Abstract

Heterologous protein expression can easily overwhelm a cell's capacity to properly fold protein, initiating the unfolded protein response (UPR), and resulting in a loss of protein expression. In the current model of the unfolded protein response, the chaperone BiP modulates the activation of the UPR due to its interactions with the signaling protein Ire1p and newly synthesized proteins. In this research, 4−4−20 scFv variants were generated by rational design to alter BiP binding to newly synthesized scFv proteins or via directed evolution aimed at improved secretion. Interestingly, the predicted BiP binding ability did not correlate significantly with the unfolded protein response. However, pulse-chase analysis of scFv fate revealed that mutants with a decreased ER residence time were more highly secreted, indicating that improved protein folding was more likely the cause for improved secretion. In fact, decreased secretion correlated with increased binding by BiP, as determined by co-immune precipitation studies. This suggests that the algorithm is not useful for in vivo prediction of variants, and that in vivo screens are more effective for finding variants with improved properties.

Introduction

In the pharmaceutical industry, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is ideal for expressing and producing recombinant proteins such as insulin and tissue plasminogen activator (Walsh 2003), due to its quality control system, which enables only correctly folded protein to be secreted from the cells and retains unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Overexpression of heterologous proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can easily overcome the folding capacity of the cell and lead to the unfolded protein response (UPR). During the UPR, multiple cellular functions are upregulated, including secretion and proteolysis (Travers et al. 2000), leading to a low protein yield (Kauffman et al. 2002). Thus, decreasing the UPR and improving protein production remains a challenge in cellular engineering.

In the canonical signaling pathway of the UPR in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (see reviews by Patil and Walter 2001; Sidrauski et al. 1998; Spear and Ng 2001), the chaperone binding protein (BiP) binds to the transmembrane protein Ire1p and stabilizes it in an inactive state during periods of normal cell growth. When the unfolded protein level increases, BiP dissociates from Ire1p in order to bind to unfolded proteins, allowing Ire1p to dimerize and phosphorylate, resulting in the subsequent activation of the unfolded protein response. More recently, BiP's role in this process has been understood to be more minor, as deleting the BiP binding site in Ire1p does not significantly impair UPR activation (Kimata et al. 2004). Our laboratory studies also indicate BiP overexpression had little impact on UPR activation (Raden et al. 2005; Xu et al. 2005). The recent crystal structure of Ire1p indicates a conserved core region of the ER-luminal domain, which was proposed to bind unfolded proteins directly (Credle et al. 2005). Regardless of its role in the UPR, BiP plays multiple functions in protein folding, translocation, and degradation due to its polypeptide binding ability (Fewell et al. 2001). Thus, understanding the relationship between BiP binding to unfolded proteins and its other competing functions will help to reveal the mechanism of UPR regulation.

In this study, we overexpressed the single-chain antibody fragment (scFv) 4−4−20 in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Single-chain antibodies have wide potential application as diagnostic and therapeutic agents (Deng et al. 2003; Holliger and Hudson 2005; Walsh 2003); they are good models for UPR studies as heterologous expression for this protein class is challenging. Our previous studies showed that overexpression of 4−4−20 scFv led to its accumulation in the ER of S. cerevisiae and induced the unfolded protein response (Kauffman et al. 2002), yet overexpressing BiP did not improve 4−4−20 expression (Xu et al. 2005). Here, we wanted to directly examine the interactions between BiP and 4−4−20 scFv to see how those interactions effected 4−4−20 secretion and the UPR.

In previous studies, mutations to the BiP-substrate binding domain led to a constitutive UPR even in the absence of extrinsic stress (protein unfolding activated by chemical treatment with dithiothreitol) (Kimata et al. 2003). However, the effects of changing the BiP binding sites in the recombinant protein on the UPR as well as other cellular activities is still unknown. In this research, we used 4−4−20 scFv variants to elucidate this relationship.

Materials and Methods

Strains and plasmids

Yeast strain BJ5464 (MATα ura3−52 trp1 leu2Δ1 hisΔ200 pep4::HIS3 prb1Δ1.6R can1 GAL) was used in all the experiments except yeast surface display, where yeast strain EBY100 (Invitrogen) was used. EBY100 contains the vector pIU211, which integrated into the AGA1 locus of yeast genome of strain BJ5465 (Boder et al, 1997, USpatent 6423538). pIU211 contains the AGA1 gene regulated by the GAL promoter and a URA3 selectable marker.

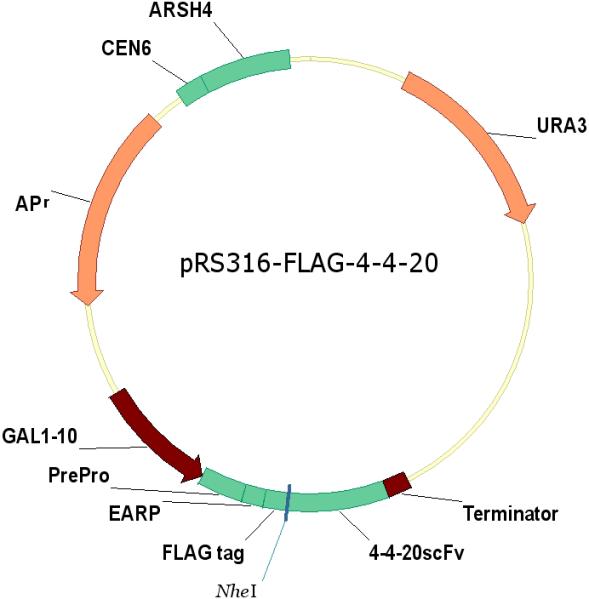

The plasmids pRS316-FLAG-F216A, pRS316-FLAG-F259A, pRS316-FLAG-W225A, and pRS316-FLAG-V279D were created by site-directed mutagenesis of the 4−4−20 scFv gene in the plasmid pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 following the protocol of QuikChange® II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). The pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 plasmid consists of a GAL1−10 promoter, a synthetic pre-pro sequence, an EARP peptide spacer, an N-terminal FLAG epitope tag, and the 4−4−20 coding region, followed by an α-terminator, as shown in Figure 2. The mutations in pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 were verified by DNA sequencing and the resulting plasmids carrying the mutated scFv genes were transformed into BJ5464 with the UPR stress sensor pRS314-UPRE-GFP (Xu et al. 2005), which includes the green fluorescent gene GFP driven by the unfolded protein response element (UPRE). The cells were selected on plates with selective media SD-2×SCAA (SD) (Wittrup and Benig 1994) lacking the appropriate amino acids.

