Abstract

Background

In the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT), 2201 stable patients with an occluded infarct-related artery (IRA) were randomized to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or optimal medical treatment alone (MED). There was no difference in the primary endpoint of death, re-MI or heart failure (CHF). We examined the prognostic impact of pre-randomization stress testing.

Methods

Stress testing was required by protocol except for patients with single vessel disease and akinesis/dyskinesis of the infarct zone. The presence of severe inducible ischemia was an exclusion criterion for OAT. We compared outcomes based on performance and results of stress testing.

Results

598 (27%) patients (297 PCI, 301 MED) underwent stress testing. Radionuclide imaging or stress echocardiography was performed in 40%. Patients who had stress testing were younger (57 vs. 59 years), had higher ejection fractions (49% vs. 47%), and had lower rates of death (7.8% vs. 13.2%), class IV CHF (2.4% vs. 5.5%), and the primary endpoint (13.9% vs. 18.9%) than patients without stress testing (all p<0.01). Mild-moderate ischemia was observed in 40% of patients with stress testing, and was not related to outcomes. Among patients with inducible ischemia, outcomes were similar for PCI and MED (all p>0.1).

Conclusions

In OAT, patients who underwent stress testing had better outcomes than patients who did not, likely related to differences in age and LV function. In patients managed with optimal medical therapy or PCI, mild-moderate inducible ischemia was not related to outcomes. The lack of benefit for PCI compared to MED alone was consistent regardless of whether stress testing was performed or inducible ischemia was present.

Introduction

Previous studies have indicated a prognostic benefit for revascularization in patients who have severe inducible ischemia early after acute myocardial infarction (MI)1, 2. However, the role of revascularization for patients with only mild-moderate ischemia has not been fully established, particularly among patients with persistent total occlusions of the infarct-related artery (IRA). In the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT), 2201 stable patients with a persistently occluded IRA after MI were randomized to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or optimal medical treatment alone (MED)3. Overall, there was no difference in the primary endpoint of death, recurrent MI or heart failure4. The objective of this analysis was to determine the impact of pre-randomization stress testing on clinical outcomes in OAT.

Methods

The design and results of OAT have been previously published3, 4. The trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute. Eligibility required angiographically documented total occlusion (TIMI flow 0–1) of the IRA at 3–28 days after MI and either ejection fraction < 50% or proximal occlusion of a major epicardial vessel. Patients were randomized to undergo PCI or optimal medical therapy alone (MED). Patients in the PCI group underwent revascularization within 24 hours after randomization. Stenting was recommended whenever technically feasible.

Stress testing with low level exercise or pharmacological stress was required by protocol except for patients with single vessel disease and akinesis/dyskinesis of the infarct zone. The type of stress (exercise or pharmacological) and use of imaging (radionuclide or echocardiography) were based on local clinical practice and left to the discretion of treating physicians and the findings were based on local laboratory interpretations. Patients with post-MI angina at rest or severe inducible ischemia in the IRA distribution were ineligible for OAT. Severe ischemia was defined as in previous guidelines and reperfusion trials1, 5–12. For exercise stress testing, severe ischemia was defined as exercise-induced ST segment depression ≥ 2mm, ST segment elevation ≥ 1 mm in leads without Q waves, inability to complete stage 1 of the standard Bruce Protocol without angina, failure to achieve 3 or 4 METS, or exertional hypotension presumed due to ischemia. For stress myocardial perfusion imaging, severe ischemia was defined as increased lung uptake with any reversible perfusion defect, reversible perfusion defects in multiple territories, or an extensive reversible perfusion defect occupying ≥ 20% of the left ventricle13.

The primary endpoint in OAT was the composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, or NYHA class IV heart failure. Secondary endpoints evaluated in this analysis included the individual components of the primary endpoint and the composite of death or myocardial infarction. The definition of reinfarction has been previously reported3, 4. Reinfarction was centrally adjudicated.

