Abstract

Purpose:

We examined sexual function in overweight and obese women with urinary incontinence, and evaluated the effects of an intensive behavioral weight reduction intervention on sexual function in this population.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 338 overweight and obese women reporting 10 or more incontinence episodes weekly were randomized to an intensive behavioral change (226) or structured education program (112) for 6 months. Sexual function was assessed using self-administered questionnaires. Multivariate regression was used to examine factors associated with baseline and 6-month change in sexual function as well as intervention effects.

Results:

Two-thirds of participants (233) were sexually active at baseline but more than half (188) reported low desire and a quarter (91) were sexually dissatisfied. More than half of sexually active participants (123) reported problems with arousal, lubrication, orgasm or incontinence during sex. Compared to controls women in the intervention group demonstrated a borderline increase in frequency of sexual activity at 6 months (OR 1.34, 95% CI 0.99–1.81, p = 0.06) but no differences in satisfaction (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.83–1.99, p = 0.26), desire (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.79–1.61, p = 0.52) or problems (β ± SE 0.03 ± 0.07, p = 0.68 for intervention effects on problems score). Neither clinical incontinence severity nor body mass index was independently associated with baseline or 6-month change in function (p >0.10 for all).

Conclusions:

Sexual dysfunction is common in overweight and obese women with incontinence but the severity of this dysfunction may not be directly related to the severity of incontinence or obesity. An intensive 6-month behavioral weight reduction intervention did not significantly improve sexual function in this population relative to controls.

Keywords: sexual behavior, urinary incontinence, obesity, weight loss

Urinary incontinence is a common problem in middle-aged and older women, with more than a third of women 40 years old or older reporting weekly or more frequent incontinence.1 In addition to other quality of life and functional limitations, many women with incontinence report dissatisfaction with sexual activity or other problems with sexual function.2 At this time it is not clear whether the sexual problems of women with incontinence are directly attributable to incontinence or are caused by comorbid factors.3,4 There are also few data to indicate whether clinical interventions directed at improving incontinence can also improve sexual function.5-7

Obesity is also a widespread problem in women with more than 20% in the United States meeting criteria for being overweight (BMI 25 to 29.9 kg/m2) and another 40% meeting criteria for being obese (BMI 30 kg/m2or greater).8 Although obesity has been shown to increase the risk of incontinence in women,9 there has been limited study of the impact of obesity on female sexual function10-12 and few trials of weight loss interventions in overweight or obese women have assessed the effects on sexual function.

We examined sexual function in a randomized controlled trial of an intensive behavioral weight reduction intervention in overweight and obese women with incontinence. In participants at baseline we identified clinical and contextual factors associated with decreased sexual activity and worse sexual function. We also assessed whether the intensive behavioral weight reduction intervention, which has been shown to produce weight loss and decrease incontinence relative to controls, was associated with greater improvement in sexual function in this population.13

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PRIDE study was a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a 6-month intensive lifestyle and behavioral change intervention vs a structured education program to promote weight loss in 338 overweight and obese women with incontinence.13 To be eligible women had to be at least 30 years old, have a BMI of 25 to 50 kg/m2 and self-report at least 10 episodes of incontinence weekly on a screening voiding diary. Women were excluded from study if they reported any condition that would prevent them from safely participating in an intensive diet and exercise program without medical supervision, or if they had undergone medical therapy for incontinence or weight loss in the previous month.13

