Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of subsensory vibratory noise applied to the soles of the feet on gait variability in a population of elderly recurrent fallers compared to non-fallers and young controls. Eighteen elderly recurrent fallers and 18 elderly non-fallers were recruited from the MOBILIZE Boston Study (MBS), a population-based cohort study investigating novel risk factors for falls. Twelve young participants were included as controls. Participants performed three 6-minute walking trials while wearing a pair of insoles containing vibrating actuators. During each trial, the noise stimulus was applied for 3 of the 6 minutes, and differences in stride-, stance-, and swing-time variability were analyzed between noise and no-noise conditions. The use of vibrating insoles significantly reduced stride-, stance-, and swing-time variability measures for elderly recurrent fallers. Elderly non-fallers also demonstrated significant reductions in stride and stance time variability. Although young participants showed decreases in all variability measures, the results did not achieve statistical significance. Gait variability reductions with noise were similar between the elderly recurrent fallers and elderly non-fallers. This study supports the hypothesis that subsensory vibratory noise applied to the soles of the feet can reduce gait variability in elderly participants. Future studies are needed to determine if this intervention reduces falls risk.

Keywords: Stochastic resonance, gait, noise, variability, falls

INTRODUCTION

Falls are leading causes of traumatic death and trauma-related admissions to hospitals for elderly people [1]. They account for more than 90% of all hip fractures and are the primary cause of accidental deaths in individuals over age 65. In addition, falls limit mobility and daily task independence, causing an overall reduction in quality of life [2,3].

Falls are related to abnormalities in gait and balance, which can be attributed, in part, to age-related impairments in the sensory system. In our previous work, the application of subsensory vibratory noise to the soles of the feet during quiet standing effectively reduced postural sway via a phenomenon called stochastic resonance (SR) [3–5]. Although noise is typically viewed to be detrimental to systems, research has validated SR’s role in increasing the detection and transmission of weak signals [2,6,7]. In the somatosensory system, faint sensory input signals of low amplitudes do not cross sensory thresholds and cannot be transmitted. By combining the same faint input signal with a noise signal, an increase in the maxima of the original input occurs, crossing the sensory threshold. After exceeding the threshold, the sensory signal can serve to generate the appropriate motor function output. Vibrating insoles that apply a subsensory noise signal to the soles of the feet have reduced postural sway in people with diabetic neuropathy, stroke, and advanced age [3–5].

Since most falls occur during locomotion [8], it is important to investigate whether SR can be used to improve gait function in elderly people who experience falls. The mechanism through which vibration at the soles of the feet reduces postural sway is thought to involve improvements in somatosensory feedback and motor output to muscles associated with quiet standing. Thus, similar noise-induced increases in somatosensation may also benefit the dynamic task of walking by improving sensory feedback and motor control. Gait timing variability, a quantifiable measure of gait function, has been shown to predict falls [9–11].

Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effect of subsensory noise applied to the soles of the feet on gait variability in young adults, elderly non-fallers, and elderly recurrent-fallers. We hypothesized that noise-enhanced sensory input at the soles of the feet would reduce gait variability.

METHODS

Subject Recruitment

Elderly subjects were recruited from the MOBILIZE Boston Study (MBS), a population-based cohort study investigating novel risk factors for falls [12]. All 765 participants in the MBS received in-home and laboratory-based assessments of their demographic, clinical, functional, and cognitive characteristics. Falls data were collected by having participants return monthly postcards on which they recorded whether or not they fell on a given day. Subjects who failed to return the postcards were contacted by telephone to determine their fall status. The MBS design and methods have been reported previously [12].

In this study, eighteen elderly non-fallers (17 female and 1 male; age range, 71–91 years; mean age, 77 ± 4 years) were matched by age (with an average difference of 3 ± 2 years), gender, and body mass index to 18 recurrent fallers (17 female and 1 male; age range, 72–88 years; mean age, 78 ± 5 years; Table 1). Recurrent fallers were defined as participants with two or more falls reported prospectively over twelve months in the MBS study. Elderly non-fallers were defined as participants enrolled for at least 12 months in MBS without any reported falls.

