Abstract

Cell shape changes are critical for morphogenetic events such as gastrulation, neurulation, and organogenesis. However, the cell biology driving cell shape changes is poorly understood, especially in vertebrates. The beginning of Xenopus laevis gastrulation is marked by the apical constriction of bottle cells in the dorsal marginal zone, which bends the tissue and creates a crevice at the blastopore lip. We found that bottle cells contribute significantly to gastrulation, as their shape change can generate the force required for initial blastopore formation. As actin and myosin are often implicated in contraction, we examined their localization and function in bottle cells. F-actin and activated myosin accumulate apically in bottle cells, and actin and myosin inhibitors either prevent or severely perturb bottle cell formation, showing that actomyosin contractility is required for apical constriction. Microtubules were localized in apicobasally directed arrays in bottle cells, emanating from the apical surface. Surprisingly, apical constriction was inhibited in the presence of nocodazole but not taxol, suggesting that intact, but not dynamic, microtubules are required for apical constriction. Our results indicate that actomyosin contractility is required for bottle cell morphogenesis and further suggest a novel and unpredicted role for microtubules during apical constriction.

Keywords: Xenopus, bottle cell, apical constriction, cytoskeleton

INTRODUCTION

Cell shape changes and cell movements are essential to diverse processes ranging from formation of embryonic shape during development to cancer cell metastasis. A prevalent type of embryonic cell shape change is apical constriction, in which contraction at the apical surface causes a stereotypical cuboidal-to-trapezoidal shape change. In an epithelial layer, this shape change in a coordinated group of neighboring cells can cause the cell sheet to bend such that the basal surface becomes convex (Lewis, 1947; Odell et al., 1981). Apical constriction is central to gastrulation in invertebrates such as nematodes (Lee and Goldstein, 2003), sea urchins (Kimberly and Hardin, 1998), and fruit flies (Young et al., 1991), as well as to vertebrate morphogenesis, e.g., during neurulation (Burnside, 1971; Haigo et al., 2003; Jacobson et al., 1986), placode formation, and primitive streak formation (Solursh and Revel, 1978). Studying apical constriction may also lead to insights relevant to invasion, a key aspect of metastasis that requires cell shape changes (Rao and Li, 2004).

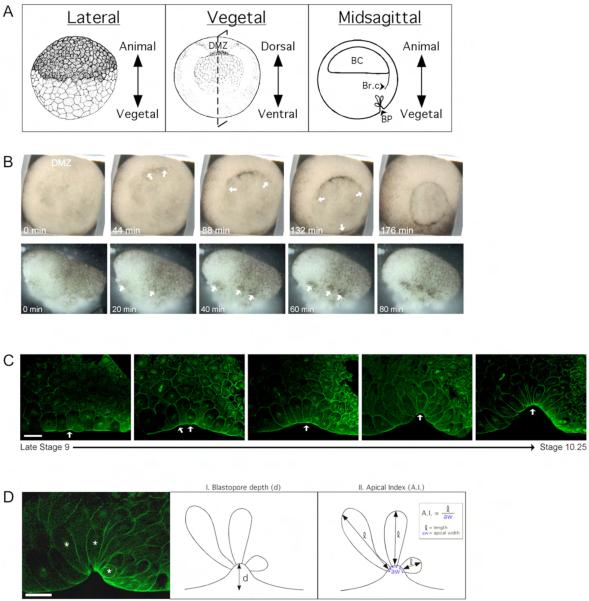

During the initial stages of gastrulation in the amphibian Xenopus laevis, cells in the dorsal marginal zone (DMZ) undergo apical constriction while simultaneously lengthening along the apicobasal axis, transforming from cuboidal to flask-shaped (Fig. 1). These “bottle cells,” readily identified by the accumulation of pigment granules at their apices (Fig. 1B; see Movie 1 in supplementary material), initiate the blastopore lip, creating a crevice for the gastrulating cells to internalize (Fig. 1C) (Hardin and Keller, 1988; Holtfreter, 1943; Keller, 1981). Bottle cell formation initiates in the DMZ and progresses through the lateral and ventral marginal zone to form the circular blastopore (Fig. 1B). They are the first cells of the embryo to undergo dramatic and externally visible changes in cell shape, and represent one of the several distinguishable cell behaviors that comprise gastrulation (Keller et al., 2003).

Fig. 1.

Xenopus laevis bottle cell formation. (A) Embryo Orientation. Lateral illustration (left panel, Stage 8) and vegetal illustration (middle, Stage 10) from Nieuwkoop and Faber series (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1994). Dotted line through vegetal view shows the mid-sagittal plane. Abbreviations: DMZ, Dorsal Marginal Zone; BC, blastocoel; Br.c, Brachet’s cleft; BP, blastopore. (B) Time-lapse images of bottle cell formation in a whole embryo (top) and in a dorsal-lateral marginal zone explant. Time elapsed (in minutes) noted in the bottom left hand corner of each panel. Small arrows point to sites of bottle cell formation. Movies of this embryo and explant can be found in the supplementary materials. (C) Confocal midsagittal images of DMZs stained with α-tubulin antibody from late stage 9 (left) to stage 10.25 (right) showing progression of bottle cell formation (small arrows) and blastopore groove formation. In this and all DMZ midsagittal views, embryos are oriented with vegetal to the left and dorsal side down. (D) Measuring apical constriction. Left panel shows a confocal image of a midsagittal section of a DMZ stained with α-tubulin antibody. Asterisks indicate cells undergoing apical constriction, which are illustrated in middle and right panels. Blastopore depth (d), indicated by the length of the arrow in the middle panel. The right panel illustrates the Apical Index (A.I.), which is the cell length (l) divided by the apical width (aw). Scale bar = 50 μm.

For most of the twentieth century, bottle cells were hypothesized to function centrally in gastrulation by actively migrating into the embryo and dragging the involuting mesoderm with them (Holtfreter, 1943; Rhumbler, 1899; Rhumbler, 1902; Ruffini, 1925). In support of this hypothesis, isolated salamander bottle cells in high pH media exhibit highly motile behavior (Holtfreter, 1943). To test their role in vivo, Keller removed bottle cells from Xenopus embryos and demonstrated that a truncated archenteron (Keller, 1981) and head deformities result, potentially caused by abnormalities in the head mesoderm (R. Keller, personal communication). However, the most striking outcome was that removal of bottle cells resulted in relatively normal gastrulation and neurulation after a delay (Keller, 1981). He therefore concluded that bottle cells were required for the efficient initiation of suprablastoporal endoderm involution. Following involution, the bottle cells line the epithelium of the archenteron, where they respread to form the peripheral archenteron wall (Hardin and Keller, 1988). Even though bottle cells play a lesser role in Xenopus gastrulation than originally proposed, their shape changes are nonetheless necessary for efficient gastrulation. Furthermore, Xenopus bottle cells are an ideal model for studying apical constriction, as the cells are large and accessible. Importantly, one can isolate tissues and culture explants to examine cell behaviors in relative isolation, which allows for the identification of intrinsic versus extrinsic mechanisms. In this paper, we aim to investigate the cell biological basis for apical constriction and the extent to which this cell shape change may generate tissue-bending force.

