Abstract

Objective

The hypothesis is that partial nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) inhibition can alleviate cardiopulmonary dysfunction associated with ischemia and reperfusion injury following CPB/DHCA in a pediatric model.

Design

Animal case study.

Subjects

Two week-old piglets (5–7 kg).

Interventions

Piglets received 100 mcg•kg−1 of SN50, a peptide inhibitor of NF-κB translocation and activation, 1 hr before CPB. The control group received saline. Animals were cooled to 18oC with CPB, the piglets were in DHCA for 120 min, and were then rewarmed on CPB to 38°C and maintained for 120 min after CPB/DHCA.

Measurements

Sonomicrometry and pressure catheters collected hemodynamic data. Transmural left and right ventricular tissues were obtained at the terminal time point for determination of NF-κB activity by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Main Points

Oxygen delivery was maintained at 76±13 mL•min−1 at baseline and 75±5 mL•min−1 at 120 min after CPB/DHCA (P=.75) in SN50-treated animals vs. 99±26 mL•min−1 at baseline and 63±20 mL•min−1 at 120 min in the untreated group (P=.0001). Pulmonary vascular resistance (dynes•s−1•cm−5) increased from 124±59 at baseline to 369±104 at 120 min in the untreated piglets (P=.001) compared with SN50-treated animals (100±24 at baseline and 169±88 at 120 minutes, P=.1). NF-κB activity was reduced 74% in left ventricles of SN50-treated compared with untreated animals (P<.001). Plasma endothelin-1 (pg•mL−1), an important vasoconstrictor regulated by NF-κB, increased from 2.1±0.4 to 14.2±5.7 in untreated animals (P=.004) but was elevated to only 4.5±2 with SN50 treatment (P=.005).

Conclusions

Improvement of cardiopulmonary function after ischemia/reperfusion was associated with the reduction of NF-κB activity in piglet hearts. Maintenance of systemic oxygen delivery and alleviation of pulmonary hypertension after CPB/DHCA in piglets administered SN50, possibly through a reduction of circulating endothelin-1, suggest that selective inhibition of NF-κB activity may reduce ischemia and reperfusion injury after pediatric cardiac surgery.

Keywords: nuclear factor-kappaB, ischemia, reperfusion injury, cardiopulmonary bypass, calpain, troponin I

Introduction

Ischemia and reperfusion injury to the immature myocardium that occurs during repair of congenital heart disease remains a significant contributor to perioperative morbidity and mortality. Despite the use of inotropes in the post-operative period, a low cardiac output state may occur in up to 30% of neonates and infants. Underlying this process is overall myocardial depression including both systolic and diastolic dysfunction. While often transient, more permanent injury in the form of necrosis and/or apoptosis might occur. Pulmonary dysfunction is frequently present and added to the myocardial dysfunction exacerbates the low cardiac output state.

We have previously demonstrated that administration of glucocorticoids, which maintain the cellular levels of the endogenous calpain inhibitor calpastatin (1, 2), or the administration of a peptide calpain inhibitor (3) markedly attenuates myocardial dysfunction and reduces pulmonary hypertension in a piglet model of cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA). The mechanism by which calpain inhibition improves cardiopulmonary function is not entirely known. A proposed mechanism is that increased calpain activity stimulates nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus where NF-κB binding to DNA leads to upregulation of various inflammatory and cell death regulators (4).

Calpains are calcium-dependent cysteine proteases regulated by the endogenous specific calpain inhibitor, calpastatin. Calpain-mediated cleavage regulates the activity of diverse substrates including kinases, cytoskeletal proteins, apoptotic cascade members, and anumber of transcription regulatory proteins, such as NF-κB. Calpain also systematicallydegrades troponin I (TnI), the inhibitory component of the cardiac troponin complex, which mediates calcium dependence of cardiac contraction (5). Selective proteolysis of TnI is proposed to lead to contractile dysfunction after myocardial reperfusion, resulting in myocardial stunning (6, 7) that can be limited through calpain inhibition (1).

In quiescent cells, NF-κB in the cytosol remains bound to the inhibitor kappa B (IκB) family of proteins. Upon stimulation IκB is phosphorylated and degraded by proteases, including calpain. Released NF-κB translocates to the nucleus and binds specific DNA sequences to regulate target genes. In some cell types NF-κB activation is markedly reduced by calpain inhibitors (8–10). Calpains might also inactivate NF-κB by directly proteolysis (4).

Regulation of programmed cell death by NF-κB appears to be a balance of pro- versus anti-cell survival signals (11). A basal level of NF-κB activity suppresses apoptosis and necrosis through expression of caspase inhibitors, anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, and antioxidants; but elevated NF-κB activity leads to inflammatory gene expression and cellular injury (12).

Endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor, is also regulated in part by NF-κB. In previous studies with glucocorticoid administration and calpain inhibition a reduction in pulmonary hypertension after CPB was associated with a decrease in plasma endothelin-1 (3, 13). In addition, an endothelin-1 receptor antagonist also ameliorated pulmonary hypertension associated with ischemia and reperfusion in the piglet model (14).