Baseline characteristics were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Comparisons by stress test performance (stress test performed vs. stress test not performed) and by stress test results (ischemia present vs. ischemia absent) were performed using chi square/Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student t-test for continuous variables. Estimates of the cumulative event rates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method14 and groups were compared by the log-rank test of the 5-year curves15. Hazard ratio and 99% confidence intervals were calculated by Cox proportional hazards regression models16. To control for the Type I error rate, it was pre-specified by the study protocol that a p-value of less than 0.01 would be considered as showing evidence of differences in secondary analysis. SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study analysis, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents.

Results

A total of 2201 patients were enrolled in OAT, including the 2166 patients enrolled as of December 31, 2005 that were included in the main OAT results publication4, and an additional 35 patients enrolled in the extension phase of the viability ancillary study in 2006. Stress testing was performed prior to randomization in 598 (27%) patients (297 in PCI group, 301 in MED group; p=0.84). The type of stress was exercise for 427 patients and pharmacological for 171 patients. The method for detecting ischemia was radionuclide imaging for 179 patients, echocardiography for 58 patients, and electrocardiography (ECG) for 357 patients. The details on the type of stress testing and the results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Type and Results of Pre-Randomization Stress Testing

| PCI Group (n=297) | MED Group (n=301) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Type of stress | 0.93 | ||

| Exercise | 215 (72%) | 212 (70%) | |

| Dobutamine | 27 (9%) | 28 (9%) | |

| Dipyridamole | 36 (12%) | 40 (13%) | |

| Adenosine | 13 (4 %) | 12 (4%) | |

| Other | 6 (2%) | 9 (3%) | |

| B. Method of recording | 0.77 | ||

| Radionuclide | 83 (28%) | 96 (32%) | |

| Echocardiography | 30 (10%) | 28 (9%) | |

| Electrocardiography | 182 (61%) | 175 (58%) | |

| Other | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| C. Stress test results for ischemia in IRA distribution: | 0.21 | ||

| Severe (Ineligible) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Moderate | 27 (9%) | 32 (11%) | |

| Mild | 100 (34%) | 80 (27%) | |

| None | 170 (57%) | 188 (63%) | |

| D. Stress test results for ischemia in non-IRA distribution: | 0.20 | ||

| Severe | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Moderate | 12 (4%) | 16 (5%) | |

| Mild | 39 (13%) | 40 (13%) | |

| None | 246 (83%) | 241 (80%) |

IRA = infarct-related artery; PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; MED = Medical Therapy Alone

The baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients who did or did not undergo pre-randomization stress testing are compared in Table 2. Patients who underwent stress testing were younger, less likely to have ST-elevation MI at presentation, loss of R-waves on the electrocardiogram, and left anterior descending coronary artery as the IRA, and had lower heart rates and higher ejection fractions. Among the patients who had stress testing performed, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the PCI and MED groups (data not shown).

Table 2.

Baseline Clinical & Angiographic Characteristics by Stress Test Performed

| Stress Test Performed (n=598) | No Stress Test Performed (n=1603) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57 ± 11 | 59 ± 11 | 0.002 |

| Caucasian | 498 (83%) | 1265 (79%) | 0.02 |

| Male | 483 (81%) | 1234 (77%) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes | 108 (18%) | 346 (22%) | 0.07 |

| Hypertension | 288 (48%) | 783 (49%) | 0.77 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 326 (55%) | 816/1602 (51%) | 0.14 |

| Family History of Coronary Disease | 227 (38%) | 656 (41%) | 0.21 |

| Current Smoker | 229 (38%) | 630 (39%) | 0.67 |

| Previous Angina | 136 (23%) | 359 (22%) | 0.86 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 69 (12%) | 178 (11%) | 0.77 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 22 (4%) | 60 (4%) | 0.94 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 29/596 (5%) | 54 (3%) | 0.10 |

| Renal Insufficiency | 12 (2%) | 18 (1%) | 0.11 |

| Prior Congestive Heart Failure | 8/596 (1%) | 44 (3%) | 0.05 |

| Prior Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 33 (6%) | 72 (5%) | 0.31 |