Some information on the cellular components that control apical constriction has come from forward genetic screens in Drosophila and reverse candidate screens in C. elegans. In the ventral furrow of Drosophila, the G-protein component Concertina (Cta) and associated signaling molecule Folded gastrulation (Fog) are required for the coordination of apical constriction (Sweeton et al., 1991). Strikingly, cells still undergo apical constriction in the absence of these components. Further analysis of chromosomal deficiencies has implicated the accumulation of adherens junctions and RhoGEF2 at the apical surface (Kolsch et al., 2007). During C. elegans gastrulation, the PAR proteins establish apicobasal polarity in ingressing cells (Nance et al., 2003) and Wnt signaling is required to activate actomyosin contractility during apical constriction (Lee and Goldstein, 2003; Lee et al., 2006).

In vertebrate cells, only one protein has been identified whose expression is sufficient and necessary for apical constriction. The Shroom3 gene was initially identified in mice as required for neural tube closure, and subsequently was shown to be the limiting component in apical constriction during Xenopus neurulation (Haigo et al., 2003; Hildebrand and Soriano, 1999). Indeed, expression of the protein in a polarized epithelium is sufficient to cause apical constriction; the constriction is accompanied by the accumulation of actin, and can be disrupted by interference with small G-proteins (Hildebrand, 2005). However, it is still not clear how this mechanism relates to other apical constriction events in vertebrates, such as those occurring in bottle cells, in which Xenopus Shroom is not expressed (Haigo et al., 2003).

Although we are beginning to understand the genetic mechanisms controlling apical constriction in Drosophila, C. elegans, and vertebrate neurulation, there is an opportunity to use a cell biological approach to apply the extensive knowledge of cytoskeletal dynamics in cultured cells to study cell shape changes in vivo. Embryological and scanning electron micrograph studies provided a biomechanical insight into bottle cell function (Hardin and Keller, 1988; Holtfreter, 1943; Keller, 1981), but there has not been any investigation of the cytoskeletal dynamics underlying bottle cell formation. It has been hypothesized that actin and myosin are the major players driving apical constriction, although this has only been conclusively shown in a few cases in other systems (Haigo et al., 2003; Lee and Goldstein, 2003; Young et al., 1991). Early transmission electron micrographs in related amphibians revealed dense material at the apical cortex of bottle cells that were suggestive of actin microfilaments, but this has not been confirmed (Baker, 1965; Perry and Waddington, 1966). Microtubules have not been proposed to play a role during apical constriction, and were found to be dispensable for bottle cell formation (Lane and Keller, 1997), although their structural functions in other contexts suggest that they may participate in bottle cell elongation. Thus, it is unclear what roles the cytoskeleton may play more generally during apical constriction, and more specifically, during Xenopus bottle cell morphogenesis.

In this study, we posed the following questions: First, what do bottle cells contribute to Xenopus gastrulation movements? Second, how are the various cytoskeletal components, such as F-actin, myosin, and microtubules, functioning in apical constriction and apicobasal elongation? Using a combination of embryological manipulation, confocal imaging, cytoskeletal inhibitors, and quantitative analysis, we found that bottle cells play a significant role in gastrulation movements, that actomyosin contractility is required for bottle cell morphogenesis, and that microtubules function in a novel and unpredicted manner during apical constriction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Embryo and explant culturing

In vitro fertilized embryos were de-jellied with 3% cysteine (pH 8.0) and cultured in 1/3 Modified Frog Ringers (Sive et al., 2000). For preparation of explants, the vitelline membrane was removed with forceps on 2% agarose-coated plastic dishes. Explanted tissue was isolated using a combination of hair loops and eyelash knives. Devitellinized embryos and explants were cultured in Danilchik’s for Amy (DFA)(Sater et al., 1993), buffered to pH 8.3 with bicine. Membrane-tethered GFP (pCS2+memE) mRNA (Wallingford and Harland, 2002) was injected dorso-vegetally at the 2- to 4-cell stage, in the area of the future marginal zone.

Phalloidin staining

Embryos were devitellinized and fixed in 4% methanol-free EM-grade paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 1X MEMFA salts (Sive et al., 2000). If applicable, embryos were sectioned midsagittally with a razor blade after one hour of fixation. After fixation, embryos were stained with 5 units/ml Oregon Green phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) resuspended in sonicated PBS plus 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-Tw) overnight and washed twice in PBS-Tw (Haigo et al., 2003), mounted on coverslip-bridged slides in Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA), and sealed with clear nail polish.

Immunostaining

For immunostaining (Sive et al., 2000), embryos were devitellinized and fixed in MEMFA. For microtubule staining, embryos were fixed in 4% PFA in BRB buffer (Gard, 1991). Embryos were usually hand-sectioned midsagittally with a razor blade after one hour of fixation, and then dehydrated in 100% methanol. Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 155 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4) was used instead of PBS, and TBST (1X TBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mg/ml BSA) was freshly prepared for each experiment. Specimens were blocked in 10% normal goat serum diluted in TBST. Primary antibodies used in this study: mouse anti-DM1α(1:500; Sigma, St. Louis, MO); rabbit anti-phospho20 myosin light chain (pMLC, 1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA); rabbit anti-GFP serum (1:500; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR); rabbit anti-β-catenin (1:1000, Sigma); mouse anti-Xenopus nucleoplasmin b7-1A9 (1:1000; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA). The pMLC primary antibody showed a reduction in background staining following two-hours of pre-absorbing with whole fixed embryos. When applicable, we note in the figure legends if pMLC was preabsorbed. All secondary antibodies were used at 1:200: goat anti-mouse FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA); goat anti-rabbit Texas Red (Jackson ImmunoResearch); goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes). After incubation with secondary antibody and subsequent washes in TBST, embryos were dehydrated by rinsing 5-7 times with 100% methanol and cleared with three 10-minute washes in Murray’s clearing reagent (2:1 benzyl benzoate: benzyl alcohol [BB:BA]; Sigma). Embryos were mounted on microscope slides either in BB:BA with a nail polish-sealed coverslip or in four parts Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) to one part BB:BA, and air-dried. Slides were stored at 4°C protected from light. In the course of our experiments, we found that there was a small amount of non-specific staining with the goat anti-rabbit Texas Red secondary antibody, whereas nonspecific staining was absent with the goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (compare Fig. 4A to Fig. 4C).

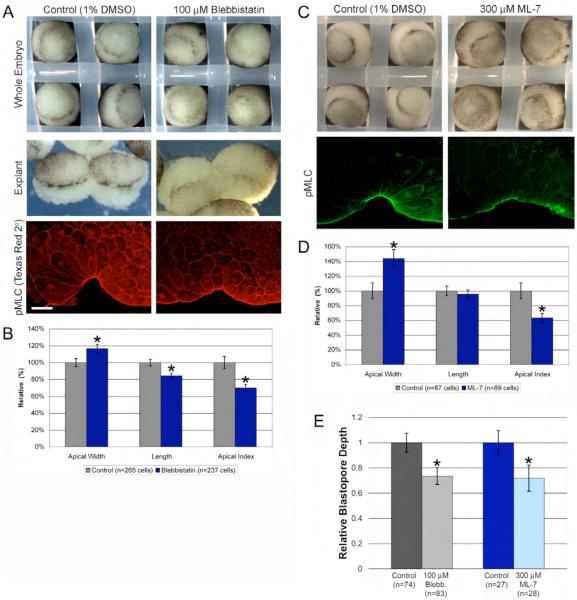

Fig. 4.

