Abstract

Mutations in PINK1 and parkin cause autosomal recessive parkinsonism, a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons. To highlight potential therapeutic pathways we have identified factors that genetically interact with parkin/PINK1. Here we report that overexpression of the translation inhibitor 4E-BP can suppress all pathologic phenotypes including degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. 4E-BP is activated in vivo by the TOR inhibitor rapamycin, which we find can potently suppress pathology in PINK1/parkin mutants. Rapamycin also ameliorates mitochondrial defects in cells from parkin-mutant patients. Recently, 4E-BP was shown to be inhibited by the most common cause of parkinsonism, dominant mutations in LRRK2. Here we further show that loss of the Drosophila LRRK2 homolog activates 4E-BP and is also able to suppress PINK1/parkin pathology. Thus, in conjunction with recent findings our results suggest that pharmacologic stimulation of 4E-BP activity may represent a viable therapeutic approach for multiple forms of parkinsonism.

Keywords: parkinsonism, neurodegeneration, parkin, PINK1, 4E-BP, rapamycin, TOR, LRRK2

Parkinson disease (PD) is the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder, affecting ~1% of the elderly population. There are currently no cure and no effective disease-modifying therapies. The pathology of PD is principally characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra which causes progressive loss of motor functions and other symptoms. The precise pathologic mechanisms remain unclear, however, the identification of several genes associated with rare, heritable forms of PD have highlighted putative pathogenic causes such as mitochondrial dysfunction and aberrant protein degradation1, 2. In addition, oxidative stress is a prominent and common feature in all forms of PD and likely represents a convergent toxic event leading to neuronal cell death.

Disruption of two genes, parkin, which encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and PINK1, encoding a mitochondrially targeted kinase, result in autosomal recessive parkinsonism2. Recent analyses have revealed that PINK1 and Parkin act in a common pathway that maintains mitochondrial integrity3-6. Genetic studies of the Drosophila PINK1 and parkin mutants, which exhibit dopaminergic neurodegeneration, locomotor deficits and mitochondrial dysfunction, have been instrumental in understanding the pathogenesis and highlighting potential protective pathways7. Additional components of the PINK1/Parkin pathway8, 9 and its function in affecting mitochondrial dynamics6, 10-12 are being elucidated, however, it is currently unclear how these pathologic effects may be circumvented to prevent neurodegeneration. To address this we previously conducted a genetic screen for modifiers of Drosophila parkin mutants to identify factors that enhance or suppress parkin pathology. This approach has the potential to identify factors acting directly on the PINK1/Parkin pathway or indirectly, highlighting parallel pathways that mediate cell-protective mechanisms. In this screen we identified the Drosophila gene Thor, which encodes the sole ortholog of mammalian 4E-BP113. 4E-BP1 is an inhibitor of translation that has previously been implicated in mediating the survival response to various physiological stresses14-16.

The ability of a cell to elicit a rapid response to intrinsic or extrinsic stress is essential for survival. Regulated control of translation is an elaborate mechanism that allows immediate changes in gene expression from existing mRNAs. Initiation of translation is the rate-limiting step, and thus subject to precise regulation. Translation initiation is governed by the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), which mediates the binding of the eIF4F complex to the mRNA 5′ cap structure16, 17. The availability of eIF4E is regulated by eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), which bind and sequester eIF4E, preventing eIF4F complex formation and translation. In turn, the activity of 4E-BPs is tightly regulated by phosphorylation. Hypo-phosphorylated 4E-BP1 binds eIF4E with high affinity, however, upon hyper-phosphorylation 4E-BP1 dissociates from eIF4E allowing 5′ cap-dependent translation to occur. Central to the regulation of 4E-BP phosphorylation is the conserved TOR signaling pathway. TOR is activated in response to numerous stimuli including activation of the PI3K/Akt1 pathway, whereupon it phosphorylates 4E-BP and other factors promoting translation. Thus, TOR signaling coordinates cell growth and metabolism in response to physiological changes18, 19.

Inhibition of cap-dependent translation by 4E-BP is essential for survival under stress conditions. 4E-BP has been shown to be important for survival under a wide variety of stresses including starvation, oxidative stress, unfolded protein stress and immune challenge20-24. Many cellular stressors result in the rapid cessation of cap-dependent translation, which is accompanied by the concomitant promotion of cap-independent translation of essential pro-survival factors14, 25. Switching the translational profile from cap-dependent to cap-independent provides the cell with ability to rapidly respond to environmental changes and transient stresses.

Here we show in Drosophila that loss of 4E-BP function dramatically reduces parkin and PINK1 mutant viability. In contrast, overexpression of 4E-BP is sufficient to suppress all pathologic phenotypes in these mutants, including neurodegeneration. We also show that activation of 4E-BP by pharmacologic inhibition of its negative regulator TOR with rapamycin is able to elicit a similar protective effect in vivo. Importantly, rapamycin treatment is also able to ameliorate mitochondrial defects in parkin-mutant PD patient cell lines. Furthermore, we provide the first evidence that the Drosophila homolog of LRRK2 genetically interacts with PINK1/parkin mutants, consistent with a recent report showing LRRK2 regulates the activity of 4E-BP26. Thus, our results suggest that modulating 4E-BP activity represents a viable therapeutic target to modify the pathologic process and may be applicable to multiple forms of parkinsonism.

