Abstract

Phosphopeptide identification and site determination are major challenges in biomedical MS. Both are affected by frequent and often overwhelming losses of phosphoric acid in ion trap CID fragmentation spectra. These losses are thought to translate into reduced intensities of sequence informative ions and a general decline in the quality of MS/MS spectra. To address this issue, several methods have been proposed, which rely on extended fragmentation schemes including collecting MS3 scans from neutral loss-containing ions and multi-stage activation to further fragment these same ions. Here, we have evaluated the utility of these methods in the context of a large-scale phosphopeptide analysis strategy with current instrumentation capable of accurate precursor mass determination. Remarkably, we found that MS3-based schemes did not increase the overall number of confidently identified peptides and had only limited value in site localization. We conclude that the collection of MS3 or pseudo-MS3 scans in large-scale proteomics studies is not worthwhile when high-mass accuracy instrumentation is used.

Keywords: Mass accuracy, MS3, Neutral loss, Phosphorylation

1 Introduction

Reversible protein phosphorylation of serine, threonine and tyrosine regulates almost every aspect of eukaryote cellular life. Signals from the extracellular environment are propagated by means of multiple and orchestrated phosphorylation events, to finally control gene expression, protein translation and cell division, among others. These phosphorylation events have long attracted the attention of cell biologists, who have widely studied such processes by mutation studies, kinase or phosphatase assays and 32P-radiolabeling techniques, usually at the single-protein level. Recently, emerging MS techniques have allowed for large-scale studies of simultaneous phosphorylation events occurring under specific conditions including disease.

The capacity of studying thousands of phosphorylation sites in a single experiment has only been realized within the past few years. In our first large-scale phosphorylation study [1], we found that one significant difficulty in large-scale phosphopeptide analysis was the frequent and often over-whelming domination of phosphorylation-specific neutral losses (NL) in MS/MS (MS2) spectra collected in a 3-D IT. These peaks are the result of the β-elimination of phosphoric acid from phosphoserine and phosphothreonine residues, reducing the intensity of backbone b- and y-type ions that are critical for both phosphopeptide identification and precise site localization. To address this issue, we introduced a new data-dependent neutral loss (DDNL) MS3 method [1, 2] that consisted of additional fragmentation of the product of the precursor neutral loss in the form of an MS3 scan. To avoid expending extra time when MS2 contained sufficient information, this scan was only initiated when a dominant NL-associated peak was detected in the MS2 spectrum. We found this approach to be useful in 3-D IT where relatively small numbers of ions made up the detected MS2 spectrum and accurate masses were not known. This approach has now been widely adopted for both phosphorylation analysis [1, 3–6] and in its more general data-dependent MS3 version for protein analysis [7].

In addition to the DDNLMS3 method, another approach was developed by Coon, Hunt and colleagues [8], which consistently used a supplemental activation of the NL product and recorded all the fragments in the same MS2 scan (pseudo MS3). This method has also been favorably used in at least one large-scale phosphorylation study [9]. Both methods, at the expense of extra analysis time, are able to collect data with potentially increased spectral quality.

Although each method has been successfully demonstrated, in recent years IT mass spectrometers have evolved toward linear (2-D) IT capable of collecting MS2 spectra at faster scan rates and with increased sensitivity [10]. These may provide sequence-informative fragmentation even with concomitant NL observations. Furthermore, linear IT have been interfaced with additional mass analyzers (ICR cell [11] or Orbitrap [12]) capable of high-resolution and high-mass accuracy measurements, which, applied to precursor ion detection, increase the confidence in phosphopeptide identifications [13] and may obviate MS3 collection. Here, we decided to re-evaluate the utility of both MS3 methods in combination with high-mass accuracy instrumentation in large-scale phosphoproteomics studies, and estimate an ideal compromise between the extra-time consumed in those MS3 scans and the additional information gained in the context of shotgun phosphopeptide sequencing.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample preparation

Budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae was grown to mid-log phase. Cells were collected and pelleted by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 30 min, 4°C), rinsed with water and lysed by bead-beating at 4°C (4 cycles of 90 s, with 60-s rest in between) in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 8.2, 8 M urea, 75 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate and one tablet protease inhibitors cocktail (complete mini, EDTA-free, Roche) per 10 mL. The protein extract was separated from the beads and insoluble material. Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce).

Ten milligrams of protein was subjected to disulfide reduction with 5 mM DTT (56°C, 25 min) and alkylation with 15 mM iodoacetamide (room temperature, 30 min in the dark). Excess of iodoacetamide was captured with 5 mM DTT (room temperature, 15 min in the dark). Protein was digested in solution with 5 ng/µL trypsin in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.5 M urea, at 37°C for 15 h.

Peptide mixtures were acidified with TFA to 0.2%, clarified by centrifugation and desalted in a 200 mg tC18 SepPak cartridge (Waters) as previously described [14].

Peptides were separated into 11 fractions by strong-cati-on exchange (SCX) chromatography as described [14].

For IMAC phosphopeptide enrichment, desalted phosphopeptides were dissolved in 120 µL of IMAC-binding buffer [40% ACN, 25 mM formic acid (FA)] and incubated for 60 min with 10 µL PhosSelect IMAC resin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) previously equilibrated with the same buffer. Resin was washed three times with 120 µL IMAC-binding buffer and peptides were eluted with 3 × 70 µL 50 mM KH2PO4/NH3 pH 10.0. Peptides were acidified with FA, dried and desalted with C18 Empore disks.

