Abstract

MAP kinase ERK maintains specificity by binding to docking sites such as the DEF domain or D domain. It was previously shown that appending peptides derived from D domains to a substrate peptide increased apparent efficiency of peptide phosphorylation while preserving its apparent specificity for ERK. Here we determine the effect of the DEF motif on efficiency and specificity of peptide phosphorylation by ERK. The DEF motif modulated the apparent affinity of the peptide for ERK while the substrate motif dominated the apparent catalytic rate. Attachment of the DEF sequence improved apparent phosphorylation efficiency by 60-fold. Addition of peptides possessing both the DEF and D motif to a substrate sequence did not yield additive effects on the KM of the substrate for ERK. Further, the DEF motif diminished the apparent specificity for ERK and increased the apparent efficiencies of phosphorylation of the substrate peptide by p38α kinase and JNK1.

Keywords: MAP kinase, docking motifs, FXFP motif, peptide substrates

The Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinases (ERKs), are mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases involved in the regulation of cellular activities such as gene expression, mitosis, meiosis and movement [1, 2]. ERK is activated by a sequential cascade of enzymes consisting of the Ras G-proteins, Raf kinases, and MAP kinase kinase 1 and 2 (MEK1 and 2). MEK1 and 2 phosphorylate and activate MAP kinases, ERK1 and 2 [3]. Various transcription factors such as the ELK and ETS family of proteins that regulate cell growth are then phosphorylated by ERK1 and 2 [4, 5].

Since multiple signaling proteins are present in the same cell, a mechanism must exist to activate only the appropriate signaling pathways in response to stimuli. The specificity of kinases was initially thought to be determined primarily by the complementarity of the substrate with the kinase active site. Although active sites of protein kinases possess preferred amino acid sequences adjacent to the phosphorylated residue, these preferences alone cannot explain the specificity of kinases for their natural substrates. For example, ERK is a serine/threonine kinase with a phosphorylation consensus motif of Ser/Thr-Pro [5, 6]. However, since other MAP kinases (p38 kinase and JNK) as well as cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) also phosphorylate the same sequence, this motif alone cannot explain the specificity achieved by ERK [6]. Specificity and efficiency of ERK for its substrates is thought to be determined by high-affinity, binding motifs on the substrate that are distinct from the consensus phosphorylation sequence [7-11]. A major ERK-binding motif identified on substrates and activators of ERK is the D domain. D domains possess a consensus binding sequence of (Arg/Lys)2-3-(X)1-6-Φ-X-Φ; where Φ is a hydrophobic residue such as Leu, Ile, Val and X is any amino acid [7-11]. The D domain of substrates and ERK activators binds to a complementary docking site on ERK composed of a highly acidic patch and a hydrophobic groove [7-11]. Many substrates also have a second ERK-binding region, the DEF motif which possesses a consensus sequence of F-X-F-P [7, 12, 13]. This motif has been identified in several substrates of ERK, including ELK1, SAP1 and KSR [7, 11-13]. Originally, the DEF domain was thought to mediate interactions with ERK exclusively. However, recent studies have shown that this sequence also serves as a binding site for p38α MAP kinase [13]. The DEF domain of substrates binds to a region of ERK adjacent to the catalytic cleft while the D domain makes contact with ERK on the opposite face of the kinase relative to the catalytic site [11]. Both the D and DEF motifs may exist within a single substrate as for the transcription factor ELK1. In substrates that contain both the docking sites, the sites are thought to function additively to create a high-affinity interaction with ERK.

Fernandes et. al demonstrated that appending a short docking sequence derived from the D domain of either the downstream substrate or activator of ERK to a peptide containing the phosphorylation sequence increased apparent affinity of ERK for the phosphorylation sequence by 200-fold while only slightly diminishing apparent maximal velocity of the reaction [14]. Apparent efficiency of the phosphorylation reaction was increased by 150-fold while the apparent specificity for ERK was preserved [14]. A goal of the current work was to evaluate the influence of the DEF sequence with and without the D domain sequence on the affinity, specificity and efficiency of a substrate peptide for ERK. A series of peptide substrates incorporating either the D motif, the DEF motif, or both were designed and tested. The KM, Vmax and kcat of each substrate for ERK were measured. To determine the specificity of the substrates for ERK, reaction constants were also measured p38α kinase and JNK1. The characterization of these docking sites when attached to simple peptide substrates will improve the understanding of the interaction between ERK and its substrates. In addition, highly efficient and specific peptide substrates can serve as components of indicators or reporters for in vivo use [15, 16].

