Abstract

To facilitate effectiveness testing and dissemination of treatments to community based setting, therapist training manuals that are more “community friendly” are needed. The aim of the current project was to create revised versions of individual drug counseling (IDC) and group drug counseling (GDC) treatment manuals for cocaine dependence and to conduct a preliminary study of their effectiveness. After changing the format and context of existing drug counseling manuals to have greater ease of use in the community, draft manuals were given to 23 community-based counselors for their feedback. Final versions were then used in a pilot randomized clinical trial involving 41 cocaine dependent patients who received 3 months of either IDC + GDC or GDC alone treatment. Counselors implemented the new treatment manuals with acceptable levels of adherence and competence. Outcome results indicated that substantial change in drug use was evident, but the amount of abstinence obtained was limited.

Keywords: Cocaine dependence, drug counseling, randomized trial

I. Introduction

Cocaine dependence is a serious disorder that remains an ongoing public health concern. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH, 2007) reported that 1,671,000 people abused or had a dependence on cocaine and an estimated 928,000 persons received treatment for cocaine in 2006. Cocaine use and dependence has a large impact on both the individual and society. One study detected recent cocaine use at autopsy in 18% of young adult victims of fatal injuries in a 2-year period in New York City (Marzuk et al., 1995). A 2006 Centers for Disease Control report revealed that cocaine use was detected at autopsy in 9.4% of suicide victims in 13 states who were given toxicology tests (Karch, Crosby, & Simon, 2006). Additionally, a significant positive association has been found between use of cocaine, particularly crack cocaine injection, and HIV and AIDS infection (Tashkin, 2004). Studies have reported correlations between crack cocaine injection and engaging in risky drug and sexual behaviors that can contribute to the contraction of sexually-transmitted diseases, including sharing needles and drug solutions, having multiple sex partners, exchanging sex for drugs and/or money, and having unprotected sex (Buchanan et al., 2006; Santibanez et al., 2005).

The development of successful treatments for cocaine use disorders therefore has the potential to have a significant impact on the health of cocaine users as well as the larger social problems (e.g., crime, HIV) associated with cocaine use. Moreover, successful treatment of cocaine dependence is likely to provide significant financial savings to society. Although cost numbers specifically for cocaine dependence are not available, one report (Harwood, Fountain, & Livemore, 1999) estimated that the costs of drug abuse and dependence in general in 1995 were $109.8 billion.

Treatment for cocaine dependency in drug abuse treatment facilities in the community almost always includes some form of drug counseling as part of the treatment package. In many programs, drug counseling is the only or primary intervention received by participating patients (Simpson, Joe, Fletcher, Hubbard, & Anglin, 1999). The standard model for drug counseling in the community is an abstinence based approach that relies upon the 12-Step (Alcoholics Anonymous and similar programs) philosophy, and this approach also has been specifically pursued for cocaine (Ehrlich & McGeehan, 1988). Many counselors have combined a relapse prevention approach with the standard 12-step philosophy (Washton, 1989), and programs that offer drug counselors training with formal certification in relapse prevention now exist. While the traditional 12-Step philosophy primarily focuses on the “people, places, and things” that should be avoided because of their association with drug use, the relapse prevention approaches make use of concepts and techniques from cognitive-behavioral psychotherapies, including skills training and the role of expectations, irrational thoughts, feelings, and self-defeating behaviors, in order to help the patient cope with cravings and prevent or reduce relapses.

While drug counseling is the most widely practiced treatment in the addictions community, most clinical trials have focused on treatments administered by professionals. Although it will remain important to examine psychosocial treatments delivered by highly trained professional particularly in the early stages of the development of new modalities, the dominance of drug counselors as the front-line clinicians within the addiction service delivery system suggests that treatments that can be tested and disseminated to such drug counselors will have greater impact on the delivery of addiction services.

In addition to examining the dissemination of a particular treatment to drug counselors, it is imperative to parse out and standardize the treatment techniques which are most effective within the addictions field. Although some version of 12-step oriented drug counseling is already widely practiced in the community, some approaches are not standardized and it is unclear what types of counseling techniques are most useful. The development and dissemination of an efficacious manual-based drug counseling approach would potentially allow for improved quality control and better treatment outcome of drug counseling within the community.

In the multicenter National Institute on Drug Abuse Cocaine Collaborative Study (NIDA CCTS; Crits-Christoph et al., 1997; Crits-Christoph et al., 1999), manual-based individual drug counseling (IDC) plus group drug counseling (GDC) was found to be more effective than GDC alone, or individual cognitive or supportive-expressive therapy plus concurrent GDC. This result, coupled with the widespread reliance on drug counseling in substance abuse treatment centers, raises the following question: Can a “community friendly” version of a manual-based drug counseling manual be developed that would allow evaluation of manual-based drug counseling in community settings and eventual dissemination of a standardized version of drug counseling? If so, would a “community-friendly” version of drug-counseling yield comparable outcomes to the original model developed and tested within the context of an academic-based clinical trial?

