Abstract

Bordetella pertussis is the cause of whooping cough and responsible for 300,000 infant deaths per annum. Current vaccines require 6 months to confer optimal immunity on infants, the population at highest risk. Recently, an attenuated strain of B. pertussis (BPZE1) has been developed to be used as a low-cost, live, intranasal, single-dose vaccine for newborns. Preclinical proof of concept has been established; however, it is necessary to evaluate the safety of BPZE1, especially in immunodeficient models, prior to human clinical trials. Here, the preclinical safety of BPZE1 was examined in well-characterized murine models. Immunocompetent and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) receptor knockout mice were challenged by aerosol with either virulent B. pertussis or BPZE1. The two strains colonized the lung at equal levels, but inflammation was associated with carriage of only virulent bacteria. Virulent bacteria disseminated to the liver of IFN-γ receptor-deficient mice, resulting in atypical pathology. In contrast, attenuated BPZE1 did not disseminate in either immunocompetent or immunodeficient mice and did not induce atypical pathology. In neonatal challenge models, virulent B. pertussis infection resulted in significant mortality of both immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice, whereas no mortality was observed for any neonatal mice challenged with BPZE1. BPZE1 was shown to elicit strong IFN-γ responses in mice, equivalent to those elicited by the virulent streptomycin-resistant B. pertussis Tohama I derivative BPSM, also inducing immunoglobulin G2a, a process requiring TH1 cytokines in mice. These data indicate that a live attenuated whooping cough vaccine candidate shows no signs of disseminating infection in preclinical models but rather evokes an immunological profile associated with optimal protection against disease.

Whooping cough remains a respiratory disease of considerable morbidity and mortality in children under 2 years of age. Thirty to 50 million cases and approximately 300,000 deaths are reported annually (11). This incidence is surprising considering that vaccines against whooping cough have been a constituent of mass immunization programs for many years. In fact, whooping cough is currently the fourth largest cause of vaccine-preventable death (19).

In the first part of the 20th century, inactivated whole-cell Bordetella pertussis vaccines were developed. Although they were highly efficacious, their use was associated with adverse reactogenicity, resulting in suboptimal vaccine coverage in some countries and consequently a resurgence of disease (8). In response to these issues, acellular pertussis vaccines (Pa) were developed, consisting of purified and/or detoxified B. pertussis components, such as pertussis toxin (PT), filamentous hemagglutinin, and pertactin. Pa have an improved reactogenicity profile and good efficacy (13). However, optimal immunity induced by Pa requires three administrations, and consequently, infants in the 0- to 6-month age group remain at risk (20). The longevity of Pa-mediated protection is also suboptimal, and additional booster immunizations may be required to eliminate a reservoir of infection in adolescents (41). Thus, there is a need for a highly efficacious, single-dose B. pertussis vaccine suitable for administration to neonates which evokes long-lasting immunological memory.

Recently, a live attenuated B. pertussis (BPZE1) vaccine candidate has been developed and shown to induce strong protection in infant mice upon a single intranasal administration (32). Three virulence factors have been genetically targeted to create BPZE1. PT has been modified to ablate its enzymatic activity but retain immunogenicity. The gene encoding dermonecrotic toxin (DNT) has been deleted, and the B. pertussis ampG gene has been replaced with that of Escherichia coli, thereby strongly diminishing tracheal cytotoxin (TCT) production (33).

Murine models have played an important role in pertussis vaccine research and control (22), and the potency of B. pertussis vaccines in murine models has been shown to correlate with vaccine performance in human clinical trials (35). In advance of clinical studies, the safety of candidate vaccines needs to be demonstrated; in particular, live attenuated organisms need to be examined in immunodeficient models. Although B. pertussis is strictly a respiratory pathogen, Mahon et al. have shown that virulent B. pertussis can disseminate from the lungs of immunodeficient mice, causing an atypical disease (27), and atypical disease has been observed in tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) knockout (KO) mice (44). However, reports of atypical B. pertussis disease occurring in immunodeficient humans, such as individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), are extremely rare, despite extensive circulation of the pathogen in human populations (9).

To assess the safety of BPZE1, murine respiratory and neonatal challenge models were used here. Immunocompetent and immunodeficient gamma interferon receptor (IFN-γR) KO mice were challenged with either virulent (the streptomycin-resistant B. pertussis Tohama I derivative BPSM) or attenuated (BPZE1) B. pertussis and assessed for evidence of atypical infection or disease. Survival studies using neonatal mice were carried out to determine the safety of BPZE1 in neonates. Taken together, the findings reported here indicate that BPZE1 is safe in neonatal and immunodeficient preclinical models and induces strong TH1 responses in adult mice, similar to those induced by natural infection in humans (35).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Neonatal (2- to 7-day-old) or adult (6- to 8-week-old) 129/Sv (immunocompetent) or IFN-γR KO mice (36) were used under the guidelines of the Irish Department of Health and procedures approved by the research ethics committee of the National University of Ireland, Maynooth.

Growth of B. pertussis.

B. pertussis Tohama I derivatives BPSM (31) and BPZE1 (32) have been described previously. BPSM and BPZE1 were grown at 37°C for 48 to 72 h on Bordet-Gengou agar supplemented with 15% defibrinated horse blood. Colonies were then transferred to Stainer and Scholte liquid medium containing streptomycin (30 μg/ml). Cultures were grown to mid-log phase and were maintained carefully to prevent phase modulation.