2.2 MS

Dried phosphopeptides were resuspended in 15 µL 5% ACN, 4% FA, and 1.5 µL was loaded onto a microcapillary column packed with C18 beads (Magic C18AQ, 5 µm, 200Å, 125 µm × 18 cm) using a Famos autosampler (LC Packings). Peptides were separated by RP chromatography using an Agilent 1100 binary pump across a 60-min gradient of 7–28% ACN (in 0.125% FA) and online detected in a hybrid linear IT – Orbitrap (LTQOrbitrap, Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA) mass spectrometer using a data-dependent TOP10 method [15]. For each cycle, one full MS scan in the Orbitrap at 1 × 106 AGC target was followed by ten MS/MS (MS2) in the LTQ at 5000 AGC target on the ten most intense ions. Selected ions were excluded from further selection for 35 s. Ions with charge 1 or unassigned were also rejected. Maximum ion accumulation times were 1000 ms for full MS scan and 120 ms for MS2 scans.

For the DDNLMS3 method, an MS3 was triggered if in the MS2 a neutral loss peak at −49, −32.7 or −24.5 Da was observed and that peak was one of the two most intense ions of the MS2 spectrum. MS3 accumulation times and AGC target were the same as for MS2 scans. For the pseudo MS3 method [8], multi-stage activation was targeted at −49, −32.7 and −24.5 Da from the selected precursors using 1.0-Da mass width.

2.3 Database searches and data filtering

RAW files were converted to the mzXML file format and imported into a relational MySQL database. Data analysis was performed using in-house software. For the DDNLMS3 method, MS2 spectra and MS3 spectra were treated separately for searches and filtering. MSn spectra were searched against a target-decoy [16] S. cerevisiae ORF database using the SEQUESTalgorithm (version 27, revision 12), with either 50 ppm or 2 Da precursor mass tolerance, tryptic enzyme specificity with two missed cleavages allowed and static modification of cysteines (+57.02146, carboxamidomethylation). Dynamic modifications for MS2 and pseudo MS3 spectra were 79.96633 Da on Ser, Thr and Tyr (phosphorylation) and 15.99491 Da on Met (oxidation), for MS3 spectra −18.01056 Da on Ser and Thr (loss of phosphoric acid from the phosphorylated residue to produce a di-dehydroamino acid) was also included. In addition, for pseudo MS3 spectra, neutral losses from b- and y-type ions were considered. XCorr and dCn’ [14] score cut-offs, mass deviation (in ppm) and peptide solution charge were empirically determined for the combined spectra of same kind (MS2, MS3 or pseudoMS3) using decoy matches as a guide [16] and aiming to maximize the number of peptide spectral matches while maintaining an estimated false-discovery rate (FDR) of ≤1%. Searches at 50 ppm precursor mass tolerance were filtered using mass accuracy information (set from −4 to +2 ppm), XCorr 1.2, 1.5 and 2.4 for 2+, 3+ and 4+, respectively, and dCn’ >0.04. Where indicated, searches using 2 Da precursor mass tolerance were performed (with no mass accuracy filtering) to simulate low-mass accuracy data such as that acquired on a stand-alone LTQ. The filters required in this case were XCorr 2.1, 2.5 and 3.1 for 2+, 3+ and 4+, respectively, and dCn’ >0.12. In both cases, solution charges +1, +2 and +3 were included. Due to considering an increased number of theoretical ions, the pseudo MS3 method required more stringent XCorr and dCn’ filters.

In order to accurately represent the impact of NL fragment ions on an entire phosphorylation analysis, data from all fractions were used for determining the occurrence of NL fragmentation (Fig. 1A) using the TOP10 method. However, for clarity, only fraction #5 run was chosen for all other aspects of this study (Fig. 1B–G, Fig. 2–Fig. 6).

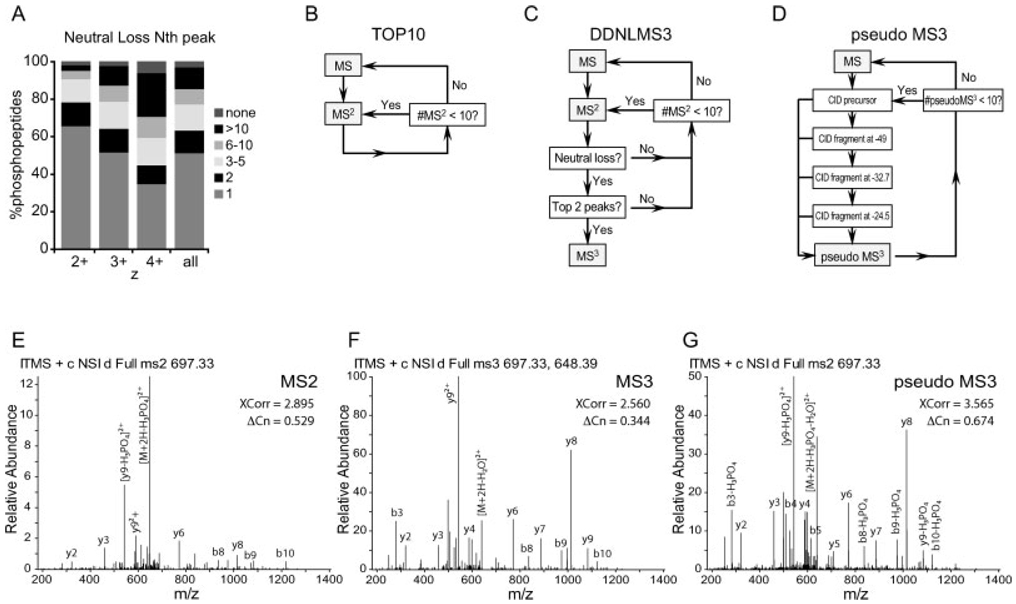

Figure 1.

