Abstract

Fumagillin, an irreversible inhibitor of MetAP2, has been shown to potently inhibit growth of malaria parasites in vitro. Here, we demonstrate activity of fumagillin analogs with an improved pharmacokinetic profile against malaria parasites, trypanosomes, and amoebas. A subset of the compounds showed efficacy in a murine malaria model. The observed SAR forms a basis for further optimization of fumagillin based inhibitors against parasitic targets by inhibition of MetAP2.

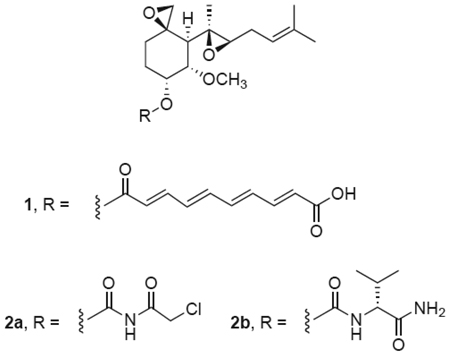

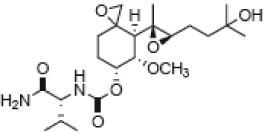

The sesquiterpene fumagillin 1, produced by Aspergillus fumigatus, has been extensively studied for its antimicrobial activity.1 While toxic, it is employed in veterinary applications and to a limited degree in humans, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. A renewed interest in fumagillin, driven by recognition of its anticancer properties, led to identification of its molecular target, methionine aminopeptidase-2 (MetAP2).2 MetAP2 is a cytosolic enzyme which removes methionine from the amino terminus of newly synthesized proteins for subsequent post-translational modifications (e.g. myristoylation), which are required for stability, activity, and intracellular localization.3, 4 A related isoform, MetAP1, can process many of the same substrates, but its relative activity differs from that of MetAP2 based on the nature of the amino acid residues flanking the cleavage site, primarily the residue immediately adjacent to the N-terminal methionine. Fumagillin and structural analogues, such as TNP-470 (AGM-1470), 2a, selectively inhibit MetAP2 enzymatic activity through irreversible, covalent bond formation with histidine-231 in the active site of the enzyme.5, 6

Previously, we showed that fumagillin and TNP-470 inhibited the in vitro growth of Plasmodium falciparum and Leishmania donavani, and speculated that their mode of action might stem from the inhibition of MetAP2.7 Moreover, we reported the cloning of the MetAP2 gene of P. falciparum, the most lethal and common source of malaria infection, and found a 40% sequence homology with the murine and human enzymes. Importantly, fumagillin and TNP-470 showed potent activity against four strains of P. falciparum, including the chloroquine resistant strains W2 and C2B. On average, TNP-470 was approximately 10 times better as an inhibitor (IC50 0.3 – 1.66 ng/mL). These results suggested that the activity of fumagillin could be optimized further. We additionally described the anti-trypanosomal activity of ovalicin, whose structure closely resembles that of fumagillin, and ovalicin analogues.8 Evidence for a direct interaction of PfMetAP2 with fumagillin was also recently reported.9

The concept of MetAP enzymes as anti-infective targets is further validated by the data that a family of structurally related inhibitors containing a 2-(2-pyridinyl)-pyrimidine core was effective therapeutically against malaria in vitro and in mouse models.10 These compounds target specifically PfMetAP1b. In this communication, we disclose new fumagillin analogs that show broad spectrum antiparasitic efficay against malaria parasites, trypanosomes, and amoebae. Moreover, two analogs showed in vivo efficacy against the rodent malaria parasite P. berghei in mice. The results validate fumagillin and its analogues as inhibitors of these parasites, and provide initial SAR for further optimization.