The current study was an effort to develop revised versions of manual-based community-friendly IDC and GDC and conduct a feasibility study on the use of these manuals. The aims of the study were to determine the acceptability to clinicians and patients of the new treatments, to determine whether community counselors can be trained to adequate levels of adherence/competence in implementing the new IDC and GDC treatments, to obtain preliminary data on whether the new community-friendly IDC + GDC package produces superior retention and outcomes compared to GDC alone, and to compare the results from this study to the full model of drug counseling treatment examined in the NIDA CCTS. Although the eventual goal of this research program is to implement the “community friendly” manuals in actual community agencies, as a preliminary step we brought community clinicians into an academic-bases setting to evaluate their reactions to the new manuals, ability to learn the manuals, and preliminary outcomes in implementing the treatments. This approach allowed us to evaluate the treatment manuals without the constraints of the “real world” realities of the administrative and financial pressures that might bear on clinicians’ interest in learning a new manual, ability to learn, and treatment outcomes that would occur in a community clinic.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Cocaine dependent subjects were recruited through approved advertisements and through referrals within the department of psychiatry of a large urban medical center. Our goal was to obtain 40 patients (20 in each treatment group); we recruited 41 patients. Patients were eligible to receive treatment if they had a principal diagnosis of current Cocaine Dependence or Cocaine Dependence in Early Partial Remission as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1994), which was determined from a 0 to 8 severity rating scale adapted from the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule- Revised (ADIS-R; DiNardo & Barlow, 1988). Patients had to be between 21 and 60 years of age, and have used cocaine at least once in the past 30 days. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a diagnosis of Current Opioid Dependence or Opioid Dependence in Early Partial Remission, dementia or other irreversible organic brain syndrome, current imminent suicide risk (3 or greater on item 3 of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960), current significant homicide risk, life threatening or unstable medical illness, a medical illness that can create a marked change in mental state, or any neurological, psychiatric, or medical disorder other than a movement disorder that may interfere with cerebral function or blood flow. Additionally, patients could not participate if they were positive for psychotic symptoms, were pregnant or nursing, were currently mandated for treatment by the legal system, or on house arrest. All patients enrolled provided informed consent and the protocol was reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Assessment measures

2.2.1. Diagnostic assessment

The Structured Clinical Interview, Patient Version (SCID-P) for DSM-IV (First et al., 1994) was used to assess Axis I diagnostic status. The diagnostic assessment was administered by trained diagnostic and clinical evaluators who were doctoral or masters’ level psychologists or social workers.

2.2.2. Urinalysis

Urine specimens were collected weekly throughout treatment under staff observation and screened for illicit opioids, benzyolecognine (a cocaine metabolite), amphetamines, methamphetamines, and benzodiazepines using an on-site analysis system. Urine results were included as part of a composite cocaine use measure.

2.2.3. Cocaine Inventory

This scale was modified for the NIDA CCTS from an unpublished measure originally designed by Bristol-Meyers Squibb and later used by Gawin et al. (1989). The inventory asks questions about how many times the patient has used cocaine or other drugs in the last week, how much money was spent on cocaine in the last week, and the method of administration. The cocaine inventory was administered at baseline, weekly throughout treatment (at treatment visits), and at assessment visits conducted 1, 2, and 3 months post-baseline.

2.2.4. The Addiction Severity Index

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI; 5th Edition; McLellan et al., 1992) is a structured interview that assesses the patients’ past and current (last 30 days time period) functioning in seven target areas: medical status, employment status, alcohol use, drug use, legal status, psychiatric status, and family/social relationships related to substance use. Test-retest reliability of 0.83 or higher is reported on all scales (McLellan, Luborsky, Cacciola, & Griffith, 1985). The Drug Use composite of the ASI was the primary outcome measures. The other ASI scales were included as secondary/exploratory measures of outcome. The ASI was administered by trained research assistants at baseline and at assessments conducted 1, 2, and 3 months post-baseline.

2.2.5. Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression Rating Scale

The 24-item version of the widely used Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960) was administered utilizing the Structured Interview Guide (SIGH-D; Williams, 1988). The HAM-D was administered by trained research assistants at baseline and months 1, 2, and 3.

