Abstract

Dietary restriction extends the lifespan of numerous, evolutionarily diverse species1. In D. melanogaster, a prominent model for research on the interaction between nutrition and longevity, dietary restriction is typically based on medium dilution, with possible compensatory ingestion commonly being neglected. Possible problems with this approach are revealed by using a method for direct monitoring of D. melanogaster feeding behavior. This demonstrates that dietary restriction elicits robust compensatory changes in food consumption. As a result, the effect of medium dilution is overestimated and, in certain cases, even fully compensated for. Our results strongly indicate that feeding behavior and nutritional composition act concertedly to determine fly lifespan. Feeding behavior thus emerges as a central element in D. melanogaster aging.

Defined as a reduction in nutrient intake without malnutrition, dietary restriction prolongs the life of species as diverse as nematodes, insects and mammals1,2, with preliminary results indicating that this effect may be conserved in primates as well3,4. In rodents (where it is commonly known as caloric restriction), dietary restriction also prolongs vitality and delays the onset of age-associated diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular pathology5,6. Animals subjected to chronic dietary restriction exhibit multiple physiological changes, including reduced glucose, insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) blood levels, increased insulin sensitivity and overall dampened inflammatory response6. In addition, studies in human subjects suggest that dietary restriction may positively impact critical health factors such as blood pressure and glucose and cholesterol blood levels7–9. Despite the obvious biomedical relevance of research on dietary restriction, seven decades of work have conveyed little mechanistic insight. In particular, and as a result of the wide variety of methods used for dietary restriction application in different model organisms, it remains unclear whether the evolutionarily conserved beneficial effect is exerted through a common physiological mechanism.

In both nematodes and rodents, dietary restriction heavily relies on patterns of feeding behavior. In Caenorhabditis elegans, where pharyngeal pumping rate serves as an indirect measure of food intake10,11, the most common method of dietary manipulation takes advantage of animals defective in pharyngeal constriction — the eat mutants12. The food source, the bacterium Escherichia coli, is provided in abundance, but ingestion is limited by the neuromuscular defect of the mutants. In experiments with rodents, the ‘restricted’ group is fed a fraction (typically ∼65%) of the food consumed by the ad libitum group2. Therefore, in both of these model systems dietary restriction relies on a bona fide reduction of nutrient intake. In contrast, dietary restriction in D. melanogaster typically involves simple dilution of the food medium13,14. This procedure, as a rule, is not accompanied by direct quantitation of intake, neglecting potential changes in ingestion leading to partial or total nutritional compensation. Compensatory feeding in response to changes in food composition has been described in several insect species15,16. In D. melanogaster, however, partly owing to differences in methodology, no consensus has been reached regarding this issue, and the general assumption underlying dietary restriction studies is that compensation is negligible or does not occur. Previous work suggests that fruit flies can sense sucrose concentration and accordingly regulate intake17,18, but the conditions used in these studies differ markedly from the customary laboratory media used for raising and aging flies. Indirect measures, such as fecal pellet density, also indicate that nutrient dilution can produce compensatory feeding19. In contrast, a recent report asserts that dietary manipulation elicits essentially no compensatory ingestion, based on the fraction of animals with their proboscis contacting the food at a given time, but without any measurement of actual intake20.

D. melanogaster is a particularly valuable model for the study of the interaction between nutrition and mortality, having yielded some of the most important recent advances in our understanding of the effects of dietary manipulation. It is essential that the methodology of dietary restriction application be consistently established if the mechanisms of lifespan extension by nutrient modulation are to be elucidated in this model system. By using a method to directly monitor D. melanogaster feeding behavior, we demonstrate that dietary restriction elicits dramatic changes in the volume of food ingestion that can compensate for differences in medium concentration, making the latter a misleading value when considered in isolation. In addition, our findings indicate that the lifespan of D. melanogaster is not exclusively determined by food source composition, but rather it is the product of the interaction between nutrient availability and active feeding behavior.

