Summary

Heme biosynthesis consists of a series of eight enzymatic reactions that originate in mitochondria and continue in the cytosol before returning to mitochondria. Although these core enzymes are well studied, additional mitochondrial transporters and regulatory factors are predicted to be required. To discover such unknown components, we utilized a large-scale computational screen to identify mitochondrial proteins whose transcripts consistently co-express with the core machinery of heme biosynthesis. We identified SLC25A39, SLC22A4 and TMEM14C, which are putative mitochondrial transporters, as well as C1orf69 and ISCA1, which are iron-sulfur cluster proteins. Targeted knockdowns of all five genes in zebrafish resulted in profound anemia without impacting erythroid lineage specification. Moreover, silencing of Slc25a39 in murine erythroleukemia cells impaired iron incorporation into protoporphyrin IX, and vertebrate Slc25a39 complemented an iron homeostasis defect in the orthologous yeast mtm1Δ deletion mutant. Our results advance the molecular understanding of heme biosynthesis and offer promising candidate genes for inherited anemias.

Introduction

Biosynthesis of heme is a tightly orchestrated process that occurs in all cells (Ponka, 1997). In most eukaryotes heme synthesis (Figure 1A) is initiated in the mitochondrion by δ-aminolevulenic acid synthase (ALAS), which catalyzes the reaction between succinyl-CoA and glycine to form δ-aminolevulenic acid (ALA). ALA is exported to the cytosol, where it is converted through a series of reactions to coproporphyrinogen III. This molecule crosses the outer mitochondrial membrane, is oxidized by the CPOX enzyme in the intermembrane space, and subsequently imported back into the mitochondrial matrix and further oxidized to protoporphyrin IX (PPIX). Heme synthesis is completed by the incorporation of ferrous iron into PPIX by ferrochelatase (FECH). While these eight core enzymes have been extensively characterized, the means by which ALA and porphyrin intermediates enter the mitochondrion, how heme matures in the mitochondrion, and how it is then exported to the cytosol are largely unknown.

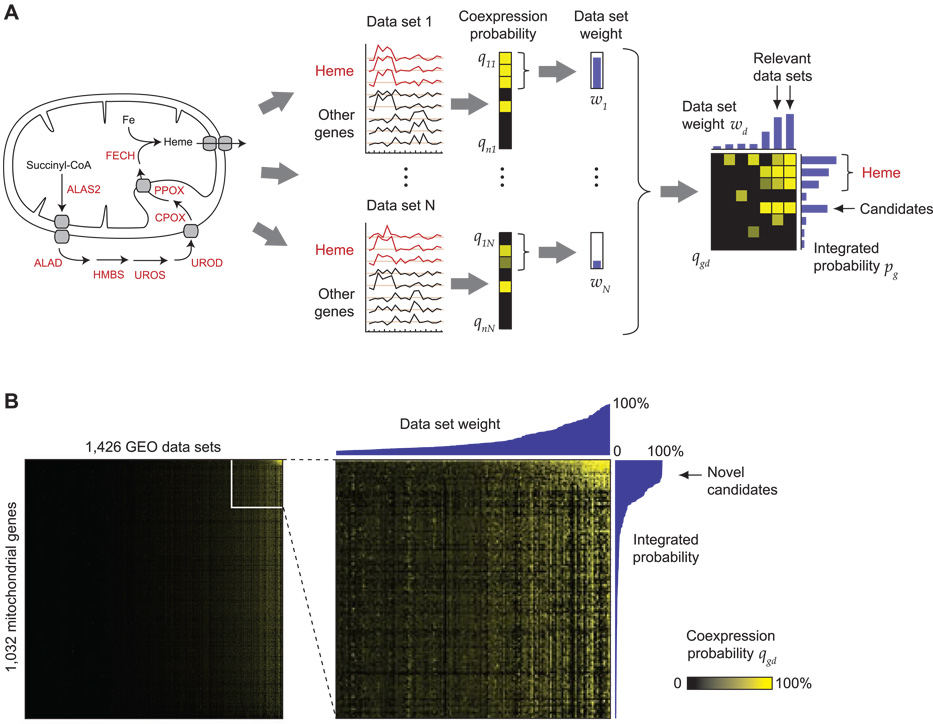

Figure 1.

Identifying novel candidate genes for heme biosynthesis using expression screening. (A) The eight known enzymes of heme biosynthesis pathway (left) defines the query pathway. Using a rank-based statistic, each gene g is assigned a probability of coexpression qgd in each microarray data set d (black/yellow columns). Data sets where the heme biosynthesis enzymes are themselves tightly coexpressed are assigned larger weights wd (blue vertical bars), which are then used to integrate the coexpression information from all data sets (black/yellow matrix, right) into a final probability pg (blue horizontal bars). (B) The coexpression matrix for the 1,426 data sets used in this study (columns), over 1,032 mitochondrial genes (rows). Yellow color indicates strong coexpression. Right, a magnified portion of this matrix, with data set weights (top) and integrated probabilities (right).

Heme serves as a prosthetic group in many enzymes that are involved in important processes such as electron transport, apoptosis, detoxification, protection against oxygen radicals, nitrogen monoxide synthesis, and oxygen transport (Ajioka et al., 2006). The latter process places a special demand for heme synthesis in the developing erythron, which needs to generate vast amounts of the oxygen carrier protein hemoglobin. In mammals, the regulation of heme synthesis differs between erythroid and non-erythroid cells. In non-erythroid cells, heme itself plays a key regulatory role and represses transcription through feedback mechanisms (May et al., 1995). In red blood cells, iron availability is the dominant factor (Ponka, 1997). Erythroid and non-erythroid cells also express distinct isoforms of the core heme biosynthesis enzymes. For example, the ubiquitous form of ALAS is encoded by ALAS1, while a separate gene ALAS2 encodes the erythroid-specific enzyme. These different modes of regulation probably reflect the extraordinary need for mitochondrial iron assimilation and heme synthesis during erythroid maturation.

In recent years several new genes involved in heme synthesis have been discovered. Genetic screening in zebrafish revealed that Mitoferrin-1 (SLC25A37), a vertebrate homolog of the yeast mitochondrial iron importers MRS3/MRS4, plays an important role in heme metabolism in erythroid cells (Shaw et al., 2006a). A more ubiquitously expressed SLC25A37 paralog, SLC25A28, is important for heme synthesis in non-erythroid cells (Paradkar et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2006a). Unbiased functional screening methods have also, rather surprisingly, implicated genes involved in iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster synthesis as important for heme production. In yeast, deletions of several genes important for mitochondrial Fe-S cluster assembly negatively affect heme synthesis (Lange et al., 2004). Deletion of the mitochondrial ATP binding cassette transporter ABCB7, which is an essential component of the Fe-S cluster export machinery, results in reduced heme levels in mouse erythrocytes (Pondarre et al., 2007). A study in the zebrafish mutant shiraz revealed that a mutation in the Fe-S cluster assembly gene glutaredoxin 5 (GLRX5) affects heme biosynthesis through the cytosolic iron responsive protein 1 (IRP1) (Wingert et al., 2005). Under low iron conditions, diminished Fe-S cluster assembly induces IRP1 to lose its Fe-S cluster, resulting in binding to iron responsive elements (IRE) and subsequent posttranslational regulation of genes involved in iron and heme homeostasis (Muckenthaler et al., 2008; Rouault, 2006). Wingert et al. showed that impaired heme production in the zebrafish shiraz mutant was due to the constitutive repression of ALAS2 by IRP1, thereby inhibiting ALAS2 translation and subsequent production of heme. This study confirms the intimate relation between Fe-S cluster synthesis and heme biosynthesis (Lill and Mühlenhoff, 2008; Muckenthaler et al., 2008; Rouault, 2006).

Several human diseases have been linked to genes involved in heme biosynthesis. Mutations in any of the eight core enzymes except ALAS (Figure 1A) lead to various forms of porphyria (Sassa, 2006). Defects in ALAS2, ABCB7, GLRX5 and SLC25A38 are each associated with different forms of sideroblastic anemias (Allikmets et al., 1999; Camaschella et al., 2007; Cotter et al., 1992; Guernsey et al., 2009), which are characterized by mitochondrial iron overload and impaired heme synthesis. Aberrant splicing of SLC25A37 (Shaw et al., 2006b), deletion of IRP2 (Cooperman et al., 2005), and c-terminal deletions in ALAS2 (Whatley et al., 2008) are associated with a variant form of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Other human disorders involving defects in iron homeostasis and heme metabolism exist, and identifying the genes responsible is vital to understanding their nature and providing new ways for treatment.

