Abstract

Much recent effort has focused on identifying and characterizing cellular markers that distinguish tumor propagating cells (TPCs) from more differentiated progeny. We report here an unusual promoter DNA methylation pattern for one such marker, the cell surface antigen CD133 (Prominin 1). This protein has been extensively used to enrich putative cancer propagating stem-like cell populations in epithelial tumors, and especially, glioblastomas. We find that, within individual cell lines of cultured colon cancers and glioblastomas, the promoter CpG island of CD133 is DNA methylated, primarily, in cells with absent or low expression of the marker protein whereas lack of such methylation is evident in purely CD133+ cells. Differential histone modification marks of active versus repressed genes accompany these DNA methylation changes. This heterogeneous CpG island DNA methylation status in the tumors is unusual in that other DNA hypermethylated genes tested in such cultures preserve their methylation patterns between separated CD133+ and CD133− cell populations. Furthermore, the CD133 DNA methylation seems to constitute an abnormal promoter signature since it is not found in normal brain and colon but only in cultured and primary tumors. Thus, the DNA methylation is imposed on the transition between the active versus repressed transcription state for CD133 only in tumors. Our findings provide additional insight for the dynamics of aberrant DNA methylation associated with aberrant gene silencing in human tumors.

Keywords: CD133, DNA methylation, tumor propagating cells (TPC), histone modifications, cancer

Introduction

The existence of small pools of undifferentiated stem and early progenitor cells within discrete organ sites has been linked to functional aspects of normal tissue development, maintenance, and regeneration. Additionally, markers for such cells have been utilized to identify cell populations in cancers that may function as a source of cells giving rise to tumor propagating cells (TPCs) (1–3). A direct role for involvement of TPCs in neoplasia has required the use of the markers to isolate purified candidate cell populations to allow experimental validation of their tumorigenic properties (4–16). Much pioneering work of this type was performed in the hematopoietic system (4), and subsequently, many studies have relied heavily on the use of cell surface marker antigens to separate cellular fractions highly enriched for TPCs in solid tumors such as glioblastomas (9), breast (5), prostate (7), hepatocellular carcinomas (14, 15), colon (10–12), pancreatic (16), and head and neck cancers(13).

In adult and pediatric brain tumors, cells harboring the surface membrane protein CD133 (AC133; human prominin-1), which is normally expressed in a subset of putative neural stem/precursor cells in the normal adult central nervous system, have been identified (9, 17–19). CD133 belongs to a family of cell surface glycoproteins harboring 5 transmembrane domains (20) and was initially isolated during a gene screen to identify novel antigens expressed in hematopoetic stem cells (21, 22). CD133 marked cells in brain tumors have a capacity for unlimited self-renewal, as well as the ability, in small numbers, to initiate tumor formation and progression in xenograft model systems (9) thus satisfying key criteria required for classification of TPC’s. With similar approaches, CD133 has recently been designated as a marker associated with TPC’s in colon cancer (10, 11), although there is controversy as to whether this is the ultimate such cell population, as compared to cells marked by the surface antigen CD44, in this cancer (12). Moreover, more recent data indicate that, in normal mouse intestine, CD133+ cells are later precursor cells than the ultimate adult stem cell for this tissue (23).

In this report, we identify that abnormal, cancer specific, DNA hypermethylation in a CpG island in the immediate promoter area of CD133 occurs frequently in colon cancers and glioblastomas. This signature for epigenetically mediated transcriptional gene loss of function in cancer (24, 25) is unusual in its distribution for this gene. Interestingly, relating to a situation not heavily explored for other DNA hypermethylated genes, the CD133 promoter DNA methylation is heterogeneous between cell populations within individual tumors that this protein putatively marks as having more versus less TPC properties. The possible dynamics of aberrant DNA methylation for this cancer gene, as compared to most other genes for which this change has been described, are, thus, explored and discussed. Biological implications of modulating CD133 expression, with respect to mechanisms of gene repression, are explored through manipulating the DNA methylation status of the promoter.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

Colorectal and glioblastoma cell lines (HCT116, SW480, RKO, HT29, Caco-2, Lovo, COLO 320, COLO 205, DLD1, SW48, SW620, T98G, and U87 MG) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in appropriate medium and under conditions described by ATCC, with media obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DKO cells (HCT116 cells with genetic disruption of DNMT1 and DNMT3b) were cultured as previously described (26), as were the HSR-GBM1 (previously known as line 0913 by Vescovi and colleagues) glioblastoma-derived neurosphere cells (27). The Duke University cell lines (GBM; D566 MG, D263 MG, and D54 MG) were a kind gift of Dr. Gregory Riggins at The Johns Hopkins Oncology Center. For demethylation studies, cultured cells were treated with 1 μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (DAC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 72h with media changed every 24 hours. Trichostatin A (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was obtained from Sigma and used to treat cells at concentration of 300nM for 18h. Mock drug treatments were performed in parallel with drug free PBS.

Flow cytometric analysis and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)

Antibodies used in this study include CD133/1(AC133)-PE, CD133/1(AC133)-APC, CD133/2 (293C3)-PE (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), mouse IgG1-APC and mouse IgG1-PE (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). Cells were stained according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on BD FACSCalibur multicolor flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Dead cells were gated out by using 7-AAD (BD pharmingen, San Jose, CA) staining. Scatter plots were used to exclude cell aggregates. At least 10,000 events were acquired for each analysis. Cells expressing levels of CD133 higher than those seen in IgG controls were considered positive. All data were analyzed by BD CellQuest™ Pro v. 5.2 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cell sorting was performed on BD FACSVantage™ Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells with upper 15% or lower 15% fluorescent intensity of CD133 were collected for experiments.

Primer design

For expression studies using RT-PCR we designed primers using the open access program Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi) (28). Primer sequences for MSP analysis were designed using MSPPrimer (http://www.mspprimer.org) and their location in the CD133 promoter is indicated in Fig. 1C. All primer sequences are listed on Supplementary Table 1.

