Abstract

Objective

Patients who receive prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV) have high resource utilization and relatively poor outcomes, especially the elderly, and are increasing in number. The economic implications of PMV provision however are uncertain and would be helpful to providers and policymakers. Therefore, we aimed to determine the lifetime societal value of PMV.

Design and Patients

Adopting the perspective of a healthcare payor, we developed a Markov model to determine the cost-effectiveness of providing mechanical ventilation for at least 21 days to a 65 year-old critically ill base-case patient compared to the provision of comfort care resulting in withdrawal of ventilation. Input data were derived from the medical literature, Medicare, and a recent large cohort study of ventilated patients.

Measurements and Main Results

We determined lifetime costs and survival, quality-adjusted life expectancy, and cost-effectiveness as reflected by costs per quality-adjusted life year gained ($ per QALY). Providing PMV to the base-case patient cost $55,460 per life-year gained and $82,411 per QALY gained compared to withdrawal of ventilation. Cost-effectiveness ratios were most sensitive to variation in age, hospital costs, and probability of readmission, though less sensitive to post-acute care facility costs. Specifically, incremental costs per QALY gained by PMV provision exceeded $100,000 with age ≥68 and when predicted one-year mortality was >50%.

Conclusions

The cost-effectiveness of PMV provision varies dramatically based on age and likelihood of poor short- and long-term outcomes. Identifying patients likely to have unfavorable outcomes, lowering intensity of care for appropriate patients, and reducing costly readmissions should be future priorities in improving the value of PMV.

Keywords: Cost-benefit analysis, respiration, artificial, tracheostomy, health, services research, outcome and process assessment (health care)

INTRODUCTION

More than a million persons admitted to US intensive care units (ICUs) receive mechanical ventilation annually, though usually for just a few days. (1) However, nearly 10% of all critically ill patients and up to 34% of those ventilated for more than two days require extended periods of ventilatory support. (2–4) Prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV) is most commonly defined by either ≥21 days of ventilation or 4 or more days of ventilation with placement of a tracheostomy. (5) Presently, there are over 100,000 new PMV cases annually in the US, half of whom are Medicare beneficiaries, though PMV incidence is increasing more rapidly than mechanical ventilation itself. (6, 7)

Unfortunately, PMV patients’ care is expensive and their overall outcomes often poor. (3, 8) In 2005, Medicare-eligible PMV patients ranked third in summative inpatient charges by diagnostic group and first in charges per patient—significantly greater than the resource utilization of persons with sepsis, myocardial infarctions, or gastrointestinal bleeding. (7) These annual expenditures exceeding $20 billion do not include payments for extended stays in the long-term acute care, rehabilitation, and skilled nursing facilities to which more than 80% of PMV patients are discharged. (2) Despite receiving such a high level of care, fewer than 50% of PMV hospital survivors survive more than one year. (2, 9, 10) Those who do survive often suffer significant disability in performing basic daily functions, experience reduced quality of life, and possess significant long-term caregiving needs. (2, 8)

Persons aged 65 and older presently account for over half of all intensive care unit days in the US. (11) However, this age group, whose members also have the highest baseline risk of respiratory failure and subsequent PMV, is expected to double in number between 2000 and 2030 and precipitate a critical care workforce shortage in the process. (6, 12)

In light of the dramatic financial pressures associated with health care costs confronting US society, cost-effectiveness analyses can be particularly valuable tools that enable providers, payors, and policymakers to understand better how to prioritize and target potential interventions within the process of care, optimize resource utilization, and plan for future changes. (13) There have been recent calls within the critical care field for greater attention by both clinicians and policymakers to be given to economic analyses of critical care. (14, 15) Despite the high costs of PMV and often poor outcomes, there have been no formal economic analyses of PMV provision that incorporate either a lifetime time horizon or the contributions of acute as well as post-acute care costs. To address these needs, we analyzed the economic impact of PMV provision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We used decision analysis to compare the lifetime costs and survival of patients who received PMV (mechanical ventilation for ≥21 days with placement of a tracheostomy) to those who received comfort measures only resulting in withdrawal of ventilation (Table 1). Clinical relevance guided the framing of our analyses as we assumed that final decision-making regarding mechanical ventilation continuation or withdrawal would be conducted during ventilator days 7 to 21. This two week decision-making period allowed separation from analyses of those with very severe illness (and thus early death) and approximates similar decision strategies performed among the severely ill. (16) Although this strategy reflects a hypothetical situation and does not specify patients’ preferences for PMV from the time of ICU admission, we believed that it best approximates the experience of physicians, critically ill patients, and families in this situation. We felt that this design also compared realistically the value of PMV to its most intuitive alternative: the lack of PMV provision, i.e., withdrawal of ventilation based on either patients’ or their families’ preferences.

Table 1.

Scenarios by patient group

| Prolonged mechanical ventilation base-case |

| Mechanical ventilation ≥21 days with tracheostomy placement for non-ear, nose, and throat diagnosis |

| Alternative strategy |

| Withdrawal of ventilation from a patient receiving mechanical ventilation for at least 7 days but less than 21 days |

| Other scenarios: |

| Prolonged mechanical ventilation (alternative definition) |

| Mechanical ventilation ≥4 days plus tracheostomy for non-ear, nose, and throat diagnosis |

| Short-term mechanical ventilation |

| Mechanical ventilation for ≥2 days but ≤7 days |

We followed recommendations for the conduct of cost-effectiveness analyses, incorporating a societal perspective (that of the perfect healthcare payor, i.e., a payor source that would reimburse costs uniformly and without exclusion for all relevant societal members), a lifetime time horizon, and a three percent annual discount rate. (17) All costs were adjusted to 2005 $ using the medical component of the consumer price index. (18)

Wherever possible we based the clinical and economic inputs included in our model on what we felt were the most relevant, highest quality published studies (Table 2). When we felt the literature was unclear, particularly with regard to the clinical characteristics and costs of those who had mechanical ventilation withdrawn, we informed our estimates with data from an observational cohort study of 817 persons who received mechanical ventilation for ≥48 hours at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and who subsequently had survival, functional status, and quality of life assessed at baseline as well as 3, 6, and 12 months from the time of intubation. (19) Because of the quality of its systematic screening process, the richness of data captured, and cohort size, the Pittsburgh dataset primarily was used to inform estimates of hospital survival, discharge disposition, as well as the characteristics and costs of those who had ventilation withdrawn for comfort measures as described elsewhere. (3)

Table 2.