Aiming to systematically identify new components of the heme biosynthesis pathway, we applied a computational screening algorithm that searches a large collection of microarray data sets for genes that are consistently and specifically co-expressed with the eight heme biosynthesis genes, depicted in Figure 1A. Applying this computational screening technique to a compendium of 1100 mitochondrial genes yielded a collection of strong candidate genes. We used zebrafish as an in vivo vertebrate model system to test five high-scoring candidates. We found that all five genes are required for proper synthesis of hemoglobin, indicating high specificity of our computational predictions. We chose to study one candidate, the solute carrier SLC25A39, in greater detail in mouse and yeast, and our results support a role for this gene in maintaining mitochondrial iron homeostasis and regulating heme levels.

Results

Using microarray technology it is possible to measure correlation of expression patterns on a whole-genome scale (Quackenbush, 2001). However, expression patterns may be correlated in a particular experiment for trivial reasons such as stress responses or adaptation to cell culture conditions (Cahan et al., 2007), so expression correlation does not in itself imply close functional relationship. To address this problem and improve specificity, we reasoned that genes co-expressed consistently across many independent data sets, which interrogate different experimental conditions, are more likely to be functionally related. Based on this principle, we developed a computational technique we call expression screening that integrates information from thousands of microarray data sets to discover genes that are specifically co-expressed with a given query pathway, such as mitochondrial heme biosynthesis (Figure 1A). We assembled a collection of 1,426 mouse and human Affymetrix microarray datasets (approx. 35,000 microarrays) representing a wide range of experimental conditions (see Methods). For each data set in this collection, expression screening scores every gene for co-expression with the query pathway using a rank-based statistic. Importantly, we also compute a measure of the intra-correlation of the query pathway in each data set, reflecting the extent to which the query pathway is transcriptionally regulated. Finally, we integrate the co-expression information from all data sets weighted by the query pathway intra-correlation. This weighting scheme allows the most “relevant” data sets to contribute the most to the final result, and also permits identification of biological contexts where the co-expression occurs.

A Large-Scale Computational Screen Reveals Genes Essential for Heme Biosynthesis

We applied expression screening to the eight well-characterized heme biosynthesis enzymes. Since proteins involved in heme biosynthesis are likely mitochondrial, we chose to limit our screen to a high-quality inventory of ~1,100 nuclear genes encoding the mitochondrial proteome (Pagliarini et al., 2008). A fraction of these showed strong co-expression with the heme enzymes in a small number of data sets (Figure 1B). Among the top five co-expressed genes identified by our screen, not counting the heme biosynthesis enzymes themselves, four had previously been implicated in heme biosynthesis (Table 1). These were ABCB6, the only known transporter for a porphyrin intermediate (Krishnamurthy et al., 2006); SLC25A37, a mitochondrial solute carrier that supplies iron to mitochondria for heme and Fe/S biogenesis (Shaw et al., 2006a); ABCB10, which is induced by GATA1 during erythroid differentiation and enhances hemoglobinization (Shirihai et al., 2000); and GLRX5, which regulates heme synthesis through a feedback loop involving IRP1 (Wingert et al., 2005). At somewhat lower confidence levels we found genes up-regulated in red blood cells, reflecting the fact that erythropoiesis drives most of the co-expression signal for this pathway.

Table 1.

Top 30 co-expressed mitochondrial genes discovered by expression screening. Query, genes used as input for screening; Heme, genes known to be required for functional heme biosynthesis; Fe-S, genes involved in iron-sulfur cluster assembly; Follow-up, candidates selected for further study.

| Symbol | Description | Probability | Target | Heme | Fe-S | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UROD | uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | 1.00 | x | x | ||

| HMBS | hydroxymethylbilane synthase | 1.00 | x | x | ||

| FECH | ferrochelatase (protoporphyria) | 1.00 | x | x | ||

| ALAD | aminolevulinate, delta-, dehydratase | 1.00 | x | x | ||

| GLRX5 | glutaredoxin 5 | 1.00 | x | x | ||

| PPOX | protoporphyrinogen oxidase | 1.00 | x | x | ||

| ALAS2 | aminolevulinate, delta-, synthase 2 | 1.00 | x | x | ||

| ABCB6 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 6 | 1.00 | x | |||

| UROS | uroporphyrinogen III synthase (congenital erythropoietic porphyria) | 0.99 | x | x | ||

| CPOX | coproporphyrinogen oxidase | 0.99 | x | x | ||

| SLC25A37 | solute carrier family 25, member 37 | 0.99 | x | |||

| PRDX2 | peroxiredoxin 2 | 0.99 | ||||

| ABCB10 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 10 | 0.99 | x | |||

| HAGH | hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase | 0.98 | ||||

| TMEM14C | transmembrane protein 14C | 0.97 | x | |||

| SLC25A39 | solute carrier family 25, member 39 | 0.96 | x | |||

| TXNRD2 | thioredoxin reductase 2 | 0.96 | ||||

| NT5C3 | 5′-nucleotidase, cytosolic III | 0.93 | ||||

| NCOA4 | nuclear receptor coactivator 4 | 0.85 | ||||

| SLC22A4 | solute carrier family 22 (organic cation transporter), member 4 | 0.81 | x | |||

| UCP2 | uncoupling protein 2 (mitochondrial, proton carrier) | 0.80 | ||||

| ISCA1 | iron-sulfur cluster assembly 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 0.71 | x | x | ||

| C10orf58 | chromosome 10 open reading frame 58 | 0.68 | ||||

| HK1 | hexokinase 1 | 0.68 | ||||

| ISCA2 | iron-sulfur cluster assembly 2 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 0.62 | x | |||

| MCART1 | mitochondrial carrier triple repeat 1 | 0.62 | ||||

| FAHD1 | fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase domain containing 1 | 0.59 | ||||

| COX6B2 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIb polypeptide 2 (testis) | 0.55 | ||||

| ATPIF1 | ATPase inhibitory factor 1 | 0.49 | ||||

| C1orf69 | RIKEN cDNA A230051G13 gene | 0.45 | x | x |

Several top-scoring candidates had not previously been implicated in heme biosynthesis or mitochondrial iron homeostasis. Because of the membrane transport events involved in heme synthesis (Figure 1A), we were particularly interested in orphan solute transporters. For follow-up studies, we selected three genes we considered possible transporters: TMEM14C, a small transmembrane protein, and SLC25A39 and SLC22A4, members of the solute carrier family. We also selected ISCA1 (yeast ISA1) and C1orf69 (yeast IBA57), which are known to participate in the maturation of Fe-S clusters essential for the activity of a specific subset of mitochondria proteins (Gelling et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2005), but have not been directly implicated in heme biosynthesis.