Aerosol infection.

Respiratory infection was initiated by aerosol challenge with BPSM and BPZE1 according to established protocols (15). Bacteria from mid-log-phase cultures (2 × 1010 CFU/ml) were delivered by nebulizer over a 20-min period to mice housed in an exposure chamber such that colonization of between 4 × 105 and 7 × 105 CFU/lung was achieved. This dose was chosen for consistency with previous reports of atypical pathology in this model (27) and with previous studies examining the effect of dose in the aerosol challenge model (4). Control mice were challenged with a sham aerosol of 1% (wt/vol) casein solution in sterile physiological saline.

Enumeration of viable bacteria.

Lungs and livers were removed aseptically from mice and homogenized in 1 ml of 1% (wt/vol) casein in sterile physiological saline. One hundred microliters of serially diluted homogenate from individual lungs was placed onto Bordet-Gengou agar plates in triplicate, and the numbers of CFU were determined after incubation at 37°C for 72 h.

Histopathological examination.

To assess pulmonary inflammation and injury, entire mouse lungs were fixed by immersion in 10% (vol/vol) formalin, and following paraffin embedding, 3-μm longitudinal sections were cut, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined (15). Histopathological changes were graded semiquantitatively based on the distribution, nature, and severity of the observed tissue injury and inflammation as very mild (−/+), mild (+), moderate (++), or severe (+++) by three researchers without prior knowledge of the treatment group (15).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR.

The identity of the bacterial colonies was confirmed as being virulent, non-phase-modulated B. pertussis colonies by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). This was also performed on liver and lung homogenates. RNA was isolated from cultures or homogenates using Tri reagent (Invitrogen, Renfrew, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was then examined for expression of recA, vrg6, or ptxS1. Primer pairs were as follows: recA, 5′-GCATGAAGATCGGCGTGA-3′ and 5′-CGCACCGAGGAATAGAACTTG-3′; ptxS1, 5′-CGCGCCAATCCCAACCCCTAC-3′ and 5′-GAAAGCTCCGAGGCCATGGCAG-3′; vrg6, 5′-TCTAGATACTGCCACACATGA-3′ and 5′-GTCGACGCATAACGGCTGGTGGAAGG-3′.

Cytokine recall responses to B. pertussis.

Spleens were isolated from 129/Sv mice that were sham inoculated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or inoculated with B. pertussis BPSM or BPZE via aerosol. Splenocytes were isolated by disaggregation of spleens and cultured in triplicate (±5 × 104 CFU/ml of heat-killed BPSM) at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in a total volume of 200 μl. After 72 h of incubation, culture supernatants were sampled for cytokine analysis (43).

Cytokine and specific antibody measurement.

Cytokine concentrations in culture supernatants were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using commercially available assays: IFN-γ and interleukin-5 (IL-5) (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom) were measured according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cytokine concentrations were calculated by comparison with known cytokine standards, all determinations were made in triplicate, and results are presented as mean cytokine concentration (±standard error of the mean [SEM]).

Antibody end point serum titers for immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgG subclasses (IgG1, -2a, -2b, and -3) were determined using an indirect ELISA as previously described (28). End point titers were calculated by an established method (45).

Statistical methods.

All results are expressed as the mean ± standard error. A Student t test was used to determine significance between the groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses and graphical representations were performed using Graph-Pad Prism software (Graphpad, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Attenuated BPZE1 does not cause an atypical disseminated disease in IFN-γR KO mice.

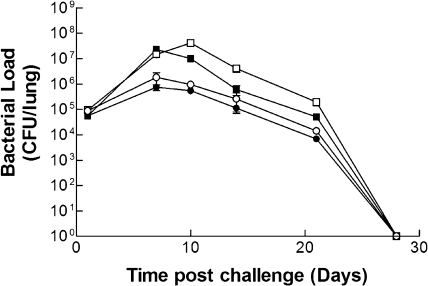

Atypical pathology and disseminated B. pertussis infection are very rare in humans. Nevertheless, virulent strains have been shown to cause atypical disease in IFN-γ or IFN-γR KO mice (23, 27) and to disseminate to the liver of IFN-γR KO mice (27), consistent with the fact that IFN-γ is known to play an important role in protection against B. pertussis (26). Therefore, the profile of infection by virulent and attenuated B. pertussis strains was examined in immunocompetent and IFN-γR KO mice. BPZE1 colonized airways of wild-type mice at levels similar to those of virulent B. pertussis (BPSM) (Fig. 1), confirming that the combined attenuation of PT, DNT, and TCT did not interfere with bacterial colonization or “take” (32). Likewise, colonization of the airways of IFN-γR KO mice was not significantly different between BPZE1 and virulent BPSM (Fig. 1), although the latter group displayed a greater bacterial burden than did their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 1). While attenuated BPZE1 colonized similarly to the virulent strain (Fig. 1), the bacterial load at days 7 and 10 postchallenge was less than that observed in mice challenged with virulent B. pertussis. This difference was significant in 129/Sv mice at days 7 (P = 0.0193) and 10 (P = 0.0007) and in IFN-γR KO mice at day 10 (P = 0.0092). No evidence of persistent infection was observed in any of these mice, with all groups clearing infection by day 28 after challenge.

FIG. 1.