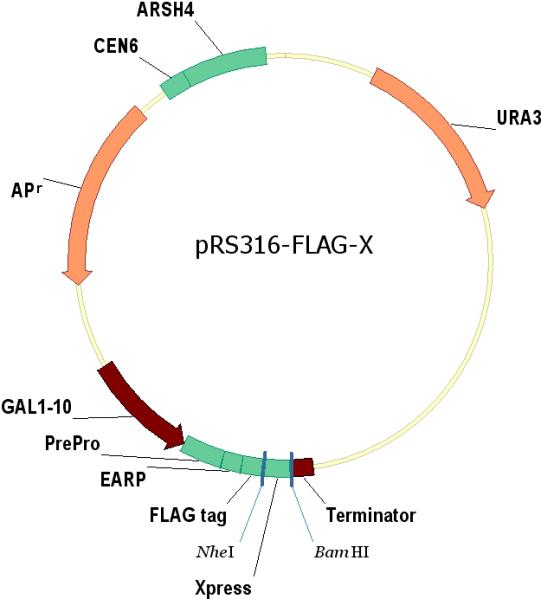

Figure 2.

Schematic of expression constructs pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 and pRS316-FLAG-X. The expression constructs containing F216A, F259A, W225A, and V279D variants were made by site-directed mutagenesis in the pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 plasmid. To construct pRS316-FLAG-X, a BamHI restriction site was created at the end of the scFv 4−4−20 sequence in the pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 plasmid by site-directed mutagenesis. Then the Xpress region cut from pYD1 (Invitrogen) replaced the 4−4−20scFv gene between NheI and BamHI. The expression construct containing the P64S variant was made by inserting the P64S gene in the Xpress region of the pRS316-FLAG-X plasmid.

pYD1 (Invitrogen) was the vector used for yeast surface expression. pYD1-scFv was constructed by amplifying the 4−4−20 scFv gene through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the plasmid pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20, and introduced into the pYD1 vector after digestion with NheI and BamHI restriction enzymes. The two primers used in the reaction were forward primer 5’-TACAAGGACGACGATGACAAG-3’, and reverse primer 5’-CGGGATCCGGAGACGGTGACTGAGGTTCC-3’.

The 4−4−20 mutant library was constructed as follows: pYD1-scFv was used as the template in the PCR reaction following the protocol of Colby et al. (2004) with two nucleotide analogues, 8-oxo-2’ deoxyguanosine-5’-triphosphate and 2’-deoxy-p-nucleoside-5’-triphophate (8-oxo-dGTP and dPTP respectively, TriLink Biotech), which creates both transition and transversion mutations. Two primers having > 48 bp homology with pYD1-scFv were used: forward primer 5’-CTAGCAAAGGCAGCCCCATAAACACACAGTATGTTTTTAAGCTTCTGCAG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-CTCGAGCGGCCGCCACTGTGCTGGATATCTGCAGAATTCCACCACACT-3’. The mutant PCR product and the backbone pYD1 (from pYD1-scFv) digested with NheI and BamHI were concentrated via Paint (Novagen) after gel purification and transformed into EBY100 via homologous recombination to construct a mutant library. The library size was ∼4×107. After sorting using Cytomation MoFlo (Cytomation, Inc., Fort Collins, CO), the 4−4−20 variants of interest, which resided in the backbone of pYD1, were rescued from the cells using the Y-DER Yeast DNA Extraction Reagent Kit (Pierce).

In order to examine the secretion of the 4−4−20 variants, the 4−4−20 mutant genes were subcloned into the secretion vector pRS316-FLAG-X, as shown in Figure 2. This vector was constructed from the plasmids pYD1 and pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20. Initially, the first two stop codons of pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 were changed to a BamHI site using site-directed mutagenesis (Strategene), leaving the last two stop codons intact and functional. This plasmid was then digested with NheI and BamHI to remove the wild type 4−4−20 scFv gene and replace it with a fragment containing the Xpress epitope (∼66 bp) cut from pYD1 using the same restriction enzymes to obtain pRS316-FLAG-X. Next, the 4−4−20 scFv mutant fragment cut from the expression vector using NheI and BamHI restriction enzymes was ligated into pRS316-FLAG-X backbone to construct the plasmid pRS316-FLAG-mutant, which was then transformed into BJ5464 with the UPR stress sensor pRS314-UPRE-GFP. The cells were selected on SD-2×SCAA plates (Wittrup and Benig 1994) lacking appropriate amino acids for further study of the unfolded protein response and scFv secretion.

Yeast cell culture

For yeast surface display, the 4−4−20 mutant library was inoculated in SD-2×SCAA liquid medium lacking appropriate amino acids and grown at 30°C in a water bath shaker. The overnight culture was diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 and grown to an OD600 of 1.0. scFv expression was induced by transfer to galactose via SG-2×SCAA liquid medium at an OD600 of 1.0. After 51 hours growth in SG-2×SCAA media at 30°C, 20 OD-ml cells were harvested for further labeling and sorting. The sorted cells were grown similarly and scFv expression was induced by growth in SG-2×SCAA liquid medium. After 51 hours, 1 OD-ml cells were collected for the detection of surface scFv levels by Western blotting.

In order to examine the unfolded protein response during the expression of different mutants, yeast strains carrying different scFv mutant gene and the UPR stress sensor pRS314-UPRE-GFP were grown in semi-continuous culture in SD-2×SCAA media lacking uracil and tryptophan at 30°C. During the induction phase, pre-warmed SG media was added approximately every 2 hours, maintaining the OD600 of the culture between 0.2 and 0.3. At each time point, 1 OD-ml of cells was collected by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes for further fluorescence measurement and Western blot analysis.