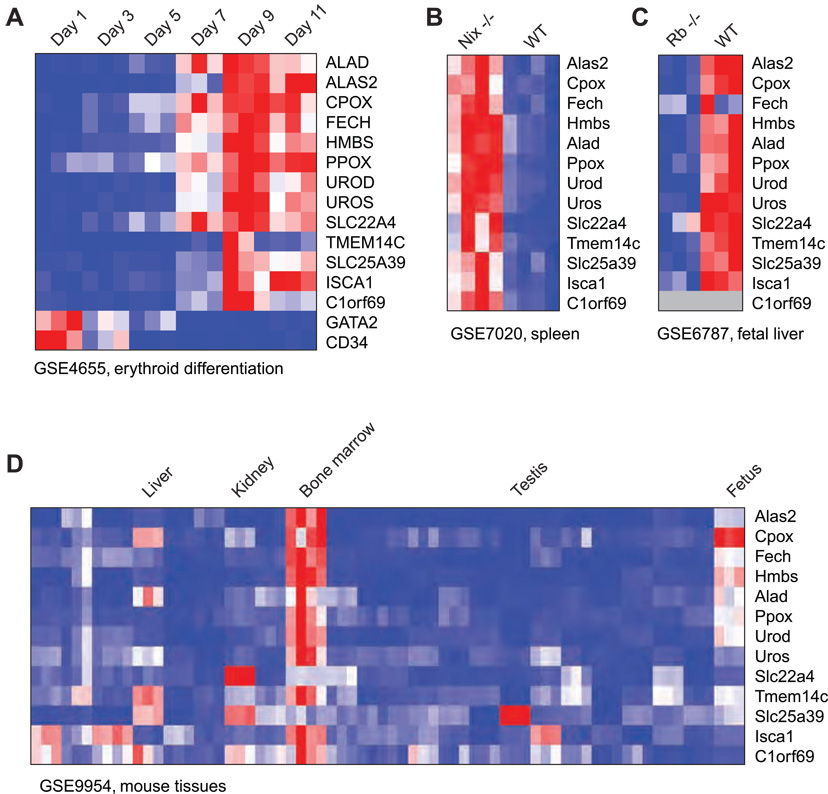

In addition to predicting new components of the query pathway, expression screening also identifies the data sets where co-expression occurs, thus suggesting biological contexts where the pathway is active. For heme biosynthesis, the highest-scoring data set is a time-course analysis of erythrocytes differentiating in vitro from primary human hematopoietic progenitor cells (Keller et al., 2006) (Figure 2A). Here, the eight heme biosynthesis enzymes are strongly induced at day 9, and at this time point the novel candidates also reach peak expression, suggesting that they function during late erythrocyte differentiation, concurrent with hemoglobin synthesis. In contrast, early hematopoietic markers such as CD34 and GATA2 are expressed at early time points in this data set. In another high-scoring data set, we found up-regulation of the candidates in Nix−/− mouse spleens (Figure 2B), which exhibit increased numbers of erythrocyte precursors due to a defect in mitochondria clearance during terminal erythrocyte differentiation (Diwan et al., 2007; Sandoval et al., 2008). Conversely, all candidates were down-regulated when erythrocyte differentiation is abolished in Rb−/− fetal liver (Figure 2C) (Spike et al., 2007). Several multiple-tissue data sets were also high-scoring due to strong expression in erythropoietic tissues such as bone marrow (Figure 2D). These contexts all reflect red blood cell biology, as expected. However, we also found regulation of the heme pathway in activated white blood cells and in some lymphomas, suggesting a previously unrecognized importance of heme biosynthesis in these contexts (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2.

Microarray datasets where the heme biosynthetic pathway is regulated. (A) Time-series gene expression of heme biosynthesis enzymes and five selected candidates (see text) during erythroid differentiation. (B) Gene expression in Nix−/− and wild-type (WT) mouse spleen. (C) Gene expression in Rb−/− and wild-type (WT) mouse fetal liver. (D) Gene expression in a panel of mouse tissues. Red color indicates high expression; blue, low expression; gray color, missing values. GSE, NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus accession number.

In Situ Expression Analysis of Five Candidate Genes in Zebrafish Embryos

To investigate the biological role of the five selected genes in red blood cell development, we used the zebrafish (Danio rerio), which serves as an excellent in vivo model system for studying hematological disorders (Shafizadeh and Paw, 2004). To identify zebrafish orthologs of the five candidates, we used reciprocal protein-level BLAST. We were able to predict clear zebrafish orthologs for SLC25A39, TMEM14C, C1orf69 and ISCA1. However, mammalian SLC22A4 exhibited close sequence similarity with zebrafish slc22a4 and slc22a5, and a multiple alignment of these genes between mouse, human and fish did not resolve the orthology (Supplementary Figure S1). We therefore included both possible orthologs for functional follow-up.

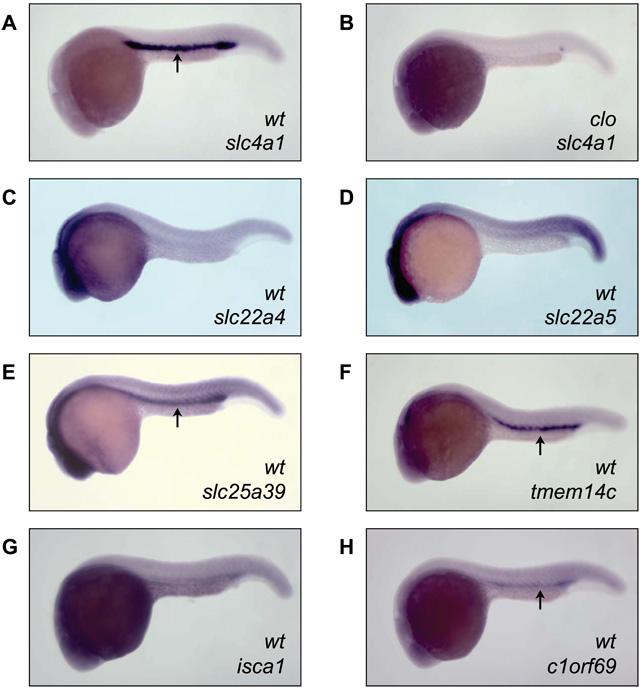

Whole mount in situ hybridization of zebrafish embryos at 24 hour postfertilizaton (hpf) showed clear localization of mRNA for slc25a39, tmem14c and c1orf69 (Figure 3) to the intermediate cell mass (ICM), the functional equivalent of mammalian yolk sac blood islands. Transcripts for isca1, slc22a4 and slc22a5 did not show clear tissue-restricted expression in the developing zebrafish embryo (Figure 3); however, real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis indicated very low levels of slc22a4 and slc22a5 mRNA in 24 hpf embryos (data not shown), possibly explaining absent staining in the ICM by the less sensitive in situ hybridization method. Real-time qRT-PCR analysis of isca1 mRNA, on the other hand, showed high overall expression at 24 hpf (data not shown), indicating that isca1 is not specific to the ICM. To clearly delineate the ICM, slc4a1, an erythroid-specific cytoskeletal protein (Paw et al., 2003) was included in the analysis (Figure 3A). We did not detect staining for any of these genes in zebrafish cloche (clo) mutants, which lack hematopoietic and vascular progenitors (Stainier et al., 1995), indicating specificity of the in situ hybridization results (slc4a1, Figure 3B; remaining genes, data not shown).

Figure 3.

Expression of candidate genes in zebrafish blood islands. Whole embryo in situ hybridization was performed on embryos at 24hpf. (A) Slc4a1 was used as control to delineate the intermediate cell mass (ICM, indicated by arrows). (B) Cloche (clo) embryos were used to show specificity of the hybridizations. (C–G) Candidates identified in this study.

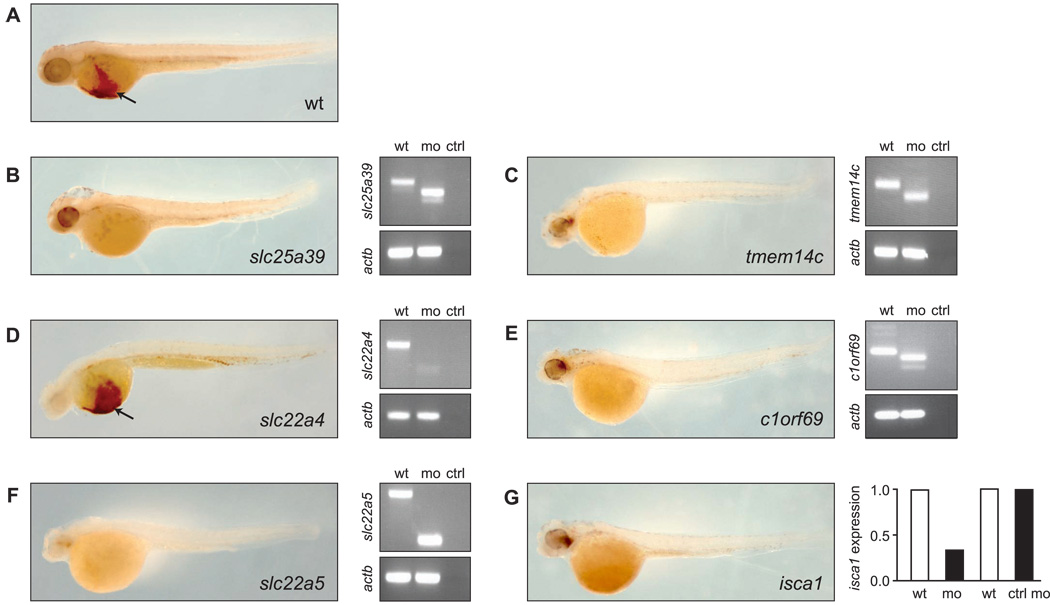

Knockdown in Zebrafish Results in Profound Anemia without Affecting Erythroid Specification