Materials and Methods

Materials

Competent E coli cells (strain BL21 DE3) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Ni-NTA agarose columns were from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) while fused silica capillaries were obtained from Polymicro Technologies (Phoenix, AZ). Purified, active JNK1 enzyme was purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA). All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Expression and Purification of Active ERKI and p38α

kinase. Active ERK1 and p38α kinase were expressed and purified using plasmids pETHis6MEK1 R4F+ERK1 and pETHis6/MEK6DD+p38α respectively [14, 17].

Peptide Synthesis and Preparation

Peptides labeled on the N-terminus with fluorescein and amidated on the C-terminus were synthesized by Anaspec Inc. (San Jose, CA). Concentration of peptides was determined by amino acid analysis carried out by the Molecular Structure Facility at the University of California in Davis [18].

Measurement of Peptide Phosphorylation

The Immobilized Metal Ion Affinity-Based Fluorescence Polarization assay (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) was used to measure amount of phosphorylated peptide in reaction mixtures as described previously [14, 19]. Protein kinase assays were performed at 30°C in assay buffer [10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.2), 1 mM DTT, 0.01 % Tween 20 and 0.05% NaN3] with 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP and 1 nM ERK1, 0.7 nM p38α kinase or 0.7 nM JNK1[14, 19]. Initial reaction velocity was measured in reaction mixtures in which less than 10% of the substrate was consumed. The velocity was plotted against substrate concentration and fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Results and Discussion

Design of Docked Substrates for ERK

The designed ERK substrates possessed two or more of the following components: an N-terminal fluorescein, a D-motif peptide, a substrate sequence, a DEF-motif peptide, and linkers between the components. Fluorescein (5-FAM) facilitated peptide detection. The substrate sequence (TGPLSPGPF) was selected to match the consensus motif identified in protein substrates of ERK [5, 6]. This substrate sequence also possessed a proline at the P+2 position which enhances the Vmax for phosphorylation by ERK [20]. The KM and kcat of the substrate sequence for ERK1 were reported previously as 127 μM and 250 min-1 respectively [14]. In prior work a D docking peptide (MPKKKPTPIQLNP) derived from the N-terminus of MAP kinase kinase, MEK1, was tethered by three units of 8-amino-3, 6-dioxaoctanoyl (AOO) to the N-terminus of the substrate sequence (Table 1) [14]. This D-domain-substrate construct possessed a KM of 3 μM for ERK, a nearly 50-fold improvement relative to the substrate sequence alone. Thus this peptide was used as the D-domain-substrate peptide for this work.

Table 1.

Designed peptide substrates for ERK

| Substrate Name | Amino acid sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D motif | Linker | Consensus motif | Linker | DEF motif | |

| ERKSub | aTGPLSPGPFc | ||||

| MEK1ERK | aMPKKKPTPIQLNP | (AOO)3 | TGPLSPGPFc | ||

| ERKFXFP | aTGPLSPGPF | (AOO)2 | FQFPc | ||

| MEK1ERKFXFP | aMPKKKPTPIQLNP | (AOO)3 | TGPLSPGPF | (AOO)2 | FQFPc |

The N-terminus was covalently attached to fluorescein

(AOO) is the linker, 8-amino-3,6-dioxaoctanoyl

The C-terminus was amidated.