(A) Neutral loss fragment ion frequency in ion trap CID MS2 spectra from identified phosphopeptides. Proteolyzed yeast protein (10 mg) was separated by SCX chromatography. Eleven collected fractions were subjected to phosphopeptide enrichment using IMAC. Each fraction was analyzed by LC-MS/MS using the TOP10 method and spectra were assigned using SEQUEST. From 19 087 identified phosphopeptides, the intensity rank (Nth) of the peak corresponding to neutral loss of phosphoric acid (−49 for 2+, −32.7 for 3+ and −24.5 for 4+) was plotted in relation to the charge of the precursor ion. Neutral loss was a very common event in IT spectra. The lability of the phosphate group was charge dependent, being more stable at higher charge states. (B) Scheme for the scan cycles in the TOP10 MS2 method: on each cycle, one MS scan was followed by ten MS2 scans. (C) Scheme for the scan cycles in the data-dependent neutral loss MS3 (DDNLMS3) method: one MS scan was followed by ten MS2 scans. EachMS2 was interrogated by the presence of a neutral loss peak and by its intensity rank in the spectrum. If both conditions were satisfied, an MS3 scan was triggered. (D) Scheme for the scan cycles in the pseudo MS3 method: one MS scan was followed by ten MS2 scans. Each MS2 was collected only after additional activation of fragment ions at −49, −32.7 and −24.5 mass units from the parent ion, corresponding to neutral losses of phosphoric acid. (E–G) Examples of spectra corresponding to the same doubly charged ion for the phosphopeptide, VIS*QDALQHFR, from GTPase Nog2, (E) an MS2 spectrum, (F) an MS3 spectrum, (G) a pseudo MS3 spectrum. Note different y-axis scale for a better representation of fragment ion populations.

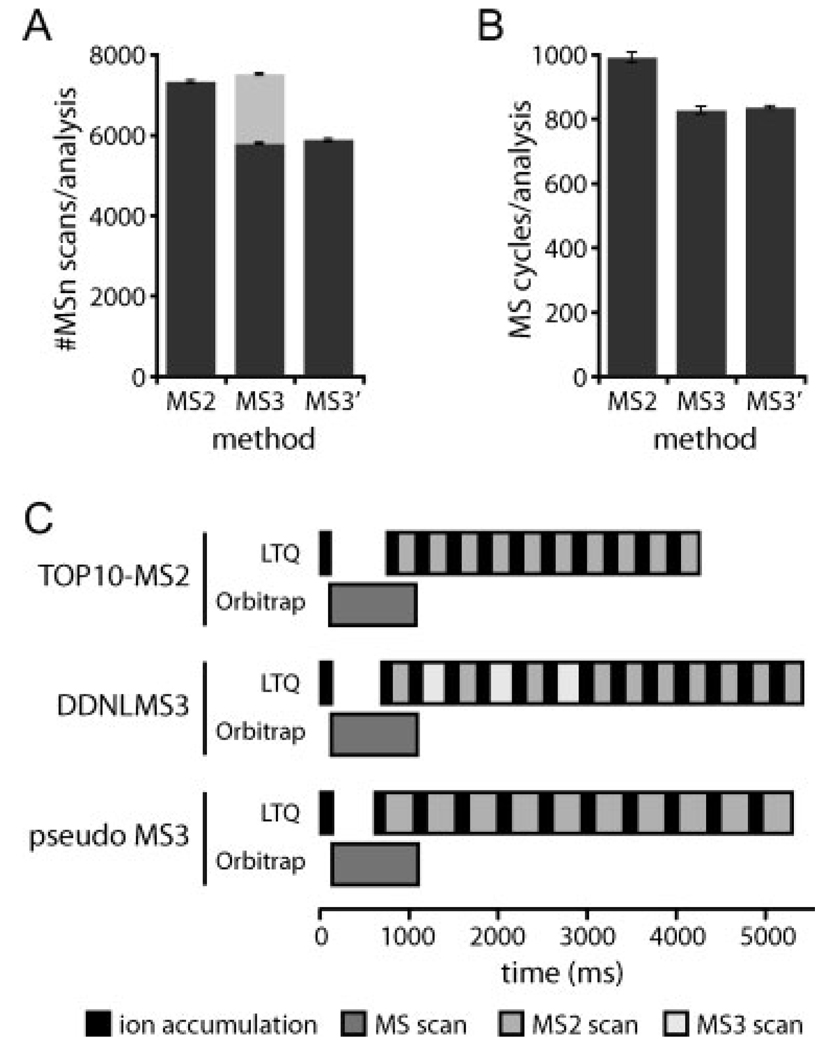

Figure 2.

Scan collection and scan cycle schemes for MS2 and MS3 methods. (A) Number of MSn scans collected and (B) number of scan cycles for the TOP10 MS2 (MS2), DDNLMS3 (MS3), and pseudo MS3 (MS3′) methods. Values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate analyses of a single SCX fraction (fraction #5) for each method. MS2 or pseudo MS3: dark, MS3: pale grey. (C) Average cycle times for the data acquisition methods used in this study. All scan times were calculated directly from the acquired data for each method. Ion accumulation times and scan times for full MS scan, as well as total scan cycle times were calculated from cycles were ten dependent MS2 scans, ten MS2 and three MS3 scans or ten pseudo MS3 were collected, which corresponded to the median numbers of scans per cycle for each method, respectively. Ion accumulation periods are shown in black, while analysis periods are shown in grey scale for the different scan types.