Myosin function is required for blastopore groove formation and efficient constriction. (A) Blebbistatin-treated whole embryos (top right) and explants (middle right) make bottle cells but exhibit weak apical constriction compared to control (left panels). Blebbistatin-treated embryos have smaller apical indices than control embryos. Bottom row of pictures show control and blebbistatin-treated embryos immunostained with pMLC primary antibody and Texas Red secondary antibody. The Texas Red secondary antibody results in nonspecific staining, allowing visualization of cell outlines for quantitative analysis (compare with Alexa 488 secondary shown in Figs. 2A, 4C, and Supplementary Fig. 2A,B; see Materials and Methods). (B) Apical width, cell length, and apical index in control versus blebbistatin treated bottle cells. Asterisks denote p ≤ 0.001. (C) ML-7 treatment results in shallower blastopore invagination (top) and reduced pMLC staining. (D) Apical width, cell length, and apical index in control versus ML-7 treated bottle cells. (E) Blebbistatin and ML-7 treatment both result in significantly shallower blastopore depths compared to controls. Error bars = 2X s.e.; p ≤ 0.001 for both control vs. blebbistatin and control vs. ML-7. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Imaging

Whole embryos or marginal zone explants were imaged using a Leica DFC 480 camera (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL), driven by Image Pro Plus 5.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) on a Leica MZ FLIII dissecting microscope. Whole embryos were placed in a one mm2 mesh (Small Parts, Inc., Miami Lakes, FL) in order to image embryos vegetally. Confocal imaging was performed on a Leica DM RE (Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA) with Leica TCS software, version 2.61. For time-lapse imaging of explants, specimens were placed in DFA on a microscope slide, then sealed with a coverslip with clay feet corners and vacuum silicon grease (Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI) at the edges. Time-lapse images were acquired every two minutes and assembled into movie files using QuickTime Pro (Apple, Cupertino, CA). Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Morphometrics

Blastopore depths were measured using Leica TCS software or ImageJ1.34S (Wayne Rasband, NIH, Bethesda, MD). Pixel intensities, cell length, and apical width measurements were performed using ImageJ1.34S. Quantitative and statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). T-tests were used to determine significance. All error bars represent 2x standard error measurement, as this approximates the 95% confidence interval.

Pharmacological inhibitors

All inhibitors were obtained from Calbiochem (EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA), except paclitaxel (taxol), which was supplied by Sigma. Inhibitors were diluted in DFA, at the following final concentrations: 1 μM latrunculin B, 10 μM cytochalasin D, 100 μM blebbistatin (in 90% DMSO), 300 μM ML-7, 15 μg/ml nocodazole, 20 μg/ml taxol. All drug experiments were performed with 1% DMSO in DFA as the carrier control except taxol, where 0.5% DMSO was used. At least three sets of experiments were performed for all drugs except ML-7, with the total number of embryos or cells analyzed listed in each figure. ML-7 treatment was not consistently effective, as indicated by an insignificant decrease in pMLC signal compared to controls. Only those experiments where the pMLC apical pixel intensity was significantly lower in ML-7 treated embryos (compared to controls) were analyzed for blastopore depth (two out of six experiments).

RESULTS

Xenopus laevis bottle cell formation

Bottle cells start forming in the DMZ of stage 10 embryos and this shape change continues to occur in the lateral and ventral marginal zone cells until a circular blastopore is formed (Fig. 1B; see Movie 1 in supplementary material). It was shown previously that bottle cells could form in explanted marginal zone tissue (Hardin and Keller, 1988). We repeated those experiments with the goal of using explants as a tool to study apical constriction in bottle cells in relative isolation, removed from the forces of other gastrulation machinery such as epiboly and vegetal rotation (Keller et al., 2003). After isolating marginal zone explants, we removed large portions of both the involuting marginal zone, which undergoes convergence and extension (Keller and Danilchik, 1988; Keller et al., 1992; Keller et al., 1985), and the vegetal endoderm, which participates in vegetal rotation (Winklbauer and Schurfeld, 1999). Time-lapse imaging shows that bottle cells form in explants, with the same timing and marginal zone pattern as in intact embryos (Fig. 1B; see Movie 2 in supplementary material). Consistent with previous observations (Hardin and Keller, 1988) we also saw that instead of a sequential “spreading” of bottle cell formation and invagination, cell shape changes occurred in distinct clusters in both explants and whole embryos (see Movies 2 and 3 in supplementary material). Between these constriction sites, cells were stretched (see Movie 3 in supplementary material), suggesting that some populations of bottle cells start constricting and invaginating earlier than other groups.

To study the extent of apical constriction and cell elongation in bottle cells, we measured two sets of parameters. First, as an indirect measure of the deformation of the tissue caused by bottle cell apical constriction, we measured the blastopore depth (Fig. 1D). In a second, more direct measurement of cell morphology, we measured the length and apical width of bottle cells in the manner of Hardin and Keller (Fig. 1D)(Hardin and Keller, 1988). The length over apical width results in an “apical index.” A perfectly cuboidal cell has an apical index of one, whereas a bottle cell, undergoing apical constriction and cell elongation, usually has an apical index ranging from five to seven (Supplementary Fig. 3). In our analyses, a bottle cell is defined as being a cell that is in the blastopore groove and has an apical index much greater than one. A non-bottle cell is a cell outside of the invaginating blastopore and has an apical index of approximately one. A pre-bottle cell is any cell that is in the marginal zone, defined by its intermediate size in relation to the smaller cells animally and the larger cells vegetally.

Embryos without DMZ bottle cells exhibit a delay in initial gastrulation movements, but are then able to resume morphogenesis and complete both gastrulation and neurulation (Keller, 1981). Therefore, bottle cells contribute to the efficiency of gastrulation initiation, but it is unclear how their shape changes contribute to bending the tissue, especially since other morphogenetic processes begin around the same time. To assess the contribution of the bottle cells to the initial formation of the blastopore lip, we isolated DMZ explants and compared their blastopore depths with intact embryos to assess how much deformation bottle cells could cause in relative isolation. Hardin and Keller had previously shown that apical constriction, but not apicobasal elongation, was an intrinsic bottle cell behavior (Hardin and Keller, 1988). We asked how this intrinsic apical constriction contributes to the initial blastopore invagination. We fixed devitellinized embryos and DMZ explants 30 minutes and 60 minutes after bottle cells were first observed, then measured the blastopore depth in midsagittal sections. At both time points, whole embryos, on average, had a slightly deeper blastopore than explants. However, the differences in blastopore depths between explants and whole embryos were not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 1). Although we did not assess the different contributions of adhesion, tissue tension, and wound healing in explants versus embryos, these data suggest that bottle cell shape change can account for much of the initial invagination of the blastopore.

F-actin and activated myosin accumulate apically in bottle cells

How is the cytoskeleton changing the shape of bottle cells? One hypothesis is that apical constriction in Xenopus bottle cells is driven by actin and myosin. We therefore examined F-actin and myosin localization in bottle cells. Embryos stained with Oregon-green conjugated phalloidin showed an intense accumulation of F-actin at the apical surface of bottle cells (Fig. 2A). To observe activated myosin localization, we immunostained embryos with an antibody against phosphorylated myosin regulatory light chain (pMLC), where phosphoserine 19 marks activation. Like F-actin, activated myosin was also intensely localized to the apical surface of bottle cells (Fig. 2A). Three observations support the specificity of the anti-pMLC antibody in Xenopus laevis. First, when the primary antibody was omitted, there was an absence of staining (Supplementary Fig. 2A,B). Second, a□□ pMLC marked expected sites of myosin function during mitosis, such as the pre-furrowing membrane at anaphase and the cytokinetic furrow (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Finally, when embryos were cultured in ML-7, a small inhibitor of myosin light chain kinase, the levels of pMLC staining significantly decreased compared to control embryos (Fig. 4C).