The DEF sequence, FQFP, is found in a variety of ERK substrates [7]. The C-terminus of transcription factors like LIN1, ELK1 and SAP1 possess this sequence which was identified as being both necessary and sufficient to mediate high affinity interactions with ERK [7]. FQFP-containing peptides have also been shown to inhibit phosphorylation of substrates by ERK in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that these short peptide substrates may bind to ERK [7]. Hence, the docking peptide “FQFP” was used as the DEF domain sequence in the modular ERK substrates. The region where the DEF motif binds to ERK was identified by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry using the ELK1-derived peptide “AKLSFQFPS” [11]. These studies suggested that the N-terminus of the FQFP peptide in the designed ERK substrates should extend from the C-terminus of the substrate peptide with a linker length equivalent to six amino acids. Since AOO is a neutral, hydrophilic molecule with good flexibility and has worked well as a linker for the D-domain-substrate peptide, two units of AOO equivalent in length to 6 amino acids (~20Å) were used as a linker between the substrate and FQFP sequence in the designed substrate. FQFP-containing substrate peptides with and without an N-terminal D-domain sequence from MEK1 were also synthesized (Table 1).

Phosphorylation of the Designed Substrates by ERK

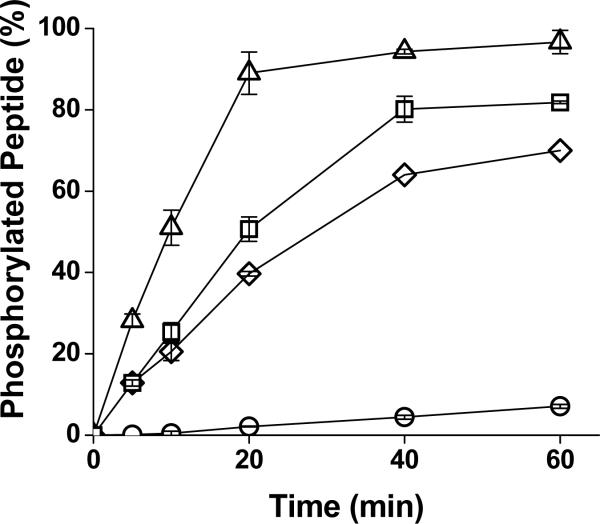

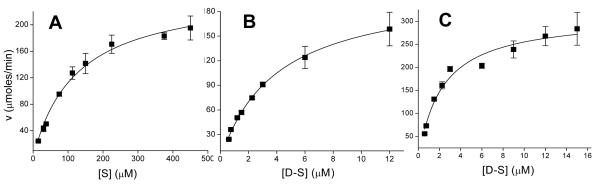

To compare rates of phosphorylation of the designed substrates, the peptides (1 μM) were incubated with ERK1. Aliquots were removed at various times and amount of phosphorylated peptide was measured. The substrate with the least phosphorylation at any given time was the substrate peptide alone (Figure 1). Addition of either of the docking peptides dramatically enhanced phosphorylation of the substrate peptide. Surprisingly, addition of the FQFP alone to the substrate yielded the most rapid peptide phosphorylation with nearly 100% of the peptide phosphorylated in 20 mins. This suggested that the FQFP sequence was appended to the substrate in the proper orientation and with an adequate linker length. Addition of the D-domain sequence with or without an FQFP motif resulted in a lower amount of phosphate addition. These results suggested that the DEF and D motifs may not act in an additive fashion when attached to small peptide substrates with respect to ERK phosphorylation. To better understand the influence of the DEF motif on substrate phosphorylation by ERK, the reaction properties of the designed peptides were quantitated. Although the docked peptides have two or more binding sites to ERK1, when steady state kinetics were used to model the binding of these peptides to the kinase, the curve could be reduced to the following form: v = Vmaxapp*[D-S]/ (KMapp + [D-S]) for KMapp defined as the apparent KM and Vmaxapp defined as the apparent Vmax [14]. The initial reaction velocity (v) at varying peptide concentrations was measured and as with the substrate alone and D-domain-substrates, the substrates with the FQFP sequence also yielded vvs. [D-S] curves that were readily fit to this modified Michaelis-Menten equation (Figure 2). KMapp's of the peptides for ERK1 were derived from fits of the data to the modified equation (Table 2). Apparent affinities of all docked peptides (ERKFXFP, MEK1ERKFXFP and MEK1ERK) were similar and over 40-fold better than that of the KM of the substrate alone. Thus all docking sequences improved the apparent affinity of the substrate peptide for ERK1. These dramatic apparent affinity enhancements suggested that the docking peptides bound to the kinase and dominated on and/or off rates of the designed substrates. However under these conditions the use of two docking peptides did not have an additive effect on the KM.