To evaluate a possible function in erythropoiesis, we disrupted mRNA expression of each candidate gene in developing zebrafish embryos using splice-blocking morpholino oligomers (Summerton and Weller, 1997). These knockdowns resulted in profound anemia, as indicated by the lack of hemoglobinized cells after staining the embryos with o-dianisidine (Figure 4), for all candidates except slc22a4 (Figure 4D). Even at very high concentration, the slc22a4 targeting morpholino did not induce anemia. Therefore, the anemia resulting from slc22a5 knockdown suggests that this gene, and not slc22a4, is the functional zebrafish ortholog of mammalian SLC22A4. A quantitative enumeration of the anemia in control and morphant embryos for each silenced gene is displayed in supplementary Figure S2. With the exception of anemia, the morphant embryos generally did not exhibit other gross developmental abnormalities at the chosen doses of morpholino. RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from the morphant embryos showed alternate mRNA species (eventually leading to nonsense mediated mRNA decay) being generated for slc25a39, slc22a4, slc22a5, tmem14c and c1orf69, but not for WT uninjected embryos (Figure 4B–F), demonstrating accurate gene targeting of the respective morpholinos. Off-target effects were excluded by normal RT-PCR products for the β-actin (actb) control. Because we could not detect alternate mRNA species in embryos injected with the isca1-targeted morpholino, we measured isca1 mRNA expression by real-time qRT-PCR. Embryos injected with the isca1 morpholino showed a 3-fold downregulation compared to WT uninjected embryos (Figure 4G). Injection of a non-specific standard control morpholino did not affect isca1 mRNA expression levels (Figure 4G).

Figure 4.

Morpholino knockdown of candidate genes in zebrafish results in profound anemia. WT zebrafish embryos were injected at the 1-cell stage with the respective morpholinos and stained at 48hpf with o-dianisidine to detect hemoglobinized cells. (A) Uninjected (wt) embryos show normal hemoglobinization as indicated by dark-brown staining on the yolk sac (arrow). (B–G) Morpholino-injected embryos. Accurate morpholino gene targeting was verified by RT-PCR (slc25a39, slc22a4, slc22a5, tmem14c, and c1orf69) or real-time quantitative RT-PCR (isca1) on cDNA from uninjected (wt) or morpholino-injected (mo) embryos. β-actin (actb) was used as a control for off-target effects in the RT-PCR. For RT-PCR, (ctrl) indicates no cDNA template control. For real-time quantitative RT-PCR, (ctrl mo) indicates embryos injected with a standard control morpholino.

To show that the anemic phenotype observed by morpholino knockdown is not merely due to a lack of erythrocyte progenitors and is erythroid lineage specific, we stained morphant embryos for the erythroid lineage specific gene αE3-globin (hbae3) at 24 and 48 hpf, and for the myeloid lineage specific gene myeloperoxidase (mpo) (Bennett et al., 2001) at 48 hpf by whole mount in situ hybridization. The results indicate that expression of mpo and hbae3 at 24 hpf was overall comparable to wildtype embryos, indicating that initial specification of erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis are not perturbed by deficiency of our candidate genes (Supplementary Figure S3). A slight decrease in hbae3 levels was observed at 48 hpf for all candidates except slc22a4. This probably reflects reduced viability of a number of erythroid cells, an expected consequence of silencing genes that perform important functions in erythroid cells. In summary, the loss of heme staining seen in Figure 4 is not due to defective erythroid lineage specification, and knockdowns do not affect other hematopoietic lineages such as myeloid cells, implicating erythroid-specific roles for the candidates.

Slc25a39 is Highly Expressed in Mouse Hematopoietic Tissues

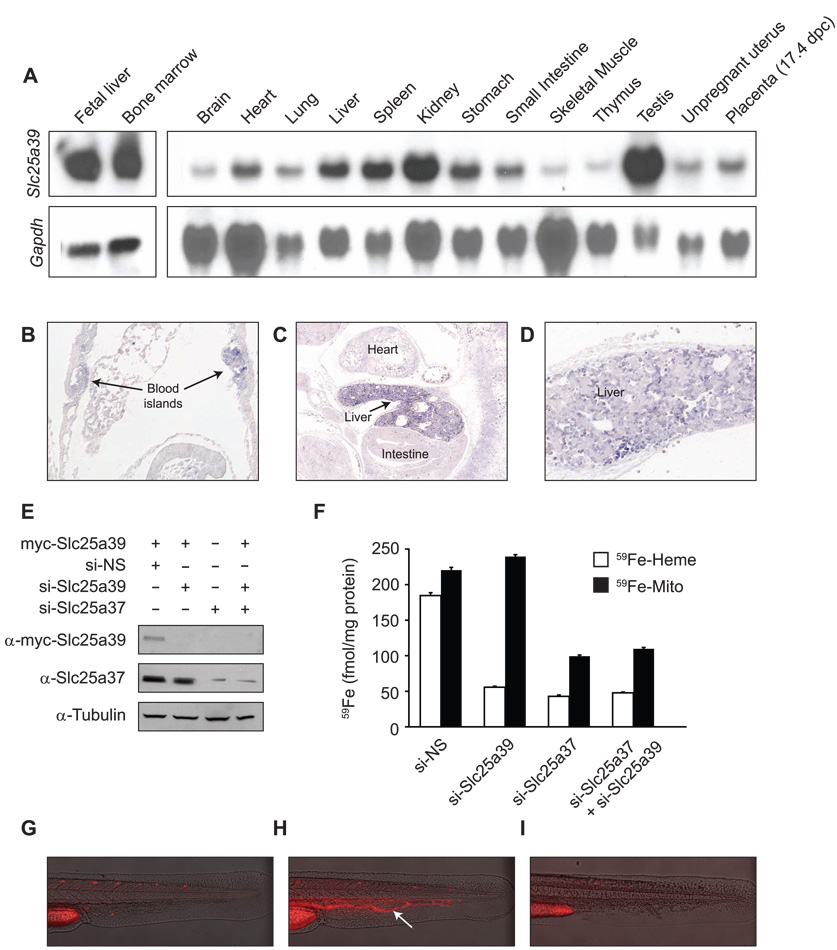

We chose to further investigate the function of SLC25A39 because of its sequence homology to the S. cerevisiae gene MTM1, which has previously been implicated in iron homeostasis (Yang et al., 2006). To characterize its function in mammals, we first investigated the tissue distribution and developmental expression of murine Slc25a39. Northern blot analysis revealed abundant Slc25a39 mRNA expression in the hematopoietic organs fetal liver, adult bone marrow and spleen (Figure 5A). Significant mRNA expression was also observed in the testis and kidneys (Figure 5A). This expression profile is largely consistent with that observed in microarray data (Figure 2D). We also found that Slc25a39 is highly expressed in primitive mouse erythroblasts that fill yolk sac blood islands at early somite pair stages (Figure 5B), and in fetal liver (mid-gestation at day E12.5), the site of definitive erythropoiesis (Figure 5C and D). This expression pattern is concordant with slc25a39 staining in the zebrafish ICM, and suggests that this gene functions in both primitive and definitive erythropoiesis in mammals.

Figure 5.

Mouse Slc25a39 is expressed in hematopoietic tissues and is important for heme biosynthesis. (A) Mouse tissue northern blot analysis of Slc25a39 expression. (B) Mouse Slc25a39 transcripts are localized to blood islands of the yolk sac at early somite stages (E8.5, arrows). (C) and (D) Slc25a39 transcripts accumulate most abundantly in the liver where expression is heterogeneous (E12.5). (E) and (F) MEL cells were differentiated for two days in media containing 1.5% DMSO prior to (E) transient transfection with myc-tagged Slc25a39 or (F) silencing of Slc25a39 (si-Slc25a39) and/or Slc25a37 (si-Slc25a37) using siRNA oligos. Assays were performed after two additional days of differentiation. si-NS indicates silencing using non-specific control oligos. (E) Representative western blot using anti-myc (α-myc-Slc25a39) and anti-Slc25a37 antibodies. Equal loading was verified by anti-tubulin. (F) MEL cells were metabolically labeled with 59Fe conjugated to transferrin, and total mitochondrial iron (59Fe-Mito) and iron in heme (59Fe-Heme) were determined. Results shown are from two independent experiments assayed in duplicate; error bars denote standard deviation. (G) (H) and (I) Representative photos of (G) an uninjected, wild-type control zebrafish embryo, (H) a zebrafish embryo injected with a ferrochelatase-specific morpholino, or (H) with a slc25a39-specific morpholino (I). Arrow indicates porphyric red blood cells in circulation.

