Abstract

Access to patients' inner lives can be expanded and enriched by incorporating the arts and humanities into the clinical encounter. A series of self-portraits created by an artist undergoing induction chemotherapy for leukemia afforded a unique opportunity to concentrate one's gaze upon the patient as a stimulus for reflection on suffering and isolation of patients. Poetry and theater were also invaluable in expanding the physician's awareness of the shared experience of illness. The process highlights the central role of the “New Humanities” in modern medicine, where science informs the arts and the arts inform science and medicine.

William Carlos Williams was a pre-eminent poet of the 20th century. His accomplishments as a writer and poet were truly daunting, especially in light of the demands of his busy career practicing obstetrics and pediatrics. Rather than finding his medical practice a handicap to his creative writing, he believed that medicine fuelled and fired his poetry, allowing him to seize the daily experience of his medical encounters and turn them into verses infused with the passion of life. The importance of poetry for him as well as for all of us is contained in his words:

It is difficult

To get the news from poems

Yet men die miserably every day

For lack

Of what is found there (1).

Williams described the special privilege that physicians possess in their being allowed access to the “secret gardens of the self”- the rich world of their patients' lives that was the source of his poetry. This access is most commonly via the portal of the spoken word, by means of which patients communicate the stories of their lives. Physicians, with their access to stories, become the guardians of their patients' secrets, the clerks of their records, with all the obligations and rewards that arise on entering this territory.

An unusual access to the story of a patient's experience of illness was afforded me following my receipt of a collection of drawings from a leukemia patient for whom I had cared. Aaron, the patient, was a furniture designer and artist who had brought a mirror into his hospital room and sequentially sketched himself while undergoing a successful but grueling course of induction chemotherapy. (Figures 1–15) During his 37-day hospitalization, he created a series of powerful self-portraits that document his journey through the exhausting demands of leukemia treatment—a journey that is an embarkation upon a therapeutic pathway that contradicts the Hippocratic teaching of “primum non nocere.” The territory into which it leads the patient and his loved ones is treacherous and proves demanding, if not overwhelming, for them as well as the health care team.

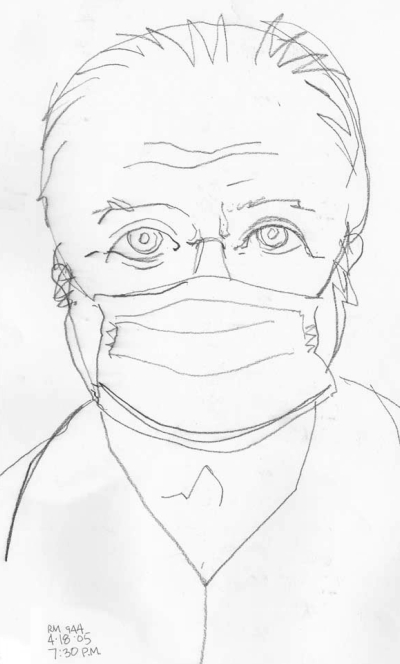

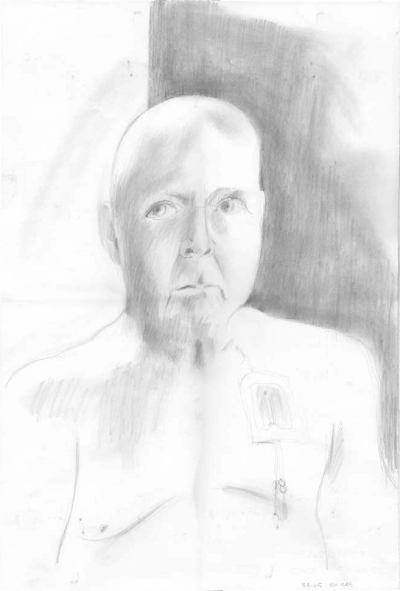

Fig. 1.

Hospital admission for chemotherapy of Acute Myeloid Leukemia.