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of the designed substrates by ERK1. The designed substrates (1 μM) (ERKFXFP triangles; MEK1ERKFXFP, squares; MEK1ERK, diamonds; ERKSub, circles) were incubated with ERK1. Aliquots were removed at varying time points and amount of phosphorylated peptide was measured. Data points represent average of three measurements and error bars indicate their standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Measurement of KMapp and Vmaxapp of the FQFP-linked substrates. A) Shown is the initial velocity (v) vs. substrate concentration [S] for ERKSub. B) and C) Shown is the initial velocity (v) vs. docked substrate concentration ([D-S]) curve for MEK1ERKFXFP (B) and ERKFXFP (C). Solid lines represent the fits to the Michaelis-Menten equation (A) or the modified Michaelis-Menten equation (B and C). Initial velocity v is reported per μmole of enzyme. Data points represent average of three measurements and error bars the standard deviation of the data.

Table 2.

Reaction constants of the designed peptides for ERK1, p38α kinase and JNK1

| ERK1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | KMapp (μM) | kcatapp (min-1) | kcatapp/KMapp (μM-1 min-1) |

| ErkSub | 123 ± 13 | 250 ± 20 | 2 |

| ErkFXFP | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 310 ± 13 | 140 |

| MEK1ERKFXFP | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 210 ± 17 | 53 |

| aMEK1ERK | 3.7 ± 3.3 | 120 ± 40 | 32 |

| p38α Kinase | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | KMapp (μM) | kcatapp (min-1) | kcatapp/KMapp (μM-1 min-1) |

| ErkSub | 402.6 ± 75 | 570 ± 185 | 0.5 |

| ErkFXFP | 9.4 ± 1.7 | 1469 ± 90 | 156 |

| MEK1ERKFXFP | 18.4 ± 2.5 | 2900 ± 200 | 160 |

| aMEK1ERK | 65 ± 14 | 570 ± 28 | 8.7 |

| JNK1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | KMapp (μM) | kcatapp (min-1) | kcatapp/KMapp (μM-1 min-1) |

| ErkSub | 2436 ± 1424 | 509 ± 248 | 0.2 |

| ErkFXFP | 630 ± 221 | 1248 ± 242 | 1.9 |

| MEK1ERKFXFP | 11 ± 2 | 2424 ± 191 | 220 |

| MEK1ERK | 51 ± 3 | 400 ± 68 | 7.8 |

MEK1ERK values as reported in Reference 14.

