Abstract

Aleutian disease (AD), a common infectious disease in farmed minks worldwide, is caused by Aleutian mink disease virus (AMDV). Serodiagnosis of AD in minks has been based on detection of AMDV antibodies by counterimmunoelectrophoresis (CIE) since the 1980s. The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based on recombinant virus-like particles (VLPs) for identifying AMDV antibodies from mink sera. AMDV capsid protein (VP2) of a Finnish wild-type strain was expressed by the baculovirus system in Spodoptera frugiperda 9 insect cells and was shown to self-assemble to VLPs (with an ultrastructure similar to that of the actual virion). A direct immunoglobulin G ELISA was established using purified recombinant AMDV VP2 VLPs as an antigen. Sera from farmed minks were collected to evaluate the AMDV VP2 ELISA (n = 316) and CIE (n = 209) based on AMDV VP2 recombinant antigen in parallel with CIE performed using a commercially available traditional antigen. CIE performed with the recombinant antigen had a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and ELISA a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 97%, with reference to CIE performed with the commercial antigen. The results show that the recombinant AMDV VP2 VLPs are antigenic and that AMDV VP2 ELISA is sensitive and specific and encourage further development of the method for high-throughput diagnostics, involving hundreds of thousands of samples in Finland annually.

Aleutian mink disease virus (AMDV) is a member of the genus Amdovirus, subfamily Parvovirinae, family Parvoviridae. The icosahedral nonenveloped virion contains a 4.8-kb single-stranded DNA genome and three nonstructural (NS1, NS2, and putative NS3) and two structural (VP1 and VP2) proteins (9, 10, 29). Several strains, ranging in pathogenicity from nonpathogenic (AMDV-G) to highly pathogenic (e.g., AMDV-Utah 1, -United, and -K), have been identified (6, 7, 18, 19). AMDV causes an immune-mediated disease, called Aleutian disease (AD), in minks (Mustela vison) and other mustelids (16, 20, 22, 24, 28).

The disease manifestation varies, from mild nonprogressive to fatal progressive disease in adult minks and acute fatal pneumonia in mink kits, depending on the virus strain and host factors (10). Nonpersistent infections have also been described (10). The most serious form of AD, known as classical AD, is associated with viremia, plasmacytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia, high AMDV antibody levels, formation of infectious immune complexes, and glomerulonephritis (10, 19). Clinical signs include lethargy, anemia, anorexia, cachexia, polydipsia, poor pelt, infertility, renal failure, uremia, neurological symptoms, and clotting abnormalities (17). Minks with classical AD die, depending on the mink genotype and the virus strain, within 2 months to 4.5 years after infection (17).

AMDV can be found in all mink breeding countries, and it causes considerable economic losses to farmers, e.g., in the form of decreased production, loss of breeding animals, and low-quality fur (17). The infection is usually persistent, often fatal, and there is no effective vaccine or treatments against the disease (3, 11, 26, 27). Transmission of AMDV occurs horizontally by direct and indirect contact and vertically from dams to kits (17). Furthermore, the virus is persistent in the environment and resistant to various physical and chemical treatments (17). Due to all of this, it is very challenging to sanitize an infected farm. At the moment, the only effective means of eradicating AD from farms is serological screening, subsequent identification, elimination of all antibody-positive animals, and pursuit of strict sanitary measures.

Diagnosis of AD in minks is based primarily on the clinical signs and detection of AMDV antibodies. Several nonspecific (iodine agglutination test, serum electrophoresis, and glutaraldehyde test) and specific (indirect immunofluorescence, complement fixation, and counterimmunoelectrophoresis [CIE]) tests were developed in the late 1960s and 1970s (17). At the moment, CIE (also abbreviated CCIE, CIEP, and CCE) is used for routine detection of AMDV. CIE is based on the formation and visual detection of immune complexes on an agarose gel after electrophoresis. During the 1970s, the assay has been carried out with organ-produced viral antigen (12). Since the 1980s, an in vitro-grown antigen (strain AMDV-G; Crandell feline kidney cells) has been applied (1). Other immunoelectrophoretic assays have also been developed in order to increase sensitivity and/or specificity: modified counterelectrophoresis (15), indirect counter-current electrophoresis (1), counter-current line absorption immunoelectrophoresis (CCLAIE) (2, 5), additive CIE (32), and rocket line immunoelectrophoresis (4). These have not been widely used in routine field testing, due to various reasons, e.g., because costs are high or because the assays are time-consuming or laborious to perform. The most sensitive immunoelectrophoretic assay is CCLAIE (2). When test results (n = 3,321) for CIE were compared to the results for CCLAIE, CIE showed a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 99% (2). Also, the titer was higher in CCLAIE (1:4,096) than in CIE (1:256) (2).