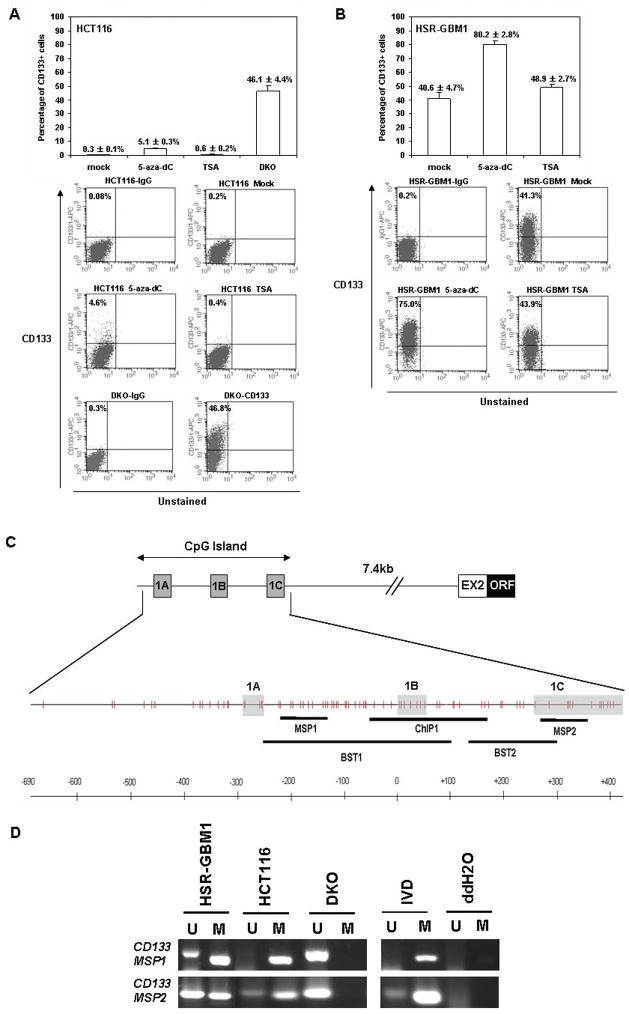

Figure 1.

CD133 expressing cells are increased in colorectal cancer and glioblastoma cells upon pharmacological or genetic disruption of DNA methyltransferases. (A) Upper panel, quantification of flow cytometric analysis of CD133 expression profiles in colorectal cancer cell line HCT116 after either mock, 5-aza-dC (5 μM, 72hrs) or TSA (300nm, 18hrs) treatment, and for DNA methyltransferase 1 and 3b knockout HCT116 cells (DKO, for double knockouts). Data were averaged from at least 3 independent experiments. Standard error bars are shown. Lower panel, one representative flow cytometric dot plot for each treatment is shown. The fluorescence of CD133 is depicted on the y axis, and the percentage of CD133+ cells (relative to the corresponding isotype control) is shown on the left upper corner of each plot. The bottom 2 plots represent the double knockout HCT116 cells stained with either IgG1 or CD133 antibody. (B) Upper panel, quantitation of flow cytometric analysis of CD133 expression profiles in glioblastoma, using the Vescovi line, HSR-GBM1, after either mock, 5-aza-dC (1 μM, 96hrs) or TSA (300nM, 18hrs) treatment. Data were averaged from 3 independent experiments. Lower panel, one representative flow cytometric dot plot of each treatment was shown. 5-aza-dC: 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine; TSA: Trichostain A. (C) Top line - Genomic structure of the promoter region of human CD133. The position of the CD133 promoter CpG island is shown and the alternative first exons are depicted (boxes marked 1a, 1b, and 1c) and their position and distance from the exon 2 (EX2) and remainder of the open reading frame (ORF) of the gene is shown. The second line depicts a schematic of the CpG’s in the island (vertical tic marks) and the, position of the DNA methylation assay with MSP primers is shown. The genomic structure shown is modified from (61) (D) MSP analysis of the promoter CpG islands of CD133 with two different primer sets (MSP1 and MSP2) in HCT116, DKO, and HSR-GBM1 cell lines. PCR products recognizing unmethylated (U) and methylated (M) CpG sites are analyzed on 2% agarose gels visualized with GelStar Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Cambrex Bio Science, Charles City, IA). IVD = in-vitro methyated control and ddH2O = water control containing no DNA.

Gene expression and methylation analyses

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), treated with DNase (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) protocol, and 1 μg total RNA subjected to the Superscript II first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For MSP analysis, DNA was extracted following a standard phenol-chloroform extraction method. Bisulfite modification of genomic DNA was carried out using the EZ DNA methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). We performed methylation analysis of the CD133 promoter using MSP primer pairs covering the putative transcriptional start site in the 5′ CpG island (29) with 1 μl of bisulfite-treated DNA as template and JumpStart Red Taq DNA Polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for amplification as previously described (30).

Primary colorectal and GBM tumor samples

All primary tumor samples used for this study were derived from formalin fixed and paraffin embedded surgical tissue samples obtained from the archive of the Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University Hospital with approval from the Institutional Review Board. This study compiles data for primary colorectal cancers of tumor stages I–III (n = 16) and normal colon controls (n= 19). GBM primary tumor genomic DNA from cancer (n=15) and non-cancer specimens (n=5) were obtained from the neuropathology archives after obtaining approval from the institutional review board of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Five non-cancer brain tissues used in this study were also obtained from the Brain Tumor Stem Cell Laboratory at Johns Hopkins with institutional review board approval. Genomic DNA was prepared using standard phenol/chloroform extraction methods.

Western Blotting analysis of CD133 protein

Xenograft tumor tissues were prepared as described previously (31). Lysates were cleared of insoluble material by centrifugation. Samples were boiled in SDS sample buffer, equal amounts of protein were loaded and electrophoresed through SDS-PAGE gels, and resolved proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk dissolved in TBS containing 0.02% Tween 20, and then incubated with primary antibody diluted in the same buffer. We used antibody against CD133 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at 1 μg/ml and 1:5000 dilution, respectively, for immunoblot analysis. Blots were developed with Super Signal Chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (32, 33). For each immunoprecipitation, 4 μg of either anti-dimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys4), anti-trimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys 27) or Rabbit IgG (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA), or 2 μg of anti-histone H3 antibody (Abcam Cambridge, MA) was used in a total volume of 4mL. Immunoprecipitated DNA was collected using magnetic Dynabeads protein A and Dynabeads protein G (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After reverse-crosslinking, DNA was treated with 0.2 μg/μL RNase A (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ), 0.2 μg/μL Proteinase K (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), recovered using QIAquick PCR purification kit columns and solutions (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), and was eluted in a final volume of 100 μL. Immunoprecipitated DNA was then quantified by real-time PCR using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Primers were designed for 3 different regions of the CD133 promoter (Fig. 5B). All primer sequences are listed on Supplementary Table 1. The enrichment of each histone mark was analyzed after normalization of the bound DNA for each mark to the amount of DNA associated to histone H3 at the same region of the promoter.

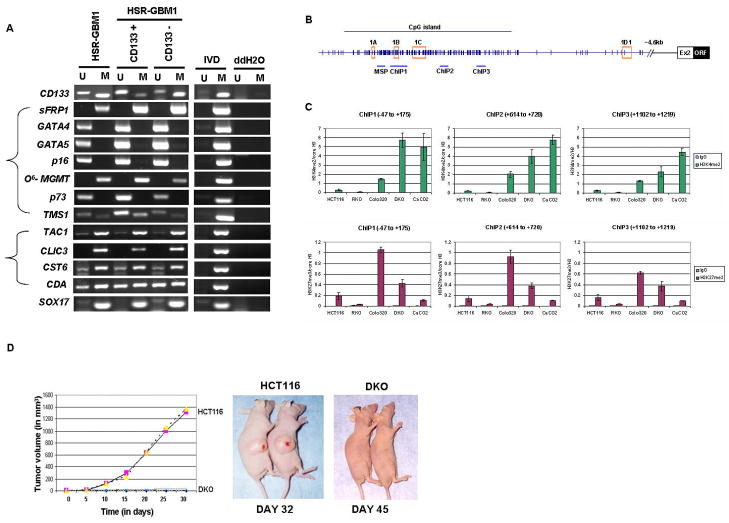

Figure 5.