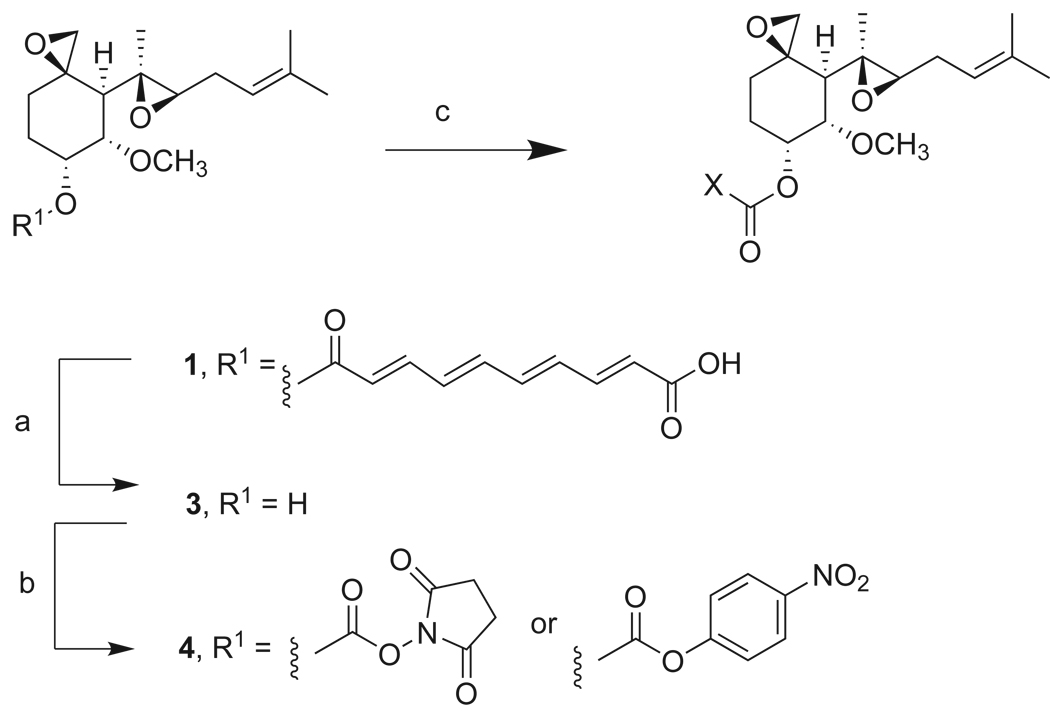

We previously described a strategy to improve the pharmacokinetic and safety profile of fumagillin and TNP-470 by modifying the structure of the substitutent at C6 on the cyclohexane ring, which is a polyolefinic acid in fumagillin and a reactive chloroacetylcarbamate in TNP-470 (Scheme 1).11 Crystallographic studies demonstrated that the primary interactions between fumagillin and MetAP2 involve the reactive spiroepoxide moiety as well as the prenyl containing substituent at C4, whereas the ester chain at C6 extends through a narrow hydrophobic channel to the protein exterior.5 Thus, alterations at C6 should preserve the spiroepoxide scaffold forming the key inhibitory contacts while modulating the physical properties of the molecule and allowing additional interactions with the active site cleft and solvent. We found that incorporation of alkyl carbamate functionalities at this position yielded potent inhibitors of MetAP2 and HUVEC proliferation, resulting in the discovery of PPI-2458 (2b), an orally active fumagillin analog effective in rat models of arthritis.12 The set of compounds chosen for the current study contain basic and acidic groups at a range of distances and orientations from the fumagillin core. Synthesis was accomplished from commercially available fumagillin as described previously.11

Scheme 1.

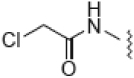

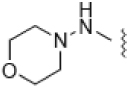

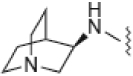

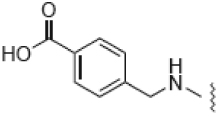

Design and synthesis of fumagillin analogs. Reagents and conditions: (a) NaOH, MeOH, H2O, 0 °C; (b) DSC or 4-NO2 phenylchloroformate, TEA, CH3CN, 25 °C; (c) X, DIEA, CH3CN or EtOH, 25 °C.

For our initial set (Table 1, 5 – 9) we examined whether the activity of TNP-470 could be maintained in nonlabile, compact carbamate derivates containing a range of functional groups. With few exceptions, compounds from this set potently inhibit all three parasite classes at a level similar to that of fumagillin and TNP-470. Hydrazide 5 and carboxylate 7 show the best activity across the panel, indicating that either basic or acidic functionalities are tolerated. Both compounds are also highly efficient inhibitors of hMetAP2, as determined by the level of residual free MetAP2 activity remaining following 8h incubation with compound. In contrast, hydration of the prenyl double bond in 9 causes nearly complete loss of enzyme inhibition, and little to no antiparasitic activity is observed.

Table 1.

Effect of MetAP2 inhibitors on in vitro growth of Entamoeba histolytica, Plasmodium falciparum, and Trypanosoma brucei: initial compound set

| Growth IC50b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structurea | E. histolytica (ng/mL) |

P. falciparum (ng/mL) |

T. brucei (mg/mL) |

% free MetAP2c |

| 1 |  |

5.0 | 99.6 | 26 | ND |

| 2 |  |

26.0 | 12.3 | 2.8 | ND |

| 5 |  |

10.0 ± 0.1 | 7.74 | 28 | 6 |

| 6 |  |

1260 ± 290 | 39.4 | 24 | ND |

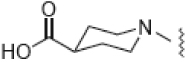

| 7 |  |

10.0 ± 0.1 | 20.5 | 42 | 3 |

| 8 |  |

87.0 ± 0.7 | 36.7 | BLQ | 8 |

| 9 |  |

BLQ | BLQ | BLQ | 90 |

Substituents correspond to X in Scheme 1.