Previous studies by our research group indicate that glucocorticoids administered prior to CPB can alleviate CPB-DHCA-associated cardiopulmonary dysfunction. The improvement in function is accompanied by decreased calpain activity in the heart and lungs and maintenance of endogenous levels of calpastatin (1). Direct administration of a peptide inhibitor of calpain during CPB-DHCA also improved cardiopulmonary function and decreased NF-κB activity in the heart (3). Therefore, we conducted these experiments to determine whether administration of a NF-κB inhibitor to alleviate the CPB-DHCA-induced rise in NF-κB activity would reduce cardiopulmonary dysfunction and cellular injury in a piglet model of CPB-DHCA.

Methods

Animal Model

All animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care, formulated by the National Society for Medical Research, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, prepared by the Institute of Laboratory Animals Resources and published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 86–23, revised 1985). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation also approved the protocol.

Piglets weighing 5–7 kg were anesthetized, mechanically ventilated, and subjected to CPB and DHCA as previously described (1, 2, 13). Pentobarbital infusion (20 mg·kg−1·hr−1), intermittent fentanyl citrate (10 mcg·kg−1·hr−1) and pancuronium bromide (0.1 mg·kg−1·hr−1) were used with doses sufficient to maintain deep general anesthesia. Pressure catheters (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) were placed in the pulmonary artery and in the right and left ventricles (RV and LV). Six piezoelectric crystals were placed in the myocardium at the anterior, posterior, base and apex of the LV and at the widest point of RV and LV free walls. The distances between all six crystals on three axes were measured by sonomicrometry. Sonolab data collection and Cardiosoft analysis software monitored cardiac function (Sonometrics, ON, Canada). Pressure-volume loops generated during preload reduction by transient vena caval occlusion allowed for measures of cardiac contractility relatively independent of heart rate and afterload. Ventricular +/− dP/dt, LV Tau, oxygen delivery, and preload recruitable stroke work relationwere calculated. Respiratory function was monitored by CO2SMO Plusrespiratory profile system (Novametrix, Wallingford, CT). Dynamic compliance, airway resistance, and expired CO2 and O2 were monitored and pulmonary vascular resistance [80 * ((mean pulmonary artery pressure central venous pressure)/cardiac output)] was calculated. Baseline measurements of pulmonary and cardiac function are taken after a 30-minute equilibration period.

Animals were administered heparin and placed on CPB with cannulation via the carotid artery and right atrial appendage. The CPB prime consisted of 800 mL direct-drawn whole porcine blood (Animal Biotech Industries, Danboro, PA). Hematocrit on CPB was maintained at 25–30% and calcium at 0.6–0.8 mg·L−1 with a flow rate of 100 mL·kg−1·min−1. Once on CPB, animals were cooled to a rectal temperature of 18°C over approximately 40 minutes. The bypass circuit was then turned off and the animal packed in ice. The heart was protected with topical cold saline and ice. Circulatory arrest was maintained for 120 minutes. Cardiopulmonary bypass was re-instituted and the animals were warmed to 38°C over 45 minutes on CPB. Piglets were removed from CPB and maintained under anesthesia for 120 minutes. Blood gases were monitored periodically throughout the experiment (Bayer Diagnostics). Aortic and pulmonary arterial blood samples from each animal were collected at baseline, 1 hour, and 2 hours after CPB/DHCA.

Animals were randomly divided into the experimental groups:

no CPB/DHCA Controls (n=3),

CPB/DHCA Controls, no treatment (n=8), and

CPB/DHCA SN50, NF-κB translocation inhibitor administered before CPB/DHCA (n=6). Animals were administered a single dose of 100 mcg·kg−1 of SN50 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA), an inhibitor of NF-κB translocation, 1 hr before CPB by intravenous injection. This dose was selected from preliminary studies to reduce NF-κB activity in the heart 120 minutes after CPB/DHCA to near baseline levels without abolishing NF-κB activity.

Nuclear Factor kappaB Activity

Nuclear factor-κB activity in nuclear extracts (10 mcg) from the LV myocardium was assessed with a transcription factor assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Antibodies for the activated forms of the p50 and p65 (rel A) subunits of NF-κB were included in the assay. The detection limit for the assay is 0.4 ng recombinant p50 or p65 protein.

Endothelin-1 Measurements

Blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 4°C and plasma was frozen at −80°C for later analysis. A commercial endothelin-1 immunoassay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used to measure endothelin-1 concentration in plasma.

Myocardial Protein Immunoblot Analyses

Collected tissues were homogenized in 10 mmol/L 3-[N-morpholino] propane sulfonic acid buffer and stored at −80°C until used. Western blots were performed with 30 μg total proteins separated on 4–12% acrylamide bis-tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by SDS-PAGE then immunoblotted with antibodies for calpain I and II (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), calpastatin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), IκB-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Chemicon). Secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG. Proteins were visualized with a chemiluminescent detection system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Protein levels are reported as a ratio of target protein to GAPDH levels on the same immunoblot to correct for background effects.

Troponin I Degradation

Troponin I degradation in adult stunned myocardium occurs as the result of activation of calpains (6) and our research group reported that TnI degradation occurred in this model after CPB/DHCA (1). Cardiac myofibrils were isolated from myocardial tissue collected at the end of the experiment (15). Myofibril proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked and incubated with TnI antibody recognizing all of the previously reported degradation products (Research Diagnostics, Inc, Flanders, NJ). Immunoblotting was carried out by standard chemiluminescent procedures. The degree of degradation was measured as the percent of total TnI in each immunoblot lane that was detectable in degraded and complexed bands.