In order to examine the scFv secretion of different variants, the yeast strains carrying the scFv mutant genes were grown in batch with SD-2×SCAA media lacking appropriate amino acids at 30°C. scFv expression was induced by growth in SG media, buffered to pH 6.0 with 50 mM sodium phosphate, and supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml BSA to improve scFv recovery from the supernatant. After 51 hours growth at 30°C, the secreted scFv protein from 1.8 ml supernatant was precipitated with 7.2 ml saturated ammonium sulfate (Xu et al. 2005) and resuspended with 30 μl resuspension buffer (3% SDS, 100 mM Tris base, pH 11, 3 mM DTT), boiled at 95 °C, and stored at −80 °C for future SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Cell labeling and cell sorting

For detecting scFv expressed on the surface, 2 OD-ml cells were washed with PBS /0.1% BSA and then labeled with 2 μg anti-V5 primary antibody (Invitrogen) in 100 μl PBS / 0.1% BSA at 4°C for 1 hour. After washing with PBS /0.1% BSA, the cells were labeled with 2 μl anti-mouse Ig phycoerythrin secondary antibody (Abcam Inc.) at 4°C for another 1 hour. About ∼0.2 % of the cells with the highest phycoerythrin (PE) fluorescence, 2.6×108 cells (∼ 6× library), were screened using a Cytomation MoFlo (Cytomation, Inc., Fort Collins, CO; The Wistar Institute, University of Pennsylvania). 597,000 cells with the highest PE fluorescence were collected in 5 ml SD-2×SCAA liquid media lacking uracil and tryptophan, which was adjusted to pH 4.5 with sodium citrate (14.7 g/L) and citric acid monohydrate (4.3 g/L), and including kanamycin (30 μg/ml) and ampicillin (50 μg/ml). ∼1000 cells were spread onto SD-2×SCAA media plates. 26 individual colonies were selected in order to examine the surface display level by Western blotting; two of them showed some improvement in the surface display levels and were further cloned into the secretion vector pRS316-FLAG-X for detailed study. One mutant, P64S, was found to have a higher secretion level than the wild type. Further rounds of selection on the library did not yield improvement, as a small fraction of cells carrying the parental plasmid pYD1, which came from DNA contamination during library construction, became highly enriched.

BiP scoring algorithm

A scoring program (Blond-Elguindi et al. 1993) was used to predict BiP binding sites in the 4−4−20 scFv sequence. The BiP scoring program uses an algorithm that scores the amino acids in the protein by predicting the binding probability of every heptapeptide. For each seven-residue sequence, the program computes a score

where s(i,p) is a parameter related to the probability of finding a residue of type p (1 of the 20 amino acids) at position i in the seven residue sequence beginning at position n in the polypeptide sequence. The values of s(i,p) were determined from the analysis of the probability of BiP binding via bacteriophage display of a library of peptides (Blond-Elguindi et al. 1993).

Fluorescence measurement of GFP

The unfolded protein response was measured using GFP fluorescence as a reporter from the UPRE-GFP plasmid (Xu et al. 2005). 1 OD-ml cells obtained from semi-continuous culture were resuspended with 1 ml PBS buffer (8 g/L NaCl, 1.44 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.24 g/L KH2PO4, 0.2 g/L KCl). GFP fluorescence was measured on an F-4500 Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Hitachi) using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 510 nm. After the measurement, the cells were centrifuged to remove the PBS buffer and lysed as described by Robinson et al. (1996) The cell lysate was stored at −80°C for future Western blot analysis of scFv levels.

Pulse-chase and immunoprecipitation

Yeast strains were grown in batch with SD-2×SCAA media lacking appropriate amino acids at 30°C. scFv expression was induced by transfer to SG-2×SCAA liquid minimal media lacking appropriate amino acids at 30°C. During the induction phase, prewarmed SG media was added approximately every 2 hours, maintaining the OD600 of the culture between 0.2 and 0.3. After 16 hours growth, the cells were transferred to prewarmed SG media with excess amino acids lacking methionine for 1 hour. Then the cells were labeled with 240 μCi/OD-ml Tran35S-label (MP Biomedicals, Inc.) for 10 minutes and chased by the addition of SG media plus 1 mg/ml methionine for 1 hour as described previously (Xu et al. 2005). 1 OD-ml of radiolabelled cells was collected at each time point and lysed with lysis buffer (2% SDS, 90 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 30 mM DTT and 0.4 mg/ml Pefabloc; Sigma-Aldrich).

The radiolabeled protein was immunoprecipitated as described previously (Xu et al. 2005). Briefly, the cell lysate was incubated with 4 μl of mouse anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) per OD-ml for 1 hour and 50 μl of Protein A (Repligen) for another hour at 4°C. The sample pellets were boiled in 100 μl 2×SDS loading buffer for 5 minutes. 30 μl samples were loaded onto 11% SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, the gel was soaked in Amplify (Amersham) for 30 min, and dried. The dried gel was subsequently exposed and scanned on a Typhoon 9400 and quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

In order to examine the association of BiP with scFv variants, yeast strains were grown in batch with SD-2×SCAA media lacking appropriate amino acids at 30°C. The expression of scFv variants was induced by switching to SG-2×SCAA liquid minimal media lacking appropriate amino acids at 30°C. After ∼20 hours induction in the batch culture, 10 OD-ml cells were collected. The cells were lysed by a nondenaturing protocol, as described by Kohno and colleagues (Okamura et al. 2000). The recovered lysates were incubated with 4 μl of mouse anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody for 1 hour followed by 50 μl of Protein A (Repligen) for another 1 hour at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were solubilized by boiling with 100 μl 2×SDS loading buffer for 5 minutes and detected by Western blotting. Control cells lacking the scFv expression plasmid showed negligible levels of BiP in the immunoprecipitate; thus, there was no nonspecific binding of the FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody to BiP.

Immunoblotting

The intracellular scFv was obtained by lysing the cells with lysis buffer (2% SDS, 90 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 30 mM DTT and 0.4 mg/ml Pefabloc; Sigma-Aldrich), and boiled at 95°C for 10 minutes (Xu et al. 2005). The surface scFv was rescued by incubating the cells with 50 μl protein releasing buffer (100 mM Tris base, pH 11, 3 mM DTT) at 4°C for 2 hours. The intracellular, surface, and secreted scFv protein in samples of cell lysates and supernatants was detected by 11% SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting as described by Robinson et al. (1996) using the mouse anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:2,000 dilution. Sheep anti-mouse HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham) was used at 1:2,000 dilution. The antibody-antigen complex was visualized with ECL plus Western blotting detection reagents system (Amersham). Images were scanned with a Typhoon 9400 and quantified with ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

Results

Construction /selection of 4−4−20 mutants and analysis of BiP binding probability using a BiP scoring algorithm

The chaperone BiP has multiple functions in protein folding, translocation and ER Associated Degradation (ERAD) due to its innate unfolded protein binding ability (Fewell et al. 2001). In the unfolded protein response, the binding of BiP to unfolded proteins leads to the dissociation of BiP from Ire1p, and the subsequent activation of the UPR (see reviews by Patil and Walter 2001; Sidrauski et al. 1998; Spear and Ng 2001). In order to better understand the effect of BiP binding to heterologous single-chain antibody 4−4−20 (scFv) protein on antibody production and UPR regulation, we examined the effect of modifying BiP-antibody binding.