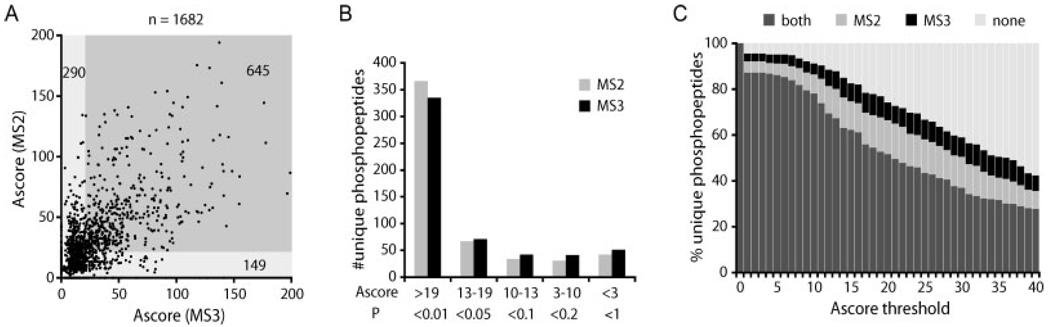

Figure 6.

Site localization comparison for MS2–MS3 pairs. (A) Scatter plot of each MS2–MS3 same-sequencematching pair. Rarely does an MS2 spectrum receive a score <19, which is rescued by a score >19 in the MS3 spectrum (pale grey bottom-right box; 9%). (B) Distribution of binned Ascore values for MS2 and MS3 spectra. (C) Cumulative distribution of unique phosphopeptides matches passing as a function of Ascore values. On their own, MS2 spectra produce relatively higher Ascore values than MS3.

2.4 Phosphorylation-site localization

Identified phosphopeptides passing our filtering criteria were submitted to the Ascore algorithm [17] for precise site localization. Minor modifications of the basic software were performed to accommodate site localization for MS3 and pseudo MS3 spectra. For MS3, the −18.01056 Da modification was also permutated. For fragments from pseudo MS3 spectra, products of neutral loss from b- and y-type ions were also taken into account.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 How prevalent are phosphorylation-specific neutral loss events?

To assess the frequency of these NL fragmentation events, we performed a large-scale phosphorylation experiment. Whole-cell yeast extract was proteolyzed with trypsin and subjected to first separation by SCX chromatography. Eleven fractions were collected, enriched for phosphopeptides using IMAC and analyzed in a hybrid linear IT – Orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQOrbitrap). From 59 727 MS2 scans collected, 19 087 (32%) were matched to phosphopeptide sequences at an estimated FDR of less than 1% (4801, 2+; 9865, 3+; 4421, 4+). These spectra were examined for the presence of intense fragment ions derived from the neutral loss of phosphoric acid (−49 for 2+, −32.7 for 3+ and −24.5 for 4+). As shown in Fig. 1A, phosphate-associated NL is a very frequent event in IT mass spectrometers. Such ions are the dominant peak in more than 50% of all assigned spectra and one of the five most abundant ions in nearly 80% of the spectra. We also observed that the detection and intensity of the NL was charge state dependent, being more common at lower charges.

Remarkably, there were an equal number of unassigned spectra containing a highly intense NL peak (data not shown). We hypothesize that these spectra showing a classic NL signature could be properly assigned to phosphorylated peptides using better fragmentation schemes. Fragmentation mechanisms alternative to CID have been recently proposed, such as electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) [18], which has been shown to produce backbone fragmentation without phosphate-associated NL [9] and is starting to find its place in large-scale phosphorylation analysis.

3.2 NL-driven data-dependent MS3 and pseudo MS3

To evaluate the performance of MS2 and MS3 strategies for phosphopeptide analysis, three data-dependent acquisition MS methods were implemented. For this comparison, an IMAC enriched complex sample (SCX fraction 5 from the experiment in Fig. 1A) containing hundreds of phosphor-peptides was analyzed in triplicate using the following approaches.

First, we utilized a standard TOP10 method [15] with only MS2 CID fragmentation (TOP10 MS2, Fig. 1B and Fig. 2C). For each cycle, a full MS scan collected with high resolution in the Orbitrap was followed by ten MS2 scans in the linear ITon the ten most intense ions observed in the full MS spectrum. Cycle time was 4.25 ± 0.23 s when all ten MS2-dependent scans were collected.

Second, DDNLMS3 (Fig. 1C and Fig. 2C), where we collected an MS3 spectrum following an MS2 spectrum if two conditions were met: (i) the MS2 revealed a peak at −49, −32.7 or −24.5 mass units from the precursor, corresponding to a loss of phosphoric acid; and (ii) that peak was within the two most intense fragment ions in the MS2 spectrum. When ten MS2 scans were collected, on average three MS3 scans were triggered and cycle times were 5.41 ± 0.30 s. Figures 1E and F show examples of MS2 and MS3 spectra for one of the phosphopeptides identified in this study. The MS2 shows a prominent NL peak.

Third, a multistage activation (or pseudo MS3) method (Fig. 1D and Fig. 2C) was set up following the TOP10 method scheme. For each data-dependent scan, the collisional activation of the precursor was followed by additional activation steps of the product ions at 1 Da mass windows located at −49, −32.7 and −24.5 (NL) from the precursor ion. Since all fragments thus produced were stored and recorded into a single scan, in practice this spectrum is considered a composite of MS2 and MS3 spectra. See Fig. 1G for an example. Average cycle time for this scheme was 5.37 ± 0.25 s.