Dietary restriction elicits dramatic compensatory feeding behavior

Isotope labeling of the food medium allows for sensitive and specific quantitation of intake. We determined adult feeding rate in four dietary regimes over 24 h by incorporating a [α-32P]dCTP tracer in the fly food. Signal incorporation was near-linear up to 72 h (data not shown). The four media were based on a binder of 8% cornmeal, 0.5% bacto agar and 1% propionic acid, with added sucrose and yeast extract at defined concentrations. We defined 1× as 1% sucrose + 1% yeast extract (see Supplementary Methods online). Nutrient dilution had a striking impact on volume of food intake (Fig. 1). Flies maintained on 5×, 10× and 15× regimes ingested, respectively, 2.6, 3.8 and 5.4 times less volume than animals on 1×. We obtained identical results with three alternative tracers: [14C]leucine, [14C]sucrose and [α-32P]dATP (data not shown). Both the absolute values and the ratios between differently-fed groups were remarkably reproducible, both within (Fig. 1a) and across experiments, indicating that appetite is surprisingly constant under each set of dietary conditions and tightly regulated in response to food changes. Notably, our measurements of isotope incorporation reflect nutrient assimilation rather than simple ingestion and may thus be the most pertinent value to studies of metabolism and physiology.

Figure 1.

Regulation of feeding behavior in response to dietary modulation. (a) Volume of food ingested per fly over 24 h on four different medium concentrations at 25 °C (mean ± s.d. of four replicate samples of 15 females each). Unpaired, two-tailed t tests: 1× versus 5×, P = 0.0001; 5× versus 10×, P = 0.0005; 10× versus 15×, P = 0.0003 (b) Net sucrose and yeast extract intake on the four nutritional conditions, in micrograms ingested per fly per 24 h (mean ± s.d.). Inset, actual nutrient intake (solid line) markedly differs from expected intake based on medium concentration only (dashed line).

We determined the amount of sucrose plus yeast extract ingested over 24 h (Fig. 1b). The result markedly contrasts with expected values based on nutrient concentration alone (Fig. 1b, inset). For instance, enriching the medium from 1× to 5× resulted in less than a twofold increase in nutrient uptake, and flies on 10× consumed only 33% more nutrients than animals on 5×. Most strikingly, raising food concentration from 10× to 15× did not alter actual nutrient intake. It is also worth noting that, between 5× and 15×, regimes similar to the ones commonly referred to, respectively, as “dietary restriction” and “control”20, and generally assumed to represent a 200% enrichment, the observed actual difference in nutrient intake was only 40%. These results demonstrate the existence of a behavioral mechanism allowing D. melanogaster to actively compensate for differences in food source composition, and call for a reassessment of the protocols used for dietary manipulation in this species.

Feeding behavior influences lifespan

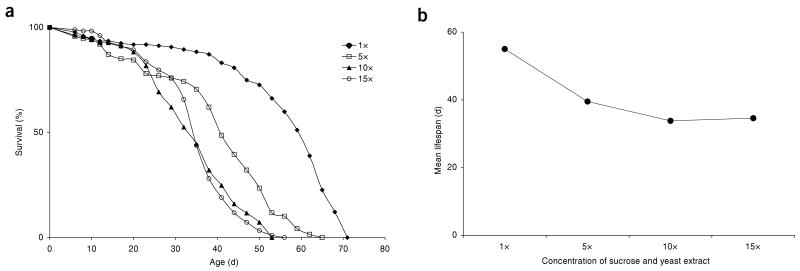

We hypothesized that feeding behavior is a central determinant of longevity. We therefore expected the lifespan of flies aged on the different regimes to parallel nutrient ingestion rate, rather than the composition of the medium alone. In fact, survival on 10× and 15× food did not differ significantly (P = 0.8; Fig. 2). This is in full agreement with our measurements of actual nutrient intake (Fig. 1b) and clearly contradicts the expectation based on medium dilution (Fig. 1b, inset). Moreover, as illustrated by the symmetry of the two curves in Figures 1b and 2b, mean lifespan correlated tightly with nutrient intake, but not with food concentration (Fig. 1b, inset). Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that actual nutrient intake is a central determinant of lifespan in flies subjected to dietary manipulation, whereas medium dilution, considered in isolation, is not a reliable parameter.

Figure 2.

Feeding behavior influences D. melanogaster lifespan. (a) Survival for virgin females at 25 °C on four different nutritional concentrations. Longevity correlates with actual food intake. (b) Mean lifespan as a function of medium concentration. Survival on 5× is 28% shorter than on 1× (logrank test, P < 0.0001, χ2 = 134.8), and 17% longer than on 10× (logrank test, P < 0.0001, χ2 = 30.72), whereas lifespan on 10× and 15× does not differ significantly (logrank test, P = 0.7993, χ2 = 0.06466). 1×, n = 172, mean = 55 d; 5×, n = 187, mean = 40 d; 10×, n = 137, mean = 34 d; 15×, n = 178, mean = 35 d.