RESULTS

4E-BP genetically interacts with the Parkin/PINK1 pathway

In a screen for parkin modifiers we previously recovered a P-element neighboring the Drosophila gene Thor, which encodes the sole ortholog of mammalian 4E-BP113. [Here we refer to the endogenous gene as Thor, as per established FlyBase nomenclature, and transgenes or the protein as 4E-BP.] To confirm and extend the analysis of this genetic interaction we obtained an independent, previously characterized null allele Thor2 to cross with null mutations in parkin (park25) and PINK1 (PINK1B9).

In contrast to parkin and PINK1 mutants, homozygous Thor2 mutants are fully viable and fertile, and show no overt phenotypes under normal conditions20. Surprisingly, we found Thor2:park25 double mutants were essentially lethal (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Rare escapers were occasionally recovered but died shortly after eclosing as adults. This synthetic lethality could be rescued by targeted expression of a 4E-BP wild type transgene.(Supplementary Fig. S1b). Similarly, we found Thor2:PINK1B9 double mutants showed a significant reduction in viability (Fig. S1c), although the degree of interaction was not as severe. Heterozygous combinations of Thor2 and park25 or PINK1-B9 mutations had no significant effect on viability.

4E-BP overexpression suppresses parkin/PINK1 phenotypes

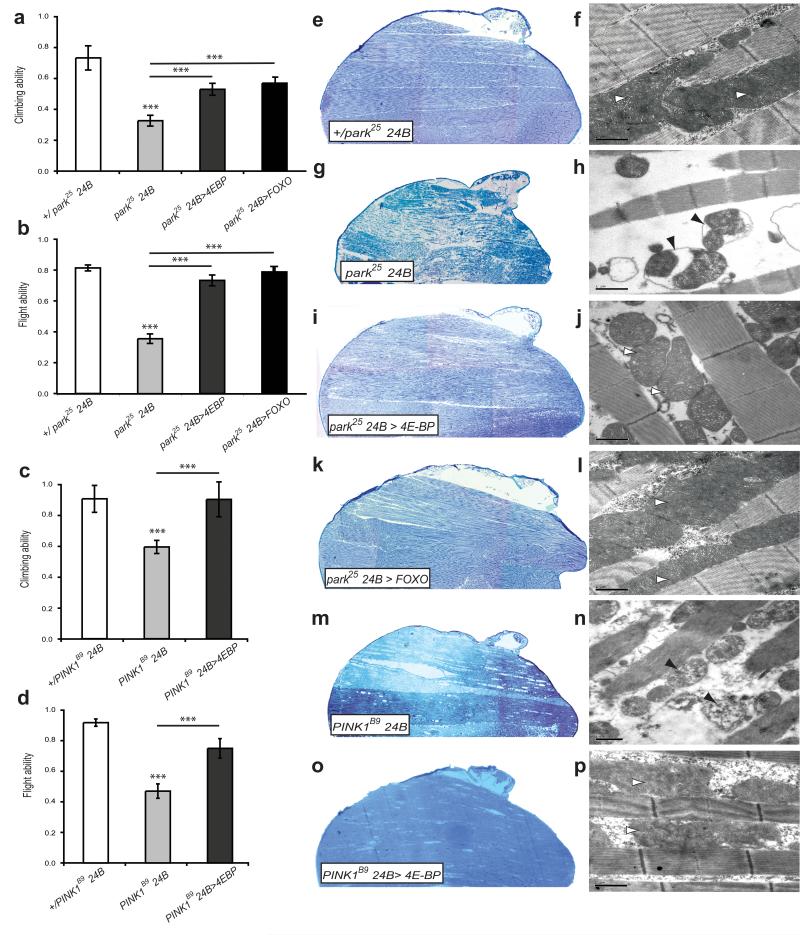

Since loss of 4E-BP is detrimental to parkin and PINK1 mutants, we reasoned that increased 4E-BP expression may confer a protective effect. PINK1 and parkin mutants exhibit locomotor deficits in flight and climbing ability, widespread muscle degeneration and mitochondrial defects. Overexpression of 4E-BP, using the muscle specific 24B-GAL4 driver, significantly suppressed climbing and flight defects in both parkin and PINK1 mutants (Fig. 1a-d). Muscle degeneration and mitochondrial disruption seen in parkin/PINK1 mutants was also abrogated by 4E-BP overexpression (Fig. 1e-p).

Figure 1. 4E-BP overexpression suppresses parkin/PINK1 locomotor deficits and muscle degeneration.

Overexpression of 4E-BP suppresses climbing and flight defects of (a, b) parkin and (c, d) PINK1 mutants. Overexpression of FOXO also rescued locomotor deficits in parkin mutants (a, b). (e-p) Toluidine blue stained sections of adult thorax and TEM images of muscle show 4E-BP or FOXO overexpression suppresses muscle degeneration and mitochondrial defects. Abnormal mitochondrial morphology in mutants (black arrowheads) is restored (white arrowheads). Scale bars show 1μm. Charts show mean and SEM. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (*** P<0.001).

park25 and PINK1B9 mutants exhibit age-related degeneration of a subset of dopaminergic neurons4, 27. The tyrosine hydroxylase-GAL4 line (THG4) was used to drive expression of 4E-BP in dopaminergic neurons of parkin and PINK1 mutants and the number of dopaminergic neurons surviving in the PPL1 cluster of aged animals was analyzed. Strikingly, we found that overexpression of 4E-BP in PINK1 and parkin mutants was capable of significantly suppressing dopaminergic neuron loss (Fig. 2a) in parkin and PINK1 mutants. Interestingly, consistent with a previous study26 Thor2 mutants also display loss of dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 2b). Together these findings indicate that 4E-BP is required to prevent neurodegeneration and increasing 4E-BP levels is capable of mediating a protective mechanism sufficient to prevent the pathologic consequence of loss of Parkin or PINK1.

