Abstract

Attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine strain SL3261 was used as an antigen delivery system for the oral immunization of mice against two Cryptosporidium parvum antigens, Cp23 and Cp40. Each antigen was subcloned into the pTECH1 vector system, which allows them to be expressed as fusion proteins with highly immunogenic fragment C of tetanus toxin under the control of the anaerobically inducible nirB promoter. The recombinant vector was introduced into Salmonella Typhimurium vaccine strain SL3261, and the stable soluble expression of the chimeric protein was evaluated and confirmed by Western blotting with polyclonal C. parvum antisera. Mice were inoculated orally with a single dose of SL3261/pTECH-Cp23 or Cp40, respectively, and plasmid stability was demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo. Specific serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against the Cp23 or Cp40 antigen were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay 35 days after immunization. Also, serum IgA and mucosal (feces) IgA antibodies were detected in 30% of the mice immunized with Cp23. In addition, prime-boosting with Cp23 and Cp40 DNA vaccine vectors followed by Salmonella immunization significantly increased antibody responses to both antigens. Our data show that a single oral inoculation with recombinant S. Typhimurium SL3261 can induce specific antibody responses to the Cp23 or Cp40 antigen from C. parvum in mice, suggesting that recombinant Salmonella is a feasible delivery system for a vaccine against C. parvum infection.

Cryptosporidium parvum is an obligate intracellular parasite that infects intestinal epithelial cells and has been identified as being a significant cause of diarrheal disease in a variety of mammalian species including rodents, livestock, and humans (24). Infection is usually self-limiting in immunocompetent individuals but can be severe and even life-threatening for those that have compromised immune systems, such as human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals, transplant recipients, children, and the elderly (30). The incidence of cryptosporidiosis has been reported to be in the range of 1 to 10% (34) but has been reported to be as high as 30% in children in India and Saudi Arabia (1, 10, 14). In light of the fact that chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of infections of immunodeficient individuals are limited and not always efficacious, the development of a vaccine that is capable of inducing at least partial protection would be beneficial to specific high-risk populations. Data from human volunteer studies have suggested that at least partial immunity develops, as subsequent exposures with the parasite resulted in less-severe clinical signs (26).

Since all life cycle stages occur in the host epithelium, the mucosal immune response is paramount to providing resistance and protection. The use of live oral Salmonella vaccines has been successful at delivering heterologous antigens and at generating a mucosal immune response against a number of organisms including intestinal parasitic species such as Toxoplasma gondii and Eimeria tenella (18, 29). Advantages of attenuated Salmonella vaccines include the fact that they induce both cell-mediated and humoral responses, elicit a systemic and local response, are easy to administer, and are affordable (13). To date, reports of the use of attenuated Salmonella as a vaccine vector in C. parvum are not available. Through this study, we assessed the use of an attenuated Salmonella strain carrying specific C. parvum antigens as a vaccine vector and the potential that it offers against C. parvum infection.

In this study, we compared the abilities of attenuated strains of Salmonella to express the immunodominant antigens Cp23 and Cp40. These surface antigens of C. parvum are considered to be immunodominant since they are recognized by serum antibodies of humans and many other animals (25, 31, 36). Moreover, the level of oocyst secretion was reduced following the administration of colostrum directed against the Cp23 antigen (26). T-cell responses to Cp23 from infected mice (3), calves (36), and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (33) with C. parvum infection have been reported, indicating its role in the immune response to C. parvum. Recombinant Cp40 antigen was previously shown to generate a T-cell proliferation response in mice (31). Also, monoclonal antibodies against Cp40 antigen have been shown to neutralize C. parvum infection and inhibit attachment in vitro (4). We also report the safety and plasmid stability of the Salmonella vaccine vector in mice as well as the ability to induce an antibody response against the expressed antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Initial cloning was done using Escherichia coli Top10 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 (aroA r+ m+) and S. Typhimurium LB5010 (galE r− m+) were obtained from the Salmonella Genetic Stock Center (University of Calgary, Canada). S. Typhimurium strain SL5338/pTECH1 was supplied by K. Turner (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, United Kingdom). Bacteria were cultured at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) when appropriate. E. coli strain BL21/pGEX-4T-Cp23 was kindly provided by J. Priest (CDC, Atlanta, GA).

Animals.

Six- to eight-week-old male and female C57BL/6 interleukin-18 knockout (IL-18KO) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), bred, and housed at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Decatur, GA) animal facility. Animals were fed sterile food and water and kept in HEPA-filtered barrier-isolated facilities. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine before DNA immunizations and bleeding procedures. All manipulations were performed within HEPA-filtered biological containment hoods.