Two methods were used to generate 4−4−20 scFv mutants: rational design and random mutagenesis. Unfolded proteins with lower BiP binding ability potentially free BiP and enable it to bind and stabilize the UPR stress sensor protein Ire1p. Based on our earlier studies, overexpression of BiP led to increased scFv-BiP binding levels (Xu et al. 2005). Therefore, a BiP algorithm was used to identify sites that would reduce BiP binding to scFv (Blond-Elguindi et al. 1993; Davis et al. 1999; Gething et al. 1995; Knarr et al. 1995; Knarr et al. 1999; Rudiger et al. 1997; Sorgjerd et al. 2006; Takenaka et al. 1995).

The algorithm scores each amino acid in the sequence with a moving window of seven amino acids. An individual score is then assigned to each amino acid depending on its position in the heptapeptide, and the sum of the seven scores provides a measure of the probability that a given heptapeptide might bind to BiP. Peptides with scores ranging from +5 to +10 have a probability of 50% for binding to BiP, increasing to 80% for peptides with scores ≥10. If the BiP score is ≤ 0, the probability of binding to BiP is close to zero (Knarr et al. 1995).

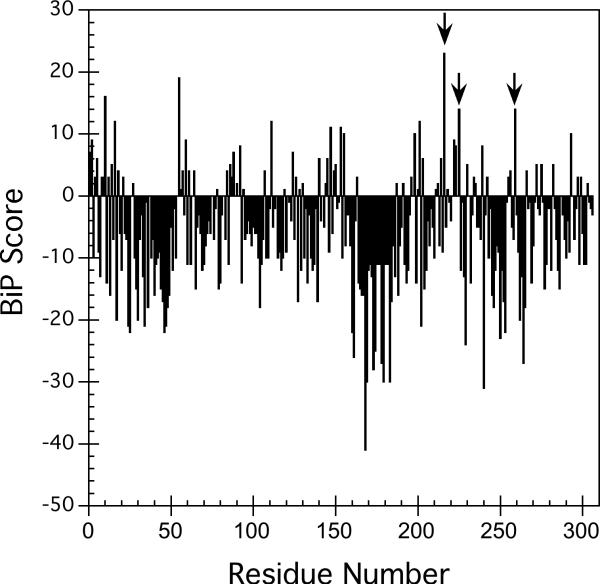

Figure 1A shows the results of the BiP scoring for 4−4−20 scFv. Only a small fraction (9%) of the heptapeptides have BiP scores over 6, which was consistent with the BiP score of the antibody 3D6 Fd fragment and the MAK33 heavy chain (Fd + Fc) (Knarr et al. 1995). Of the potential BiP sites, three (F216, W225 and F259) showing a very high BiP score (≥ 10) were chosen for site-directed mutagenesis (Table 1). A relatively conservative change to alanine was chosen at these sites, resulting in a decrease in the BiP score from 23 to 11, from 14 to 4, and from 14 to 2 for F216, W225, and F259 respectively, as shown in Table 1. Although other mutations were considered, we felt that this change should result in a behavior change if the algorithm was effective in predicting BiP binding. A more conservative change, for example to phenylalanine, did not sufficiently change the BiP score, so was not considered for this reason.

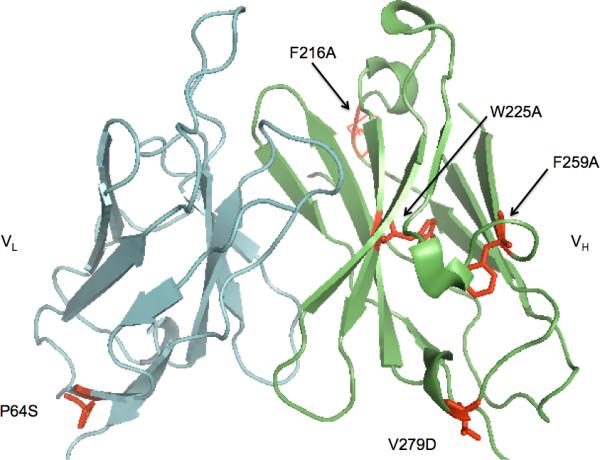

Figure 1.

A. BiP score of single-chain antibody 4−4−20. The BiP score at each site in the sequence of 4−4−20 scFv was calculated by the BiP scoring algorithm, which scores the amino acids in the proteins by measuring the binding probability of every heptapeptide as described in the Materials and Methods. The mutation sites with the arrows from left to right were F216, W225, and F259 respectively. B. A representation of the structure of 4−4−20 scFv based on the crystal structure of the Fab fragment (PDB entry 1FLR, Whitlow et al. 1995) where the positions of the mutants of F216A, F259A, V279D, W225A and P64S are highlighted as space filling side chains.

Table 1.

The 4−4−20 mutants used in this study. F216A, W225A, F259A, V279D were made by site-directed mutagenesis; P64S was selected from the screening as described in the Materials and Methods. The BiP scores before and after mutation were calculated by the BiP scoring algorithm as described in the Materials and Methods. The expected changes in the BiP binding affinity are shown by the following symbols: decreased (↓) or no change (N/C).

| scFv mutants | Source | BiP score before mutation | BiP score after mutation | BiP binding affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F216A | Site-directed mutagenesis | 23 | 11 | ↓ |

| W225A | Site-directed mutagenesis | 14 | 4 | ↓ |

| F259A | Site-directed mutagenesis | 14 | 2 | ↓ |

| V279D | Site-directed mutagenesis, reported by Nieba et al, 1997 | −11 | −12 | N/C |

| P64S | Screening | 4 | 2 | N/C |

A second approach to modifying BiP-scFv interactions was using random mutagenesis via error-prone polymerase chain reaction. As the UPR activated by the expression of 4−4−20 scFv was decreased when protein secretion was improved (Xu et al. 2005), we expected that those 4−4−20 variants that the cell was able to secrete would possibly fold better and have a lower UPR during their expression. Thus, we hoped that further analysis of the BiP binding ability of variants could give us some insight of the relationship between BiP binding and UPR activation and protein secretion.