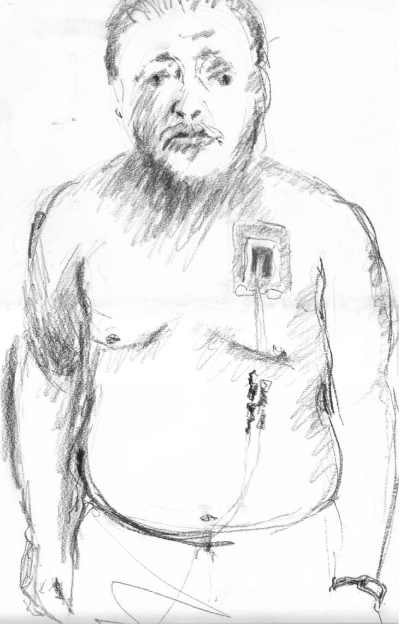

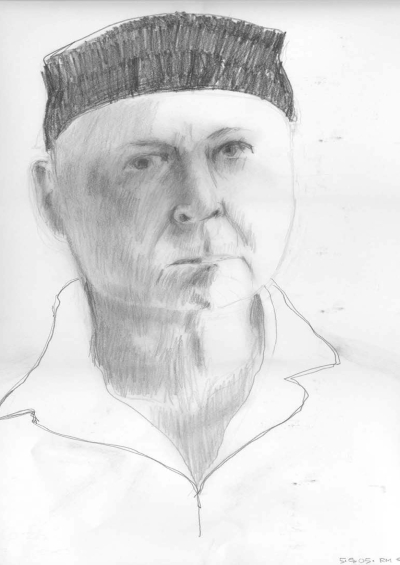

Fig. 2.

Insertion of central catheter for infusions and blood sampling.

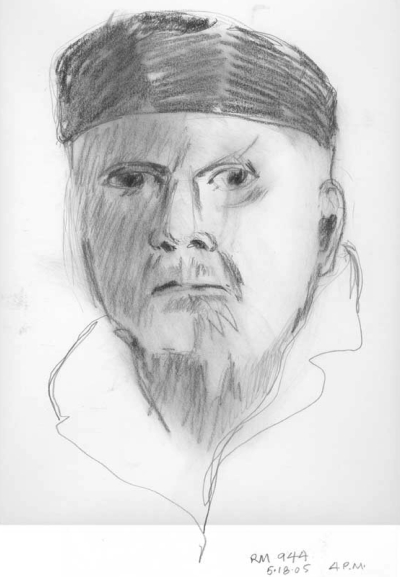

Fig. 3.

Initiation of 7 day course of chemotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Chemotherapy associated with falling blood counts.

Fig. 5.

Leukemic cells cleared from peripheral blood.

Fig. 6.

Fever in setting of low white cell counts antibiotics initiated.

Fig. 7.

Chemotherapy completed.

Fig. 8.

Rash secondary to drug allergy.