Construction of expression plasmids pTECH1-Cp23 and pTECH1-Cp40.

pTECH1 plasmid DNA was purified from strain SL5338/pTECH1. Plasmid pTECH1 was then transformed into E. coli Top10 cells for further manipulation. The Cp23 and Cp40 genes were amplified by PCR using plasmids pUMVC4b-Cp23 and pUMVC4b-Cp40 (our laboratory) as a template, respectively. The Cp23 gene was amplified with forward primer 5′-CGCTCTAGAATGGGTTGTTCATCATCAAAGCCAGAAACTAAAGTT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCGGGATCCTTAGGCATCAGCTGGCTTGTCTTGT-3′, and the Cp40 gene was amplified with forward primer 5′-CGCTCTAGAGATGTTCCTGTTGAGGGTTCATCATCG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCGGGATCCTTACTCTGAGAGTGATCTTCT-3′. Primers were designed to include XbaI and BamHI restriction sites (underlined), respectively. PCR products were digested with XbaI and BamHI and then ligated into pTECH1, which had been previously digested with the same enzymes. The ligation mix was then transformed into competent Top10 cells, and transformants were selected on LB agar containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Positive clones were confirmed by restriction digestion and sequencing. The constructs were named pTECH1-Cp23 and pTECH1-Cp40, respectively. Plasmid DNA purified from E. coli was first modified by transformation into strain LB5010 to increase electroporation efficiency and then transformed into vaccine strain SL3261.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Expression of the TetC-Cp23 and TetC-Cp40 fusions was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting. Cells were cultured overnight under aerobic conditions and harvested by centrifugation. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and analyzed on a 4 to 20% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and allowed to react with mouse polyclonal C. parvum antiserum. The blots were then probed with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)-horseradish peroxidase (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) and developed using 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) membrane peroxidase substrate.

Immunizations.

For oral immunization, bacteria were grown with aeration overnight, centrifuged, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Eight mice per group received 5 × 109 CFU/mouse of vaccine strain SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 or SL3261/pTECH1-Cp40 or vector control in 0.2 ml PBS intragastrically via gavage needle. For “prime-boost” immunization, 100 μg of DNA vaccine vectors pUMVC4b-Cp23 (8) and pUMVC4b-Cp40 (our laboratory) was injected subcutaneously in the ear on days 0 and 14, followed by oral Salmonella immunization. The inoculum doses were checked by viable counts on LB agar containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Blood samples were collected from the retroorbital plexus or submandibular vein at baseline and 7 weeks postimmunization. Sera were obtained from each blood sample by standard centrifugation, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C until analyzed for antibody levels. Fecal samples were collected on days 0, 18, and 34 postimmunization, homogenized in PBS-Tween, and stored at −20°C until assayed.

Plasmid stability and Salmonella persistence in vivo.

Plasmid persistence was determined in vitro by culturing the bacteria for approximately 100 generations (5 days) without antibiotic selection. The stability of the plasmid was determined by the ratio of the number of cells containing the plasmid (i.e., bacterial colony counts on antibiotic-containing medium) to the total number of cells (viable count on antibiotic-free medium). For plasmid stability in vivo and to determine the bacterial colonization of organs, two mice were euthanized on days 3, 10, and 25 postimmunization, and spleens, livers, and intestinal tracts were collected and homogenized in PBS, respectively. The bacterial counts were determined by plating serial dilutions of the homogenized samples onto xylose lysine deoxycholate agar followed by replica plating onto LB agar with or without ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Bacteria were picked randomly from LB agar plates containing ampicillin for PCR identification and to confirm stable protein expression (data not shown).

Measurement of antibody response by ELISA.

Serum IgA and IgG and fecal IgA antibody responses specific to highly purified recombinant Cp23 and serum IgA and IgG responses to recombinant Cp40 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (27, 31). Briefly, flat-bottomed 96-well Immunlon 2 ELISA plates were coated with 0.2 μg/ml of recombinant Cp23 or recombinant Cp40 in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 50 μl per well and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were blocked with PBS containing 0.3% Tween 20 for 1 h at 4°C. Individual serum samples and pooled fecal samples were diluted 1:100 and 1:25, respectively, in 0.05% Tween 20-PBS, applied onto the wells in duplicate, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After the plates were washed, bound antibodies were detected by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with biotin-labeled conjugate goat anti-mouse IgG, IgA diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-Tween, and IgG1 and IgG2a (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL) diluted 1:800. The plates were washed and incubated for 30 min with a 1:500 dilution of peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (KPL) and developed using the TMB microwell system (KPL). The optical density (OD) at 450 nm was measured by use of an ELISA reader.

Assay of invasion blocking.