kcatapp of the Designed Peptide Substrates for ERK1

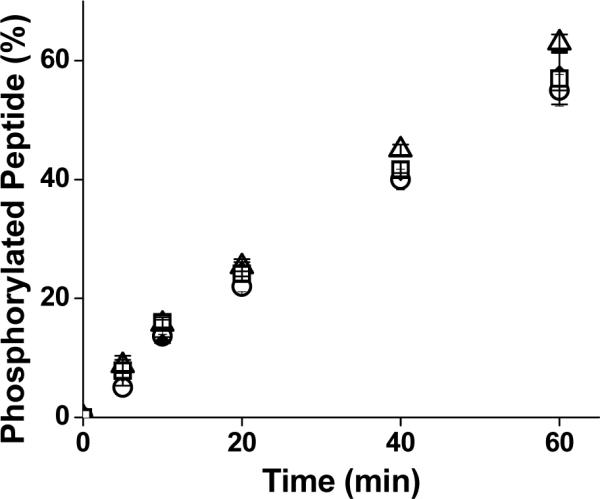

The Vmaxapp of the peptides for ERK1 was derived from fits of the data to the modified Michaelis-Menten equation and kcatapp then calculated using the measured enzyme concentration (Table 2). The kcatapp of ERKFXFP and MEK1ERKFXFP peptides which contain the C-terminal FQFP was similar to the kcat of the substrate alone. While the FQFP sequence significantly altered the apparent affinity of the substrate for ERK1, it did not substantially influence the apparent catalytic rate constant. This suggests that the (AOO) linker used to append the FQFP to the substrate did not limit the ability of the substrate to access the catalytic site of the kinase. This is in contrast to the measured kcatapp for the D-domain-docked substrate, MEK1ERK, which was decreased by a factor of two relative to the kcat of the substrate alone [14]. To determine whether the FQFP sequence alone could influence the activity of the kinase, the apparent catalytic rate constant for phosphorylation of ERKSub was measured in the presence and absence of free FQFP peptide. For FQFP concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 μM, the progress of the reaction was similar (Figure 3). As with the D-domain sequences, the binding of FQFP alone did not alter the activity of ERK1 [14]. These results suggest that the substrate peptide rather than FQFP peptide dominated the kinetics of phosphate transfer.

Figure 3.

Influence of free FQFP peptide on the phosphorylation of ERKSub by ERK1. The initial concentration of ERKSub was 150 μM. The reaction mixture contained 0 (triangles), 1 (diamonds), 10 (squares) or 100 (circles) μM of the FQFP peptide. Data points represent average of three measurements while error bars represent the standard deviation.

Apparent Efficiency of the Designed Peptide Substrates for ERK1

To determine which of the designed substrates was the most optimal substrate for ERK1, the apparent efficiency (kcatapp /KMapp) was calculated (Table 2). All docked substrate peptides possessed higher apparent efficiencies than the substrate peptide alone. Remarkably, addition of only the DEF motif to the substrate sequence yielded the most efficient ERK substrate with an apparent phosphorylation efficiency 70-fold greater than that of ERKSub and 4-fold enhanced relative to that of MEK1ERK. Addition of the DEF motif to MEK1ERK did not result in an additive effect with respect to apparent efficiency. Indeed the MEK1ERKFXFP peptide suffered a 3-fold decrease in apparent efficiency relative to the substrate peptide with only the DEF motif.