Table 1.

Elderly Nonfaller and Recurrent Faller Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Elderly Nonfallers (n=18) |

Elderly Recurrent Fallers (n=18) |

P- Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 77 ± 4 | 78 ± 5 | .97 |

| Gender, % female | 94 (n = 17) | 94 (n = 17) | 1.00 |

| Race, % Non-white | 22 (n = 4) | 22 (n = 4) | 1.00 |

| Height, meters | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | .80 |

| Weight, kg | 71.9 ± 12.9 | 70.8 ± 14.4 | .82 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 27.6 ± 5.1 | 27.3 ± 4.5 | .89 |

| Hypertension (diagnosed), % | 50 (n = 9) | 56 (n = 10) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes (diagnosed), % | 6 (n = 1) | 17 (n = 3) | .29 |

| Previous falls/12+ months | 0 | 3 ± 1 | <.001 |

| Gait Speed (4m walk), m/s | 1.06 ± 0.24 | 1.08 ± 0.29 | .81 |

| Instrumental Activity of Daily Living, % with little, some, or major difficulty | 33 (n = 6) | 28 (n = 5) | .72 |

| Double Leg Press, Watts (Power) | 527 ± 186 | 453 ± 162 | .25 |

| Mini Mental State Examination Score (range, 0–30; 0 = poor cognition, 30 = good cognition) [13] | 28.1 ± 2.1 | 28.3 ± 1.3 | .64 |

| Trail-Making Test B*, seconds (range, 0–600; 0 = good executive function, 600 = poor executive function) [14] | 146 ± 100 | 106 ± 42 | .13 |

| Decreased Sensation**, % | 11 (n = 2) | 11 (n = 2) | 1.00 |

Trail-Making Test B is a benchmark test of executive function that requires the connection of circles marked by numbers and letters in alternating sequence [14].

Participants were classified as having decreased sensation based on feeling less than 3 monofilament touches for both a 4.17- and 5.07-gram monofilament on the left or right great toe [15].

We excluded individuals with foot ulcers, a history of stroke or fainting, a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) below 23 [13,14], the inability to walk unassisted, or a shoe size unavailable in the vibrating sandals. Elderly recurrent fallers were screened by a neurologist to exclude those with any specific neurological deficits resulting from neuropathy, neuromuscular disorders or spinal stenosis. We excluded subjects with clinical evidence of peripheral neuropathy because we would be unable to determine a sensory threshold and set noise levels appropriately.

Twelve young subjects (7 female and 5 male; mean age, 26 ± 5 years, range 20–34) were recruited from Boston University and the Hebrew Rehabilitation Center. The young group was included as a reference group for the elderly fallers and non-fallers. Since it is not known to what extent a reduction in gait variability would reduce fall risk, we assumed that a reduction to the level of healthy young subjects would be clinically meaningful.

All participants provided informed consent as approved by the Hebrew SeniorLife Institutional Review Board (protocol number 04–011). This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00421759.

Sandals

Custom sandals were developed to deliver subsensory mechanical noise vibrations to the soles of the feet. Three vibrating actuators (C-2, Engineering Acoustics; Winter Park, FL) were fastened into wells in the soles of the sandals, allowing vibrations to propagate to the plantar foot surface. The delivered signal was Gaussian white noise, band-limited to 100 Hz. Two force sensing resistors (FSRs) (Interlink Electronics; Camarillo, CA) were attached to the surface of the sandal under the calcaneus and metatarsals of the foot to detect pressure during walking. In order to reduce the potential for discomfort and non-characteristic gait, women’s and men’s sandals were provided in a variety of different shoe sizes.