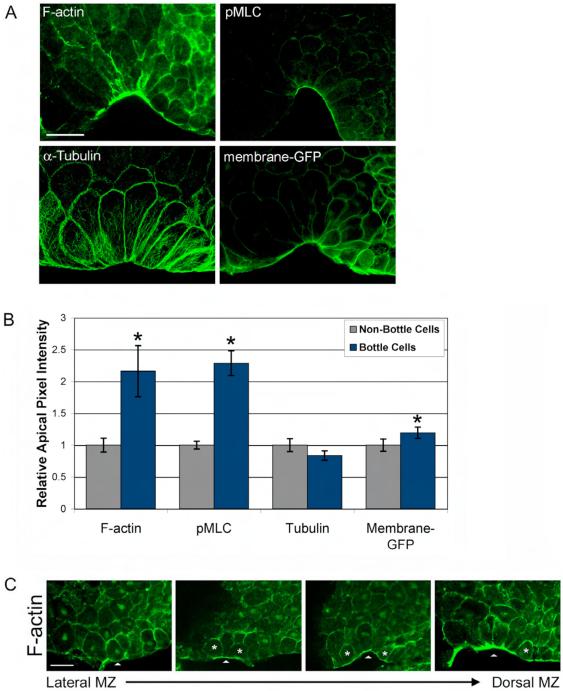

Fig. 2.

Significant F-actin and activated myosin accumulation occurs at the apical surface of bottle cells. (A) Confocal, midsagittal sections of DMZs stained for F-actin (Oregon green-conjugated phalloidin), activated myosin (anti-pMLC), α-tubulin (anti-DM1α), and memGFP (anti-GFP). (B) Quantification of pixel intensity at the apical surface of bottle cells and non-bottle cells. Asterisks above bottle cell bars indicate p-value < 0.05 compared to non-bottle cells of same staining. Error bars = 2X standard error (s.e.). For morphometrics of cells analyzed, see Supplementary Fig. 3. The following numbers of cells were measured for each subgroup (bottle cells and non-bottle cells number were equivalent): F-actin, 66; pMLC, 66; tubulin, 34; memGFP, 54. (C) Confocal, midsagittal sections of DMZ’s stained for F-actin (Oregon green-conjugated phalloidin). Arrowhead points to marginal zone, and asterisks indicate cells that are accumulating F-actin at their apical membranes without significant cell shape changes. Panels from left (Lateral MZ) to right (Dorsal MZ) represent transition from non-bottle cells to early bottle cells. Scale bar = 50 μm.

To assess whether bottle cells significantly accumulate actin and myosin at their apical surfaces, we measured mean apical pixel intensity, apical width, and apical index of F-actin- and pMLC-stained bottle cells and non-bottle cells. For controls, we quantified α-tubulin levels, as microtubules represent cytoskeletal proteins not predicted to localize to the apical membrane, and anti-GFP in embryos injected with membrane-tethered GFP (memGFP) as a ubiquitous membrane marker. F-actin, pMLC, and memGFP all exhibited significantly higher apical pixel intensity in bottle cells compared to their non-bottle cell counterparts, whereas there was no significant difference in tubulin staining between bottle cells and non-bottle cells (Fig. 2B). However, the difference in apical intensity of F-actin and pMLC between bottle versus non-bottle cells is much higher than that of memGFP (Fig. 2B). These differences are not due variation in cell morphometrics, as the apical indices were not statistically different between the four groups (Supplementary Fig. 3). Together, this analysis suggests specific apical accumulation of F-actin and pMLC in bottle cells.

One formal possibility is that actin and myosin passively accumulate at cell apices during constriction, and are not actively involved in apical constriction. Two pieces of data argue against this possibility. First, phalloidin staining of lateral marginal zones ( “pre-bottle cells”) showed apical F-actin accumulation preceding bottle cell formation (Fig. 2C). Second, X-Y scatter plots graphing log10 values of intensity versus apical width in F-actin- and pMLC-stained embryos show no positive correlation between the two parameters (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, it is unlikely that apical accumulation of actin and myosin is a by-product of a shrinking apical surface. Instead, our data suggest that F-actin and pMLC localization precedes and therefore may be functioning in apical constriction.

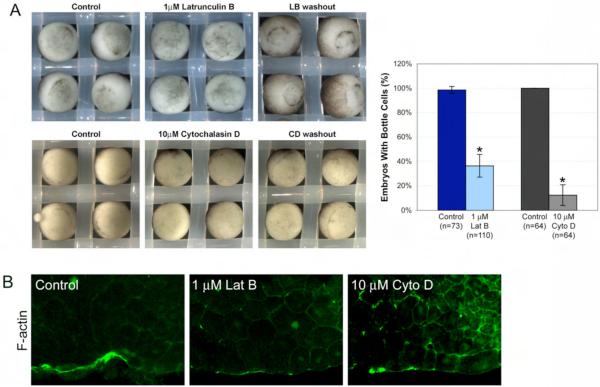

F-actin is required for bottle cell formation

F-actin localization to the apical surface of bottle cells suggests a function during apical constriction. To test whether F-actin is required for apical constriction, we perturbed F-actin structure and dynamics with the pharmacological inhibitors latrunculin B (LB), which depolymerizes F-actin, and cytochalasin D (CD), which prevents polymerization of F-actin. LB and CD treatment were most effective when embryos were exposed to the drugs at least 30 to 40 minutes before stage 10, perhaps due to the large network of apical actin present even before apparent cell shape change (Fig. 2C). Bottle cells were scored by the presence of pigmented invaginating cells at the marginal zone, along the presumptive blastopore. (For all other inhibitors, timing of treatment did not appear to be as crucial.)

In Xenopus oocytes, 10 μM LB effectively depolymerizes F-actin without significant side effects (Benink and Bement, 2005). In contrast, we found that 10 μM LB in stage 9 to stage 10 embryos resulted in toxic and irreversible side effects such as cell de-adhesion and apoptosis (data not shown). Therefore, we used a 10-fold lower concentration of LB (1 μM), which, while perhaps suboptimal for depolymerization of F-actin, was less toxic and was reversible after drug washout (Fig. 3A). In LB, 36.4% of embryos made bottle cells (40 out of 110 embryos, 5 experiments; Fig. 3A), compared to 98.6% of control embryos (72 out of 73). Nearly all LB-treated embryos exhibited randomly invaginating cells, constricting in unorganized pockets across the vegetal side instead of circumferentially along the marginal zone. Due to the possible suboptimal concentration of LB, these cells may represent the potential for randomized contractility in the absence of F-actin. They could also represent cells undergoing the first steps of apoptosis.

Fig. 3.

F-actin is required for bottle cell formation. (A) Actin inhibitors latrunculin B (top) and cytochalasin D (bottom) reversibly prevent bottle cell formation. Control embryos were in 1% DMSO. Bar graph shows percent of embryos making bottle cells in the presence of DMSO control or inhibitor. n, number of embryos. Error bars = 2X s.e. (B) F-actin distribution as indicated by Oregon green-conjugated phalloidin in control, latrunculin B, and cytochalasin D-treated embryos.