Slc25a39 is Required for Heme Synthesis But Silencing Does Not Cause Porphyria

The reduced number of heme-positive cells seen in zebrafish slc25a39 knockdowns could be caused by a defect in mitochondrial iron availability. To address this issue and investigate the biochemical role of Slc25a39 in more detail, we labeled differentiating wild-type and Slc25a39 siRNA-treated mouse erythroleukemia (MEL) cells with 59Fe-saturated transferrin, and assayed for 59Fe incorporation into heme. We confirmed effective silencing of Slc25a39 at the protein level using western analysis (Figure 5E). Wild-type cells treated with non-specific siRNA oligos efficiently incorporated 59Fe into heme; however, Slc25a39 silenced cells showed a 4-fold reduction in 59Fe labeled heme, while total mitochondrial 59Fe remained unaffected, thus excluding its function as a mitochondrial iron importer (Figure 5F). As a positive control, we also performed siRNA knockdown of the iron transporter Slc25a37 (Shaw et al., 2006a), which resulted in marked reduction of total mitochondrial 59Fe as well as heme incorporation of 59Fe (Figure 5F). Simultaneous silencing of Slc25a39 and Slc25a37 did not affect mitochondrial iron content or heme formation more than silencing Slc25a37 alone, indicating that Slc25a37 is epistatic to Slc25a39 for mitochondrial iron import. These data show that Slc25a39 is essential for heme biosynthesis in mammals.

To further delineate the role of SLC25A39 in heme biosynthesis, we asked whether its loss in zebrafish embryos causes a porphyric phenotype. Embryos injected with a morpoholino targeting ferrochelatase clearly exhibited circulating, porphyric red blood cells (Figure 5H), but wildtype embryos and embryos injected with a morpolino targeting slc25a39 did not (Figure 5G,I). Because defects in any of the terminal steps of heme biosynthesis cause accumulation of porphyrin intermediates, this result suggests that SLC25A39 is involved in the early steps of heme synthesis or in the regulation of ALA synthase function.

Vertebrate SLC25A39 Complements Mitochondrial Iron Homeostasis Defects in the Yeast mtm1Δ Mutant

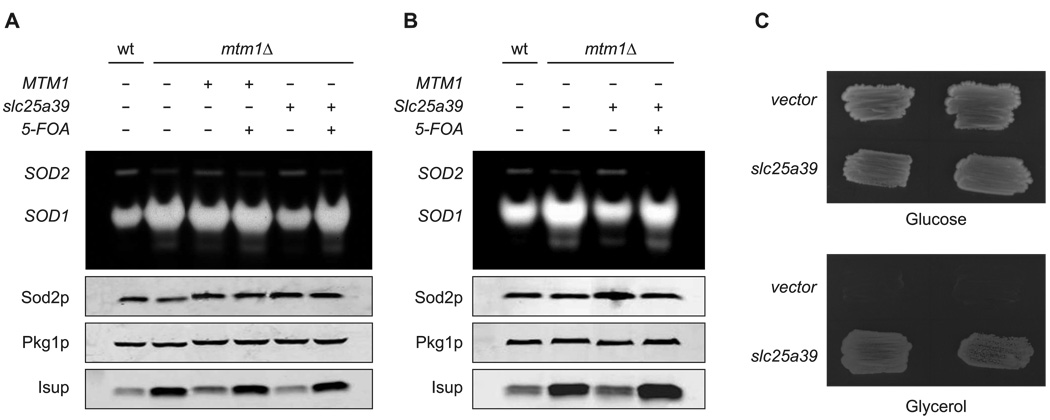

SLC25A39 has clear sequence homology to the S. cerevisiae gene MTM1, for which a deletion strain mtm1Δ has been characterized that exhibits altered iron homeostasis. Loss of MTM1 in yeast alters mitochondrial iron bioavailability such that iron gains access to the catalytic site of manganese superoxide dismutase 2 (Sod2p), thereby inactivating the enzyme (Yang et al., 2006). MTM1 also genetically interacts with the yeast mitochondrial iron importers MRS3 and MRS4, which are orthologs of the human SLC25A37 (Yang et al., 2006). In addition, mtm1Δ mutants exhibit loss of mitochondrial DNA, elevations in Cu/Zn Sod1p activity and an increased level of the mitochondrial Isu1p/Isu2p proteins needed for Fe-S cluster biogenesis (Luk et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2006; A.N. and V.C.C., unpublished data). We expressed zebrafish slc25a39 or mouse Slc25a39 in yeast mtm1Δ mutants, and found that these genes complement low Sod2p and high Sod1p activity as well as the elevated protein levels of Isu1/2 (Figure 6A, B). This complementation was reversed upon subsequent shedding of the plasmid-derived clones with 5-FOA treatment, showing specificity of the assay (Figure 6A, B). We also observed that expression of zebrafish slc25a39 protected against loss of mitochondrial DNA (and concomitant loss of genes important for mitochondrial respiration) upon subsequent deletion of MTM1, as shown by a growth assay on non-fermentable carbon sources (Figure 6C). We conclude that SLC25A39 is the functional vertebrate ortholog of yeast MTM1, supporting an important role for this gene in iron homeostasis.

Figure 6.

Vertebrate SLC25A39 is the ortholog of yeast MTM1 and is involved in mitochondrial iron homeostasis. (A) and (B) mtm1Δ strains were transformed with URA3 based plasmids for expressing (A and B) S. cerevisiae MTM1, (A) zebrafish slc25a39, or (B) mouse Slc25a39. 5-FOA indicates transformants induced to shed the plasmids by growth on 5-fluoroorotic acid. Whole cell lysates of the transformants, 5-FOA derivatives and the parental WT and mtm1Δ cells were subjected to (top) native gel electrophoresis and NBT staining for SOD (SOD2 and SOD1) activity, and (bottom) to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for Sod2p, Pgk1 (loading control) and Isup (sum of Isu1p and Isu2p). (C) WT strain transformed with either empty pRS426-ADH vector or zebrafish slc25A39 was subjected to MTM1 deletion and tested for mitochondrial DNA function by growth on fermentable (glucose) versus non-fermentable (glycerol) carbon sources. Results shown represent two independent colonies.

Discussion

Expression screening (Figure 1) is based on the simple principle that genes exhibiting a consistent correlation of mRNA levels across multiple experiments are more likely to be functionally related. We applied this method to the heme biosynthesis pathway and, as proof-of-principle, recovered four genes recently implicated in heme biosynthesis (GLRX5, ABCB10, ABCB6, and SLC25A37) among the top five novel predictions. This indicates high specificity of our expression screening predictions. In addition, a number of genes previously not associated with heme biosynthesis and mitochondrial iron homeostasis were identified. In some cases, their function was completely unknown prior to this study, while others, such as ISCA1, have been studied intensively but have not been linked to heme synthesis before. Remarkably, all five genes selected for follow-up studies resulted in an anemic phenotype when silenced in zebrafish embryos. We chose to further focus our efforts on characterizing SLC25A39, and our data support an important role for this mitochondrial solute carrier in mammalian heme synthesis. These results warrant further studies of the remaining high-scoring candidates (Table 1).

Not all genes that showed strong co-expression in the screen are likely to be directly involved in heme biosynthesis: some are presumably merely red blood cell-specific, which is reasonable given that our screen was largely driven by erythrocyte gene expression. In this category we find hexokinase 1 (HK1), which catalyzes the initial step in erythrocyte glycolysis; and glyoxalase II (HAGH), which is involved in synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione. We also detected several proteins thought to participate in erythrocyte oxidant defense, including PRDX2 (Low et al., 2007) and TXNRD2. In addition, we identified C10orf58, an uncharacterized protein structurally similar to the thioredoxins, which could represent a hitherto unknown component of antioxidant defense.