Attenuated BPZE1 and virulent BPSM colonize lungs at similar levels. 129/Sv (closed symbols) and IFN-γR KO (open symbols) mice were challenged by aerosol with either BPSM (squares) or BPZE1 (circles) such that colonization of between 4 × 105 and 7 × 105 CFU/lung was achieved. Groups of mice were sacrificed at intervals after challenge, and the number of viable bacteria was estimated by performing colony counts on individual lung homogenates. Results are presented as mean (±SEM) CFU in the lungs, detected in triplicate from three mice at each time point and for each group. SEMs are present for all points but may be masked by the symbol at some data points.

Microbiological, pathological, and molecular characterization of immunocompetent and IFN-γR KO mice was carried out after challenge with virulent BPSM or attenuated BPZE1. In particular, the liver and spleen were examined for signs of disseminated infection or atypical pathology. No evidence for disseminated infection by BPZE1 in IFN-γR KO mice was found (Table 1). BPZE1 was not detected in the liver (Table 1) or spleen or blood (data not shown) of challenged IFN-γR KO mice at any time point examined. In contrast, virulent BPSM caused an atypical, disseminated disease in IFN-γR KO mice (Table 1), similar to that seen previously when the virulent B. pertussis strain W28 was employed (27). This atypical presentation was detectable in the liver from day 7 postinfection onwards. Colonies retrieved from the lung and liver were confirmed by RT-PCR for recA, vrg6, and ptxS1 as being viable, non-phase-modulated, virulent B. pertussis. Interestingly, virulent BPSM was also detected at low levels in the liver of wild-type mice (Table 1), a finding not seen previously with the W28 strain (27). Taken together, these data support the use of BPZE1 as a safe candidate vaccine in populations containing immunocompromised hosts and suggest a role for PT, DNT, or TCT alone or in combination in atypical presentation.

TABLE 1.

BPZE1 fails to disseminate to the liver

| Time postchallenge (days) | Bacterial burden for mouse strain (CFU/liver)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virulent B. pertussis (BPSM)

|

Live attenuated B. pertussis (BPZE1)

|

|||

| 129/Sv | IFN-γR KO | 129/Sv | IFN-γR KO | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 710 ± 30 | 6,530 ± 1,960 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 470 ± 105 | 2,600 ± 115 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 560 ± 120 | 1,070 ± 177 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | 50 ± 30 | 1,130 ± 540 | 0 | 0 |

129/Sv and IFN-γR KO mice were challenged with either BPSM or BPZE1. Livers from four mice per group per time point were homogenized, serially diluted, and plated in triplicate onto Bordet-Gengou agar. Results are presented as mean CFU per liver ± SEM (n = 4).

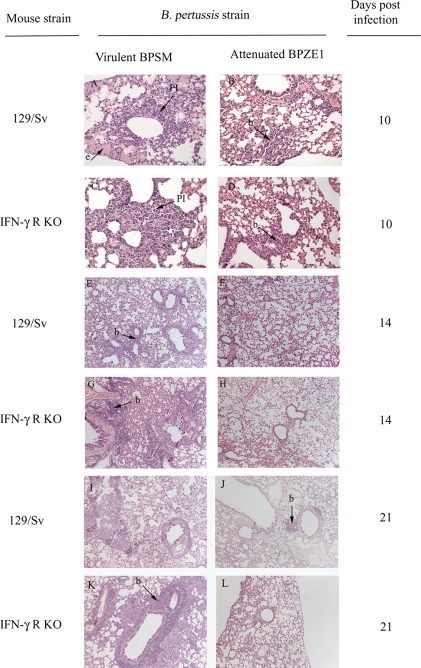

Attenuated BPZE1 does not cause atypical pathology in the airways of immunodeficient mice.

Infection with virulent B. pertussis leads to characteristic pathology in the airways of humans that can be modeled in part by murine respiratory challenge (35). The possible pathological effect of pulmonary colonization by BPZE1 or by virulent BPSM of immunocompetent and IFN-γR KO mice was assessed. Lung pathology was scored semiquantitatively, based on an assessment of the distribution, nature, and severity of injury and inflammation, as described previously (16). Lesions in infected animals were compared to those in sham-challenged controls which did not exhibit any significant tissue changes (Fig. 2). Infection of either immunocompetent or IFN-γR KO mice with BPSM resulted in the induction of typical pulmonary pathology from day 7 onwards, with increasing degrees of pulmonary inflammation characterized by multifocal intra-alveolar aggregates of admixed intact and degenerate neutrophils and macrophages, frequently adjacent to small bronchioles (Fig. 2A and C). In contrast, BPZE1 did not induce an inflammatory exudate in immunocompetent or IFN-γR KO mice (Fig. 2B and D). Periairway/perivascular lymphoid cuffing was noted, to various degrees, from day 14 onwards, in both 129/Sv (Fig. 2E and F) and IFN-γR KO (Fig. 2G and H) mice challenged with either BPSM (Fig. 2E and G) or BPZE1 (Fig. 2F and H). Airway pathology (+++) was notable at day 21 in both 129/Sv and IFN-γR KO mice challenged with virulent BPSM (Fig. 2I and K). In contrast, BPZE1-challenged mice displayed no airway damage (−/+) (Fig. 2J and L), but development of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue was prominent, suggesting the induction of specific immunity. Histological scores in BPZE1-challenged mice were minimal (i.e., did not exceed +) in any lung sections, in contrast to the widespread pathology recorded for BPSM-infected mice (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Virulent B. pertussis BPSM (A, C, E, G, I, and K) induces pathology not seen with attenuated BPZE1 (B, D, F, H, J, and L) in the lungs of 129/Sv (A, B, E, F, I, and J) or IFN-γR KO (C, D, G, H, K, and L) mice, at day 10, 14, or 21 postchallenge. Periairway/perivascular lymphoid cuffing was noted to various degrees in the lungs of 129/Sv (E and F) or IFN-γR KO (G and H) mice on day 14 after infection with either BPSM (E and G) or BPZE1 (F and H), indicative of the formation of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue hyperplasia (b). BPZE1-challenged mice showed reduced levels of pulmonary inflammation (PI) and inflammatory exudate (e) compared to those of mice challenged with BPSM. High levels of pathology (+++) are noted at day 21 postinfection in 129/Sv (I and J) and IFN-γR KO (K and L) mice challenged with BPSM (I and K), whereas no airway damage was observed (−/+) in BPZE1-challenged mice (J and L). Original magnification, ×200 (A to D) or ×100 (E to L). Lung tissue was fixed, embedded, and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Histology was scored using a previously described semiquantitative system (14).