Cytochalasin B (CB), an analog of CD, blocked bottle cell formation about half the time (Nakatsuji, 1979). However, CB is no longer favored as a microfilament inhibitor due to its effect on glucose uptake (Ebstensen and Plagemann, 1972). Therefore, we used CD, which more specifically and reversibly inhibits F-actin dynamics. Only 12.5% of the embryos exposed to 10 μM CD made bottle cells (8 out of 64, 3 experiments; Fig. 3A), compared to 100% of control embryos (64 out of 64). Like LB, CD-treated embryos also made bottle cells upon washout of the drug, showing that the effect of the drug was reversible (Fig. 3A). To confirm that LB and CD were affecting F-actin, we stained drug-treated embryos with phalloidin. Consistent with its role as an F-actin depolymerizer, LB-treated embryos exhibited decreased overall F-actin staining and little to no apical accumulation in bottle cells (Fig. 3B). CD caps microfilament plus ends, preventing polymerization. Accordingly, F-actin staining was not completely abolished in CD-treated embryos, although there was a decrease in apical accumulation of F-actin (Fig. 3B). Together, these actin inhibitor experiments argue that F-actin is required for bottle cell formation.

Myosin function is required for efficient constriction

To determine if myosin is also required for apical constriction in bottle cells, we perturbed myosin function using two inhibitors, blebbistatin and ML-7. Blebbistatin is a small molecule inhibitor of myosin motor function (Straight et al., 2003). In the presence of 100 μM blebbistatin, embryos and explants make bottle cells but exhibit weak apical constriction, as evidenced by lighter pigmented bottle cells in both whole embryos and explants (Fig. 4A). To examine the extent to which bottle cell formation is compromised, we measured the apical index and blastopore depth of control and blebbistatin-treated embryos. The apical index was significantly reduced in blebbistatin-treated embryos compared to control embryos (Fig. 4B). The lower apical index was a result of both an increase in apical width and a decrease in length in the blebbistatin-treated bottle cells (Fig. 4B). We also found that the relative blastopore depth was significantly shallower in blebbistatin-treated embryos (73.5 ± 3.3%; Fig. 4E).

Previous reports showed that blebbistatin affects neither actin or myosin localization, nor the phosphorylation state of myosin (Kovacs et al., 2004; Straight et al., 2003). We confirmed that there was no difference in F-actin or pMLC localization in bottle cells in blebbistatin-treated embryos compared to control embryos (Fig. 4A and data not shown). To verify that blebbistatin was inhibiting myosin motor function, we looked for evidence of failed cytokinesis. In animal caps treated with blebbistatin, we observed a significantly higher number of multinucleate cells (Supplementary Fig. 5). These data support a role for blebbistatin in specifically inhibiting myosin motor function, and suggest that myosin is required for apical constriction in bottle cells.

To test myosin function during apical constriction in a blebbistatin-independent manner, we perturbed myosin function with ML-7, an inhibitor of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (Saitoh et al., 1987). Like blebbistatin-treated embryos, embryos treated with 300 μM ML-7 had blastopore depths that were approximately 30% shallower than in control embryos (Fig. 4C,E). ML-7 treated embryos also had bottle cells with reduced apical indices, though only apical constriction was affected (Fig. 4D). To assess whether ML-7 was inhibiting MLCK, we stained control and ML-7-treated embryos with anti-pMLC with the rationale that pMLC levels should decrease in the presence of ML-7. Indeed, we saw a significant decrease in apical pMLC staining in ML-7 treated embryos relative to controls (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that ML-7 inhibits MLCK function, which is then required for apical constriction. We note the following caveats with the ML-7 treatment. First, ML-7 did not reliably inhibit MLCK in all experiments. Therefore, experiments were only analyzed when pMLC levels were significantly decreased (see Materials and Methods). Second, even when pMLC levels were reduced by ML-7 treatment, some pMLC staining persists. This suggests that either ML-7 did not efficiently inhibit MLCK, or that MLC is being phosphorylated by an additional kinase, as it has been shown that MLC can be phosphorylated at serine 19 by MLCK, Rho kinase, and p21-activated kinase (Bresnick, 1999). To address this possibility, we attempted to inhibit Rho kinase activity with Y-26732. We found Y-26732 treatment could not inhibit bottle cell formation (data not shown). However, Y-26732 treatment did not in reduce pMLC staining, even in concentrations as high as 50 μM, suggesting that Y-26732 was unable to effectively inhibit phosphorylation/activation of myosin light chain in bottle cells. Together, the blebbistatin and ML-7 results show that myosin activity contributes to the apical constriction of Xenopus bottle cells.

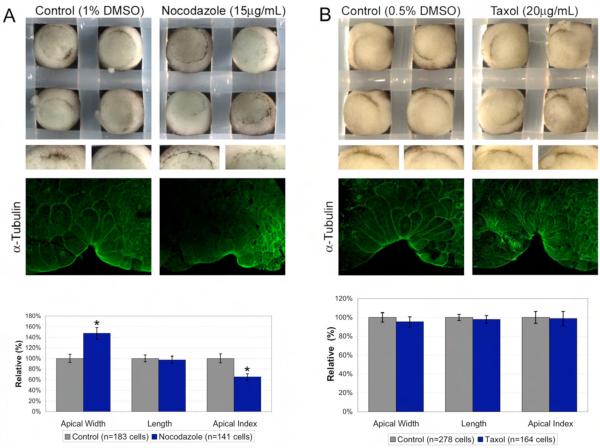

Intact microtubules are required for efficient apical constriction, but not elongation, of bottle cells

As bottle cells form, they undergo both apical constriction and apicobasal elongation. Due to their role in maintaining cell structure, it may be possible that microtubules are required for bottle cell elongation. In bottle cells, α-tubulin localizes to filaments at the apical surface that project in an apicobasal direction (Fig. 2A). Previously, nocodazole and taxol treatments of early gastrula (stage 10-10.5) did not prevent formation of bottle cells (Lane and Keller, 1997). However, it is possible that even though bottle cells form, their constriction and/or elongation may be compromised. To test what role microtubules play in bottle cell formation, we perturbed microtubule dynamics with nocodazole, a tubulin depolymerizer, and taxol, which prevents microtubule plus-end polymerization. As observed previously, nocodazole treatment did not prevent bottle cell formation, but the bottle cells that formed did not invaginate (Fig. 5A). Indeed, midsagittal sections revealed shallower blastopores when compared to control embryos, and nocodazole-treated bottle cells appeared less constricted. Morphometric analysis of bottle cells showed that nocodazole-treated bottle cells had a significantly smaller apical index (65 %) relative to control bottle cells (100%; Fig. 5A). This difference in apical index was not due to the difference in cell length between the control and drug-treated group. Instead, the apical width was significantly larger in nocodazole-treated bottle cells (147.2 %) than in control bottle cells (100 %; Fig. 5A). This suggests that intact microtubules are not involved in apicobasal elongation but that they contribute to apical constriction.

Fig 5.

Intact microtubules are required for efficient apical constriction, but not elongation, of bottle cells. (A) Nocodazole affects bottle cell formation by affecting apical constriction. Middle panels show morphological differences between the bottle cells forming in control versus in nocodazole-treated embryos. Nocodazole treatment disrupts α-tubulin staining. Bar graph shows quantitation of bottle cell morphology. Only apical width and apical index are significantly different in presence of nocodazole (p ≤ 0.0001). (B) Taxol stabilizes microtubules (see also Supplementary Fig. 6) without affecting blastopore formation or bottle cell morphology. Error bars = 2X s.e.