A custom circuit and LabView program (National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX) were developed to process pressure signals and deliver appropriate noise signals. The pressure signals were filtered and amplified so that they could act as a footswitches during walking. Vibrations were produced by sending the noise signal (maximum 3.5 Volts, 0.5 Amps, RMS) to the actuators.

Threshold Settings

Prior to data collection, a sensory threshold test was conducted on each participant. As sensory thresholds are pressure dependent, this exercise was performed during three separate postural configurations: two-legged standing, one-legged standing, and sitting with feet raised above the floor. These configurations reflect the different phases that occur during the normal gait cycle: double-support, single-support, and swing phase, respectively. Although there may be a difference between thresholds during static and dynamic loading (i.e. walking) conditions, the standing and sitting threshold settings were intended to mirror the dynamic walking cycle as closely as possible.

The noise amplitude of the vibrating sandals was adjusted to determine the sensory threshold. Noise amplitudes were set to 90% of this threshold for each phase, a level previously found to be effective in reducing sway [2–5]. For subjects unable to perceive the vibration at its maximum amplitude, the level was set to the equipment’s upper limit. These subjects might have had sub-clinical neuropathy. As some sensation remained intact as evidenced by the neurological screening and monofilament test, it was assumed that these participants could potentially benefit from the vibrations. Throughout the testing, the noise signal remained subthreshold, keeping all subjects blind to the noise condition.

A feedback system was implemented to collect pressure data and deliver the appropriate 90% subsensory noise signal during walking. A LabVIEW program determined the phase of each foot (two-legged, one-legged, or swing) based on the pressure signal, sampled at 1000 Hz, and then sent the matching noise signal amplitude to the actuators.

Protocol

Subjects were fitted with a pair of vibrating sandals and required to walk around a 23-meter elliptical track. The actuators were powered through a cable that extended from a rotating electrical connector in the laboratory ceiling to a belt on the subject’s waist, then to the sandals. Subjects were barefoot in the sandals and dressed comfortably.

Subjects completed three six-minute walking trials, during which the noise signal was applied for half of each trial. The stimulation condition was randomized to occur in the first or second half of each trial. Subjects were instructed to walk normally and to stop if they felt tired or uncomfortable. A one-minute practice trial was conducted for each subject to ensure proper fit of the sandals. Prior to data collection, the subject walked for twenty seconds in order to avoid transient start-up effects. After walking for three minutes, the system automatically switched between the noise or no-noise condition. Following each trial, subjects were asked to report if they felt the vibration at any point and to comment on their comfort. Vibrations were not felt by any subjects, no trials were stopped due to discomfort, and no significant discomfort was reported.

Average gait speed was calculated from the distance traveled during each three-minute walking period. Distance was determined from the track segments traversed (the track has 12 equal segments, each 1.9 meters in length). After each trial, the subject rested for two minutes.

Data Processing

Pressure data from the FSRs during walking were analyzed to identify heel-strike and toe-liftoff events. These events were used to calculate the timing of stride, stance, and swing phase gait intervals [11]. When outlier interval values were observed, the pressure signal was inspected visually. In all cases, these outlier points were confirmed to correspond to noise in the signal rather than a gait-driven pressure response. As participants were closely observed during the trials and no stumbles were recorded, we could ascertain that these points did not reflect “near falls.” A median-based non-sliding window filter was applied to remove the outliers that lay three standard deviations above or below the median. This procedure was performed separately for noise and no-noise conditions and resulted in the removal of less than 1% of the data in each instance.