Figure 2. Overexpression of 4E-BP can suppress degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in parkin/PINK1 mutants.

Quantification of anti-tyrosine hydroxylase positive stained dopaminergic neurons in the PPL1 cluster. (a) Effect of 4E-BP or FOXO overexpression in parkin or PINK1 mutants. Control genotype: park25/+; THG4/+. (b) Thor2 mutants show loss of dopaminergic neurons after 30 days compared to a revertant control. Charts show mean and SEM, n ≥ 10. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (*** P<0.001, * P<0.05).

4E-BP pathway is activated in parkin/PINK1 mutants

To gain insight into the status of 4E-BP activity in parkin/PINK1 mutants, we examined the transcriptional, translational and post-translational state of 4E-BP. First, we quantified the relative levels of Thor transcript and found that the levels were not significantly different in mutants compared to wild type (Supplementary Fig. S2a). 4E-BP activity is regulated by altered phosphorylation state so we examined the relative levels of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated 4E-BP. Western blot analysis revealed that there was a significant reduction in the level of hyper-phosphorylated 4E-BP in parkin and PINK1 mutants, and a concomitant increase in the proportion of active, non-phosphorylated 4E-BP (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3. Post-translational state of 4E-BP activity in parkin/PINK1 mutants.

(a) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated 4E-BP levels in adult tissue from control, parkin, and PINK1 mutant flies. Thor2 mutant flies were used as a negative control. (b) Relative levels of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated 4E-BP after normalization for total levels of 4E-BP. (c) Western blots for phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated Akt1 in control, parkin and PINK1 mutant adult tissue. (d) Quantified proportion of phospho-Akt1 relative to total Akt1. Charts show mean and SEM of at least three independent experiments. Significance was determined by Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction (***P<0.001, *P<0.05).

Under normal conditions 4E-BP function is actively repressed by the Akt1/TOR signaling pathway, thus, the previous result suggests that this pathway itself may be down-regulated in response to loss of parkin/PINK1 function. To assess the broader effects of parkin/PINK1 mutations on the pathway that regulates 4E-BP we examined the activity status of Akt1, an upstream regulator of 4E-BP which is itself activated by phosphorylation. The relative amount of active, phosphorylated Akt1 is markedly reduced in parkin and PINK1 mutants (Fig. 3c,d), indicating a down-regulation of this pathway.

Akt1 signaling inactivates the transcription factor FOXO which regulates the expression of Thor28, 29. FOXO is also known to regulate the expression of a large number of stress response factors and detoxification enzymes30, 31, and has been shown to influence lifespan and stress resistance across taxa including Drosophila32, 33. Thus, we sought to test whether overexpression of FOXO modulated parkin and PINK1 phenotypes. While widespread overexpression of FOXO is lethal in a wild-type background, we surprisingly recovered viable parkin mutants overexpressing FOXO, however, overexpression in a PINK1 mutant background was lethal. Interestingly, we found that FOXO overexpression significantly rescued the flight and climbing defects (Fig. 1a,b), restored muscle integrity (Fig. 1k,l), and prevented dopaminergic neuron loss in parkin mutants (Fig. 2a) to the same extent as 4E-BP overexpression.

These results indicate that in parkin/PINK1 mutants the Akt1/TOR signaling pathway that regulates 4E-BP activity and global protein translation is down-regulated typical of a stress response to promote protective mechanisms. Our genetic studies indicate that this endogenous mechanism can be ectopically further upregulated, therefore, we next sought to achieve this by pharmacologic inhibition of TOR signaling.

Rapamycin suppresses parkin/PINK1 pathology

4E-BP is negatively regulated via phosphorylation by TOR which can be inhibited by exposure to rapamycin34. Therefore, we reasoned that administering rapamycin to parkin/PINK1 mutants could promote 4E-BP hypo-phosphorylation and confer a protective effect. Mutant and control flies were raised on normal food supplemented with rapamycin or vehicle alone. Consistent with previous reports35, 36, we found rapamycin treatment led to 4E-BP hypo-phosphorylation in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S2b,c).

Treatment with rapamycin significantly reduced the appearance of thoracic indentations, a surrogate marker for flight muscle degeneration, in both parkin and PINK1 mutants (Fig. 4a). In addition, mutant flies fed rapamycin showed suppression of the climbing deficits, muscle degeneration and mitochondrial defects in the mutant flies (Fig. 4b,d-i). Remarkably, we also found that in parkin and PINK1 mutant flies raised and aged on rapamycin supplemented food dopaminergic neurodegeneration was completely suppressed (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Pharmacological suppression of parkin/PINK1 mutant phenotypes by rapamycin.