Input Variables and Sources for Base-Case Scenario and Ranges for Sensitivity Analyses

| Variable | Base-Case Estimate | Range | Data Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | ||||||

| Discharge | ||||||

| Probability of discharge from hospital to: | (3, 46) | |||||

| Home | 10% | 10–25% | ||||

| LTAC | 25% | 15–30% | ||||

| SNF | 28% | 20–35% | ||||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 37% | 25–45% | ||||

| Probability of discharge from LTAC to: | ||||||

| Home | 10% | 5–18% | (9), Estimate | |||

| Hospital (readmission) | 30% | 25–35% | (47) | |||

| SNF | 45% | 50–70% | (9), Estimate | |||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 15% | 12–20% | (9), Estimate | |||

| Probability of discharge from SNF to: | ||||||

| Home | 5% | 0–10% | (3) | |||

| Hospital (readmission) | 23% | 10–43% | (3, 48–50) | |||

| Long- term nursing home | 45% | 30–58% | (9, 48) | |||

| Long-term nursing home, vent-dependent |

15% | 5–25% | (9) | |||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 12% | 5–20% | (3, 50) | |||

| Probability of discharge from inpatient rehabilitation to: | ||||||

| Home | 70% | 42–80% | (3) | |||

| Hospital (readmission) | 15% | 10–38% | (49, 51) | |||

| Nursing home | 15% | 9–20% | (3, 52) | |||

| Mortality | ||||||

| Hospital, initial† | 36% | 25–45% | (2, 3) | |||

| Home, year one | 30% | 25–50% | (3, 49) | |||

| Hospital readmission | 30% | 24%–36% | (31) | |||

| Hospital readmission with ICU, OR | 1.5 | 1–2 | (53) | |||

| LTAC | 25% | 18–58% | (9, 46, 47) | |||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 5% | 2–29% | (49, 54) | |||

| SNF | 21% | 5–40% | (47–49) | |||

| Readmission** | ||||||

| Probability of hospital readmission from home, annual‡ | ||||||

| 50% | 30–65% | (3, 31, 47, 49) | ||||

| Probability of ICU admission with hospital readmission | ||||||

| 10% | 5–25% | (3) | ||||

| Probability of hospital readmission from SNF, annual | ||||||

| 23% | 10–43% | (3, 48, 49) | ||||

| Probability of hospital readmission from LTA C, annual | ||||||

| 31% | 20–40% | (3, 47) | ||||

| Probability of hospital readmission from inpatient rehabilitation facility, annual | ||||||

| 15% | 10–38% | (3, 49, 51) | ||||

| Utilities | ||||||

| Hospital | 0.60 | 0.50–0.76 | (3, 55) | |||

| LTAC | 0.64 | 0.60–0.76 | (3)* | |||

| SNF | 0.63 | 0.60–0.76 | (3)* | |||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 0.66 | 0.60–0.76 | (3)* | |||

| Home, year one | 0.66 | 0.60–0.76 | (3)* | |||

| Home, years two and beyond | ||||||

| <45 | 0.85 | 0.70–0.90 | (3)* | |||

| 45–54 | 0.76 | 0.65–0.85 | (28) | |||

| 55–64 | 0.74 | 0.60–0.80 | (28) | |||

| 65–74 | 0.73 | 0.60–0.80 | (28) | |||

| 75–84 | 0.68 | 0.55–0.75 | (28) | |||

| >85 | 0.61 | 0.50–0.70 | (28) | |||

| Costs | ||||||

| Hospitalization∥ | ||||||

| PMV | $120,370 | $83,411–$152,709 | (3, 5) | |||

| Withdrawal | $52,269 | $21,575–$80,725 | (3, 5) | |||

| Hospital readmission, no ICU required | $13,627 | $7,237–$29,699 | (26, 30, 31) | |||

| Hospital readmission, ICU required | $23,725 | $14,515–$45,818 | (23, 26, 30) | |||

| Post-hospital care# | ||||||

| LTAC | $71,641 | $53,731–$89,551 | (3, 56) | |||

| Skilled nursing facility | $8,244 | $6,183–$10,305 | (3, 46) | |||

| Long-term nursing home, day | $166 | $116–230 | (57) | |||

| Long-term nursing home with ventilator care, day | $449 | $200–600 | (57) | |||

| Inpatient rehabilitation facility | $27,197 | $20,398–$33,996 | (46, 58) | |||

| Home health care | $2,851 | $2,138–$3,564 | (59) | |||

| Age-related health costs, year | (25) | |||||

| 18–39 | $1,796 | $1,347–$2,245 | ||||

| 40–64 | $3,226 | $2,420–$4,032 | ||||

| 65–84 | $12,706 | $9,530–$15,883 | ||||

| >85 | $21,172 | $15,879–$26,465 | ||||

| Other | ||||||

| Discount factor | 3% | 1–5% | (17) | |||

Derived from original Pittsburgh cohort using the methods of Brazier, et al. (60)

Value used for PMV patients defined by ventilation ≥4 days plus placement of tracheostomy (DRG 541/542) used in analyses was 23% (range 17–50%). (2, 3) Value for short-term ventilation (ventilation ≥2 days and <7 days) patients was 36% (range 31–44%). (3, 29)

Value for first post-discharge year. For the following three years, this rate was successively halved.

For short-term ventilation patients, values were home 15% (range 7–33%), from SNF 23% (range 10–43%), from LTAC 29% (range 25–35%), and from inpatient rehabilitation facility 12% (10–38%). (3, 47–49, 53)

Hospital costs for PMV patients defined by ventilation ≥4 days plus placement of tracheostomy (DRG 541/542) were $111,194 (range $83,411–$132,211). (3, 5) Hospital costs for short-term ventilation patients were $45,818 (range $21,575–$68,046). (3, 5)

For short-term ventilation patients, costs for LTAC care were $52,817 (range $49,120–$56,514) and skilled nursing facility were $4,319 (range $3,239–$5,398). (47)

ICU=intensive care unit, LTAC=long-term acute care facility, SNF=skilled nursing facility, MV=mechanical ventilation, PMV=prolonged mechanical ventilation (mechanical ventilation ≥21 days), OR=odds ratio.

We used TreeAge Pro 2006 (TreeAge Software, Inc.; Williamstown, MA) and Stata 9 (Stata; College Station, TX) in our analyses. The Duke University Institutional Review board exempted our research from formal review.