Statistical Analysis of Data

Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to analyze serial data over time and post-hoc comparisons made by Fisher’s post hoc least significant difference test were used when appropriate to evaluate differences between individual time points within treatment groups. Comparisons between treatments were made by analysis of variance with a P value ≤ .05 considered significant. Personnel blinded to the treatment group status conducted analyses using Statview 4.01 software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). Data are reported as means ± standard deviations.

Results

Nuclear Factor-kappaB Activity

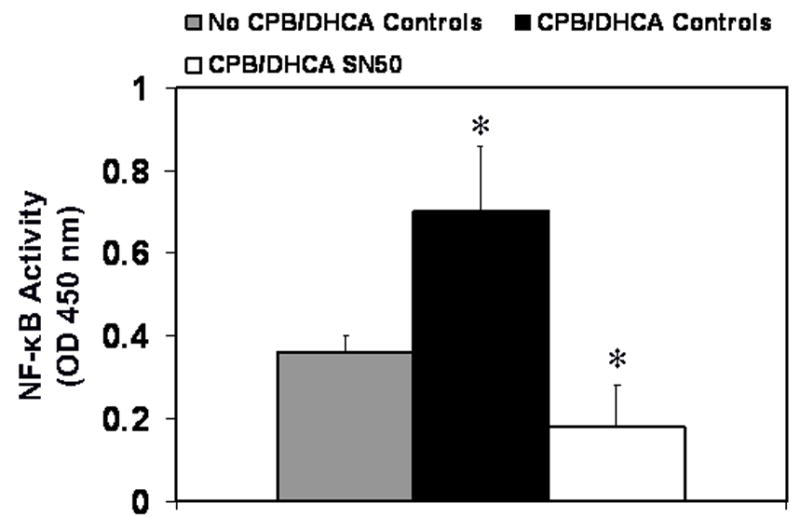

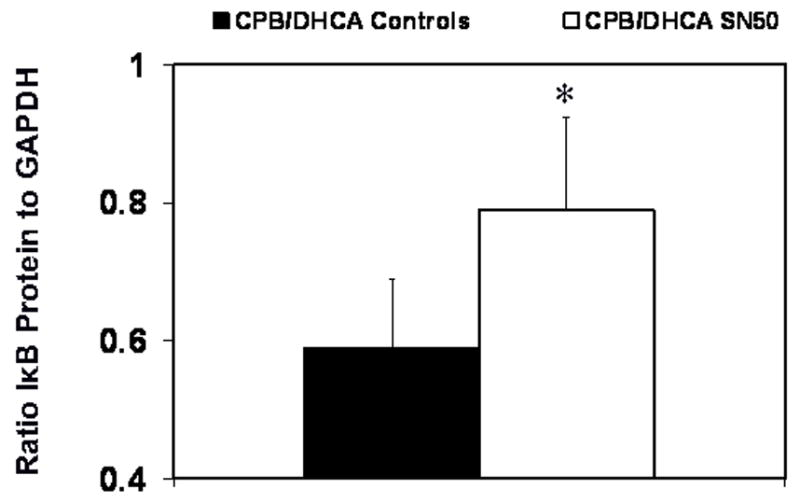

The administration of SN50 decreased NF-κB activity levels in nuclear extracts from LV myocardium 120 minutes after CPB/DHCA compared with CPB/DHCA controls (.18±.1 vs. .7±.16 absorbance units P<.001, Fig 1). Hearts from SN50-treated animals had NF-κB activity levels slightly lower than control animals that did not undergo CPB/DHCA (.18±.1 vs .368±.04 absorbance units, P=.05). Immunoblots of LV myocardial homogenates indicated that SN50 treatment maintained IκBα protein at higher levels than in untreated animals (.79±.14 vs .59±.14 ratio of target to GAPDH, P=.04) 120 minutes after CPB/DHCA (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Nuclear factor-κB activity in myocardium of the left ventricle from piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus no CPB/DHCA controls.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB protein (IκB) in myocardium of the left ventricle from piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus CPB/DHCA controls.

Cardiopulmonary Function

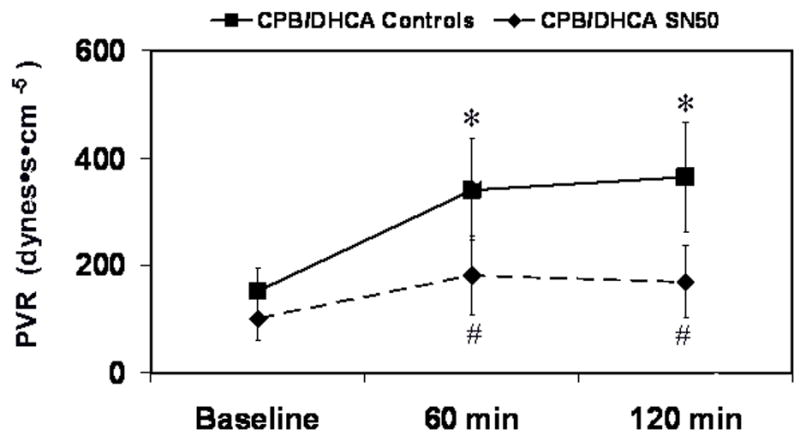

SN50 inhibition of NF-κB prevented the increase from baseline in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) associated with the CPB/DHCA untreated controls. In the CPB/DHCA SN50 group PVR (dyne·sec−1·cm−5) was not different at baseline compared with 120 minutes after CPB/DHCA (100±24 vs 169±88, P=.1). However, PVR in the CPB/DHCA controls increased from 124±59 at baseline to 369±104 at 120 minutes after CPB/DHCA (P=.001, Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus baseline within treatment groups; # P<.05 versus CPB/DHCA controls at the same time point.