Reaction Constants of the Designed ERK Substrates for p38α Kinase and JNK1

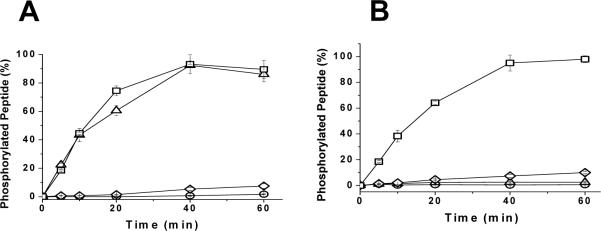

Since the consensus substrate sequence for all MAP kinases is similar, it was important to assess the suitability of the substrates for other MAP kinases. To compare rates of phosphorylation of the designed substrates, the peptides (1 μM) were incubated with either p38α kinase or JNK1. Aliquots were removed at various times and the amount of phosphorylated peptide was measured (Figures 4A and 4B). Addition of FQFP to either ERKSub or MEK1ERK dramatically increased the ability of p38α kinase to phosphorylate these substrates. FQFP-linked peptides were completely phosphorylated within 60 mins while peptides without this motif experienced little phosphorylation (less than 10% in 60 mins). These results are consistent with reports demonstrating that the DEF motif plays a role in phosphorylation of the transcription factor SAP-1 by p38α kinase and a recent report of peptides with the DEF motif being efficiently phosphorylated by p38α kinase [13, 21]. In contrast, the D-domain motif for ERK is similar but distinct from the D-domain motif for p38α kinase consistent with poor phosphorylation of MEK1ERK by p38α kinase [14]. Addition of the DEF motif alone was insufficient to enhance the apparent phosphorylation rate by JNK1 (Figure 4B). However, addition of both the D domain motif and the DEF motif together dramatically enhanced the phosphorylation of the peptide. The peptide MEK1ERKFXFP which contains both motifs was completely phosphorylated within 60 min while peptides with one or no docking motifs experienced little phosphorylation (less than 10% in 60 min). The initial reaction velocity was measured at varying substrate concentrations for phosphorylation by p38α kinase and JNK1. The curves of v vs. [D-S] possessed a shape similar to that yielded by the Michaelis-Menten equation (Supplementary Figure 1 and 2). Therefore the KMapp and Vmaxapp were determined from fits of the data to the modified Michaelis-Menten equation (Table 2) and kcatapp was calculated using the measured enzyme concentration(Table 2). Addition of the DEF motif greatly improved both the KMapp and kcatapp of the peptides for p38α kinase. The FQFP motif increased KMapp for p38α kinase by 40-fold relative to that of ERKSub. Relatively modest improvements (3 to 5-fold) in kcatapp were achieved for the FQFP-possessing peptides with respect to ERKSub. As a result of the increased apparent affinity, the efficiency of FQFP-linked substrates for p38α kinase increased by over 300-fold with respect to ERKSub. Thus, the substrate with the DEF motif peptide had similar apparent efficiencies for ERK and p38α kinase and exhibited no specificity for ERK over p38α kinase. Surprisingly the DEF motif influenced both KMapp and kcatapp of the docked peptide substrates for JNK1. The DEF motif slightly improved KMapp of the docked peptide (Table 2). However, kcatapp of the peptides with the DEF motif was twice that of the peptides without it. The peptide with both the D and DEF motif had an apparent efficiency 1000-fold higher than the substrate peptide alone [17]. Although the DEF motif influenced both KMapp and kcatapp, the KMapp of the peptides for JNK1 was influenced to a larger extent by the D domain derived sequence. This large improvement in KMapp due to the attachment of a D domain derived sequence of ERK is explained by the fact that both ERK and JNK1 interact with substrates such as the transcription factor ELK1 via its D domain [22]. Indeed, the docking peptide MEK1ERK (MPKKKPTPIQLNP) is very similar to the docking sequence of ELK1 (QKGRKPRDLELPLS) which interacts with both JNK1 and ERK. The affinity of the D domain docking peptide for JNK1 was however 10-fold lower than that for ERK. The increase in KMapp and kcatapp due to the DEF motif is very surprising since these results are in contrast to that reported [7]. The DEF motif is said to mediate interactions exclusively between ERK and its substrates and less frequently between p38α kinase and its substrates [7, 9, 13, 22]. Jacobs et al. reported that the DEF motif does not influence the affinity of ELK1 for JNK and ELK1 is reported to interact with JNK exclusively via its D domain [7]. However, no data regarding the catalytic rate constant was presented for JNK [7]. In addition, the separation distance between the phosphoacceptor and the DEF motif utilized by Jacobs et al. was shorter (10Å) than the distance used in the current docked peptides (20 Å). The longer linker utilized here may have enabled the FXFP to interact with the appropriate binding site on JNK. Notably Yang et al. demonstrated that ELK1 with D-domain mutations was phosphorylated to nearly the same extent by JNK and ERK [22]. Hence, there is a possibility that JNK may have a FQFP binding site that assists in aligning or orienting the substrate when it binds to JNK.

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of the FXFP substrates by p38α kinase and JNK1. The designed substrates (1 μM) were incubated with the respective MAP kinase in the presence of ATP and Mg2+. Aliquots were removed at varying time points and amount of phosphorylated peptide was measured. A) Phosphorylation of the FXFP substrates by p38α kinase. Substrates with the most phosphorylation were ERKFXFP (triangles) and MEK1ERKFXFP (squares). Substrates with the longest time for phosphorylation were MEK1ERK (diamonds) and ERKSub (circles). B) Phosphorylation of the FXFP substrates by JNK1. Substrate with the most phosphorylation was MEK1ERKFXFP (squares). Substrates with the least phosphorylation was ERKFXFP (triangles), MEK1ERK (diamonds) and ERKSub (circles). Data points represent average of three measurements and error bars indicate their standard deviation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge M. Cobb (University of Texas Southwestern) for supplying us with the plasmids for expression of active ERK and p38α kinases. This work was supported by grants from NSF and NIH (EB004597).