(a) Thoracic indentations, (b) climbing ability, and (c) number of dopaminergic neurons in parkin and PINK1 mutants fed rapamycin or vehicle (DMSO). (d-f) TEM of muscle sections from control (DMSO) treated wild type, parkin and PINK1 mutants. (g-i) TEM of muscle sections from rapamycin fed wild type, parkin and PINK1 mutants Scale bars show 2μm. Wild types are out-crossed heterozygous mutations. Charts show mean and SEM. Significance determined by Student’s t-test (*** P<0.001, ** P<0.01).

Treatment of Drosophila cells treated with dsRNA against parkin, which causes a dramatic reduction in parkin transcript and protein levels (Supplementary Fig. S3a,b), leads to a significant elongation of the mitochondrial reticulum (Fig. 5a), similar to the recently reported mitochondrial elongation in fibroblasts from PD patients with parkin mutations12. Co-treatment with rapamycin effectively suppressed the mitochondrial morphology defects in parkin-deficient Drosophila cells (Fig. 5a). We wanted to extend these findings to determine whether rapamycin treatment is relevant to human pathology. Strikingly, rapamycin treatment of parkin-deficient fibroblasts was also able to suppress the mitochondrial elongation and partially rescue the loss of membrane potential (Fig. 5b,c).

Figure 5. Rapamycin rescues mitochondrial defects in parkin-deficient Drosophila and human cells.

Analysis of mitochondrial aspect ratio (length) in (a) parkin RNAi treated Drosophila cells, and (b) fibroblasts from individuals with parkin mutations after exposure to rapamycin or vehicle. (c) Mitochondrial membrane potential in human parkin-deficient fibroblasts after rapamycin or control treatment. Charts show mean and SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s comparison for Drosophila cells or two-way ANOVA for fibroblast lines (*** P<0.001, ** P<0.01, * P<0.05).

The effects of rapamycin are mediated by 4E-BP

Inhibition of TOR by rapamycin exerts effects in addition to those on 4E-BP, for example promoting autophagy. Autophagy has received much attention as a putative protective mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases, particularly in the clearance of misfolded or undegraded proteins. Thus, we wished to determine whether the beneficial effects of rapamycin are operating through 4E-BP-dependent or 4E-BP-independent mechanisms, or a combination.

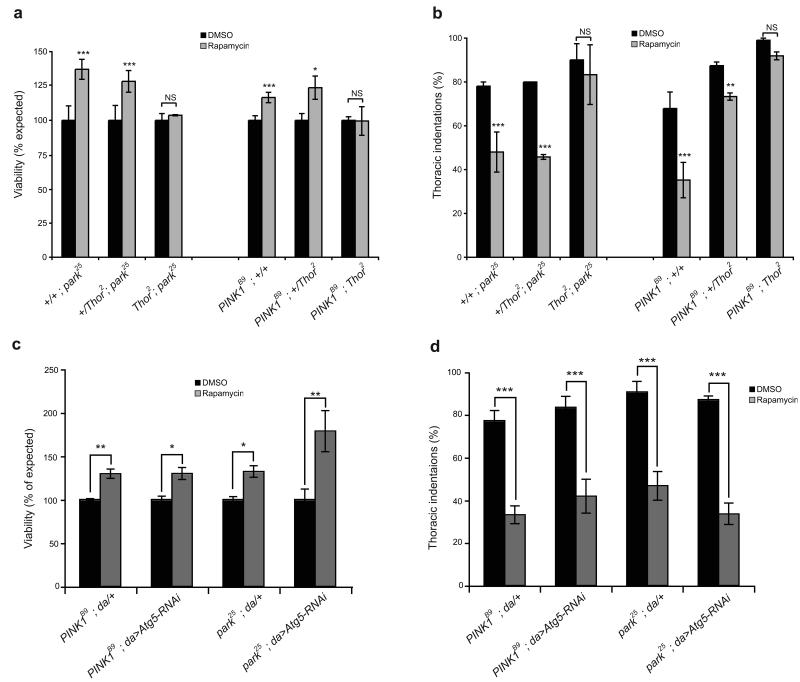

To address this directly, we took a genetic approach to test whether the rapamycin protection required 4E-BP. parkin and PINK1 mutants were placed in combination with Thor2 null mutations and administered rapamycin or vehicle as before. Rapamycin treatment again improved viability and reduced the presence of thoracic indentations in parkin and PINK1 mutants (Fig. 6a,b), however, in a homozygous Thor2 mutant background, suppression of parkin/PINK1 phenotypes was completely abolished (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, attenuating the induction of autophagy by RNAi mediated knock-down of Atg5 (Supplementary Fig. S3c) had no effect on the rapamycin-induced suppression of parkin/PINK1 phenotypes (Fig. 6c,d). These results indicate that the beneficial effects of rapamycin require the activity of 4E-BP and not autophagy. Consistent with this we also found that rapamycin did not prevent degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in Thor2 mutants (Fig. 2b).

Figure 6. Rapamycin suppression of parkin/PINK1 phenotypes is dependent on 4E-BP but does not require autophagy.

Effects of rapamycin on (a,c) viability or (b,d) thoracic indentations in parkin and PINK1 mutants in combination with Thor2 mutations or RNAi-mediated knockdown of Atg5. Charts show mean and SEM of triplicate experiments. Significance determined by Mann-Whitney tests (*** P<0.001, ** P<0.01, * P<0.05).