TABLE 2.

BPZE1 does not induce inflammatory pathology in a murine model

| Time postchallenge (days) | Pathology of experimental groupa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virulent B. pertussis (BPSM)

|

Live attenuated B. pertussis (BPZE1)

|

|||

| 129/Sv | IFN-γR KO | 129/Sv | IFN-γR KO | |

| 0 (3 h) | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | − |

| 7 | + | + | + | −/+ |

| 10 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| 14 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| 21 | +++ | +++ | −/+ | −/+ |

129/Sv and IFN-γR KO mice were challenged with either BPSM or BPZE1. Lungs were then removed at 0, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days postinfection; embedded in paraffin; and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Pathological changes were then scored semiquantitatively, based on the distribution, nature, and severity of the observed pulmonary injury and inflammation, as very mild (−/+), mild (+), moderate (++), or severe (+++) (n = 3).

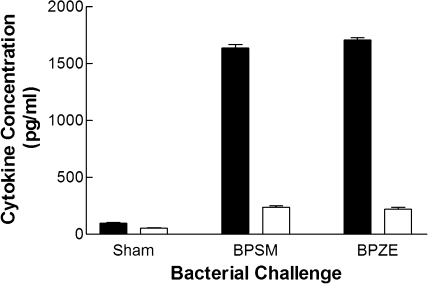

Attenuated BPZE1 mimics wild-type infection in generating a TH1-polarized response.

Immunity induced by existing acellular whooping cough vaccines wanes, leading to potential reservoirs for infection in adolescents who have previously received vaccination (2, 38). Natural infection, however, induces a strong TH1 response, which confers long-lasting immunity (26, 34). For this reason, it is likely that closely mimicking natural infection could result in improved efficacious vaccines against B. pertussis. As BPZE1 is a live vaccine, delivered directly to a mucosal surface, and mimics natural infection (32), the nature of the immune response induced by BPZE1 was investigated. Mice were challenged with either virulent BPSM, attenuated BPZE1, or a sham inoculation, and immune responses were examined at day 40 postchallenge, a time point when bacterial infection had been cleared. Sham-challenged mice produced minimal recall responses to inactivated B. pertussis, as expected (Fig. 3). In contrast, BPSM challenge of immunocompetent mice evoked high levels of IFN-γ and low levels of IL-5 upon restimulation. Similarly, BPZE1 induced high levels of IFN-γ and low levels of IL-5 (Fig. 3) in response to restimulation by inactivated B. pertussis, typical of a strong TH1-type response.

FIG. 3.

Priming with either virulent B. pertussis BPSM or attenuated BPZE1 induced a TH1-polarized response. Cell-mediated immune responses were examined from spleen cell cultures after sham inoculation, virulent BPSM infection, or attenuated BPZE1 challenge. IFN-γ (closed bars) and IL-5 (open bars) recall responses were measured in spleen cell culture supernatant after restimulation with inactivated BPSM at 1 × 104 CFU/ml. Determinations were made from four mice, and each was carried out in triplicate; results are expressed as means (±SEM).

T-cell-derived cytokines have a major influence on the class of immunoglobulin secreted from B cells (18). The presence of IL-4 is necessary for class switching from IgM to IgG1 and IgE (39), whereas IFN-γ is essential for switching to an IgG2a response in mice (17). IFN-γ is known to play an important role in protection against B. pertussis (8, 12). To further analyze the immune response, serum samples from the same mice were examined for B. pertussis-specific total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgE. As expected, only baseline levels of all antibody classes were observed in sham-challenged mice. In contrast, BPZE1 challenge induced a strong B. pertussis-specific IgG response (1/30,000) but little IgE (<1/10). The predominant subclass of B. pertussis-specific IgG was IgG2a (1/2,100), while IgG1 was found at much lower concentrations (1/100) (Table 3). This is characteristic of a TH1-influenced humoral response, closely resembling that shown previously for natural infection (34). Quantitatively and qualitatively similar antibody titers were observed in BPZE1-immunized 129/Sv mice (total IgG, 1/45,000; IgG2a, 1/4,000; IgG1, 1/250). Together, these results show that BPZE1 induces strong TH1-polarized immunity in adult mice similar to that generated through virulent challenge and associated with optimal immune responses in humans (2).

