia resulting in endothelial dysfunction and coagulation activation. Ikegami-Kawai et al. (30) showed that in diabetic Wistar and GK rats, production of hyaluronidases in kidney increased, the result of which can cleave off the HA component of the glycocalyx. There has been increasing evidence implicating HA as vital to the glycocalyx where removal of which can result in significant decrease in endothelial glycocalyx thickness, increased vascular permeability, adhesion of mononuclear cells and platelets to the endothelial surface, and attenuated NO* bioavailability (10,13,16,19,30,44,46-49,64). Since oxidative stress increases in cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and diabetes (2,10,11), it is important to understand the relation between the increase in oxidative stress and degradation of glycocalyx. The present observations provide evidence that glycocalyx is involved in ROS production in the vessel wall.

It has been well documented that ecSOD has a high affinity to the HS portion of the glycocalyx (14,15,20,21,42, 50,53). ecSOD has a positively charged heparin-binding domain that allows localization of ecSOD to HS proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix. With ecSOD being highly expressed in blood vessels (up to 70% of total SOD in blood vessel wall when assayed enzymatically) it is the predominant form in which O2- can be removed from the blood vessel wall (12,32,39,50,57). The majority of the ecSOD enzyme is present between the endothelial cells and the smooth muscle cells (Figure 5), and is vital in preserving NO* as it diffuses to the smooth muscle cells (21,50,57). A number of studies have shown that the ecSOD is vital in regulation of blood pressure, vascular function, modulation of vascular O2-, and preservation of NO*. Jonsson et al. (31) and Tarbell (58) suggested that the absence of ecSOD may lead to increased O2- states and reduction of NO* in cell culture. Furthermore, the enhanced oxidative stress in kidneys of spontaneously hypertensive rats might be attributed to NADPH oxidase overexpression and the loss of ecSOD (2). Our findings confirm the antioxidant role of HS proteoglycans and provide further evidence that HS proteoglycans are involved in flow-mediated vascular response.

SA in the glycocalyx have also been hypothesized to play a role in the mechanotransduction pathway suggested by the finding that vasorelaxation and NO* production was inhibited in the presence of SA removing-neuraminidase. Recently, Iijima et al. (29) has shown that SA, however, is vital in removing hydrogen peroxide and implicated the α-ketocarboxylic acid structure of SA in removal of other ROS. Several studies have previously shown the strong antioxidant properties of other α-keto acids such as pyruvate and alpha-lipoic acid (51). Here, we validated the antioxidant role of SA in flow-mediated vascular response.

It is possible that SA may have an intrinsic antioxidant property which removes O2- from the vasculature. Henricks et al. (27) showed that removal of SA enhances O2- generation in neutrophils and implies that neuraminidase unmasks receptor sites which stimulates metabolic bursts of O2-. Therefore, the inhibited vascular function and NO* bioavailability (26, 52) may be caused by an increase in O2- generation or accumulation. The implication that unmasking receptor sites after removal of SA may also occur after the removal of HS, which can cause an intracellular disruption, increasing superoxide production in response to shear stress.

WSS causes deformation of the HA in the glycocalyx which may interact with intracellular and cytoskeletal elements and activate cytosolic endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) signaling pathway (3, 4) since HA is anchored to plasma membrane by interaction with CD44 that localizes in caveolae with signaling molecules including eNOS (7,18,33,37,54,61). A recent study by Gouverneur et al. shows that fluid shear stress is a vital stimulus for glycocalyx synthesis. Specifically, they showed the recruitment of hyaluronan to the endothelial glycocalyx in response to WSS (25). This recruitment may explain the important role of HA in NO* production in response to increased shear stress on the vessel wall; i.e., increase in HA by WSS activates eNOS and results in the increase in NO* production. Our data shows NO* production and vasodilation are impaired in the absence of HA and this was not due to O2- imbalance and supports the notion that HA mediates WSS-induced NO* production by direct eNOS activation.