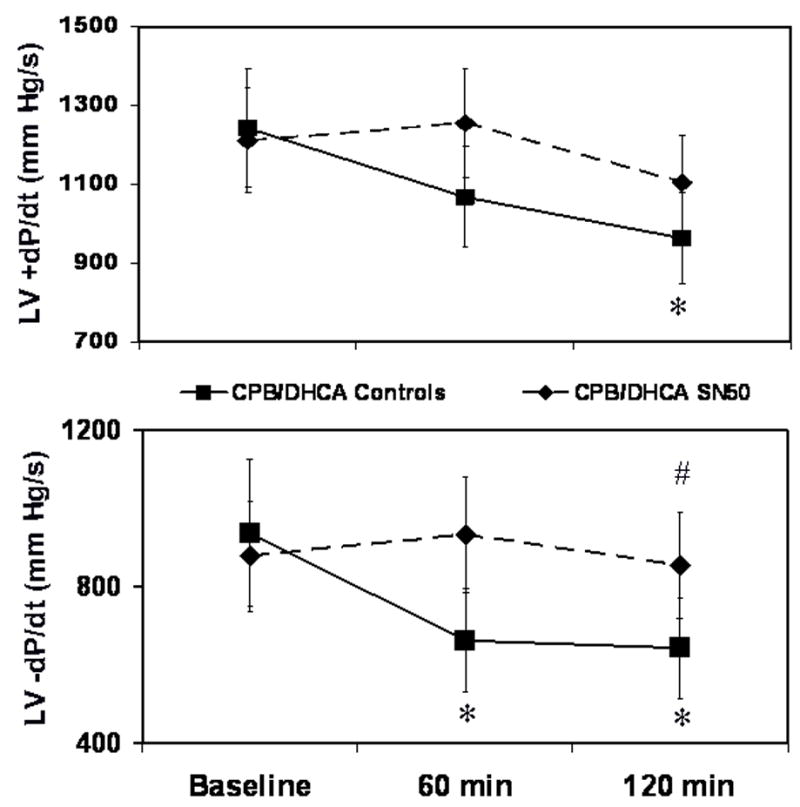

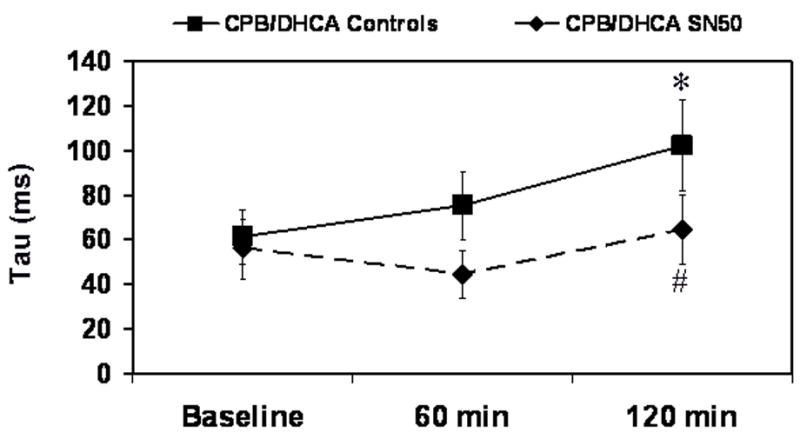

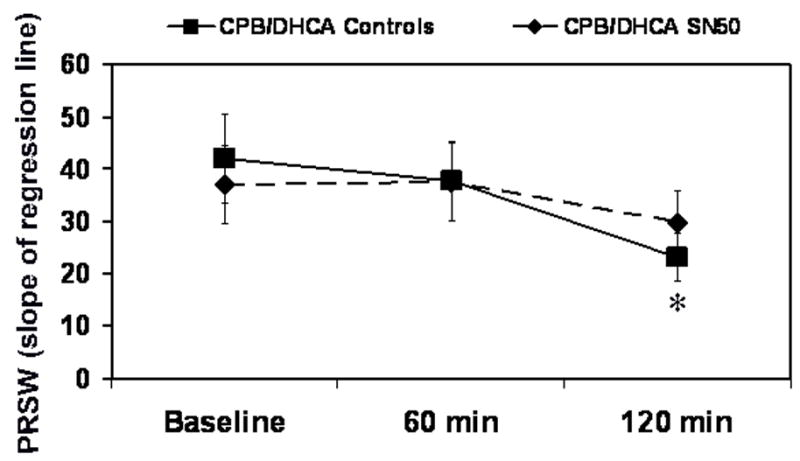

Myocardial contractile function, measured as LV maximum and minimum derivative of the change in pressure/derivative of the change in time (dP/dt), was preserved with SN50 administration after CPB/DHCA (Fig. 4). Maximum dP/dt in the CPB/DHCA controls decreased from 1243±242 mmHg·s−1 at baseline to 964±251 mmHg·s−1 at 120 min after CPB/DHCA (P=.04), while it did not differ in the SN50-treated animals (P=.09). Minimum dP/dt showed a similar trend. Left ventricular Tau, the time-constant of relaxation, was unchanged from baseline in SN50-treated animals (P=.06), whereas it was elevated from baseline (61.2±12 ms) at 120 min after CPB/DHCA (102.2±21 ms) in untreated animals (Fig 5). Preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW) was also better maintained in SN50 hearts compared to controls at 120 minutes after CPB/DHCA (Fig. 6). The depression in oxygen delivery in CPB/DHCA controls from baseline (99±26 mL·min−1) to 120 min after CPB (63±20 mL·min−1, P<.0001) was ameliorated with SN50 administration (76±13 mL·min−1 at baseline vs 75±5 mL·min−1 at 120 min after CPB/DHCA, P=.9). Cardiac function parameters are further defined in Table 1.

Fig 4.

Left ventricular maximum (upper panel) and minimum (lower panel) dP/dt levels in piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus baseline within treatment groups; # P<.05 versus CPB/DHCA controls at the same time point.

Fig 5.

Left ventricular Tau in piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus baseline within treatment groups; # P<.05 versus CPB/DHCA controls at the same time point.

Fig 6.

Preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW) in piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus baseline within treatment groups.

Table 1.

Cardiac Function

| Variable | Baseline | 60 min after CPB/DHCA | 120 min after CPB/DHCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen delivery (mL per min) | |||

| CPB/DHCA Controls | 99 ± 26 | 76 ± 26 a | 64 ± 21a |

| CPB/DHCA SN50 | 76 ± 13 | 84 ± 31 | 75 ± 5 |

| Mean Arterial Pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| CPB/DHCA Controls | 58 ± 7 | 41 ± 11a | 42 ± 11a |

| CPB/DHCA SN50 | 53 ± 4 | 47 ± 5 | 55 ± 6b |

| Cardiac Output (mL per min) | |||

| CPB/DHCA Controls | 561 ± 225 | 397 ± 168 | 313 ± 89a |

| CPB/DHCA SN50 | 415 ± 107 | 446 ± 55 | 372 ± 40 |

| Heart Rate (Beats per min) | |||

| CPB/DHCA Controls | 118 ± 22 | 156 ± 32a | 141 ± 20a |

| CPB/DHCA SN50 | 116 ± 14 | 169 ± 27a | 143 ± 12a |

Values are the means ± standard deviation of the mean.

different from baseline within treatment group (P < 0.05)

different from CPB/DHCA Controls at same time point (P < 0.05)

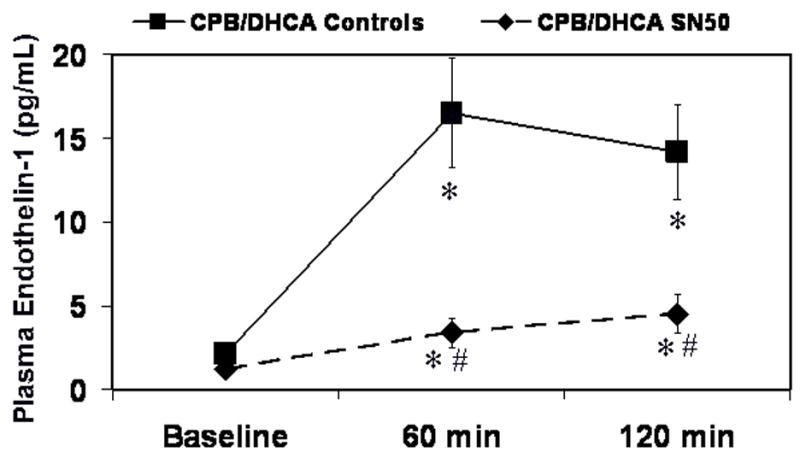

Plasma Endothelin-1 Levels

Plasma endothelin-1 levels increased with CPB/DHCA from 2.1±0.37 pg·mL−1 at baseline to 14.2±5.7 pg·mL−1 at 120 minutes (P=.004, Fig 7). A large portion of the elevation in endothelin-1 levels was alleviated by NF-κB inhibition, but there was still a rise from baseline endothelin-1 levels (1.2±.76 pg·mL−1) at 120 minutes after CPB/DHCA (4.5±2 pg·mL−1, P=.005 vs baseline, P=.003 vs CPB/DHCA controls).

Fig 7.

Plasma endothelin-1 levels in piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus baseline within treatment groups; # P<.05 versus CPB/DHCA controls at the same time point.