2.2.6. Risk Assessment Battery

The Risk Assessment Battery (RAB; Metzger et al., 1992) is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess high-risk behaviors associated with HIV transmission. The measure yields two scores: Drug Risk Behavior (e.g. sharing needles, IV drug use) and Sex Risk Behavior (e.g., exchanging sex for drugs, unprotected sexual activity). Preliminary reliability and validity data have indicated good agreement between interview and RAB responses on the same items and adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability of 0.75 to 0.88. High scores on the measure have been found to predict development of HIV positive status over a year and a half period (Metzger et al., 1992). The RAB was administered at baseline and at 3 months.

2.2.8. Acceptability of Treatment Questionnaire

We examined acceptability to patients of the new treatments using a questionnaire developed for this study. The questionnaire was administered at session 2 and again at termination of treatment. Patients gave their reactions to the treatment by rating 7 items (on a 1 to 5 scale from “never” to “very often”) that asked whether the treatment was coherent, clear, and not confusing to them.

2.2.9. Follow-Up Assessments

Follow-up assessments were conducted at 1, 2, and 3 months post-baseline using the instruments described above. Follow-up assessment were conducted in person, with trained research assistants responsible for the interviews and collection of self-report and urines. As with the weekly urines collected during treatment, urines at the follow-up visits were screened for illicit opioids, benzyolecognine (a cocaine metabolite), amphetamines, methamphetamines, and benzodiazepines using an on-site analysis system. Follow-up assessments were scheduled regardless of whether patients were currently in treatment.

2.3. Drug counseling interventions

Treatments were 3 months in duration. IDC sessions were held twice/week for the first month and then once/week for the remaining two months. GDC sessions were held once/week for the 3 months (12 sessions total). Individual counseling sessions were 50 minutes long; group sessions were 1.5 hours long.

The revised IDC manual (Mercer & Woody, 2004) was adapted from the original IDC manual of Mercer and Woody (1999) used in the NIDA CCTS. The original IDC manual is available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/TXManuals/IDCA/IDCA1.html. IDC is time-limited and focuses primarily on helping the client achieve and maintain abstinence by encouraging behavioral changes, such as avoiding triggers and structuring one’s life. Drug counseling techniques in the manual are consistent with the philosophy of the 12-step approach, specifically that addiction is a disease that damages the person physically, emotionally and spiritually and that recovery is a gradual process. Participation in self-help groups is strongly encouraged. Three modifications were made to the original IDC manual to make it more “community friendly.” The first was to incorporate relapse prevention techniques that focus on thoughts and beliefs about addiction. The second was to provide some guidance for handling psychiatric comorbidity in cocaine using patients. The third was to limit the treatment to 3 months duration rather than 6 months.

The revised GDC treatment manual (Mercer & Daley, 2004) was similarly adapted from the original GDC manual (Daley, Mercer, & Carpenter, 1998) used in the NIDA CCTS. This 3-month group program is designed to educate clients about the important concepts in addiction recovery, strongly encourage participation in 12-step programs and provide a supportive group atmosphere in which members can express feelings, discuss problems and learn to draw strength from one another. Groups were open for new members on a rolling basis. The primary modification to the original GDC manual included shortening the treatment to 3 months and incorporating relapse prevention techniques.

Both the revised IDC and revised GDC manuals were given to 23 community-based drug counselors for feedback. Counselors were asked to read the manuals, comment on their ease of use in their community-setting, and provide open-ended comments. Suggestions from the counselors were then incorporated into the manuals to arrive at a final version.

2.3.1. Counselor selection and training

Experienced counselors were recruited from the community to participate. Selection procedures included review of applicant education, background, and clinical experience. Counselors participated in the current project on a fee-for-service basis. Once accepted into a study, counselors were given a copy of the relevant treatment manual and other training materials to review. There were two master’s level counselors who administered GDC treatment, one with a master’s in social work and the other with a license in professional counseling, who was also the GDC supervisor throughout the study. There were two bachelor’s level counselors who implemented the IDC treatment program, one with over 15 years of drug counseling experience who also functioned as the IDC supervisor, and the other with over 5 years of experience working as a counselor with individuals with substance use disorders.