TABLE 3.

BPZE1 induces IgG2a but not IgG1 or IgE in challenged mice

| Immunoglobulin class/subclass | Serum end point titer for mouse groupa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | BPZE1 immunized | BPSM infected | |

| Total IgG | <1/10 | 1/30,000 | 1/35,000 |

| IgG1 | <1/10 | 1/100 | 1/200 |

| IgG2a | <1/10 | 1/2,100 | 1/1,900 |

| IgG2b | <1/10 | 1/600 | 1/1,000 |

| IgG3 | <1/10 | 1/100 | 1/100 |

| IgE | <1/10 | <1/10 | 1/10 |

BALB/c mice were challenged with virulent BPSM, attenuated BPZE1, or a sham inoculum of 1% (wt/vol) casein in PBS. At day 40 postinfection, serum samples were taken from all groups of mice and analyzed by ELISA for B. pertussis-specific total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgE. Results are expressed as mean end point titers; experiments were performed three times, for triplicates in each case.

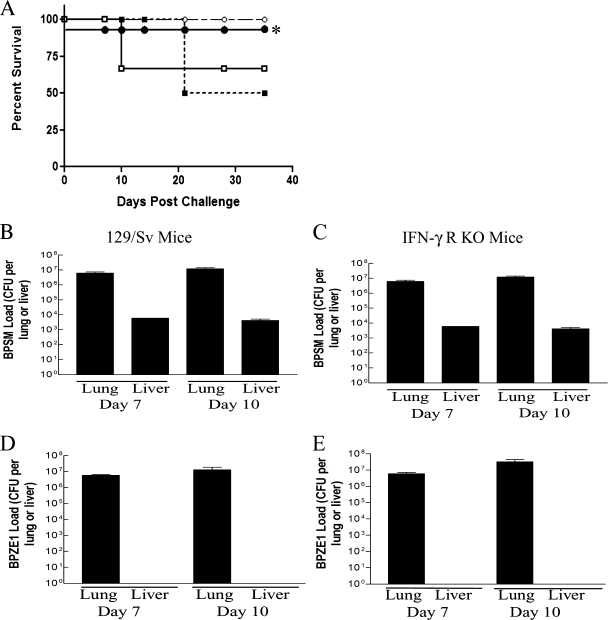

Attenuated BPZE1 is safe in a neonatal mouse model.

Virulent B. pertussis can cause a lethal infection in neonatal mice (41). Therefore, groups of neonatal (0- to 7-day-old) wild-type (129/Sv) or IFN-γR KO mice were challenged with BPSM or BPZE1 or sham challenged with PBS, and survival was monitored over a period of 35 days. A survival rate of 100% was observed in the PBS control group. As with other virulent strains (42), BPSM infection resulted in high rates of mortality in neonatal animals, with a 40 to 50% fatality rate in IFN-γR KO and immunocompetent mice prior to day 35 postchallenge (Fig. 4A). In marked contrast, no mortality was seen when immunocompetent or immunocompromised mice were challenged with BPZE1.

FIG. 4.

(A) BPZE1 does not cause lethal infection in neonatal KO mice. Neonate IFN-γR KO (open symbols) or 129/Sv (closed symbols) mice (less than 7 days) were infected with either virulent B. pertussis BPSM (squares) or BPZE1 (circles). Mice were observed over a period of 35 days, and survival was recorded. *, note that BPZE1-challenged 129/Sv mice showed 100% survival but that the curve has been offset from 100% for clarity in this figure. (B) BPZE1 did not disseminate to the liver of neonatal 129/Sv (wild-type) or IFN-γR KO mice. Neonatal 129/Sv and IFN-γR KO mice were challenged with either virulent BPSM or attenuated strain BPZE1, mice were then sacrificed at days 7 and 10, and lungs and livers were removed and examined for B. pertussis colonization. Dissemination was reduced in 129/Sv mice compared to IFN-γR KO mice challenged with BPSM. Results are presented as mean (±SEM) CFU in the liver, detected individually from five mice from each group.

Since neonatal mice and humans are less immunocompetent than adults (25), the ability of neonatal mice to restrict a BPZE1 infection to the lung was therefore examined. Liver samples were taken from neonatal mice at days 7 and 10 postinfection and examined for bacterial load; the time points were chosen to reflect the maximum likelihood of detecting atypical infection. Mice that received virulent BPSM showed considerable signs of disseminating infection (Fig. 4B and D). Similar levels of bacterial burden were seen in immunocompetent and IFN-γR KO neonatal mice challenged with virulent BPSM (Fig. 4B and D). In contrast, neonatal mice that received attenuated BPZE1 showed no signs of disseminating systemic infection, distress, or weight loss (Fig. 4C and E and data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the safety of a recently developed, attenuated strain of B. pertussis, BPZE1, intended for use as a low-cost, live, intranasal vaccine against whooping cough (32). Previously, virulent B. pertussis has been shown to cause an atypical disease in IFN-γR KO mice (27). BPZE1 was unable to cause an atypical disease in IFN-γR KO mice. It failed to induce the lung pathology associated with virulent B. pertussis and, in contrast to virulent bacteria, was shown to be safe in a neonate mouse model, opening the possibility of this new-generation live attenuated vaccine being used in neonates. Vaccination with BPZE1 induced strong TH1 responses, similar to those elicited by natural infection.