Our large-scale computational analysis uncovered strong co-expression between heme biosynthesis and the Fe-S cluster assembly proteins ISCA1, ISCA2 and C1orf69. A functional link between these two processes was recently discovered in zebrafish erythrocytes, where defects in the Fe-S cluster assembly protein GLRX5 disrupts heme synthesis by inhibiting translation of ALAS2 in erythrocytes through IRP1 (Wingert et al., 2005). This regulatory mechanism is thought to act as a cellular iron sensor that prevents synthesis of the toxic porphyrins when iron is scarce. However, there are other plausible reasons for synchronizing Fe-S cluster assembly with heme synthesis. For example, both heme and Fe-S clusters serve as co-factors in electron-transferring proteins such as those in the respiratory chain. An Fe-S cluster is also required by mammalian ferrochelatase, which catalyzes the final step of heme synthesis. Moreover, the three Fe-S cluster synthesis proteins identified in our screen (ISCA1, ISCA2 and C1orf69) appear to specialize in assembling Fe-S clusters on a subset of mitochondrial enzymes, including the citric acid cycle enzyme aconitase, and lipoic acid synthetase, which produces an essential cofactor for the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (Gelling et al., 2008; Lill and Mühlenhoff, 2008). Impaired assembly of Fe-S clusters on these enzymes could hamper the production of succinyl-CoA, which is required in vast amounts for erythroid heme synthesis (Figure 1A; Shemin et al., 1955). Further investigation is needed to determine which of these, or other, hypotheses are correct.

At the outset, one of this study’s goals was to identify transporters responsible for trafficking heme precursors between the mitochondrial and cytosolic compartments. Expression screening implicated a handful of mitochondrial proteins with transmembrane domains that might be candidates for such transporters. One of these is the mitochondrial solute carrier SLC22A4. This gene is highly homologous to the carnitine transporter SLC22A5 (OCTN2), but has low affinity for carnitine and does not rescue carnitine deficiency in mice (Zhu et al., 2000). SLC22A4 has been suggested to protect red blood cells from oxidative stress (Grundemann et al., 2005), and a previous study found that terminal differentiation of MEL cells is disrupted upon SLC22A4 depletion, although the cause of this is unclear (Nakamura et al., 2007). The protein is present in both the mitochondrial and plasma membranes (Lamhonwah and Tein, 2006). We also identified TMEM14C, a short mitochondrial transmembrane protein (112 amino acids) of which nothing was known prior to this study. This gene is found only in vertebrate animals; it exhibits strong expression in zebrafish ICM and appears essential for functional heme biosynthesis in erythrocytes, making this a strong candidate for further studies. An additional high-scoring gene is MCART1, also a mitochondrial solute carrier. Its role in erythrocyte biology remains to be established.

In the current study we chose to focus our efforts on the solute carrier SLC25A39. This gene localizes to the mitochondrial membrane (Luk et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2001), and we demonstrate that it is the functional vertebrate ortholog of yeast MTM1. MTM1 was previously described as a manganese transporter (Luk et al., 2003), but mtm1Δ mutants do not show altered mitochondrial manganese levels, and more recent data suggests that its primary role is in mitochondrial iron homeostasis (Luk et al., 2003). Deletion of MTM1 causes mitochondrial iron overload (Yang et al., 2006) and up-regulation of the Fe-S scaffold proteins Isu1 and Isu2 (A.N. and V.C.C., unpublished data), phenotypes that we found to be complemented by vertebrate SLC25A39. We here show that slc25a39 is required for heme synthesis in zebrafish. Furthermore, our data in MEL cells demonstrate that mouse Slc25a39 is not an iron transporter, since mitochondrial iron levels were unaffected when Slc25a39 expression was silenced by siRNA. However, silencing of Slc25a39 did affect iron incorporation into heme to an extent similar to that of Slc25a37, the principal mitochondrial iron importer in erythroid cells (Shaw et al., 2006a).

Based on our data in MEL cells, silencing SLC25A39 either impairs incorporation of iron into PPIX by ferrochelatase, or inhibits PPIX synthesis altogether; however, morpholino knockdown of slc25a39 in zebrafish did not result in a porphyric phenotype, arguing against a direct participation of SLC25A39 in the terminal steps of protoporphyrin synthesis. Thus, our data suggest a role for SLC25A39 either in early heme synthesis or in its regulation via ALA synthase. In vertebrate erythrocytes, availability of Fe-S clusters regulates ALAS2 through IRP1, demonstrated by recent work focusing on the zebrafish mutant shiraz (Wingert et al., 2005). This mutant harbored mutations in the Fe-S cluster enzyme grx5 which abolished heme biosynthesis. Interestingly, the observed phenotypic consequences of defects in GLRX5 and SLC25A39 are strikingly similar in both yeast and vertebrates: in zebrafish, neither defects in slc25a39 nor in grx5 result in porphyria (Figure 5; Wingert et al., 2005), and yeast mtm1Δ or grx5Δ cells both accumulate mitochondrial iron (Yang et al., 2006) and exhibit a marked increase in the Fe-S scaffold proteins Isu1/Isu2 (Figure 6; Bellí et al., 2004). In general, defects in Fe-S cluster assembly in yeast result in mitochondrial iron overload, while heme deficiency due to dysfunctional ALA synthase does not (Crisp et al., 2003). Based on our and previously published observations, we hypothesize that vertebrate SLC25A39 may be involved in Fe-S cluster synthesis, and that the observed effects on heme synthesis (Figure 4B and Figure 5F) might be mediated through IRP1, analogous to what has been described for GLRX5 (Wingert et al., 2005), though future experiments will be required to critically test this hypothesis.

In summary, this study demonstrates that large-scale integration of gene expression data has the potential to identify additional components of partially known, transcriptionally regulated pathways with high precision. Our computational analysis and follow-up studies have identified and confirmed roles for five mitochondrial proteins in heme biosynthesis, revealed tightly coordinated expression of the iron sulfur cluster assembly and heme biosynthesis pathways in maturing erythrocytes, and specifically predicted a primary function for SLC25A39 in Fe-S cluster assembly, which is required to maintain functional heme biosynthesis in developing erythrocytes. While the precise molecular function of this and other proteins identified herein remain to be addressed in full, our findings open up new avenues of research into erythrocyte biology and provide candidate genes for human hematological disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Data sets

All microarray data sets for five Affymetrix platforms (human U133A, U133+; mouse U74Av2, M430 and M430A) containing at least 6 arrays were downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (Barrett et al., 2007) during March 2008. Overlapping data sets were merged, resulting in 1,426 distinct data sets. We used the signal-level data provided in GEO matrix files. Signal values were un-logged if necessary and normalized separately for each data set by scaling each array to its 2% trimmed mean. To establish a unique identifier per gene across species and platforms, we first mapped Affymetrix probesets to NCBI Gene IDs as previously described (Dai et al., 2005), and then mapped these to NCBI Homologene identifiers (Sayers et al., 2009). The set of 1,097 genes encoding mitochondrial proteins was defined as previously described (Pagliarini et al., 2008) and mapped to Homologene identifiers, resulting in 1,032 genes with homology between human and mouse.

Expression screening

Briefly, expression screening was performed as follows; the full details of the computational algorithm is described elsewhere (J.B., R.N., V.K.M, unpublished). We first treated each of the five microarray platforms separately. Affymetrix probesets for the eight heme biosynthesis enzymes were chosen manually by sequence matching to RefSeq transcript models. To avoid confounding the differently regulated liver and erythrocyte heme synthesis pathways, we included only the erythrocyte-specific form ALAS2 for ALA synthase. For each data set, we calculated the GSEA-P enrichment score (Subramanian et al., 2005) between the heme biosynthesis probesets (the query pathway) and all other probesets matching the mitochondrial genes, using the Pearson correlation coefficient as the base measure. We repeated this procedure with arrays randomly permuted 100,000 times to generate a null distribution of enrichment scores. Global false discovery rate (FDR) estimation was then performed as previously described (Efron, 2007; Subramanian et al., 2005), and the coexpression probability qgd (Figure 1A) was defined as 1 – FDR of probeset g in data set d. Data sets weights wd were defined as the average of qgd with g ranging over the heme biosynthesis probesets. For each probeset, we integrated the false discovery rates from all data sets using a robust Bayesian meta-analysis method (Genest and Schervish, 1985) to obtain the final probability pg. Finally, we selected the best-scoring probeset for each Homologene identifier and repeated this procedure across all platforms to obtain a unique pg for each gene g with homology between mouse and human.

cDNA clones

The cDNA clones from mouse and zebrafish for the candidate genes were obtained from Open Biosystems. The zebrafish cDNA clone for slc22a5 was isolated by RT-PCR using primers based on the sequence in the GenBank database (XM_001340800) and total RNA from wild type embryos at 19hpf.