Recombinant AMDV VP2 proteins have been expressed (13, 14, 34, 35) and shown to be antigenic and able to form virus-like particles (VLPs) (13, 14, 34). However, only a few diagnostic applications have been described (3, 14, 35), and published comparative data are scarce. Clemens et al. (14) demonstrated that the recombinant VLPs are more sensitive and give higher titers in CIE than the in vitro-produced AMDV-G antigen (n = 10). Zeng et al. (35) expressed AMDV VP2 protein in prokaryotic cells and used the purified antigen in CIE. The detection results showed 94.3% identity with a commercially available antigen in CIE (n = 54). Three enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based methods have been described for diagnosis of AMDV infection from mink serum samples (3, 11, 33). The only study comparing ELISA and CIE test results was done more than 25 years ago (33). In this study, fluorocarbon-activated AMDV (Guelph strain) was used as an antigen in both tests (n = 1,329) and the conclusion was that the ELISA method has a high rate of false-negative reactions. Commercial applications of ELISA assays for serodiagnosis of AD in minks are lacking. To our knowledge, two ELISAs have been developed for ferrets: one by Avecon Diagnostics (Bath, PA) and the other by the University of Georgia (http://www.vet.uga.edu/VPP/clerk/schuler/index.php). The former is commercially available.

In Finland, the Fur Animal Feed Laboratory started to test farmed minks for AMDV by CIE in 1980. In 1981 and 1982, the seroprevalence was approximately 50% to 60%. Since then, it has decreased considerably due to control measures in infected farms, varying from 3% to 11% in 1990 to 2008. In 2008, almost 500,000 serum samples from minks were tested for AMDV antibodies in Finland, and the number is increasing each year.

In this study, a recombinant VP2 protein antigen based on a wild-type Finnish AMDV strain and subsequently an ELISA-based method for detecting AMDV antibodies in minks were developed. The purified recombinant antigen was used in both CIE and ELISA, and the results were evaluated in comparison with those for the existing commercially available CIE antigen and method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples.

A total of 525 serum samples were collected from farmed minks in Finland. Blood was obtained by toenail cutting and collected into glass capillary tubes. After centrifugation, the serum samples were stored at −20°C until processed.

DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from the mesenteric lymph node of a Finnish mink, designated C8, in 2005 as previously described (21).

PCR.

The AMDV VP2 gene (1,944 nucleotides), corresponding to nucleotide positions 2406 to 4349 of the complete sequence of AMDV-G (GenBank accession no. NC_001662), was amplified from the isolated DNA by PCR using the following primers: forward, 5′-TTT GGA TCC AAT AGA GGA AAT GGA TTC TGC TG-3′ (BamHI digestion site underlined); reverse, 5′-TTT GAC GTC TTA GTA GAT ATA TTT GAT AGT GCT TCT TCC-3′ (PstI digestion site underlined). The PCRs were performed with 100-μl volumes containing 5 μl template DNA, 1× PCR buffer with (NH4)2SO4, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM each primer, and 2.5 U Taq polymerase (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada). The amplification mixture was initially incubated at 95°C for 10 min and then cycled 5 times through denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 54°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 3 min, after which it was cycled 30 times through denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 59°C, and elongation at 72°C for 2.5 min, with a final, 10-min elongation step at 72°C. The PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified from the agarose gel with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Construction of a recombinant plasmid and expression of the recombinant VP2 protein.