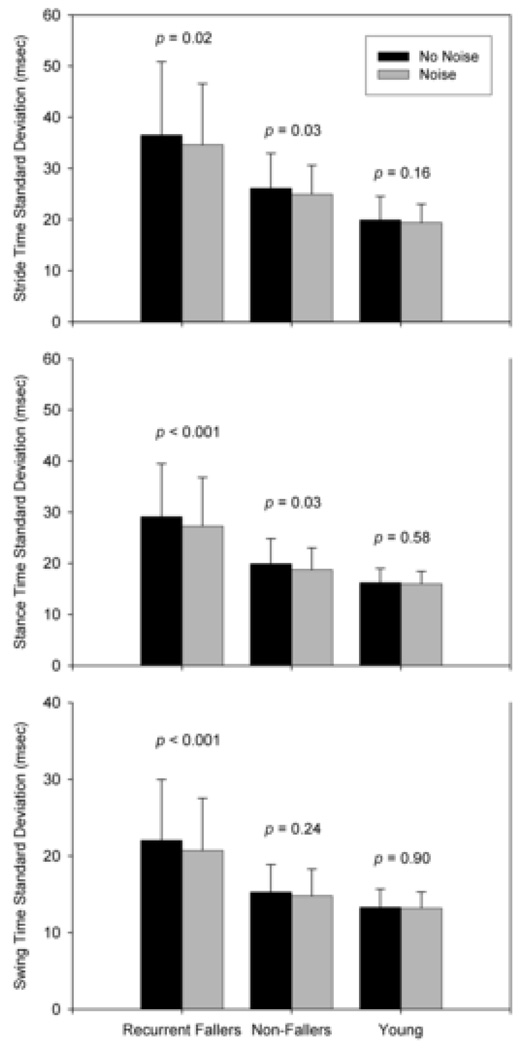

Although subjects were instructed to maintain a comfortable and constant pace while walking, drifts in gait timing intervals due to decreases in gait speed were noted in elderly subjects. To remove drifts in interval data, a second order Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter was applied to the original signal, generating a second order polynomial. This resulting polynomial was subtracted from the original signal as seen in Figure 1. With this technique, high frequency components of the signal are preserved while low frequency drift is eliminated. The gait intervals become zero-meaned, and the standard deviation of intervals is the primary measure for assessing variability.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a illustrates the raw stride interval data during walking. By applying a smoothing filter to the original signal, a second order polynomial is generated. By subtracting this polynomial from the original signal (1a), the low frequency trend is removed and the high frequency variability remains (2a).

Statistics

A linear mixed effects analysis of variance model was used to analyze the effect of noise on gait variability. In this model, gait variability was the dependent variable. Each subject had 6 measurements, 3 with noise and 3 without noise, corresponding to the three 6 minute trials. The effects of 1) stimulation (noise, no-noise), 2) group (young, non-fallers, recurrent fallers), and 3) the interaction of group×stimulation were examined.

This statistical model included trial order as a covariate to account for effects of fatigue between trials and included gait speed as a covariate, as speed may affect gait variability [15]. As body size can affect gait variability and gait speed, body size corrections were made to these measures to allow for better between-subjects comparisons. To scale gait-related data to body size, gait variability measures (in units of time) were divided by , and gait speed measures (in units of length/time) were divided by , where l is height, and g is gravity (9.81 m/s2) [16].

As elderly participants were well matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI), adjustments for age, sex, and BMI were not made. Including BMI as a covariate to account for possible differences between elderly and young did not affect the results, and therefore BMI was not included in the final multivariate model. To account for multiple observations per person, an unstructured within-subjects covariance matrix was used.

Standard errors were estimated using the empirical (“sandwich”) method. Tukey Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc tests were used to compare variability differences between the noise and no-noise conditions within each group. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

As some subjects were unable to perceive the vibration to set thresholds for certain configurations, we assessed whether the ability to deliver a 90% subthreshold vibration affected the results. Analysis was performed with a general linear model in which the number of missing thresholds (0–6) was the independent variable, and the difference in gait variability between the noise and no-noise condition was the dependent variable. Age and gender were also included as covariates in the model. We did not find a difference between those with differing numbers of missing thresholds for the stride (P = 0.904), stance (P = 0.277), and swing (P = 0.387) interval.