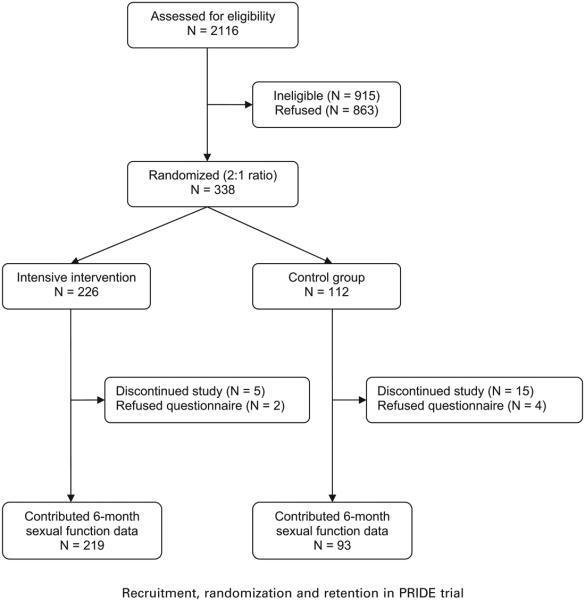

Participants were recruited from the local community at the Miriam Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island and the University of Alabama in Birmingham, and randomly allocated in a 2:1 ratio to the lifestyle and behavior change program (intervention 226) or to the structured education program (control 112) (see figure). With the exception of 3 staff members at the coordinating center who prepared analyses for the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, investigators and outcomes assessors were blinded to treatment assignment. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the institutional review boards at both clinical sites and the coordinating center approved all study procedures.

All study participants were given a self-help booklet which presented basic information about urge and stress incontinence, instructions for completing bladder diaries, information about performing pelvic floor muscle exercises and cognitive/behavioral strategies for managing urinary urgency. Women randomized to the control group were also assigned to participate in 1-hour group educational sessions at months 1, 2, 3 and 4, providing general information about weight loss, physical activity, healthy eating habits and health promotion (the structured education program).

Women in the intervention group were assigned to an intensive lifestyle and behavior change program modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program and Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) trials designed to produce an average loss of 7% to 9% of initial body weight by 6 months.14 This program included weekly 1-hour group sessions led by experts in nutrition, exercise and behavior change in which women were encouraged to increase physical activity to at least 200 minutes weekly using brisk walking or activities of similar intensity, and to record exercise time daily. Additionally, women were given a reduced calorie diet (1,200 to 1,500 kcal daily), offered sample meal plans modeling appropriate food selections and provided with vouchers for meal replacement products.

Frequency and clinical type of urinary incontinence were assessed at baseline and 6-month followup using 7-day self-report bladder diaries.13 Women were considered to have stress predominant incontinence if at least two-thirds of the incontinence episodes were identified as stress type (involuntary urine loss associated with coughing, sneezing, straining or exercise) and to have urge predominant incontinence if at least two-thirds of episodes were urge type (involuntary urine loss associated with a strong need or urge to void). The remaining women were considered to have mixed or other incontinence. Clinical incontinence severity was determined using a modified Sandvik Severity Index based on frequency of urine loss as well as the average amount of urine loss per episode (assessed using the question, “How much urine do you typically lose with each episode?” “Drops/small splashes/more”).15

Sexual function was assessed at baseline and at 6 months using self-administered questionnaires that participants completed in private and submitted to study personnel in sealed envelopes. Questionnaire items were drawn from the Female Sexual Function Index16 and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire17 but were adapted to assess sexual function in the 3 months before each visit. The questionnaire included several measures of overall sexual function that were administered to all participants regardless of sexual activity, as well as several measures to assess general and incontinence specific sexual problems among those who had been sexually active in the previous 3 months (Appendix 1). For the purposes of this study women were considered sexually active if they reported “any activity that is arousing to [them], including masturbation.”

Other variables assessed by self-report included demographic characteristics, reproductive history, menopausal history, history of hysterectomy and oophorectomy, and use of medications. Symptoms of depression were assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory, a self-administered screening instrument in which higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.18 Overall health status was assessed by asking participants to rate their general health as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. Body weight and height were measured for BMI calculation at baseline and at 6 months.

We examined associations between participant characteristics and self-reported sexual function outcomes at baseline using multivariable models. To assess overall sexual functioning outcomes measured on an ordinal scale (ie frequency of sexual activity, sexual desire and sexual satisfaction) we used GEE multinomial models, adjusting for clinical site and accounting for clustering within intervention groups.19 For sexual problems outcomes measured using multi-item summated scales (ie the “Urine leakage during sexual activity” and “Difficulties with sexual activity” scales), we treated the average value across scale items for each participant as a continuous outcome, and used GEE linear models to adjust for site and clustering within intervention groups.19 Only sexually active participants were included in models assessing sexual problems outcomes that were contingent upon activity. Age, race, partner status, parity, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, menopausal status, general health, depression symptoms, systemic estrogen use, SSRI use, clinical severity of incontinence, clinical type of incontinence, BMI and clinical site were included in all models.