2.3.2. Audiotaping and assessment of treatment fidelity

All IDC treatment sessions were audiotaped. All GDC treatment sessions were audiotaped and videotaped. These tapes were rated for counselor adherence and competence to the treatment manuals using adaptations of existing scales (additional items added to cover new techniques added) for the evaluation of IDC and GDC (Mercer, Carpenter, & Daley, 1994; Barber, Mercer, Krakauer, & Calvo, 1996).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of sample

Table 1 provides baseline demographic and clinical data on the sample. Forty-one patients (31 male; 10 females) agreed to participate in the study. In terms of ethnicity, 4 patients identified themselves as white, 35 as African American, and 2 as Other. The average age of patients was 42.4 years with an average of 12.7 years of education. Overall 18 patients (44%) were employed, 31 patients (76%) lived alone, 29 patients (71%) were crack users, and the average days of cocaine use in the month prior to treatment was 12.7 days.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Sample (N=41)

| Treatment group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| IDC + GDC | GDC | Total | |

| Characteristics | n=20 | n=21 | n=41 |

| % Non-minority (#) | 5 (1) | 14 (3) | 10 (4) |

| % Employed (#) | 45 (9) | 43 (9) | 44 (18) |

| % Living Alone (#) | 80 (16) | 71 (15) | 76 (31) |

| % Crack & Injectors (#) | 70 (14) | 71 (15) | 71 (29) |

| % Male (#) | 85 (17) | 67 (14) | 76 (31) |

| Age- Mean (SD) | 44.7 (5.4) | 40.2 (8.7) | 42.4 (7.6) |

| Years Education, Mean (SD) | 13.2 (2.1) | 12.2 (0.9) | 12.7 (1.7) |

| ASI Drug Comp., Mean (SD) | 0.25 (0.07) | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.24 (0.07) |

| Days Cocaine Past 30 at screening, Mean (SD) | 12.3 (8.2) | 13.1 (8.5) | 12.7 (8.3) |

| Years cocaine use, Mean (SD) | 12.5 (7.8) | 10.4 (6.9) | 11.4 (7.3) |

| Days Alcohol Past 30, Mean (SD) | 9.3 (9.0) | 5.2 (6.1) | 7.2 (7.9) |

| ASI Psych Composite, Mean (SD) | 0.20 (0.19) | 0.23 (0.22) | 0.21 (0.21) |

| Intake HAMD score (17-item), Mean (SD) | 9.4 (6.1) | 10.5 (8.4) | 10.0 (7.3) |

3.2. Acceptability of Treatment

Acceptability was examined by the Acceptability of Treatment questionnaire. Responses from the questionnaire indicated that patients felt the treatments/counselors were not confusing (M = 1.4, SD = 0.80), did not send mixed message about whether one should take control of one’s addiction or give up control to a “higher power” (M = 1.2.; SD = 0.59), were clear (M = 4.3; SD = 1.17), presented a coherent model of addiction and treatment (M = 4.2; SD = 1.20), were sensible (M = 4.4; SD = 1.08), and did not have elements that were non-understandable (M = 1.6; SD = 1.00) (all of these means were in the favorable direction on the 1 to 5 scale). One item (“My counselor uses a variety of unrelated techniques in sessions”) was rated in the middle of the scale (M = 2.3, SD=1.45), suggesting that, to some extent, that unrelated techniques were used during sessions, but this mixing of techniques did not confuse patients.

3.3. Attrition

Attrition rates after randomization and by study month are given in Table 2. Overall, attrition was high, with half of patients in the IDC + GDC group and 62% of those in the GDC group dropping out of treatment in the first month. All patients had dropped out of treatment by 3 months.

Table 2.

Number (%) of Patients who Dropped Out of Treatment

| Treatment Group | Randomized No Shows | Prior to Month 1 Assessment | Prior to Month 2 Assessment | Prior to Month 3 Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDC + GDC (n=20) | 1 (5%) | 10 (50%) | 15 (75%) | 20 (100%) |

| GDC (n=21) | 3 (14%) | 10 (62%) | 20 (95%) | 21 (100%) |

3.4. Counselor adherence/competence

Adherence/competence ratings made by the clinical supervisor were available for 14 of the 20 patients who received IDC (the other 6 cases were treated by the supervisor/expert). Selecting session 2 and one additional session between 3 and 10 (chosen randomly), we compared ratings of adherence and competence (average of 34 items each) for the 14 patients in the current study. Each item on these scales is rated on a 1 to 7 scale. The average adherence in the current study (M = 3.8, SD = 0.36) and the average competence (M = 3.9; SD =0.29) were high. The average level of adherence by the GDC counselor to GDC techniques was also very high (M = 6.2; SD = 0.37), with over 44 group sessions rated spanning the duration of the project.