Zebrafish animal husbandry

Standard AB and cloche (clom39) strains were used in our studies and were raised in compliance with IACUC regulations.

Zebrafish in situ hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled probe synthesis and whole mount in situ hybridization was performed as described (Shaw et al., 2006a). For expression analysis of slc22a4, slc22a5, slc25a39, c1orf69, isca1, tmem14c and slc4a1, 24hpf embryos from matings between heterozygous cloche zebrafish were used. Myeloperoxidase and αE3-globin (hbae3) expression was determined in morpholino injected AB wildtype embryos fixed at 24- and 48hpf.

Morpholino Injections

Splice junction targeting morpholinos were ordered from Gene Tools (for sequences see Supplementary Table S2). AB wildtype embryos were injected at the one-cell stage and stained with o-dianisidine at 48hpf as described (Shaw et al., 2006a). The injected morpholino concentrations ranged from 0.4 to 0.9mM. The ferrochelatase specific morpholino was as described (Wingert et al., 2005). Zebrafish pictures were taken with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E microscope, and using MetaMorph software.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR

Thirty control AB wildtype and morpholino injected embryos were collected at 24hpf and RNA was isolated using TriZol Reagent (Invitrogen) and genomic DNA Eliminator columns (Qiagen). RNA integrity was assessed on a 2% agarose gel and yield was determined on a Spectrophotometer (Beckman). The First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) was used to generate cDNA from one microgram total RNA. Primer sequences for the detection of aberrantly splice mRNA species are in Supplementary Table S3. Real-time PCR was performed on an iQ5 Real-Time PCR Detection System (BIO-RAD). TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and normalized gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

Mouse Tissue Northern Blots

The multiple tissue northern blot was obtained from Seegene. Ten micrograms of total RNA from mouse adult bone marrow and fetal liver were subjected to northern analysis. The nylon blots were serially hybridized with 32P-labeled mouse Slc25a39 and GAPDH probes using standard procedures.

Mouse in situ Hybridization

Non-radioactive in situ hybridization was performed using antisense digoxigenin-UTP-labeled RNA probes (Roche). Procedures were essentially as described (Palis and Kingsley, 1995). In brief, five micron sections from paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin embedded outbred mouse embryos were hybridized overnight at 52°C after proteinase K and acetic anhydride pretreatment. Posthybridization washes included RNase treatment. Alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibodies were developed using BM purple BCIP/NBT substrate (Roche).

siRNA knockdown

siRNA oligos to Slc25A39, Slc25A37, and control oligos were purchased from Dharmacon. A myc-tagged cDNA for mouse Slc25A39 was constructed in pCMV-Tag5 vector (Stratagene) and co-transfected into MEL cells using the Amaxa nucleofection reagent and device. Western analysis with anti-myc and anti-tubulin antibodies was performed using standard procedures. siRNA procedures in differentiating MEL cells and preparation of 59Fe saturated transferrin were performed as described (Paradkar et al., 2008).

Yeast complementation analysis

The WT strain BY4741 and the isogenic MY019 (mtm1Δ) were as described (Yang et al., 2006). Strains were transformed by the lithium acetate procedure with URA3 2µ based vectors that either expressed MTM1 from its native promoter (pLJ063) (Luk et al., 2003) or zebrafish slc25a39 and mouse Slc25A39. As needed, these transformants were induced to subsequently shed the URA3-based vectors by growth on medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) (Boeke et al., 1987). Cells were grown without shaking for 18–20 hours to a final OD600 to mid-log phase in SD (synthetic dextrose) medium (Sherman et al., 1978). The whole cell lysates prepared by glass bead homogenization were analyzed for SOD activity by native gel electrophoresis and nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining, and for immunoblot analysis of yeast Sod2p (Luk et al., 2003), Pgk1p (Jensen et al., 2004) and total Isu1p and Isu2p using an anti-E. coli IscU antibody kindly provided by L. Vickery (Garland et al., 1999). To test for complementation of the mtm1Δ loss of mitochondrial DNA, WT cells transformed with either pRS426-ADH empty vector or with zSLC25A39 were subjected to a MTM1 gene deletion using the mtm1::LEU2 plasmid pVC257 (Luk et al., 2003). The resultant mtm1::LEU2 derivatives were then tested for growth on enriched yeast extract peptone based medium containing either fermentable (2% glucose) or non-fermentable (3% glycerol) carbon sources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Christian Lawrence, Jason Best and others for the zebrafish animal husbandry, Babette Gwynn and Luanne Peters for providing mouse fetal liver RNA and adult bone marrow cells, and Joe Italiano for access to the CCD camera and MetaMorph software. We thank members of our labs for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Knut & Alice Wallenberg Foundation (R.N.); the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research/NOW (I.J.S.); the March of Dimes Foundation (B.H.P.); American Diabetes Association/Smith Family Foundation (V.K.M.); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (V.K.M.); the JHU NIEHS center (V.C.C); the American Society of Hematology (K.A.S.); and the NIH (P.D.K., V.C.C. R01ES08996, J.K. R01DK052380, J.P., B.H.P. R01DK070838 & P01HL032262, V.K.M. R01GM077465).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

GenBank Accession numbers: Zebrafish clones for slc25a39 (NM_200486), slc22a5 (XM_001340800), slc22a4 (NM_200849), isca1 (NM_001025178), c1orf69 (NM_001076635), and tmem14c (NM_001045438); mouse clones for Slc25a39 (NM_026542), Slc22a4 (NM_019687), Isca1 (NM_026921), C1orf69 (NM_173785), and Tmem14c (NM_025387).