We then examined the effect of the PRIDE intensive behavioral change vs structured education intervention on sexual functioning from the baseline to the 6-month visit. To adjust for clinical site and account for clustering within intervention groups we again used GEE multinomial models to assess outcomes measured using ordinal scales and linear models to assess outcomes measured using multi-item summated scales.19 In addition, we examined the relationship of change in frequency of incontinence and BMI to change in sexual function during 6 months using GEE multinomial or linear models as appropriate. All analyses were performed using SAS® statistical software version 9.1.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment assignment are summarized in table 1. The only statistically significant difference between treatment groups at baseline was a slightly higher average Beck Depression Inventory score in the control group (p = 0.03).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment assignment

| Intervention | Control | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD pt age | 53 ± 11 | 53 ± 10 | 0.91 |

| No. white race (%) | 171 (76) | 91 (81) | 0.20 |

| No. married/partnered (%) | 163 (72) | 86 (76) | 0.23 |

| Mean ± SD total live births | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 0.80 |

| No. hysterectomy (%) | 70 (31) | 29 (26) | 0.33 |

| No. bilat oophorectomy (%) | 30 (14) | 17 (15) | 0.65 |

| No. postmenopausal (%) | 115 (55) | 62 (58) | 0.67 |

| No. fair or poor self-reported health (%) |

20 (9) | 17 (15) | 0.08 |

| Mean ± SD Beck Depression Inventory score |

6.8 ± 5.1 | 8.8 ± 7.0 | 0.03 |

| No. current systemic estrogen use (%) |

21 (9) | 14 (13) | 0.24 |

| No. current SSRI use (%) | 40 (18) | 19 (17) | 0.87 |

| Mean ± SD physical examination: |

|||

| Wt (kg) | 98 ± 17 | 95 ± 16 | 0.77 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 37 ± 6 | 36 ± 6 | 0.97 |

| No. clinical type of incontinence (%): |

|||

| Stress predominant | 44 (20) | 31 (28) | 0.22 |

| Urge predominant | 104 (46) | 45 (40) | |

| Mixed or other | 78 (35) | 36 (32) | |

| No. clinical severity of incontinence (%): |

0.55 | ||

| Moderate | 23 (11) | 14 (14) | |

| Severe | 118 (58) | 51 (50) | |

| Very severe | 64 (31) | 38 (37) |

p Values for continuous data are from mixed linear regression, controlling for clinical site and correlation of outcomes in intervention groups. p Values for categorical data from generalized linear models proportional odds or multinomial models, controlling for clinical site and correlation of outcomes in intervention groups.

More than half of participants reported monthly or more frequent sexual activity at baseline and more than a quarter reported at least weekly sexual activity (table 2). Nevertheless, more than half described their level of sexual desire or interest as low to none and a quarter indicated that they were moderately or very sexually dissatisfied. There were no significant differences in sexual function by treatment group at baseline (p >0.10 for all).

Table 2.

Baseline sexual functioning of participants

| Intervention | Control | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. frequency of sexual activity (%):† | 0.75 | ||

| None in last 3 mos | 66 (30) | 34 (31) | |

| Less than monthly | 38 (17) | 17 (16) | |

| Monthly but not wkly | 58 (26) | 24 (22) | |

| Wkly but not daily | 58 (26) | 34 (31) | |

| Daily | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| No. overall sexual satisfaction (%):† | 0.36 | ||

| Very dissatisfied | 30 (14) | 22 (21) | |

| Moderately dissatisfied | 24 (11) | 15 (14) | |

| Equally satisfied/dissatisfied | 50 (24) | 19 (18) | |

| Moderately satisfied | 63 (30) | 27 (26) | |

| Very satisfied | 45 (21) | 23 (22) | |

| No. level of sexual desire (%):† | 0.64 | ||

| None | 32 (14) | 11 (10) | |

| Very low | 38 (17) | 26 (24) | |

| Low | 54 (24) | 27 (25) | |

| Moderate | 75 (33) | 37 (34) | |

| High/very high | 26 (12) | 9 (8) | |

| Mean ± SD leakage during sexual activity scale (1–5)‡,§ |

1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 0.29 |

| Mean ± SD difficulty with sexual activity scale (1–5)‡,§ |

2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 0.10 |

p Values for categorical data are from generalized linear models, controlling for clinical site and correlation of outcomes in intervention groups. p Values for continuous data are from ranked mixed linear regression, controlling for clinical site and correlation of outcomes in intervention groups.