4E-BP activity upregulates the detoxifying enzyme GstS1

Active 4E-BP induces the rapid cessation of cap-dependent translation to promote the upregulation of stress response factors such as antioxidants and chaperones. The precise changes to the proteomic signature induced upon 4E-BP activation are currently unknown but are likely to be numerous. We previously showed that transgenic overexpression of the antioxidant and detoxifying enzyme GstS1 was sufficient to suppress parkin phenotypes27, therefore, it seemed possible that upregulation of GstS1 may constitute part of the 4E-BP mediated stress response.

Assessing the protein levels of GstS1 we found they were increased upon either transgenic overexpression of 4E-BP or the administration of rapamycin (Fig. 7). Together with our previous findings, this supports a role for the upregulation of stress response factors by activation of 4E-BP. Further work to elucidate the exact translational changes induced by 4E-BP activity will provide important insight into the molecular mechanisms that promote neuro-protection.

Figure 7. GstS1 levels are increased by 4E-BP activation.

(a) Western blot analysis of GstS1 levels in WT (w; 24B-GAL4/+), transgenic 4E-BP overexpression (w; 24B-GAL4/UAS-4E-BP), and wild type flies treated with rapamycin or vehicle. (b) Quantified GstS1 protein levels are normalized to a Tubulin loading control. Charts show mean and SEM of at least three replicates. Statistical analysis was Student’s t-test (**P<0.01, *P<0.05).

Genetic interaction with Drosophila LRRK2 homolog

Dominant pathogenic mutations in LRRK2 are known to cause aberrant increase in its kinase activity37, 38. Recently, it was shown that 4E-BP is a substrate of human LRRK2 and the Drosophila ortholog (LRRK) and that pathogenic mutations cause hyper-phosphorylation of 4E-BP in vivo, leading to reduced oxidative stress resistance and dopaminergic neurodegeneration26. We therefore hypothesized that loss of LRRK2 would lead to hypo-phosphorylated 4E-BP, which should promote a protective response.

In agreement with Imai et al.26, we find that homozygous LRRKe03680 loss-of-function mutations cause a decrease in levels of phosphorylated 4E-BP compared to wild type (Fig. 8a,b), although this does not detectably decrease further in parkin/PINK1 mutant adults. LRRK mutants exhibit normal flight and mildly reduced climbing ability (Fig. 8d,e), however, we found that combining homozygous LRRKe03680 with parkin/PINK1 mutations significantly rescued the dopaminergic neuron loss, flight and climbing deficits of parkin and PINK1 mutants (Fig. 8c-e). These results are consistent with normal LRRK function, in part, negatively regulating survival programs necessary for dopaminergic neuron survival.

Figure 8. Loss of Drosophila LRRK increases the hypo-phosphorylated 4E-BP and partially suppresses parkin and PINK1 mutant phenotypes.

(a) Western blot analysis of levels of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated 4E-BP. (b) Quantification of relative amounts of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated 4E-BP after normalization for total levels of 4E-BP. The mean and SEM of three independent experiments are represented. Analysis of (c) dopaminergic neurons, (d) flight and (e) climbing in mutant combinations. Charts show mean and SEM. Wild type is park25/+; LRRK e03680/+.

Discussion

We have used Drosophila as a model system to uncover genetic suppressors in order to understand the pathogenic mechanisms and to highlight putative therapeutic pathways for PD. We previously identified Thor, the sole Drosophila homolog of mammalian 4E-BP1, as a genetic modifier of parkin. In the present study, we have further characterized the genetic interaction of Thor with parkin and PINK1. While loss-of-function mutations in Thor dramatically decrease parkin and PINK1 mutant viability, overexpression of 4E-BP is able to suppress PINK1 and parkin mutant phenotypes, including degeneration of dopaminergic neurons. These results suggest that 4E-BP acts to mediate or promote a survival response implemented upon loss of parkin or PINK1.

4E-BP1 is an inhibitor of 5′ cap-dependent protein translation, which is known to play an important role in cellular response to changes in environmental conditions such as altered nutrient levels and various physiological stresses14, 25. It has been demonstrated that Drosophila 4E-BP is important for survival under a wide variety of stresses including starvation, oxidative stress, unfolded protein stress and immune challenge20-23. Such a response pathway represents a likely target for possible manipulation by therapeutics. Our genetic evidence supports this idea, hence, we sought to validate whether this represented a viable therapeutic target.

4E-BP activity is regulated post-translationally by the TOR signaling pathway. Activated TOR hyper-phosphorylates 4E-BP inhibiting it leading to promotion of 5′ cap-dependent translation18, 39. Rapamycin is a small molecule inhibitor of TOR signaling and has been shown to lead to 4E-BP hypo-phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo35, 36. Our genetic evidence suggested that administration of rapamycin to parkin/PINK1 mutants should relieve 4E-BP inhibition and confer a protective effect. Exposing mutant animals to rapamycin during development caused an increase in hypo-phosphorylated 4E-BP and, remarkably, was sufficient to suppress all pathologic phenotypes, including muscle degeneration, mitochondrial defects and locomotor ability. Continued administration of rapamycin during aging also completely suppressed progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons..

To validate this pathway as a viable target for therapy we extended our studies to human tissue. There is growing evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction is a key pathologic event across the spectrum of parkinsonism. We and others have reported mitochondrial defects in a number of cell lines derived from patients with parkin mutations12, 40. Here we show that rapamycin is also capable of ameliorating mitochondrial bioenergetic and morphological defects in parkin-deficient PD patient cell lines. Thus, our results provide strong support for the proposition that modulating 4E-BP mediated translation by pharmaceuticals such as rapamycin can be efficacious in vivo and is relevant to human pathophysiology.