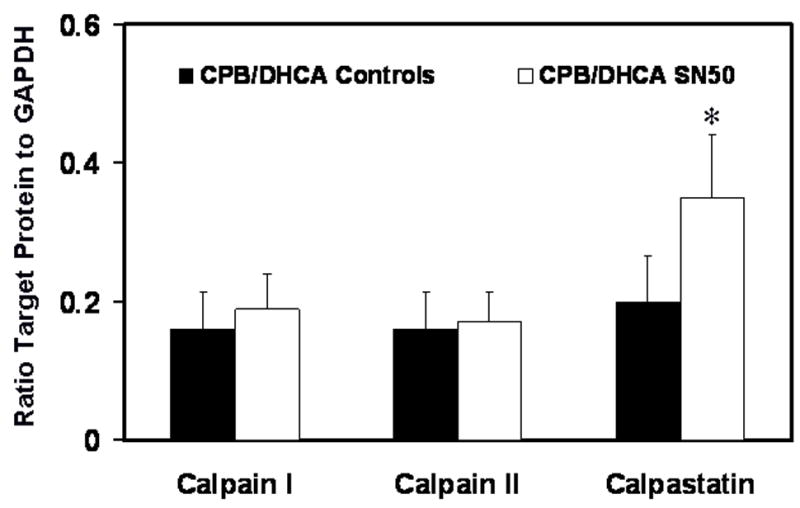

Calpain and Calpastatin Activity and Protein Levels

SN50 treatment did not affect the densitometry ratio of calpain I and II to GAPDH protein levels in LV myocardium at 120 minutes after CPB-DHCA (P>.05, Fig. 8). However, calpastatin protein was higher in SN50-treated animals than in the untreated group (.35±.06 vs .20±.07 densitometry ratio of calpastatin to GAPDH, P=.05).

Fig 8.

Calpain I and II and calpastatin protein levels in the myocardium of the left ventricle from piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus CPB/DHCA controls.

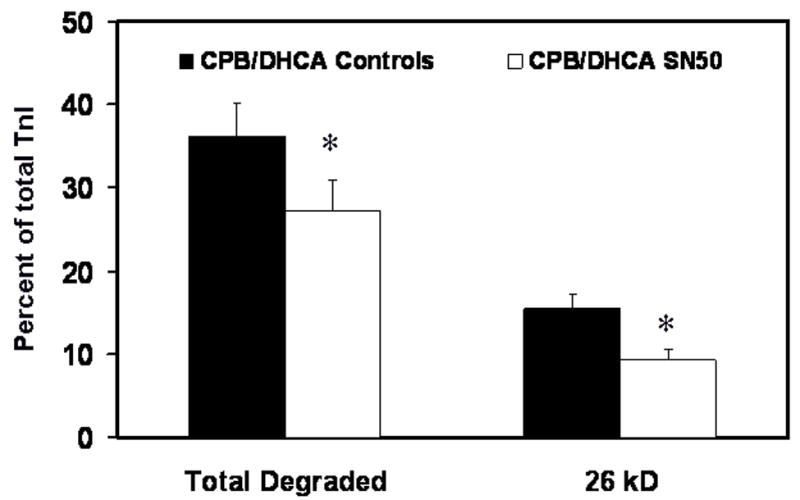

Troponin I Degradation

Total troponin I degradation and the main 26 kD degradation product in the LV myofibrils isolated 120 min after CPB/DHCA were significantly lower in SN50 treated animals than controls (Fig. 9). The TnI detected in all the degradation bands for the CPB/DHCA controls was 36.2±2.4% of the total detected compared with 27.3±3.5% for the SN50-treated animals (P=.007). The major TnI degradation product at 26 kD was 15.5±4.3% of the total TnI for the untreated animals and only 9.3±1.4% in the SN50-treated animals (P=.01).

Fig 9.

Troponin I (TnI) degradation in myofibrils isolated from the left ventricle of piglets subjected to cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (CPB/DHCA) with or without inhibition of NF-κB. *P<.05 versus CPB/DHCA controls.

Discussion

In the early minutes of myocardial reperfusion a sudden influx of calcium activates numerous pathways resulting in myocyte dysfunction and injury, and even myocyte death secondary to contracture (16). Calcium overload associated with ischemia and reperfusion activates calpains and reduces calpastatin levels (17, 18). Until recently, no in vivo studies have examined calpain regulation of the NF-κB pathway during reperfusion of immature myocardium. In prior studies we demonstrated an association between calpain inhibition, maintenance of IκBα protein in the cytosol, and decreased NF-κB activity (3). These changes were associated with reduced markers of inflammation (2) and apoptotic cell injury (19). Having demonstrated an effect of calpain inhibition on NF-κB activation, we attempted to compare the functional recovery seen with calpain inhibition with changes in NF-κB activity. In the current study, the cardiopulmonary functional recovery with NF-κB inhibition was similar to that observed in calpain inhibition studies.

Glucocorticoid treatment, which prevented the breakdown of calpastatin in myocardium after CPB/DHCA (1) and direct administration of a peptide calpain inhibitor (2), maintained IκBα protein levels in the cytosol and reduced NF-κB binding to DNA in the nucleus. With various modes of activation, IκBα underwent serine phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation through a well-characterized proteosomal pathway (20). However, recent studies indicated that two parallel pathways of IκB degradation exist: the proteosomal pathway and a calpain-dependent pathway that degraded IκBα after phosphorylation (21), probably regulated by tyrosine instead of serine phosphorylation (9, 22). In specific cell types, such as IgM+ B cells, IκBα degradation through calpain-regulated mechanisms was more important than the proteosome pathway (8). Tyrosine kinase regulation of NF-κB activation was especially evident during ischemic preconditioning in the heart (23, 24). As neonatal hearts have higher levels of calpain than adults, a possible reliance on calpain-mediated IκB regulation could exist. However the administration of high doses of corticosteroids to patients during CPB remains controversial (25). A number of studies indicate that high dose steroids can result in detrimental postoperative alterations. Therefore the goal would be to target specific therapies to the beneficial steroid pathways that do not activate the broad spectrum of effects associated with steroid administration.