Standard errors are <0.01 unless otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: BLQ, below limit of quantitation; ND, not determined.

MetAP2 inhibition was measured using biotinylated fumagillin to quantitate unreacted enzyme in an ELISA format following 8 h treatment with compound (Supplementary information, Reference 11).

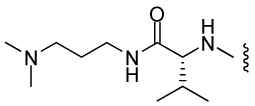

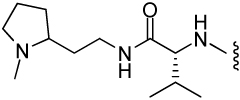

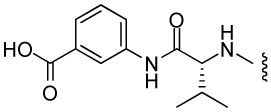

A follow-up set of compounds (Table 2) extended the carbamate moiety with conformationally constrained amino acyl residues as spacers. The effect of this extension is marginal on T. brucei and P. falciparum (D2 strain), but resulted in a 10 – 100 fold loss of activity against E. histolytica. However, little correlation with MetAP2 activity is seen. It is possible that the insertion of the spacer residue lowers the permeability of the compounds in amoeba. Finally, compounds 5 – 14 were also tested against Leishmania donovani, but with the exception of 7, showed no activity at concentrations < 100 µg/mL.

Table 2.

Effect of MetAP2 inhibitors on in vitro growth of Entamoeba histolytica, Plasmodium falciparum, and Trypanosoma brucei: follow-up compound set

| Growth IC50b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structurea |

E. histolytica (ng/mL) |

P. falciparum (ng/mL) |

T. brucei (µg/mL) |

% free MetAP2c |

| 10 |  |

2540 ± 340 | BLQ | BLQ | ND |

| 11 |  |

64.3 ± 0.3 | 28.8 | 55 | ND |

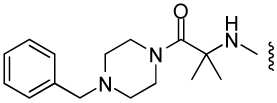

| 12 |  |

2280 ± 310 | 26.3 | 25 | ND |

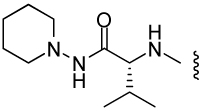

| 13 |  |

1390 ± 420 | 34.7 | 19 | 5 |

| 14 |  |

497 ± 30 | 136 | 14 | 4 |

Substituents correspond to X in Scheme 1.

Standard errors are <0.01 unless otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: BLQ, below limit of quantitation; ND, not determined.

MetAP2 inhibition was measured using biotinylated fumagillin to quantitate unreacted enzyme in an ELISA format following 8 h treatment with compound (Supplementary information, Reference 11).