Critique of the Methods

Superoxide, one of the ROS, is formed by transport of an electron to molecular oxygen. In vascular tissue, NADPH oxidase, Xanthine Oxidase, mitochondrial electron leakage, and uncoupling eNOS may donate electrons to molecular oxygen. The oxygen concentration in the perfusate may contribute to ROS in vascular tissue. Since the oxygen concentration decreases with depth of water exposed to air, the PSS was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to eliminate hypoxia. The oxygen concentration in bubbled PSS was made similar to the oxygen concentration on the surface (<1 cm depth) of PSS without aeration. This preparation was used to ensure viable endothelial cells as confirmed by vessel reactivity.

Although the enzymatic degradation has been validated in cell culture, it could not be confirmed in ex-vivo tissue. Immunostains and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays work well in cultured monolayer endothelial cells (58). The vascular wall, however, contains not only endothelial cells but also vascular smooth muscle cells and adventitia. As the vascular wall is exposed to specific enzyme, the apical glycocalyx on endothelial cells may be degraded more significantly than the dorsal. It is reasonable to assume the apical glycocalyx on ECs was degraded in the vascular tissue of this study similar to cultured monolayer cells. In these experiments, the effectiveness and duration of incubation of the enzymes were first verified with cultured endothelial cells and then translated to the ex-vivo vessels.

Glycocalyx degradation may affect the interaction between the dorsal glycocalyx on ECs and basement membrane, which may alter the signal pathway of endothelial integrin in response to WSS. Integrin plays the role of translating extracellular mechanical stimulation into cellular signaling. A disruption of the connection between integrin and extracellular matrix can change cellular events. The signaling pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells may be affected after glycocalyx degradation since the enzyme may degrade the glycocalyx in the matrix of smooth muscle cells. Fortunately, WSS exerts its effect largely on endothelial cells but much less so on the vascular smooth muscle cells.

Summary and Future Studies

The present study shows that glycocalyx is involved in endothelial WSS-mediated mechanotransductions through various mechanisms. HS proteoglycans and SA act as important mediators for vascular oxidative stress. The role of HS as a mechanosenor for NO* is controversial. Here, we found that removal of HS which can impact the nearby SOD affects the superoxide balance which in turn affects the NO* bioavilability. Hence, this study suggests that HS is not directly involved in WSS-mediated NO* production. Rather, we found that HA is the essential mechansenor for WSS-mediated NO* production.

Future studies should examine the dynamic properties of the glycocalyx and the mechanism of mechanical stimulus activating NO* and superoxide through glycocalyx. Furthermore, molecular targeting of specific component of glycocalyx with magnetic beads should allow specific molecular deformation which may lead to a better understanding of the involvement of glycocalyx. These studies have tremendous physiological and pathophysiological significance as bioengineering of the glycocalyx may help restore vessel wall function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Quang Dang, Carlos Linares, and Eric Budiman for the animal preparation. Dr. Xiaomei Guo provided guidance for the immunohistochemical preparations.