(A) MSP analysis of CD133 gene and other genes in unsorted neurosphere cells (HSR-GBM1) and CD133 positive/negative cells from neurosphere cells (HSR-GBM1). ‘M’ and ‘U’ bands indicate methylated and unmethylated signals, respectively. IVD = in vitro methylated DNA, ddH2O=water control adding no DNA. (B–C) Relationships between DNA methylation states of CD133 and histone modifications in colorectal cancer cells. (B). Chromatin IP with rabbit IgG(control), anti-histone H3, anti-dimethyl H3K4 (active mark), and anti-trimethyl H3K27 (repressive mark) was performed on wild type HCT116, RKO, Colo320, DKO and Caco-2 cells. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by realtime-PCR using primers designed for 3 different regions around 1B transcription start site within the CpG island in the CD133 promoter (−47 to +175, +614 to +720, +1102 to +1219). (C) Upper panel, real-time PCR analysis of dimethyl H3K4 enrichment over histone H3 at each region is shown sequentially from left to right with the most upstream region on the left. Lower panel, real-time PCR analysis of trimethyl H3K27 enrichment over histone H3 at each region. The values were averaged from at least 2 independent ChIP experiments and multiple real-time PCRs. Standard error bars are shown. (D) Loss of tumorigenicity for CD133 expressing CRC cells. Wild type HCT116 and isogenic DKO cells lacking DNMT1 and DNMT3b and highly enriched in CD133 positive cells were tested in vivo, in SCID mice, for tumor growth. Right panel, Duplicate experiments with 6 animals in each group were performed and tumor volume plotted against time for HCT116 (pink square and yellow triangle) or DKO (blue X or purple open circle). Typical tumor growth in animals is shown in Left panel.

Tumorigenicity Assay

Cells were harvested before inoculation and resuspended in serum-free medium at a concentration of 5 × 107 cells per milliliter. Cells (5 × 106 cells, 0.1 ml) were then inoculated subcutaneously at the proximal dorsal midline into 3- to 4-week-old female athymic nu/nu mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). Tumor sizes in two dimensions were measured twice weekly, and volumes were calculated using the formula (L × W 2) × 0.5, where L is length and W is width, as previously described (34). Mice were housed in barrier environments, with food and water provided ad libitum.

Results

CD133 positive cell numbers are enhanced by treatment with demethylating agents or genetic deletion of DNA methyltransferases

Although, best characterized for identifying normal brain stem cells (35, 36) and TPCs in brain tumors (9), CD133 has also been utilized as a marker for colon cancer TPCs (10, 11). It is in this latter context, that we first noted an unusual relationship between promoter DNA methylation and CD133 expression. In characterizing CD133 cells as a marker for TPC’s in the colon cancer cell line, HCT116, and a derivative of this line in which two DNA methyltransferases, DNMT1 and DNMT3b have been genetically disrupted, the double knockout or DKO cells, we found, as expected, low levels (0.3±0.1%; upper panel Fig. 1A) of CD133+ cells in the parent line, but markedly increased levels of such cells in the DKO line (46.1±4.4%; upper panel Fig. 1A). These latter cells have lost nearly all genomic 5-methylcytosine and hundreds of DNA hypermethylated and silenced genes become demethylated and re-expressed (26, 37). To further test why the DKO cells express high levels of CD133, we subjected the parent line, HCT116 to pharmacologic induction of DNA demethylation with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (DAC). We compared the effects of DAC treatment to treatment of the cells with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA), which is known not to induce re-expression of genes harboring densely DNA hypermethylated promoter CpG islands (38). We observed an increase of a CD133+ sub-population of cells in DAC-treated HCT116 cells (5.1±0.3%) compared with mock treated (0.3±0.1%) or TSA treated (0.6±0.2%) cells as shown in Figure 1A.

To test, preliminarily, whether CD133 hypermethylation also occurs in brain tumors, in which CD133 has been shown as a putative marker for TPCs as well, we applied similar pharmacological induction of DNA demethylation to cultured human glioblastoma (GBM) neurospheres (HSR-GBM1), originally isolated directly from glioblastoma patient samples by Vescovi and colleagues and enriched for CD133+ tumor cells (27). Consistently, we observed significant increases of a CD133+ sub-population of cells in DAC-treated HSR-GBM1 cells (80.2±2.8%) compared with mock treated (40.6±4.7%) or TSA treated (48.9±2.7%) cells as shown in Figure 1B. Taken together, our results obtained in two independent systems using both CRC and GBM cell lines with either genetic or pharmacological demethylated genomes indicated significant increases in CD133+ cells, thereby suggesting a role for promoter methylation in the regulation of CD133 levels.

Expression and DNA methylation of CD133 gene in human colorectal cancer and glioblastoma cell lines

Despite the potential importance of CD133 in stem cell biology, little is known about the transcriptional regulation of CD133 expression. One recent report analyzing the human CD133 gene 5′UTR region identified at least 7 alternatively spliced isoforms and 3 putative promoters within a CpG-island located between upstream alternative 5′ UTR and Exon2 (29) (Fig. 1C). To query these sequences for methylation, we first designed primers in two different regions, MSP1 primers for an upstream promoter region ahead of alternate exon 1B, and MSP 2 primers for a more downstream promoter area around exon 1C, for methylation specific PCR (MSP) assays of the HCT116, DKO, and HSR-GBM1 cell lines. We found complete methylation of the promoter region CpG islands in HCT116 cells, partial methylation in the HSR-GBM1 cell line with somewhat more in the MSP1 region,, and no detectable methylation in the DKO cells (Fig. 1D). This result correlated precisely with the levels of CD133 protein levels in the cell lines as assayed by flow cytometric analysis confirming that cell surface CD133 levels in these cultured tumor cells directly correlated with promoter DNA hypermethylation. Importantly, we confirmed the MSP results for methylation with bisulfite sequencing of the two primer regions (primers BST1 and BST 2 –Fig. 1C) with excellent agreement. Thus, there is, in the sequencing, virtually complete methylation of the entire CpG island in HCT116 cells, more methylation in the MSP1 than the MSP 2 region in HSR-GBM1 cells, and lack of methylation in the DKO cells (Supplemental Fig. S1)