Here we employed yeast surface display to select scFv variants with the highest secretion levels. Yeast surface display has been used as a discovery and characterization platform of antibody fragments (Feldhaus and Siegel 2004). As a high secreted protein level has corresponded very well with a high surface display level (Shusta et al. 2000), the screening of high secretion mutants by selecting high surface displayed levels was investigated. After screening a population of 260 million cells labeled with a fluorescent antibody (described in Materials and Methods), the top 0.2% of cells with higher fluorescence (higher surface scFv levels) was selected. Of 26 clones obtained from this screening, one mutant (P64S) with higher secretion than the wild type was identified as described in the Materials and Methods. Using the BiP scoring program, the BiP score was calculated for P64 (Table 1). The BiP score at this position was 4 before and 2 after the mutagenesis, respectively, which indicates that the heptapeptide surrounding this site is not a likely BiP binding site.

The V279D variant was also used in our study as it was reported to be more soluble (under the name H84D) in E. coli (Nieba et al. 1997). The BiP scoring analysis showed that the BiP score at V279 was −11 before and −12 after the mutation, indicating a low predicted BiP binding.

Therefore, among the 4−4−20 scFv variants we examined, three (F216A, W225A, F259A) were chosen at possible BiP binding sites, and the BiP binding was designed to decrease via the mutations; two variants (V279D, P64S) were predicted to have low BiP binding, and their BiP binding ability was likely unaffected by the mutations. Although for all five mutants the single mutation changed the BiP scores of several heptapeptide regions upstream of where the mutation was made, the BiP scores at those regions were low (no greater than 6) after mutation (data not shown), indicating the probability of altering the BiP binding at those sites was low. Among the five residues shown in Figure 1B, F216A, F259A, V279D, W225A are in the heavy chain, P64S in the light chain; F216A, F259A, V279D, P64S are on the surface, and W225A is buried inside the protein; V279D and P64S are on the interface of variable and constant domains.

Difference in the secretion of 4−4−20 scFv variants

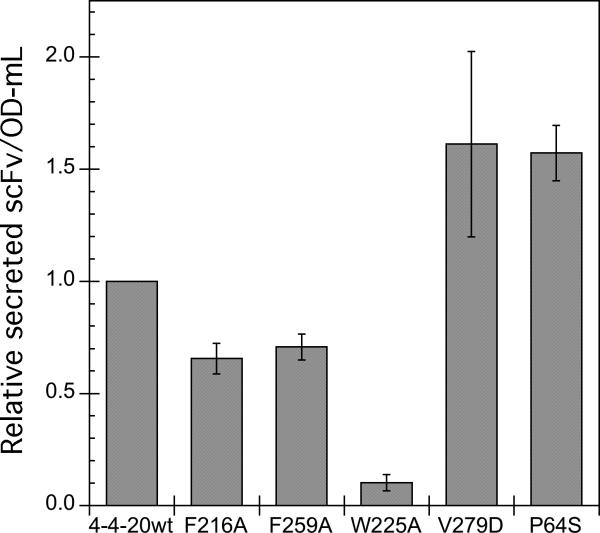

In order to examine the secretion of 4−4−20 scFv variants, the plasmids pRS316-FLAG-F216A, pRS316-FLAG-F259A, pRS316-FLAG-W225A, pRS316-FLAG-V279D, and pRS316-FLAG-P64S were constructed to enable secretion of variant proteins, as shown in Figure 2, and the plasmids were transformed into BJ5464. Cells were then grown in SD-2×SCAA liquid media lacking the appropriate amino acids, and scFv protein expression was induced by growth on galactose-containing (SG-2×SCAA) media. After 51 hours, the secreted scFv level was examined by Western blotting, and the results are shown in Figure 3. The F216A, F259A and W225A variants had lower secretion than the wild type, and in particular, the secretion of the W225A variant was barely detectable. However, the V279D and P64S variants had higher secretion levels than the wild type.

Figure 3.

The secretion of 4−4−20 scFv mutants. BJ5464 strains transformed with a plasmid carrying the F216A, F259A, W225A, V279D, or P64S mutant genes, or the wild type 4−4−20 gene were grown in SG-2×SCAA-Ura-Trp for 51 hours to induce the expression of scFv protein. The secreted scFv was precipitated and detected by Western blotting as described in the Materials and Methods. The error bars represent the standard deviation from the average of at least two experiments.

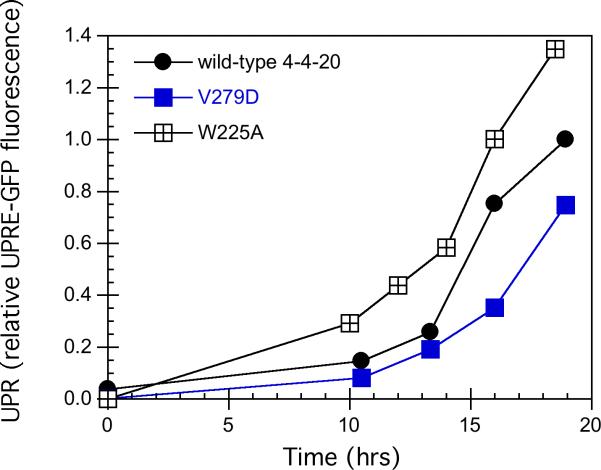

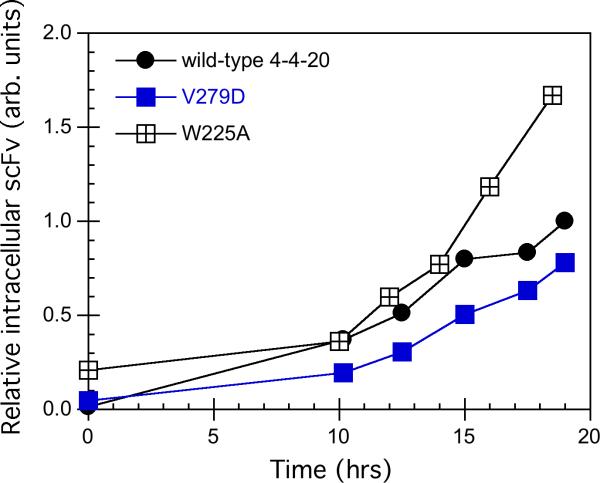

4−4−20 scFv variants designed with algorithm for low BiP binding did not lead to a decreased unfolded protein response