RESULTS

Group characteristics for the elderly subjects are shown in Table 1. Fallers and non-fallers were well matched on age, BMI, and sex. The two groups exhibited similar levels of activity, sensation, and cognitive function [13,14]. Young subjects were not fully assessed for clinical characteristics, but had a mean height of 1.7 ± 0.2 meters, a mean weight of 66.3 ± 18.2 kg, and a mean BMI of 22.8 ± 4.4 kg/m2.

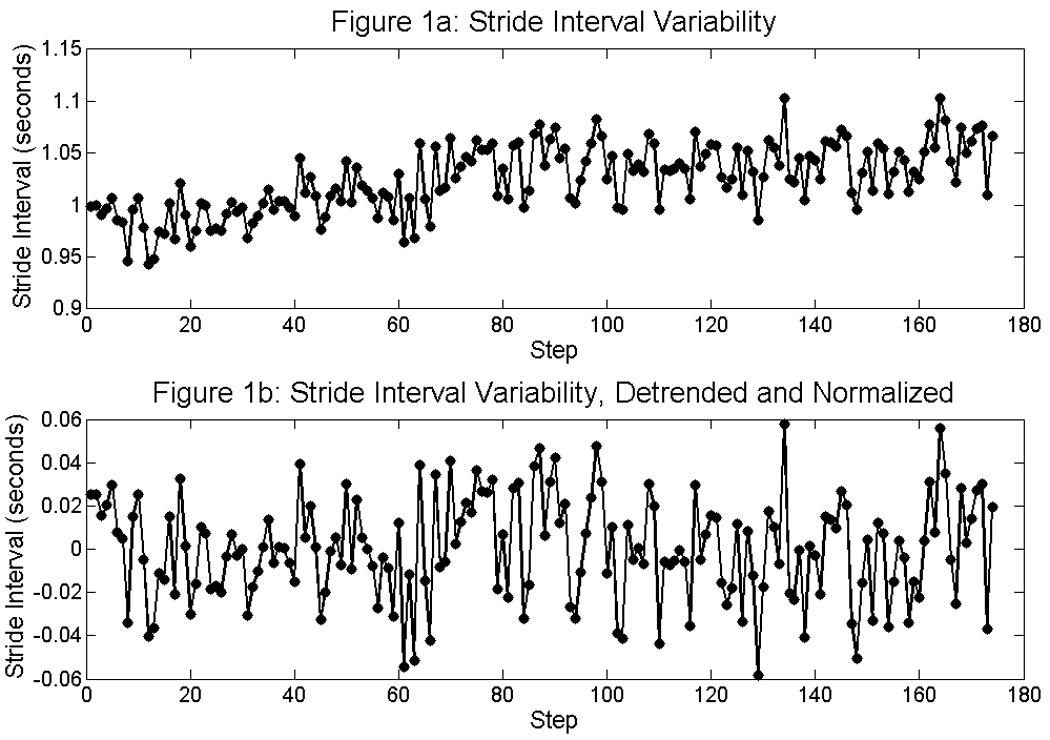

In elderly recurrent fallers, baseline stride, stance, and swing time variability were 37 ± 14 ms, 29 ± 10 ms, and 22 ± 8 ms respectively. Compared to elderly fallers, non-fallers had lower baseline variability for stride (26 ± 7 ms, t45 = −3.07, P = 0.004), stance (20 ± 5 ms, t45 = −4.37, P < 0.001), and swing (15 ± 4 ms, t45 = −3.67, P < 0.001) phases. Baseline variability measures were lowest for the young control group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Group means and standard deviations of gait timing interval variability are presented for “no-noise” (black bars) and “noise” (gray bars) conditions. The P-values for the effect of noise within each group are shown above the bars.