The purified PCR product and the pGEM-T plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI) were ligated and transformed into Escherichia coli JM109 competent cells (Promega, Madison, WI). The bacteria were suspended in Luria broth (LB), grown for 1 h in a shaker, plated on LB-ampicillin (250 μg/ml)-IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) plates, and incubated overnight (o/n) at 37°C. White bacterial colonies (generally containing the insert) were transferred in LB containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and grown o/n at 37°C. Plasmids were purified from the bacterial culture with a QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The purified plasmid DNA including the VP2 insert, the pGEM-T vector, and the baculovirus transfer plasmid pAcYML1 (kindly provided by Johan Peränen, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki; the plasmid construct was modified from that reported by Matsuura et al. [23]) were digested with restriction enzymes BamHI and PstI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and gel purified. The VP2 insert was ligated into baculovirus transfer plasmid pAcYML1 o/n at 14°C (1 μl T4 DNA ligase [400 U/μl], 1 μl 10× T4 DNA ligase buffer [New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA], 1 μl insert, 0.5 μl vector, and 10 μl H2O). The transfer plasmid was further transformed into E. coli and grown as described above. The bacterial suspension was purified with an EndoFree plasmid maxikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Two hundred fifty nanograms of BaculoGold baculovirus DNA (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and 2 μg of purified plasmid construct DNA were mixed in transfection buffer containing FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and Sf-900 medium (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom). The mixture was then applied to Spodoptera frugiperda 9 (ATCC CRL-1711; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) cells (3 × 106 cells per 25-cm2 flask) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature (RT) and 1 h at 27°C. The transfection medium was then removed, and the cells were incubated in fresh growth medium (Sf-900 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum [Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom], 1× glutamine-penicillin-streptomycin [Haartbio, Helsinki, Finland], and 0.25 mg/ml Fungizone [Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rueil-Malmaison, France]) at 27°C for 4 days. The cells and supernatant were harvested by low-speed centrifugation. The supernatant was stored at 4°C and used for subsequent infections. One milliliter of the supernatant was used for 25-cm2, 2 ml for 50-cm2, and 4 ml for 75-cm2 flasks. The infected S. frugiperda 9 cells were incubated at 27°C for 48 to 72 h, until CPE was evident. The cell paste was washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and stored at −70°C until processed.

Sequencing.

The gel-purified pGEM-T-VP2 construct was sequenced with commercial primers (M13, T7, and SP6) by the Haartman Institute core unit (Helsinki, Finland).

Extraction and purification of the recombinant VP2 protein.

The recombinant proteins were extracted and purified from the cell paste in Tris-based buffer with heating as previously described (31), with slight modifications. The cell paste was sonicated and heated at 50°C, and after centrifugation, the supernatant was used to establish recombinant VP2 CIE and ELISA.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

The infected and noninfected cell pellets were diluted 1:100 and the purified antigen was diluted 1:10 in reducing Laemmli sample buffer, heated for 5 min at 95°C, and electrophoresed through a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel. The proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. For Western blot analysis, the proteins were transferred from the SDS-PAGE gel to a nitrocellulose membrane. Blocking of the membrane and both mink serum and conjugate dilutions were done with TEN (0.5 M Tris, 1.5 M sodium chloride, 0.05 M EDTA) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 1% nonfat milk powder. The membranes were blocked o/n at 4°C and incubated with pooled sera from AMDV-infected and noninfected minks (1:300 dilution) for 1 h at RT. After being washed with TEN containing 0.05% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-cat immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:5,000 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at RT. After the second wash, the reaction was visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) staining.

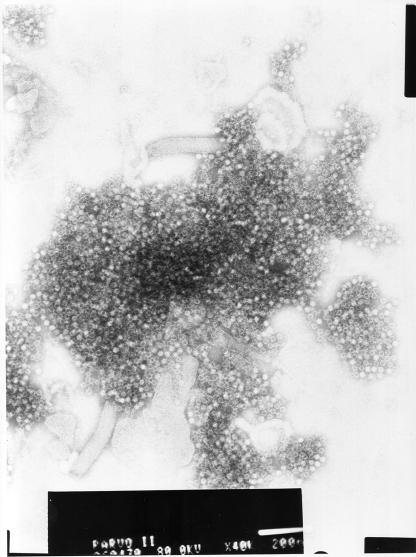

Electron microscopy.