In order to see how BiP binding ability affected the unfolded protein response, W225A and V279D were chosen for further study because of the large difference in secretion. W225A showed an extremely low secretion level, and a predicted decrease in its binding to BiP; V279D showed a higher secretion than the wild type, and no predicted effect on BiP binding. These two variants and the wild type were each transformed into BJ5464, along with the stress sensor pRS314-UPRE-GFP. The unfolded protein response (UPR) activated by expressing each variant and the wild type is shown in Figure 4A. Control cells expressing pRS314-UPRE-GFP, but lacking the scFv expression vector, showed low fluorescence values, as reported previously (Xu et al, 2005). Following induction, the GFP fluorescence in the three strains increased over time, but the W225A variant has a higher UPR than the wild type, indicated by the highest fluorescence. Since the mutant was designed with lower BiP binding, it was expected to have a lower unfolded protein response. The increase in the UPR of W225A was consistent with the lower secretion of W225A (Figure 3) and a higher intracellular scFv level (Figure 4B). In contrast to W225A, the UPR of the V279D variant was lower, consistent with its higher secretion (Figure 3) and lower intracellular scFv level (Figure 4B). A student's unpaired t-test analysis (GraphPad software) was applied to the data in Figure 3. For the relative fluorescence at 18h, the p value is less than 0.04 for wt, W225A and V279D (determined by comparing wt to each variant, with the null hypothesis being equal values). For the relative scFv level at 18h, the p value is less than 0.02 for wt, W225A and V279D (determined by comparing wt to each variant, with the null hypothesis being equal values). Therefore their difference is significant. These results indicate that the predicted decreased BiP binding ability of W225A did not decrease the unfolded protein response, and actually, more W225A was accumulated in the cells, leading to a higher UPR. For V279D, less V279D accumulated inside the cells than the wild type, and the unfolded protein response was decreased.

Figure 4.

The unfolded protein response during expression of 4−4−20 variants. BJ5464 transformed with the plasmid pRS314-UPRE-GFP as well as the plasmids carrying the V279D, W225A and the wild type scFv genes were grown semi-continuously in SG-2×SCAA-Ura-Trp as described in the Material and Methods. 1 OD-ml cells were taken to measure the GFP fluorescence and the intracellular scFv level by Western blotting followed by the quantification using ImageQuant Software. (A) The GFP fluorescence time course during the expression of 4−4−20 scFv variants. Wild type (•), V279D (■) and W225A (▲). (B) The intracellular scFv level time course during the expression of 4−4−20 scFv variants. Wild type (○), V279D (□) and W225A (Δ). The figures shown are representative of at least three independent experiments using different transformants for each strain. Error in fluorescent measurements was typically less than 5% and for Western blots less than 10%.

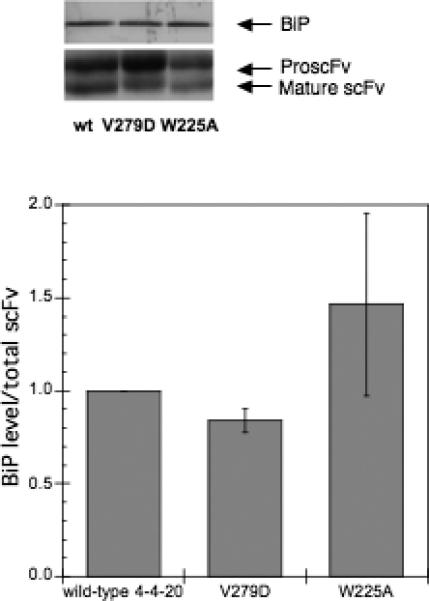

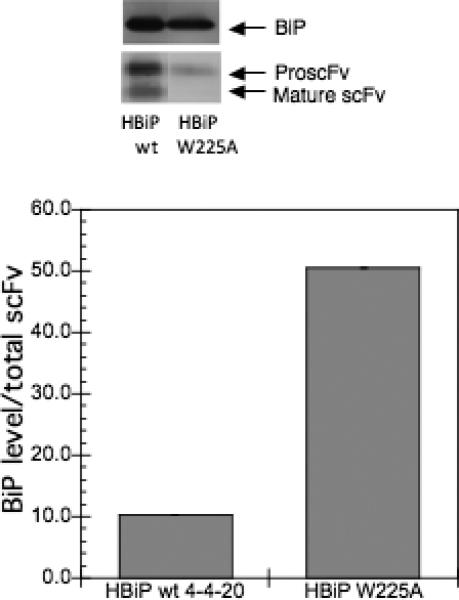

More BiP associated with the low-secretion W225A variant

Since the BiP scoring program predicted a decreased BiP binding to the W225A variant, we wanted to examine the level of BiP associated with this variant as well as V279D in vivo. The strains transformed with pRS316-FLAG-W225A, pRS316-FLAG-V279D, and pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 were grown in SG-2×SCAA lacking the appropriate amino acids for ∼20 hours. The relative level of BiP associated with the total intracellular scFv was examined using immunoprecipitation followed by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 5, the level of BiP associated with V279D is lower than the wild type, but the level of BiP associated with W225A is higher than the wild type, in contrast with predictions from the algorithm. When W225A was expressed in the strain which overexpressed BiP, more BiP bound to W225A, as shown in Figure 5B. The higher BiP level associated with W225A indicates that more BiP binds W225A, possibly preventing its aggregation. In cells lacking scFv expression, nonspecific antibody binding to BiP was negligible (data not shown). We note that the levels of pro-scFv for the 279A variant were significant, but this result was not unexpected given the fact that we accumulate protein within the culture after 20 hours, and that the mature scFv protein should be secreted readily. In addition, the lower total levels of W225A may reflect increased degradation of intracellularly retained proteins.

Figure 5.

BiP binding to the 4−4−20 variants. A) The strain BJ5464 was transformed with the V279D, W225A and the wild type scFv plasmids and grown in SG media lacking the appropriate amino acids for ∼20 hours to induce the scFv expression. B) Similarly, HBiP, a strain overexpressing BiP, was transformed with plasmids carrying the W225A and the wild type scFv genes, and grown for ∼20 hours. 10 OD-ml cells were collected and lyzed using non-denaturing methods. The complex of scFv and BiP in the lysate was co-immunoprecipitated using anti-M2 antibody and the precipitated scFv and BiP were analyzed using Western blotting and quantified by ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). The BiP level was normalized to the total scFv level in the immunoprecipitated proteins. The error bar represents the standard deviation from the average of duplicate samples.