The effect of noise stimulation was significant for all mean gait variability measures (stride F1,45 = 9.85, P = 0.003; stance F1,45 = 13.60, P < 0.001, and swing F1,45 = 7.40, P = 0.009). Stratifying by group, elderly recurrent fallers demonstrated reductions for mean stride (t45 = 2.43, P = 0.02), stance (t45 = 3.96, P < 0.001), and swing (t45 = 3.89, P < 0.001) time variability. Elderly non-fallers exhibited a significant reduction for the stride (t45 = 2.31, P = 0.03) and stance variabilities (t45 = 2.29, P = 0.03). Although the young group tended to reduce mean gait variability for all timing intervals, this result did not reach statistical significance.

Mean gait variability measures for individual subjects (elderly fallers and non-fallers) during noise and no-noise conditions are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. We were initially concerned that a few subjects might be driving the averaged gait variability reductions. However, these data show small reductions in gait variabilities for most subjects; 72%, 78%, and 78% of recurrent fallers and 78%, 83%, and 56% of non-fallers exhibited reductions for the stride, stance, and swing time variability respectively.

Table 2.

Gait Variability Measures for Elderly Fallers

| Subject | Stride (ms) | Stance (ms) | Swing (ms) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | No Noise | Noise | No Noise | Noise | No Noise | Noise |

| 1 | 52.0 | 47.7 | 37.3 | 37.6 | 31.1 | 27.4 |

| 2 | 68.5 | 57.2 | 49.5 | 42.9 | 39.1 | 35.7 |

| 3 | 24.6 | 23.7 | 19.3 | 18.2 | 10.4 | 10.9 |

| 4 | 25.2 | 24.5 | 18.8 | 17.6 | 14.8 | 13.8 |

| 5 | 43.5 | 41.3 | 37.3 | 32.1 | 30.1 | 27.6 |

| 6 | 16.2 | 18.3 | 16.9 | 17.8 | 16.6 | 15.5 |

| 7 | 38.1 | 38.4 | 31.1 | 30.5 | 27.6 | 25.1 |

| 8 | 49.8 | 47.4 | 33.5 | 30.8 | 27.3 | 27.6 |

| 9 | 21.9 | 22.8 | 18.5 | 17.6 | 13.5 | 13.6 |

| 10 | 35.8 | 33.0 | 28.2 | 25.9 | 20.2 | 19.5 |

| 11 | 30.0 | 27.9 | 31.0 | 25.5 | 24.3 | 22.4 |

| 12 | 53.4 | 45.7 | 34.8 | 29.6 | 27.8 | 25.0 |

| 13 | 19.4 | 22.1 | 13.4 | 14.9 | 11.9 | 13.3 |

| 14 | 30.6 | 29.5 | 31.6 | 30.0 | 17.7 | 17.1 |

| 15 | 33.0 | 29.7 | 24.7 | 24.1 | 18.8 | 17.1 |

| 16 | 49.0 | 47.9 | 37.3 | 36.6 | 27.7 | 24.7 |

| 17 | 21.8 | 20.6 | 15.9 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 13.1 |

| 18 | 44.7 | 46.1 | 44.5 | 45.5 | 24.1 | 23.5 |

| Avg. | 36.5 | 34.7 | 29.1 | 27.3 | 22.0 | 20.7 |

| Std. Dev. | 14.3 | 11.9 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 7.9 | 6.8 |

Table 3.

Gait Variability Measures for Elderly Non-fallers

| Subject | Stride (ms) | Stance (ms) | Swing (ms) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | No Noise | Noise | No Noise | Noise | No Noise | Noise |

| 1 | 25.4 | 22.2 | 18.3 | 15.6 | 13.7 | 14.5 |

| 2 | 18.9 | 21.5 | 16.1 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 10.1 |

| 3 | 21.9 | 22.6 | 19.4 | 18.7 | 14.8 | 15.1 |

| 4 | 27.8 | 27.2 | 21.3 | 20.4 | 15.5 | 14.0 |

| 5 | 27.6 | 27.9 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 15.6 | 16.0 |