The infected cell paste was studied after negative staining with 2% tungstophosphoric acid, pH 6.0, with a Jeol JEM-100 CXII electron microscope.

CIE.

The “gold standard,” which is CIE performed using a commercial antigen (Antigen Laboratory of the Research Foundation of the Danish Fur Breeders' Association, Glostrup, Denmark) by following the manufacturer's instructions, was tested in parallel with CIE performed using recombinant AMDV VP2 antigen (n = 209) and AMDV VP2 ELISA (n = 316). The same CIE procedure was used for both antigens. Before the recombinant antigen was used in CIE, it was diluted 1:16 in PBS containing 0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). Bromophenol blue (50 μg/ml; Merck Chemicals, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to help the visualization of the antigen on the agarose gel.

AMDV VP2 ELISA.

For all the ELISA procedures, 96-well Nunc immunoplates (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) and 100-μl volumes of reagents were used. All serum and reagent dilutions were done in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.5% BSA, all washes were done twice with PBS-T (PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20), and all incubations were done at RT. Plates were coated with the purified recombinant AMDV VP2 antigen diluted 1:1,500 in 50 mM NaHCO3 buffer (pH 9.6). After incubation o/n, the plates were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h. Serum samples were diluted (1:200), added in duplicate, and incubated for 1 h. The plates were washed and incubated for 1 h with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-cat IgG (diluted according to the manufacturer's instructions) and washed. The substrate reaction with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl benzidine (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was stopped with 0.5 M H2SO4 after 15 min, and the optical density (OD) values were read with a Multiscan EX spectrophotometer (Thermo Labsystems, Vantaa, Finland) at 450 nm. The mean OD for each sample was calculated. The mean OD for two blank wells (containing all reagents except serum) was subtracted from each result. Reference sera (negative, low-positive, and positive) were run every time the assay was carried out. The assay cutoff was determined by counting the mean OD value of the CIE-negative samples (n = 211) plus 1 standard deviation (SD). In total, 316 serum samples (105 positive and 211 negative as determined by CIE) were studied with both ELISA and CIE (commercial antigen).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The VP2 nucleotide sequence of the Finnish AMDV strain C8 was deposited in GenBank under accession number GQ336866.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of recombinant AMDV VP2 protein.

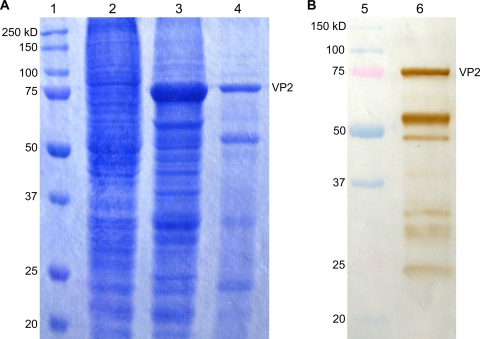

The AMDV VP2 capsid gene, comprising nucleotides 2406 to 4349 of the full-length genome, was amplified by PCR directly from an infected mink and cloned into the baculovirus expression vector pAcYML1. The sequence and reading frame of the VP2 gene were confirmed by DNA sequencing of the recombinant plasmid used for subcloning. The insert had the highest nucleotide (98%) and amino acid (97%) identities with AMDV-G (GenBank accession no. M20036) (8) and -SL3 (GenBank accession no. X97629) (30) (BLAST search [http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi]). The AMDV VP2 protein was extracted and purified from the cell paste by heating and centrifugation. SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of the purified recombinant protein revealed a protein band corresponding to the expected size of the AMDV VP2 protein (75 kDa) (Fig. 1). The identity of the recombinant AMDV VP2 protein was further confirmed by a Western blot analysis (Fig. 1). In electron microscopy, the recombinant VP2 proteins spontaneously formed empty VLPs, 23 to 25 nm in diameter, with a size and ultrastructure typical of a parvovirus virion (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE gel (A) and Western blot (B) of recombinant AMDV VP2 protein with sera from ADMV antibody-positive mink. Lanes: 1 and 5, molecular-mass marker; 2, S. frugiperda 9 cells; 3, recombinant baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells; 4, purified recombinant antigen; 6, Western blot of the purified recombinant antigen.