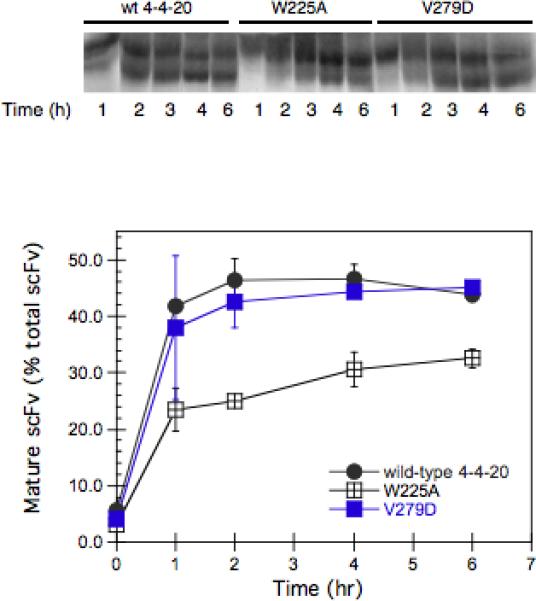

The conversion from the proscFv to the mature scFv was reduced for the W225A variant

Pulse-chase experiments were carried out in order to examine the conversion of the ER form of the scFv (pro-scFv) into the mature scFv, whose pro sequence is removed in the Golgi by the Golgi-resident Kex2 protease (Shusta et al. 1998). Strains were grown semi-continuously at an OD of ∼0.2−0.3, as described in Materials and Methods, for 16 hours in SG-SCAA prior to pulse-labeling, in order to compare behavior to the UPR experiment shown in Figure 4. The strains transformed with pRS316-FLAG-V279D, pRS316-FLAG-W225A, and pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 were radiolabeled with Tran35S-label methionine for 10 minutes, and unlabeled media was then added in excess and the fate of the radiolabeled protein was tracked for 6 hours. The results shown in Figure 6A indicate that during the 6-hr “chase”, the mature scFv percentage reached a plateau for the wild type, but still increased for the V279D variant, which was somewhat higher than the wild type at the end of the chase period. In contrast, the conversion from the proscFv into the mature scFv for the W225A variant was reduced. This indicates that W225A was not able to exit from ER efficiently, possibly due to a folding problem associated with W225A. These results are consistent with the UPR data observed in Figure 4.

Figure 6.

The conversion from proscFv to the mature scFv for different 4−4−20 scFv variants. A. The strain BJ5464 transformed with plasmids carrying the V279D, W225A and the wild type scFv genes was grown in SG media lacking the appropriate amino acids for ∼16 hours to induce the expression of scFv. Then after growth in SG media lacking methionine for 1 hour, the cells were radiolabeled for 10 minutes with 35S-methionine and before amino acids were added in excess as described in the Materials and Methods. Samples were collected at various times during a 6-hour chase, and the radiolabeled scFv was immunoprecipitated and detected by autoradiography. B. The percentage of mature scFv in the total scFv for the different 4−4−20 scFv variants as a function of time. The radiolabeled scFv was quantified using ImageQuant software. Wild type (•), V279D (■) and W225A (▲).

Discussion

In this research, we used both rational design via site-directed mutagenesis and the screening of a combinatorial mutant library to study the relationship between the unfolded protein response, BiP binding, protein folding, and protein secretion. Among the variants we created, F216A, F259A, and W225A were predicted to have a decreased BiP binding ability using the BiP scoring algorithm (Blond-Elguindi et al. 1993). However, the immunoprecipitation experiments showed more BiP associated with W225A, indicating W225A did not fold correctly, possibly leading to the exposure of other BiP binding sites and enabling more BiP to bind to it. This indicates the BiP scoring algorithm ultimately may not be a useful prediction algorithm for design of protein variants. In this case, a higher unfolded protein response was observed in W225A, and the higher UPR was consistent with the lower secretion of this variant. Using pulse-chase experiments, we observed that W225A was slow to convert from the proscFv to the mature scFv.

From the flow cytometry screening via yeast surface display (Feldhaus and Siegel 2004), a variant (P64S) was identified with a high secretion level, similar to that observed for the V279D variant. The latter was reported previously to be more soluble than the wild-type protein in E. coli (Nieba et al. 1997). The P64S and V279D variants share similar features: the mutations were both from hydrophobic to hydrophilic amino acids at the former interface of variable and constant domains. Interestingly, residue P64 was one of 9 hydrophobic residue potential candidates for replacement by the Pluckthun group, which was named L12 (Pro) in their paper (Nieba et al. 1997). Through the yeast surface display screening, the P64S site was identified by our group in a random selection. However, the selection of this mutant was not so surprising if one considers that serine is highly conserved in the antibody backbone in different species, and the probability of serine at residue 64 is 84% for human VL κ, 50% for murine VL κ, 99% for human VL λ (Nieba et al. 1997). Therefore, it seems that natural evolution may have driven a favorable choice of serine at residue 64, possibly making it more soluble, which was consistent with our screening goals. Using the BiP scoring algorithm, it was found that the heptapeptide regions around residues 64 and 279 were not likely BiP binding sites, either before or after mutagenesis.

Although there was no anticipated change in BiP binding from the algorithm predictions, the unfolded protein response of V279D was decreased. Using immunoprecipitation, we found that BiP protein levels associated with the unfolded protein scFv of V279D were decreased somewhat, possibly due to the improvement in the folding of this protein variant.

The observed decrease in scFv secretion, the increase in scFv retention, and the increase in the unfolded protein response using W225A (or the opposite effects for V279D) in this study are consistent with the observations of Shusta and colleagues for temperature effects on protein secretion (Huang, et al., 2008). In their study, the lowest unfolded protein response was correlated well with the highest secretion of 4−4−20 scFv at 20°C, by comparison to higher temperatures.

Here, the retention of W225A inside the cells was tracked further using pulse-chase experiments. We observed that the conversion of W225A to the mature form was much lower than the wild type and V279D variants. The lower conversion of W225A was correlated to lower secretion of this protein. We also noticed that, although small, the conversion of W225A continued through the end of the chase time, whereas the conversion of the wild type reached a plateau in around one hour. As the stress relief machinery was already activated in the cells (UPR activated by 16 hours when pulse-chase was started), it is likely that this had an impact on all three protein variants, modulating the conversion of pro-scFv to the mature form. Since W225A showed a stronger association with BiP (Figure 5), this might explain the differences observed. However, the ER processing of W225A facilitated by the unfolded protein response seemed to be limited, as the intracellular level of W225A remained high during the time frame of our experiments (Figure 4).