An in vitro evaluation to examine the inhibition of sporozoite invasion was performed as described previously (2). Purified oocysts (IOWA isolate) were washed free of 2.5% aqueous potassium dichromate (a storage buffer) with PBS (pH 7.4). Oocysts were then resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium base with 0.75% sodium taurocholate and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Excysted oocysts (predominantly sporozoites) were washed twice in PBS and counted. Sporozoites were then preincubated with a 1:3 dilution of sera from preimmune, immunized, or experimentally infected mice or monoclonal antibody control for 30 min at 37°C; washed; and inoculated onto HTC-8 cells. Culture medium was changed 3 h later to remove free sporozoites. Cells were fixed at 48 h postinfection and labeled with anticryptosporidial antibody as previously described (23). Briefly, cell culture wells were fixed with Bouin's solution for 60 min, decolorized with 70% ethanol, blocked with 0.5% (vol/vol) bovine serum albumin in PBS, and incubated with an anti-C. parvum fluorescein-labeled monoclonal antibody (C3C3-fluorescein isothiocyanate). The numbers of intracellular parasites were counted in a blinded fashion at a ×400 magnification over 50 different fields. Parasite infection was scored from 0 to 5+ according to parasite load. Scoring was as follows: 0, no intracellular stages observed; 1+, 1 to 50 parasites per field; 2+, 50 to 99 parasites per field; 3+, 100 to 150 parasites per field; 4+, 150 to 200 parasites per field; 5+, >200 parasites per field. The data are presented as average parasite scores per well.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations and were analyzed by using analysis of variance. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Expression of Cp23 and Cp40 S. Typhimurium constructs.

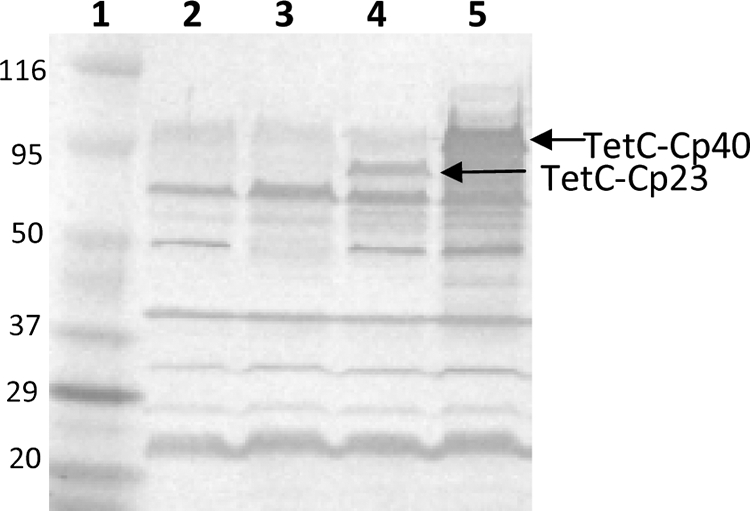

The Cp23 and Cp40 genes from C. parvum were obtained by PCR and subcloned into vector pTECH1. Subcloning into vector pTECH1 yielded constructs that were expected to express the C. parvum antigens fused to the nontoxic but highly immunogenic TetC polypeptide. Both pTECH1-Cp23 and pTECH1-Cp40 constructs were transformed into Salmonella vaccine strain SL3261, and the expression of the fusion proteins was tested. Both aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions induced similar levels of expression of the two constructs (data not shown). The expression of the TetC-Cp23 and TetC-Cp40 fusion proteins from aerobically grown bacterial cells was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with mouse anti-C. parvum serum. Both fusion proteins were stably expressed in a number of different genetic backgrounds, including E. coli (Top10), S. Typhimurium LB5010 (data not shown), and vaccine strain SL3261, and remained soluble. As shown in Fig. 1, anti-C. parvum serum recognizes the full-length fusion proteins in SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 and SL3261-pTECH1-Cp40 lysates. The apparent molecular masses of 75.0 and 95.0 kDa correspond to the TetC-Cp23 and TetC-Cp40 fusion proteins, respectively (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 5).

FIG. 1.

Western blot of bacterial lysates probed with mouse anti-C. parvum polyclonal sera. Lane 1, molecular mass markers (kDa); lane 2, SL3261; lane 3, SL3261/pTECH1; lane 4, SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23; lane 5, SL3261/pTECH1-Cp40.

Plasmid stability and Salmonella persistence in vivo.