Unlike Bordetella bronchiseptica, reports of atypical B. pertussis disease in immunodeficient humans, such as individuals infected with HIV, are rare (21, 40). B. pertussis is known to cause atypical pathology in certain immunodeficient mouse strains, notably atypical disease in IFN-γR KO mice, NK-deficient mice, and mice lacking TNF-α (6, 27, 44). It was therefore important to document whether a live attenuated vaccine candidate, BPZE1, could cause atypical pathology in immunocompromised hosts. The IFN-γR model was chosen for this study because atypical disease is striking in this model and the absence of IFN-γ is also a key aspect of atypical disease in the NK-deficient model (4). The aerosol challenge model was also chosen because the effects of bacterial dose, mouse strain, and other parameters on the immune response are well characterized (4). Virulent B. pertussis BPSM colonized the livers of both mouse strains, albeit to a significantly higher degree in IFN-γR KO mice than in immunocompetent mice. In contrast, attenuated BPZE1 failed to disseminate to the liver of either mouse strain, despite levels of lung colonization similar to those for BPSM. These data confirm the role of IFN-γ in the restriction of B. pertussis to the airways of infected individuals and support the use of attenuated B. pertussis as a safe vaccine for immunodeficient individuals. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the precise nature of the role of IFN-γ in B. pertussis infection, which seems nonredundant. While challenge with virulent B. pertussis strains of most other KO mice has only subtle influences on pathological presentation, it will be important to examine the effects of immunization in other models, especially TNF-α KO mice (44) and mice lacking CD4+ cells; however, we have found no evidence of disseminated infection by BPZE1 in SCID mice by using the related intranasal challenge model (data not shown). In this study, the virulent BPSM strain of B. pertussis showed some dissemination in immunocompetent mice not seen in previous studies when the W28 strain was used (27); it is unclear why the two virulent strains are different in this regard, but it may reflect the extended culture history of the W28 strain compared to that of BPSM.

In addition to the issues of disseminated infection and atypical pathology, the possibility of delayed clearance or possible chronic infection by the live vaccine strain in immunocompromised models required attention. Berkowitz et al. (5) reported extended periods of infection accompanied by dyspnea in an immunocompromised whooping cough patient; increased severity and delayed clearance have also been noted both in HIV/AIDS patients and in recently vaccinated HIV-positive children (1, 5, 10, 12). Barbic et al. also observed an increased bacterial load in the lungs of B. pertussis-infected IFN-γ-depleted mice (3). Although reports of persistent infection and severe disease in immunocompromised humans are rare (9), these findings, coupled with reports of poor IFN-γ expression by infants (24), prompted an examination of the persistence of infection and pathology in mouse models. Infection with either bacterial strain in adult immunodeficient or immunocompetent models resolved by day 28, suggesting that even individuals with impaired TH1 function would retain the ability to clear the challenge. These data also confirm that attenuations in BPZE1 do not compromise colonization, which is important to support the establishment of strong immune responses (32).

The three genetic alterations present in BPZE1 were designed to maintain colonization and immunogenicity while reducing pathology. This was achieved through the genetic inactivation of the highly immunogenic PT rather than its removal, the total removal of DNT, and the reduction of secreted TCT through E. coli ampG expression. Lung samples from mice challenged with the attenuated strain showed only a mild cellular infiltration on day 10, consistent with the induction of specific immune responses, whereas over 21 days virulent BPSM infection induced increasing pathology in mice, characterized by immune cell infiltration, the presence of a fibrinous exudate, and obstruction of the alveolar spaces (Fig. 2).

B. pertussis is a significant cause of infant death and is able to cause a lethal infection in neonatal mouse models (42). Virulent BPSM infection resulted in high mortality in both immunocompetent 129/Sv and IFN-γR KO neonatal mice. In marked contrast, all immunocompetent and immunocompromised neonatal mice survived BPZE1 challenge, showing no signs of distress, weight loss, or atypical disease. This finding attests to the safety of BPZE1 in mice and, in combination with other studies (33), increases confidence in the proposed use of BPZE1 as a neonatal vaccine.

It has been shown elsewhere that the infant immune system has a poor capacity to generate TH1-type responses (29), and most newborn children have TH2-type skewed immune responses (37). Current Pa vaccines have been shown to induce TH2-type responses (14, 15, 30). TH1-dominated immune responses have been linked with optimal immunity against B. pertussis (2, 4, 7, 34). The use of a live vaccine delivered directly to mucosal surfaces closely imitates natural infection, and the ability of the bacteria to persist until the initiation of adaptive responses allows for the potential to develop strong memory responses. In adult mice, BPZE1 mimicked wild-type infection by eliciting a specific IFN-γ/IgG2a response, but little IL-5, IgG1, or IgE. It would be unwise to attempt a precise correlation of immunological memory in murine models with the longevity of protection in humans; nevertheless, this study demonstrates two important attributes of vaccination with BPZE1: first, the ability of BPZE1 to produce a strong TH1-polarized response that could potentially skew formative immune responses away from atopy-associated TH2-type priming (28), and second, the ability of vaccination to produce a response which is similar to natural infection in both quality and quantity (26, 35).