Taking all the data together, our results indicate that the BiP binding algorithm is of limited predictive utility for in vivo BiP binding or protein secretion behavior for the scFv system. In this case, screening for secretion does appear to correlate with improved protein folding and a decreased unfolded protein response. For antibodies, disrupting the hydrophobic patches at the interface of variable and constant domains may improve antibody folding, reducing the unfolded protein response and improving antibody secretion. Alternatively, for non-antibody products, developing a screen for improved folding properties is likely to be more fruitful for improving yields.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. K. Dane Wittrup (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for providing the pRS316-FLAG-4−4−20 plasmid and thank Dr. J. Brodsky (University of Pittsburgh) for providing anti-BiP antibody. We thank Dr. David Raden, Dr. Francis J. Doyle, III, and Scott Hildebrandt for helpful discussions. This research was supported by NIH GM 65507 and NIH GM 075297.

References

- Blond-Elguindi S, Cwirla SE, Dower WJ, Lipshutz RJ, Sprang SR, Sambrook JF, Gething MJ. Affinity panning of a library of peptides displayed on bacteriophages reveals the binding specificity of BiP. Cell. 1993;75(4):717–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby DW, Kellogg BA, Graff CP, Yeung YA, Swers JS, Wittrup KD. Engineering antibody affinity by yeast surface display. Methods Enzymol. 2004;388:348–58. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)88027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Credle JJ, Finer-Moore JS, Papa FR, Stroud RM, Walter P. On the mechanism of sensing unfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(52):18773–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509487102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DP, Khurana R, Meredith S, Stevens FJ, Argon Y. Mapping the major interaction between binding protein and Ig light chains to sites within the variable domain. J Immunol. 1999;163(7):3842–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng XK, Nesbit LA, Morrow KJ., Jr. Recombinant single-chain variable fragment antibodies directed against Clostridium difficile toxin B produced by use of an optimized phage display system. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10(4):587–95. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.4.587-595.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15(6):553–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldhaus MJ, Siegel RW. Yeast display of antibody fragments: a discovery and characterization platform. J Immunol Methods. 2004;290(1−2):69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fewell SW, Travers KJ, Weissman JS, Brodsky JL. The action of molecular chaperones in the early secretory pathway. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:149–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething MJ, Blond-Elguindi S, Buchner J, Fourie A, Knarr G, Modrow S, Nanu L, Segal M, Sambrook J. Binding sites for Hsp70 molecular chaperones in natural proteins. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1995;60:417–28. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1995.060.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Holliger P, Hudson PJ. Engineered antibody fragments and the rise of single domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(9):1126–36. doi: 10.1038/nbt1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Gore PR, Shusta EV. Increasing yeast secretion of heterologous proteins by regulating expression rates and post-secretory loss. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;101:1264–75. doi: 10.1002/bit.22019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman KJ, Pridgen EM, Doyle FJ, 3rd, Dhurjati PS, Robinson AS. Decreased protein expression and intermittent recoveries in BiP levels result from cellular stress during heterologous protein expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Prog. 2002;18(5):942–50. doi: 10.1021/bp025518g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Kimata YI, Shimizu Y, Abe H, Farcasanu IC, Takeuchi M, Rose MD, Kohno K. Genetic evidence for a role of BiP/Kar2 that regulates Ire1 in response to accumulation of unfolded proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(6):2559–69. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Oikawa D, Shimizu Y, Ishiwata-Kimata Y, Kohno K. A role for BiP as an adjustor for the endoplasmic reticulum stress-sensing protein Ire1. J Cell Biol. 2004;167(3):445–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knarr G, Gething MJ, Modrow S, Buchner J. BiP binding sequences in antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(46):27589–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knarr G, Modrow S, Todd A, Gething MJ, Buchner J. BiP-binding sequences in HIV gp160. Implications for the binding specificity of bip. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(42):29850–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieba L, Honegger A, Krebber C, Pluckthun A. Disrupting the hydrophobic patches at the antibody variable/constant domain interface: improved in vivo folding and physical characterization of an engineered scFv fragment. Protein Eng. 1997;10(4):435–44. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Kimata Y, Higashio H, Tsuru A, Kohno K. Dissociation of Kar2p/BiP from an ER sensory molecule, Ire1p, triggers the unfolded protein response in yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279(2):445–50. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil C, Walter P. Intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus: the unfolded protein response in yeast and mammals. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13(3):349–55. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raden D, Hildebrandt S, Xu P, Bell E, Doyle FJ, 3rd, Robinson AS. Analysis of cellular response to protein overexpression. Syst Biol (Stevenage) 2005;152(4):285–9. doi: 10.1049/ip-syb:20050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AS, Bockhaus JA, Voegler AC, Wittrup KD. Reduction of BiP levels decreases heterologous protein secretion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(17):10017–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudiger S, Buchberger A, Bukau B. Interaction of Hsp70 chaperones with substrates. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4(5):342–9. doi: 10.1038/nsb0597-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shusta EV, Holler PD, Kieke MC, Kranz DM, Wittrup KD. Directed evolution of a stable scaffold for T-cell receptor engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(7):754–9. doi: 10.1038/77325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shusta EV, Raines RT, Pluckthun A, Wittrup KD. Increasing the secretory capacity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of single-chain antibody fragments. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16(8):773–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt0898-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrauski C, Chapman R, Walter P. The unfolded protein response: an intracellular signalling pathway with many surprising features. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8(6):245–9. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorgjerd K, Ghafouri B, Jonsson BH, Kelly JW, Blond SY, Hammarstrom P. Retention of misfolded mutant transthyretin by the chaperone BiP/GRP78 mitigates amyloidogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2006;356(2):469–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear E, Ng DT. The unfolded protein response: no longer just a special teams player. Traffic. 2001;2(8):515–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.20801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka IM, Leung SM, McAndrew SJ, Brown JP, Hightower LE. Hsc70-binding peptides selected from a phage display peptide library that resemble organellar targeting sequences. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(34):19839–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101(3):249–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh G. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks--2003. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(8):865–70. doi: 10.1038/nbt0803-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlow M, Howard AJ, Wood JF, Voss EW, Jr., Hardman KD. 1.85 A structure of anti-fluorescein 4−4−20 Fab. Protein Eng. 1995;8(8):749–61. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.8.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittrup KD, Benig V. Optimization of amino-acid supplements for heterologous protein secretion in Saccharomyces-cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Technique. 1994;8(3):161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Raden D, Doyle FJ, 3rd, Robinson AS. Analysis of unfolded protein response during single-chain antibody expression in Saccaromyces cerevisiae reveals different roles for BiP and PDI in folding. Metab Eng. 2005;7(4):269–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]