Patient population

Base-case patient

The base-case patient was a 65-year old, critically ill recipient of PMV who was a composite of genders and ethnicities. This reflects the average PMV patient age reported in other studies and assures Medicare eligibility. (2) All base-case PMV patients were assumed to have been ventilated for ≥21 days and to have had a tracheostomy placed. Although 22% of those ventilated for ≥21 days in the Pittsburgh dataset did not undergo tracheostomy placement, they did not have either statistically different mortality or costs than those with tracheostomies. We did not distinguish between medical and surgical patients, as others have found previously that there was no significant difference in adjusted one-year survival in this age group based on these groupings. (19)

Comparison patient

The comparison group included those patients from whom ventilation was withdrawn without placement of a tracheostomy between ventilator days 7 and 21. Because the effect of ventilator withdrawal was assumed to be early death, severity of illness and other clinical factors, although part of the decision-making process, were less relevant to the model than the decision to withdraw ventilation itself in anticipation of death based on patients’ or their families’ wishes. For the patients in the withdrawal of ventilation group based on the Pittsburgh cohort, the median duration of care included 12 ventilator days (interquartile range 10, 15), 13 ICU days (11, 16), and 16 hospital days (12, 19). Their median ICU day one APS was 60 (42, 78) and they had an average of three limitations in basic instrumental activities of daily living. There was variation in length of stay among patients in the Pittsburgh dataset from whom ventilation was withdrawn. However, this variation served primarily to inform adjustments in reimbursement based on hospital length of stay outliers status since overall group costs were based on Medicare’s diagnosis related group code 475 (acute respiratory failure) as described below.

Process of care characteristics and clinical input values

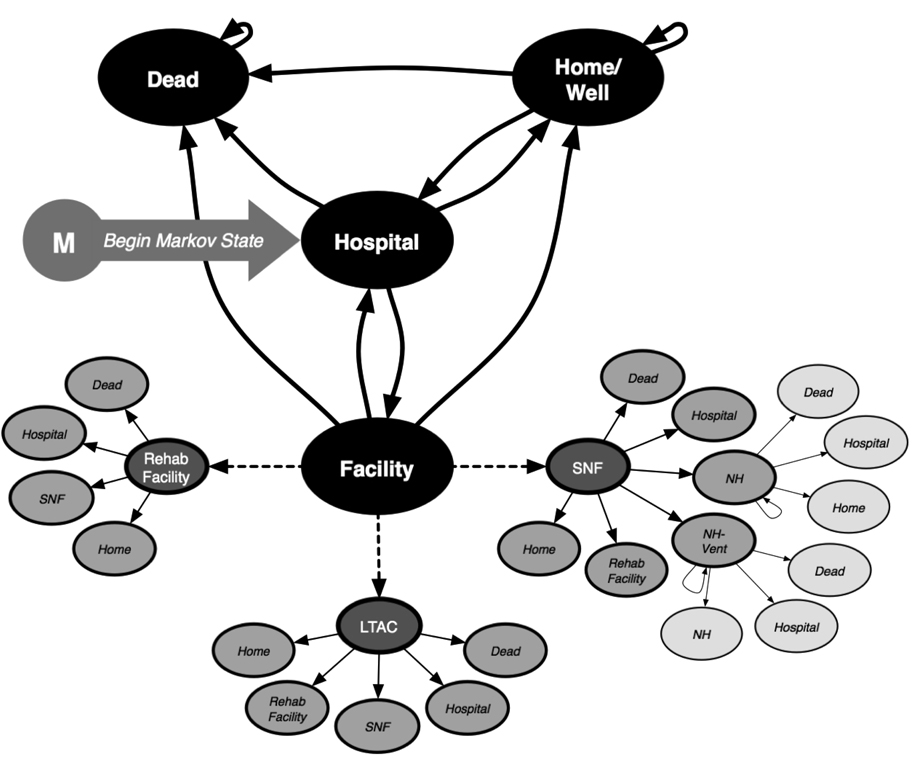

We attempted to examine in our analyses a realistic trajectory of acute, post-acute, and chronic facility-based care that a PMV recipient might experience. In our model, a hospital survivor could be discharged either to home or a post-acute care facility (long-term acute care [LTAC], skilled nursing [SNF], inpatient rehabilitation, or nursing home facility) (Figure 1 and Figure 2; also Table 2). If residing at home, a patient either remained healthy, experienced complications resulting in hospital readmission, or died. Persons discharged to post-acute care facilities could be discharged home subsequently, experience complications resulting in hospital readmission, or be transferred to another post-acute care facility. Additionally, skilled nursing facility discharges could be transitioned to a long-term nursing home or a nursing home with expertise in long-term ventilator management for those unable to be weaned completely from ventilation.

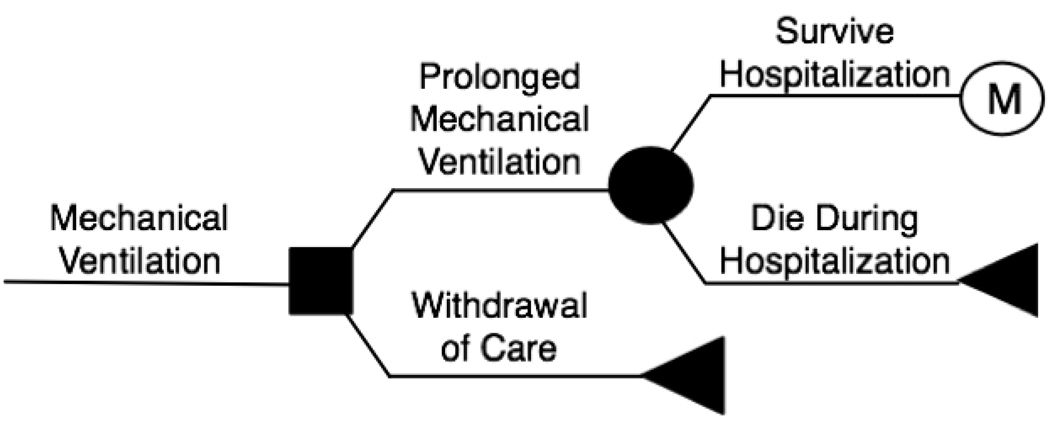

Figure 1. The Decision Model.

The solid box on the left represents the decision made between provision of prolonged mechanical ventilation or withdrawal of care. The circle represents a chance node. Triangles represent death. The encircled “M” represents entry into the Markov tree (see also Figure 2). MV = mechanical ventilation.

Figure 2. Markov Model.

The Markov model represents clinical states in which a person could exist during each one-week period as they are followed until death: a person can live at home, be cared for at a post-acute care facility, be readmitted to an acute care hospital for complications, or die. The dashed lines extending from the post-acute care facility state depict in greater detail what patients may experience should they be discharged to one of these care locations. LTAC=long-term acute care facility, SNF=skilled nursing facility, NH=long-term nursing home.

Clinical effects

Incremental cost-effectiveness of PMV was determined by using a Markov model in which outcomes during continuous cycles of one week were calculated until no survivors remained. (20) We expressed our results in terms of costs, life-years, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). ICERs represent the ratio of incremental costs (costs of strategy 1 - costs of strategy 2) to incremental effects (life-years of strategy 1 - life-years of strategy 2). Because we adjusted life-years for quality of life as quantified in the form of utilities, ICERs are reported as costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Utilities are global quality of life measures particularly appropriate for analyses that take a societal perspective and can range from 0 (death) to 1 (ideal health).