Grants: This research was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-084529 and HL-055554-11.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adachi T, Ohta H, Hirano K, Hayashi K, Marklund SL. Non-enzymic glycation of human extracellular superoxide dismutase. Biochem J. 1991;279(Pt 1):263–267. doi: 10.1042/bj2790263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler S, Huang H. Oxidant stress in kidneys of spontaneously hypertensive rats involves both oxidase overexpression and loss of extracellular superoxide dismutase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287(5):F907–913. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00060.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali MH, Schumacker PT. Endothelial responses to mechanical stress: where is the mechanosensor? Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5 Suppl):S198–206. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews KL, Triggle CR, Ellis A. NO and the vasculature: where does it come from and what does it do? Heart Fail Rev. 2002;7(4):423–445. doi: 10.1023/a:1020702215520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagi Z, Toth E, Koller A, Kaley G. Microvascular dysfunction after transient high glucose is caused by superoxide-dependent reduction in the bioavailability of NO and BH(4) Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(2):H626–633. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00074.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagi Z, Frangos JA, Yeh JC, White CR, Kaley G, Koller A. PECAM-1 mediates NO-dependent dilation of arterioles to high temporal gradients of shear stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(8):1590–1595. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000170136.71970.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourguignon LY, Singleton PA, Zhu H, Diedrich F. Hyaluronan-mediated CD44 interaction with RhoGEF and Rho kinase promotes Grb2-associated binder-1 phosphorylation and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling leading to cytokine (macrophage-colony stimulating factor) production and breast tumor progression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(32):29420–29434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castier Y, Brandes RP, Leseche G, Tedgui A, Lehoux S. p47phox-dependent NADPH oxidase regulates flow-induced vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2005;97:533–540. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000181759.63239.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattaruzza M, Guzik TJ, Slodowski W, Pelvan A, Becker J, Halle M, Buchwald AB, Channon KM, Hecker M. Shear stress insensitivity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression as a genetic risk factor for coronary heart disease. Circ Res. 2004;95(8):841–847. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145359.47708.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Channon KM, Qian H, George SE. Nitric oxide synthase in atherosclerosis and vascular injury: insights from experimental gene therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(8):1873–81. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.8.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Didion SP, Ryan MJ, Didion LA, Fegan PE, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Increased superoxide and vascular dysfunction in CuZnSOD-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2002;91(10):938–944. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043280.65241.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399(6736):601–5. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dusserre N, L'Heureux N, Bell KS, Stevens HY, Yeh J, Otte LA, Loufrani L, Frangos JA. PECAM-1 interacts with nitric oxide synthase in human endothelial cells: implication for flow-induced nitric oxide synthase activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(10):1796–1802. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000141133.32496.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faraci FM, Didion SP. Vascular protection: superoxide dismutase isoforms in the vessel wall. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(8):1367–1373. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133604.20182.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fattman CL, Schaefer LM, Oury TD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase in biology and medicine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(3):236–256. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Dixit M, Busse R. Role of PECAM-1 in the shear-stress-induced activation of Akt and the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 18):4103–4111. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Florian JA, Kosky JR, Ainslie K, Pang Z, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a mechanosensor on endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2003;93(10):e136–142. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000101744.47866.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita Y, Kitagawa M, Nakamura S, Azuma K, Ishii G, Higashi M, Kishi H, Hiwasa T, Koda K, Nakajima N, Harigaya K. CD44 signaling through focal adhesion kinase and its anti-apoptotic effect. FEBS Lett. 2002;528(13):101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujiwara K. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 and mechanotransduction in vascular endothelial cells. J Intern Med. 2006;259(4):373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukai T, Galis ZS, Meng XP, Parthasarathy S, Harrison DG. Vascular expression of extracellular superoxide dismutase in atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(10):2101–2111. doi: 10.1172/JCI2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukai T, Folz RJ, Landmesser U, Harrison DG. Extracellular superoxide dismutase and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55(2):239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399(6736):597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallis B, Corthals GL, Goodlett DR, Ueba H, Kim F, Presnell SR, Figeys D, Harrison DG, Berk BC, Aebersold R, Corson MA. Identification of flow-dependent endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation sites by mass spectrometry and regulation of phosphorylation and nitric oxide production by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(42):30101–30108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godbole AS, Lu X, Guo X, Kassab GS. NADPH oxidase has a directional response to shear stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296(1):H152–158. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01251.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gouverneur M, Spaan JA, Pannekoek H, Fontijn RD, Vink H. Fluid shear stress stimulates incorporation of hyaluronan into endothelial cell glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;290(1):H458–462. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00592.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hecker M, Mulsch A, Bassenge E, Busse R. Vasoconstriction and increased flow: two principal mechanisms of shear stress-dependent endothelial autacoid release. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(3 Pt 2):H828–833. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.3.H828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henricks PA, van Erne-van der Tol ME, Verhoef J. Partial removal of sialic acid enhances phagocytosis and the generation of superoxide and chemiluminescence by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Immunol. 1982;129(2):745–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ignarro LJ, Fukuto JM, Griscavage JM, Rogers NE, Byrns RE. Oxidation of nitric oxide in aqueous solution to nitrite but not nitrate: comparison with enzymatically formed nitric oxide from L-arginine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(17):8103–8107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iijima R, Takahashi H, Namme R, Ikegami S, Yamazaki M. Novel biological function of sialic acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid) as a hydrogen peroxide scavenger. FEBS Lett. 2004;561(13):163–1666. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikegami-Kawai M, Okuda R, Nemoto T, Inada N, Takahashi T. Enhanced activity of serum and urinary hyaluronidases in streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar and GK rats. Glycobiology. 2004;14(1):65–72. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonsson LM, Rees DD, Edlund T, Marklund SL. Nitric oxide and blood pressure in mice lacking extracellular-superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Res. 2002;36(7):755–758. doi: 10.1080/10715760290032629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung O, Marklund SL, Geiger H, Pedrazzini T, Busse R, Brandes RP. Extracellular superoxide dismutase is a major determinant of nitric oxide bioavailability: in vivo and ex vivo evidence from ecSOD-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2003;93(7):622–629. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000092140.81594.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knudson W, Aguiar DJ, Hua Q, Knudson CB. CD44-anchored hyaluronan-rich pericellular matrices: an ultrastructural and biochemical analysis. Exp Cell Res. 1996;228(2):216–228. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuchan MJ, Frangos JA. Role of calcium and calmodulin in flow-induced nitric oxide production in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(3 Pt 1):C628–636. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.3.C628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuchan MJ, Jo H, Frangos JA. Role of G proteins in shear stress-mediated nitric oxide production by endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;267(3 Pt 1):C753–758. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.3.C753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurindo FR, Pedro Mde A, Barbeiro HV, Pileggi F, Carvalho MH, Augusto O, da Luz PL. Vascular free radical release. Ex vivo and in vivo evidence for a flow-dependent endothelial mechanism. Circ Res. 1994;74:700–709. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lesley J, Hascall VC, Tammi M, Hyman R. Hyaluronan binding by cell surface CD44. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(35):26967–26975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Förstermann U. Nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. J Pathol. 2000;190(3):244–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<244::AID-PATH575>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(5):R1014–1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Zheng J, Bird IM, Magness RR. Effects of pulsatile shear stress on signaling mechanisms controlling nitric oxide production, endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation, and expression in ovine fetoplacental artery endothelial cells. Endothelium. 2005;12(12):21–39. doi: 10.1080/10623320590933743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu X, Kassab GS. Nitric oxide is significantly reduced in ex vivo porcine arteries during reverse flow because of increased superoxide production. J Physiol. 2004;561(Pt 2):575–582. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marklund SL. Human copper-containing superoxide dismutase of high molecular weight. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(24):7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moncada S. Nitric oxide in the vasculature: Physiology and pathophysiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;811:60–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mochizuki S, Goto M, Chiba Y, Ogasawara Y, Kajiya F. Flow dependence and time constant of the change in nitric oxide concentration measured in the vascular media. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1997;37(4):497–503. doi: 10.1007/BF02513336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mochizuki S, Vink H, Hiramatsu O, Kajita T, Shigeto F, Spaan JA, Kajiya F. Role of hyaluronic acid glycosaminoglycans in shear-induced endothelium-derived nitric oxide release. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(2):H722–726. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00691.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nieuwdorp M, Meuwese MC, Vink H, Hoekstra JB, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. The endothelial glycocalyx: a potential barrier between health and vascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16(5):507–511. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000181325.08926.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nieuwdorp M, van Haeften TW, Gouverneur MC, Mooij HL, van Lieshout MH, Levi M, Meijers JC, Holleman F, Hoekstra JB, Vink H, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. Loss of endothelial glycocalyx during acute hyperglycemia coincides with endothelial dysfunction and coagulation activation in vivo. Diabetes. 2006;55(2):480–486. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nieuwdorp M, Mooij HL, Kroon J, Atasever B, Spaan JA, Ince C, Holleman F, Diamant M, Heine RJ, Hoekstra JB, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES, Vink H. Endothelial glycocalyx damage coincides with microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):1127–3112. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osawa M, Masuda M, Kusano K, Fujiwara K. Evidence for a role of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cell mechanosignal transduction: is it a mechanoresponsive molecule? J Cell Biol. 2002;158:773–785. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oury TD, Day BJ, Crapo JD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase: a regulator of nitric oxide bioavailability. Lab Invest. 1996;75(5):617–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Packer L, Witt EH, Tritschler HJ. alpha-Lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19(2):227–250. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00017-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pohl U, Herlan K, Huang A, Bassenge E. EDRF-mediated shear-induced dilation opposes myogenic vasoconstriction in small rabbit arteries. Am J Physiol. 1991;261(6 Pt 2):H2016–2023. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sentman ML, Brannstrom T, Westerlund S, Laukkanen MO, Yla-Herttuala S, Basu S, Marklund SL. Extracellular superoxide dismutase deficiency and atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(9):1477–1482. doi: 10.1161/hq0901.094248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherman L, Sleeman J, Herrlich P, Ponta H. Hyaluronate receptors: key players in growth, differentiation, migration and tumor progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6(5):726–733. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shyy JY, Chien S. Role of integrins in endothelial mechanosensing of shear stress. Circ Res. 2002;91(9):769–775. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038487.19924.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith AR, Hagen TM. Vascular endothelial dysfunction in aging: loss of Akt-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and partial restoration by (R)-alpha-lipoic acid. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31(Pt 6):1447–1449. doi: 10.1042/bst0311447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stralin P, Karlsson K, Johansson BO, Marklund SL. The interstitium of the human arterial wall contains very large amounts of extracellular superoxide dismutase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15(11):2032–2036. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.11.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tarbell JM, Pahakis MY. Mechanotransduction and the glycocalyx. J Intern Med. 2006;259(4):339–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thorne RF, Legg JW, Isacke CM. The role of the CD44 transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in co-ordinating adhesive and signalling events. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 3):373–380. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueno M, Sakamoto H, Liao YJ, Onodera M, Huang CL, Miyanaka H, Nakagawa T. Blood-brain barrier disruption in the hypothalamus of young adult spontaneously hypertensive rats. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122(2):131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0684-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vachon E, Martin R, Plumb J, Kwok V, Vandivier RW, Glogauer M, Kapus A, Wang X, Chow CW, Grinstein S, Downey GP. CD44 is a phagocytic receptor. Blood. 2006;107(10):4149–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van den Berg BM, Vink H, Spaan JAE. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circ Res. 2003;92:592–594. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000065917.53950.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Teeffelen JW, Dekker S, Fokkema DS, Siebes M, Vink H, Spaan JA. Hyaluronidase treatment of coronary glycocalyx increases reactive hyperemia but not adenosine hyperemia in dog hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(6):H2508–2513. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00446.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang A, Hascall VC. Hyaluronan structures synthesized by rat mesangial cells in response to hyperglycemia induce monocyte adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(11):10279–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weinbaum S, Zhang X, Han Y, Vink H, Cowin SC. Mechanotransduction and flow across the endothelial glycocalyx. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(13):7988–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332808100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wright KL, Ward SG. Interactions between phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and nitric oxide: explaining the paradox. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;4(3):137–143. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2001.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zang LY, Misra HP. EPR kinetic studies of superoxide radicals generated during the autoxidation of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-2,3-dihydropyridinium, a bioactivated intermediate of parkinsonian-inducing neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl- 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(33):23601–23608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeballos GA, Bernstein RD, Thompson CI, Forfia PR, Seyedi N, Shen W, Kaminiski PM, Wolin MS, Hintze TH. Pharmacodynamics of plasma nitrate/nitrite as an indication of nitric oxide formation in conscious dogs. Circulation. 1995;91(12):2982–2988. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.12.2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]