FIG. 2.

Negative-stain electron micrograph of recombinant AMDV VP2 VLPs. The white bar at the bottom indicates 200 nm.

Evaluation of recombinant antigen in comparison with the commercially available antigen in CIE.

A serum panel (n = 209) was studied with CIE using both the recombinant antigen and the commercially available antigen, with 100 AMDV antibody-positive and 109 negative samples. CIE performed with the recombinant antigen had a sensitivity and specificity of 100% (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison between detection of AMDV antibodies by CIE (commercial antigen) and that by CIE (recombinant antigen) and ELISA

| Assay and result | No. of samples with indicated result by CIE (commercial antigen)

|

Correlation (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| ELISA | 98 | 99 | 97 | ||

| Positive | 104 | 6 | |||

| Negative | 1 | 205 | |||

| CIE (recombinant antigen) | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Positive | 100 | 0 | |||

| Negative | 0 | 109 | |||

Evaluation of ELISA in comparison with CIE.

Three hundred sixteen serum samples all together were studied with both ELISA and CIE (commercial antigen). Two hundred eleven of the samples were negative and 105 positive by CIE; 206 were negative and 110 positive by ELISA. ELISA had a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 97% if CIE performed with a commercial antigen was considered a “gold standard” method (Table 1). The cutoff was 0.099 + 0.127, or 0.255. The ODs of the samples obtained by ELISA are shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Graph of the ELISA samples. The x axis shows the number of samples and the y axis the OD of the samples as obtained by ELISA.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to develop an ELISA method based on recombinant antigen for detecting anti-AMDV antibodies in minks. We cloned the full-length VP2 gene, expressed the protein in a baculovirus system, and demonstrated that VLPs formed spontaneously. Using the purified recombinant VP2 capsids as an antigen, we developed a direct IgG ELISA for studying mink sera. We evaluated the AMDV VP2 ELISA and CIE using the purified recombinant antigen in parallel with CIE using a commercially available traditional antigen.

Different field strains of AMDV exhibit a considerable degree of genetic variability (8, 18, 21, 25). The ELISA described here could identify sera from minks infected with AMDV from different genogroups as positive, indicating that this assay should detect antibody-positive minks infected by any AMDV strain.

The expression of AMDV VP2 protein in the baculovirus system enables the production of large quantities of conformationally optimal antigen for diagnostic use. The results showed that the recombinant protein has a good antigenicity and can be used in both CIE and ELISA. Also, the results from both assays were in good concordance with the commercial CIE results. Previous studies have, however, indicated that the sensitivity of CIE is not very good and that its role as a “gold standard” is questionable (2). It is therefore possible that some of the samples that were positive by ELISA and negative by CIE could actually be true positives, and the ELISA might be even more specific than these results indicate. This is also supported by the fact that four out of six of the ELISA-positive-but-CIE-negative samples had rather high ODs, ranging from 0.641 to 1.249 (Fig. 3).

The results of this study show that in CIE recombinant antigen can replace the traditional antigen and that ELISA is a suitable alternative to CIE for diagnosing AMDV infection in minks. There are, however, a few requirements that need to be met before ELISA can be used for mass screening. Both the introduction of the sample from the glass capillary to the ELISA plate and the dispensing of the various reagents are laborious and time-consuming. Thus, a new method for collecting samples should be created, and the whole assay should be automated. If these requirements can be met, the ELISA has the potential to become an economical, efficient, and accurate test method. The ELISA would then have at least three advantages over CIE. First, it requires less staff, as there are fewer manual steps than in CIE. Second, the results are objective and independent of the experience of the reader, whereas in CIE there is a possibility of false-positive results due to errors in visualizing the results caused by nonspecific precipitation lines. Third, the automated system allows for an increase in the number of tested samples without recruitment of additional staff. For example, in 2008 almost 500,000 serum samples from minks were tested for AMDV antibodies in Finland, and the number is increasing each year, which makes using the traditional CIE test laborious. Thus, there is a need for high-throughput assays, and this study, describing an ELISA based on recombinant VLPs, should be taken as a proof of concept for development of AMDV antibody testing in this direction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation (Tekes) grant 1596/31/05.