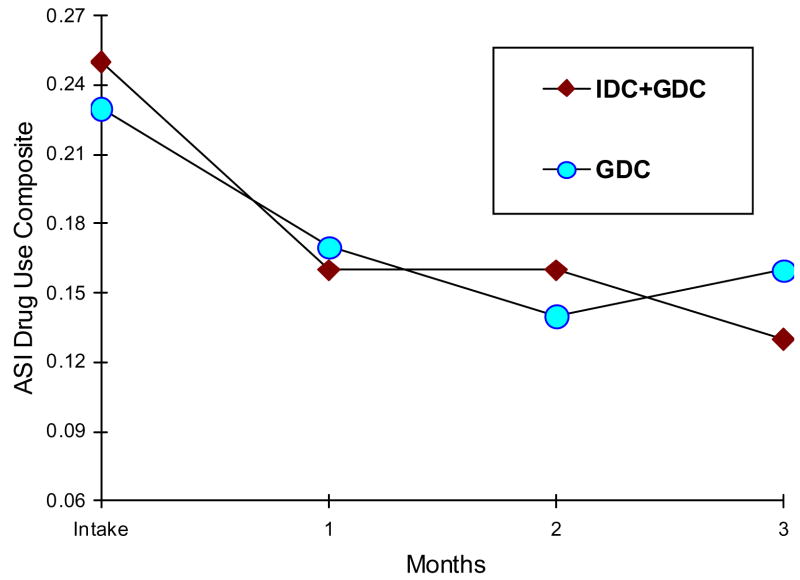

3.5. ASI Outcomes

The primary efficacy measure was the ASI Drug Use Composite. The ASI Drug Use Composite scores are given in Figure 1. Overall, both groups improved during the 3 month treatment period. ASI Drug Use scores decreased from 0.25 (SD = 0.07) (IDC + GDC) and 0.23 (SD = 0.07) (GDC) to 0.13 (SD= 0.08) and 0.16 (SD = 0.10), respectively.

Figure 1.

ASI drug use composite scores over 3 months of treatment.

3.6. Abstinence

Abstinence was evaluated using a composite abstinence measure integrating data from urines, ASI, and cocaine inventory. The measure was scored as “abstinent” or “not abstinent” on a monthly basis based on any indication of cocaine use across the three measures.

In the IDC + GDC group, 17 patients (85%) never achieved a full month of abstinence from cocaine. One patient (5%) achieved one month of abstinence and 2 patients (10%) achieved two consecutive months of abstinence from cocaine in the IDC + GDC group. For the GDC alone group, 13 patients (62%) failed to achieve a single month of abstinence, 5 (24%) achieved one month of abstinence, 2 (10%) achieved two consecutive months of abstinence, and 1 (5%) achieved 3 consecutive months of abstinence from cocaine.

3.7. Other Secondary Outcomes

Results for secondary outcome measures are given in Table 3. On all measures, there was improvement over time. With the limited sample size, no comparisons of the treatment groups reached statistical significance. However, there was a tendency for the -IDC + GDC group to fare better on measures of psychiatric severity. At 3 months, the effect size (Cohen’s d) for IDC + GDC vs. GDC was 2.5, a very large effect.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) Scores on Secondary Outcome Measures at Baseline and Month 3

| Variable | Treatment group | Baseline M (SD) | Month 3 M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASI-Alcohol | IDC + GDC | 0.30 (0.24) | 0.18 (0.19) |

| GDC | 0.19 (0.24) | 0.18 (0.24) | |

| ASI-Family | IDC + GDC | 0.37 (0.35) | 0.27 (0.27) |

| GDC | 0.23 (0.23) | 0.21 (0.24) | |

| ASI-Legal | IDC + GDC | 0.10 (0.18) | 0.11 (0.18) |

| GDC | 0.06 (0.17) | 0.06 (0.16) | |

| ASI-Medical | IDC + GDC | 0.06 (0.11) | 0.34 (0.34) |

| GDC | 0.13 (0.13) | 0.48 (0.40) | |

| ASI-Employ | IDC + GDC | 0.61 (0.24) | 0.65 (0.22) |

| GDC | 0.60 (0.36) | 0.70 (0.37) | |

| ASI-Psych | IDC + GDC | 0.20 (0.19) | 0.11 (0.16) |

| GDC | 0.23 (0.22) | 0.16 (0.24) | |

| HAMD | IDC + GDC | 9.4 (6.1) | 4.9 (4.5) |

| GDC | 10.5 (8.4) | 7.3 (8.0) | |

| Risk Assessment | IDC + GDC | 5.7 (2.4) | 4.8 (3.8) |

| Battery | GDC | 4.6 (3.3) | 3.8 (2.9) |

3.8. Treatment Length in Relation to Reduction in Drug Use

Within the GDC group (n = 18), there was a non-significant correlation (r = −0.07, p = 0.80) between the number of group counseling sessions attended and average ASI Drug Use composite score during months 1 to 3, controlling for baseline ASI Drug Use composite scores. Within the IDC + GDC group, however, there were significant correlations between the number of group sessions attended (r = −0.50, p = 0.04) and average ASI Drug Use composite during months 1 to 3, and the number of individual sessions attended (r = −0.59, p = 0.01) and average ASI Drug use composite during months 1 to 3 (in both cases, controlling for baseline ASI Drug Use composite scores).