The stability of the plasmid during the growth of S. Typhimurium SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 in vitro in medium with or without antibiotic selection was assessed to investigate the effect of an antibiotic-free environment on plasmid segregation. SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 was passaged in antibiotic-free medium for a period of 5 days (approximately 100 generations), and plasmid pTECH1-Cp23 was stably maintained (over 99%) when plated onto medium with or without antibiotics. In order to determine if in vitro stability translated into in vivo stability, three groups of mice (n = 2) were inoculated orally with 3 × 109 CFU/mouse of SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 and euthanatized at days 3, 10, and 25 postimmunization. Table 1 shows the group average bacterial counts per time point performed on homogenates of spleen, liver, and intestines. These data showed that the recombinant construct grew and persisted in the reticuloendothelial system. Also, 100 and 85% of the plasmid were stably maintained as determined by viable counts of SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 on medium with and without ampicillin on days 10 and 25 postinfection, respectively. Furthermore, PCR identification and stable protein expression were determined using randomly selected colonies, indicating that the construct was not being lost in vivo (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 organ colonizationa

| Day postimmunization | CFU

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | Liver | Intestine | |

| 3 | 2.1 × 102 | 12.5 | 4.1 × 102 |

| 10 | 5.6 × 103 | 5.7 × 103 | 7.7 × 103 |

| 25 | 2.5 × 103 | 3.8 × 102 | 5.8 × 102 |

Data are presented as the average CFU obtained from two mice per time point.

Immunogenicity of Salmonella-delivered Cp23 and Cp40 antigens.

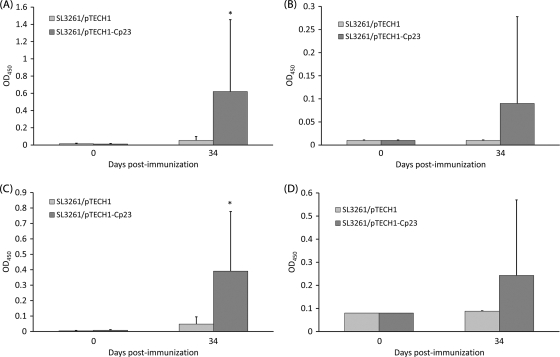

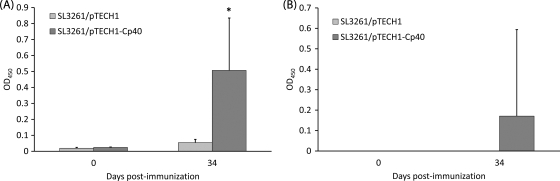

To test the immunogenicity of Salmonella-delivered Cp23 and Cp40 antigens, eight C57BL/6 IL-18KO mice per group were orally immunized with 5 × 109 CFU/mouse of SL3261/pTECH1, SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23, and SL3261/pTECH1-Cp40. Cp23-specific (Fig. 2A) and Cp40-specific (Fig. 3A) IgG and IgG1 subclass production was observed in vaccinated mice at 7 weeks postimmunization. Specific serum Cp23 and Cp40 IgG levels were enhanced significantly in mice immunized with SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 and SL3261/pTECH1-Cp40 compared to mice immunized with the SL3261/pTECH1 control vector. Specific serum (Fig. 2C) and mucosal (Fig. 2D) IgA responses were observed for 30% of the mice immunized with the Cp23 construct. While IgA was detected for Cp23, IgA values for Cp40 were not significantly higher than the baseline values. In order to indirectly determine the T-cell helper cell response bias, sera collected from mice at day 35 were further analyzed for the IgG1-to-IgG2 subclass ratio. Oral immunization with SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 (Fig. 2B) and SL3261/pTECH1-Cp40 (Fig. 3B) induced only an IgG1 antibody response; no IgG2a was detected in any of the sera, suggesting that a Th2 type of response was elicited.

FIG. 2.

Antibody responses against recombinant Cp23 as detected by ELISA in mice inoculated orally with either SL3261/pTECH1 or SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23. (A) Serum IgG. (B) Serum IgG1. (C) Serum IgA. (D) Fecal IgA. Results are expressed as average ODs ± standard deviations at days 0 and 34 postimmunization, and significant differences from values for the control group are indicated with an asterisk (P <0.05). OD450, OD at 450 nm.

FIG. 3.

Antibody responses against recombinant Cp40 as detected by ELISA in mice inoculated orally with either SL3261/pTECH1 or SL3261/pTECH1-Cp40. (A) Serum IgG. (B) Serum IgG1. Results are expressed as average ODs ± standard deviations at days 0 and 34 postimmunization, and significant differences from values for the control group are indicated with an asterisk (P < 0.05). OD450, OD at 450 nm.