Author Information: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- Ajioka RS, Phillips JD, Kushner JP. Biosynthesis of heme in mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:723–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R, Raskind WH, Hutchinson A, Schueck ND, Dean M, Koeller DM. Mutation of a putative mitochondrial iron transporter gene (ABC7) in X-linked sideroblastic anemia and ataxia (XLSA/A) Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:743–749. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Rudnev D, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Soboleva A, Tomashevsky M, Edgar R. NCBI GEO: mining tens of millions of expression profiles--database and tools update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D760–D765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CM, Kanki JP, Rhodes J, Liu TX, Paw BH, Kieran MW, Langenau DM, Delahaye-Brown A, Zon LI, Fleming MD, et al. Myelopoiesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Blood. 2001;98:643–651. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke JD, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink GR. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:164–175. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahan P, Rovegno F, Mooney D, Newman JC, St Laurent G, 3rd, McCaffrey TA. Meta-analysis of microarray results: challenges, opportunities, and recommendations for standardization. Gene. 2007;401:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camaschella C, Campanella A, De Falco L, Boschetto L, Merlini R, Silvestri L, Levi S, Iolascon A. The human counterpart of zebrafish shiraz shows sideroblastic-like microcytic anemia and iron overload. Blood. 2007;110:1353–1358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman SS, Meyron-Holtz EG, Olivierre-Wilson H, Ghosh MC, McConnell JP, Rouault TA. Microcytic anemia, erythropoietic protoporphyria, and neurodegeneration in mice with targeted deletion of iron-regulatory protein 2. Blood. 2005;106:1084–1091. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter PD, Baumann M, Bishop DF. Enzymatic defect in "X-linked" sideroblastic anemia: molecular evidence for erythroid delta-aminolevulinate synthase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4028–4032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp RJ, Pollington A, Galea C, Jaron S, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Kaplan J. Inhibition of heme biosynthesis prevents transcription of iron uptake genes in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45499–45506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Wang P, Boyd AD, Kostov G, Athey B, Jones EG, Bunney WE, Myers RM, Speed TP, Akil H, et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwan A, Koesters AG, Odley AM, Pushkaran S, Baines CP, Spike BT, Daria D, Jegga AG, Geiger H, Aronow BJ, et al. Unrestrained erythroblast development in Nix−/− mice reveals a mechanism for apoptotic modulation of erythropoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6794–6799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610666104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Size, power and false discovery rates. Annals of Statistics. 2007;35:1351–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Garland SA, Hoff K, Vickery LE, Culotta VC. Saccharomyces cerevisiae ISU1 and ISU2: members of a well-conserved gene family for iron-sulfur cluster assembly. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:897–907. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelling C, Dawes IW, Richhardt N, Lill R, Mühlenhoff U. Mitochondrial Iba57p is required for Fe/S cluster formation on aconitase and activation of radical SAM enzymes. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1851–1861. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01963-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genest C, Schervish MJ. Modeling expert judgements for Bayesian updating. The Annals of Statistics. 1985;13:1198–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Grundemann D, Harlfinger S, Golz S, Geerts A, Lazar A, Berkels R, Jung N, Rubbert A, Schomig E. Discovery of the ergothioneine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5256–5261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408624102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guernsey DL, Jiang H, Campagna DR, Evans SC, Ferguson M, Kellogg MD, Lachance M, Matsuoka M, Nightingale M, Rideout A, et al. Mutations in mitochondrial carrier family gene SLC25A38 cause nonsyndromic autosomal recessive congenital sideroblastic anemia. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.359. Epub ahead of print, May 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LT, Sanchez RJ, Srinivasan C, Valentine JS, Culotta VC. Mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae iron-sulfur cluster assembly genes and oxidative stress relevant to Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29938–29943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DC, Dean DR, Smith AD, Johnson MK. Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:247–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MA, Addya S, Vadigepalli R, Banini B, Delgrosso K, Huang H, Surrey S. Transcriptional regulatory network analysis of developing human erythroid progenitors reveals patterns of coregulation and potential transcriptional regulators. Physiol Genomics. 2006;28:114–128. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00055.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy PC, Du G, Fukuda Y, Sun D, Sampath J, Mercer KE, Wang J, Sosa-Pineda B, Murti KG, Schuetz JD. Identification of a mammalian mitochondrial porphyrin transporter. Nature. 2006;443:586–589. doi: 10.1038/nature05125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamhonwah AM, Tein I. Novel localization of OCTN1, an organic cation/carnitine transporter, to mammalian mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1315–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange H, Mühlenhoff U, Denzel M, Kispal G, Lill R. The heme synthesis defect of mutants impaired in mitochondrial iron-sulfur protein biogenesis is caused by reversible inhibition of ferrochelatase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29101–29108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill R, Mühlenhoff U. Maturation of iron-sulfur proteins in eukaryotes: mechanisms, connected processes, and diseases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:669–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.162653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low FM, Hampton MB, Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Peroxiredoxin 2 functions as a noncatalytic scavenger of low-level hydrogen peroxide in the erythrocyte. Blood. 2007;109:2611–2617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-048728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk E, Carroll M, Baker M, Culotta VC. Manganese activation of superoxide dismutase 2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires MTM1, a member of the mitochondrial carrier family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10353–10357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1632471100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May BK, Dogra SC, Sadlon TJ, Bhasker CR, Cox TC, Bottomley SS. Molecular regulation of heme biosynthesis in higher vertebrates. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;51:1–51. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60875-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Hentze MW. Systemic iron homeostasis and the iron-responsive element/iron-regulatory protein (IRE/IRP) regulatory network. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:197–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Sugiura S, Kobayashi D, Yoshida K, Yabuuchi H, Aizawa S, Maeda T, Tamai I. Decreased proliferation and erythroid differentiation of K562 cells by siRNA-induced depression of OCTN1 (SLC22A4) transporter gene. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1628–1635. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini DJ, Calvo SE, Chang B, Sheth SA, Vafai SB, Ong SE, Walford GA, Sugiana C, Boneh A, Chen WK, et al. A mitochondrial protein compendium elucidates complex I disease biology. Cell. 2008;134:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palis J, Kingsley PD. Differential gene expression during early murine yolk sac development. Mol Reprod Dev. 1995;42:19–27. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080420104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradkar PN, Zumbrennen KB, Paw BH, Ward DM, Kaplan J. Regulation of mitochondrial iron import through differential turnover of mitoferrin1 and mitoferrin2. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01685-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paw BH, Davidson AJ, Zhou Y, Li R, Pratt SJ, Lee C, Trede NS, Brownlie A, Donovan A, Liao EC, et al. Cell-specific mitotic defect and dyserythropoiesis associated with erythroid band 3 deficiency. Nat Genet. 2003;34:59–64. doi: 10.1038/ng1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondarre C, Campagna DR, Antiochos B, Sikorski L, Mulhern H, Fleming MD. Abcb7, the gene responsible for X-linked sideroblastic anemia with ataxia, is essential for hematopoiesis. Blood. 2007;109:3567–3569. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponka P. Tissue-specific regulation of iron metabolism and heme synthesis: distinct control mechanisms in erythroid cells. Blood. 1997;89:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quackenbush J. Computational analysis of microarray data. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:418–427. doi: 10.1038/35076576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouault TA. The role of iron regulatory proteins in mammalian iron homeostasis and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:406–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval H, Thiagarajan P, Dasgupta SK, Schumacher A, Prchal JT, Chen M, Wang J. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature. 2008;454:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature07006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa S. Modern diagnosis and management of the porphyrias. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Edgar R, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D5–D15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafizadeh E, Paw BH. Zebrafish as a model of human hematologic disorders. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11:255–261. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000138686.15806.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GC, Cope JJ, Li L, Corson K, Hersey C, Ackermann GE, Gwynn B, Lambert AJ, Wingert RA, Traver D, et al. Mitoferrin is essential for erythroid iron assimilation. Nature. 2006a;440:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature04512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GC, Langer NB, Wang Y, Li L, J K, Bloomer JR, Paw BH. Abnormal Expression of Human Mitoferrin (SLC25A37) Is Associated with a Variant of Erythropoietic Protoporphyria. Blood. 2006b;103(11):6A. (abstract 3) [Google Scholar]

- Shemin D, Russell CS, Abramsky T. The succinate-glycine cycle. I. The mechanism of pyrrole synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1955;215:613–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F, Fink GR, Lawrence CW. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Shirihai OS, Gregory T, Yu C, Orkin SH, Weiss MJ. ABC-me: a novel mitochondrial transporter induced by GATA-1 during erythroid differentiation. Embo J. 2000;19:2492–2502. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spike BT, Dibling BC, Macleod KF. Hypoxic stress underlies defects in erythroblast islands in the Rb-null mouse. Blood. 2007;110:2173–2181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerton J, Weller D. Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation, and properties. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:187–195. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whatley SD, Ducamp S, Gouya L, Grandchamp B, Beaumont C, Badminton MN, Elder GH, Holme SA, Anstey AV, Parker M, et al. C-terminal deletions in the ALAS2 gene lead to gain of function and cause X-linked dominant protoporphyria without anemia or iron overload. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingert RA, Galloway JL, Barut B, Foott H, Fraenkel P, Axe JL, Weber GJ, Dooley K, Davidson AJ, Schmid B, et al. Deficiency of glutaredoxin 5 reveals Fe-S clusters are required for vertebrate haem synthesis. Nature. 2005;436:1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/nature03887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Cobine PA, Molik S, Naranuntarat A, Lill R, Winge DR, Culotta VC. The effects of mitochondrial iron homeostasis on cofactor specificity of superoxide dismutase 2. Embo J. 2006;25:1775–1783. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XX, Lewin DA, Zhong A, Brush J, Schow PW, Sherwood SW, Pan G, Adams SH. Overexpression of the human 2-oxoglutarate carrier lowers mitochondrial membrane potential in HEK-293 cells: contrast with the unique cold-induced mitochondrial carrier CGI-69. Biochem J. 2001;353:369–375. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Jong MC, Frazer KA, Gong E, Krauss RM, Cheng JF, Boffelli D, Rubin EM. Genomic interval engineering of mice identifies a novel modulator of triglyceride production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1137–1142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.