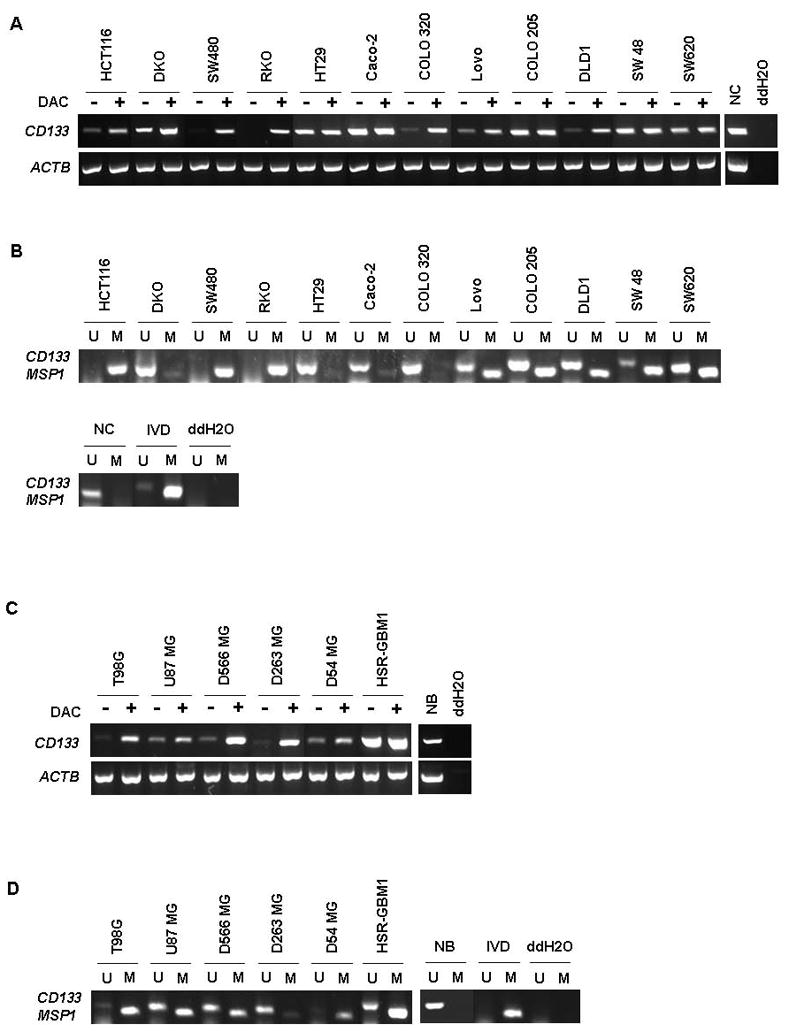

Having confirmed our MSP primers, and their monitoring of methylation density to protein expression, we next expanded our study to include a panel of CRC and GBM cell lines and compared the DNA methylation status of CD133 with expression of the gene as examined by sensitive RT-PCR analysis before and after DAC treatment. The primers for this assay monitor exon 5 which is common to all transcripts reported for CD133 in brain and colon (29). Importantly, we first found that we could detect CD133 expression in normal colon (Fig. 2A) as would be expected given its defined presence in a subset of expanding cells above the intestinal crypts (23). In addition to HCT116, we detected little or no CD133 expression in 4 CRC lines, SW480, RKO, COLO 320, and DLD1, and all of these lines showed increased expression of CD133 following DAC treatment (Fig. 2A). Complete or partial methylation of the gene was found, using the upstream MSP1 primer set (Fig. 2B), in 3 of these cell lines, HCT116, SW480 and RKO, and partial methylation in a fourth (DLD1) indicating good correlation between low expression and presence of promoter DNA methylation in 4 out of 5 cell lines, with the exception being COLO 320. Interestingly, DAC also increases the expression of the gene in this latter cell line indicating the drug can activate the gene through influences on chromatin other than those associated with DNA de-methylation, or that upstream factors have been activated by the drug which up-regulate expression of the gene. In contrast to the above cell lines, significant basal expression of CD133 was found in 6 CRC lines (HT29, Caco-2, LoVo, COLO 205, SW48, and SW620) and this expression was not changed by DAC treatment (Fig. 2A). Two of these cell lines (HT29 and Caco-2) were completely unmethylated for CD133, while there was partial methylation in the other 4 cell lines (LoVo, COLO 205, SW48, and SW620) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Expression analysis and methylation analysis of CD133 gene in colon cancer and glioblastoma(GBM) cell lines. (A, C) CD133 expression levels were examined in (A) twelve colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT116, DKO, SW480, RKO, HT29, Caco-2, COLO 320, Lovo, COLO 205, DLD1, SW48, and SW620) and normal colon (NC) and (C) 6 GBM cell lines (T98G, U87 MG, D566 MG, D263 MG, D54 MG, and HSR-GBM1) and normal brain (NB). Lanes marked + are with and those −, without treatment with DAC (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine). The gene Actin B serves as a positive control for RNA quality and loading in both A and C. ddH2O=water control adding no cDNA. (B, D) MSP analysis of the DNA methylation status of the 5′ CpG island in the CD133 gene in a panel of (B) colon cancer and (D) Glioblastoma (GBM) cell lines. M=methylation signal; U=unmethylated signal. IVD= in vitro methylated DNA. NC and NB indicate normal colon tissue and normal brain tissue, respectively. ddH2O=water control adding no DNA.

In the panel of GBM cell lines, low level expression of CD133 transcripts was found in 5 out of the 6 examined including T98G, U87 MG, D566 MG, D263 MG, D54 MG, and HSR-GBM1. HSR-GBM1, the neurosphere cell line, which is enriched for CD133+ cells, had high basal expression (Fig. 2C) with partial methylation (Fig. 2D). Also, as we observed in colon, high level CD133 expression was detected in normal brain (39), and after DAC treatment, 3 cell lines displayed significantly increased levels of CD133 transcripts (T98G, D566 MG, and D263 MG), while 2 showed more modest increases (U87 MG and D54 MG). The T98G and D54 MG cell lines showed lack of gene expression correlated with complete methylation by the MSP reaction. U87 MG and D566 MG cell lines showed amplification products in both methylated and unmethylated MSP reactions, consistent with partial methylation (Fig. 2D).

We also have examined the above CRC and GBM cell lines, using our more downstream set of MSP primers (MSP2), (Supplementary Fig. S3 A and B). The methylation pattern of MSP2 in colon cancer cell lines showed a similar pattern to the MSP1 primer set in Fig. 2B. However, in the GBM cell lines, including those fully methylated as studied with the MSP 1 primers above (T98G and D54), the MSP2 primers detected partial and less methylation as compared to the results with the MSP1 primers (compare Fig. 2D with Fig. S3B). Taken together, this data suggests that the region upstream of alternate exon 1B, examined by the MSP1 primer set generally correlates best with the expression of CD133.