We used the declining exponential approximation of life expectancy (DEALE) method to build survival curves based on life expectancy predicted from US life tables. (21, 22) The DEALE method generates a constant mortality rate over time predicted by the equation s=e-rt (s=lifetime survival, r=constant mortality rate, t=time in years). We estimated that the base-case patient’s life expectancy would be reduced by an amount (25%) similar to the observed one-year mortality observed for PMV patients discharged directly home in the Pittsburgh cohort. (3) Therefore, the average PMV patient would have a life expectancy of 13.7 years—25% less that the 18.2 years expected of a typical 65-year old composite of gender, ethnicity, and race. (22) Such life expectancy corrections have been used in past cost-effectiveness analyses addressing the critically ill and are borne out by observational studies of survivors of sepsis and mechanical ventilation. (23, 24)

Costs

We incorporated in the model only direct costs attributable to patient care, excluding indirect costs such as hospital overhead costs, days lost from work, and others (Table 2). No additional costs were included for death occurring during hospitalization. Although we incorporated age-specific annual future expected health costs based on both Medicare and Blue Cross & Blue Shield datasets, we did not assume extra outpatient visits were required in the months following hospital discharge. (25)

Because base-case patients were assumed to be 65 years of age, acute and post-acute care costs were based on diagnosis-specific weightings and adjusted by length of stay data derived from the Pittsburgh cohort. (3, 26, 27) Briefly, Medicare’s inpatient prospective payment system provides reimbursement by multiplying a standardized base payment by one of 526 condition-specific relative weights called diagnosis related groups (DRGs). This amount is then adjusted by a local wage index, a credit for medical education, and a hospital’s volume of care provision to poor patients. (27) For patients with especially short or long stays, there are additional algorithms for calculating additional “outlier” payments. Similar reimbursement procedures are followed for most facility-based post-acute care. Our cost calculations are described in detail in the Technical Appendix.

Sensitivity and Stratified Analyses

We performed one-way and multi-way probabilistic (Monte Carlo) sensitivity analyses to explore the effect that our estimates’ uncertainty had on costs and effectiveness. Ranges for clinical variables included in the sensitivity analyses were based on the most representative data available (Table 2). In one-way sensitivity analyses, individual data inputs were varied across defined ranges to understand the importance of each to the overall model. Monte Carlo analyses allowed us to vary simultaneously all input data values in the model based on specific distributions over 1,000 simulations. (20) We assigned uniform distributions for costs and utilities and used beta distributions (shape defined by number of persons at risk for an event and the number not at risk; minimal value=0 and maximal value=1) for probabilities. The results of Monte Carlo analyses were quantified by the proportion of the simulations that were showed ICERs <$100,000 per QALY.

We also performed stratified analyses to explore areas of particular clinical interest including age, probability of one-year survival, and post-acute care discharge disposition.

(a) Age

We performed separate analyses by age (18, 45, 55, 65, 70, 75, 80, and 85) for the base-case PMV patient who received mechanical ventilation for ≥21 days. For these analyses, we used the Pittsburgh cohort, published data, and US life tables to adjust by age group input variables including hospital mortality, costs, discharge disposition location (home, LTAC, skilled nursing facility, or inpatient rehabilitation facility), and readmission rates. (3, 22, 28)

(b) Probability of death at one year

We built a logistic regression model using the Pittsburgh dataset to stratify patients’ risk of one-year death as high (≥50% probability) or low (<50%) based on specific clinical variables. The final model included age and pre-admission number of limitations in instrumental activities of daily living, while day one acute physiology score, gender, ethnicity, admission source, admitting service, admission diagnostic category, and pre-admission activities of daily living limitations did not contribute significantly to the model. This model is similar to that described previously. (19) Costs and survival of the base-case PMV patients in the original cohort were then calculated as described above and added to the model.

(c) Discharge disposition

We examined the effect that routine early hospital discharge to an LTAC had on cost-effectiveness ratios by modeling both a 14 day and 21 day hospital stay for cohorts of 1,000 PMV patients who all were sent to LTACs if they survived the hospitalization. We assumed that the summative duration of hospital plus LTAC care did not change overall. We reduced hospital mortality rates to 20% and increased LTAC mortality rates to 35% to account for the expected shift in mortality from one care location to the other. We also increased the probability of readmission from LTAC to hospital to 36% and 40% for 21- and 14-day hospital stays, respectively.

Finally, for purposes of contextual framing, we also performed analyses comparing ventilation withdrawal and both (a) a patient characterized by an alternative PMV definition used by Medicare (DRG 541 and 542 [receipt of mechanical ventilation for at least 4 days with tracheostomy placement for reasons other than a head, neck, or throat diagnosis with or without an operative procedure], previously known as DRG 483) as well as (b) a patient ventilated short-term for an average length of time based on epidemiological studies (ventilated ≥2 days but ≤7 days) (Table 1). (29)

RESULTS

Providing mechanical ventilation for 21 or more days to the 65-year-old base-case patient gained 2.593 life-years or 1.745 QALYs at a cost of $143,808 compared to ventilation withdrawal. Therefore, the incremental costs of PMV were $55,460 per life-year and $82,411 per QALY gained (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios

| Scenario | Costs | Effectiveness | Change in Cost |

Change in Effectiveness |

Incremental CE Ratios |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LE | QALE | LE | QALE | $/LY | $/QALY | |||

| Base-case | ||||||||

| MV ≥21d | $196,077 | 2.651 | 1.774 | $143,808 | 2.593 | 1.745 | $55,460 | $82,411 |

| Withdrawal* | $52,269 | 0.058 | 0.029 | |||||

| Alternate scenarios | ||||||||

| MV ≥4 days + trach | $207,184 | 3.186 | 2.133 | $154,915 | 3.128 | 2.104 | $49,525 | $73,629 |

| Withdrawal* | $52,269 | 0.058 | 0.029 | |||||

| Short-term MV | $114,397 | 4.922 | 3.284 | $92,822 | 4.864 | 3.255 | $19,083 | $28,517 |

| Withdrawal† | $21,575 | 0.058 | 0.029 | |||||

Short-term MV=≥2d & ≤7d of mechanical ventilation, LE=life expectancy, QALE=quality-adjusted life expectancy, QALY=quality-adjusted life-year, CE=cost-effectiveness, MV=mechanical ventilation, trach=tracheostomy.

Based on Pittsburgh cohort patients from whom ventilation was withdrawn between ventilation days 7 and 21* and by day 4†.