The mean number of data-dependent MSn scans collected per run using each of these methods is plotted in Fig. 2A. Roughly the same number of MSn scans was collected for the TOP10 MS2 (7303 ± 53) and the DDNLMS3 (5757 ± 23 MS2 and 1722 ± 25 MS3) methods. Extra time spent in additional fragmentations for the pseudo MS3 method provided fewer MSn scans (5859 ± 73).

While a pseudo MS3 scan is faster than an MS2 scan followed by an MS3 scan (see details in Fig. 2C) used in the DDNLMS3 method, a priori knowledge of the presence or absence of neutral loss for the DDNLMS3 method allows triggering of MS3 scans only where a phosphopeptide with relatively intense NL fragment occurred. Consequently, the average cycle times for both methods were comparable (Fig. 2C). Therefore, both MS3 methods were able to perform similar number of scan cycles (822 ± 12 for DDNLMS3 and 831 ± 4 for the pseudo MS3) (Fig. 2B). In this regard, the TOP10 method was 20% faster than the others, exploring a higher diversity of peptide precursor ions (986 ± 16 cycles) (Fig. 2B).

3.3 MS2 and MS3 spectral quality for phosphopeptides

Since MS3 scans are triggered on the precursor neutral loss product ion, the fragmentation pattern is thought to be devoid of such intense ions and hence more similar to that of unmodified peptide ions, at least for singly phosphorylated peptides. Therefore, it might be expected that MS3 spectra will show backbone fragmentation ions of higher intensities than respective MS2 spectra. To test this hypothesis, we selected those MS2–MS3 pairs from all three DDNLMS3 runs where the same sequence was matched after database searching and passed a mass accuracy filter (n = 2439). The percentage of total peptide backbone b- and y-type fragment ions that were matched in the MS2 and the MS3 were compared for each pair and plotted in Fig. 3A. Surprisingly, MS2 spectra produced more sequence informative ions than their MS3 counterparts did (mean MS2 = 0.42, mean MS3 = 0.38, p = 3 × 10−28 paired t-test). However, in some cases, MS2 spectra matching few fragment ions were complemented with a richer MS3 spectrum.

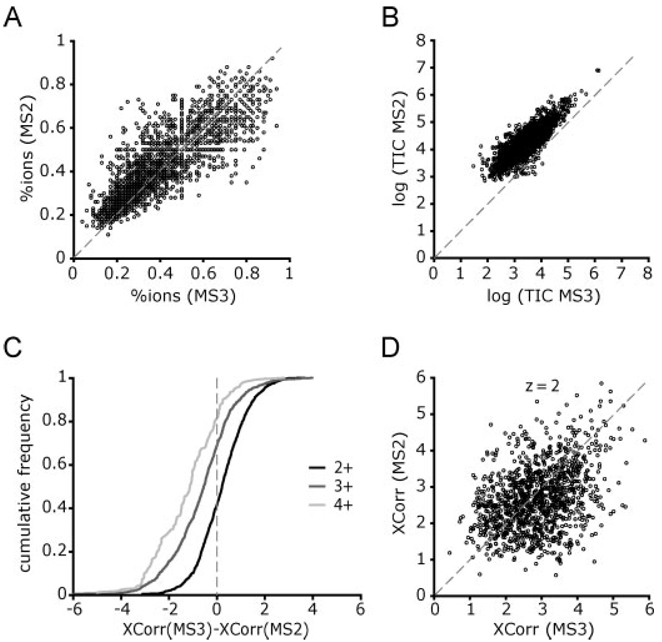

Figure 3.

Comparison of MS2 and MS3 spectra. (A) The percentage of all the sequence b- and y-type ions that were matched in the spectra is plotted for those MS2–MS3 pairs that produced the same peptide sequence (n = 2439). The mean fraction of total ions matched was 0.42 for MS2 spectra and 0.38 for MS3 spectra (P = 3 · 10−28, paired T-test). (B) TIC for all the MS2–MS3 pairs (n = 5117) plotted on a log10 scale. The data points can be fitted to a line with a slope of 1 and an offset 0.8, meaning that only 15% of the total signal from the MS2 spectra is channeled into the MS3 spectra. (C–D) Comparison of XCorr scores between MS2 and MS3 spectra pairs assigned to the same sequence. (C) Cumulative frequency of the difference of XCorr values [XCorr(MS3)-XCorr(MS2)], grouped by charge (z). Xcorr values were clearly superior for MS2 spectra of peptide ions with charge states of 3+ and 4+ and similar for 2+. (D) Scatter plot of XCorr values for peptide ions with charge 2+ (n = 1171). Most of these peptides (94%) were singly phosphorylated.

We observed that most of the MS2 spectra collected maximized the ion injection times before reaching the imposed AGC target of 5000 counts. Thus, because an MS3 spectrum is acquired from isolation and fragmentation of the precursor neutral loss product ion, we expected to obtain MS3 spectra with lower signal than their preceding MS2. In Fig. 3B we observed that in logarithmic scale the TIC for the MS3 correlated linearly with TIC from the MS2, with an intercept at log (MS2 TIC) = 0.8. This means that a given MS3 held only 15% of the intensity of the MS2.

To get a rough estimate of the ion intensity distributed into b- and y-type fragment ions in the MS2, we subtracted the intensity from the neutral loss peak, which on average accounted for 22% of the total intensity of the MS2 spectrum from the TIC of the MS2. The resulting intensity count was still 5 times that from the MS3 spectrum. In summary, MS2 spectra were more intense and contained more sequence informative ions than MS3, regardless of the presence of a highly intense NL peak.