TOR signaling regulates a number of downstream effectors other than 4E-BP, for example, up-regulation of S6 kinase promoting protein synthesis and cell proliferation, and down-regulation of autophagy likely through inhibition of ATG119. The coordinated regulation of these pathways serves to optimize cellular activity in response to vital changes such as nutrient availability and environmental stresses. Stimulation of autophagy under nutrient-deprived conditions is a survival mechanism that recycles essential metabolic components, but this mechanism also promotes the degradation of aggregated or misfolded proteins. Thus, the potential therapeutic effects of rapamycin have been widely promoted as a strategy to combat a number of neurodegenerative diseases including PD primarily for its perceived role in promoting autophagic clearance of aggregated proteins. However, recent studies have provided compelling evidence that the pro-survival effects of rapamycin can be mediated in the absence of autophagy by reducing protein translation41, 42. We have demonstrated here that genetic ablation of 4E-BP is sufficient to completely abrogate any beneficial effects of rapamycin in vivo while inhibiting Atg543, a key mediator of autophagy44, does not diminish the efficacy of rapamycin-mediated protection. Together, these results indicate that in this instance the major protective effects of rapamycin treatment are mediated through regulated protein translation, with little or no contribution from autophagy.

A switch from cap-dependent to cap-independent translation is likely to effect widespread changes in the proteome, particularly the induction of pro-survival factors including chaperones, anti-oxidants and detoxifying enzymes. In support of this, we have shown that transgenic or rapamycin-induced 4E-BP activation leads to increased protein levels of GstS1, a major detoxification enzyme in Drosophila45. Interestingly, we previously showed that transgenic overexpression of Drosophila GstS1 is able to suppress dopaminergic neuron loss in parkin mutants27. Elucidating the global changes in response to 4E-BP activation will be crucial to understanding the exact molecular mechanisms of neuro-protection but currently remains unresolved.

The potential importance of 4E-BP modulation as a therapeutic target is underscored by recent findings that report the most common genetic cause of PD, dominant mutations in LRRK2, inhibit 4E-BP function through direct phosphorylation26. Expression of these mutations causes disruption of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila26 and mouse46, however, in striking similarity to our results, overexpression of 4E-BP can circumvent the pathogenic effects of mutant LRRK2 and prevent neurodegeneration26 in Drosophila. Here we show that loss of Drosophila LRRK leads to activation of 4E-BP and can suppress pathology in PINK1 and parkin mutants. These data further support a link between LRRK2 and 4E-BP activity and a common cause of PD. Thus, our results indicate that promoting 4E-BP activity may be beneficial in preventing neurodegeneration in multiple forms of parkinsonism. Since 4E-BP activity can be manipulated by small molecule inhibitors such as rapamycin, this pathway represents a viable therapeutic target. It will be particularly interesting to determine whether rapamycin is efficacious in ameliorating pathologic phenotypes in the recently reported LRRK2 transgenic mouse model46, but further studies will be necessary to determine whether pharmacologic modulation of 4E-BP function is therapeutically relevant in all forms of parkinsonism including sporadic PD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank L Pallanck, P Ingham and L Partridge for critical reading of the manuscript. We would also like to thank Drs Chung, Birman, Partridge, Sonenberg and Neufeld for Drosophila lines, and Dr Benes for the anti-GstS1. This work is supported by grants from the Parkinson’s Disease Society UK (G-4063, G-0713 to A.J.W. and G-0715 to O.B.) and the Royal Society and Wellcome Trust (081987) to A.J.W. We also acknowledge the Department of Biomedical Science, Centre for Electron Microscopy for assistance. The MRC Centre for Developmental and Biomedical Genetics is supported by Grant G070091. The Wellcome Trust (Grant No. GR077544AIA) is acknowledged for support of the Light Microscopy Facility.

Appendix

Methods

Fly stocks and procedures

Drosophila were raised under standard conditions at 25°C on agar, cornmeal, yeast food. park25 mutants have been described before47. pink1B9 mutants4 were provided by J. Chung (KAIST) and the tyrosine hydroxylase-GAL4 (THG4) driver was a gift from S. Birman (Institute of Marseille, France). UAS-FOXO48 was provided by L. Partridge (UCL, London) and UAS-4E-BP49 was obtained from N. Sonenberg (McGill University). UAS-Atg5-RNAi was provided by T. Neufeld43. 24B-GAL4, da-GAL4, PBac{RB}LRRKe03680 and Thor2 strains were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN).

A high proportion of X-chromosome non-disjunction occurs in PINK1 mutant stocks, so crosses to combine PINK1 mutants with GAL4/UAS transgenes used paternal males with y- or FM7-GFP backgrounds to allow correct identification of PINK1 mutant progeny. Flight and climbing assays were performed as previously described47. Rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to standard fly food at 0.5 μm for larval feeding and at 200 μm for adult feeding.

Histology

Tissue sectioning and TEM

Thoraces were prepared from 5-day old adult flies and treated as previously described (Greene et al. 2003). Semi-thin sections were then taken and stained with Toluidine blue, while ultra-thin sections were examined using a TEM (FEI tecnai G2 biotwin 120KV).

Brains were dissected from 30-day old flies and treated for anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (Immunostar Inc.) staining as described previously27. Brains were manipulated, imaged by confocal microscopy and tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons counted under blinded conditions.