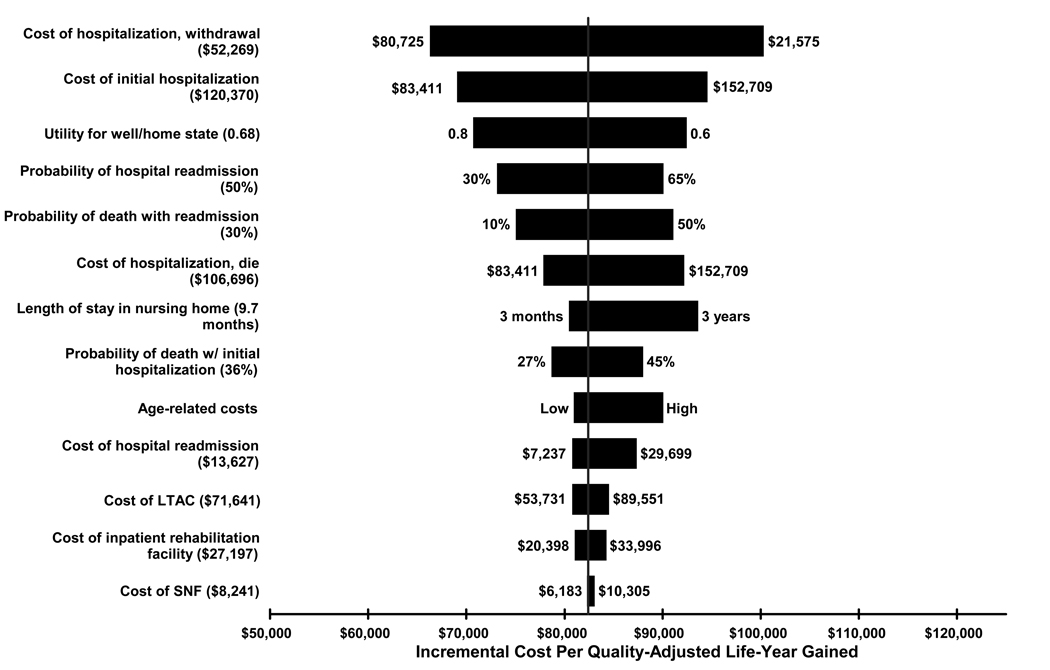

One-way sensitivity analyses showed that incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were most sensitive to variance in acute hospitalization costs and readmission rate, aside from changes in costs of the comparison group (Figure 3). PMV was associated with costs of nearly $100,000 per QALY when hospitalization costs were maximized to $152,709 (base-case value $120,370) and slightly more than $70,000 per QALY using the lower cost estimate of $83,411. Increasing the probability of first-year readmission to 65% (base-case 50%) increased the cost per QALY to $90,000 while reducing the rate to 30% resulted in costs per QALY of $73,000. Varying age-related lifetime expected health costs had a more moderate affect on cost-effectiveness ratios. Interestingly, variation in post-acute care facility-based mortality and costs had a relatively minor effect on cost-effectiveness ratios. Considering the uncertainty across all data inputs in the model simultaneously, Monte Carlo probabilistic analyses demonstrated that there was a 75% probability that the incremental costs per QALY gained by providing PMV care to the base-case patient compared to ventilation withdrawal were <$100,000.

Figure 3. Tornado Diagram.

The tornado diagram represents the results of one-way sensitivity analyses. It shows how varying the range of each input variable (base-case values in parentheses) separately in the decision model affects incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (cost per QALYs) when provision of mechanical ventilation for 21 or more days is compared to ventilation withdrawal. The vertical red line represents the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of the base-case analysis, $82,411 per QALY gained. LTAC=long-term acute care facility and SNF=skilled nursing facility.

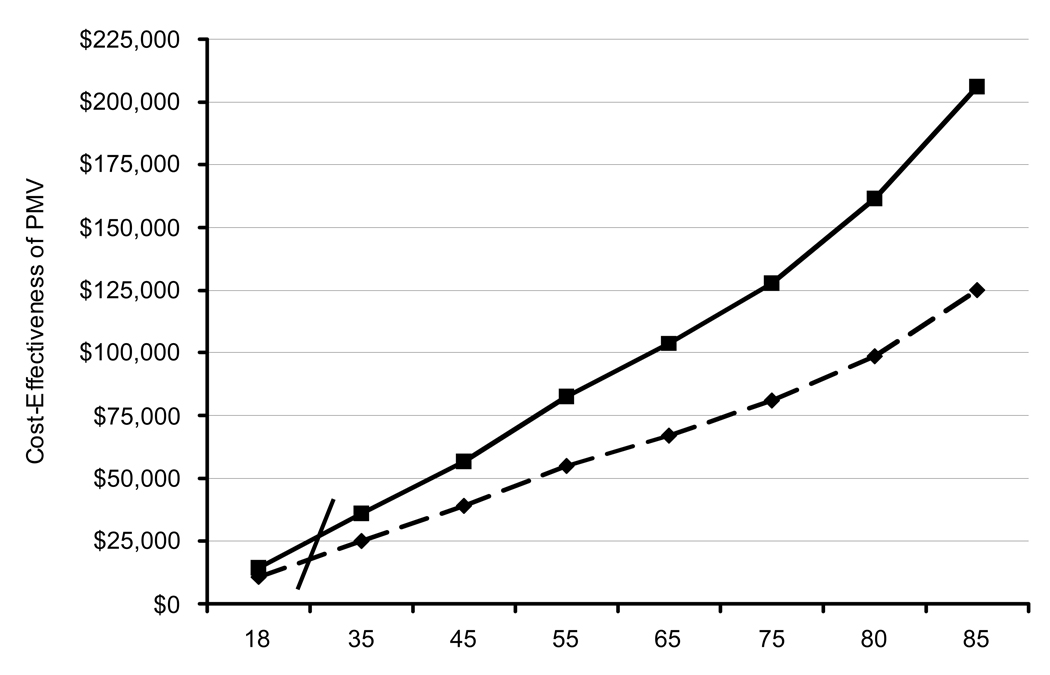

The effect of patient age on incremental cost-effectiveness ratios was the most profound of any input variable tested, as shown in Figure 4. PMV provision to 18 year-olds was associated with incremental costs of $14,289 per QALY gained compared to $127,859 for a 75 year-old and over $206,000 for an 85 year-old. Incremental costs per QALY gained with PMV provision exceeded $100,000 at age 68.

Figure 4. Affect of Age on Cost-Effectiveness Ratios.

This graph demonstrates both incremental costs per life-year (dashed line) and incremental costs per QALY (solid line) of PMV provision compared to withdrawal of ventilation, stratified by patient age.