| 6 | 22.8 | 23.4 | 14.3 | 16.3 | 16.1 | 16.5 |

| 7 | 45.9 | 40.3 | 34.7 | 30.2 | 22.6 | 20.9 |

| 8 | 21.5 | 20.5 | 20.1 | 17.5 | 18.7 | 16.7 |

| 9 | 24.3 | 24.2 | 18.8 | 17.2 | 13.5 | 13.0 |

| 10 | 28.1 | 26.4 | 19.4 | 19.9 | 16.8 | 16.6 |

| 11 | 19.8 | 18.7 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 12.3 |

| 12 | 25.3 | 23.7 | 21.0 | 20.3 | 14.9 | 16.4 |

| 13 | 19.8 | 18.4 | 15.7 | 14.1 | 11.0 | 11.0 |

| 14 | 33.7 | 31.9 | 24.9 | 24.9 | 23.1 | 23.3 |

| 15 | 24.7 | 22.8 | 19.6 | 17.4 | 12.9 | 12.2 |

| 16 | 24.4 | 23.5 | 20.1 | 19.4 | 11.6 | 11.4 |

| 17 | 37.0 | 34.0 | 25.4 | 23.6 | 17.8 | 16.0 |

| 18 | 21.3 | 19.9 | 18.4 | 16.9 | 10.0 | 10.4 |

| Avg. | 26.1 | 24.9 | 19.9 | 18.8 | 15.3 | 14.8 |

| Std. Dev. | 6.8 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

Walking speeds between elderly fallers (0.93 ± 0.23 m/s) and non-fallers (1.00 ± 0.15 m/s) were similar (t45 = 1.12, P = 0.27), yet fallers had more gait variability. In considering all subjects, the application of noise did not affect gait speed (F1,45 = 1.76, P = 0.19). There was no significant interaction between noise stimulation and group (fallers vs. non-fallers) for stride or stance gait variabilities (stride t45 = 0.11, P = 0.92; stance t45 = 1.21, P = 0.23), but there was a marginally significant interaction for the swing interval variability (t45 = 1.99, P = 0.053), such that recurrent fallers had the greater effect.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the ability of sub-sensory mechanical noise delivered to the soles of the feet through vibratory sandals to reduce stride, stance, and swing time variability in elderly fallers. This study supports the concept that mechanical noise may improve gait dynamics in individuals at high risk of falls.

As increased gait variability is a predictor of falls [9–11], the effect of noise in reducing variability may be beneficial. Fallers and non-fallers have greater gait variability than the young, as they are older, frailer, and in turn may not have the same intact sensory and motor function. The fallers showed greater variability than the non-fallers suggesting that variability may be associated with falls.

The application of noise did not affect gait speed, which suggests that this intervention was not mediated through differences in speed. The average effect size for gait variability was approximately 6%. The vibrating sandals improved gait variability in fallers, but they did not reduce variability levels in elderly recurrent fallers to the baseline range of elderly non-fallers or young controls.

A recent report suggested that stance time variability in a similar cohort of 379 elderly subjects was a significant predictor of mobility disability [17]. There was an 11% difference in stance time variability between subjects with and without onset of mobility disability. With the vibrating insoles, 6.3% and 5.8% reductions were observed in stance time variability for the recurrent faller and non-faller groups, respectively. Therefore the vibrating sandals may have achieved half of the effect required to reduce onset of mobility disability. As we have previously shown an additional effect of vibrating insoles on improving static balance [3–5], it is possible that the combined effect on balance and gait will have a greater impact on falls and mobility than our data would imply. This hypothesis needs to be tested in future clinical trials. Furthermore, since the etiology of falls is often multi-factorial, an intervention that produces a small improvement in one risk factor may have a multiplicative effect when used in combination with other interventions. Alternatively, given the multi-factorial nature of falls, a change in gait variability alone may not be able to overcome the effect of other pathologies or risk factors.