Conclusion

Our findings draw attention to the importance of monitoring a behavioral element in D. melanogaster longevity studies, particularly those involving dietary manipulation. Much like lifespan, any biological process depending heavily on nutrition is likely to be the result of a fine balance between two elements, one passive—food composition—and one active—feeding behavior. Other fields in which nutrition is an essential factor (for example, growth, reproduction and obesity) should therefore equally benefit from careful characterization of the role of fly appetite. Although feeding rates are likely to vary under different laboratory conditions, the magnitude and reproducibility of the effect described here strongly suggests a conserved phenomenon. It will be of particular interest to determine the conditions under which appetite compensation is partial or complete. Further work will also be required to determine the role of individual food components in appetite regulation.

Adaptation of feeding behavior to nutrient source composition has an important ecological role in the wild. In the presence of plentiful and highly nutritious food, it is of evident advantage to limit intake. Conversely, when nutrient sources are poor or scarce, flies will benefit from ingesting larger meals. Elucidation of the physiological and molecular bases of appetite modulation in D. melanogaster may bear relevance to understanding such pathologies as obesity and feeding disorders.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Methods website.

Competing Interests Statement: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Guarente L, Kenyon C. Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nature. 2000;408:255–262. doi: 10.1038/35041700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guarente L, Picard F. Calorie restriction—the SIR2 connection. Cell. 2005;120:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane MA, Mattison J, Ingram DK, Roth GS. Caloric restriction and aging in primates: Relevance to humans and possible CR mimetics. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:335–338. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth GS, Ingram DK, Lane MA. Caloric restriction in primates and relevance to humans. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;928:305–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weindruch R, Walford RL. The Retardation of Aging and Disease by Dietary Restriction. C.C. Thomas; Springfield, Illinois: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longo VD, Finch CE. Evolutionary medicine: from dwarf model systems to healthy centenarians? Science. 2003;299:1342–1346. doi: 10.1126/science.1077991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walford RL, Harris SB, Gunion MW. The calorically restricted low-fat nutrient-dense diet in Biosphere 2 significantly lowers blood glucose, total leukocyte count, cholesterol, and blood pressure in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11533–11537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walford RL, Mock D, Verdery R, MacCallum T. Calorie restriction in Biosphere 2: alterations in physiologic, hematologic, hormonal, and biochemical parameters in humans restricted for a 2-year period. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:B211–B224. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.6.b211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heilbronn LK, Ravussin E. Calorie restriction and aging: review of the literature and implications for studies in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:361–369. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klass MR. A method for the isolation of longevity mutants in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and initial results. Mech Ageing Dev. 1983;22:279–286. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(83)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apfeld J, Kenyon C. Regulation of lifespan by sensory perception in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;402:804–809. doi: 10.1038/45544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakowski B, Hekimi S. The genetics of caloric restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13091–13096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman T, Partridge L. Female fitness in Drosophila melanogaster: an interaction between the effect of nutrition and of encounter rate with males. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1996;22:755–759. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogina B, Helfand SL, Frankel S. Longevity regulation by Drosophila Rpd3 deacetylase and caloric restriction. Science. 2002;298:1745. doi: 10.1126/science.1078986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelperin A, Dethier VG. Long-term regulation of sugar intake by blowfly. Physiol Zool. 1967;40:218. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson SJ, et al. The patterning of compensatory sugar feeding in the australian sheep blowfly. Physiol Ent. 1989;14:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edgecomb RS, Harth CE, Schneiderman AM. Regulation of feeding behavior in adult Drosophila melanogaster varies with feeding regime and nutritional state. J Exp Biol. 1994;197:215–235. doi: 10.1242/jeb.197.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson ED, Reeder BA, Bruce RD. Characterization of a method for quantitating food consumption for mutation assays in Drosophila. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1991;18:14–21. doi: 10.1002/em.2850180104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Driver CJ, Wallis R, Cosopodiotis G, Ettershank G. Is a fat metabolite the major diet dependent accelerator of aging? Exp Gerontol. 1986;21:497–507. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(86)90002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mair W, Piper MD, Partridge L. Calories do not explain extension of life span by dietary restriction in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.