We found that there were wide differences in costs per QALY based on probability of one-year mortality. Table 4 shows that compared to ventilation withdrawal, it cost $60,967 per QALY gained to provide PMV to the base-case 65 year-old with a <50% probability of one-year mortality while it cost $101,787 to do the same for a more severely ill patient with a ≥50% likelihood of death by one year. This difference was primarily related to improved survival rather than reduced costs in the group with a better prognosis.

Table 4.

Cost-effectiveness by probability of death at one year*

| Scenario | Costs | Effectiveness | Change in Cost |

Change in Effectiveness |

Incremental CE Ratios |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LE | QALE | LE | QALE | $/LY | $/QALY | |||

| PMV | ||||||||

| prob. of death <50% | $221,233 | 4.071 | 2.732 | $164,793 | 4.013 | 2.703 | $41,065 | $60,967 |

| Withdrawal† | $52,269 | 0.058 | 0.029 | |||||

| PMV | ||||||||

| prob. of death ≥50% | $191,817 | 1.989 | 1.330 | $135,377 | 1.876 | 1.301 | $72,163 | $101,787 |

| Withdrawal† | $52,269 | 0.058 | 0.029 | |||||

Probability of death at one year for persons aged 65 who are ventilated for ≥21 days. Based on odds ratios generated from a logistic regression model that included age and number of limitations in instrumental activities of daily living.

Based on Pittsburgh cohort patients from whom ventilation is withdrawn between ventilation days 7 and 21.

LE=life expectancy, QALE=quality-adjusted life expectancy, QALY=quality-adjusted life-year, CE=cost-effectiveness, PMV=prolonged mechanical ventilation (mechanical ventilation ≥21 days).

Considering only persons discharged to LTACs, routine early transfer to an LTAC on ICU day 14 was associated with a reduction in average costs per QALY of more than $46,000 ($94,558 per QALY vs. $141,608 per QALY) without adjustment for possible increases in LTAC mortality and hospital readmission rates. However, given a lower hospital mortality (20%) and a higher probability of LTAC death (30%), hospital readmissions from LTACs would need to be kept below 50% for cost savings to be realized with the early transfer strategy compared to the base-case LTAC strategy.

Finally, when we defined PMV using Medicare terminology (mechanical ventilation ≥4 days plus tracheostomy placement; DRG 483), the incremental costs of $73,629 per QALY were found to be very similar to those of the base-case patient. PMV costs by either definition were significantly greater than the $28,517 per QALY gained by care of a patient who required at least 2 but <7 days of ventilation.

DISCUSSION

We found that providing PMV is expensive for the base-case 65-year old patient, though within the upper limits of conventional acceptability based on costs of $82,411 per QALY compared to withdrawal of ventilation in anticipation of death. However, the societal value of PMV provision becomes significantly less as patient age approaches the late 60s and the likelihood of short-term death increases beyond 50%. Although post-acute care resource utilization is an increasing concern for the critically ill, the incremental cost-effectiveness of PMV provision was much less sensitive to these costs than factors including patient age, costs of acute hospital care, and readmission rates.

Implications

Our findings are noteworthy because the elderly, who presently account for over half of all ICU days and who had the highest lifetime incremental costs per QALY, are disproportionately affected by PMV. (2) Further, the number of elderly persons will grow significantly in the coming decades, potentially outpacing the supply of critical care physicians and drastically expanding Medicare costs. (12, 30) Therefore, our finding that the provision of an intervention that is steadily increasing in incidence yet associated with both exceedingly high costs and poor outcomes among the expanding numbers of the very old highlights the potential future burden of chronic critical illness for which societal members should now plan. Maximizing the societal value of PMV will require both the development of interventions designed to improve PMV patients’ health outcomes and reduce resource utilization as well as thoughtful consideration of the appropriateness of prolonged ventilation provision in high risk patients.

Our analyses are helpful in generating hypotheses about and directing the timing of PMV process of care changes. We found that an intervention that produced as minimal as a 10% improvement in utility reflecting quality of life has a noticeable affect on cost-effectiveness ratios. Potentially valuable resources for PMV survivors might include ICU follow up clinics, rehabilitation programs, and disease management programs. (5, 31, 32) However, because of high early mortality and resource utilization, the potential impact of any PMV-specific interventions appears to be greatest when focused on acute care venues. Wider development of respiratory care units with lower nurse-to-patient ratios than found in intensive care units is one example of how acute hospitalization costs can be decreased, especially for hospitals without access to LTACs. (33) Earlier transfer of PMV patients from intensive care units to lower cost post-acute care facilities such as LTACs may not reduce overall costs. Such a policy may only shift the burden of unstable acute and chronic critical illness to another care location ill-equipped to handle it, resulting in either higher LTAC mortality or more readmissions to acute hospitals. (10) However, we were unable to determine the potential societal benefit associated with the gain of open ICU beds that might be achieved with early LTAC transfer—an issue of growing relevance to the healthcare system given the expansion of critically ill patients expected in the coming decade. Although there is a multiplicity of post-acute care venues that participate in PMV care such as LTACs, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation facilities, and others, it is unknown if care in any one type is associated with better outcomes. At present, long-term care hospitals appear to vary widely in their staffing patterns, admission criteria, and outcomes. (34) The impact of post-acute care facility type on PMV care deserves further attention.

The wide difference in cost-effectiveness ratios we found based on age and predicted mortality emphasizes the potential importance of prognostic models for survival, quality of life, and functional status for this population. Access to prognostic data does not change clinicians’ practice in certain situations, but more confident knowledge of prognosis may improve the quality of patient-clinician and family-clinician communication in the ICU setting. (35, 36) Skilled communication about quality of life, survival, and caregiving needs also may prepare families for expected needs, ensure a patient's wishes are followed appropriately, can result in reduction in time spent in the ICU prior to death, and has been associated with increased family satisfaction. (37–39)

Comparison with other literature

This is the first extensive economic analysis of PMV to our knowledge, though our findings both complement and extend previous economic research pertaining to the critically ill. Cohen and colleagues reported that the cost per year of life saved by providing mechanical ventilation to persons aged 80 and older was approximately $160,000 (2005 $), similar to our $153,461 figure for 80 year-old PMV patients. (40) Hamel and colleagues found that severely ill persons aged 65–74 who had a >50% risk of death at two months had lifetime incremental costs exceeding $132,000 per QALY (2005 $) gained by providing ventilation compared with withholding ventilation—somewhat higher than the $101,787 per QALY it cost high-risk PMV patients in our analysis. (41) In contrast to these authors, we observed lower age-based survival and higher costs per QALY with advancing age. However, Heyland found that treating general ICU patients for more than 14 days cost only $5,300 (2005 $) per life-year saved compared to withdrawal of care, though this assumed a 15-year survival and a comparatively low severity of illness. (16)