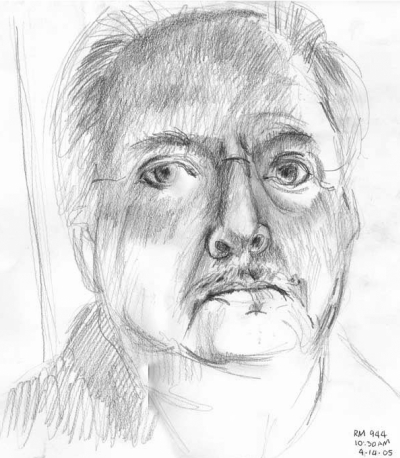

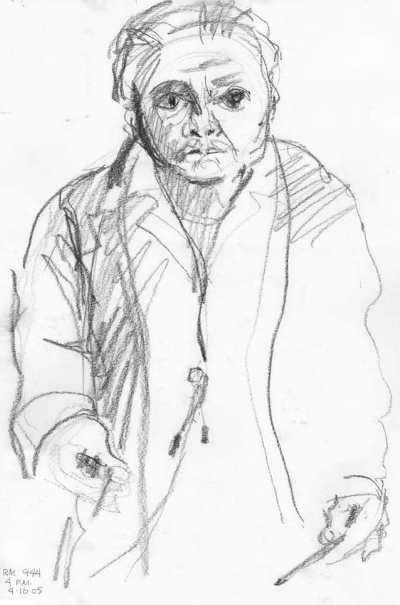

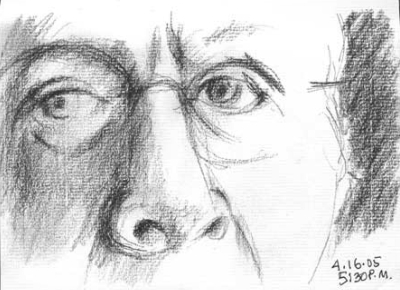

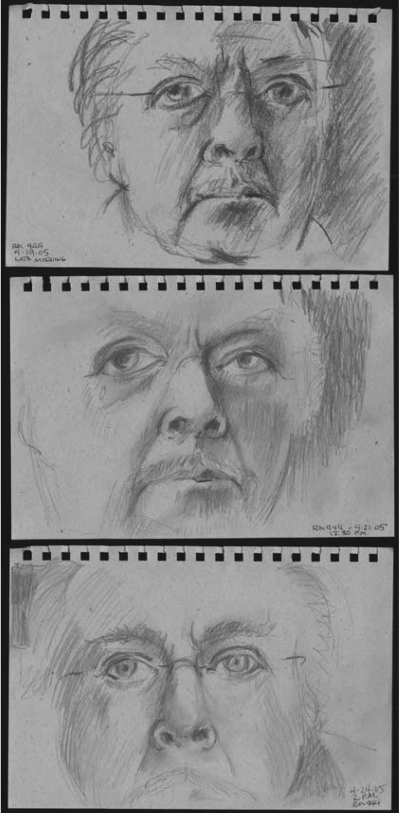

Fig. 9.

Aaron's gaze, days 5, 7, 10.

Fig. 10.

A waiting bone marrow study to determine success/failure.

Fig. 11.

Bone marrow aspiration performed.

Fig. 12.

Persistent leukemia: Initiation of 2nd course of chemotherapy.

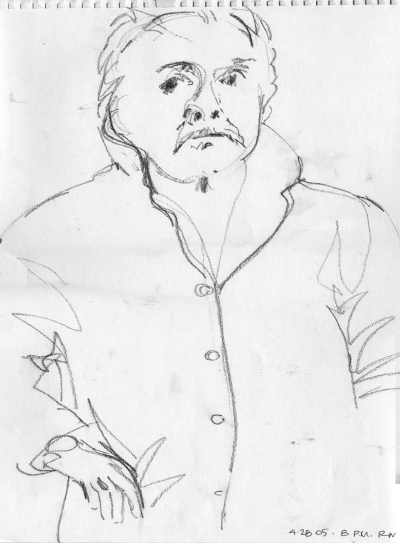

Fig. 13.

Completion of 2nd course of chemotherapy.

Fig. 14.

Severe reduction in cell counts. Red cell and platelet support and antibiotics.

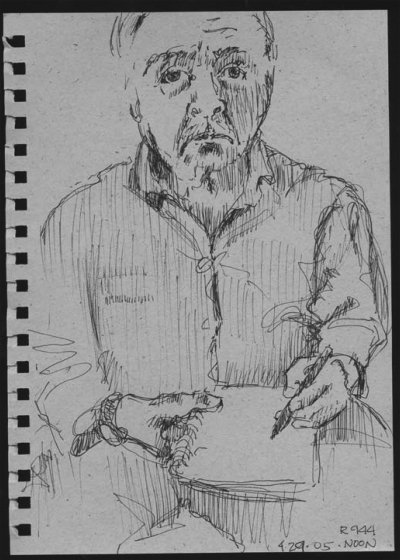

Fig. 15.

Marrow free of leukemia Discharge: Day 37.

Leukemia usually intrudes by stealth into a previously healthy life and fills that life with terror that has its sources in the life-threatening implications of the diagnosis and the life-altering demands of its treatment. The initial hospitalization is always a long one, on average, four to six weeks in length. The physical appearance of the patient is dramatically altered during this time, with hair loss, weight loss, and muscle loss; mobility is also lost because of tethering to an IV pole as a cumbersome third leg.