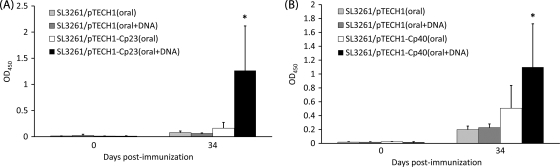

To see if prior immunization with a DNA-vaccine vector could enhance the oral Salmonella vaccination antibody response, C57BL/6 IL-18KO mice were immunized with 100 μg of either pUMVC4b (control vector) or the recombinant DNA-vaccine vectors pUMVC4b-Cp23 or pUMVC4b-Cp40 at 2-week intervals, followed by oral Salmonella immunization. This resulted in a significant increase in titers of IgG-specific anti-Cp23 (Fig. 4A) and anti-Cp40 (Fig. 4B) antibody responses.

FIG. 4.

Specific serum IgG antibody responses against recombinant Cp23 (A) and recombinant Cp40 (B) as detected by ELISA for mice inoculated orally or “prime-boost”-immunized mice. “Prime-boost”-immunized mice were administered 2 doses (over 2 weeks) of a Cp23 or Cp40 DNA vaccine followed by oral immunization with recombinant Salmonella. Results are expressed as average ODs ± standard deviations at days 0 and 34 postimmunization, and significant differences between “prime-boost”-immunized mice (DNA plus oral vaccine) and mice immunized orally are indicated with an asterisk (P < 0.05). OD450, OD at 450 nm.

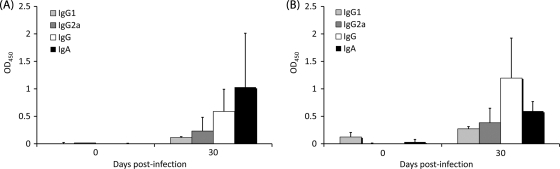

To compare antibody responses of mice naturally infected with C. parvum, C57BL/6 IL-18KO mice were inoculated with 1,000 oocysts and allowed to recover. The Cp23-specific (Fig. 5A) and Cp40-specific (Fig. 5B) responses were measured at 0 and 30 days postinfection. Both IgG and IgA responses to both antigens were observed. IgG titers for infected mice were lower than titers for immunized mice. The IgG2b subclass was predominant in infected mice. In addition, IgA titers were notable in infected mice and substantially higher than those in mice immunized with Cp40.

FIG. 5.

Antibody responses (serum IgG, IgG1, IgG2b, and IgA) against recombinant Cp23 (A) or recombinant Cp40 (B) as detected by ELISA for mice infected with C. parvum and allowed to recover. Results are expressed as average ODs ± standard deviations at days 0 and 30 postimmunization. OD450, OD at 450 nm.

In vitro detection of neutralizing antibodies.

To determine if antibody from orally immunized mice could inhibit the parasite from infecting HCT-8 host cells, sera from immunized mice were incubated with sporozoites and analyzed for their ability to block infection. Sera from mice immunized with SL3261/pTECH1-Cp23 and -Cp40 were individually able to reduce infection by sporozoites by 30% (at a 1:3 dilution), which was comparable to that of a monoclonal antibody directed against Cp23. The mean infection scores (± standard deviations) for treatments with Cp23, Cp40, and a medium control were 2.57 ± 1.4 (29.0% inhibition; P = 0.00005), 2.70 ± 1.2 (23.0% inhibition; P = 0.001), and 3.53 ± 1.5, respectively. Preimmune sera and sera from experimentally infected mice were also tested at the same dilution, and no significant difference in parasite growth compared to the positive control was observed (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we demonstrated that the delivery of a Cp23 DNA-vaccine vector subcutaneously into the ears of mice could induce a sustainable antigen-specific immune response characterized by significant levels of specific antibody and cellular responses compared to those of control animals as well as partial protection against C. parvum infection (8). However, we found no detectable level of IgA in sera of immunized mice, suggesting that while a systemic response was generated, mucosal immunity may be limited or lacking. In recent years, there has been significant progress in the development of multivalent vaccines using attenuated Salmonella as a vaccine vector. Attenuated Salmonella has been used to express a number of antigens from bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotic parasites with variable results, ranging from an unstable expression of the recombinant antigen to the production of successful experimental vaccines capable of generating protective immune responses (5). Since Salmonella vaccine vectors have been useful to generate cellular, humoral, and secretory immune responses to recombinant guest antigens, we utilized the pTECH1 (15) vector system to express the immunodominant Cp23 and Cp40 antigens from C. parvum in the SL3261 Salmonella vaccine strain. Salmonella vaccine strain SL3261 (11) contains a mutation in the aromatic amino biosynthetic pathway and was previously reported to be among the safest vaccine strains (22). Our analysis revealed the stable and soluble expression of both Cp23 and Cp40 fusion proteins in strain SL3261 as shown by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The expression of both fusion proteins is regulated by the anaerobically induced nirB promoter. However, protein expression levels were similar when either aerobic or anaerobic growth conditions were used. The fusion partner TetC may also play a role in the stable expression of the fusion proteins, as it was previously described to stabilize the expression of heterologous proteins in Salmonella strain SL3261 (16).