The cost-effectiveness ratios associated with PMV provision are much higher than other medical therapies accepted as cost-effective among the critically ill such as the $27,400 per QALY gained by provision of drotrecogin alpha to persons with severe sepsis or the cost-savings of antiseptic-impregnated central venous catheters. (23, 42) PMV’s value is significantly less than many therapies for the non-critically ill elderly including the use of statins after myocardial infarction ($18,100 per QALY) or influenza vaccination (cost-saving). (43, 44) Some may feel that a standard cost-effectiveness benchmark of $50,000 per QALY is inappropriately low for the critically ill population, but many societal members nonetheless may view as excessive the outlay of $162,000 per QALY for PMV provision to high risk 80-year-olds. (13)

Limitations

Our analyses have important limitations. First, we used a number of different sources of data, which could introduce systemic bias. However, we used what we felt to be the best estimates available from the medical literature, explored the range of data inputs in sensitivity analyses, and still found our results to be relatively robust. Also, because the withdrawal of ventilation comparator was based on results of an observational study and not a randomized trial comparing ventilation strategies, the clinical characteristics of base-case and comparison patients are not perfectly matched. We believe, however, that this was the most clinically realistic way to estimate what patient costs and benefits would be if a course of PMV was not pursued. We did not include physician costs because of difficulty standardizing acute and post-acute care payments for these services. Given the similar inpatient costs and low post-discharge survival, the importance of this deficit is unlikely to change our primary findings that PMV incremental cost effectiveness ratios are generally high. Also, because of the limitations of our data sources, we were unable to determine how specific disease states and detailed aspects of resource utilization affected costs and effects. Finally, we do not intend to dehumanize the clinician-patient and clinician-family dynamic with our analyses, especially considering the importance physicians place on interpreting patients’ wishes in the setting of withdrawing life-sustaining therapies. (45) Nonetheless, we believe that a pragmatic societal perspective is most appropriate for economic analyses that have implications for maximizing resource distribution.

CONCLUSIONS

Our analyses show that PMV provision is associated with low cost-effectiveness among the elderly and those with a low likelihood of one-year survival. Ideally, the development of PMV-specific prognostic models could facilitate communication of likely health outcomes and help maximize PMV value. Additional benefit could be realized by reducing costs of acute hospitalization with lower intensity units for stable patients and by minimizing post-acute care complications, thereby reducing readmissions and increasing quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Support: National Institutes of Health grants K23 HL081048 (C.E.C.), K23, HL067068 (S.S.C.), and R01 AG11979 (L.C.)

Technical Appendix: Cost Calculations

Inpatient Costs

Inpatient hospitalization for PMV and short-term ventilation patients

There is no specific DRG code for persons ventilated for ≥21 days, though most of these patients qualify for DRG 483 (now DRG 541 or DRG 542 as previously described) on the basis of tracheostomy placement for reasons not related to a head and neck diagnosis. (3) Therefore, we estimated base-case costs by first calculating total hospital costs for PMV patients in the Pittsburgh database by hospital-specific Medicare cost-charge ratios. Next, we calculated total payor costs by adding high-cost outlier payments to the standard DRG reimbursement based on a 45 day stay and adjustment for geographic area, disproportionate share factors, and medical education provision. Lower and upper ranges in sensitivity analyses were based on DRG 541/542 costs without outlier correction ($111,194) and the 95thpercentile of length of stay (70 days) and associated costs of $185,770. Costs for patients defined by the alternate PMV definition (ventilation ≥4 days with tracheostomy placement) were based also on DRG 541/542 without outlier correction ($111,194). For short term mechanical ventilation patients (≥2 days but < 7days), costs ($45,818) were based on standard payments for DRG 475 (acute respiratory failure without tracheostomy placement) adjusted for outlier status derived from the cohort.

Inpatient hospitalization for withdrawal of ventilation patients

For patients from whom ventilation was withdrawn between ventilator days 7 and 21, the comparator group to both PMV groups, the payor’s costs of $52,269 were calculated from the Pittsburgh cohort data as described above based on DRG 475 with adjustment for length of stay outlier status. (7) The withdrawal of ventilation comparison group for the short-term ventilation group was assumed to receive the standard DRG 475 reimbursement of $21,575.

Hospital readmission costs

Because most recent critical care recipients’ readmissions are directly related to the original disease process, we assumed that readmission would cost $13,627 based on a diagnosis a PMV recipient might commonly experience—pneumonia (DRG 79). (26, 31, 53) In sensitivity analyses, we chose a lower bound corresponding to the average floor admission paid by Medicare ($7,237) and an upper bound based on average costs ($26,699) derived from a recent study of prolonged ventilation patient readmissions. (30, 31) Patients who required intensive care were assumed to have a pneumonia that progressed to sepsis (DRG 416) and to have total hospital costs of $23,725. (26) Cost ranges in sensitivity analyses included an upper bound corresponding to that seen for respiratory failure necessitating ventilation used for the comparator short-term ventilation group (DRG 475; $45,818) and a lower bound representing the average Medicare payment for ICU care ($14,515 after adjustment to 2005 $). (30)

Post-acute Care Costs

We calculated long-term acute care facility (LTAC) costs ($71,641) by adjusting the 2005 standard federal prospective payment rate for LTACs by the Pittsburgh area wage index, the long-term care hospital relative weight for DRG 475, and the budget neutrality offset factor. (56) Skilled nursing facility (SNF) costs on based average Medicare payments for patients coded as DRG 483 during their acute hospitalization and adjusted for the case-mix, functional status, and comorbidities. (46) The cost for an episode of long-term nursing home care ($45,152) was calculated by multiplying the average length of stay for long-term nursing home residents 65 and older (272 days) by the average per diem cost ($166). (48, 50, 57) For those managed in a nursing facility with expertise in chronic ventilation care, we also assumed an average length of stay of 272 days but included per diem costs of $449 based on Medicaid data. (57) Medicare inpatient rehabilitation payments for patients ($27,197) were based on standard reimbursements weighted for case-mix and geographic location. (58) Home health care payments ($2,851) were estimated for all persons discharged home from an acute care facility by adjusted the average base payment made for the first 60 days of care by Medicare for case-mix. (59) Finally, we incorporated age-specific annual future expected health costs based on both Medicare and Blue Cross & Blue Shield datasets. (25)

REFERENCES

- 1.Kersten A, Millbrandt MB, Rahim MT, et al. How big is critical care in the US? Crit Care Med. 2004:A8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson SS, Bach PB. The epidemiology and costs of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox CE, Carson SS, Hoff-Linquist JA, et al. Differences in one-year health outcomes and resource utilization by definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R9. doi: 10.1186/cc5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seneff MG, Zimmerman JE, Knaus WA, et al. Predicting the duration of mechanical ventilation: the importance of disease and patient characteristics. Chest. 1996;110:469–479. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacIntyre NR, Epstein SK, Carson S, et al. Management of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: report of a NAMDRC consensus conference. Chest. 2005;128:3937–3954. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox CE, Carson SS, Holmes GM, et al. Increase in tracheostomy for prolonged mechanical ventilation in North Carolina, 1993–2002. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2219–2226. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000145232.46143.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare provider analysis and review: long-term care hospitals. [cited August 8, 2005]; Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov.