3.9. Comparison to the NIDA CCTS

Our current patient sample was more severe than the sample in the NIDA CCTS. Duration of cocaine use was longer (about 11 years, compared to 7 years in the NIDA CCTS; t (43) = 3.83, p = 0.0004; DF based on Satterthwaite’s correction for heterogeneity of variances); days of cocaine use in the past 30 days at screening was higher (about 12.7 vs. 10.4; t (526) = 1.77, p = 0.08). However, ASI Psychiatric Severity Composite scores (0.21 vs. 0.19; t (526) = 0.70, p = 0.47.); HAM-D scores (10.0 vs. 8.9; t (44) = 0.87, p = 0.39), and ASI Drug Use Composite scores (about 0.24; t (526) = −0.09, p = 0.93.) were not significantly different in the two samples. The current sample was older (42 years vs. 34 years; t (526) =8.18, p < 0.0001), and largely minority (African American), with about 10% of the sample white (vs. 58% in the previous study; χ2 (1) = 35.31, p < 0.0001). Fewer patients in the current study were employed (44% vs. 60%; χ2 (1) = 4.20, p = 0.04).

Overall attrition rates in this study were higher than the NIDA CCTS. In the NIDA CCTS, 36% in IDC+GDC and 32% in GDC dropped out in the first month, compared to half of the patients dropping out in the first month in the current study (χ2 (1) =2.75, p = 0.10 for comparing the IDC + GDC groups in the two studies; χ2 (1) = 7.09, p = 0.008 for comparing the GDC alone groups in the two studies).

We also compared ratings of adherence and competence (average of 34 items that were in common between the measures used in the two studies) for the 14 patients in the current study with 98 patients in the NIDA CCTS. The average adherence in the current study (M = 3.8, SD = 0.36) was actually significantly (p < .0001) higher than that in the NIDA CCTS (M = 2.4, SD = 0.39). Average competence ratings were similar in the two studies (3.9 vs. 4.0, respectively).

ASI Drug Use outcomes in the current study were not significantly different from those obtained in the NIDA CCTS. In the NIDA CCTS, the IDC + GDC group decreased from 0.25 to 0.10 at 3 months on the ASI Drug Use composite; the GDC group decreased from 0.24 to 0.13 (F [2, 97] =0.71, p = 0.40 for IDC contrast and F [2, 102]=0.93, p = 0.33 for GDC contrast). However, it is important to note that in the NIDA CCTS treatment extended to 6 months and patients continued to improve. The end of treatment ASI Drug Use composite mean score for the IDC + GDC group at 6 months was 0.11, and was 0.13 for the GDC group in the NIDA CCTS. These 6 month scores are 20% and 16%, respectively, lower than the 3 month means for IDC + GDC and GDC alone in the current study, although the differences between the 6- month outcomes of the NIDA CCTS and the 3-month outcomes of the current study were not statistically significant for either the comparison of the IDC + GDC groups in the two studies (F [1, 104] = 1.21, p = 0.27) or the GDC alone groups in the two studies (F [1, 108] = 1.65, p = 0.20).

Examination of abstinent rates, however, revealed lower efficacy of IDC + GDC and GDC alone in the current study compared to IDC + GDC and GDC alone in the NIDA CCTS. In the NIDA CCTS, 71% of patients who received IDC+GDC compared to 15% for IDC + GDC in the current study (χ2 (1) = 23.2, p < 0.0001), and 58% of those who received GDC alone compared to 38% for GDC alone in the current study (χ2 (1) = 2.79, p = 0.10) achieved 1 month of abstinence on the composite cocaine abstinence measure. Rates of achieving 3 consecutive months of abstinence for IDC + GDC (38%) and GDC alone (27%) in the NIDA CCTS were significant higher than in the current study (χ2 (1) = 11.29, p < 0.0001 and χ2 (1) = 4.84, p = 0.03, respectively).

4. Discussion

The results of the current pilot/feasibility study were mixed. The data suggest that the new IDC and GDC treatments were coherent, clear, and understandable to patients. In addition, counselors could be trained to delivery the treatments with high levels of adherence and competence. However, levels of attrition were high and outcome appeared less favorable than observed with the more extensive treatment model investigated in the NIDA CCTS.