C57BL/6 interleukin-12p40−/− mice, used for DNA vaccine work in our laboratory, are generally too susceptible to Salmonella infection, even with attenuated strains, to tolerate the high doses needed for effective inoculation (19, 21). We therefore opted to use an alternative mouse model, C57BL/6 IL-18KO background, previously used in this laboratory (7). It offers a number of advantages essential for immunological studies such as a high level of susceptibility to C. parvum infection, resolution of the infection, resistance to reinfection, and development of a mixed Th1/Th2 mucosal cytokine response (6, 7). The test mice displayed signs of malaise during the first week but quickly recovered without any other side effects throughout the experiment. By week 7 postimmunization, Salmonella infection had cleared, as no recombinant bacteria were detected in mouse organs or feces (data not shown). Viable recombinant bacteria were isolated from spleen, liver, and intestines on days 3, 10, and 25 postimmunization, indicating the in vivo stability of the recombinant strain. We also observed a stable expression of the fusion proteins under antibiotic-free conditions over a period of 5 days. Efficient clearance and both in vivo and in vitro stability suggest the safety and suitability of this particular vaccine vector for the delivery of C. parvum antigens in mice.

Our study shows that a single oral inoculation with Salmonella vaccine strain SL3261 expressing Cp23 and Cp40 is able to generate a specific humoral and mucosal response in mice. Significantly elevated levels of IgG were demonstrated in the sera of both Cp23- and Cp40-immunized mice. The predominant response was IgG1, suggesting a Th2 bias. Immunization of recombinant Salmonella-primed mice was reported to shift the T-helper response to a Th2 bias (12). In contrast, both Th1 and Th2 IgG subtypes from C. parvum-infected mice were observed. We also observed specific serum IgA and mucosal IgA (feces) in mice immunized with Cp23 but not in mice immunized with the Cp40 construct. However, these titers were not as high as those generated in mice orally infected with C. parvum. The establishment of a mucosal response appears to be essential for providing resistance and protection to C. parvum, since the parasite life cycle takes place in the gut mucosa. In order to achieve the optimal response from an oral vaccine only, alternative strategies may be needed. The use of vaccine systems that deliver antigens to the periplasmic space or surface of the bacteria may result in more appropriate antigen presentation and processing, eliciting a greater immune response (9).

We also evaluated a “prime-boost” strategy, where each antigen was administered as a DNA vaccine followed by oral immunization with a recombinant Salmonella strain. The “prime-boost” strategy may be an ideal approach since DNA vaccines drive a cell-mediated response, and the Salmonella vaccine offers a way of generating a localized mucosal response. Studies have shown that heterologous or homologous “prime-boost” regimens using S. enterica serovar Typhi in primed mice can enhance the serum antibody response (20, 35). Our results show that the sequential administration of the same antigen in two different vaccine formulations by different routes was far more immunogenic, significantly boosting Cp23 and Cp40 serum IgG levels. We also evaluated Salmonella vaccine strain SK100 (17) expressing Cp23 antigen in immunized mice. In addition to the aroA mutation, this strain has a mutation in the waaN gene, a gene that encodes a myristyl transferase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of lipid A. It was previously reported that this attenuated strain enhanced immune responses against the malaria circumsporozoite protein compared to the immune response of its isogenic parent (SL3261) (22). However, no significant differences in antibody response were detected in mice immunized with SK100 (SL3261waaN) and SL3261 expressing the Cp23 antigen (data not shown). We also confirmed the ability of Cp23 and Cp40 immune sera to block infection in vitro, as both immune sera were individually able to partially inhibit C. parvum sporozoite infection of HCT-8 cells. However, the reduction of infection exceeded that of immune sera from infected mice, perhaps indicating differences in antibody avidity or epitope targeting. Further studies may elucidate the functional differences between specific DNA immunization and responses resulting from natural or experimental infections.

Our results demonstrate the immunogenicity of a single oral immunization with Salmonella vaccine strain SL3261 expressing recombinant C. parvum antigens in mice. Furthermore, we established the stability and safety of the recombinant Salmonella vector. A partial inhibition of infection by sporozoites with immune sera was also demonstrated. The use of a Salmonella vaccine vector to deliver C. parvum antigens is a feasible way to elicit humoral and mucosal responses in the immunized host but will require further optimization. Nevertheless, this vector system represents a useful tool in studies evaluating effective immunization strategies against C. parvum infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Arrowood (CDC, Atlanta, GA) and his technical staff for the production and purification of oocysts.