- 8.Nelson JE, Meier DE, Litke A, et al. The symptom burden of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1527–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000129485.08835.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carson SS, Bach PB, Brzozowski L, Leff A. Outcomes after long-term acute care. An analysis of 133 mechanically ventilated patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1568–1573. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9809002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheinhorn DJ, Chao DC, Stearn-Hassenpflug M, et al. Post-ICU mechanical ventilation: treatment of 1,123 patients at a regional weaning center. Chest. 1997;111:1654–1659. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, et al. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284:2762–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.21.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann PJ, Rosen AB, Weinstein MC. Medicare and cost-effectiveness analysis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1516–1522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb050564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorman T, Pauldine R. Economic stress and misaligned incentives in critical care medicine in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:S36–S43. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000252911.62777.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talmor D, Shapiro N, Greenberg D, et al. When is critical care medicine cost-effective? A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness literature. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2738–2747. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000241159.18620.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyland DK, Konopad E, Noseworthy TW, et al. Is it 'worthwhile' to continue treating patients with a prolonged stay (>14 days) in the ICU? An economic evaluation. Chest. 1998;114:192–198. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, et al. Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:1253–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [cited July 27, 2006];Consumer price indexes. Available from: www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm.

- 19.Chelluri L, Im KA, Belle SH, et al. Long-term mortality and quality of life after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:61–69. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098029.65347.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Critchfield GC, Willard KE. Probabilistic analysis of decision trees using Monte Carlo simulation. Med Decis Making. 1986;6:85–92. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8600600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck JR, Pauker SG, Gottlieb JE, et al. A convenient approximation of life expectancy (the "DEALE"). II. Use in medical decision-making. Am J Med. 1982;73:889–897. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Life Tables, 2002. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in the treatment of severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quartin AA, Schein RM, Kett DH, Peduzzi PN. Magnitude and duration of the effect of sepsis on survival. JAMA. 1997;277:1058–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alemayehu B, Warner KE. The lifetime distribution of health care costs. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital inpatient prospective payment systems and 2006 FY rates. Federal Register. 2005:47278–47707. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Assessing payment adequacy and updating payments for hospital inpatient and outpatient services. Washington, DC: [cited January 8, 2006]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/publications. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fryback DG, Dasbach EJ, Klein R, et al. The Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study: initial catalog of health-state quality factors. Med Decis Making. 1993;13:89–102. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA. 2002;287:345–355. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper LM, Linde-Zwirble WT. Medicare intensive care unit use: analysis of incidence, cost, and payment. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2247–2253. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000146301.47334.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Kelley CG, et al. Trial of a disease management program to reduce hospital readmissions of the chronically critically ill. Chest. 2005;128:507–517. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. Rehabilitation after critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2456–2461. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000089938.56725.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Douglas S, Daly B, Rudy E, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a special care unit to care for the chronically critically ill. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1995;25:47–53. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carson SS. Know your long-term care hospital. Chest. 2007;131:2–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12:317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynn J, Harrell F, Jr, Cohn F, et al. Prognoses of seriously ill hospitalized patients on the days before death: implications for patient care and public policy. New Horiz. 1997;5:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1679–1685. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218409.58256.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen IL, Lambrinos J, Fein IA. Mechanical ventilation for the elderly patient in intensive care. Incremental changes and benefits. JAMA. 1993;269:1025–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamel MB, Phillips RS, Davis RB, et al. Outcomes and cost-effectiveness of ventilator support and aggressive care for patients with acute respiratory failure due to pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Med. 2000;109:614–620. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veenstra DL, Saint S, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of antiseptic-impregnated central venous catheters for the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infection. JAMA. 1999;282:554–560. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ganz DA, Kuntz KM, Benner JS, Avorn J. Correction: cost-effectiveness of statins in older patients with myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:635. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nichol KL, Margolis KL, Wuorenma J, Von Sternberg T. The efficacy and cost effectiveness of vaccination against influenza among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:778–784. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409223311206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, et al. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1123–1132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Report to Congress: New approaches in Medicare. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2004. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Defining long-term care hospitals; pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Variation and innovation in Medicare. Washington, DC: 2003. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Monitoring post-acute care; pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 48. [cited January 10, 2006];Medicare payment policy: skilled nursing facility services. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/publications.

- 49.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Brennan PF, et al. Hospital readmission among long-term ventilator patients. Chest. 2001;120:1278–1286. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. [cited August 15, 2006];Gabrel CS. Characteristics of elderly nursing home current residents and discharges, results from the 1997 National Nursing Home Survey. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov. [PubMed]

- 51.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Report to Congress: utilization and beneficiary access to services post-implementation of the inpatient rehabilitation facility prospective payment system. 2005 August 15;:1–161. [cited March 30, 2006] Available from: http://www.cms.hhs.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan L, Ciol M. Medicare's payment system: its effect on discharges to skilled nursing facilities from rehabilitation hospitals. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:715–719. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenberg AL, Watts C. Patients readmitted to ICUs: a systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. Chest. 2000;118:492–502. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buntin MB, Carter GM, Hayden O, et al. Inpatient rehabilitation facility use before and after implementation of the IRF prospective payment system. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Institute; 2006. pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Angus DC, Musthafa AA, Clermont G, et al. Quality-adjusted survival in the first year after the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1389–1394. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2005123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Federal Register. Vol. 70. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Resources; 2005. Medicare program; prospective payment system for long-term care hospitals: annual payment rate update, policy changes, and clarification; final rule; pp. 24168–24261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grabowski DC, Feng Z, Intrator O, Mor V. Recent trends in state nursing home payment policies. Health Aff. 2004:W4-363–373. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Federal Register. Vol. 69. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Resources; 2004. Medicare program; inpatient rehabilitation prospective payment system for fiscal year 2005; pp. 45721–45775. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. [cited January 5, 2006];Post-acute care: skilled nursing facilities, home health services. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/publications.

- 60.Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42:851–859. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135827.18610.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]