3.4 Do MS3 scans increase confidence in phosphopeptide identifications?

To estimate the FDR in peptide identifications we used the target-decoy database approach [16]. In the DDNLMS3 runs MS2 and MS3 spectra were searched and filtered separately, and the information obtained from both subsets was later combined. The pairing of MS2–MS3 spectra allowed for an additional filtering criterion, requiring that the two spectra match the same peptide sequence. By using this criterion alone in all the MS2–MS3 pairs from the three replicates (n = 5117) we obtained a phosphopeptide dataset at FDR <1% (9 decoy hits in 2480 total pairs). When this was combined with a mass accuracy filter from −4 to +2 ppm, we reached near-certainty of correct identification (0 decoy hits in 2439 total pairs). To determine if the Xcorr values were higher for the MS2 or the MS3 spectra we plotted the difference of Xcorr values [Xcorr (MS3)-Xcorr (MS2)] as a cumulative distribution by charge state (z) (Fig. 3C). MS2 spectra showed higher Xcorr values for most of the 3+ and 4+ peptides, whereas similar quality was observed for 2+ peptides. Further investigations of the data showed poor correlation between Xcorr values in MS2/MS3 pairs, suggesting unpredictability in fragment ion behavior in MS3 spectra (see Fig. 3D where this effect is shown for all 2+ peptides).

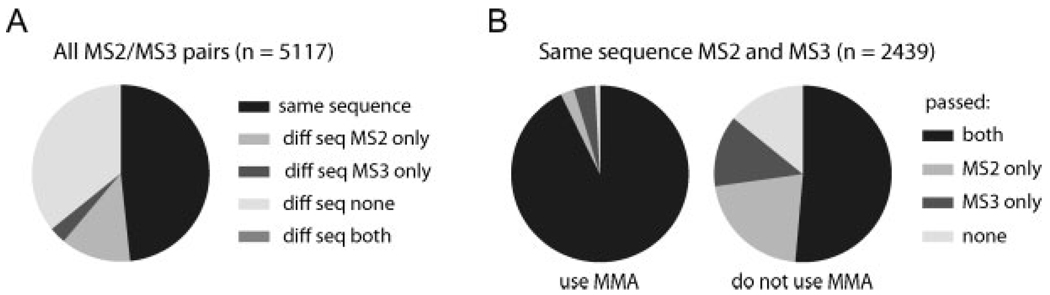

While sequence matching is an excellent criterion that allowed low scoring hits to pass, one might ask how these same MS2 spectra could be identified without MS3 information. We first examined all MS2–MS3 pairs (n = 5117) (Fig. 4A). Thresholds for Xcorr and dCn’ scores according to a <1% FDR were applied to the 2637 MS2 and 2637 MS3 for which different peptide sequence was assigned. Of those, 651 (13%) MS2 passed the filters whereas only 150 (3%) were exclusively identified by MS3. A big portion of the data (1832 pairs, 36%) showing a prominent neutral loss peak, could not be matched successfully to phosphopeptide sequences by neither MS2 nor MS3 scans. We further studied the samesequence pairs (n = 2439) for their ability to pass a 1% FDR threshold (Fig. 4B). We examined this outcome under two conditions: (i) using the accurate masses provided by the Orbitrap mass analyzer, and (ii) simulating low-mass accuracy data (such as that acquired on a stand-alone LTQ) by performing searches at 2 Da and not using accurate masses for filtering. When mass accuracy was used, most peptides passed the filtering criteria for either scan (99%) and the contribution of MS3 scans alone was remarkably small (4%), suggesting that MS3 spectra did not substantially increase the ability to identify a given phosphopeptide. However, in the absence of high-mass accuracy information higher values for SEQUEST XCorr and dCn’ thresholds were required. As a result, many MS2 and MS3 spectra alone did not pass thresholds (14%) but were nonetheless correct, and the contribution of MS3 alone was substantially higher (13%). Both of these groups could be rescued simply by requiring a match of MS2 and MS3 sequences. Overall, we found the contributions of MS3 spectra highly dependent on the presence of mass accuracy information for data filtering. Accurate masses at the levels provided by hybrid instruments such as the LTQFT or the LTQOrbitrap would be sufficient criteria for passing 95% of phosphopeptides matched by MS2 spectra with minimum XCorr and dCn’ thresholds with no need for collecting MS3.

Figure 4.

Peptide spectral matches of MS3 and their preceding MS2 scans for a triplicate analysis a complex phosphopeptide mixture. All three runs used the DDNLMS3 method. As both spectra in each pairwere answers to the same precursor ion species, theywere treated as a unit. (A) All MS2–MS3 pairs (n = 5117) were considered. The first filtering criterion was both spectra (MS2 and MS3) yielding the same peptide sequence (n = 2480, 48%). In this pool only 9 decoy hits were identified, thus the FDR was <1%. The remaining pairs were classified based on passing filtering criteria to establish a 1% FDR only considering MS2 spectra (n = 651, 13%), only MS3 spectra (n = 150, 3%), passing neither (n = 1832, 36%) or passing both with different sequences (at least one is a false positive, n = 4, 0.1%). (B) Only MS2–MS3 pairs that identified the same sequence and passed the mass accuracy filterwere considered (n = 2439, no reverse hits). This dataset should be entirely composed of correct sequence matches. To these spectra, we applied the Xcorr and dCn’ score values according to <1% FDR combined with a mass accuracy filter (“MMA”) or not (“no MMA”). Not using mass accuracy information simulates low mass accuracy phosphopeptide identification. See Section 2 for scoring and mass accuracy filtering criteria. Peptides were classified into four categories: both MS2 and MS3 passing the filtering criteria, only MS2, only MS3 and none passing. Although obtaining the same sequence for both spectra is an excellent filter by itself, in the presence of mass accuracy information, 95% of these MS2 spectra still passed filtering criteria for a 1% FDR.