Next, we asked whether it was microtubule dynamics or filament structure that was required for apical constriction. We exposed embryos to taxol, which perturbs microtubule dynamics without destroying existing microtubule filaments. We note that when referring to microtubule “dynamics”, we are referencing the well-documented effects of these inhibitors on microtubules. We did not analyze microtubule dynamics in vivo following drug treatment, but we confirmed that the inhibitors were functional by immunostaining treated embryos with anti-α-tubulin antibody. Unlike nocodazole-treated embryos, taxol treatment did not affect bottle cell formation or invagination in whole embryos (Fig. 5B). Upon morphometric analysis, we found that there were no statistically significant differences between taxol-treated and control bottle cells in apical width, apicobasal length, or apical index (Fig. 5B). As evidence that taxol was affecting microtubule dynamics, we found persistent asters in vegetal cells (Supplementary Fig. 6) and more apicobasal filaments in bottle cells indicating stabilized microtubules (Fig. 5B). Together with the nocodazole data, these results suggest that microtubules do not appear to play a role in bottle cell elongation. Instead, intact, but not dynamic, microtubules are required for efficient apical constriction.

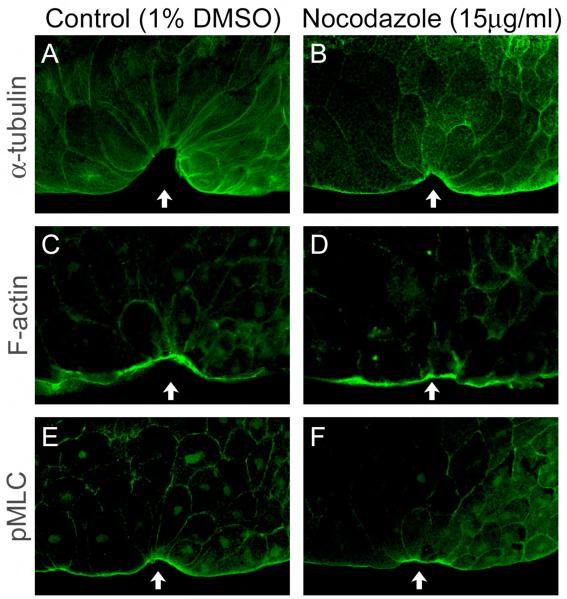

The effect of microtubule depolymerization on F-actin and pMLC localization

As microtubule depolymerization by nocodazole has been shown to affect microfilament contractility (Liu et al., 1998), our nocodazole results could be due to an indirect affect on actin. We tested whether nocodazole treatment affected F-actin localization in bottle cells. As above, nocodazole-treated embryos had lower levels of α-tubulin staining than control embryos (Fig. 6A,B). We stained control and nocodazole-treated embryos with phalloidin and observed that drug-treated bottle cells showed F-actin localization that was indistinguishable from control bottle cells (Fig. 6C,D). In addition, these data suggest that at least some aspects of apicobasal polarity have not been disrupted by nocodazole treatment, as F-actin accumulated apically in both control and drug-treated embryos.

Fig. 6.

Nocodazole treatment does not disrupt F-actin accumulation or MLC phosphorylation. Embryos were cultured in 1% DMSO control (A, C, E) or 15 μg/ml nocodazole (B, D, F), then fixed and stained with anti-α-tubulin (A, B), phalloidin (C, D), or anti-pMLC (E, F). Small arrows point to center of marginal zone (presumptive blastopore).

Another possible explanation for how microtubules may be involved in contraction is through phosphorylation of MLC. In MCF-7 and CHO cells, intact microtubules are required for the MLC phosphorylation that maintains cadherin localization to cell-cell contacts (Stehbens et al., 2006). We immunostained nocodazole-treated embryos with anti-pMLC and found that MLC was phosphorylated at the apical surface of bottle cells in both control and nocodazole-treated embryos (Fig. 6E,F). Thus, microtubule depolymerization by nocodazole does not affect localization of F-actin or pMLC, suggesting that the contribution of microtubules to apical constriction is independent of actomyosin localization and contractility.

DISCUSSION

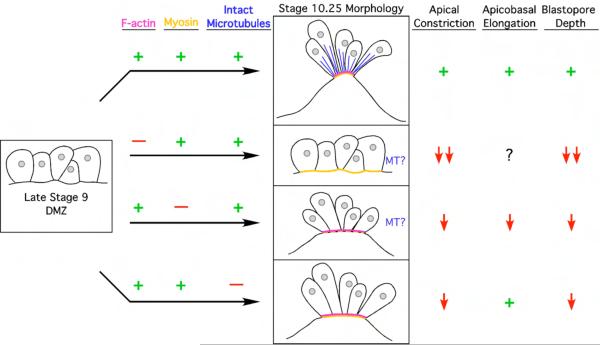

Cell shape changes are critical for embryonic morphogenesis, but the mechanisms underlying changes in cell morphology remain poorly understood, especially in vertebrates. At the beginning of Xenopus laevis gastrulation, bottle cells undergo apical constriction and apicobasal elongation. Comparing isolated embryo explants to intact whole embryos, we found that apical constriction of bottle cells can generate the force required for initial blastopore formation (Supplementary Fig. 1). To determine how the cytoskeleton causes bottle cell formation, we investigated the localization and function of actin, myosin, and microtubules. F-actin and activated myosin accumulate on the apical surface of bottle cells (Fig. 2), consistent with the hypothesis that an actomyosin machine drives apical constriction. To test whether actin and myosin function to contract bottle cell apices, we subjected embryos to the actin inhibitors cytochalasin D and latrunculin B and to the myosin inhibitors blebbistatin and ML-7. The actin inhibitors prevented bottle cell formation in a majority of embryos (Fig. 3), whereas in the presence of the myosin inhibitors, bottle cells still formed but constriction was significantly affected (Fig. 4), confirming that both actin and myosin are required for bottle cell apical constriction. To inhibit microtubule dynamics, we cultured embryos in nocodazole, a microtubule depolymerizer, and taxol, which stabilizes microtubules and prevents polymerization. We found that apical constriction was inhibited in the presence of nocodazole but not in taxol, suggesting that intact but not dynamic microtubules are required for apical constriction (Fig. 5). To determine how microtubule depolymerization may affect constriction, we examined F-actin and pMLC distribution after nocodazole treatment and observed that both proteins were properly localized (Fig. 6). Therefore, microtubule function during apical constriction is independent of F-actin or activated myosin. Our results (summarized in Fig. 7) suggest that actin and myosin function in an apically localized contractile network that is required for bottle cell morphogenesis and further suggest a novel role for microtubules during apical constriction.

Cytoskeletal mechanism of apical constriction and a novel role for microtubules

By combining imaging of protein localization with the use of inhibitors, we have been able to address the cytoskeletal requirements for apical constriction in Xenopus bottle cells. This is one of the very few examples in vertebrate development of actin and myosin being actively required for apical constriction and the first time in any organism that microtubules have been implicated in apical constriction. Having a better understanding of the cellular mechanisms required for apical constriction, we can now begin to probe the upstream molecules that control cell shape changes.