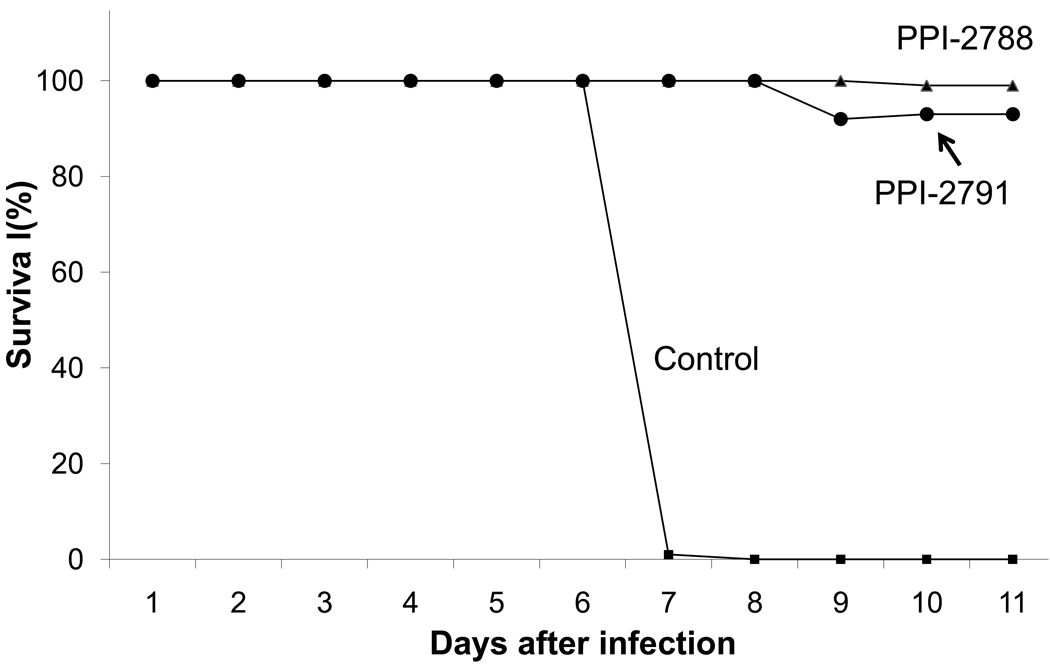

Compounds 12 and 13 (PPI-2788 and PPI-2791) were additionally tested in mice infected with malaria P. berghei (Figure 1). Controls treated with PBS did not survive beyond 7 days post infection, whereas both 12 and 13 were highly protective to 12 days. These results show that significant in vivo efficacy can be achieved with these prototype compounds.

Figure 1.

Effect of MetAP2 inhibitors 12 and 13 on survival of mice infected with malaria P. berghei. Following infection on Day 1, mice were dosed subcutaneously with 25 mg/kg compound every 12 hours, or with PBS as a control. Each data point was the mean of triplicates.

This work builds on earlier studies demonstrating the efficacy of fumagillin and ovalicin analogues against the parasites responsible for chloroquine resistant malaria and sleeping sickness. Based on the homology of human and Plasmodium MetAP2, we hypothesized that fumagillin analogues would potently inhibit parasitic MetAP2’s and demonstrate efficacy in vivo resulting from blockage of an essential housekeeping enzyme. Separately, we showed that the toxicity and poor pharmacokinetics of TNP-470, the most potent inhibitor described for MetAP2, could be remedied by replacement of the chloroacetamido side chain with a carbamate functionality.11, 12 This work also demonstrated a cytostatic, rather than cytotoxic, antiproliferative effect for this inhibitor class against sensitive cell types.12 Following this strategy, the carbamates tested here combine favorable PK properties, including oral bioavailability, with high potency against a panel of parasites, thus laying a basis for further optimization.11 It is evident that the side chains of both fumagillin and TNP-470 can be replaced by groups which are compact and nonlabile. The complete lack of activity shown by a closely related compound, 9, where the essential MetAP2 binding region is modified further supports the conclusion that the efficacy of this compound class in vivo is linked to inhibition of this enzyme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Karl Werbowetz of the Division of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy, Ohio State University School of Pharmacy, for testing these compounds against L. donovani. This work was supported in part by The Sandler Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article (synthetic methods for compounds 5–14 and assay procedures) can be found in the online version.

References

- 1.Lefkove B, Govindarajan B, Arbiser JL. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2007;5:573. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ingber D, Fujita T, Kishimoto S, Sudo K, Kanamuru T, Brem H, Folkman J. Nature. 1990;348:555. doi: 10.1038/348555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sin N, Meng L, Wang MQW, Wen JJ, Bornmann WG, Crews CM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Griffith EC, Su Z, Turk BE, Chen S, Chang Y-H, Wu W, Biemann K, Liu JO. Chemistry and Biology. 1997;4:461. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang Y-H, Teichert U, Smith JA. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:8007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Li X, Chang Y-H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:12357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li X, Chang Y-H. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;227:152. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Widom J, Kemp CW, Crews C, Clardy JW. Science. 1998;282:1324. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffith EC, Su Z, Niwayama S, Ramsay CA, Chang Y-H, Liu JO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P, Nicholson DE, Bujnicki JM, Su X, Brendle JJ, Ferdig M, Kyle DE, Milhous WK, Chiang PK. J. Biomed. Sci. 2002;9:34. doi: 10.1007/BF02256576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hua DH, Zhao H, Battina SK, Lou K, Jimenez AL, Desper J, Perchellet EM, Perchellet J-PH, Chiang PK. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:5232. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Xie S, Bhat S, Kumar N, Shapiro TA, Liu JO. Chemistry and Biology. 2009;16:193. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Chen X, Chong CR, Shi L, Yoshimoto T, Sullivan DJ, Jr, Liu JO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604101103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Musonda CC, Whitlock GA, Witty MJ, Brun R, Kaiser M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:401. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson GL, Self C, Lee L, Cook CM, Birktoft JJ. 6,548,477. U.S. Patent. 2003 Arico-Muendel, C. C. et al in preparation.

- 12.Bernier SG, Lazarus DD, Clark E, Doyle B, Labenski MT, Thompson CD, Westlin WF, Hannig G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404105101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.