3.5 Do MS3 scans increase the number of phosphopeptide identifications?

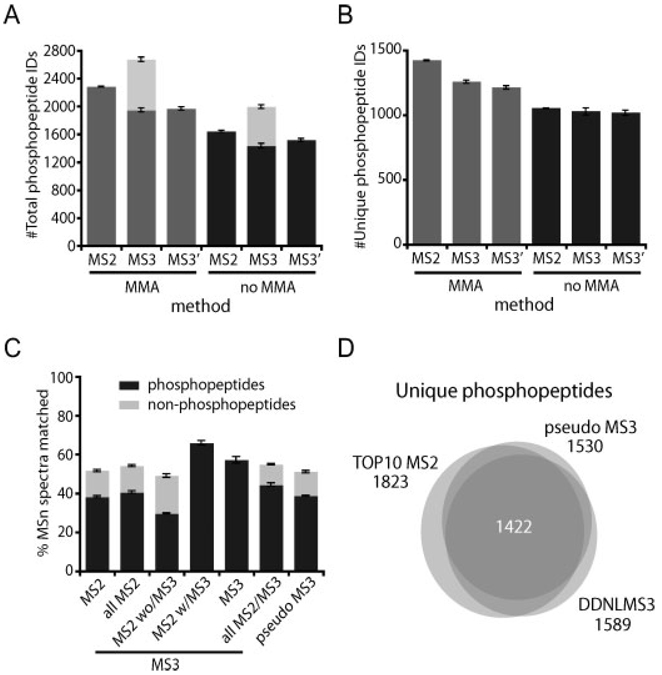

One critical issue in large-scale phosphoproteomics is the number of phosphopeptides (and the FDR) comprised in the final dataset. We evaluated the consequences of collecting potentially more informative spectra at the expense of a longer scan cycle in shotgun phosphopeptide sequencing in the presence and absence of accurate precursor masses as a filtering criteria. The number of total and non-redundant (unique) phosphopeptides obtained is represented in Fig. 5 for each of the three methods. The total number of phosphopeptides identified was greater for the DDNLMS3 method due to redundant sequencing in both MS2 and MS3 spectra for many matches, as reflected in the reduced number of unique hits. However, by extending the scan cycle time using either the DDNLMS3 or pseudoMS3 methods, fewer non-redundant phosphopeptides were confidently identified. This 15% reduction was likely due to reduced time for exploration of lower abundance phosphopeptide ions. This fact is further reflected in the degree of overlapped phosphopeptide sequence identifications between any two duplicates (71%) or the triplicates (59%) from TOP10 MS2 method, which were lower than for the DDNLMS3 method (75% for any two duplicates, 65% for triplicates) and the pseudo MS3 method (73% for any two duplicates, 62% for triplicates).

Figure 5.

Phosphopeptide identifications per analysis at <1% FDR using each of the three methods. Mean ± SD values for triplicate analyses are shown. (MS2 = TOP10 MS2 method, MS3 = DDNLMS3 method, MS3′ = pseudo MS3 method, MMA: searches at 50 ppm precursor mass tolerance, using mass accuracy information as a filtering criteria, no MMA: searches at 2.0 Da precursor mass tolerance, not using mass tolerance as a filter). (A) Total (redundant) phosphopeptide spectral matches. (B) Unique (non-redundant) phosphopeptide sequences. In order to be conservative, unique phosphopeptides were calculated at sequence level without considering different phosphorylation site localizations. (C) Success rate in phosphopeptide and unmodified peptide identification for each method. Values are calculated based on the total number of MSn scans collected. Details for different scan types are given in the MS3 method. (D) Overlap in phosphopeptide identification between the three methods. For simplicity, overlaps were calculated at sequence level without considering different phosphorylation site localizations. Each circle represents the combined triplicate analyses for each of the methods. A total of 2041 non-redundant phosphopeptides were identified in the SCX fraction #5 used in this study.

In the absence of high-mass accuracy information, higher Xcorr and dCn’ thresholds were required for the same precision (1% FDR in this study) and thus, higher quality data had substantial contribution. As seen in Fig. 4B, MS3 contributed with 13% of the identifications obtained between the MS2–MS3 pairs, balancing some of the phosphopeptides missed by the slower scan cycle. Nonetheless, in this scenario, neither DDNLMS3 nor pseudo MS3 were better than the standard TOP10 method.

To provide an idea about the performance of our methods in data acquisition, the success rate in matching MSn spectra is shown in Fig. 5C. More than 50% of any type of data-dependent spectra collected successfully identified a peptide at 1% FDR. The total number of non-redundant phosphopeptide sequences obtained for this single sample was 2041, and the overlap between the three methods for the combined triplicate analyses is shown in Fig. 5D.

3.6 Does MS3 collection help in phosphorylation site localization?

Determining site localization is another important challenge in phosphorylation analysis. The presence of multiple serine, threonine and tyrosine residues in a peptide sequence offers a collection of choices for phosphate assignment. The success of this endeavor depends upon the non-random detection of site-determining ions that differentiate all possibilities. We used the Ascore algorithm, which computes the likelihood that site determining ion differences between the two best candidate positions occurred by chance [17]. An Ascore value is calculated for each site in every peptide.