We thank Leena Kostamovaara (Haartman Institute) and Majvor Eerola (Fur Animal Feed Laboratory) for excellent technical assistance, Irja Luoto (HUSLAB) for electron micrographs, and Tarja Hinkkanen (Finnish Fur Breeders' Association) for sample collection.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aasted, B., and A. Cohn. 1982. Inhibition of precipitation in counter current electrophoresis. A sensitive method for detection of mink antibodies to Aleutian disease virus. APMIS Sect. C 90:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aasted, B., S. Alexandersen, A. Cohn, and M. Hansen. 1986. Counter current line absorption immunoelectrophoresis in an alternative diagnostic screening test to counter current immunoelectrophoresis in Aleutian disease (AD) eradication programs. Acta Vet. Scand. 27:410-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aasted, B., S. Alexandersen, and J. Christensen. 1998. Vaccination with Aleutian mink disease parvovirus (AMDV) capsid proteins enhances disease, while vaccination with the major non-structural protein causes partial protection from disease. Vaccine 16:1158-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexandersen, S., and J. Hau. 1985. Rocket line immunoelectrophoresis: an improved assay for simultaneous quantification of mink parvovirus (Aleutian disease virus) antigen and antibody. J. Virol. Methods 10:145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexandersen, S., J. Hau, B. Aasted, and O. M. Poulsen. 1985. Thin-layer counter current line absorption immunoelectrophoretic analysis of antigens and antibodies to Aleutian disease virus—a mink parvovirus. Electrophoresis 6:535-538. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexandersen, S. 1990. Pathogenesis of disease caused by Aleutian mink disease parvovirus. Dissertation. The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University of Copenhagen, Denmark. [PubMed]

- 7.Bloom, M. E., R. E. Race, and J. B. Wolfinbarger. 1980. Characterization of Aleutian disease virus as a parvovirus. J. Virol. 35:836-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloom, M. E., S. Alexandersen, S. Perryman, D. Lechner, and J. B. Wolfinbarger. 1988. Nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus (ADV): sequence comparisons between a nonpathogenic and a pathogenic strain of ADV. J. Virol. 62:2903-2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloom, M. E., S. Alexandersen, C. F. Garon, S. Mori, W. Wei, S. Perryman, and J. B. Wolfinbarger. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the 5′-terminal palindrome of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus and construction of an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 64:3551-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloom, M. E., H. Kanno, S. Mori, and J. B. Wolfinbarger. 1994. Aleutian mink disease: puzzles and paradigms. Infect. Agents Dis. 3:279-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castelruiz, Y., M. Blixenkrone-Møller, and B. Aasted. 2005. DNA vaccination with the Aleutian mink disease virus NS1 gene confers partial protection against disease. Vaccine 23:1225-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho, H. J., and D. G. Ingram. 1972. Antigen and antibody in Aleutian disease in mink. I. Prepicitation reaction by agar-gel electrophoresis. J. Immunol. 108:555-557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen, J., T. Storgaard, B. Bloch, S. Alexandersen, and B. Aasted. 1993. Expression of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus proteins in a baculovirus vector system. J. Virol. 67:229-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemens, D. L., J. B. Wolfinbarger, S. Mori, B. D. Berry, S. F. Hayes, and M. E. Bloom. 1992. Expression of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus capsid proteins by a recombinant vaccinia virus: self-assembly of capsid proteins into particles. J. Virol. 66:3077-3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crawford, T. B., T. C. McGuire, D. D. Porter, and J. Cho. 1977. A comparative study of detection methods for Aleutian disease viral antibody. J. Immunol. 118:1249-1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fournier-Chambrillon, C., B. Aasted, A. Perrot, D. Pontier, F. Sauvage, M. Artois, J.-M. Cassiède, X. Chauby, A. Dal Molin, C. Simon, and P. Fournier. 2004. Antibodies to Aleutian mink disease parvovirus in free-ranging European mink (Mustela lutreola) and other small carnivores from southwestern France. J. Wildl. Dis. 40:394-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorham, J. R., J. B. Henson, T. B. Crawford, and G. A. Padgett. 1976. The epizootiology of Aleutian disease, p. 135-158. In R. H. Kimberlain (ed.), Slow virus diseases of animals and man. Frontiers of Biology, North-Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [PubMed]