In view of the impact of whooping cough in early childhood (11) despite current wide vaccination coverage, there is a need for novel whooping cough vaccines to be included in mass immunization programs. Previous preclinical data on protective immunogenicity (32) and the findings from this study support the use of a live attenuated B. pertussis vaccine strain, BPZE1, as a safe candidate suitable for vaccinations of neonates, even of populations that include immunodeficient subjects. The data presented here indicate that BPZE1 lacks key virulence factors that are linked to atypical pathology and lethal infection in neonates. BPZE1 does not cause atypical pathology in either adult or neonatal IFN-γR KO mice and, consequently, meets the preclinical criteria for a candidate vaccine against whooping cough. It is now possible to consider BPZE1 as a potential live human vaccine against whooping cough.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the European Commission under the seventh framework, grant agreement number 201502 (CHILD-Innovac). C.M.S. is an IRCSET and John Hume scholar.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson, P. C., T. C. Wu, B. D. Meade, M. Rubin, C. R. Manclark, and P. A. Pizzo. 1989. Pertussis in a previously immunized child with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Pediatr. 115:589-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausiello, C. M., R. Lande, F. Urbani, A. la Sala, P. Stefanelli, S. Salmaso, P. Mastrantonio, and A. Cassone. 1999. Cell-mediated immune responses in four-year-old children after primary immunization with acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect. Immun. 67:4064-4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbic, J., M. Leef, D. Burns, and R. Shahin. 1997. Role of gamma interferon in natural clearance of Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect. Immun. 65:4904-4908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnard, A., B. P. Mahon, J. Watkins, K. Redhead, and K. H. Mills. 1996. Th1/Th2 cell dichotomy in acquired immunity to Bordetella pertussis: variables in the in vivo priming and in vitro cytokine detection techniques affect the classification of T-cell subsets as Th1, Th2 or Th0. Immunology 87:372-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkowitz, D. M., R. I. Bechara, and L. L. Wolfenden. 2007. An unusual cause of cough and dyspnea in an immunocompromised patient. Chest 131:1599-1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne, P., P. McGuirk. S. Todryk, and K. H. Mills. 2004. Depletion of NK cells results in disseminating lethal infection with Bordetella pertussis associated with a reduction of antigen-specific Th1 and enhancement of Th2, but not Tr1 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 34:2579-2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahill, E. S., D. T. O'Hagan, L. Illum, A. Barnard, K. H. G. Mills, and K. Redhead. 1995. Immune responses and protection against Bordetella pertussis infection after intranasal immunization of mice with filamentous haemagglutinin in solution or incorporated in biodegradable microparticles. Vaccine 13:455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherry, J. D. 1992. Pertussis: the trials and tribulations of old and new pertussis vaccines. Vaccine 10:1033-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohn, S. E., K. L. Knorr, P. H. Gilligan, M. L. Smiley, and D. J. Weber. 1993. Pertussis is rare in human immunodeficiency virus disease. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 147:411-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colebunders, R., C. Vael, K. Blot, J. Van Meerbeeck, J. Van den Ende, and M. Ieven. 1994. Bordetella pertussis as a cause of chronic respiratory infection in an AIDS patient. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:313-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowcroft, N. S., and R. G. Pebody. 2006. Recent developments in pertussis. Lancet 367:1926-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doebbeling, B., M. L. Feilmeier, and L. A. Herwaldt. 1990. Pertussis in an adult man infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 161:1296-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englund, J. A., M. D. Decker, K. M. Edwards, M. E. Pichichero, M. C. Steinhoff, and E. L. Anderson. 1994. Acellular and whole-cell pertussis vaccines as booster doses: a multicenter study. Pediatrics 93:37-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ennis, D. P., J. Cassidy, and B. P. Mahon. 2005. Acellular pertussis vaccine protects against exacerbation of allergic asthma due to Bordetella pertussis in a murine model. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:409-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ennis, D. P., J. Cassidy, and B. P. Mahon. 2005. Whole-cell pertussis vaccine protects against Bordetella pertussis exacerbation of allergic asthma. Immunol. Lett. 97:91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ennis, D. P., J. Cassidy, and B. P. Mahon. 2004. Prior Bordetella pertussis infection modulates allergen priming and the severity of airway pathology in a murine model of allergic asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34:1488-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelman, F., I. Katona, T. Mosmann, and R. Coffman. 1988. IFN-gamma regulates the isotypes of Ig secreted during in vivo humoral immune responses. J. Immunol. 140:1022-1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelman, F. D., J. Holmes, I. M. Katona, J. F. Urban, M. P. Beckmann, L. S. Park, K. A. Schooley, R. L. Coffman, T. R. Mosmann, and W. E. Paul. 1990. Lymphokine control of in vivo immunoglobulin isotype selection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 8:303-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsyth, K. D., C.-H. Wirsing von Konig, T. Tan, J. Caro, and S. Plotkin. 2007. Prevention of pertussis: recommendations derived from the second Global Pertussis Initiative roundtable meeting. Vaccine 25:2634-2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant, C. C., R. Roberts, R. Scragg, J. Stewart, D. Lennon, D. Kivell, R. Ford, and R. Menzies. 2003. Delayed immunisation and risk of pertussis in infants: unmatched case-control study. BMJ 326:852-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janda, W. M., E. Santos, J. Stevens, D. Celig, L. Terrile, and P. C. Schreckenberger. 