| Thrombolysis in 1st 24 hours | 123 (21%) | 301 (19%) | 0.35 |

| New York Heart Association Class 2–4 | 130/597 (22%) | 329 (21%) | 0.52 |

| New Q waves | 395 (66%) | 1080 (67%) | 0.56 |

| ST segment Elevation | 344/576 (60%) | 1066/1550 (69%) | <0.0001 |

| Loss of R waves | 214/576 (37%) | 699/1549 (45%) | 0.001 |

| Left Anterior Descending Infarct-Related Artery | 168 (28%) | 625 (39%) | <0.0001 |

| Collateral Vessels Present | 531/588 (90%) | 1391/1585 (88%) | 0.10 |

| Multivessel Coronary Disease | 109/591 (18%) | 270/1592 (17%) | 0.42 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 49 ± 11 | 47± 11 | 0.0004 |

| Number of Days from Myocardial Infarction to Randomization | 15 ± 8 | 10 ± 7 | <0.0001 |

| Glomerular Filtration Rate (mL/min/1.73m2) | 80 ± 20 | 81 ± 22 | 0.60 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 113 ± 38 | 122 ± 43 | 0.001 |

| Heart Rate | 70 ± 12 | 73 ± 12 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 120 ± 17 | 121 ± 19 | 0.26 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 72 ± 11 | 72 ± 12 | 0.95 |

| Killip Class II–IV | 113/595 (19%) | 304/1597 (19%) | 0.98 |

| Body Mass Index | 28 ± 5 | 29 ± 5 | 0.51 |

Values are presented as number (%) of patients or mean ± standard deviation.

Mild-moderate inducible ischemia was present in the IRA territory in 240 (40%) patients. Baseline characteristics for patients with and without inducible ischemia are shown in Table 3. Patients with inducible ischemia had shorter times from the index MI to randomization. Among the patients with inducible ischemia, there were no significant differences (p <0.01) between the PCI and MED groups. Compared to the patients without IRA ischemia, the patients with inducible ischemia in the IRA territory had similar rates of non-protocol PCI of the IRA (11.6% vs. 10.0%; p=0.9) and of other vessels (5.2% vs. 7.0%; p=0.62).

Table 3.

Baseline Clinical & Angiographic Characteristics by Inducible Ischemia

| Inducible Ischemia Present (n=240) | No Inducible Ischemia Present (n=358) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57 ± 11 | 58 ± 11 | 0.79 |

| Caucasian | 194 (81%) | 304 (85%) | 0.19 |

| Male | 204 (85%) | 279 (78%) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 48 (20%) | 60 (17%) | 0.31 |

| Hypertension | 125 (52%) | 163 (46%) | 0.12 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 144 (60%) | 182 (51%) | 0.03 |

| Family History of Coronary Disease | 97 (40%) | 130 (36%) | 0.31 |

| Current Smoker | 91 (38%) | 138 (39%) | 0.88 |

| Previous Angina | 64 (27%) | 72 (20%) | 0.06 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 33 (14%) | 36 (10%) | 0.17 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 9 (4%) | 13 (4%) | 0.94 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 14/239 (6%) | 15/357 (4%) | 0.36 |

| Renal Insufficiency | 4 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 0.63 |

| Prior Congestive Heart Failure | 5/239 (2%) | 3/357 (1%) | 0.19 |

| Prior Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 16 (7%) | 17 (5%) | 0.31 |

| Thrombolysis in 1st 24 hours | 48 (20%) | 75 (21%) | 0.78 |

| New York Heart Association Class 2–4 | 47 (20%) | 83 (23%) | 0.29 |

| New Q waves | 151 (63%) | 244 (68%) | 0.18 |

| ST segment Elevation | 133/232 (57%) | 211/344 (61%) | 0.34 |

| Loss of R waves | 79/232 (34%) | 135/344 (39%) | 0.21 |

| Left Anterior Descending Infarct-Related Artery | 62 (26%) | 106 (30%) | 0.31 |