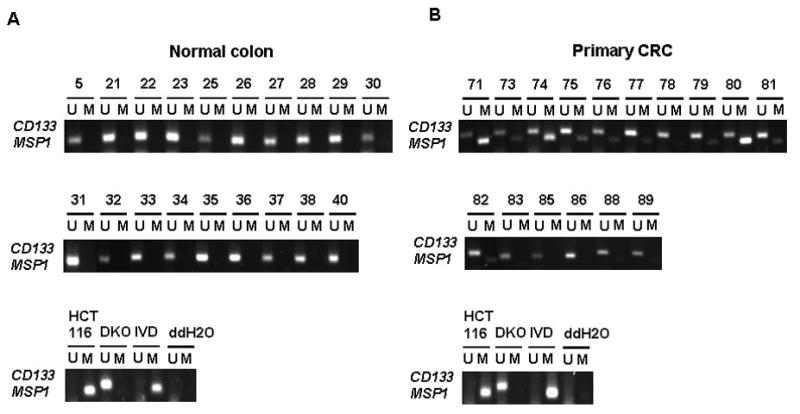

Methylation of the human CD133 gene promoter in primary CRC tumors and GBM tumor samples

Having confirmed a high frequency of hypermethylation in the CD133 promoter in CRC and GBM cell lines, we investigated the methylation status of the gene in primary, non-cultured, tumor samples. We first established, using the MSP1 primers, that CD133 promoter methylation was absent in normal colon and brain using samples from non-cancer patient tissue (Fig. 3A, 4A). This indicates that CD133 methylation may constitute an abnormal finding in tumor cells. Indeed, we discovered that a surprisingly high frequency (10/16 – 62%) of the primary CRC samples analyzed had some degree of CD133 gene methylation (Fig. 3B). In the GBM primary tumors, we observed similar results with 93% (14/15) having some degree of CD133 gene methylation (Fig. 4B). Using the MSP2 primers, we, again, detected no methylation in normal colon and brain (Supplementary Fig. S4A and S5A), but methylation was seen in primary CRC and GBM samples at a lower frequency than we demonstrated with MSP1 in Fig. 3B and 4B (Supplementary Fig. S4B and S5B). These data were similar to the analyses in CRC and GBM cell lines. Taken together, our data suggest that CD133 hypermethylation arises sometime during the progression of primary CRC and GBM and is not a normal regulatory event for the gene during cell renewal processes.

Figure 3.

Methylation analysis of CD133 gene in primary CRC tissues versus normal colon tissues. (A) normal colon tissues (B) primary CRC tissues. M=methylation signal; U=unmethylated signal. IVD= in vitro methylated DNA. ddH2O=water control adding no DNA. Numbers represent normal colon (5, 21–23, 25–38, 40) and primary CRC samples (71, 73–83, 85–86, 88–89).

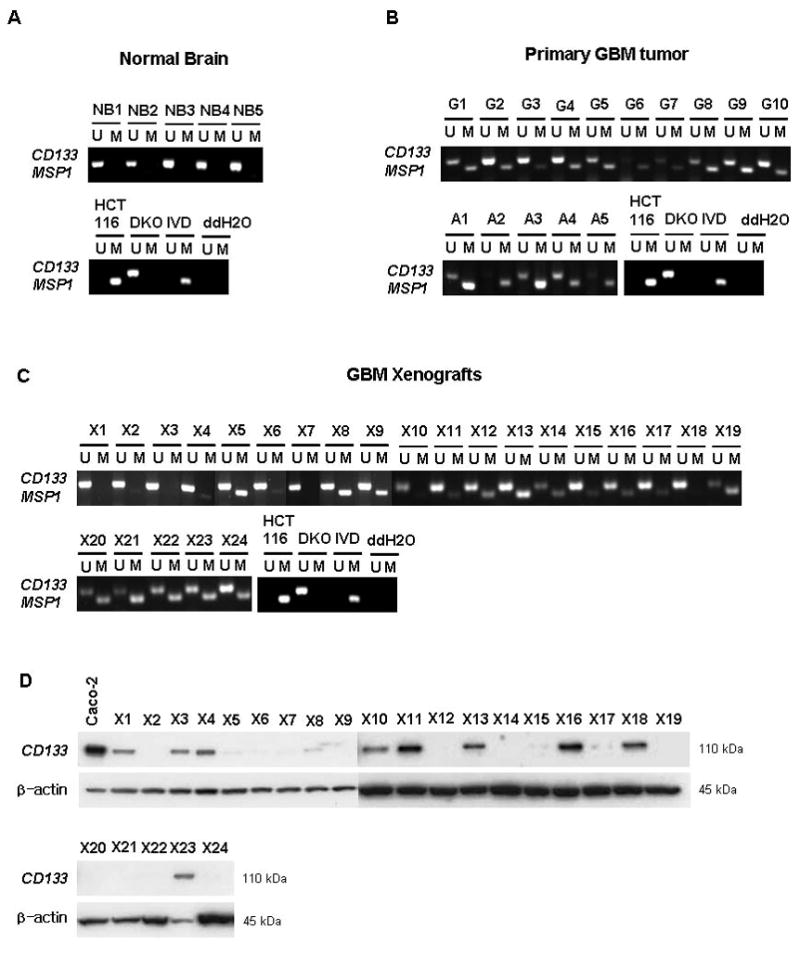

Figure 4.

(A–C) Methylation analysis of CD133 gene in primary brain and GBM tissues. (A) normal brain tissues (B) primary GBM tumor tissues (C) xenograft samples from GBM tissues. (D) Western-blot analysis of CD133 protein in xenograft samples. M=methylation signal; U=unmethylated signal. IVD= in vitro methylated DNA. ddH2O=water control adding no DNA. Numbers represent normal brain samples (NB1–5), primary GBM tumor samples (G1–10; grade IV, A1–5; grade III; anaplastic astrocytoma), xenograft samples (X1–X24). Caco-2 cells were used as a positive control for CD133 expression. β-actin is also shown as a control for protein loading for western blotting.

To further study relationships between the abnormal CD133 promoter methylation and expression of the gene in tumors, we examined a panel of serially passaged GBM xenografts. These xenografts have been extensively characterized for molecular characteristics that can be investigated to understand the basis of variation in GBM response to specific therapies (31, 40), and would be expected to be enriched for TPCs as measured by their recapitulation of molecular alterations, such as EGFR amplification, found in human GBM tumor samples (41). Here we examined a panel of these tissues for associations between CD133 protein expression level and methylation status. The results indicate a striking heterogeneity for CD133 methylation in these samples which does not strongly correlate with protein expression. The majority of samples show strong signals for unmethylated alleles as compared to the methylation signals for alleles of the CD133 gene (Fig. 4C). Since we are monitoring human and not mouse sequences in these samples, these unmethylated signals clearly emanate from tumor cells. Five (X12, X19, X20, X21, and X22) out of 12 (X5, X8, X9, X12, X14, X15, X17, X19, X20, X21, X22, and X24) samples which don’t have CD133 protein expression by western blot analysis (Fig. 4D) have prominent methylation signals, equal or greater than the unmethylated signal (Fig. 4C). However, there are xenografts with absent protein that have little or no methylation. Clearly, then, while there may be some relationship in tumors, for the steady state population dynamics between CD133 expression and the methylation status of the promoter, other mechanisms than DNA methylation may also help determine expression levels of CD133. Studies of chromatin composition of the CD133 promoter region, detailed later below, help expand our understanding of this expression control.