1994. Unexpected isolation of Bordetella pertussis from a blood culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2851-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendrick, P. L., G. Eldering, M. K. Dixon, and J. Misner. 1947. Mouse protection tests in the study of pertussis vaccine: a comparative series using the intracerebral route for challenge. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 37:803-810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khelef, N., C. M. Bachelet, B. B. Vargaftig, and N. Guiso. 1994. Characterization of murine lung inflammation after infection with parental Bordetella pertussis and mutants deficient in adhesins or toxins. Infect. Immun. 62:2893-2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis, D., A. Larsen, and C. Wilson. 1986. Reduced interferon-gamma mRNA levels in human neonates. Evidence for an intrinsic T cell deficiency independent of other genes involved in T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 163:1018-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahon, B. P. 2001. The rational design of vaccine adjuvants for mucosal and neonatal immunization. Curr. Med. Chem. 8:1057-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahon, B. P., M. T. Brady, and K. H. G. Mills. 2000. Protection against Bordetella pertussis in mice in the absence of detectable circulating antibody: implications for long-term immunity in children. J. Infect. Dis. 181:2087-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahon, B. P., B. J. Sheahan, F. Griffin, G. Murphy, and K. H. G. Mills. 1997. Atypical disease after Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection of mice with targeted disruptions of interferon-gamma receptor or immunoglobulin μ chain genes. J. Exp. Med. 186:1843-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchant, A., T. Goethebuer, M. Ota, I. Wolfe, S. Ceesay, D. De Grote, T. Corrah, S. Bennett, J. Wheeler, K. Huygen, P. Aaby, W. McAdam, and M. Newport. 1999. Newborns develop a Th1-type response to Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus-Calmette-Guerin vaccination. J. Immunol. 163:2249-2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marodi, L. 2002. Down-regulation of Th1 responses in human neonates. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 128:1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mascart, F., M. Hainaut, A. Peltier, V. Verscheure, J. Levy, and C. Locht. 2007. Modulation of the infant immune responses by the first pertussis vaccine administrations. Vaccine 25:391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menozzi, F. D., R. Mutombo, G. Renauld, C. Gantiez, J. H. Hannah, E. Leininger, M. J. Brennan, and C. Locht. 1994. Heparin-inhibitable lectin activity of the filamentous hemagglutinin adhesin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 62:769-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mielcarek, N., A.-S. Debrie, D. Raze, J. Bertout, C. Rouanet, A. B. Younes, C. Creusy, J. Engle, W. E. Goldman, and C. Locht. 2006. Live attenuated B. pertussis as a single-dose nasal vaccine against whooping cough. PLoS Pathog. 2:e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mielcarek, N., A.-S. Debrie, D. Raze, J. Quatannens, J. Engle, W. E. Goldman, and C. Locht. 2006. Attenuated Bordetella pertussis: new live vaccines for intranasal immunisation. Vaccine 24:S54-S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills, K. H., A. Barnard, J. Watkins, and K. Redhead. 1993. Cell-mediated immunity to Bordetella pertussis: role of Th1 cells in bacterial clearance in a murine respiratory infection model. Infect. Immun. 61:399-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mills, K. H. G., M. Ryan, E. Ryan, and B. P. Mahon. 1998. A murine model in which protection correlates with pertussis vaccine efficacy in children reveals complementary roles for humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection against Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 66:594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller, U., S. Reis, J. Hemmi, R. Pavloviv, R. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1994. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 262:1918-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prescott, S. L., C. Macaubas, B. J. Holt, T. B. Smallacombe, R. Loh, and P. D. Sly. 1998. Transplacental priming of the human immune system to environmental allergens: universal skewing of initial T cell responses toward Th2 cytokine profile. J. Immunol. 160:4730-4737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salmaso, S., P. Mastrantonio, S. G. F. Wassilak, M. Giuliano, A. Anemona, A. Giammanco, A. E. Tozzi, M. L. Ciofi degli Atti, and D. Greco. 1998. Persistence of protection through 33 months of age provided by immunization in infancy with two three-component acellular pertussis vaccines. Vaccine 16:1270-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snapper, C. M., F. D. Finkelman, and W. E. Paul. 1988. Regulation of IgG1 and IgE production by interleukin 4. Immunol. Rev. 102:51-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trøseid, M., T. Ø. Jonassen, and M. Steinbakk. 2006. Isolation of Bordetella pertussis in blood culture from a patient with multiple myeloma. J. Infect. 52:e11-e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von König, C. H., S. Halperin, M. Riffelmann, and N. Guiso. 2002. Pertussis of adults and infants. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:744-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss, A. A., and M. S. Goodwin. 1989. Lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis mutants in the infant mouse model. Infect. Immun. 57:3757-3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfe, D. N., E. M. Goebel, O. N. Bjornstad, O. Restif, and E. T. Harvill. 2007. The O antigen enables Bordetella parapertussis to avoid Bordetella pertussis-induced immunity. Infect. Immun. 75:4972-4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolfe, D. N., P. B. Mann, A. M. Buboltz, and E. T. Harvill. 2007. Delayed role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in overcoming the effects of pertussis toxin. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1228-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zachariadis, O., J. Cassidy, C. Brady, and B. P. Mahon. 2006. γδ T cells regulate the early inflammatory response to Bordetella pertussis infection in the murine respiratory tract. Infect. Immun. 74:1837-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]