Abbreviations

- ERK

extracellular signal regulated kinase

- MAP

mitogen activated protein

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase

- His6

hexahistidine

- FAM

fluorescein

- AOO

8-amino dioxaoctanoic acid

- PDB

protein data bank

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Data Plots of initial velocity (v) vs substrate concentration [D-S] for the designed peptide substrates with p38α kinase and JNK1.

References

- [1].Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways Mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 Protein Kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nottage M, Siu LL. Rationale for Ras and raf-kinase as a target for cancer therapeutics. Curr Pharm Design. 2002;8:2231–2242. doi: 10.2174/1381612023393107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marshall CJ. MAP kinase kinase kinase, MAP kinase kinase and MAP kinase. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1994;4:82–89. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Crews CM, Alessandrini A, Erikson RL. Erks: their fifteen minutes has arrived. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Davis RJ. The mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J. Biol Chem. 1993;268:14553–14556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Songyang Z, Lu KP, Kwon YT, Tsai LH, Filhol O, Cochet C, Brickey DA, Soderling TR, Bartleson C, Graves DJ. A structural basis for substrate specificities of protein Ser/Thr kinases: primary sequence preference of casein kinases I and II, NIMA, phosphorylase kinase, calmodulin-dependent kinase II, CDK5, and Erk1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6486–6493. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jacobs D, Glossip D, Xing H, Muslin AJ, Kornfeld K. Multiple docking sites on substrate proteins form a modular system that mediates recognition by ERK MAP kinase. Genes Dev. 1999;13:163–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tanoue T, Adachi M, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. A conserved docking motif in MAP kinases common to substrates, activators and regulators. Nature Cell Biology. 2000;2:110–116. doi: 10.1038/35000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yang SH, Yates PR, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ, Sharrocks AD. The Elk-1 ETS-Domain Transcription Factor Contains a Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Targeting Motif. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:710–720. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sharrocks AD, Yang SH, Galanis A. Docking domains and substrate-specificity determination for MAP kinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:448–453. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee T, Hoofnagle AN, Kabuyama Y, Stroud J, Min X, Goldsmith EJ, Chen L, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Docking motif interactions in MAP kinases revealed by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fantz DA, Jacobs D, Glossip D, Kornfeld K. Docking Sites on Substrate Proteins Direct Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase to Phosphorylate Specific Residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:27256–27265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Galanis A, Yang SH, Sharrocks AD. Selective Targeting of MAPKs to the ETS Domain Transcription Factor SAP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:965–973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fernandes N, Bailey DE, VanVranken DL, Allbritton NL. Use of Docking Peptides to Design Modular Substrates with High Efficiency for Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase. ACS Chemical Biology. 2007;2:665–673. doi: 10.1021/cb700158q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Meredith G, Sims CE, Soughayer JS, Allbritton NL. Measurement of kinase activation in single mammalian cells. Nature Biotech. 18:309–312. doi: 10.1038/73760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sharma V, Agnes RS, Lawrence DS. Deep quench: An expanded dynamic range for protein kinase sensors. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 129:2742–2743. doi: 10.1021/ja068280r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Khokhlatchev A, Xu S, English J, Wu P, Schaefer E, Cobb MH. Reconstitution of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation cascades in bacteria. Efficient synthesis of active protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:11057–11062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cooper C, Packer N, Williams K. Amino Acid Analysis Protocols, in Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press; Totawa, New Jersey: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [19]. http://www.moleculardevices.com/pages/reagents/imap.html.

- [20].Clark-Lewis I, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL. Definition of a consensus sequence for peptide substrate recognition by p44mpk, the meiosis-activated myelin basic protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:15180–15184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sheridan DL, Kong Y, Parker SA, Dalby KN, Turk BE. Substrate Discrimination among Mitogen-activated Protein Kinases through Distinct Docking Sequence Motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:19511–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yang SH, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ, Sharrocks AD. Differential targeting of MAP kinases to the ETS-domain transcription factor Elk-1. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17:1740. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.