Sexual function domains assessed among all randomized participants (226 intervention, 112 control).

Sexual problem scales assessed in sexually active participants only (158 intervention, 76 control).

Higher value on scale indicates worse function.

On multivariable analysis greater frequency of sexual activity was associated with availability of a partner (table 3). Women tended to report lower sexual satisfaction if they were postmenopausal, had more symptoms of depression or were using SSRIs. Higher sexual desire was associated with availability of a sexual partner and use of estrogen while lower sexual desire was associated with more symptoms of depression. Notably clinical incontinence severity, type of incontinence and BMI were not significantly associated with frequency of sexual activity, level of sexual desire or sexual satisfaction at baseline.

Table 3.

Predictors of sexual activity, sexual satisfaction and sexual desire among participants at baseline

| OR (95% CI)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Frequency of Activity |

Greater Overall Satisfaction |

Greater Level of Desire |

|

| Age (/5 yrs) | 0.84 (0.69–1.01) | 1.17 (0.96–1.43) | 0.87 (0.73–1.05) |

| White race | 1.53 (0.80–2.93) | 1.26 (0.69–2.31) | 0.69 (0.37–1.30) |

| Current partner | 5.51 (2.84–10.70)† | 1.41 (0.81–2.45) | 2.39 (1.31–4.35)† |

| Total live births | 1.02 (0.82–1.28) | 1.07 (0.88–1.30) | 1.05 (0.88–1.27) |

| Hysterectomy | 1.27 (0.58–2.78) | 1.12 (0.58–2.16) | 1.08 (0.46–2.54) |

| Oophorectomy (bilat) | 0.37 (0.13–1.10) | 0.73 (0.26–2.07) | 0.55 (0.26–1.19) |

| Postmenopausal | 0.66 (0.36–1.21) | 0.47 (0.23–0.98)† | 0.99 (0.53–1.86) |

| Poor–fair self-reported health | 0.98 (0.50–1.90) | 1.13 (0.56–2.28) | 0.87 (0.52–1.47) |

| Beck Depression Inventory score (/10 increase) | 0.67 (0.43–1.04) | 0.35 (0.24–0.52)† | 0.46 (0.33–0.65)† |

| Current estrogen use | 1.40 (0.56–3.50) | 1.52 (0.69–3.36) | 4.22 (1.68–10.58)† |

| Current SSRI use | 0.84 (0.46–1.53) | 0.43 (0.23–0.79)† | 0.87 (0.53–1.44) |

| Clinically severe incontinence | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) |

| Urge/mixed vs stress incontinence | 1.04 (0.58–1.88) | 1.19 (0.74–1.92) | 1.10 (0.67–1.80) |

| BMI (/5 kg/m2 increase) | 0.82 (0.65–1.02) | 0.94 (0.79–1.13) | 0.90 (0.72–1.13) |

Odds ratios are adjusted for all predictors as well as clinical site and account for clustering within intervention groups.

p ≤0.05.

Women who were sexually active at baseline (233) were more likely to report that urine leakage interfered with sexual activity if they were younger, post-menopausal or had more severe symptoms of depression after adjusting for other characteristics (table 4). Sexually active women were also more likely to report other sexual difficulties if they did not have a partner, were postmenopausal, had more symptoms of depression or were using SSRIs. Estrogen use was associated with fewer difficulties. Clinical incontinence severity, type of incontinence and BMI were not associated with performance on either problem scale.

Table 4.

Predictors of sexual problems among sexually active women at baseline

| Urine Leakage During Sexual Activity |

Other Problems With Sexual Activity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI)* | p Value | B (95% CI)* | p Value | |

| Age (/5 yrs) | −0.09 (−0.18–−0.01) | 0.02 | 0.01 (−0.06–0.09) | 0.71 |

| White race | −0.10 (−0.40–0.20) | 0.52 | −0.16 (−0.43–0.10) | 0.22 |

| Current partner | −0.03 (−0.38–0.33) | 0.89 | −0.51 (−0.92–−0.11) | 0.01 |

| Total live births | 0.03 (−0.06–0.13) | 0.47 | 0.02 (−0.09–0.12) | 0.78 |

| Hysterectomy | −0.09 (−0.30–0.11) | 0.38 | −0.36 (−0.70–−0.02) | 0.04 |

| Oophorectomy (bilat) | −0.03 (−0.34–0.29) | 0.87 | 0.32 (−0.11–0.76) | 0.14 |

| Postmenopausal | 0.35 (0.07–0.63) | 0.01 | 0.42 (0.13–0.71) | <0.01 |

| Poor or fair self-reported health | 0.25 (−0.06–0.55) | 0.11 | −0.13 (−0.48–0.22) | 0.46 |