Western blotting

Proteins were resolved by either 12% or 15% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked by PBS-T BSA (5%) for 1hr. Antibodies were incubated in blocking solution at a 1:1000 dilution (with the exception of anti-Actin - 1:10000, for 1hr) overnight at 4°C, washed repeatedly in PBS-T. Incubation with secondary antibody was carried out with either anti-mouse or anti-rabbit, HRP-conjugated antibody. Detection was carried out by ECL-Plus detection kit (Amersham) and comparative protein levels were quantified by densitometry using Image-J.

Antibodies

anti-phosho 4E-BP(Thr/Ser 37/46), anti-non-phospho 4E-BP, anti-phosho Akt1 and anti-Akt1 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies and anti-Actin from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-GstS145 was a kind gift from H. Benes (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences). Anti-Parkin has been previously described13.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA from live cells/flies was prepared from three to four replicates of each genotype/treatment, using TRIzol reagent (Sigma). The purity of RNA was then determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop). Once treated with DNase, total RNA was reverse-transcribed using RETROscript (Ambion) according to the manufacturers protocol. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green (Sigma) on a MyiQ real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Each PCR included three or four biological replicates, which were repeated three times (technical replicates). For each transcript, levels were normalized to a GAPDH control by the 2-ΔΔCT method. The following primer pairs were used:

Gapdh-F; GCGAACTGAAACTGAACGAG

Gapdh-R; CCAAATCCGTTAATTCCGAT

RpL32-F; GACGCTTCAAGGGACAGTATCTG

RpL32-R; AAACGCGGTTCTGCATGAG

parkin-F; AATGAAACTCTGTTGGACTTGC

parkin-R; CGGACTCTTTCTTCATCGCT

Thor-F; TCCTGGAGGCACCAAACTTA

Thor-R; AGCGACTTGGTCTGCTTGAT

Atg5-F; GACATCCAACCGCTCTGCGCA

Atg5-R; GGTGTACGTGAAGTCATCGTCTG

Cell culture

Drosophila S2R+ cells were grown in Schneider’s medium (Gibco) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma). dsRNA was generated, as per manufacturers protocols, using the MEGAscript T7 in vitro transcription kit (Ambion). 15μg of dsRNA was added in serum free media to S2R+ cells (1.2×106/ml) for 1h, after which cells were incubated (3d) at 25°C. Control cells were treated with dsRNA against DsRed. The following primer pairs were used to generate dsRNAs:

parkin-F, TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTGTTGCAATTTGGAGGGA

parkin-R, TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTTGGCACGGACTCTTTCT

DsRed-F; TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAAGGTGTACGTGAAGCACCC

DsRed-R; TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTAGTCCTCGTTGTGGGAGGT

Rapamycin (50nM) treatment was carried out on individual imaging dishes for 48hr prior to imaging. Rapamycin containing medium was first removed and replaced with medium containing 200μm Rhodamine-123 (40s). Cells were then repeatedly washed and finally the original, Rapamycin containing, medium was replaced.

Mitochondrial Morphology Assessment

Fibroblasts were stained with the fluorescent dye rhodamine 123, plated as previously described12. Mitochondria were then imaged using a Delta-vision RT microscope (Drosophila cells) or a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Fibroblasts). n ≥ 45 cells per condition. Raw images were binarized and mitochondrial morphological characteristics (aspect ratio and number per cell) were quantified as described previously50.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

Fibroblasts were cultured from 2 patients with parkin mutations and 3 normal controls. Fibroblasts were plated at 40% confluency in 96 well plates; 24 hours later cells were changed into galactose culture medium as described previously12. The mitochondrial membrane potential was then measured using the fluorescent dye Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) after a further 24h as described previously12. In order to remove the plasma membrane contribution to the TMRM fluorescence, each assay was performed in parallel as earlier plus 10μM carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), which collapses the mitochondrial membrane potential. All data is expressed as the total TMRM fluorescence minus the CCCP treated TMRM fluorescence. Cell number was measured using the ethidium homodimer fluorescent dye in a parallel plate after freeze thawing.

Statistical Analyses

Viability and indentation counts

Statistical significance was carried out on individual genotypes using Mann-Whitney non-parametric analysis as data failed to achieve normality.

Flight and climbing

n ≥ 30 per genotype, typically ~100. Statistical significance was calculated by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric analysis and Dunn’s pair-wise comparison.

Dopaminergic neuron counts

n ≥10 per genotype. Data was analyzed by Student t-test, with Bonferroni correction.

Western blot and qPCR

Analysis were carried out on three or more biological replicates and analysis was carried using two-tailed Student t-tests.

Mitochondrial analysis

As data failed to achieve normality, analysis of Drosophila mitochondrial morphology was carried out using Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric analysis and Dunn’s pair-wise comparisons. To account for multiple patient cell lines, analysis of fibroblast mitochondrial morphology/membrane potential was carried out using two-way ANOVA.

All statistical significance was calculated at p = 0.05, using GraphPad Prism 5.