| Collateral Vessels Present | 210/235 (89%) | 321/353 (91%) | 0.53 |

| Multivessel Coronary Disease | 44/238 (18%) | 65/353 (18%) | 0.98 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 50 ± 10 | 49± 11 | 0.07 |

| Number of Days from Myocardial Infarction to Randomization | 14 ± 8 | 16 ± 7 | 0.0001 |

| Glomerular Filtration Rate (mL/min/1.73m2) | 81 ± 19 | 80 ± 21 | 0.77 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 118 ± 40 | 111 ± 37 | 0.03 |

| Heart Rate | 69 ± 12 | 70 ± 12 | 0.60 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 119 ± 17 | 121 ± 17 | 0.32 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 72 ± 11 | 73 ± 10 | 0.33 |

| Killip Class II–IV | 40/239 (17%) | 73/356 (20%) | 0.25 |

| Body Mass Index | 29 ± 5 | 28 ± 5 | 0.02 |

Values are presented as number (%) of patients or mean ± standard deviation.

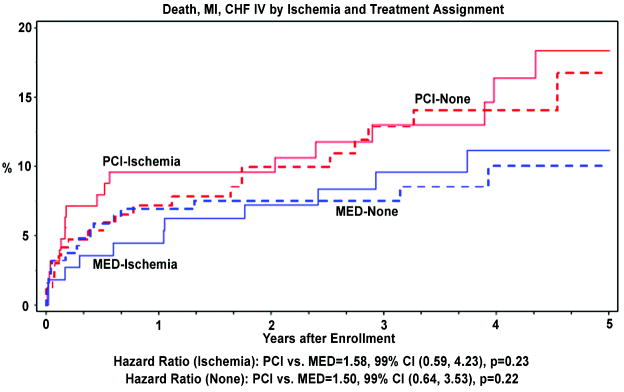

Clinical outcomes at 5 years are shown in Tables 4–5 and Figure 1. Compared to patients who had no stress testing performed, patients who underwent stress testing had lower rates of death, class IV congestive heart failure (CHF), and the composite primary endpoint (death, MI or class IV CHF). There were no significant differences between the PCI and MED treatment groups for primary or secondary endpoints in the subgroups of patients who did and did not undergo stress testing, and those who did and did not have inducible ischemia. There were no significant differences in outcomes between patients who did and did not have inducible ischemia. In a multivariate model, inducible ischemia was not independently related to the primary endpoint (p=0.50). There were no significant interactions for any of the endpoints between treatment group, performance of stress testing, and presence of inducible ischemia.

Table 4.

5-year Life Table estimates of Clinical Outcomes by Treatment Group & Stress Test Performed

| PCI Group Stress done (n=297) Not done (n=804) | MED Group Stress done (n=301) Not done (n=799) | P-Value (HR;99%CI) for stress test done vs stress test not done | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | HR | 99% CI | Unadjusted | Adjusted BL | ||||

| Death, MI or Class IV CHF | Stress Test | 39 (17.6%) | 27 (10.5%) | 0.08 | 1.55 | 0.81–2.95 | 0.007 (1.46;1.02–2.08) | 0.38 (1.14;0.78–1.66) |

| No Stress Test | 126 (19.4%) | 119 (18.4%) | 0.71 | 1.05 | 0.76–1.46 | |||

| Death | Stress Test | 17 (9.7%) | 13 (6.2%) | 0.37 | 1.39 | 0.54–3.59 | 0.0004 (2.02;1.21–3.38) | 0.01 (1.66;0.97–2.83) |

| No Stress Test | 75 (12.4%) | 79 (14.1%) | 0.66 | 0.93 | 0.61–1.41 | |||

| Nonfatal MI | Stress Test | 19 (8.0%) | 15 (5.9%) | 0.40 | 1.33 | 0.55–3.26 | 0.15 (0.74;0.43–1.27) | 0.03 (0.60;0.33–1.08) |

| No Stress Test | 39 (6.4%) | 26 (4.3%) | 0.11 | 1.50 | 0.78–2.88 | |||

| Death or MI | Stress Test | 35 (16.9%) | 25 (9.9%) | 0.13 | 1.49 | 0.76–2.93 | 0.05 (1.34;0.92–1.96) | 0.56 (1.09;0.73–1.63) |

| No Stress Test | 108 (17.7%) | 99 (17.2%) | 0.55 | 1.09 | 0.76–1.56 | |||

| Class IV CHF | Stress Test | 8 (3.1%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.37 | 1.67 | 0.38–7.24 | 0.007 (2.25;1.04–4.87) | 0.15 (1.56;0.70–3.49) |

| No Stress Test | 36 (5.6%) | 39 (5.3%) | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.50–1.66 | |||

PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; MED = Medical Therapy Alone; HR=Hazard Ratio; MI = Myocardial Infarction; CHF = Congestive Heart Failure

Table 5.

5-year Life Table Estimates of Clinical Outcomes by Treatment Group & Inducible Ischemia

| PCI Group Ischemia (n=127) No Ischemia (n=170) | MED Group Ischemia (n=113) No Ischemia (n=188) | P-Value (HR;99%CI)for ischemia vs no ischemia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | HR | 99% CI | Unadjusted | Adjusted BL | ||||

| Death, MI or Class IV CHF | Ischemia | 18 (18.4) | 11 (11.2) | 0.23 | 1.58 | 0.59–4.23 | 0.67 (1.11;0.59–2.11) | 0.77 (1.08;0.56–2.05) |

| No ischemia | 21 (16.7) | 16 (10.0) | 0.22 | 1.50 | 0.64–3.53 | |||

| Death | Ischemia | 8 (10.1%) | 3 (3.4%) | 0.18 | 2.49 | 0.43–14.2 | 0.48 (0.77;0.29–2.04) | 0.52 (0.78;0.29–2.10) |

| No ischemia | 9 (8.8%) | 10 (8.3%) | 0.93 | 1.04 | 0.32–3.40 | |||

| Nonfatal MI | Ischemia | 9 (9.2%) | 7 (6.9%) | 0.67 | 1.24 | 0.31–4.55 | 0.47 (1.28;0.53–3.11) | 0.72 (1.14;0.46–2.78) |

| No ischemia | 10 (6.8%) | 8 (5.2%) | 0.47 | 1.41 | 0.42–4.78 | |||

| Death or MI | Ischemia | 17 (19.1%) | 10 (10.2%) | 0.21 | 1.64 | 0.59–4.59 | 0.61 (1.14;0.59–2.24) | 0.73 (1.10;0.56–2.16) |

| No ischemia | 18 (14.6%) | 15 (9.8%) | 0.38 | 1.36 | 0.55–3.35 | |||

| Class IV CHF | Ischemia | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (1.8%) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.07–12.4 | 0.48 (0.66;0.14–3.09) | 0.57 (0.71;0.15–3.38) |

| No ischemia | 6 (3.9%) | 3 (1.7%) | 0.26 | 2.20 | 0.36–13.8 | |||

PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; MED = Medical Therapy Alone; MI = Myocardial Infarction; CHF = Congestive Heart Failure

Discussion

This analysis was conducted to determine the impact of pre-randomization stress testing on clinical outcomes in patients with persistent total occlusions of the IRA following myocardial infarction in OAT. The three main findings of the analysis were: i) study patients who underwent stress testing had better outcomes than those who did not; ii) mild-moderate inducible ischemia was not associated with any difference in outcomes; iii) the lack of clinical benefit for PCI over MED seen overall was consistent among subgroups regardless of whether stress testing was performed or inducible ischemia was present.

The higher event rates for patients who did not undergo pre-randomization stress testing in OAT is consistent with previous studies showing worse outcomes for patients unable to perform exercise testing12, 17. However, the higher event rate in OAT is most likely related to the differences in baseline clinical characteristics and left ventricular function. The OAT protocol did not require pre-randomization stress testing for patients with akinesis/dyskinesis of the infarct zone (unless multivessel disease was present). Not surprisingly, patients who underwent stress testing were younger, had less ST elevation and loss of R-waves, were less likely to have LAD as the IRA, had lower heart rates and higher ejection fractions. The patients who underwent pre-randomization stress testing were therefore a lower risk cohort with smaller infarct size and more preserved left ventricular function.