| Beck Depression Inventory score (/10 increase) | 0.26 (0.02–0.51) | 0.04 | 0.23 (0.03–0.43) | 0.03 |

| Current estrogen use | −0.11 (−0.38–0.16) | 0.41 | −0.44 (−0.75–−0.13) | 0.01 |

| Current SSRI use | −0.17 (−0.48–0.14) | 0.27 | 0.41 (0.12–0.71) | 0.01 |

| Clinically severe incontinence | 0.01 (−0.02–0.05) | 0.45 | 0.02 (−0.03–0.08) | 0.46 |

| Stress predominant incontinence | −0.01 (−0.24–0.23) | 0.98 | −0.03 (−0.28–0.23) | 0.84 |

| BMI (/5 kg/m2 increase) | 0.03 (−0.05–0.12) | 0.42 | −0.07 (−0.17–0.03) | 0.17 |

Coefficients are adjusted for all predictors as well as clinical site and account for clustering within intervention group. Positive coefficients indicate worse functioning (ie more urine leakage, more sexual problems).

As reported elsewhere women randomized to the intervention group showed a mean weight loss of 7.8 kg during 6 months, representing 8% of baseline body weight, compared to only 1.5 kg (1.6%) in the control group (p <0.01 for difference between groups).13 The intervention was also associated with a 19% greater decrease in the number of incontinence episodes weekly after 6 months compared to controls (p = 0.01).

While there was a trend toward greater improvement in frequency of sexual activity during 6 months among participants randomized to the intervention vs control group, this difference did not reach statistical significance (table 5). Furthermore, the study intervention was not associated with improvements in overall sexual satisfaction, level of desire, urine leakage during sex or other sexual difficulties at 6 months (p >0.20 for all). These findings did not significantly change when we adjusted for variables such as Beck Depression Inventory score which differed by treatment group at baseline, or when we restricted our analysis to women who were sexually active or who reported significant dysfunction at baseline. Finally, we found no association between improvement in incontinence frequency, BMI or body weight during 6 months and improvement in sexual function in longitudinal models adjusting for treatment assignment (p >0.10 for all).

Table 5.

The effect of the intensive weight loss intervention on sexual activity and sexual functioning

| OR (95% CI)* | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual function domains assessed in all randomized participants:* |

||

| Frequency of sexual activity | 1.34 (0.99–1.81) | 0.06 |

| Overall sexual satisfaction | 1.28 (0.83–1.99) | 0.26 |

| Level of sexual desire | 1.12 (0.79–1.61) | 0.52 |

| Sexual problems scales assessed in sexually active participants:† |

||

| Urine leakage during sex | −0.09 (−0.27–0.10) | 0.37 |

| Difficulty with sexual activity | 0.03 (−0.11–0.16) | 0.68 |

Odds ratios are adjusted for clinical site and account for clustering within intervention groups. Odds ratios greater than 1.0 indicate better functioning associated with the intensive intervention.

Coefficients are adjusted for clinical site and account for clustering within intervention groups. Values are B (95% CI). Negative coefficients indicate fewer problems associated with the intensive intervention.

DISCUSSION

This study of sexual functioning in overweight and obese women with urinary incontinence provides new insight into the role of incontinence and obesity in female sexual dysfunction. A substantial proportion of women in our study reported dissatisfaction with sexual activity, low sexual desire or other sexual problems at baseline. Nevertheless, neither greater severity of incontinence nor higher BMI was significantly associated with sexual dysfunction among participants after adjustment for other factors. Furthermore, although women randomized to the weight loss intervention showed significant decreases in weight and incontinence relative to controls at 6 months, they did not demonstrate significant improvement in sexual function at 6 months based on a variety of measures.