The comparison between the current investigation and the NIDA CCTS, however, must be qualified by awareness of design differences between the two studies. In particular, the previous study employed an initial orientation phase of up to 14 days during which time patients were required to attend three clinic visits (one group session and two case management visits) before being randomized. Highly non-compliant patients during this orientation phase (likely poor outcomes) were therefore not enrolled in the NIDA CCTS, but the current study had no such orientation phase. Differences between the two studies may also relate to the nature of the samples. Lower rates of employment and higher rates of minority status were evident in the current study compared to the NIDA CCTS. These differences may explain the higher attrition rates in the current study, as both employment status and minority status have been found to predict attrition from substance abuse treatment (Agosti, Nunes, & Ocepeck-Welikson, 1996; McCaul, Svikis, & Moore, 2001).

One possible explanation of the higher counselor adherence in the current study compared to the NIDA CCTS is a rater effect (different raters were used for the two studies). However, this explanation seems unlikely given that no difference was evident in competence ratings between the two studies. More likely, the large and diverse group of counselors in the NIDA CCTS led to lower average adherence. Regardless of the explanation of the differences between samples, the absolute levels of adherence/competence were very good in the current study. Thus, we would expect that most community-based drug counselors could easily be trained to deliver these treatment models.

The very high rates of attrition found with the new drug counseling treatments deserve comment. In clinical practice, it is a common goal to attempt to retain patients in treatment and achieve three months of continuous abstinence. However, in the current study, 50 – 62% dropped out in month and no patients completed the full 3 months of treatment. Clearly, the drug counseling models investigated here as well as unstandardized drug counseling in the community, at least with a cocaine dependent population, are inadequate to achieve the clinical goal of 3 months of abstinence. Either this expectation should be modified or the relative inadequacy of drug counseling for achieving this goal should be explicitly acknowledged.

Despite the fact that outcomes and retention rates were relatively poorer in the current study compared to the NIDA CCTS, drug use was reduced over time in the current study. There was also a slight advantage numerically in drug use outcomes for IDC + GDC compared to GDC alone at 3 months, but this difference was not statistically significant with the limited sample size. On secondary outcome measures, there was a very large effect size for the superiority of IDC + GDC compared to GDC alone on improvement in psychiatric severity. The individual attention with IDC may be particularly important for patients with comorbid psychiatric problems. However, this hypothesis would need to be tested with a larger, adequately powered study. To the extent that this result of an advantage of combined individual and group drug counseling over group drug counseling is reliable, the current study replicates a finding of the NIDA CCTS (Crits-Christoph et al., 1999). This finding has clear relevance for community drug treatment agencies because group drug counseling alone is the most common form of treatment such community settings. But given the lack of statistical significance in comparing treatments, it is also important to acknowledge that the changes in drug use over time seen in the current study may actually have little to do with the specific treatment techniques themselves; rather, these effects may be due to the passage of time and non-specific effects. The significant correlations in the IDC + GDC group between number of individual and group sessions and drug use outcomes suggests that something about staying in treatment improves outcomes, at least for the combined individual and group drug counseling condition.

In general, though, the more modest outcomes for drug counseling treatments for cocaine dependence found in the current study, although inferior to outcomes in the NIDA CCTS, are consistent with other studies of drug counseling for cocaine dependence. For example, both Higgins et al. (1993) and Maude-Griffen et al. (1998) found that drug counseling was less efficacious than behavioral or cognitive-behavioral treatments for cocaine dependence.

Overall, these data indicate that while the revised IDC and GDC manuals are more compatible with community standards for content and length of treatment, these modifications come at a cost. Increasingly addiction is seen as similar to chronic illnesses that require ongoing, longer-term treatment (McLellan, McKay, Forman, Cacciola, & Kemp, 2005). Thus, while the new treatment models developed here allow for easier testing of drug counseling treatment within the context of the current service delivery system, evidence suggests that more intensive treatments (higher frequency) beyond what is typically offered in community settings may have greater effectiveness. In part, then, the value of the newly developed IDC and GDC manuals depends on one’s clinical and research goals. If an investigator requires a manual-based version of drug counseling treatments to conduct a research study within the context of the existing service delivery parameters of community agencies, the new IDC and GDC manuals may be of some value. Based on the current pilot study, however, it is not recommended that these manuals be currently used to guide clinical practice.