Previous studies, including the DANAMI trial, have demonstrated that patients with severe inducible ischemia early after MI benefit from revascularization1, albeit in a period before the modern era of optimal medical therapy. It is unclear whether patients with only mild-moderate or delayed inducible ischemia after MI derive benefit from revascularization,. In the COURAGE trial, there was no benefit of PCI compared with optimal medical therapy in the 876 patients with previous myocardial infarction and objective evidence of ischemia on stress testing18. Patients with early markedly positive stress tests were excluded from COURAGE. The use of anti-anginal medications, aspirin, and ACE-inhibitors in OAT was similar to COURAGE, with the exception of lower use of calcium-channel blockers4, 18. In this analysis, PCI showed no benefit over MED for OAT patients with mild-moderate ischemia on pre-randomization stress testing. One potential explanation for the lack of benefit with PCI is that mild-moderate inducible ischemia does not help identify a subset of higher-risk patients who would benefit from revascularization. This is supported by the absence of any significant relationship between inducible ischemia and clinical outcomes on univariate or multivariate testing in this analysis. Furthermore, for patients undergoing PCI for persistent total occlusion of the IRA, any potential benefit may be offset by the risk of distal embolization leading to periprocedural MI and the loss of rapidly recruitable collateral flow, increasing the risk for subsequent ischemic events if restenosis or reocclusion occurs. The results of this analysis, along with the main OAT results, indicate that patients with persistent occlusion of the IRA and no post-MI angina at rest or severe inducible ischemia should be treated medically, which is consistent with the revised ACC/AHA and ESC guidelines19, 20.

In contrast to other previous studies5, 6, 11, we did not demonstrate any relationship between the presence of inducible ischemia and clinical outcomes in this analysis. Since patients with severe inducible ischemia were ineligible for the trial, this analysis only evaluated patients with mild-moderate ischemia. Several studies have shown that only severe inducible ischemia is associated with worse outcomes after MI7, 8, 10. The COURAGE nuclear substudy demonstrated confirmed the relationship between ischemia in >10% of the LV and increased risk of events, and suggested that revascularization may benefit this group 21. In OAT, mild-moderate inducible ischemia was documented in 40% of patients who underwent pre-randomization stress testing, but was not related to prognosis. It is possible that inducible ischemia after MI is only associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with patent IRA. The presence of inducible ischemia in the IRA territory was not associated with higher rates of non-protocol (cross-over) PCI that may have confounded our ability to identify a relationship between inducible ischemia and outcomes.

Although these results indicate that the presence of mild-moderate inducible ischemia in this patient population does not provide prognostic information or an indication for PCI of a persistently occluded IRA, stress testing may still be warranted after myocardial infarction to rule out severe inducible ischemia. Previous studies and the recent COURAGE substudy suggest the possibility that patients with severe inducible ischemia after MI may benefit from revascularization1, 7, 8, 10, 21.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Stress testing was performed in only 27% of patients in OAT. The possibility that this study is underpowered to identify a significant association between ischemia and outcomes cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, this is the largest study to date to the impact of inducible ischemia on outcomes for patients with persistently occluded IRA undergoing PCI or receiving optimal medical therapy. The type of stress testing was based on local clinical practice. The majority of patients in this analysis underwent only low-level exercise testing without radionuclide or echocardiographic imaging. Given the lower sensitivity of low-level exercise testing, it is possible that the number of patients with inducible ischemia was underestimated. However, this would not alter the observed lack of benefit of PCI over MED, since there was no signal of benefit and possibly a trend toward higher event rates with PCI irrespective of whether inducible ischemia was documented. The presence and localization of inducible ischemia in the IRA territory vs. non-IRA territory was based on site interpretation. The ability of sites to accurately localize ischemia may have been limited by the low use of radionuclide or echocardiographic imaging. However, since 82% of patients who underwent stress testing had single vessel disease, the localization of ischemia to the IRA territory should have been correct in the vast majority of cases. The anti-anginal medications taken at the time of stress testing were not documented. The findings of this analysis apply only to patients with persistent total occlusion of the IRA after MI and without severe inducible ischemia or post-MI angina at rest.