Occurrence of CD133 DNA hypermethylation in subpopulations of tumor cells and relationship to hypermethylation of other genes

Much experimental evidence suggests that CD133+ and CD133− cells isolated from human tumor GBM and CRC samples differ in their capacity to initiate and propagate tumors in animal xenograft model systems (9–11) with the CD133+ cells requiring small number of cells to initiate rapidly growing tumors. Although the dynamics underlying the appearance of CD133 DNA methylation, differentially between tumor cell populations, is not clear, we suspected that this pattern appeared to be an unusual event with respect to abnormal promoter DNA methylation in cancer. Generally, for many of the genes involved, one speculates that tight epigenetic silencing would favor tumor cell survival or growth of all populations. However, for CD133 from the marker roles predicted, it is expected that its expression would be dynamic being high in a minority of TPCs with higher tumorigenicity and lower in larger numbers of cells with lesser tumorigenic properties. We, thus, wondered whether other genes might also show similar differences in methylation patterns, perhaps indicating global hypermethylation differences between putative TPCs versus less tumorigenic cell populations in general. To test this, we utilized FACS to isolate highly purified CD133 positive and CD133 negative cell fractions (>90% pure for each expression state, Supplemental Fig. S2) from the HSR-GBM1 cell line neurospheres, and subjected these to MSP analysis. To verify the efficiency of separation, we first tested the methylation status of the CD133 promoter which as anticipated displayed strong methylation in the CD133 negative, but less in the positive fraction (Fig. 5A). We next examined in unsorted HSR-GBM1, and CD133 positive and negative cells sorted from this cell line, the methylation status of seven genes well known to be DNA hypermethylated with high frequency in multiple cancer types including p16, sFRP1, GATA4, GATA5, O6-MGMT, p73, and TMS1. We also examined four additional genes, TAC1, CLIC3, CST6, and CDA, all recently identified as DNA hypermethylated in GBM as identified in a genome-wide screen (42). We, finally, looked at Sox17, a gene known to regulate fetal hematopoietic stem cell (HSCs) function (43) and recently identified in our lab to be DNA hypermethylated in CRC with high frequency (44). None of the tested genes showed differential methylation patterns between the two different subsets of cells (Fig. 5A) being either fully methylated (sFRP1, TAC1, CLIC3, MGMT, and SOX17), partially methylated (CST6, CDA, and TMS1), or unmethylated (GATA4, GATA5, p16, and p73) in both CD133 + and − cell populations. These data then imply that CD133 DNA hypermethylation is unusual in the degree to which it differs in extent between tumor subpopulations of cells invoked to be more or less tumorigenic.

CD133 expression is associated with a balance between enrichment of dimethyl-H3K4 (H3K4me3) and H3K27me3

Because of the unusual dynamics, seen directly above, for CD133 promoter DNA methylation between tumor cell populations, we wondered how this might associate with chromatin changes we have previously associated with densely DNA methylated cancer genes (32, 45). In this regard, we have associated a balance between two histone marks, dimethyl-H3K4 (H3K4me2), a histone modification associated with active genes, and trimethyl-H3K27 (H3K27me3), a mark placed by the polycomb complex (PcG) in low expression genes (46). We have observed that the PcG mark is present at densely DNA methylated cancer genes and remains, and even increases, after DNA demethylation leads to a low re-expression state for the genes (45). However, the active H3K4me2 mark is far lower when the genes are DNA methylated than when they are demethylated and re-expressed (45). Essentially, these above relationships seemed to hold for CD133. We examined, by quantitative, real time PCR, ChIP assay, three different regions around the 1B transcription start site within the CpG island in the CD133 promoter and normalized the values to those for localization of total histone H3 to these regions (Fig. 5B), in HCT116, RKO, Colo320, DKO and Caco-2 cells. The H3K4me2 mark dominates over the PcG, H3K27me3 mark, which is, however, still present, at all regions of the promoter studied in the DKO and Caco-2 cells, where CD133 is completely DNA unmethylated and expressed (Fig. 5C). This pattern fully resembles the bivalent chromatin seen in a group of low expression genes in ES cells (47), and in our previous work (45), for other DNA hypermethylated genes when they are re-expressed in association with removal of DNA methylation. In contrast, in wild type HCT116 cells and RKO cells, where CD133 is fully DNA hypermethylated and silenced, little enrichment of H3K4me2 over histone H3 is observed at any of the promoter regions examined. CD133 promoter H3K27me3 enrichment is detected, but at low levels in these cell lines. Notably, in Colo320, where CD133 is silenced, but in the absence of DNA methylation, there is a very significant enrichment, as compared to all of the other cell types examined, of the repressive H3K27me3 mark at all regions studied, with striking dominance over the presence of the active H3K4me2 mark ( Fig. 5B). These above data, in summary, suggests that PcG may play its strongest role for CD133 silencing in the absence of DNA methylation – and that this PcG mark functions in a balance between DNA methylation and levels of the active mark, H3K4me2, to help determine the states of CD133 expression exhibited by the CRC lines studied.

Does induced DNA demethylation and re-expression of CD133 correlate with appearance of TPCs?

Although there is no known function of CD133 expression in TPC’s, one might question whether our unique ability to induce increasing populations of CD133 expressing cells, as we have with DAC treatment of cells, or in the DKO cells, would yield cells with increased tumorigenic potential. We thus tested this question for the DKO cells. In fact, even though this isogenic counterpart of the wild type, HCT116 CRC line has nearly 50% CD133 positive cells, these cells are unable to grow tumors in SCID mice (Fig. 5D). This could be evidence of lack of a true relationship for the CD133 mark in defining the most tumorigenic cells or, more likely, because of the effects of the profound overall DNA demethylation in DKO cells, including its associated re-expression of many known, and candidate, anti-tumor genes (37).

Discussion

Numerous markers have been used to isolate and characterize stem-cell like TPCs. For example, specific types of leukemia harbor cells with a CD34+/CD38− phenotype (6) which can induce cancer after serial transplantation. Breast and prostate cancer TPCs have been characterized by CD44+/CD24 low lin- (5) and CD44+/α2 β1hi/CD133+ (7), while TPCs in brain tumors, including medulloblastoma (17, 18) and, glioblastoma (9, 19) and, most recently, in colon carcinomas (10, 11) have been said to harbor the CD133+ marker.