This work was supported, in part, by grant R01-AI-36680 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Medical Research Service, U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The procedures used in the experiments reported in this paper comply with the laws governing research with animals in the United States of America.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Braiken, F. A., A. Amin, N. J. Beeching, M. Hommel, and C. A. Hart. 2003. Detection of Cryptosporidium amongst diarrhoeic and asymptomatic children in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 97:505-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrowood, M. J., J. R. Mead, L. Xie, and X. You. 1996. In vitro anticryptosporidial activity of dinitroaniline herbicides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 136:245-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonafonte, M. T., L. M. Smith, and J. R. Mead. 2000. A 23kDa antigen of Cryptosporidium parvum induces a cellular immune response on in vitro stimulated spleen and mesenteric lymph node cells from infected mice. Exp. Parasitol. 96:32-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cevallos, A. M., N. Bhat, R. Verdon, D. H. Hamer, B. Stein, S. Tzipori, M. E. Pereira, G. T. Keusch, and H. D. Ward. 2000. Mediation of Cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro by mucin-like glycoproteins defined by a neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 68:5167-5175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatfield, S. N., M. Roberts, G. Dougan, C. Hormaeche, and C. M. Khan. 1995. The development of oral vaccines against parasitic diseases utilizing live attenuated Salmonella. Parasitology 110(Suppl.):S17-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehigiator, H. N., N. McNair, and J. R. Mead. 2003. IL-12 knockout C57BL/6 mice are protected from re-infection with Cryptosporidium parvum after challenge. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 50:(Suppl.):539-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehigiator, H. N., P. Romagnoli, K. Borgelt, M. Fernandez, N. McNair, W. E. Secor, and J. R. Mead. 2005. Mucosal cytokine and antigen-specific responses to Cryptosporidium parvum in IL-12p40 KO mice. Parasite Immunol. 27:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehigiator, H. N., P. Romagnoli, J. W. Priest, W. E. Secor, and J. R. Mead. 2007. Induction of murine immune responses by DNA encoding a 23-kDa antigen of Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasitol. Res. 101:943-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galen, J. E., M. F. Pasetti, S. Tennant, P. Ruiz-Olvera, M. B. Sztein, and M. M. Levine. 2009. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi live vector vaccines finally come of age. Immunol. Cell Biol. 5:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta, S., S. Narang, V. Nunavath, and S. Singh. 2008. Chronic diarrhoea in HIV patients: prevalence of coccidian parasites. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 26:172-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jespersgaard, C., P. Zhang, G. Hajishengallis, M. W. Russell, and M. W. Michalek. 2001. Effect of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium expressing a Streptococcus mutans antigen on secondary responses to the cloned protein. Infect. Immun. 69:6604-6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang, H. Y., J. Srinivasan, and R. Curtiss III. 2002. Immune responses to recombinant pneumococcal PspA antigen delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine. Infect. Immun. 70:1739-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur, R., D. Rawat, M. Kakkar, B. Uppal, and V. K. Sharma. 2002. Intestinal parasites in children with diarrhea in Delhi, India. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 33:725-729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan, C. M., B. Villarreal-Ramos, R. J. Pierce, G. Riveau, R. Demarco de Hormaeche, H. McNeill, T. Ali, N. Fairweather, S. Chatfield, A. Capron, et al. 1994. Construction, expression, and immunogenicity of the Schistosoma mansoni P28 glutathione S-transferase as a genetic fusion to tetanus toxin fragment C in a live Aro attenuated vaccine strain of Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11261-11265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan, C. M., B. Villarreal-Ramos, R. J. Pierce, R. Demarco de Hormaeche, H. McNeill, T. Ali, S. Chatfield, A. Capron, G. Dougan, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1994. Construction, expression, and immunogenicity of multiple tandem copies of the Schistosoma mansoni peptide 115-131 of the P28 glutathione S-transferase expressed as C-terminal fusions to tetanus toxin fragment C in a live aro-attenuated vaccine strain of Salmonella. J. Immunol. 153:5634-5642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan, S. A., P. Everest, S. Servos, N. Foxwell, U. Zähringer, H. Brade, E. T. Rietschel, G. Dougan, I. G. Charles, and D. J. Maskell. 1998. A lethal role for lipid A in Salmonella infections. Mol. Microbiol. 29:571-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konjufca, V., M. Jenkins, S. Wang, M. D. Juarez-Rodriguez, and R. Curtiss III. 2008. Immunogenicity of recombinant attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine strains carrying a gene that encodes Eimeria tenella antigen SO7. Infect. Immun. 