- 18.Gottschalck, E., S. Alexandersen, T. Storgaard, M. E. Bloom, and B. Aasted. 1994. Sequence comparison of the non-structural genes of four different types of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus indicates an unusual degree of variability. Arch. Virol. 138:213-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadlow, W. J., R. E. Race, and R. C. Kennedy. 1983. Comparative pathogenicity of four strains of Aleutian disease virus for pastel and sapphire mink. Infect. Immun. 41:1016-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenyon, A. J., B. J. Kenyon, and E. C. Hahn. 1978. Protides of the Mustelidae: immunoresponse of mustelids to Aleutian mink disease virus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 39:1011-1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knuuttila, A., N. Uzcátegui, J. Kankkonen, O. Vapalahti, and P. Kinnunen. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of Aleutian mink disease virus in Finland. Vet. Microbiol. 133:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mañas, S., J. C. Ceña, J. Ruiz-Olmo, S. Palazón, M. Domingo, J. B. Wolfinbarger, and M. E. Bloom. 2001. Aleutian mink disease parvovirus in wild riparian carnivores in Spain. J. Wildl. Dis. 37:138-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuura, Y., R. D. Possee, H. A. Overton, and D. H. Bishop. 1987. Baculovirus expression vectors: the requirements for high level expression of proteins, including glycoproteins. J. Gen. Virol. 68:1233-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oie, K. L., G. Durrant, J. B. Wolfinbarger, D. Martin, F. Costello, S. Perryman, D. Hogan, W. J. Hadlow, and M. E. Bloom. 1996. The relationship between capsid protein (VP2) sequence and pathogenicity of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus (ADV): a possible role for raccoons in the transmission of ADV infections. J. Virol. 70:852-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olofsson, A., C. Mittelholzer, L. Treiberg Berndtsson, L. Lind, T. Mejerland, and S. Belak. 1999. Unusual, high genetic diversity of Aleutian mink disease virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:4145-4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter, D. D., A. E. Larsen, and H. G. Porter. 1972. The pathogenesis of Aleutian disease of mink. II. Enhancement of tissue lesions following the administration of a killed virus vaccine or passive antibody. J. Immunol. 109:1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter, D. D., A. E. Larsen, and H. G. Porter. 1980. Aleutian disease of mink. Adv. Immunol. 29:261-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porter, H. G., D. D. Porter, and A. E. Larsen. 1982. Aleutian disease in ferrets. Infect. Immun. 36:379-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu, J., F. Cheng, L. R. Burger, and D. Pintel. 2006. The transcription profile Aleutian mink disease parvovirus in CRFK cells is generated by alternative processing of pre-mRNAs produced from a single promoter. J. Virol. 80:654-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuierer, S., M. E. Bloom, O. R. Kaaden, and U. Truyen. 1997. Sequence analysis of the lymphotropic Aleutian disease parvovirus ADV-SL3. Arch. Virol. 142:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sico, C., S. White, E. Tsao, and A. Varma. 2002. Enhanced kinetic extraction of parvovirus B19 structural proteins. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 80:250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uttenthal, Å. 1992. Screening for antibodies against Aleutian disease virus (ADV) in mink. Elucidation of dubious results by additive counterimmunoelectrophoresis. Appl. Theor. Electrophor. 3:83-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright, P. F., and B. N. Wilkie. 1982. Detection of antibody in Aleutian disease of mink: comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and counterimmunoelectrophoresis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 43:865-868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, W.-H., M. E. Bloom, B. D. Berry, M. J. McGinley, and K. B. Platt. 1994. Expression of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus capsid proteins in a baculovirus expression system for potential diagnostic use. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 6:23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng, X. W., Y. P. Hua, and D. Y. Liang. 2007. Prokaryotic expression and detective application of the main antigenic region of VP2 protein of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 47:1088-1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]