The initial outcome of the illness is determined by chemotherapy's success or failure in achievement of a remission. Drugs are administered over a period of seven days with the hoped-for goal, the elimination of all leukemia cells from the body. But this desired and necessary goal is not achieved without significant risks and complications. Chemotherapy is not selective in targeting leukemia cells. Normal marrow elements are also eliminated. The lining cells of the gut are razed with attendant nausea, vomiting and diarrhea as well as certain creation of systemic infection. All these complications and threats persist for 14 to 21 days following the initial administration of chemotherapy. Survival is not possible if the leukemia is not eliminated and normal hematopoiesis re-established.

All these assaults are magnified by the need for the patient to be protected from contamination by visitors and staff; all interactions are with masked, gowned, gloved personnel, further accentuating the isolation, both physical and psychological, that envelops the leukemia patient. Just as the body is stripped naked of its resistance to infection, the psyche is often stripped of its defenses by losing the warmth of human presence. A final loss may be the death of the patient in the next room or down the hall, the wail that interfered with sleep in the last few nights.

Aaron's self-portraits of his journey depict all the “stations”, all the challenges that he experienced and overcame. His sketches are unique; no other artist/patient has created a similar body of work. Some artists have created a self-portrait at a single point in time in their illness. Aaron's works depict not only the ravages of illness over time but the therapy-related effects. His portraits are a collage of physical and emotional alterations that parallel the chemotherapy assault upon his bone marrow. For some other artists, the self-portraits are ultimately objects of art in themselves - more an interpretation of illness in artistic form than an expression of the subject's suffering. Aaron's works are simple charcoal sketches, often on pages from a spiral-leaf note book; they served a different purpose than the creation of a piece of art. They served as a form of hope that helped sustain him while he, like other patients undergoing induction chemotherapy, experienced a daily encounter with a possible ending of his life. The sketches are objects that would survive him if his therapy were unsuccessful. They would blur the boundaries between were and are. They differ greatly from the images that most of us are exposed to and are comfortable with; it is the rare patient who chooses to be naked in the surroundings of serious illness. Aaron's sketches afford us a visual entrance into the secret gardens of his self as he was forced to meditate upon his own mortality; his life challenged by leukemia's possession and possible destruction of his body.

A review of Aaron's hospital chart discovers meticulous documentation of his medical course—his blood counts, vital signs, infections, antibiotics—but little regarding Aaron's own battle and the resources that buoyed his spirit during his 37 days of waiting. Aaron, like all other patients in the same circumstances, spent most of his time waiting—waiting for the doctors on rounds, waiting for the results of the daily blood counts, waiting for the completion of chemotherapy, waiting for the outcome of chemotherapy, waiting for the return of marrow function, waiting for life to start again, waiting for life to end-over a course of 37 days. What is it like to wait in these circumstances? And what is it one waits for? How does one try to understand or comprehend the waiting? There is no medical literature on this subject. I turned to an individual whose works are all about waiting—Samuel Beckett. In his ironically titled play, Happy Days, the main character spends the entire play more than half way immersed in a mound; room 944 was Aaron's mound.

Beckett's better know work, Waiting for Godot, is a play that is all about waiting, a waiting for what never comes and the resiliency of two tramps mired in an existential abyss. Early on, an interchange occurs between the two tramps, an interchange that all patients and their physicians must deal with as they confront a serious and life threatening illness.

V. Ah yes, the two thieves. Do you remember the story?

E. No. V. Shall I tell it to you? E. No.

V. It'll pass the time … It was two thieves, crucified at the same time as our saviour.

E. Our what?

V. Our saviour. Two thieves, One is supposed to have been saved and the other …damned.

E. Saved from what?

V. Hell (2).

This banter is an allusion to the words of St. Augustine: “Do not despair, one of the thieves was saved; do not presume, one of the thieves was damned‘.