Previous researchers noting the high prevalence of sexual problems in women with urinary incontinence recommended that clinicians assess for sexual dysfunction when evaluating women who present with this problem.20 Our findings suggest that evaluation of sexual function in women with incontinence should not be confined solely to the impact of incontinence on sexual activity. Contextual and psychosocial factors such as the comorbid symptoms of depression, menopausal symptoms and relationship factors may have an even more important role in influencing sexual function in this population.

Several previous studies reported an association between obesity and sexual dysfunction in women, although they tended to be small10 or to focus on residents of inpatient obesity programs who may not be generalizable to the population at large.11,12 Obesity has the potential to promote sexual dysfunction through several mechanisms including exacerbation of medical problems that contribute to sexual dys-function, alteration in circulating hormone levels affecting women's sexual interest and response, and change in body image relating to self-perception of sexual attractiveness. Our results suggest that while weight loss may have important benefits in overweight and obese women, amelioration of co-morbid factors such as depressive or menopausal symptoms may be as or even more important in improving sexual function in this population.

Several important limitations of this research should be noted. The PRIDE trial was restricted to overweight and obese women with at least 10 episodes of incontinence weekly and, thus, did not sample the full range of BMI or incontinence severity in the general population. There may be threshold effects in the relationships of BMI and incontinence to sexual dysfunction such that further increases in weight or in incontinence severity are not associated with further increases in sexual dysfunction. Additionally, the effects of these conditions on sexual function in women may be synergistic such that our findings in overweight women with incontinence may not be generalizable to women who have either problem alone.

We also do not currently have data on the sensitivity and reliability of the entire sexual functioning questionnaire used in the PRIDE trial. Although questionnaire items were adapted from previously validated instruments such as the Female Sexual Function Index and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Uri-nary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, additional research using other sensitive instruments may help confirm our findings. Finally, our assessment of sexual problems was necessarily limited to those women who reported at least some sexual activity during the 3 months before each clinical visit. If some women who were previously sexually active at baseline became inactive due to worsening of problems with arousal, lubrication, orgasm or pain, then it is possible that censoring these women at the 6-month visit may have introduced bias into our estimates of treatment effects.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that while a substantial proportion of overweight and obese women with urinary incontinence experience sexual dysfunction, the severity of this dysfunction may not be directly related to the severity of incontinence or obesity. Contextual and psychosocial factors such as the comorbid symptoms of depression, menopausal status and relationship factors may be stronger contributors to sexual dysfunction in this population. Additionally, we did not find that an intensive behavioral weight loss intervention improved sexual function relative to controls despite producing greater weight loss and decreased frequency of incontinence.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grants U01 DK067860, U01 DK067861 and U01 DK067862, and K24 DK068389 and K24 DK080775, from The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the Office of Research on Women's Health, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BMI

body mass index

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- PRIDE

Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

APPENDIX 1

Summary of sexual function measures

| Concept/Measure | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Overall sexual functioning - past 3 months | ||

| Frequency of sexual activity | 1–5 ordinal single item scale assessing frequency of sexual activity. Responses range from never to daily. Higher score indicates greater frequency. |

|

| Level of sexual desire | 1–5 ordinal single item scale assessing level of sexual desire or interest. Responses range from none to high/very high. Higher score indicates more sexual desire. |

Female Sexual Function Index |

| Overall sexual satisfaction | 1–5 ordinal single item scale assessing overall level of satisfaction. Responses range from very dissatisfied to very satisfied. Higher score indicates greater satisfaction. |

Female Sexual Function Index |

| Sexual problems - past 3 months (for sexually active women) | ||

| Leakage during sex scale | 3-item summated scale assessing the amount of urine leakage during sexual activity, the degree to which this leakage was bothersome, and the extent to which this leakage restricted sexual activity. Cronbach's alpha = 0.80. Score range is 1 to 5, with higher score indicating more problems. |

Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire |

| Difficulty with sexual activity scale | 4-item summated scale assessing difficulty with sexual arousal, problems with lubrication, difficulty achieving orgasm, and discomfort or pain during sexual intercourse. Cronbach's alpha = 0.67. Score range is 1 to 5, with higher score indicating more difficulty. |

Female Sexual Function Index |

APPENDIX 2 PRIDE investigators, staff, consultants, and Data and Safety Monitoring Board

The University of Alabama at Birmingham – Frank Franklin, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Holly E. Richter, PhD, MD (Co-Investigator); Kathryn L. Burgio, PhD (Co-Investigator); Leslie Abdo, BSN, RN, CCRC; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Kathy Carter, RN, BSN; Juan Dunlap; Stacey Gilbert, MPH; Sara Hannum; Anne Hubbell, MS, RD, LD; Karen Marshall; Lisa Pair, CRNP; Penny Pierce, RN, BSN; Clara Smith, MS, RD; Sue Thompson, RN; Janet Turman; Audrey Wrenn, MAEd.