76:5745-5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehmann, J., S. Springer, C. E. Werner, T. Lindner, S. Bellmann, R. K. Straubinger, H. J. Selbitz, and G. Alber. 2006. Immunity induced with a Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis live vaccine is regulated by Th1-cell-dependent cellular and humoral effector mechanisms in susceptible BALB/c mice. Vaccine 24:4779-4793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Londoño-Arcila, P., D. Freeman, H. Kleanthous, A. M. O'Dowd, S. Lewis, A. K. Turner, E. L. Rees, T. J. Tibbitts, J. Greenwood, T. P. Monath, and M. J. Darsley. 2002. Attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi expressing urease effectively immunizes mice against Helicobacter pylori challenge as part of a heterologous mucosal priming-parenteral boosting vaccination regimen. Infect. Immun. 70:5096-5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mastroeni, P., J. A. Harrison, J. H. Robinson, S. Clare, S. Khan, D. J. Maskell, G. Dougan, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1998. Interleukin-12 is required for control of the growth of attenuated aromatic-compound-dependent salmonellae in BALB/c mice: role of gamma interferon and macrophage activation. Infect. Immun. 66:4767-4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKelvie, N. D., S. A. Khan, M. H. Karavolos, D. M. Bulmer, J. J. Lee, R. DeMarco, D. J. Maskell, F. Zavala, C. E. Hormaeche, and C. M. A. Khan. 2008. Genetic detoxification of an aroA Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine strain does not compromise protection against virulent Salmonella and enhances the immune responses towards a protective malarial antigen. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 52:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mead, J., and N. McNair. 2006. Antiparasitic activity of flavonoids and isoflavones against Cryptosporidium parvum and Encephalitozoon intestinalis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 259:153-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mead, J. R., M. J. Arrowood, and C. R. Sterling. 1988. Antigens of Cryptosporidium sporozoites recognized by immune sera of infected animals and humans. J. Parasitol. 74:135-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss, D. M., C. L. Chappell, P. C. Okhuysen, H. L. DuPont, M. J. Arrowood, A. W. Hightower, and P. J. Lammie. 1998. The antibody response to 27-, 17-, and 15-kDa Cryptosporidium antigens following experimental infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 178:827-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okhuysen, P. C., C. L. Chappell, C. R. Sterling, W. Jakubowski, and H. L. DuPont. 1998. Susceptibility and serologic response of healthy adults to reinfection with Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect. Immun. 66:441-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perryman, L. E., S. J. Kapil, M. L. Jones, and E. L. Hunt. 1999. Protection of calves against cryptosporidiosis with immune bovine colostrum induced by a Cryptosporidium parvum recombinant protein. Vaccine 17:2142-2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Priest, J. W., J. P. Kwon, D. M. Moss, J. M. Roberts, M. J. Arrowood, M. S. Dworkin, D. D. Juranek, and P. J. Lammie. 1999. Detection by enzyme immunoassay of serum immunoglobulin G antibodies that recognize specific Cryptosporidium parvum antigen. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1385-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu, D., S. Wang, W. Cai, and A. Du. 2008. Protective effect of a DNA vaccine delivered in attenuated Salmonella typhimurium against Toxoplasma gondii infection in mice. Vaccine 26:4541-4548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadraei, J., M. Rizvi, and U. Baveja. 2005. Diarrhea, CD4+ cell counts and opportunistic protozoa in Indian HIV-infected patients. Parasitol. Res. 97:270-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh, I., C. Theodos, and S. Tzipori. 2005. Recombinant proteins of Cryptosporidium parvum induce proliferation of mesenteric lymph node cells in infected mice. Infect. Immun. 73:5245-5248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, L. M., M. T. Bonafonte, and J. R. Mead. 2000. Cytokine expression and specific lymphocyte proliferation in two strains of Cryptosporidium parvum-infected gamma-interferon knockout mice. J. Parasitol. 86:300-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, L. M., J. W. Priest, P. J. Lammie, and J. R. Mead. 2001. Human T and B cell immunoreactivity to a recombinant 23-kDa Cryptosporidium parvum antigen. J. Parasitol. 87:704-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tzipori, S., and G. Widmer. 2008. A hundred-year retrospective on cryptosporidiosis. Trends Parasitol. 24:184-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vindurampulle, C. J., L. F. Cuberos, E. M. Barry, M. F. Pasetti, and M. M. Levine. 2004. Recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi in a prime-boost strategy. Vaccine 22:3744-3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyatt, C. R., S. Lindahl, K. Austin, S. Kapil, and J. Branch. 2005. Response of T lymphocytes from previously infected calves to recombinant Cryptosporidium parvum p23 vaccine antigen. J. Parasitol. 91:1239-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]