Our microtubule inhibitor results add to the instances where microtubule structure may be more important than microtubule dynamics. During the beginning of Xenopus laevis convergent extension movements, embryos are sensitive to nocodazole treatment but not to taxol (Lane and Keller, 1997). Microtubule mass is required for the stabilization of actin-rich lamellipodia that are necessary for alignment and migration of the cells (Kwan and Kirschner, 2005). This microtubule-dependent stabilization is mediated by XLfc, a microtubule-binding Rho-GEF (Kwan and Kirschner, 2005). In the case of bottle cells, actin localization and dynamics do not appear to be inhibited by nocodazole treatment (Fig. 6), although it is possible that a microtubule-independent Rho-GEF may function in regulating actin dynamics. During Xenopus neurulation, the actin-binding protein Shroom3 coordinates both apical constriction and apicobasal heightening (Lee et al., 2007). Knockdown of Shroom3 disrupts γ-tubulin localization, microtubule filament organization, and apicobasal heightening in neural tube cells (Lee et al., 2007), highlighting the importance of microtubule structure in apicobasal elongation. In contrast, our results do not implicate microtubule structure in bottle cell elongation; rather, we find that intact microtubules are required for apical constriction. Therefore, it appears that the mechanism of cell elongation differs between bottle cells and neural tube cells.

It is well-documented that microtubules are an integral component of intracellular transport, especially in the trafficking of proteins from the trans-Golgi network to the apical membrane of epithelial cell lines (Matter et al., 1990; Rodriguez-Boulan et al., 2005). It is possible that microtubules also act in vesicle transport in bottle cells, either for endocytosis of the apical membrane or for transport of proteins required for constriction to the apical surface. In support of this notion, membrane-bound vesicles were observed in the subapical region of bottle cells (Baker, 1965; Perry and Waddington, 1966). Finally, microtubules have been implicated in cell adhesion (Stehbens et al., 2006), and as the role of adhesion in bottle cells has not been tested, it is possible that microtubules affect contractility through adhesion. These possibilities await experimental tests.

Perry and Waddington hypothesized that bottle cell apical constriction is a passive byproduct of cell elongation (Perry and Waddington, 1966). Blebbistatin treatment affected both constriction and elongation (Fig. 4B), suggesting that both aspects of bottle cell shape changes are myosin-mediated. However, nocodazole treatment affected apical constriction but not apicobasal elongation (Fig. 5). This suggests that apical constriction and apicobasal elongation are not interdependent events, but that separate cytoskeletal machinery controls each process.

Implications and future directions

Clearly, it would be an exaggeration to state that the cellular mechanisms controlling Xenopus bottle cell shape changes are universal and applicable to every case of apical constriction. It is likely that some cells use adhesion or extracellular matrix to constrict (Lane et al., 1993), while other cells employ actomyosin contractility and intact microtubules. In the most well-studied cases, actomyosin localization and contractility play central roles in apical constriction, and the molecular control of constriction varies widely, ranging from Wnt signaling (Lee et al., 2006), to heteromeric G-proteins (Barrett et al., 1997), to the Shroom proteins, a novel class of actin-binding proteins in vertebrates (Haigo et al., 2003; Hildebrand, 2005; Hildebrand and Soriano, 1999; Lee et al., 2007; Yoder and Hildebrand, 2007). Most of these molecular controls were identified using forward- or reverse-genetic approaches that may not identify overlapping or redundant cell biological contributions, and may not be sufficiently sensitive to reveal subtle defects, such as the requirement of intact microtubules for efficient apical constriction. Therefore, our experiments show the value of a bottom-up approach, using small molecule inhibitors at a discrete timepoint, applying cell morphometrics, and statistically analyzing these measurements in order to identify the contribution of cytoskeletal proteins during apical constriction. By obtaining a clearer picture of the cellular mechanisms of apical constriction, we hope to continue to gain new insights into how cells change their shape in development and disease.

Supplementary Material

Movie 1: Time-lapse images of bottle cell and subsequent blastopore formation in a Xenopus laevis embryo, vegetal view. The embryo is oriented with dorsal side to the top left (as seen in the first frame). Bottle cells first appear in the dorsal marginal zone, then spread laterally and ventrally to form the blastopore. Frames were taken every two minutes, with total elapsed time of four hours. Playback is at 10 frames per second.

Movie 2: Time-lapse images of bottle cell formation in a marginal zone explant, cultured in DFA. In explants, bottle cells appear to constrict in clusters rather than sequentially spreading from one side of the embryo to the other. Frames were taken every two minutes, with total elapsed time of two hours. Playback is at 10 frames per second.

Movie 3: Time-lapse confocal images of bottle cell formation in an intact embryo expressing membrane-GFP. Constricting cells, with their surface area shrinking, invaginate into the embryo in clusters, while the cells between them are stretched. Frames were taken every two minutes, with total elapsed time of 86 minutes. Playback is at 10 frames per second.

Fig. 7.