All patients in the midst of serious illness must choose between these two antipodes. To despair is to lose hope, which is a powerful contributor to the will to survive. To presume is to have vain or unrealizable hope. It is the demanding task of the physician to strive to establish a wise and compassionate balance by nurturing hope but not presumption. The confrontation often proves more complicated and conflicted—even with total self-honesty and benevolent truth-telling, the message may fall on deaf ears. Even if it is false, hope for many patients is unquenchable. For them, false hope is an oxymoron, a contradiction of terms. How can a longing, a wish, an aching desire, ever be false? How can one limit what one is wishing for? The outcome may be bad but one can and must hope for otherwise. Aaron's portraits convey a look of determination that only a spirit of hope could sustain. Aaron was captive-waiting and could have succumbed to despair, but his portraits allowed his sorrow to take wing and escape the confines of room 944. The closing words and inaction of Beckett's Waiting possess a surprising resonance with his state. The insuppressible Chaplinesque duo end with—Well, shall we go? Yes, let's go …but they do not move. Aaron must await the return of his normal marrow but was always eager to go, caught between hope and despair.

Aaron survived one year after his successful treatment for leukemia. Aaron is not here to tell us of his journey. In place of his words, I would like to use the poetry of Jane Kenyon who died of leukemia at the age of 47. Her poetry dwelt with the same simple themes as Robert Frost; in this she was joined by her equally accomplished husband, the poet-laureate, Donald Hall, in focusing on their lives together in a small New Hampshire village. Her most famous poem, “Let Evening Come” was written before she developed leukemia. It is a poem of resignation to the rhythms of life and nature with death as a part of life. The poem's concluding stanza:

Let it come, as it will, and don't

Be afraid. God does not leave us

Comfortless, so let evening come (3).

is an acceptance of death by an individual not confronted by its presence in her immediate life?

Another of her poems, “Otherwise”, contains themes that must flood the mind and emotions of anyone in the midst of dealing with illness of oneself or a loved one. Donald Hall underwent surgery for metastatic colon cancer, and he was discharged home with every expectation that his life was coming to an end. The reality of impending death had entered his life and that of his wife. Ironically, their roles were reversed when his malignancy proved to be cured. His survival made him the caretaker of his caretaker when Jane Kenyon developed leukemia. “Otherwise” details the simple pleasures of their everyday life but concludes with the realization that “one day, I know it will be otherwise” (4).

After Jane Kenyon became ill, her poetry petered to an end. A poet whose work centered upon the splendor of life had a creative standstill, a not uncommon aftermath in the midst of suffering. The details of her illness now have her husband's voice, her anguish multiplied by his massive fear of what awaited both of them with her dying. He has written an epic poem entitled “Without” that dispenses with the equanimity of “let evening come” and replaces it with the plaintive “Timor mortis conturbat me”- the fear of death confounds me (5).

Kenyon and Hall's poems move from a stance of resignation in “let Evening come” to a posture of questioning in “otherwise” to flat-out rejection of death in “Without”. The poems plot a course that is not unlike the trajectory of many patients with terminal illness. There must have been much of “Otherwise” in Aaron's thoughts throughout this process. I suspect he raged against the dying of the light, but it was a conversation we never had. It is easier to discuss the details of chemotherapy and blood counts than to enter the dangerous, precarious, painful, mysterious and fertile regions that Aaron's portraits depict. One cannot examine his portraits without being compelled to try to understand what it is like to look at death, and what is necessary to help accompany a patient on that journey. Aaron's gaze in each of his portraits is an invitation, a command, to witness him and his suffering. To gaze not upon his leukemic cells and all the complicated data of his illness. It is to gaze into his person, even his soul, as he fought for his life. It is his legacy that we extend that gaze to all of the patients in our care.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed

Permission for publication of Aaron's portraits is kindly provided by the patient's family.

DISCUSSION

Kitchens, Gainesville: Thank you for introducing me to our craft of hematology in July of 1973.

Duffy, New Haven: I take pride in you.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams W.C. New York: New Directions; 1994. “Asphodel, that greeny flower & other love poems.”; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckett S. London: Faber and Faber; 1956. “Waiting for Godot: a tragicomedy in two acts.”; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenyon J. St. Paul, Minn.: Graywolf Press; 1990. “Let evening come.”; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenyon J. St. Paul, Minn.: Graywolf Press; 1996. “Otherwise: new and selected poems.”; p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall D. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co; 1998. “Without: poems.”; p. 81. [Google Scholar]