Our study has several limitations. As the vibrating sandals were a simple prototype, a different design may elicit greater reductions in gait variability. By implementing more actuators and FSRs, a more sensitive pressure distribution map of the foot could be developed and used to locally adjust the amplitude of each individual actuator. In this way, maximum signal transmission would be achieved across the entire sole of the foot. Due to the power limitations of the insoles, some subjects could not perceive the vibration at its maximum amplitude for particular threshold configurations. For these cases, the noise amplitude was set to a default maximum value. As a result, participants may have received mechanical vibrations below 90% of their sensory threshold. The benefit was still observed, but perhaps not to the degree that might have been achieved with a true 90% threshold setting.

In summary, we have shown that subsensory vibratory noise applied to the soles of the feet during the gait cycle can reduce gait variability in elderly fallers. We hope this work stimulates the development of portable insoles that can be tested for their effect on falls in large elderly populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (Bethesda MD): Research Nursing Home Program Project P01AG004390 and Training Grant T32AG023480. The authors acknowledge the MOBILIZE Boston research team and study participants for the contribution of their time, effort, and dedication. We also thank James Collins, PhD, Dan Kiely, Jared Bancroft, and Ioana Lupascu for their work on this project.

Sponsor’s Role:

The funding sources had no role in the design, methodology, data acquisition, or preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. D’Andrea was an employee of Afferent Corporation, which was developing the technology for commercial use. Dr. Priplata holds a patent for the subsensory vibration technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoyert DL, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 1997. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1999;47:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins JJ, Priplata AA, Gravelle DC, Niemi J, Harry J, Lipsitz LA. Noise-enhanced human sensorimotor function. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2003;22:76–83. doi: 10.1109/memb.2003.1195700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priplata AA, Niemi JB, Harry JD, Lipsitz LA, Collins JJ. Vibrating insoles and balance control in elderly people. Lancet. 2003;362:1123–1124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priplata A, Niemi J, Salen M, Harry J, Lipsitz LA, Collins JJ. Noise-enhanced human balance control. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priplata AA, Patritti BL, Niemi JB, Hughes R, Gravelle DC, Lipsitz LA, Veves A, Stein J, Bonato P, Collins JJ. Noise-enhanced balance control in patients with diabetes and patients with stroke. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:4–12. doi: 10.1002/ana.20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins JJ, Chow CC, Imhoff TT. Aperiodic stochastic resonance in excitable systems. Phys Rev E Stat Phys Plasmas Fluids Relat Interdiscip Topics. 1995;52:R3321–R3324. doi: 10.1103/physreve.52.r3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiesenfeld K, Moss F. Stochastic resonance and the benefits of noise: from ice ages to crayfish and SQUIDs. Nature. 1995;373:33–36. doi: 10.1038/373033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang HG, Dingwell JB. A direct comparison of local dynamic stability during unperturbed standing and walking. Exp Brain Res. 2006;172:35–48. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausdorff JM, Edelberg HK, Mitchell SL, Goldberger AL, Wei JY. Increased gait unsteadiness in community-dwelling elderly fallers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausdorff JM, Peng CK, Goldberger AL, Stoll AL. Gait unsteadiness and fall risk in two affective disorders: a preliminary study. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausdorff JM. Gait variability: methods, modeling and meaning. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2005;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leveille SG, Kiel DP, Jones RN, Roman A, Hannan MT, Sorond FA, Kang HG, Samelson EJ, Gagnon M, Freeman M, Lipsitz LA. The MOBILIZE Boston Study: Design and methods of a prospective cohort study of novel risk factors for falls in an older population. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan K, Challis JH, Newell KM. Walking speed influences on gait cycle variability. Gait Posture. 2007;26:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hof AL. Scaling Gait Data to Body Size. Gait Post. 1996;4:222–223. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brach JS, Studenski SA, Perera S, VanSwearingen JM, Newman AB. Gait variability and the risk of incident mobility disability in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:983–988. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]