A basal level of NF-κB might be necessary to maintain the pro-survival signal in some cell types, for instance, NF-κBp65−/− mice die at mid-gestation due to severe apoptosis in the liver (26). Stimuli inducing NF-κB above this basal level, however, may overpower the pro-survival signal and result in cell injury or death. Although targeting a specific activity level for NF-κB would be clinically challenging the potential to affect one pathway activating NF-κB, such as the calpain-mediated pathway, while leaving other activators intact, might provide a mechanism to regulate NF-κB downstream genes without ablating basal levels.

Effect of NF-κB inhibition on pulmonary function

These data indicated a significant attenuation of the typical increase in CPB/DHCA-associated PVR by suppressing the elevation in NF-κB activity with SN50. The reduction in PVR was associated with a marked reduction in the elevated levels of endothelin-1 detected in untreated animals undergoing CPB/DHCA. Interestingly, these changes were similar to those seen with calpain inhibition (3). Little is known about the role of calpain in regulation of PVR or pulmonary function. However, endothelin-1 is a potent and important regulator of PVR in the perioperative period. Administration of bosentan, an endothelin-1 receptor antagonist, reduces pulmonary hypertension in a very similar piglet model of hypoxia and reoxygenation on CPB (14). While endothelin-1 production can be regulated through several pathways, NF-κB has a direct role in stimulating endothelin-1 transcription. It was not surprising therefore that NF-κB reduction with SN50 could decrease plasma endothelin-1, resulting in lower PVR after CPB/DHCA. The effect of calpain inhibition on PVR and endothelin-1 might be through regulation of NF-κB, although a direct effect of calpain on endothelin-1 levels cannot be ruled out.

Effect of NF-κB inhibition on cardiac function

The current study demonstrated a significant benefit of SN50 on myocardial function, as well as, clinically relevant signs of cardiac output. Blocking the rise in NF-κB associated with CPB/DHCA resulted in both improved systolic and diastolic function measured by maximum and minimum dP/dt, Tau, and preload recruitable stroke work. Furthermore, the reduction in cardiac dysfunction was associated with improved oxygen delivery and would be considered relevant in the clinical setting. The data are in agreement with prior studies that showed inhibition of NF-κB attenuates inflammation and apoptosis associated with myocardial ischemia and reperfusion (27).

Effect of NF-κB inhibition on markers of myocardial injury

Troponin is a major contractile protein in the mammalian heart that is a target for calpain proteolytic activity. Inhibition of calpain activity prevents TnI degradation in rodent hearts (28, 29) and in this model (1). The current study demonstrated a reduction in both total troponin I degradation products and the major 26 kD degradation product in SN50-treated animals. However, calpain cleavage of TnI was thought to be a direct proteolytic effect and not necessarily related to NF-κB. Nonetheless in this study, NF-κB inhibition resulted in decreased TnI degradation and was associated with preservation of calpastatin levels, indicating a possible regulation of calcium-dependent calpain activity by NF-κB. Reducing calcium influx could modulate cardiomyocyte calpain activity and the calpain-mediated degradation of calpastatin. The higher calpastatin levels with NF-κB inhibition might then be protective of troponin proteins susceptible to calpain degradation. Modalities that preserve intact myofilament proteins may reduce myocardial dysfunction after reperfusion.

NF-κB mediation of calpain activation

There are very limited indications that NF-κB can affect calpain activation, possibly through regulation of calcium influx. Nuclear factor-κB can suppress expression of Cav1.2 calcium channels in smooth muscle cells with kappaB binding sites on the L-type calcium channel gene that prevent the contractile response to acetylcholine (30). In addition, NF-κB binds the promoter of the transient receptor potential channel 1 (TRPC1) gene in endothelial cells, which induces calcium influx after depletion of intracellular calcium stores (31). These mechanisms of NF-κB calcium regulation might provide a link for NF-κB mediation of calpain activity, higher calpastatin levels in the heart, and NF-κB’s reduction in TnI degradation.

Conclusions

The multi-factorial activation of NF-κB alters gene expression not only between cell types, but within the same cells depending on environmental conditions. The dose of SN50 in the current study was chosen for partial, not complete, blockade of NF-κB activity. Potential therapeutics directed at mediating NF-κB-induced gene expression should minimize but not ablate NF-κB activation. Calpain-mediated IκBα degradation may be a potential therapeutic target to reduce detrimental NF-κB-activated responses to ischemia and reperfusion without stimulating cell injury with total blockade.

Acknowledgments

KMM was supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Service Research Award, #5T32-GM-008478-13 and AJC was supported by training grant NIDDK #DK60444-06. This study was supported by NIH grant # 5 R01 HL077653 to JMP and JYD.