While the CD133 marker stands as the principal one for TPC’s in brain, and a potential one in CRC, there is still controversy as to whether the populations of cells carrying this feature are the ultimate tumorigenic cells in these cancers. With regards to CD133, recent evidence (48) suggests that only a subset of primary GBM’s are maintained by CD133+ TPCs. Some GBM’s that lack CD133 expression can be driven and sustained by CD133− brain tumor stem cells with the abilities to self-renew, differentiate, and form tumors in nude mice. Results presented here, that show a lack of detectable CD133 expression in several serially-passaged GBM xenografts (Fig. 4D), are consistent with the concept of CD133− GBM cells that can self-renew and perform as TPC’s.

We have observed an unusual, consistent cell heterogeneity for abnormal CpG island promoter DNA methylation in the CD133 gene in two tumor types. In normal development and adult cell systems involving these cell systems, expression of this gene is thought to define normal stem/precursor cells in brain, and a small, more transient expansion precursor cell population in colon (23). Clearly then, expression of CD133 is normally down-regulated during normal lineage commitment and cell differentiation, but our data indicate that this expression shift is not associated with dense promoter methylation in these settings. Our very sensitive MSP assay would have most certainly picked up such a cell population since most cells in brain and colon would be expected to have the down-regulated expression discussed above. Thus, the CpG island methylation we observe in brain and colon cancers appears to constitute yet another example of an abnormal and cancer-specific imposition of the DNA modification on epigenetic gene regulation in neoplasia.

How, then, do we explain the heterogeneity of DNA methylation in terms of cell populations for CD133 within the cancers? Clearly, there is some relationship between the methylation and expression status of the gene since we see enrichment for the silent state and more DNA methylation when we separate cells in the GBM neurosphere lines, and we see up-regulation of expression that generally corresponds to drug-induced and genetically induced inhibition of DNMT’s. However, the steady state relationships between the DNA methylation and expression of the gene in both cell lines and primary tumors are less clear. This suggests a dynamic shifting in cell populations where down-regulation is not one-on-one correlated with the DNA methylation and is, at least initially, controlled by the same mechanisms that would occur in normal cell renewal and not involve DNA methylation. The DKO cells, where the DNA methylation has been completely erased, and which yet have a mixture of cells with and without CD133, illustrate this well.

We have also found that many genes which get abnormally DNA methylated in cancers have, in embryonic cells (33), and in adult cancers especially when DNA methylation is removed and the genes are re-expressed (45), a promoter chromatin pattern that others have termed as “bivalent” (47, 49). This is characterized by presence of the PcG mark H3K27me3, but balanced by simultaneous presence of the activating mark, H3K4me. Such chromatin, which is well seen (Fig. 5C) for CD133 in multiple CRC cell lines studied, including HCT 116 cells and their isogenic counterparts, the DKO cells, is thought, in ES cells, to hold genes in a state of low, “poised” transcription until they need to be activated, at which time there is a shift in the promoter chromatin towards the active H3K4me mark (47, 49). This dominance of the H3K4me mark is seen for CD133 in the Caco-2 cells (Fig. 5C), a cell line which has uniformly high expression of the gene.

For most tumor suppressor genes that become abnormally DNA hypermethylated in cancer, their expression would select against tumor cells, so they exist in a state of low expression, in early cell populations which enter tumor progression, and in their later progeny. Indeed, as we now show for a series of genes in our present study, abnormal promoter DNA methylation, and the heritable silencing patterns associated with it, appear to be set and maintained between CD133− and CD133+ cells isolated from a GBM neurosphere cell line and which have sharply differing status of CD133 methylation. Moreover, for many genes, we and others (50–55) have shown that abnormal promoter CpG island methylation arises early in tumor progression at pre-invasive stages. Thus, from the beginning of tumorigenesis, these genes are vulnerable for imposition of the DNA methylation, which facilitates abnormal retention of tight transcriptional silencing, and which is reflected in all of the tumor cell populations throughout the life history of the cancer.

To our knowledge, for the process of abnormal gene promoter DNA hypermethylation in cancer, the present observations for CD133 are unique in showing striking heterogeneity between isolated cell populations in a single tumor culture line. Certainly, heterogeneity such DNA methylation has been observed in total cell populations from cultured and primary cancers for genes other than CD133., However, this appears to be a more uniform heterogeneity involving cells throughout the tumor and manifesting as quantitative differences between alleles of a given gene (56). This latter type of abnormal promoter CpG island DNA methylation can even be quantitatively shifted by changes in environmental surrounding for the tumor cells, as we have shown for the E-cadherin gene in culture (57). Interestingly, others have reported hypermethylation of the CpG island located in the promoter region of the stem/precursor cell marker CD44, used to identify TPCs in breast and colon cancers, with concomitant gene silencing, in human prostate cancer (58), and neuroblastoma (59). However, whether this is a stable or dynamic mark is not known. It will then be of great interest to exploit the situation observed for CD133 as a model for how abnormal promoter DNA methylation patterns evolve during tumorigenesis.