Summary and model of the cytoskeletal mechanisms of Xenopus bottle cell formation. DMZ cells at stage 9 (left) are cuboidal. In unperturbed bottle cells, F-actin (fuchsia) and myosin (orange) are apically localized and intact microtubules (blue) emanate from the apical side, and bottle cells undergo apical constriction and apicobasal elongation while blastopore depth increases as one result of cell shape changes (top row). When F-actin dynamics are inhibited (second row), F-actin does not accumulate apically while pMLC localization is undisturbed (data not shown). Bottle cells do not apically constrict without F-actin, nor do they invaginate to increase blastopore depth. In the presence of myosin inhibitors (third row), F-actin localization still occurs, while pMLC localizes apically in blebbistatin but is reduced in ML-7 treatment. All aspects of bottle cell formation and blastopore depth are disturbed. Nocodazole treatment (bottom row) does not affect F-actin or pMLC localization. Bottle cells without intact microtubules undergo apicobasal elongation normally, but do not apically constrict efficiently, nor do they exhibit significant blastopore depths compared to untreated embryos. Plus signs mean the protein is functional (left columns) or that the event occurs normally (right columns). Minus sign indicates the activity or structure of the protein has been perturbed with inhibitors. Down arrows signify a reduction in cell shape change or decrease in blastopore depth. Question marks indicate unknown results, as those experiments or analyses were not performed. MT, microtubules.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ray Keller, John Wallingford, Daniel Marston, and members of the Harland lab for advice, discussion, and encouragement. We also thank Michael Sohaskey, Saori Haigo, and Kira O’Day for critical reading of the manuscript. The nucleoplasmin b7-1A9 antibody developed by Christine Dreyer was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa. This investigation was supported by National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32HD052374-01 to J.-Y.L. and NIH GM42341 to R.M.H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Baker PC. Fine Structure and Morphogenic Movements in the Gastrula of the Treefrog, Hyla regilla. J Cell Biol. 1965;24:95–116. doi: 10.1083/jcb.24.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett K, Leptin M, Settleman J. The Rho GTPase and a putative RhoGEF mediate a signaling pathway for the cell shape changes in Drosophila gastrulation. Cell. 1997;91:905–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benink HA, Bement WM. Concentric zones of active RhoA and Cdc42 around single cell wounds. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:429–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick AR. Molecular mechanisms of nonmuscle myosin-II regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:26–33. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnside B. Microtubules and microfilaments in newt neuralation. Dev Biol. 1971;26:416–41. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(71)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebstensen RD, Plagemann PG. Cytochalasin B: inhibition of glucose and glucosamine transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:1430–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DL. Organization, nucleation, and acetylation of microtubules in Xenopus laevis oocytes: a study by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Dev Biol. 1991;143:346–62. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90085-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigo SL, Hildebrand JD, Harland RM, Wallingford JB. Shroom induces apical constriction and is required for hingepoint formation during neural tube closure. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2125–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J, Keller R. The behaviour and function of bottle cells during gastrulation of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1988;103:211–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand JD. Shroom regulates epithelial cell shape via the apical positioning of an actomyosin network. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5191–203. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand JD, Soriano P. Shroom, a PDZ domain-containing actin-binding protein, is required for neural tube morphogenesis in mice. Cell. 1999;99:485–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtfreter J. A Study of the Mechanics of Gastrulation, Part I. J Exp Zool. 1943;94:261–318. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson AG, Oster GF, Odell GM, Cheng LY. Neurulation and the cortical tractor model for epithelial folding. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1986;96:19–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R, Danilchik M. Regional expression, pattern and timing of convergence and extension during gastrulation of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1988;103:193–209. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R, Davidson LA, Shook DR. How we are shaped: the biomechanics of gastrulation. Differentiation. 2003;71:171–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.710301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R, Shih J, Domingo C. The patterning and functioning of protrusive activity during convergence and extension of the Xenopus organiser. Dev Suppl. 1992:81–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller RE. An experimental analysis of the role of bottle cells and the deep marginal zone in gastrulation of Xenopus laevis. J Exp Zool. 1981;216:81–101. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402160109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller RE, Danilchik M, Gimlich R, Shih J. The function and mechanism of convergent extension during gastrulation of Xenopus laevis. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985;89(Suppl):185–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly EL, Hardin J. Bottle cells are required for the initiation of primary invagination in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol. 1998;204:235–50. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolsch V, Seher T, Fernandez-Ballester GJ, Serrano L, Leptin M. Control of Drosophila gastrulation by apical localization of adherens junctions and RhoGEF2. Science. 2007;315:384–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1134833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Toth J, Hetenyi C, Malnasi-Csizmadia A, Sellers JR. Mechanism of blebbistatin inhibition of myosin II. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35557–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan KM, Kirschner MW. A microtubule-binding Rho-GEF controls cell morphology during convergent extension of Xenopus laevis. Development. 2005;132:4599–610. doi: 10.1242/dev.02041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MC, Keller R. Microtubule disruption reveals that Spemann’s organizer is subdivided into two domains by the vegetal alignment zone. Development. 1997;124:895–906. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MC, Koehl MA, Wilt F, Keller R. A role for regulated secretion of apical extracellular matrix during epithelial invagination in the sea urchin. Development. 1993;117:1049–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.3.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Scherr H, Wallingford JB. Shroom family proteins regulate gamma-tubulin distribution and microtubule architecture during epithelial cell shape change. Development. 2007;134:1431–1444. doi: 10.1242/dev.02828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Goldstein B. Mechanisms of cell positioning during C. elegans gastrulation. Development. 2003;130:307–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Marston DJ, Walston T, Hardin J, Halberstadt A, Goldstein B. Wnt/Frizzled signaling controls C. elegans gastrulation by activating actomyosin contractility. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1986–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W. Mechanics of Invagination. Anat Rec. 1947;97:139–156. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090970203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BP, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Burridge K. Microtubule depolymerization induces stress fibers, focal adhesions, and DNA synthesis via the GTP-binding protein Rho. Cell Adhes Commun. 1998;5:249–55. doi: 10.3109/15419069809040295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter K, Bucher K, Hauri HP. Microtubule perturbation retards both the direct and the indirect apical pathway but does not affect sorting of plasma membrane proteins in intestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2) Embo J. 1990;9:3163–70. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuji N. Effects of injected inhibitors of microfilament and microtubule function on the gastrulation movement in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 1979;68:140–50. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance J, Munro EM, Priess JR. C. elegans PAR-3 and PAR-6 are required for apicobasal asymmetries associated with cell adhesion and gastrulation. Development. 2003;130:5339–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.00735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin) Garland Publishing; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Odell GM, Oster G, Alberch P, Burnside B. The mechanical basis of morphogenesis. I. Epithelial folding and invagination. Dev Biol. 1981;85:446–62. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry MM, Waddington CH. Ultrastructure of the blastopore cells in the newt. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;15:317–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J, Li N. Microfilament actin remodeling as a potential target for cancer drug development. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4:345–54. doi: 10.2174/1568009043332998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhumbler L. Physikalische Analyse von Lebenserscheinungen der Zelle; III. Arch. f Entw. Mech. 1899;9:63. [Google Scholar]

- Rhumbler L. Zur Mechanik des Gastrulationsvorganges, insbesondere der Invagination. Eine entwicklungsmechanische Studie. Wilhem Roux’ Arch. Entw. Org. 1902;14:401–476. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreitzer G, Musch A. Organization of vesicular trafficking in epithelia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:233–47. doi: 10.1038/nrm1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffini A. Fisiogenia. Francesco Vallardi; Milano: 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh M, Ishikawa T, Matsushima S, Naka M, Hidaka H. Selective inhibition of catalytic activity of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7796–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sater AK, Steinhardt RA, Keller R. Induction of neuronal differentiation by planar signals in Xenopus embryos. Dev Dyn. 1993;197:268–80. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001970405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sive HL, Grainger RM, Harland RM. Early Development of Xenopus laevis: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Solursh M, Revel JP. A scanning electron microscope study of cell shape and cell appendages in the primitive streak region of the rat and chick embryo. Differentiation. 1978;11:185–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1978.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens SJ, Paterson AD, Crampton MS, Shewan AM, Ferguson C, Akhmanova A, Parton RG, Yap AS. Dynamic microtubules regulate the local concentration of E-cadherin at cell-cell contacts. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1801–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF, Cheung A, Limouze J, Chen I, Westwood NJ, Sellers JR, Mitchison TJ. Dissecting temporal and spatial control of cytokinesis with a myosin II Inhibitor. Science. 2003;299:1743–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1081412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeton D, Parks S, Costa M, Wieschaus E. Gastrulation in Drosophila: the formation of the ventral furrow and posterior midgut invaginations. Development. 1991;112:775–89. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.3.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford JB, Harland RM. Neural tube closure requires Dishevelled-dependent convergent extension of the midline. Development. 2002;129:5815–25. doi: 10.1242/dev.00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winklbauer R, Schurfeld M. Vegetal rotation, a new gastrulation movement involved in the internalization of the mesoderm and endoderm in Xenopus. Development. 1999;126:3703–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder M, Hildebrand JD. Shroom4 (Kiaa1202) is an actin-associated protein implicated in cytoskeletal organization. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2007;64:49–63. doi: 10.1002/cm.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young PE, Pesacreta TC, Kiehart DP. Dynamic changes in the distribution of cytoplasmic myosin during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1991;111:1–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie 1: Time-lapse images of bottle cell and subsequent blastopore formation in a Xenopus laevis embryo, vegetal view. The embryo is oriented with dorsal side to the top left (as seen in the first frame). Bottle cells first appear in the dorsal marginal zone, then spread laterally and ventrally to form the blastopore. Frames were taken every two minutes, with total elapsed time of four hours. Playback is at 10 frames per second.

Movie 2: Time-lapse images of bottle cell formation in a marginal zone explant, cultured in DFA. In explants, bottle cells appear to constrict in clusters rather than sequentially spreading from one side of the embryo to the other. Frames were taken every two minutes, with total elapsed time of two hours. Playback is at 10 frames per second.

Movie 3: Time-lapse confocal images of bottle cell formation in an intact embryo expressing membrane-GFP. Constricting cells, with their surface area shrinking, invaginate into the embryo in clusters, while the cells between them are stretched. Frames were taken every two minutes, with total elapsed time of 86 minutes. Playback is at 10 frames per second.