References

- 1.Abou-Sleiman PM, Muqit MM, Wood NW. Expanding insights of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:207–219. doi: 10.1038/nrn1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrer MJ. Genetics of Parkinson disease: paradigm shifts and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:306–318. doi: 10.1038/nrg1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark IE, et al. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, et al. Mitochondrial pathology and muscle and dopaminergic neuron degeneration caused by inactivation of Drosophila Pink1 is rescued by Parkin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10793–10798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602493103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Exner N, et al. Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:12413–12418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitworth AJ, Wes PD, Pallanck LJ. Drosophila models pioneer a new approach to drug discovery for Parkinson’s disease. Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03693-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitworth AJ, et al. Rhomboid-7 and HtrA2/Omi act in a common pathway with the Parkinson’s disease factors Pink1 and Parkin. Dis. Model Mech. 2008;1:168–174. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tain LS, et al. Drosophila HtrA2 is dispensable for apoptosis but acts downstream of PINK1 independently from Parkin. Cell Death Differ. 2009 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.23. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poole AC, et al. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1638–1643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, et al. Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7070–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711845105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortiboys H, et al. Mitochondrial function and morphology are impaired in parkin-mutant fibroblasts. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:555–565. doi: 10.1002/ana.21492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene JC, Whitworth AJ, Andrews LA, Parker TJ, Pallanck LJ. Genetic and genomic studies of Drosophila parkin mutants implicate oxidative stress and innate immune responses in pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:799–811. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemens MJ. Translational regulation in cell stress and apoptosis. Roles of the eIF4E binding proteins. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2001;5:221–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2001.tb00157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holcik M, Sonenberg N. Translational control in stress and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:318–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter JD, Sonenberg N. Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature. 2005;433:477–480. doi: 10.1038/nature03205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev. 2001;15:807–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.887201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernal A, Kimbrell DA. Drosophila Thor participates in host immune defense and connects a translational regulator with innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6019–6024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100391597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapahi P, et al. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teleman AA, Chen YW, Cohen SM. 4E-BP functions as a metabolic brake used under stress conditions but not during normal growth. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1844–1848. doi: 10.1101/gad.341505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tettweiler G, Miron M, Jenkins M, Sonenberg N, Lasko PF. Starvation and oxidative stress resistance in Drosophila are mediated through the eIF4E-binding protein, d4E-BP. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1840–1843. doi: 10.1101/gad.1311805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi S, et al. ATF4-mediated induction of 4E-BP1 contributes to pancreatic beta cell survival under endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 2008;7:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holcik M, Sonenberg N, Korneluk RG. Internal ribosome initiation of translation and the control of cell death. Trends Genet. 2000;16:469–473. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imai Y, et al. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP by LRRK2 affects the maintenance of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2008;27:2432–2443. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitworth AJ, et al. Increased glutathione S-transferase activity rescues dopaminergic neuron loss in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8024–8029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501078102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puig O, Marr MT, Ruhf ML, Tjian R. Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2006–2020. doi: 10.1101/gad.1098703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Southgate RJ, et al. FOXO1 regulates the expression of 4E-BP1 and inhibits mTOR signaling in mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21176–21186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy CT, et al. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:277–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McElwee JJ, et al. Evolutionary conservation of regulated longevity assurance mechanisms. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R132. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giannakou ME, et al. Long-lived Drosophila with overexpressed dFOXO in adult fat body. Science. 2004;305:361. doi: 10.1126/science.1098219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwangbo DS, Gershman B, Tu MP, Palmer M, Tatar M. Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body. Nature. 2004;429:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature02549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beretta L, Gingras AC, Svitkin YV, Hall MN, Sonenberg N. Rapamycin blocks the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and inhibits cap-dependent initiation of translation. EMBO J. 1996;15:658–664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunn GJ, et al. Phosphorylation of the translational repressor PHAS-I by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Science. 1997;277:99–101. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burnett PE, Barrow RK, Cohen NA, Snyder SH, Sabatini DM. RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1432–1437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gloeckner CJ, et al. The Parkinson disease causing LRRK2 mutation I2020T is associated with increased kinase activity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:223–232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West AB, et al. Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16842–16847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507360102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gingras AC, et al. Hierarchical phosphorylation of the translation inhibitor 4E-BP1. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2852–2864. doi: 10.1101/gad.912401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muftuoglu M, et al. Mitochondrial complex I and IV activities in leukocytes from patients with parkin mutations. Mov. Disord. 2004;19:544–548. doi: 10.1002/mds.10695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King MA, et al. Rapamycin inhibits polyglutamine aggregation independently of autophagy by reducing protein synthesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;73:1052–1063. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wyttenbach A, Hands S, King MA, Lipkow K, Tolkovsky AM. Amelioration of protein misfolding disease by rapamycin: translation or autophagy? Autophagy. 2008;4:542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.6059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott RC, Schuldiner O, Neufeld TP. Role and regulation of starvation-induced autophagy in the Drosophila fat body. Dev Cell. 2004;7:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh SP, Coronella JA, Benes H, Cochrane BJ, Zimniak P. Catalytic function of Drosophila melanogaster glutathione S-transferase DmGSTS1-1 (GST-2) in conjugation of lipid peroxidation end products. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2912–2923. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, et al. Mutant LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nn.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greene JC, et al. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:4078–4083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Junger MA, et al. The Drosophila forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J. Biol. 2003;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miron M, et al. The translational inhibitor 4E-BP is an effector of PI(3)K/Akt signalling and cell growth in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:596–601. doi: 10.1038/35078571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Vos KJ, Sheetz MP. Visualization and quantification of mitochondrial dynamics in living animal cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;80:627–682. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.