The primary limitation of the current study is that it was an initial pilot study with a limited sample size. The relatively small sample size limits statistical power for testing treatment group differences and increases the unreliability of any estimates of within-group or between-group effects due to sampling error. It is possible that different results would be obtained with a larger sample. Another limitation is that the sample was largely African-American male crack users. Generalizability of the results to patients with other demographic or clinical characteristics is unknown. A further limitation is that attrition was very high. While an inference can be made that those who drop out of treatment and likely to be continuing to use cocaine, the validity of this inference is not known for those patients who did not return for subsequent assessments. A final limitation is that only a limited number of drug counselors learned and conducted the new IDC and GDC treatments. It is possible that different results would have been obtained with other counselors. Future research is needed to test these new “community friendly” drug counseling manuals with a larger group of both patients and counselors, and to examine the usefulness of the manuals from both a clinical and research perspective in the context of community-based treatment of cocaine dependence.

In summary, the current pilot study indicates that new, community-friendly version of IDC and GDC can be successfully taught to drug counselors. However, outcome effects are very limited and attrition is high when such treatments are used for the treatment of cocaine dependence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported through the National Institute on Drug Abuse through grant R21-DA016002 (Paul Crits-Christoph, Principal Investigator). We wish to thank the counselors, supervisors, and patients who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agosti V, Nunes E, Ocepeck-Welikson K. Patient factors related to early attrition from an outpatient cocaine research clinic. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1996;22:29–39. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Mercer D, Krakauer I, Calvo N. Development of an Adherence/Competence Rating Scale for Individual Drug Counseling. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;43:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan D, Tooze JA, Shaw S, Kinzly M, Heimer R, Singer M. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, et al. The NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study: Rationale and Methods. Archives of General Psychiatry. 54:721–726. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, et al. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: Results of the NIDA Cocaine Collaborative Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:493–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Mercer D, Carpenter G. Group Drug Counseling Manual. Holmes Beach, FL: Learning Publications, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised (ADISR) Albany, NY: Phobia and Anxiety Disorders Clinic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich MA, McGeehan M. Cocaine recovery support groups and the language of recovery. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1988;17:11–17. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1985.10472313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders--Patient Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Kleber HD, Byck R, Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Jatlow PI. Desipramine facilitation of initial cocaine abstinence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:117–121. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810020019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood H, Fountain D, Livemore G. The economic costs of alcohol and drug abuse in the United States, 1992. 1999 doi: 10.1080/09652149933450. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.nida.hih.gov/economiccosts/intro.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foeg F, Badger G. Achieving cocaine abstinence with a behavioral approach. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:763–769. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch D, Crosby A, Simon T. Toxicology testing and results for suicide victims-13 States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2004;55:1245–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, Hirsch CS, Stajic M, Portera L, et al. Fatal injuries after cocaine use as a leading cause of death among young adults in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;29:1753–1757. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506293322606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude-Griffin PM, Hohenstein JM, Humfleet GL, Reilly PM, Tusel DJ, Hall SM. Superior efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for urban crack cocaine abusers: Main and matching effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:832–837. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul ME, Svikis DS, Moore RD. Predictors of outpatient treatment retention: patient versus substance use characteristics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;62:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith JE. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, McKay JR, Forman R, Cacciola J, Kemp J. Reconsidering the evaluation of addiction treatment: from retrospective follow-up to concurrent recovery monitoring. Addiction. 2005;100:447–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer D, Carpenter G, Daley D. The adherence and competence scale for group addiction counseling for TCACS. Center for Psychotherapy Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania Medical School; 1994. Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer D, Daley D. Community-Friendly Group Drug Counseling Manual. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Psychotherapy Research, University of Pennsylvania; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer D, Woody G. An Individual Drug Counseling Approach to Treat Cocaine Addiction: The Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study Model. National Institute on Drug Abuse, Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction Series. 1999 Retrieved 28 April 21, 2008, from http://www.drugabuse.gov/TXManuals/IDCA/IDCA1.html.

- Mercer D, Woody G. Community-Friendly Individual Drug Counseling. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Psychotherapy Research, University of Pennsylvania; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, DePhilippis D, Druley P, O’Brien CP, McLellan AT, Williams J, et al. The impact of HIV testing on risk for AIDS behaviors. Proceedings of the 53rd annual scientific meeting of the Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence, Inc..,; Richmond, Virginia. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Santibanez SS, Garfein RS, Swartzendruber A, Kerndt PR, Morse E, Ompad D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of crack-cocaine injection among young injection drug users in the United States, 1997–1999. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Fletcher BW, Hubbard RL, Anglin MD. A national evaluation of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:507–514. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2003). Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-22, DHHS Publication No. SMA 03–3836). Rockville, MD.

- Tashkin DP. Evidence implicating cocaine as a possible risk factor for HIV infection. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2004;147:26–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washton AM. Cocaine addiction: Treatment, Recovery, and Relapse Prevention. New York: W.W. Norton; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:742–727. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800320058007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]