Conclusions

In OAT, patients who underwent stress testing had better outcomes than patients who did not, likely related to differences in age and LV function. In patients managed with optimal medical therapy or PCI, mild-moderate inducible ischemia was not related to clinical outcomes. The lack of benefit for PCI over MED was consistent regardless of whether stress testing was performed or mild-moderate inducible ischemia was present.

Acknowledgments

We thank the investigators and the staff at the study sites for their important contributions, Zubin Dastur and Erika Laurion for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

The project described was supported by Award Numbers U01 HL062509 and U01 HL062511 from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Madsen JK, Grande P, Saunamaki K, Thayssen P, Kassis E, Eriksen U, et al. Danish multicenter randomized study of invasive versus conservative treatment in patients with inducible ischemia after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction (DANAMI). DANish trial in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 1997;96(3):748–55. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welty FK, Mittleman MA, Lewis SM, Kowalker WL, Healy RW, Shubrooks SJ, et al. A patent infarct-related artery is associated with reduced long-term mortality after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for postinfarction ischemia and an ejection fraction <50% Circulation. 1996;93(8):1496–501. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.8.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Knatterud GL, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Mark DB, et al. Design and methodology of the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) Am Heart J. 2005;150(4):627–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Reynolds HR, Abramsky SJ, et al. Coronary intervention for persistent occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2395–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBusk RF, Haskell W. Symptom-limited vs heart-rate-limited exercise testing soon after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1980;61(4):738–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Froelicher VF, Perdue S, Pewen W, Risch M. Application of meta-analysis using an electronic spread sheet to exercise testing in patients after myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 1987;83(6):1045–54. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kishida H, Hata N, Kanazawa M. Prognostic value of low-level exercise testing in patients with myocardial infarction. Jpn Heart J. 1989;30(3):275–85. doi: 10.1536/ihj.30.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krone RJ, Miller JP, Gillespie JA, Weld FM. Usefulness of low-level exercise testing early after acute myocardial infarction in patients taking beta-blocking agents. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60(1):23–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90977-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mark DB, Hlatky MA, Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Califf RM, Pryor DB. Exercise treadmill score for predicting prognosis in coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106(6):793–800. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-6-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson R, Umachandran V, Ranjadayalan K, Wilkinson P, Marchant B, Timmis AD. Reassessment of treadmill stress testing for risk stratification in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by thrombolysis. Br Heart J. 1993;70(5):415–20. doi: 10.1136/hrt.70.5.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theroux P, Waters DD, Halphen C, Debaisieux JC, Mizgala HF. Prognostic value of exercise testing soon after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(7):341–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908163010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villella A, Maggioni AP, Villella M, Giordano A, Turazza FM, Santoro E, et al. Prognostic significance of maximal exercise testing after myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic agents: the GISSI-2 data-base. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza Nell’Infarto. Lancet. 1995;346(8974):523–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Underwood SR, Anagnostopoulos C, Cerqueira M, Ell PJ, Flint EJ, Harbinson M, et al. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy: the evidence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31(2):261–91. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation form incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:453–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35(1):1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972;34(2):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newby LK, Califf RM, Guerci A, Weaver WD, Col J, Horgan JH, et al. Early discharge in the thrombolytic era: an analysis of criteria for uncomplicated infarction from the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and t-PA for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27(3):625–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, et al. Optimal Medical Therapy with or without PCI for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King SB, 3rd, Smith SC, Jr, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, Jacobs AK, Morrison DA, Williams DO, et al. 2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: 2007 Writing Group to Review New Evidence and Update the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Writing on Behalf of the 2005 Writing Committee. Circulation. 2008;117(2):261–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, Mancini GB, Hayes SW, Hartigan PM, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117(10):1283–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]