Reference List

- 1.Schwartz SM, Duffy JY, Pearl JM, Goins S, Wagner CJ, Nelson DP. Glucocorticoids preserve calpastatin and troponin I during cardiopulmonary bypass in immature pigs. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:91–97. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000065730.79610.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffy JY, Nelson DP, Schwartz SM, et al. Glucocorticoids reduce cardiac dysfunction after cardiopulmonary bypass and circulatory arrest in neonatal piglets. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:28–34. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000102382.92024.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffy JY, Schwartz SM, Lyons JM, et al. Calpain inhibition decreases endothelin-1 levels and pulmonary hypertension after cardiopulmonary bypass with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:623–628. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000156243.44845.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z-Q, Kunimatsu M, Yang J-P, Ozaki Y, Sasaki M, Okamoto T. Proteolytic processing of nuclear factor κB by calpain in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1996;385:109–113. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rupp H. Calcium-dependent activation of cardiac myofibrils. The mechanisms that modulate myofibrillar ATPase and tension and their significance for heart function. Adv Myocardiol. 1982;3:45558–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao WD, Atar D, Liu Y, Perez NG, Murphy AM, Marbán E. Role of troponin I proteolysis in the pathogenesis of stunned myocardium. Circ Res. 1997;80:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Eyk JE, Powers F, Law W, Larue C, Hodges RS, Solaro RJ. Breakdown and release of myofilament proteins during ischemia and ischemia/reperfusion in rat hearts: identification of degradation products and effects on the pCa-force relation. Circ Res. 1998;82:261–271. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyamoto S, Seufzer BJ, Shumway SD. Novel IκBα proteolytic pathway in WEHI231 immature B cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:19–29. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waris G, Livolsi A, Imbert V, Peyron JF, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis c virus NS5A and subgenomic replicons activate NF-κB via tyrosine phosphorylation of IκBα and its degradation by calpain protease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40778–40787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schötzke MN, Potrovita I, Subramaniam S, Prinz S, Schwaninger M. Glutamate activates NF-κB through calpains in neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:3305–3310. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo J, Kamata H, Karin M. IKK/NF-κB signaling: balancing life and death - a new approach to cancer therapy. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2625–2632. doi: 10.1172/JCI26322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levkau B, Scatena M, Giachelli CM, Ross R, Raines EW. Apoptosis overrides survival signals through a caspase-mediated dominant-negative NF-kappaB loop. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:227–233. doi: 10.1038/12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearl JM, Schwartz SM, Nelson DP, et al. Preoperative glucocorticoids decrease pulmonary hypertension in piglets after cardiopulmonary bypass and circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:994–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearl JM, Wellmann SA, McNamara JL, et al. Bosentan prevents hypoxia-reoxygenation-induced pulmonary hypertension and improves pulmonary function. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1714–1722. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00988-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solaro RJ, Pang DC, Briggs FN. The purification of cardiac myofibrils with Triton X-100. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;245:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(71)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piper HM, García-Dorado D, Ovize M. A fresh look at reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;38:291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorimachi Y, Harada K, Saido TC, Ono T, Kawashima S, Yoshida K. Downregulation of calpastatin in rat heart after brief ischemia and reperfusion. J Biochem. 1997;122:743–748. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaitanaki C, Papazafiri P, Beis I. The calpain-calpastatin system and the calcium paradox in the isolated perfused pigeon heart. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2003;13:173–180. doi: 10.1159/000071868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearl JM, Nelson DP, Schwartz SM, et al. Glucocorticoids reduce ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial apoptosis in immature hearts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:830–837. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03843-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garg A, Aggarwal BB. Nuclear transcription factor-kappaB as a target for cancer drug development. Leukemia. 2002;16:1053–1068. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Y, Weinman S, Boldogh I, Walker RK, Brasier AR. Tumor necrosis factor-α-inducible IκBα proteolysis mediated by cytosolic m-calpain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:787–791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takada Y, Mukhopadhyay A, Kundu GC, Mahabeleshwar GH, Singh S, Aggarwal BB. Hydrogen peroxide activates NF-κB through tyrosine phosphorylation of IκBα and serine phosphorylation of p65. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24233–24241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valhaus C, Schulz R, Post H, Rose J, Heusch G. Prevention of ischemic preconditioning only by combined inhibition of protein kinase C and protein tyrosine kinase in pigs. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:197–209. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Ping P, Vondriska TM, et al. Cardioprotection involves activation of NF-κB via PKC-dependent tyrosine and serine phosphorylation of IκB-α. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1753–1758. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00416.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaney MA. Corticosteroids and cardiopulmonary bypass. A review of clinical investigations. Chest. 2002;121:921–931. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking RelA component of NF-κB. Nature. 1995;376:167–169. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh CH, Chen TP, Wu YC, Lin YM, Jin Lin P. Inhibition of NFkappaB activation with curcumin attenuates plasma inflammatory cytokine surge and cardiomyocyte apoptosis following cardiac ischemia/reperfusion. J Surg Res. 2005;125:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Lisa F, De Tullio R, Salamino F, Barbato R, Melloni E, Siliprandi N. Specific degradation of troponin T and I by mu-calpain and its modulation by substrate phosphorylation. Biochem J. 1995;308:57–61. doi: 10.1042/bj3080057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kositprapa C, Zhang B, Berger S, Canty JM, Jr, Lee TC. Calpain-mediated proteolytic cleavage of troponin I induced by hypoxia or metabolic inhibition in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;214:47–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1007160702275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi XZ, Pazdrak K, Saada N, Dai B, Palade P, Sarna SK. Negative transcriptional regulation of human colonic smooth muscle Cav1.2 channels by p50 and p65 subunits of nuclear factor-kappaB. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1518–1532. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paria BC, Bair AM, Xue J, Yu Y, Malik AB, Tiruppathi C. Ca2+ influx induced by protease-activated receptor-1 activates a feed-forward mechanism of TRPC1 expression via nuclear factor-κB activation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20715–20727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]