Finally, our studies may be important for the consideration of using “epigenetic” therapy (60) to target reversal of abnormal gene silencing in cancer. It is, in this context, antithetical to think such treatments might be beneficial if, indeed, one result might be re-expression of a marker, such as CD133, that may define a TPC population of cells. However, in the context of re-expressing a battery of abnormally DNA methylated genes, hundreds of which appear to be present in a given primary tumor (37), this may not be a problem. In fact, as we show, DKO cells, in which widespread DNA demethylation has occurred in a setting where a large population of CD133+ cells has appeared, are no longer tumorigenic in NOD-SCID mice (Fig. 5D). This question opens up an area for important pre-clinical studies relative to CD133, CD44, and other TPC marking genes that might be DNA hypermethylated in human cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by ES011858 National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), CA116160 National Institute of Health (NIH). Other sources of funding for the xenografts are NS49720 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and P50CA097257, CA94971 National Institute of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–11. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer Stem Cells. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:1253–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalerba P, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:267–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.062105.204854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–8. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nature Medicine. 1997;3:730–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Prospective Identification of Tumorigenic Prostate Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65:10946–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsui W, Huff CA, Wang Q, et al. Characterization of clonogenic multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2004;103:2332–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–10. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park I-K, et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:10158–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prince ME, Sivanandan R, Kaczorowski A, et al. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:973–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suetsugu A, Nagaki M, Aoki H, Motohashi T, Kunisada T, Moriwaki H. Characterization of CD133+ hepatocellular carcinoma cells as cancer stem/progenitor cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;351:820–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin S, Li J, Hu C, Chen X, Yao M, Yan M, Jiang G, Ge C, Xie H, Wan D, Yang S, Zheng S, Gu J. CD133 positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells possess high capacity for tumorigenicity. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1444. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, et al. Identification of Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Research. 2007;67:1030–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, et al. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:15178–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a Cancer Stem Cell in Human Brain Tumors. Cancer Research. 2003;63:5821–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan X, Curtin J, Xiong Y, Liu G, Waschsmann-Hogiu S, Farkas DL, Black KL, Yu JS. Isolation of cancer stem cells from adult glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene. 2004;23:9392–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corbeil D, Fargeas CA, Huttner WB. Rat Prominin, Like Its Mouse and Human Orthologues, Is a Pentaspan Membrane Glycoprotein. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;285:939–44. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin AH, Miraglia S, Zanjani ED, et al. AC133, a Novel Marker for Human Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells. Blood. 1997;90:5002–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miraglia S, Godfrey W, Yin AH, et al. A Novel Five-Transmembrane Hematopoietic Stem Cell Antigen: Isolation, Characterization, and Molecular Cloning. Blood. 1997;90:5013–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The Epigenomics of Cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhee I, Bachman KE, Park BH, et al. DNMT1 and DNMT3b cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416:552–6. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, et al. Isolation and Characterization of Tumorigenic, Stem-like Neural Precursors from Human Glioblastoma. Cancer Research. 2004;64:7011–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandes JC, Carraway H, Herman JG. Optimal primer design using the novel primer design program: MSPprimer provides accurate methylation analysis of the ATM promoter. Oncogene. 2007;26:6229–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shmelkov SV, Jun L, St Clair R, et al. Alternative promoters regulate transcription of the gene that encodes stem cell surface protein AC133. Blood. 2004;103:2055–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkaria JN, Yang L, Grogan PT, et al. Identification of molecular characteristics correlated with glioblastoma sensitivity to EGFR kinase inhibition through use of an intracranial xenograft test panel. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2007;6:1167–74. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fahrner JA, Eguchi S, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Dependence of histone modifications and gene expression on DNA hypermethylation in cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7213–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohm JE, McGarvey KM, Yu X, et al. A stem cell-like chromatin pattern may predispose tumor suppressor genes to DNA hypermethylation and heritable silencing. Nat Genet. 2007;39:237–42. doi: 10.1038/ng1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park BH, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Genetic disruption of PPARdelta decreases the tumorigenicity of human colon cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:2598–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051630998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uchida N, Buck DW, He D, et al. Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:14720–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamaki S, Eckert K, He D, SR, Doshe M, Jain G, Tushinski R, Reitsma M, Harris B, Tsukamoto A, Gage F, Weissman I, Uchida N. Engraftment of sorted/expanded human central nervous system stem cells from fetal brain. J Neorosci Res. 2002;69:976–86. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuebel KE, Chen W, Cope L, Glöckner SC, Suzuki H, Yi JM, Chan TA, Neste LV, Criekinge WV, Bosch SV, van Engeland M, Ting AH, Jair K, Yu W, Toyota M, Imai K, Ahuja N, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Comparing the DNA Hypermethylome with Gene Mutations in Human Colorectal Cancer. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:1709–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron EE, Bachman KE, Myohanen S, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Synergy of demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition in the re-expression of genes silenced in cancer. Nat Genet. 1999;21:103–7. doi: 10.1038/5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbeil D, Roper K, Hellwig A, et al. The Human AC133 Hematopoietic Stem Cell Antigen Is also Expressed in Epithelial Cells and Targeted to Plasma Membrane Protrusions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:5512–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarkaria JN, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, et al. Use of an Orthotopic Xenograft Model for Assessing the Effect of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Amplification on Glioblastoma Radiation Response. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12:2264–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandita A, Aldape KD, Zadeh G, Guha A, James CD. Contrasting in vivo and in vitro fates of glioblastoma cell subpopulations with amplified EGFR Genes Chromosomes. Cancer. 2004;39:29–36. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim T-Y, Zhong S, Fields CR, Kim JH, Robertson KD. Epigenomic Profiling Reveals Novel and Frequent Targets of Aberrant DNA Methylation-Mediated Silencing in Malignant Glioma. Cancer Research. 2006;66:7490–501. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim I, Saunders TL, Morrison SJ. Sox17 Dependence Distinguishes the Transcriptional Regulation of Fetal from Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell. 2007;130:470–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W, Glockner SC, Guo M, Machida E, Wang DH, Easwaran H, Van Neste, Herman JG, Schuebel KE, Watkins DN, Ahuja N, Baylin SB. Epigenetic Inactivation of the Canonical Wnt Antagonist SRY-Box Containing Gene 17 in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Research. 2008;68:2764–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGarvey KM, Fahrner JA, Greene E, Martens J, Jenuwein T, Baylin SB. Silenced tumor suppressor genes reactivated by DNA demethylation do not return to a fully euchromatic chromatin state. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3541–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, et al. Control of Developmental Regulators by Polycomb in Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. 2006;125:301–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beier D, Hau P, Proescholdt M, et al. CD133+ and CD133− Glioblastoma-Derived Cancer Stem Cells Show Differential Growth Characteristics and Molecular Profiles. Cancer Research. 2007;67:4010–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–60. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nuovo GJ, Plaia TW, Belinsky SA, Baylin SB, Herman JG. In situ detection of the hypermethylation-induced inactivation of the p16 gene as an early event in oncogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12754–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8681–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rashid A, Shen L, Morris JS, Issa JP, Hamilton SR. Cpg island methylation in colorectal adenomas. AmJPathol. 2001;159:1129–35. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61789-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim YH, Petko Z, Dzieciatkowski S, Lin L, Ghiassi M, Stain S, Chapman WC, Washington MK, Willis J, Markowitz SD, Grady WM. CpG island methylation of genes accumulates during the adenoma progression step of the multistep pathogenesis of colorectal cancer Genes Chromosomes. Cancer. 2006;45:781–9. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esteller M, Catasus L, Matias-Guiu X, et al. hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation is an early event in human endometrial tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1767–72. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65492-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Esteller M, Sparks A, Toyota M, et al. Analysis of adenomatous polyposis coli promoter hypermethylation in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4366–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cameron EE, Baylin SB, Herman JG. p15(INK4B) CpG island methylation in primary acute leukemia is heterogeneous and suggests density as a critical factor for transcriptional silencing. Blood. 1999;94:2445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Graff JR, Herman JG, Myohanen S, Baylin SB, Vertino PM. Mapping patterns of CpG island methylation in normal and neoplastic cells implicates both upstream and downstream regions in de novo methylation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22322–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lou W, Krill D, Dhir R, et al. Methylation of the CD44 Metastasis Suppressor Gene in Human Prostate Cancer. Cancer Research. 1999;59:2329–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan P, Mühlethaler A, Bourloud KB, Beck MN, Gross N. Hypermethylation-mediated regulation of CD44 gene expression in human neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:129–38. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, Jones PA. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature. 2004;429:457–63. doi: 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shmelkov SV, St Clair R, Lyden D, Rafii S. AC133/CD133/Prominin-1. J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:715–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.