Site determination for multiply phosphorylated peptides is further complicated with MS3 spectra. This is because the MS3 scans can contain a composite of NL events from multiple sites. Therefore, an MS3 spectrum potentially includes site-determining ions for both the −18-Da and the +80-Da versions for each site, which introduces additional ambiguity. To simplify the comparison for this study, we focused our Ascore analysis on those spectra that (i) matched the same sequence for the MS2 and the MS3 and (ii) were singly phosphorylated (n = 1682).

A scatter plot of Ascore values for individual MS2–MS3 pairs showed that MS3 Ascore values >19 rarely resulted from MS2 spectra with Ascore values <19 (9%; Fig. 6A, green region). Figure 6B shows the Ascore distribution for MS2 and MS3 spectra when the best Ascore values are chosen for each peptide. The cumulative distribution for the best Ascore MS2 and MS3 spectra is shown in Fig. 6C. At any Ascore threshold imposed (measuring precision in localization), more peptides were deemed localized based on the MS2 spectra than on the MS3. At an Ascore value of 19 (p <0.01), MS3 spectra alone resulted in only a 4% increase in localized sites. Indeed, no significant increase in the overall numbers of localized phosphopeptides was found.

4 Concluding remarks

Fragmentation of phosphopeptides by CID is dominated by a signature NL peak with consequent reduction of intensity of sequence informative ions. This deficiency in backbone fragmentation can be linked to reduced performance or even failure of database searching algorithms in sequence matching by minimizing the separation between right and wrong answers. This is particularly true with 3-D traps. New instrumentation features increased ion capacity (2-D traps) to produce richer spectra (MS, MS2 or MS3), and additional mass analyzers (ICR cell or Orbitrap) enabling high-mass accuracy measurements. Both qualities immensely affect the confidence in matching phosphopeptide sequences from MS2 spectra, diminishing the importance of collecting MS3.

In large-scale experiments, data-collection speed determines the degree of exploration of complex samples. We found that the time invested in getting more informative spectra for a particular peptide with approaches such as MS3, reduced opportunities for sequencing new species. Consequently, the total number of non-redundant phosphopeptides populating our final dataset was reduced by 15%. Finally, the contribution of MS3 spectra in site localization (4%) is too minor to justify their use with complex mixtures. Therefore, while MS3 and pseudo MS3 might be of value when using low-mass resolution instrumentation or in single protein analyses their utility for large-scale explorations of the phosphoproteome using hybrid instruments is not justified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Corey E. Bakalarski for his support with in-house proteomics platform. We are also grateful to Wilhelm Haas and Julian Mintseris for constructive comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant HG3456 to S.P.G.

Abbreviations

- DDNL

data-dependent neutral loss

- FDR

false-discovery rate

- MS2

MS/MS

- NL

neutral loss(es)

Footnotes

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, et al. Large-scale characterization of HeLa cell nuclear phosphoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12130–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomaino R, Rush J, Gerber SA, Steen H, et al. Phosphopeptide detection by a data-dependent, neutral-loss driven MS3 scan using ion trap mass spectrometry. 50th American Society for Mass Spectrometry Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruhler A, Olsen JV, Mohammed S, Mortensen P, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics applied to the yeast pheromone signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2005;4:310–327. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400219-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulintz PJ, Bodenmiller B, Andrews PC, Aebersold R, Nesvizhskii AI. Investigating MS2/MS3 matching statistics: a model for coupling consecutive stage mass spectrometry data for increased peptide identification confidence. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7:71–87. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700128-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu LR, Zhu Z, Chan KC, Issaq HJ, et al. Improved titanium dioxide enrichment of phosphopeptides from HeLa cells and high confident phosphopeptide identification by cross-validation of MS/MS and MS/MS/MS spectra. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:4150–4162. doi: 10.1021/pr070152u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen JV, Mann M. Improved peptide identification in proteomics by two consecutive stages of mass spectrometric fragmentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:13417–13422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405549101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Schwartz JC, Hunt DF, Coon JJ. A neutral loss activationmethod for improved phosphopeptide sequence analysis by quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:3590–3598. doi: 10.1021/ac0497104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi A, Huttenhower C, Geer LY, Coon JJ, et al. Analysis of phosphorylation sites on proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae by electron transfer dissociation (ETD) mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607084104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz JC, Senko MW, Syka JE. A two-dimensional quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:659–669. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syka JE, Marto JA, Bai DL, Horning S, et al. Novel linear quadrupole ion trap/FT mass spectrometer: performance characterization and use in the comparative analysis of histone H3 post-translational modifications. J. Proteome Res. 2004;3:621–626. doi: 10.1021/pr0499794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makarov A, Denisov E, Kholomeev A, Balschun W, et al. Performance evaluation of a hybrid linear ion trap/orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:2113–2120. doi: 10.1021/ac0518811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakalarski CE, Haas W, Dephoure NE, Gygi SP. The effects of mass accuracy, data acquisition speed, and search algorithm choice on peptide identification rates in phosphoproteomics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007;389:1409–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. Large-scale phosphorylation analysis of mouse liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1488–1493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas W, Faherty BK, Gerber SA, Elias JE, et al. Optimization and use of peptide mass measurement accuracy in shotgun proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:1326–1337. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500339-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP. A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nat. Bio-technol. 2006;24:1285–1292. doi: 10.1038/nbt1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coon JJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Syka JE. Electron transfer dissociation of peptide anions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:880–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]