The Miriam Hospital - Rena Wing, PhD (Principal Investigator); Amy Gorin, PhD (Co-Investigator); Deborah Myers, MD (Co-Investigator); Tammy Monk, MS; Rheanna Ata; Megan Butryn, PhD; Pamela Coward, MEd, RD; Linda Gay, MS, RD, CDE; Jacki Hecht, MSN, RN; Anita Lepore-Ally, RN; Heather Niemeier, PhD; Yael Nillni; Angela Pinto, PhD; Deborah Ranslow-Robles, Phlebotomist/MedAsst; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Deborah Sepinwall, PhD; Margaret E. Hahn, MSN, RNP; Vivian W. Sung, MD, MPH; Victoria Winn; Nicole Zobel.

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences – Delia West, PhD (Investigator).

The University of Pennsylvania – Gary Foster, PhD (Consultant).

The University of California, San Francisco (Coordinating Center) – Deborah Grady, MD, MPH (Principal Investigator); Leslee Subak, MD (Co-PI); Judith Macer; Ann Chang; Jennifer Creasman, MSPH; Judy Quan, PhD; Eric Vittinghoff, PhD; Jennifer Yang.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board:

The University of Utah Health Sciences Center – Ingrid Nygaard, MD (Chairperson).

The Children's Hospital Boston – Leslie Kalish, ScD.

The University of California, San Diego – Charles Nager, MD.

The Medical University of South Carolina – Patrick M. O'Neil, PhD.

The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine – Cynthia S. Rand, PhD.

The University of Virginia Health Systems – William D. Steers, MD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Melville JL, Katon W, Delaney K, Newton K. Urinary incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:537. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urwitz-Lane R, Ozel B. Sexual function in women with urodynamic stress incontinence, detrusor overactivity, and mixed urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1758. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tannenbaum C, Corcos J, Assalian P. The relationship between sexual activity and urinary incontinence in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handa VL, Harvey L, Cundiff GW, Siddique SA, Kjerulff KH. Sexual function among women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:751. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers RG, Kammerer-Doak D, Darrow A, Murray K, Qualls C, Olsen A, et al. Does sexual function change after surgery for stress urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse? A multi-center prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber MD, Visco AG, Wyman JF, Fantl JA, Bump RC. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:281. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauls RN, Silva WA, Rooney CM, Siddighi S, Kleeman SD, Dryfhout V, et al. Sexual function after vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:622. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of over-weight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend MK, Danforth KN, Rosner B, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein Body mass index, weight gain, and incident urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:346. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270121.15510.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito K, Ciotola M, Giugliano F, Bisogni C, Schisano B, Autorino R, et al. Association of body weight with sexual function in women. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:353. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melin I, Falconer C, Rossner S, Altman D. Sexual function in obese women: impact of lower urinary tract dysfunction. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1312. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolotkin RL, Binks M, Crosby RD, Ostbye T, Gress RE, Adams TD. Obesity and sexual quality of life. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:472. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subak LL, Wing R, Smith West DS, Franklin F, Vittinghoff E, Creasman JM, et al. Weight loss to treat urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandvik H, Seim A, Vanvik A, Hunskaar S. A severity index for epidemiological surveys of female urinary incontinence: comparison with 48-hour pad-weighing tests. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:137. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:2<137::aid-nau4>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers RG, Kammerer-Doak D, Villarreal A, Coates K, Qualls C. A new instrument to measure sexual function in women with urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:552. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures Models. Springer; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salonia A, Zanni G, Nappi RE, Briganti A, Deho F, Fabbri F, et al. Sexual dysfunction is common in women with lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary incontinence: results of a cross-sectional study. Eur Urol. 2004;45:642. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]